MEAI

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | none |

| Other names | 5-MeO-AI; 5-MeO-2-AI; 5-Methoxy-2-aminoindane; 5-Methoxy-2-aminoindan; Chaperon; CMND-100; CMND100 |

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | High[citation needed] |

| Metabolism | Acetyl-aminoindandane[citation needed] |

| Elimination half-life | Non-linear[citation needed] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

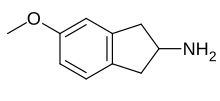

| Formula | C10H13NO |

| Molar mass | 163.220 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

MEAI, also known as 5-methoxy-2-aminoindane (5-MeO-AI), is a monoamine releasing agent of the 2-aminoindane group.[1] It specifically acts as a selective serotonin releasing agent (SSRA).[1] The drug is under development for the treatment of alcoholism, cocaine use disorder, metabolic syndrome, and obesity under the developmental code name CMND-100.[2]

Effects

[edit]When used recreationally, MEAI is reported to produce mild psychoactive effects and euphoria.[1]

Pharmacology

[edit]Pharmacodynamics

[edit]MEAI is a monoamine releasing agent (MRA).[1] It is a modestly selective serotonin releasing agent (SSRA), with 6-fold preference for induction of serotonin release over norepinephrine release and 20-fold preference for induction of serotonin release over dopamine release.[1] In addition to inducing monoamine neurotransmitter release, MEAI has moderate affinity for the α2-adrenergic receptor.[1] Based on these findings, MEAI might produce MDMA-like entactogenic and sympathomimetic effects but may be expected to have reduced misuse liability in comparison.[1]

| Compound | Monoamine release (EC50, nM) | Ref | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serotonin | Norepinephrine | Dopamine | ||

| 2-AI | >10,000 | 86 | 439 | [1] |

| MDAI | 114 | 117 | 1,334 | [1] |

| MMAI | 31 | 3,101 | >10,000 | [1] |

| MEAI | 134 | 861 | 2,646 | [1] |

| d-Amphetamine | 698–1,765 | 6.6–7.2 | 5.8–24.8 | [3][4][5][6][7] |

| MDA | 160–162 | 47–108 | 106–190 | [8][5][9] |

| MDMA | 50–85 | 54–110 | 51–278 | [3][10][11][8][9] |

| 3-MA | ND | 58.0 | 103 | [5] |

| Notes: The smaller the value, the more strongly the compound produces the effect. The assays were done in rat brain synaptosomes and human potencies may be different. See also Monoamine releasing agent § Activity profiles for a larger table with more compounds. Refs: [1] | ||||

Chemistry

[edit]MEAI, also known as 5-methoxy-2-aminoindane, is a 2-aminoindane derivative.[12] It is the 2-aminoindane analogue of the amphetamine 3-methoxyamphetamine.[12]

History

[edit]MEAI appears to have been first synthesized in 1956.[1] Its molecular structure was first mentioned implicitly in a markush structure schema appearing in a patent from 1998.[13] It was later explicitly and pharmacologically described in a peer reviewed paper in 2017 by David Nutt and Ezekiel Golan et al.[14] followed by another in February 2018 which detailed the pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics and metabolism of MEAI by Shimshoni, David Nutt, Ezekiel Golan et al.[15] One year later it was studied and reported on in another peer reviewed paper by Halberstadt et al.[16] The aminoindane family of molecules was, perhaps, first chemically described in 1980.[17][18]

Alcohol substitute

[edit]MEAI was an early candidate of alcohol replacement drugs that came to market during a late 2010s movement to replace alcohol with less-toxic alternatives spearheaded by British psychopharmacologist David Nutt[19][20][21] rippling to the rest of Europe.[22]

In an act of gonzo journalism, Michael Slezak writing for New Scientist, tried and reported on his experience with MEAI[23] after being provided with it by Dr Zee[24] (Ezekiel Golan) after an interview[23] Golan claimed he invented MEAI and originally intended MEAI to be sold as a legal high but instead indicated plans to work with David Nutt and his company DrugScience to develop MEAI further based on Golan's patents as a "binge behaviour regulator"[25] and "alcoholic beverage substitute".[26]

In 2018, a company named Diet Alcohol Corporation of the Americas (DACOA) began openly marketing an MEAI-based drink called "Pace" for sale in the USA and Canada. Pace was described as a 50ml bottle containing 160mg of MEAI in mineral water. Distribution halted after Health Canada released a warning indicating the substance was considered illegal to market for consumption in Canada due to structural similarity to amphetamine.[27][28] In a December 2018 article by CBC News, Ezekiel Golan (Dr Z/Dr Zee) was interviewed and publicly came out as the "lead scientist" of Pace claiming "tens of thousands" of bottles were already sold in Canada.[29] Golan claimed the MEAI featured in Pace was "manufactured in India" and "bottled in Delaware".[29] Health Canada provided a statement to CBC News stating "Pace is an illegal and unauthorized product in Canada." Both Chemistry World[30] and The BBC have dubbed Ezekiel Golan as "the man who invents legal highs".[31] The Guardian called him "the godfather of legal highs"[32] for his contribution in reintroducing substituted cathinone based drugs commonly sold as Bath salts (drug) including Mephedrone

Pharmaceutical development

[edit]On May 26, 2022, MEAI was prepared for FDA registration by Clearmind Medicine Inc.;[33][34][35] Clearmind Medicine claims wide intellectual property holdings to Ezekiel Golan's patents.[36][37][38][39] In March 2022 Clearmind Medicine announced supportive evidence from animal studies in mice attesting to suppression of alcohol consumption.[40] In June 2022 Clearmind Medicine announced promising results from animal studies that showed promise for treating cocaine addiction with MEAI.[41][42]

MEAI, under the developmental code name CMND-100, is under development by Clearmind Medicine for the treatment of alcoholism, cocaine use disorder, metabolic syndrome, and obesity.[2] As of October 2024, it is in the preclinical stage of development for these indications.[2]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Halberstadt AL, Brandt SD, Walther D, Baumann MH (March 2019). "2-Aminoindan and its ring-substituted derivatives interact with plasma membrane monoamine transporters and α2-adrenergic receptors". Psychopharmacology (Berl). 236 (3): 989–999. doi:10.1007/s00213-019-05207-1. PMC 6848746. PMID 30904940.

- ^ a b c "5-Methoxy 2-aminoindane". AdisInsight. 16 October 2024. Retrieved 24 October 2024.

- ^ a b Rothman RB, Baumann MH, Dersch CM, Romero DV, Rice KC, Carroll FI, Partilla JS (January 2001). "Amphetamine-type central nervous system stimulants release norepinephrine more potently than they release dopamine and serotonin". Synapse. 39 (1): 32–41. doi:10.1002/1098-2396(20010101)39:1<32::AID-SYN5>3.0.CO;2-3. PMID 11071707. S2CID 15573624.

- ^ Baumann MH, Partilla JS, Lehner KR, Thorndike EB, Hoffman AF, Holy M, Rothman RB, Goldberg SR, Lupica CR, Sitte HH, Brandt SD, Tella SR, Cozzi NV, Schindler CW (March 2013). "Powerful cocaine-like actions of 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV), a principal constituent of psychoactive 'bath salts' products". Neuropsychopharmacology. 38 (4): 552–562. doi:10.1038/npp.2012.204. PMC 3572453. PMID 23072836.

- ^ a b c Blough B (July 2008). "Dopamine-releasing agents" (PDF). In Trudell ML, Izenwasser S (eds.). Dopamine Transporters: Chemistry, Biology and Pharmacology. Hoboken [NJ]: Wiley. pp. 305–320. ISBN 978-0-470-11790-3. OCLC 181862653. OL 18589888W.

- ^ Glennon RA, Dukat M (2017). "Structure-Activity Relationships of Synthetic Cathinones". Curr Top Behav Neurosci. Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences. 32: 19–47. doi:10.1007/7854_2016_41. ISBN 978-3-319-52442-9. PMC 5818155. PMID 27830576.

- ^ Partilla JS, Dersch CM, Baumann MH, Carroll FI, Rothman RB (1999). "Profiling CNS Stimulants with a High-Throughput Assay for Biogenic Amine Transporter Substractes". Problems of Drug Dependence 1999: Proceedings of the 61st Annual Scientific Meeting, The College on Problems of Drug Dependence, Inc (PDF). NIDA Res Monogr. Vol. 180. pp. 1–476 (252). PMID 11680410.

RESULTS. Methamphetamine and amphetamine potently released NE (IC50s = 14.3 and 7.0 nM) and DA (IC50s = 40.4 nM and 24.8 nM), and were much less potent releasers of 5-HT (IC50s = 740 nM and 1765 nM). [...]

- ^ a b Setola V, Hufeisen SJ, Grande-Allen KJ, Vesely I, Glennon RA, Blough B, Rothman RB, Roth BL (June 2003). "3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, "Ecstasy") induces fenfluramine-like proliferative actions on human cardiac valvular interstitial cells in vitro". Molecular Pharmacology. 63 (6): 1223–1229. doi:10.1124/mol.63.6.1223. PMID 12761331. S2CID 839426.

- ^ a b Brandt SD, Walters HM, Partilla JS, Blough BE, Kavanagh PV, Baumann MH (December 2020). "The psychoactive aminoalkylbenzofuran derivatives, 5-APB and 6-APB, mimic the effects of 3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine (MDA) on monoamine transmission in male rats". Psychopharmacology (Berl). 237 (12): 3703–3714. doi:10.1007/s00213-020-05648-z. PMC 7686291. PMID 32875347.

- ^ Baumann MH, Ayestas MA, Partilla JS, Sink JR, Shulgin AT, Daley PF, Brandt SD, Rothman RB, Ruoho AE, Cozzi NV (April 2012). "The designer methcathinone analogs, mephedrone and methylone, are substrates for monoamine transporters in brain tissue". Neuropsychopharmacology. 37 (5): 1192–1203. doi:10.1038/npp.2011.304. PMC 3306880. PMID 22169943.

- ^ Marusich JA, Antonazzo KR, Blough BE, Brandt SD, Kavanagh PV, Partilla JS, Baumann MH (February 2016). "The new psychoactive substances 5-(2-aminopropyl)indole (5-IT) and 6-(2-aminopropyl)indole (6-IT) interact with monoamine transporters in brain tissue". Neuropharmacology. 101: 68–75. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2015.09.004. PMC 4681602. PMID 26362361.

- ^ a b Nichols DE, Marona-Lewicka D, Huang X, Johnson MP (1993). "Novel serotonergic agents". Drug des Discov. 9 (3–4): 299–312. PMID 8400010.

- ^ US 5708018, Haadsma-Svensson SR, Andersson BR, Sonesson CA, Lin CH, Waters RN, Svensson KA, Carlsson PA, Hansson LO, Stjernlof NP, "2-aminoindans as selective dopamine D3 ligands", published 1998-01-13, assigned to Pharmacia & Upjohn Co.

- ^ Shimshoni JA, Winkler I, Edery N, Golan E, van Wettum R, Nutt D (March 2017). "Toxicological evaluation of 5-methoxy-2-aminoindane (MEAI): Binge mitigating agent in development". Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 319: 59–68. Bibcode:2017ToxAP.319...59S. doi:10.1016/j.taap.2017.01.018. PMID 28167221. S2CID 205304106.

- ^ Shimshoni JA, Sobol E, Golan E, Ben Ari Y, Gal O (March 2018). "Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic evaluation of 5-methoxy-2-aminoindane (MEAI): A new binge-mitigating agent". Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 343: 29–39. Bibcode:2018ToxAP.343...29S. doi:10.1016/j.taap.2018.02.009. PMID 29458138. S2CID 3879333.

- ^ Halberstadt AL, Brandt SD, Walther D, Baumann MH (March 2019). "2-Aminoindan and its ring-substituted derivatives interact with plasma membrane monoamine transporters and α2-adrenergic receptors". Psychopharmacology. 236 (3): 989–999. doi:10.1007/s00213-019-05207-1. PMC 6848746. PMID 30904940.

- ^ Sainsbury PD, Kicman AT, Archer RP, King LA, Braithwaite RA (2011). "Aminoindanes--the next wave of 'legal highs'?". Drug Testing and Analysis. 3 (7–8): 479–482. doi:10.1002/dta.318. PMID 21748859.

- ^ Cannon JG, Perez JA, Pease JP, Long JP, Flynn JR, Rusterholz DB, Dryer SE (July 1980). "Comparison of biological effects of N-alkylated congeners of beta-phenethylamine derived from 2-aminotetralin, 2-aminoindan, and 6-aminobenzocycloheptene". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 23 (7): 745–749. doi:10.1021/jm00181a009. PMID 7190613.

- ^ Nutt D (23 October 2013). "Decision making about illegal drugs: time for science to take the lead". Nobel Forum, Karolinska Institutet – via YouTube.

- ^ Nutt DJ, King LA, Phillips LD (November 2010). "Drug harms in the UK: a multicriteria decision analysis". Lancet. 376 (9752). London, England: 1558–65. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61462-6. PMID 21036393. S2CID 5667719.

- ^ Forster K (24 September 2016). "Hangover free alcohol is finally here". The Independent. Retrieved 25 March 2022.

- ^ Wermter B (29 April 2019). "Rauschmittel und gesellschaftliche Probleme" [Drug related societal issues]. Benedict Wermter (in German).

- ^ a b Slezak M (30 December 2014). "High and dry? Party drug could target excess drinking". New Scientist. Retrieved 2022-10-16.

- ^ Slezak M (9 August 2014). "An Interview with Dr Z" (PDF). New Scientist. pp. 1–3. Retrieved 16 October 2022.

- ^ US 10406123B2, Golan E, "Binge behavior regulators", issued 2019-09-10

- ^ US 20170360067, Golan E, "Alcoholic beverage substitutes", issued 2017-12-21

- ^ "Advisory - Health Canada warns consumers that Pace, promoted as an alcohol substitute, is unauthorized and may pose serious health risks". Health Canada. 21 December 2018 – via CISION.

- ^ Brunet J (24 April 2019). "FACT CHECK: Is Pace, an "Alcohol Alternative," Legal in Canada?". The Walrus. Toronto, Ontario.

- ^ a b Wright J (8 December 2018). "Is this drink really a new 'alcohol alternative'?". Information Morning Saint John. pp. All. Retrieved 15 October 2022.

- ^ Extance A (6 September 2017). "The rising tide of 'legal highs'". Chemistry World. Retrieved 2022-10-17.

- ^ "Meet Dr. Zee - the man who invented legal highs". BBC. 23 January 2018.

- ^ Jonze T (24 May 2016). "Dr Zee, the godfather of legal highs: 'I test everything on myself'". TheGuardian.com.

- ^ "Clearmind Medicine". www.clearmindmedicine.com.

- ^ "Clearmind Medicine Inc". CSE:CMND.

- ^ וינרב, גלי (16 February 2022). "החברה שמנסה להפוך סם פסיכדלי למוצר נגד התמכרות" [The company trying to turn a psychedelic drug into an anti-addiction product]. Globes (in Hebrew).

- ^ US 10137096, Golan E, "Binge behavior regulators", published 2018-11-27

- ^ EP 3230256, Golan E, "Alcoholic beverage substitutes", published 2019-11-13

- ^ EP 3230255, Golan E, "Binge behavior regulators", published 2017-10-18

- ^ "The Science and IP Behind our Treatments". Clearmind.

- ^ "Clearmind Medicine". www.clearmindmedicine.com.

- ^ "Clearmind Medicine". www.clearmindmedicine.com. Retrieved 14 August 2022.

- ^ "Clearmind Medicine". www.clearmindmedicine.com. Retrieved 2022-10-16.