Electoral reform in New Zealand

|

|---|

|

|

Electoral reform in New Zealand has been a political issue in the past as major changes have been made to both parliamentary and local government electoral systems. A landmark reform was the mixed-member proportional (MMP) system, implemented in 1996 following a public referendum.

National elections in New Zealand were first held in 1853[1] and were conducted over a period of two and a half months. At this time, the country was divided into 24 electorates, who elected one, two or three members (MPs) depending on their population.[2] In the multiple-seat districts, multiple non-transferable vote (block voting) was used; in the single-seat districts the basic first-past-the-post (FPP) was used.

This system continued for a long time, with major diversions being only a change to the second ballot system (a type of two-round system), used for the 1908 election and 1911 election and swiftly repealed in 1913.[3]

In the 1993 electoral reform referendum, New Zealanders voted to adopt the MMP system, a form of proportional representation combining electorate and list MPs, first used in 1996. Proportional representation led to an increase in minor parties entering Parliament, making multi-party governments the norm. Since the introduction of MMP, there have been occasional proposals for further reform; in a 2011 referendum, New Zealanders voted to retain MMP.

Overview

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2025) |

The first-past-the-post voting (FPP) electoral system, used in New Zealand for much of its history, was a simple plurality system, in which voters marked their preference for the candidate they wish to represent the electorate they live in. The candidate or candidates that garners the most votes through this process is then elected to Parliament. Generally, elections conducted in this manner result in an absolute majority,[4] in which the party who wins the most votes wins a majority of seats and has the absolute power in the house. The only deviation from this in New Zealand during the FPP era was before the 1890s during which each member was independent and as such no political parties existed.[5]

A bill was put forward in 1887 to divide the country into two districts, each of 20 members, and to use STV to elect the members. However, it failed to pass.[6]

With the appearance of a New Liberal Party and the Independent Labour League, the old-time two-party system was crumbling significantly. As early as the 1890s, in such ridings as Ashburton the successful candidate had been elected with less than half the votes cast in the district – in 1893 with as few as 32 percent of the vote.

In the 1905 election, for the first time, all members were elected in single-member districts. Concern for fairness and avoidance of the bad effects of vote spitting led NZ to try out a majoritarian system of voting.

The second-ballot system used from 1908 to 1913 was a modification of the existing FPP system. A first election was held same as under FPP, but it guaranteed that a candidate to be elected, must garner over 50% of the votes in their district.[3] If no one reached this threshold in the first count, a new round of voting was conducted featuring only the two highest polling candidates, this ensured one or the other gains over 50%. This was discontinued in 1913, NZ reverting to FPP in single-member districts, the successful candidate winning by plurality, which in many cases was less than half the votes. As well, FPP was producing majority government but not since 1935 has a government been elected by a majority of the votes.

Many NZ voters became dissatisfied with this voting by the 1990s. Mixed-member proportional (MMP), as seen in New Zealand from 1996 onward, is a type of proportional system wherein each voter has two votes. One of these is for the candidate in their electorate and one is for the overall political party.[7] The party vote is what ultimately decides the number of seats each party gains in parliament, with any shortfall between the number of electorates won and the party's overall percentage of the party vote made up by list party members elected.

The impetus to change from FPP to MMP was largely due to the excessive disproportionality FPP elections are prone to. Prominent examples of this include the 1966[8] election, in which the Social Credit Party gained 9% of the vote and yet won only a single seat. Furthermore, this disproportionality often lead to the successful party winning less overall votes than the opposition, but gaining more seats. An example of this is the 1978 election, in which the Labour Party won more than 10,000 votes (0.6%) more than the National Party but gained 11 fewer seats in Parliament.[8]

Another major factor that highlighted the weaknesses of FPP was the potential abuse of power that could occur. New Zealand does not have a written Constitution, and as such it is subject to change. Under FPP the power is concentrated with the leader of the winning party. Prime Minister Robert Muldoon showed this clearly when he illegally abolished the Superannuation scheme upon his election in 1975. Though the Judiciary ruled this move illegal, they were unable to halt the action and Muldoon faced no repercussions for this abuse of power.[9]

Due to these factors, in 1979 the Labour Party adopted policy to seriously consider the adoption of proportional representation in place of the contemporary FPP system. While changes resultant from this were extremely delayed, the undercurrent of support for electoral reform continued and were bolstered by the commissioning of the Royal Commission on the Electoral System in 1985 which ultimately recommended a change to MMP.[10] Finally, both the Labour and National parties entered the 1990 election with policy for a referendum on electoral reform. (The National Party won majority government in the elections of 1990 and 1993 with less than half the votes – evidence of the effects of vote-splitting under FPP, a system not well-suited to the multi-party system that NZ had.)

With both major parties calling for referendum on reform, a referendum to test public sentiment was held in 1992. The 1992 referendum represented the first tangible governmental step towards electoral reform. The results of this referendum overwhelmingly supported change and selected MMP as the preferred electoral system to replace FPP.[11] Due to this a binding referendum was held the following year in 1993, offering a choice between these two systems. MMP was selected by a vote of 53.9% to 46.1%, a majority in favour of change.[12] and was implemented before the next election in 1996.

Parliamentary electoral reform

[edit]Authority for government in New Zealand is derived from Te Tiriti o Waitangi (Treaty of Waitangi),[13] which was signed in 1840. The meaning of Te Tiriti is complicated by the fact that the Maori and English texts of the agreement are not entirely consistent in their meanings. While the English version is generally interpreted to have ceded absolute sovereignty, the Māori version only cedes governorship. Practically, in the years since 1840, the English interpretation was generally privileged. Thus, New Zealand officially became a British colony and was ruled by a governor until 1852, when the British government passed the New Zealand Constitution Act 1852.[14] This Act established settler self-government in New Zealand by the way of a bi-cameral Parliament consisting of an appointed Legislative Council and a House of Representatives.[15] Following this, the first government was elected using a simple first-past-the-post electoral system, with single and multi-member districts.[16] Importantly, political franchise was only extended at this time to male land owners over the age of 21, which disqualified many Māori due to their communal ownership of land.[17] Furthermore, no women were extended the right to vote. However this changed in 1893 when New Zealand became the first self-governing country in the world to allow women the right to vote.[18]

Establishment of Māori electorates

[edit]In response to Māori antagonism towards the governments of the time due to their general lack of franchise, in 1867 the Māori Representation Act was passed, which established four additional Māori electorates throughout the country.[19] Each of these would each elect a single member to Parliament,[19] who was mandated to be full blooded Māori. However, all Māori males over the age of 21 were allowed to vote in these electorates regardless of their bloodline. Initially, these seats were created on an interim basis with a provision for their removal after five years had passed. Despite this, the Māori seats have remained even to this day as a part of the New Zealand political framework and have even been expanded in the Electoral Act 1993.[20]

Introduction of universal suffrage

[edit]Universal male suffrage was introduced in 1879 by the passing of the Qualification of Electors Act, which abolished the previous requirement to own land.[21] As such, all European men aged over 21 were now eligible to vote in New Zealand's elections. The only qualifiers to this were that to be eligible to vote, one must have resided in New Zealand for 12 months and in a specific electorate for 6 months. This had an immediate and profound effect on the number of registered voters as they rose from 82,271 (71%) of the adult European population in 1879 to 120,972 (91%) in 1881.[21] Furthermore, this allowed for election of people of different class to Parliament, including many 'working men'.[21]

Under huge pressure from suffrage campaigners led by Kate Sheppard, universal women's suffrage followed in 1893 with the passing of the Electoral Act 1893.[22] With this, New Zealand became the first self-governing nation in the world to grant women the vote.[18] However, women still had not gained the right to stand for Parliament.[22] Women's suffrage only allowed women to vote for existing male candidates and as such, there was still a great deal of progress required until women had the same legal rights as men in these regards.

Second-ballot system 1908–1913

[edit]The second-ballot system was introduced in the Second Ballot Act 1908 and was one of the first substantive reforms to the mechanism by which winning candidates are elected to Parliament to be seen in New Zealand.[3] This system modified the original first-past-the-post electoral system to require the winning candidate in each electorate to have gained over 50% of the overall votes cast within their constituency. When the leading candidate did not achieve this, a second ballot would be held a week later featuring only the two leading candidates, to assure an absolute majority of votes was achieved. This method is otherwise known as runoff voting. However, this system only remained in place for five years as it was abolished in 1913 due to its supposed inequitable nature in the emerging party environment of Parliament.[3]

Return to first past the post

[edit]Subsequently, New Zealand elections from 1914 to 1993 returned to the first-past-the-post system for parliamentary elections. However, in the newfound party context that had solidified throughout the second-ballot era it had somewhat unforeseen effects. While initially three main parties existed (the Liberal, Reform and Labour parties), the system quickly solidified into a two party system wherein the Reform and Liberal parties combined to create the National Party to oppose the Labour Party.[23] This ushered in an era wherein National and Labour parties dominated New Zealand politics, with only a small number of independent and other party candidates being elected.

Debates around electoral reform

[edit]This ushered in an era of relative stability for many years, until the electoral reform debate began in earnest following two successive general elections in 1978 and 1981 in which the National Party won a majority in Parliament with less than 40% of the vote and a lower overall share of the vote than the opposing Labour Party.[24] Other examples of this are evident in both the 1911 and 1931 elections.[24] Furthermore, the Social Credit Party was a victim of disproportionality as while they won 16.1% of the vote in 1978 and 20.7% of the vote in 1981, they only won one and two seats in Parliament respectively.[25]

In its 1984 campaign platform, the Labour party committed itself to appoint a royal commission on electoral reform if elected.[26] Labour won that election and in 1985 Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Justice Geoffrey Palmer established a Royal Commission on the Electoral System. Palmer had promoted proportional representation as a law professor in his book Unbridled Power?, also published in 1984. The Royal Commission's 1986 report, entitled Towards a Better Democracy recommended the adoption of an MMP electoral system.[10] Recognising that a parliament dominated by the major parties might fail to implement a sweeping reform of this sort, the commission also proposed a referendum on the issue.[10]

Ambivalence by the major parties and party politics led the issue to languish for several years, but in the meantime, an influential lobby group which had been formed, the Electoral Reform Coalition, continued to press for implementation of the royal commission’s proposals. During the 1987 election campaign, Labour promised to hold a referendum on MMP at, or before, the next election. Although Labour was returned to power in that election, it failed to proceed further on the matter due to its own internal divisions. In May 1990, Labour MP John Terris submitted a private members bill to force a binding referendum on the electoral system, but the bill was defeated.[27]

Sensing Labour’s vulnerability on the issue, the National opposition criticised the government inaction, and National Party Leader Jim Bolger promised to carry on with a referendum if elected in 1990 and do so before the next election in 1993.[28] Although there was even less support for reform among National parliamentarians than in the Labour Party, the new National government elected in 1990 was, like its predecessor, stuck with a rashly made campaign promise.[29]

1992 electoral system referendum

[edit]In 1992, a non-binding referendum was held on whether or not FPP should be replaced by a new, more proportional voting system. New Zealanders voted overwhelmingly for change and indicated an overwhelming preference for MMP.

Voters were asked two questions: whether or not to replace FPP with a new voting system; and which of four different alternative systems should be adopted instead (see question one and question two, below). The government appointed a panel chaired by the Ombudsman to oversee the campaign. The panel issued a brochure describing each of the voting systems appearing on the ballot, which was delivered to all households, and sponsored other publications, television programs, and seminars to inform the public. Meanwhile, the Electoral Reform Coalition campaigned actively in favour of the MMP alternative originally recommended by the royal commission. These measures made it possible for voters to make an informed choice on what was otherwise a complicated issue.

This led New Zealanders to vote overwhelmingly for change (84.7%) and to indicate a clear and overwhelming preference for the MMP alternative (70.5%). Such a result could not be ignored by the government, but rather than implementing MMP as the government was urged to do by the Electoral Reform Coalition, it opted to hold a second binding referendum on reform. This referendum featured a direct choice between FPP and MMP and was planned to be held to coincide with the next general election in 1993.

Question one in the 1992 referendum

[edit]The first question asked voters if they wished to retain FPP or change electoral systems. The result was 84.7% favour of replacing FPP, and 15.3% against.[11]

| Voting method referendum, 19 September 1992: Part A Choose one proposal: | |||

| Response | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Retain FPP I vote to retain the present First Past The Post system. |

186,027 | 15.28 | |

| Change System I vote for a change to the electoral system |

1,031,257 | 84.72 | |

| Total votes | 1,217,284 | 100.00 | |

| Turnout | |||

Source: Nohlen et al.

Question two in the 1992 referendum

[edit]The second question asked voters which new system should replace FPP. Voters could choose between the following (as listed on the ballot):

- Mixed Member Proportional (MMP); also known as the seat linkage compensatory mixed system used in Germany (there called personalized proportional representation, and later under the name "additional member" system adopted in Scotland, and Wales); in which roughly half of the seats are elected by FPP; and the remainder are filled from party lists to top-up the local seats so as to ensure a proportional overall result;

- Single Transferable Vote (STV); a proportional system used in the Republic of Ireland, Malta, the Australian Senate, Northern Ireland, lower houses in Tasmania and ACT, and upper houses in NSW, South Australia, Victoria and Western Australia; in which the country or province or state is divided into multimember constituencies; and each voter casts a single vote and ranks candidates in declining order of preference;[30]

- "Supplementary Member" system (SM); commonly called the Parallel voting system, used in Japan, Russia and Italy; a semi-proportional mixed system with list proportional representation used to fill some seats; and a larger proportion of seats elected by FPP.

- "Preferential Voting" (PV); used in Australia and Fiji elections; similar to FPP but with voters ranking candidates in descending order of preference in single-seat constituencies (also called Instant-Runoff Voting).

As noted earlier, an overwhelming majority of those favouring a new electoral system voted for MMP. The percentages of the vote cast for the four possible electoral system options offered in the second question were:

| Voting method referendum, 19 September 1992: Part B Choose one option: | |||

| Response | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| valid | total | ||

| Preferential Voting (PV) I vote for the Preferential Voting system (PV) |

73,539 | 6.56 | 6.04 |

| Mixed Member Proportional (MMP) I vote for the Mixed Member Proportional system (MMP) |

790,648 | 70.51 | 64.95 |

| Supplementary Member (SM) I vote for the Supplementary Member system (SM) |

62,278 | 5.55 | 5.12 |

| Single Transferable Vote (STV) I vote for the Single Transferable Vote system (STV) |

194,796 | 17.37 | 16.00 |

| Total valid votes | 1,121,261 | 100.00 | 92.11 |

| Invalid/blank votes | 96,023 | – | 7.89 |

| Total votes cast | 1,217,284 | – | 100.00 |

| Turnout | |||

Source: Nohlen et al.

1993 electoral referendum

[edit]

The second, binding, referendum was held in conjunction with the general election on 6 November 1993. Although reform had been strongly favoured by the electorate in 1992, the campaign in the second referendum was hard fought, as opposition to the reforms came together under an umbrella organisation called Campaign for Better Government (CBG).

Many senior politicians in both major parties and businesspeople were opposed to MMP: Bill Birch, then a senior National Cabinet Minister, had said MMP would be "a catastrophic disaster for democracy", and Ruth Richardson, former Minister of Finance in Jim Bolger's government said MMP "would bring economic ruin". Peter Shirtcliffe, chairman of Telecom New Zealand at the time and leader of the CBG, said MMP "would bring chaos".[31]

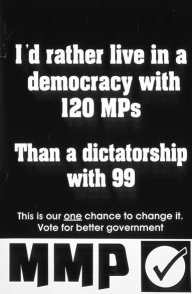

The Electoral Reform Coalition (ERC) was the main advocate for the adoption of MMP, and had support from several people, including the Green Party co-leader Rod Donald. MMP faced an uphill battle, as acknowledged in the pro-MMP poster to the side, since the proposed model was for increase in the number of MPs from 99 to 120. The CBG responded to the proposed increase in the number of MPs with a controversial television advertisement showing 21 faceless list MPs with paper bags over their heads.[32]

The ERC also had a "David and Goliath" battle financially. With the CBG being backed by a large business lobby, they had large amounts of money to spend. While the CBG could spend large on television, radio and full-page newspaper advertisements, often with fear-evoking graphic images, the ERC had limited funds and concentrated more on advocating in communities.[33]

At the same time, the country's largest newspaper, The New Zealand Herald, came out in support of the MMP proposal in the last week of the campaign, and press coverage overall was extensive and largely favourable. The Alliance heavily supported MMP, featuring "vote MMP" on all of its election billboards.[33]

It was the combination of growing public anger with the operation of the political system and the successful efforts of the Electoral Reform Coalition to harness that dissatisfaction in the cause of electoral reform that proved crucial. [...] Politicians subsequently acquiesced as they lost control of the referendum process because to have done otherwise would have courted the full wrath of a public incensed by their own impotence in the face of years of broken promises.

The CBG's backing of business leaders and politicians proved to be damaging to their cause, giving the impression that they were "a front for the business roundtable".[33] The ERC capitalised on severe disenchantment with New Zealand's political class after the severe effects of the neoliberal reforms of Rogernomics and Ruthanasia. After three elections in a row in which the parties that won power broke their promises and imposed unpopular market-oriented reforms,[35][36] the New Zealand public came to see MMP as a way to curb the power of governments to engage in dramatic and unpopular reforms. Cartoonist Murray Ball reflected this perception in a cartoon starring his characters Wal Footrot and Dog, with Wal telling The Dog (and by extension the viewer), "Want a good reason for voting for MMP? Look at the people who are telling you not to..."[37]

Given the link between the success of the referendum and anger at the status quo, politicians took lesser roles in the 1993 campaign, realising that their opposition to reform only increased voters' desire for change.[34]

In the face of a strong opposition campaign, the final result was much closer than in 1992, but the reforms carried the day, with 53.9% of voters in favour of MMP. ERC spokesperson Rod Donald reflected in 2003, "Had the referendum been held a week earlier I believe we would have lost."[33] Lending additional legitimacy to the second referendum was the increase in the participation rate, which went from 55% in the 1992 referendum to 85% in the second one. The law had been written so that MMP came automatically into effect upon approval by the electorate, which it did.

| Voting method referendum, 6 November 1993 Choose one proposal: | |||

| Response | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| First Past the Post (FPP) I vote for the present First Past the Post system as provided by the Electoral Act 1956 |

884,964 | 46.14 | |

| Mixed Member Proportional (MMP) I vote for the proposed Mixed Member Proportional system as provided by the Electoral Act 1993 |

1,032,919 | 53.86 | |

| Total votes | 1,917,833 | 100.00 | |

| Turnout | 82.61% | ||

Source: Nohlen et al.

Noteworthy in understanding the New Zealand case is that the reforms were able to go forward on the basis of majority support. This stands in contrast to the 60% requirement imposed in some other cases, such as the 2005 referendum on this issue in the Canadian province of British Columbia that failed despite a vote of 57.69% in support of the reform. Late in the campaign, Peter Shirtcliffe had in fact sought to act on this and proposed that the referendum should require a majority of the whole electorate, not just those voting, to pass the reform, which the government rejected.[34]

Introduction of MMP

[edit]The first election using the MMP system was held in 1996. Districts were re-drawn as in this election there were 34 fewer district members than had been elected in the 1993 election. As well, the Parliamentary seating had to be reconfigured as overall there were to be 21 more members than had been elected in 1993.

Under MMP, each voter has two votes: the first vote is called the party vote and voters use this vote to express their support for a particular party.[38] The second vote is the electorate vote, which is used to express support for a candidate to represent the voter's electorate in Parliament.[39]

New Zealand's MMP system allocates top-up seats only to parties that have achieved an electoral threshold of 5 percent of the nationwide party vote, or success in an electorate, to ensure their proportion of the seat is about equal to its vote share. Parties who meet this threshold are entitled to a share of the seats in Parliament that is about the same as its share of the nationwide vote.[38] If the number of its district seats are less than its vote share, it is allocated top-up seats. (Parties who do not exceed this threshold and who do not win at least one electorate seat receive no compensation for being under-represented. Those with less than .8 percent of the vote are not due any seats, of course.)

For example, if a party gets 30% of the party vote it is due roughly 36 MPs in Parliament (being 30% of 120 seats). If that party won 20 electorate seats, it will receive 16 List MPs in addition to its 20 Electorate MPs.

Because the system is proportional, it is difficult for any single party to gain a majority in Parliament alone. Therefore, coalitions or agreements between political parties are usually needed before Governments can be formed. The 2017 Election is a good example of this, resulting in a Labour-led government with coalitions with New Zealand First and the Greens.

Under the FPP, the two main parties had taken the lion's share of the seats in 1993. The National party had taken majority government in 1993 with only 35 percent of the vote. Under MMP the result was much more proportional. The National Party was again the leading party and again took about 35 percent of the vote but this time won only 44 seats out of 120. Six parties won seats in the chamber compared to four under FPP in 1993. Such wide representation would be produced by MMP in every election until 2017.

The 5% threshold has been criticised as a significant problem for minor parties, and impedes their ability to gain seats in Parliament. (In 2017 the Opportunities party took more than 2 percent of the vote and was due two seats proportionally but took none. About 6 percent of the vote in that election did not deliver any representation.) This has led to proposals to lower the percentage threshold.[40]

Coalition governments were rare, but not impossible under the FPP system. Most of the time a single party won majority government even if it did not win a majority of the vote. The majority governments elected in New Zealand have been mostly false-majority governments. Not since 1935 has a government been elected by a majority of the votes.

As an example of a coalition government under FPP, in 1931–35 there was the United/Reform coalition. Following the 1996 general election it took six weeks to form a coalition, showing that this is not a quick process.[41]

MMP is arguably a more democratic system than FPP. Supporters of MMP criticised FPP for creating elective dictatorships, and promoting the excessive power of one party government. Supporters consider MMP to provide increased representational fairness, and better-considered, wiser, and more moderate policies because of cooperation of the leading party and minority parties.

Furthermore, MMP is considered to increase the representation of a diverse population, enabling a higher percentage of Maori, women, Pasifika and Asian people in Parliament.

However, supporters of FPP believe FPP provides a more stable Parliament, and avoids a minority party "kingmaker", as was the case in 2017 with New Zealand First determining who would lead the government.[42]

Prior to the switch to MMP, New Zealand largely had a two party system, with government interchanging between Labour and National since 1935.

Under MMP, National and Labour lost their complete dominance in the House, with the 2020 election – the ninth since the introduction of MMP – being the first to give a single political party a majority of the seats (with very close to a majority of the votes). This had meant that electoral results have usually required political parties to form coalitions to govern. Indeed, since 1998 there have been minority coalition governments relying on supply and confidence from parties outside of government.

With the introduction of MMP, due to New Zealand's unique provision for parties to win list seats if they win at least one local seat despite getting less than the 5% threshold, there has been a widening of political parties represented within the House.

Prior to the 1996 election, there were four parties in the chamber. After the switch to MMP, the 1996 election gave seats in Parliament to six parties. The Act New Zealand party and United New Zealand was elected to Parliament for first time, joining the earlier elected Alliance, National, New Zealand First and Labour parties. Within a few years eight parties had seats in the chamber, after the Greens separated from the Alliance for the 1999 election, and after the creation of the Māori Party in 2004, and with the continued use of MMP.

The number of political parties was then expected to fall [43](as happened in Germany after its adoption of MMP), but instead seven or eight parties consistently had seats (see the table below). This was the case until the 2017 election where the number of parties in Parliament fell to five, the lowest it has been since MMP was introduced.

The 2017 election saw a severe decrease in the vote share for the two larger minor parties that were returned to parliament. This could be attributed to political scandals[44] and the popularity of the Labour leader candidate, Jacinda Ardern, and evidence of the beginning of an overall decline.

The transition to MMP increased the democratic accountability and tightened the relationship between votes cast and the seats. The change decreased the disproportionality of New Zealand's elections.[45]

| Election | Disproportionality[46] | Number of Parties in Parliament |

|---|---|---|

| 1972 | 12.06 | 2 |

| 1975 | 12.93 | 2 |

| 1978 | 15.55 | 3 |

| 1981 | 16.63 | 3 |

| 1984 | 15.40 | 3 |

| 1987 | 8.89 | 2 |

| 1990 | 17.24 | 3 |

| 1993 | 18.19 | 4 |

| MMP introduced | ||

| 1996 | 3.43 | 6 |

| 1999 | 2.97 | 7 |

| 2002 | 2.37 | 7 |

| 2005 | 1.13 | 8 |

| 2008 | 3.84 | 7 |

| 2011 | 2.38 | 8 |

| 2014 | 3.72 | 7 |

| 2017 | 2.73 | 5 |

| 2020 | 4.15 | 5 |

| 2023 | 2.63 | 6 |

2011 referendum

[edit]As part of the lead-up to the 2008 general election, the National Party promised a second referendum to decide whether or not to keep MMP. Upon gaining power, the party legislated that the referendum would be held alongside the 2011 general election, which took place on Saturday 26 November 2011. The referendum was similar to the 1992 referendum, in that voters were asked firstly to choose whether to keep the MMP system or to change to another system, and secondly to indicate which alternative system would, in the case of change, have their preference.

Nearly 58% of voters voted to keep the MMP system in preference to any of the other four options, compared to 1993, where just under 54% had favoured MMP in preference to keeping FPP. On the second question, nearly one-third of voters didn't vote, or cast an invalid vote. Of those who did vote, nearly 47% favoured the former FPP system. In Part A, 57.8 percent of valid votes were in favour of keeping the MMP system, with 42.2 percent in favour of change. Around three percent of the votes were informal. Compared to the 1993 referendum, there was a 3.9 percent increase in support for the MMP system.

In terms of electorates, 56 voted in majority to keep MMP while 14 voted in majority to change system. The seven Maori electorates had the largest votes in favour of keeping MMP, with Waiariki having the highest percentage in favour – 85.5 percent.[47] Clutha-Southland had the highest percentage in favour of change – 55.4 percent.[47]

| Response | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| valid | total | ||

I vote to keep the MMP voting system |

1,267,955 | 57.77 | 56.17 |

I vote to change to another voting system |

926,819 | 42.23 | 41.06 |

| Total valid votes | 2,194,774 | 100.00 | 97.23 |

| Informal votes | 62,469 | – | 2.77 |

| Total votes | 2,257,243 | – | 100.00 |

| Turnout | 73.51% | ||

| Electorate | 3,070,847[49] | ||

| Response | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| valid | total | ||

| First Past the Post (FPP) I would choose the First Past the Post system (FPP) |

704,117 | 46.66 | 31.19 |

| Preferential Voting (PV) I would choose the Preferential Voting system (PV) |

188,164 | 12.47 | 8.34 |

| Single Transferable Vote (STV) I would choose the Single Transferable Vote system (STV) |

252,503 | 16.30 | 11.19 |

| Supplementary Member (SM) I would choose the Supplementary Member system (SM) |

364,373 | 24.14 | 16.14 |

| Total valid votes | 1,509,157 | 100.00 | 66.86 |

| Informal votes | 748,086 | – | 33.14 |

| Total votes cast | 2,257,243 | – | 100.00 |

| Turnout | 73.51% | ||

| Electorate | 3,070,847[49] | ||

2012 review

[edit]On the back of the majority of voters voting to keep the MMP system, a review into the workings of the system by the Electoral Commission was automatically triggered. The Commission released a public consultation paper on 13 February 2012 calling for public submissions, with particular emphasis placed on six key areas. On 13 August 2012, the Commission released its proposal paper, recommending changes to some of the six areas.[50] After submissions on the proposals were considered, the final report was presented to the Minister of Justice on 29 October 2012.[51][52] It is up to Parliament to decide whether to enact any of the recommendations.[53]

| Area | August proposals | October report |

|---|---|---|

| Basis of eligibility for list seats |

|

As August; also

|

| By-election candidacy | Status quo: sitting list MPs can stand in electorate by-elections | As August |

| Dual candidacy | Status quo: someone on the party list can simultaneously stand in an electorate | As August |

| Ordering of party lists | Status quo: closed list rather than open list | As August; also

|

| Overhang seats | Abolishing the provision of overhang seats for parties not reaching the threshold. The extra electorates would be made up at the expense of list seats to retain 120 MPs | Abolish, provided the one-electorate-seat threshold is abolished |

| Proportionality | Identifying reduced proportionality as a medium-term issue, with it unlikely to be affected until electorate MPs reach 76, around 2026 based on 2012 population growth. | Consideration should be given to fixing the ratio of electorate seats to list seats at 60:40 to help maintain the diversity of representation and proportionality in Parliament obtained through the list seats. |

2024 Independent Electoral Review

[edit]In response to generally declining voter turnout, a number of commentators have proposed changes to the electoral system.

Former Prime Minister of New Zealand, Geoffrey Palmer, has expressed support for the introduction of compulsory voting in New Zealand, as has existed in Australia since 1924.[54] It is believed that such a measure will improve democratic engagement, although former Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern opposed it on the grounds that citizens should vote because they're engaged, not because they are compelled to.[55]

Palmer has also expressed support for lowering the voting age to 16, considering that this may provide a platform for increased civic education during high school years.[54]

In October 2021, the Labour government initiated a review of aspects of New Zealand's electoral law.[56] The Independent Electoral Review Panel was established in May 2022[57] and has its own website.[58]

The Ministry of Justice published the final report of the Independent Electoral Review on 16 January 2024.[59][60] The new National Party justice minister Paul Goldsmith ruled out implementing changes such as lowering the voting age to 16, allowing prisoners to vote, and increasing the size of parliament.[61]

Local government elections

[edit]Up until the 2004 local elections, all territorial authorities were elected using the bloc vote (although often referred to as first-past-the-post). In 2004, at the discretion of the council, they could use the single transferable vote. Eight local bodies used STV in the 2007 local body elections.[62] However, only five territorial authorities used STV in the 2013 local elections.[63]

Almost all regional authorities in New Zealand use FPP. However the Greater Wellington Regional Council used STV for the first time in the 2013 elections, becoming the first time that a regional authority used STV.[63]

Before their abolition, all district health boards used STV.[63]

In February 2021, the government passed the Local Electoral (Māori Wards and Māori Constituencies) Amendment Act which removed the option for citizens to require a local poll to decide whether the council should establish a Māori ward.[64] The poll option had been seen as a barrier to establishing Māori wards. Twenty-four councils had sought to establish Māori wards since 2002 and only two had been successful.[65] The government enacted the change against advice from the Department of Internal Affairs, which recommended more time was provided to consult on the change.[66]

See also

[edit]- Constitution of New Zealand

- Elections in New Zealand

- Electoral system of New Zealand

- History of voting in New Zealand

- Political funding in New Zealand

References

[edit]- ^ "New Zealand's first general election begins". NZHistory. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Archived from the original on 24 May 2018. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- ^ Martin, John E. (29 January 2016). "Political participation and electoral change in nineteenth-century New Zealand". New Zealand Parliament. Archived from the original on 23 May 2018. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- ^ a b c d Foster, Bernard John (1966). "Government – Parliamentary Elections: Second Ballot System (1908–13)". In McLintock, A. H. (ed.). An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 23 May 2018. Retrieved 23 May 2018 – via Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

- ^ "FPP – First Past the Post". Electoral Commission. Archived from the original on 21 May 2018. Retrieved 20 May 2018.

- ^ "Quick history". Archived from the original on 23 May 2018. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- ^ Report of meeting on "Proportional representation," or effective voting, held at River House, Chelsea, on Tuesday, July 10th 1894. Addressed by Miss Spence, Mr. Balfour, Mr. Courtney, Sir John Lubbock, and Sir John Hall. 1894. pp. 30–31.

- ^ "MMP – Mixed Member Proportional". Electoral Commission. Archived from the original on 21 May 2018. Retrieved 20 May 2018.

- ^ a b "Reasons for change: Election results". janda.org. Archived from the original on 1 June 2016. Retrieved 20 May 2018.

- ^ Fitzgerald v Muldoon and Others [1976] 2 NZLR 615

- ^ a b c "Report of the Royal Commission on the Electoral System 1986". New Zealand Electoral Commission. 11 December 1986. Archived from the original on 10 January 2018. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- ^ a b Nohlen, D, Grotz, F & Hartmann, C (2001) Elections in Asia: A data handbook, Volume II, p723 ISBN 0-19-924959-8

- ^ Taonga, New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage Te Manatu. "Results of the 1993 referendum on the electoral system". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 24 May 2018. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- ^ Taonga, New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage Te Manatu. "1. – Nation and government – Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 24 May 2018. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ^ Taonga, New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage Te Manatu. "2. – Nation and government – Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 23 October 2020. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ^ "New Zealand Constitution Act 1852 – Archives New Zealand. Te Rua Mahara o te Kāwanatanga". archives.govt.nz. Archived from the original on 1 April 2019. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ^ "New Zealand Constitution Act 1852 – Archives New Zealand. Te Rua Mahara o te Kāwanatanga". archives.govt.nz. Archived from the original on 1 April 2019. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ^ Taonga, New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage Te Manatu. "1. – Voting rights – Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 25 May 2018. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ^ a b "New Zealand women and the vote – Women and the vote | NZHistory, New Zealand history online". nzhistory.govt.nz. Archived from the original on 24 February 2020. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ^ a b Moon, Paul (2013). "'A Proud Thing To Have Recorded' : The Origins and Commencement of National Indigenous Political Representation in New Zealand through the 1867 Maori Representation Act". Journal of New Zealand Studies. 13: 52–65.

- ^ "Features (pre 2016)". Archived from the original on 24 May 2018. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ^ a b c "Universal male suffrage introduced | NZHistory, New Zealand history online". nzhistory.govt.nz. Archived from the original on 16 January 2018. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ^ a b "Brief history – Women and the vote | NZHistory, New Zealand history online". nzhistory.govt.nz. Archived from the original on 24 October 2016. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ^ Taonga, New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage Te Manatu. "2. – Political parties – Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 24 May 2018. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ^ a b "Research papers". Archived from the original on 14 September 2018. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- ^ "General elections 1890–1993". Electoral Commission. Archived from the original on 30 December 2015. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ^ For a good summary background on the referendum, see pp. 3–5 in LeDuc, Lawrence; et al. "The Quiet Referendum: Why Electoral Reform Failed in Ontario" (PDF). University of Toronto. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 November 2014. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ MMP Or SM? A Big Decision Looms For New Zealand Voters Archived 1 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine scoop.co.nz, 30 June 2011

- ^ Vowles, Jack (January 1995). "The Politics of Electoral Reform in New Zealand". International Political Science Review. um 16, no 1: 96.

- ^ pp. 3–4 in LeDuc, Lawrence; et al. "The Quiet Referendum: Why Electoral Reform Failed in Ontario" (PDF). University of Toronto. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 November 2014. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Farrell and McAllister, The Australian Electoral System, p. 50-51

- ^ "Decision Maker – MMP's First Decade". 2006. Archived from the original on 16 October 2008. Retrieved 5 February 2009.

- ^ "Cartoon from the MMP campaign – Government and Politics". Archived from the original on 2 June 2010. Retrieved 6 July 2011.

- ^ a b c d Donald, Rod (21 August 2003). "Proportional Representation in NZ – how the people let themselves in". Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 6 July 2011.

- ^ a b c Renwick, Alan (2010). The Politics of Electoral Reform: Changing the Rules of Democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 207. ISBN 978-0-521-76530-5. Archived from the original on 15 March 2022. Retrieved 22 July 2016.

- ^ Eyley, Claudia Pond; Salmon, Dan (2015). Helen Clark: Inside Stories. Auckland: Auckland University Press. pp. 145–146. ISBN 978-1-77558-820-7. Archived from the original on 15 February 2017. Retrieved 20 July 2016.

- ^ Jack Vowles (2005). "New Zealand: The Consolidation of Reform?". In Gallagher, Michael; Mitchell, Paul (eds.). The Politics of Electoral Systems. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 296–297. ISBN 978-0-19-925756-0. Archived from the original on 28 April 2022. Retrieved 22 July 2016.

- ^ Ball, Murray (1993). "Pro-MMP poster" (poster). Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 16 August 2016. Retrieved 4 July 2016.

- ^ a b "MMP Voting System". Electoral Commission. Archived from the original on 24 September 2014. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- ^ "MMP". Electoral Commission. Archived from the original on 19 September 2014. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- ^ "It's time to ditch the MMP threshold". Stuff. 2 October 2017. Archived from the original on 22 May 2018. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- ^ "Coalition and Minority Governments". Parliamentary Library. 23 November 1999. Archived from the original on 10 June 2016. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ^ Nagel, Jack (2012). "Evaluating democracy in New Zealand under MMP". Policy Quarterly. 8 (2): 3–11. doi:10.26686/pq.v8i2.4412.

- ^ Vowles. Coffe. Curtin, Jack. Hilde. Jennifer (2017). A Bark but No Bite: Inequality and the 2014 New Zealand general election. ANU Press.

- ^ "Metiria Turei bows out". Radio New Zealand. 24 September 2017. Archived from the original on 12 May 2018. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ^ Jonathan Boston, Stephen Church, Stephen Levine, Elizabeth McLeay and Nigel Roberts, New Zealand Votes: The General Election of 2002 Wellington: Victoria University Press, 2003

- ^ "Election indices" (PDF). Gallagher Index. 2 February 2024. p. 34. Retrieved 7 July 2024.

- ^ a b "Results by Electorate for the 2011 Referendum on the Voting System". New Zealand Electoral Commission. 10 December 2011. Retrieved 16 May 2018.

- ^ a b "2011 Referendum on the Voting System Preliminary Results for Advance Votes". Electoral Commission. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- ^ a b "Enrolment statistics for the whole of New Zealand". Electoral Commission. 26 November 2011. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- ^ "Review of the MMP voting system: Proposals Paper" (PDF). Electoral Commission. 13 August 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 September 2012. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- ^ "MMP review details". Television New Zealand. 13 February 2012. Archived from the original on 15 February 2012. Retrieved 16 February 2012.

- ^ Electoral Commission New Zealand. "Report of the Electoral Commission on the Review of the MMP Voting System, 29 October 2012" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 February 2014. Retrieved 25 January 2014.

- ^ Electoral Commission New Zealand. "The Results of the MMP Review". Archived from the original on 7 July 2014. Retrieved 25 January 2014.

- ^ a b Palmer, Geoffrey; Butler, Andrew (2018). Towards Democratic Renewal. Wellington: Victoria University Press. p. 226.

- ^ brian.rudman@nzherald.co.nz, Brian Rudman Brian Rudman is a NZ Herald feature writer and columnist (11 April 2017). "Brian Rudman: Compulsory voting not the answer to low turnout". The New Zealand Herald. ISSN 1170-0777. Archived from the original on 25 May 2018. Retrieved 27 May 2018.

- ^ Fafoi, Kris. "Government to review electoral law". Beehive.govt.nz. NZ Government. Archived from the original on 19 October 2021. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- ^ "Independent panel appointed to review electoral law". The Beehive. Retrieved 6 September 2022.

- ^ "Independent Electoral Review Home". Electoral Review. Retrieved 6 September 2022.

- ^ "Recent Reviews and Electoral Reforms: Independent Electoral Review". New Zealand Ministry of Justice. Retrieved 2 July 2024.

- ^ Independent Electoral Review. "Final Report: Executive Summary" (PDF). New Zealand Ministry of Justice. Retrieved 2 July 2024.

- ^ Mathias, Shanti (17 January 2024). "Electoral review's major recommendations ruled out on release of final report". The Spinoff. Retrieved 14 September 2024.

- ^ "The Local Government Electoral Option 2008" (PDF). Department of Internal Affairs. Retrieved 22 December 2023.

- ^ a b c "STV Information". Department of Internal Affairs. Archived from the original on 1 October 2013. Retrieved 29 September 2013.

- ^ Mahuta, Nanaia. "Māori wards Bill passes third reading". Beehive.govt.nz. NZ Parliament. Archived from the original on 3 March 2021. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- ^ "Changes to 'fundamentally unfair' process to make way for Māori wards". Politics / Te Ao Māori. Radio New Zealand. Archived from the original on 1 February 2021. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- ^ Sachdeva, Sam. "Māori wards change was fast-tracked against official advice". Newsroom. Archived from the original on 11 May 2021. Retrieved 11 May 2021.