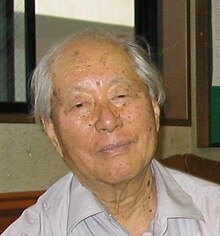

Takeo Kimura

Takeo Kimura | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | April 1, 1918 Tokyo, Japan |

| Died | March 21, 2010 (aged 91) Tokyo, Japan |

| Occupation(s) | Art director, writer, film director |

Takeo Kimura (木村 威夫, Kimura Takeo, April 1, 1918 – March 21, 2010) was a Japanese art director, writer and film director. Beginning his career in 1945 he art-directed well over 200 films. He was one of Japan's best known art directors, most famously for his collaborations with cult director Seijun Suzuki through the 1960s at the Nikkatsu Company, exemplified by Tokyo Drifter (1966). Other directors with whom he frequently worked include Toshio Masuda, Kazuo Kuroki, Kei Kumai and Kaizo Hayashi. At age 90 he made his feature film directorial debut with Dreaming Awake (2008). He had also worked as a critic, writer, painter, photographer and teacher.

Career

[edit]Kimura was born in Tokyo on April 1, 1918. A graduate of Aoyama Gakuin University with a background in theatre, Kimura joined the Nikkatsu Company's scenography department in 1941.[1] The same year, the government ordered the ten major movie studios to consolidate into two. A counteroffer of three was accepted and Nikkatsu merged with Daito and Shinko, the first shutting down their film production unit, and the new company was named Daiei.[2] Kimura continued as an assistant with Daiei after World War II and was promoted to art director in 1945.[1] His debut film was Masanori Igayama's Umi no yobu koe (1945).[3] When Nikkatsu opened a new studio and resumed film production in 1954, Kimura transferred there.[1]

"Kimura is a very unique person, a different kind of art director. He'd suddenly come up with the weirdest idea and just do it. Nikkatsu was very afraid of Kimura and me working together because they thought we might just do something really weird. Kimura makes every movie as if it were his last. And he would think 'if this is my last, then I can do anything I want.' That's why I love working with Kimura as an art director."

At Nikkatsu he worked with many of the studio's directors, including top action director Toshio Masuda,[5] and showed a propensity for realistic set design. However, Kimura became frustrated in doing the same types of films repeatedly and had ambitions to work on films where the art direction was a major focal point.[6] He found an ideal collaborator in the like-minded Seijun Suzuki, a director of primarily B action movies.[7] They first collaborated on The Bastard (1963) which Suzuki considered a turning point in his career.[8] The two became good friends and Kimura became his permanent art director. They worked to refine their style which consisted of more artistry and symbolism than studio bosses generally preferred to see in their action films.[4][7] Among their best known collaborations are Gate of Flesh (1964) and Tokyo Drifter (1966), on which The Japan Times' Mark Schilling wrote, "Who can forget the all-white nightclub in the latter film, with the huge donut-shape, color-shifting mobile – like nothing in real life but expressive of the film's go-go-era, anything-can-happen world."[5] Suzuki considered the art director and cinematographer key collaborators and rewrote the scripts he was assigned over extended discussions with Kimura or cinematographers Katsue Nagatsuka or Shigeyoshi Mine. They would add characters and scenes or expand simple lines into elaborate shots.[9] For his contributions to The Flower and the Angry Waves (1964) Kimura received his first screenwriting credit. He was also included in Hachirō Guryū, the joint pen name for the writing group which formed around Suzuki in the mid-1960s, along with six assistant directors, most prominently Atsushi Yamatoya and Chūsei Sone.[4][9][10]

The Japanese film industry lost much of its viewership to television through the 1960s and, in order to avoid bankruptcy, Nikkatsu shut down regular productions in August 1971, and in November began producing low cost Roman Pornos, romantic softcore pornography films.[11] Kimura left Nikkatsu a couple years later in 1973 to work freelance.[1] He has continued to work steadily outside of the studio system and has since worked with a wide selection of directors including auteur Mitsuo Yanagimachi and multiple collaborations with Kazuo Kuroki and Kaizo Hayashi.[5][12] Stylistically, he continues to vary between the surrealistic, as in his subsequent collaborations with Suzuki, and the realistic, including his films with Kei Kumai.[3] Kimura directed two short films in 2004,[13] and the release of Mugen Sasurai (2004) afforded him the oldest directorial debut at age 86.[3] Following a third and four short film, he directed his first feature-length film at age 90, Dreaming Awake (2008),[12] for which he was recognized by Guinness World Records for "the oldest debut as a feature film director".[14] The film was based on his own novel, which touches on autobiographical elements, and more closely resembles his surrealistic collaborations with Suzuki—who appears in the film as an actor—than his more realistic art direction.[5]

He remained among Japan's best known art directors,[5] most famously for his work with Suzuki through the 1960s.[12] In addition to film, Kimura had worked as a film and art critic, painter, writer, photographer, teacher and on the lecture circuit.[3]

He died of interstitial pneumonia in a Tokyo hospital on March 21, 2010, at the age of 91.[15]

Filmography

[edit]Awards

[edit]Kimura has been nominated for nine Japanese Academy Awards for his art direction and won twice. At the 2nd annual ceremony in 1979, he was nominated for the Outstanding Achievement in a Technical Field for Love and Faith.[16] He won the 1981 award for Outstanding Achievement in Art Direction for An Ocean to Cross, Zigeunerweisen, A Long Way for a Motor Car and The Woman.[17] The following year, he was nomination in the same category for Kei Kumai's Willful Murder,[18] and again in 1983 for the international co-production The Go Masters and Yukko no okurimono: Cosmos no yō ni.[19] At the 12th annual ceremony in 1989, he was co-nominated with Noriyoshi Ikeya for their work on Tokyo: The Last Megalopolis.[20] Kimura received another nomination in 1990 for Kumai's The Death of a Tea Master.[21] His second win came in 1991 for Mt. Aso's Passions, Childhood Days and Hong Kong Paradise.[22] Bandō Tamasaburō's Yearning earned Kimura his last nomination at the 1994 ceremony.[23]

He won three Mainichi Film Awards for Best Art Direction. At the 9th annual ceremony in 1955, he won for A Certain Woman, made at Daiei, and Black Tide, made after he had moved to Nikkatsu.[24] He again won in 1982 for Kumai's Willful Murder.[25] Finally, at the 1987 ceremony he won for The Sea and Poison, House of Wedlock and To Sleep So as to Dream.[26]

Additional awards include Best Artistic Contribution for Mt. Aso's Passions, at the 1990 Montreal World Film Festival,[27] and Best Art Director for The Soul Odyssey, at the 2003 Yokohama Film Festival.[28]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Müller, Marco; Dario Tomasi, eds. (December 1990). Racconti crudeli di gioventù: nuovo cinema giapponese degli anni 60 (in Italian). EDT srl. p. 272. ISBN 978-88-7063-087-9. Archived from the original on July 22, 2011. Retrieved July 31, 2009.

- ^ Richie, Donald (2005). A Hundred Years of Japanese Film: A Concise History, with a Selective Guide to DVDs and Videos. Kodansha International. pp. 96–97. ISBN 4-7700-2995-0. Archived from the original on November 21, 2008.

- ^ a b c d "The Clone Returns Home: Technical Information/Cast/Crew" (DOC). Seattle International Film Festival. Retrieved August 13, 2009. [dead link]

- ^ a b c Puterman, Brian; Robert Graves (1998). "The Seijun Suzuki interview". Asian Cult Cinema. 21. Vital Books: 44–45.

- ^ a b c d e Schilling, Mark (October 2008). "Looking back, one last time". The Japan Times. Retrieved July 21, 2009.

- ^ Suzuki, Seijun; Takeo Kimura; Tadao Sato (Interviewees) (July 2005). Story of a Prostitute: Interviews (DVD). The Criterion Collection.

- ^ a b Weisser, Thomas (1998). "The Films of Seijun Suzuki". Asian Cult Cinema. 21. Vital Books: 51.

- ^ Suzuki, Seijun (1994). "Suzuki on Suzuki". Branded to Thrill: The Delirious Cinema of Suzuki Seijun. Institute of Contemporary Arts. p. 25. ISBN 0-905263-44-8.

- ^ a b Hasumi, Shigehiko (January 1991). "Een wereld zonder seizoenen—A World Without Seasons". De woestijn onder de kersenbloesem—The Desert under the Cherry Blossoms. Uitgeverij Uniepers Abcoude. pp. 7–25. ISBN 90-6825-090-6.

- ^ 木村威夫 (in Japanese). Japanese Movie Database. Retrieved August 6, 2009.

- ^ Schilling, Mark (2007). No Borders, No Limits: Nikkatsu Action Cinema. FAB Press. pp. 20–26. ISBN 978-1-903254-43-1. Archived from the original on October 11, 2008.

- ^ a b c Schilling, Mark (October 2008). "In the director's chair at 90". The Japan Times. Retrieved July 5, 2009.

- ^ 木村威夫 (in Japanese). Allcinema. Retrieved August 13, 2009.

- ^ 木村 威夫学院長 祝 ★ ギネス・ワールド・レコード認定!! (in Japanese). Nikkatsu. Archived from the original on September 27, 2011. Retrieved August 8, 2009.

- ^ "Movie art director Kimura dies at 91". Japan Today. March 25, 2010. Retrieved March 27, 2010.

- ^ 1979年 第 2回 受賞者・受賞作品一覧 (in Japanese). Japan Academy Prize. Archived from the original on January 17, 2008. Retrieved August 6, 2009.

- ^ 1981年 第 4回 受賞者・受賞作品一覧 (in Japanese). Japan Academy Prize. Archived from the original on April 29, 2009. Retrieved August 6, 2009.

- ^ 1982年 第 5回 受賞者・受賞作品一覧 (in Japanese). Japan Academy Prize. Archived from the original on April 29, 2009. Retrieved August 6, 2009.

- ^ 1983年 第 6回 受賞者・受賞作品一覧 (in Japanese). Japan Academy Prize. Archived from the original on April 28, 2009. Retrieved August 6, 2009.

- ^ 1989年 第 12回 受賞者・受賞作品一覧 (in Japanese). Japan Academy Prize. Archived from the original on April 28, 2009. Retrieved August 6, 2009.

- ^ 1990年 第 13回 受賞者・受賞作品一覧 (in Japanese). Japan Academy Prize. Archived from the original on April 28, 2009. Retrieved August 6, 2009.

- ^ 1991年 第 14回 受賞者・受賞作品一覧 (in Japanese). Japan Academy Prize. Archived from the original on April 28, 2009. Retrieved August 6, 2009.

- ^ 1994年 第 17回 受賞者・受賞作品一覧 (in Japanese). Japan Academy Prize. Archived from the original on February 24, 2009. Retrieved August 6, 2009.

- ^ 毎日映画コンクールの歩み: 09 1954年 (in Japanese). Mainichi Film Awards. Retrieved August 7, 2009.

- ^ 毎日映画コンクールの歩み: 36 1981年 (in Japanese). Mainichi Film Awards. Retrieved August 7, 2009.

- ^ 毎日映画コンクールの歩み: 41 1986年 (in Japanese). Mainichi Film Awards. Retrieved August 7, 2009.

- ^ "Les Passions du Mont-Aso". Montreal World Film Festival. Archived from the original on May 27, 2018. Retrieved August 7, 2009.

- ^ 第25回ヨコハマ映画祭 日本映画個人賞 (in Japanese). Yokohama Film Festival. Archived from the original on May 5, 2004. Retrieved August 7, 2009.

External links

[edit]- Takeo Kimura at IMDb

- Takeo Kimura at the Japanese Movie Database (in Japanese)