Critique of work

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding articles in German and Swedish. (May 2022) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

Critique of work or critique of labour is the critique of, or wish to abolish, work as such, and to critique what the critics of works deem wage slavery.[1][2][3]

Critique of work can be existential, and focus on how labour can be and/or feel meaningless, and stands in the way for self-realisation.[1][4][3] But the critique of work can also highlight how excessive work may cause harm to nature, the productivity of society, and/or society itself.[5][6][7] The critique of work can also take on a more utilitarian character, in which work simply stands in the way for human happiness as well as health.[8][2][1][9]

History

[edit]Many thinkers have critiqued and wished for the abolishment of labour as early as in Ancient Greece.[1][10][11][12] An example of an opposing view is the anonymously published treatise titled Essay on Trade and Commerce published in 1770 which claimed that to break the spirit of idleness and independence of the English people, ideal "work-houses" should imprison the poor. These houses were to function as "houses of terror, where they should work fourteen hours a day in such fashion that when meal time was deducted there should remain twelve hours of work full and complete."[11]

Views like these propagated for in the following decades by e.g. Malthus, which led up to the Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834.[11]

The battle of shortening the working hours to ten hours was ongoing between around the 1840s until about 1900.[10] However, establishing the eight-hour working day went significantly faster, and these short-hour social movements aligned against labour, managed to get rid of two working hours between the mid-1880s to 1919.[10] During this epoch, reformers argued that mechanization was not only supposed to provide material goods, but to free workers from "slavery" and introduce them to the "duty" to enjoy life.[10]

While the productive capacity rose enormously with industrialization, people were made busier, while one might have expected the opposite to occur.[10] This was at least the expectation among many intellectuals such as Paul Lafargue.[10] The liberal John Stuart Mill also predicted that society would come to a stage where growth would end when mechanization would meet all real needs.[10] Lafargue argued that the obsession society seemed to have with labour paradoxically harmed the productivity, which society had as one of its primary justifications for not working as little as possible.[1]

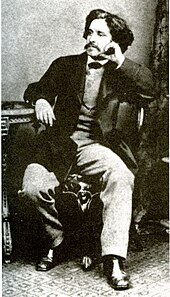

Paul Lafargue

[edit]In Lafargue's book The Right To Be Lazy, he claims that: "It is sheer madness, that people are fighting for the "right" to an eight-hour working day. In other words, eight hours of servitude, exploitation and suffering, when it is leisure, joy and self-realisation that should be fought for – and as few hours of slavery as possible."[1]

Automation, which had already come a long way in Lafargue's time, could easily have reduced working hours to three or four hours a day. This would have left a large part of the day for the things which he would claim that we really want to do – spend time with friends, relax, enjoy life, be lazy. The machine is the saviour of humanity, Lafargue argues, but only if the working time it frees up becomes leisure time. It can be, it should be, but it rarely has been. The time that is freed up is according to Lafargue usually converted into more hours of work, which in his view is only more hours of toil and drudgery.[1]

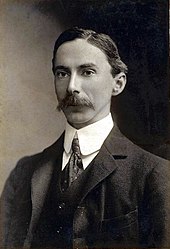

Bertrand Russell

[edit]Russell's book In Praise of Idleness is a collection of essays on the themes of sociology and philosophy. Russell argues that if the burden of work were shared equally among all, resulting in fewer hours of work, unemployment would disappear. As a result, human happiness would also increase as people would be able to enjoy their newfound free time, which would further increase the amount of science and art.[2] Russell for example claimed that "Modern methods of production have given us the possibility of ease and security for all; we have chosen, instead, to have overwork for some and starvation for others. Hitherto we have continued to be as energetic as we were before there were machines; in this we have been foolish".[13]

Contemporary era

[edit]David Graeber

[edit]The anthropologist David Graeber has written about bullshit jobs, which are jobs that are meaningless and do not contribute anything worthwhile, or even damage society.[14] Graeber also claims that bullshit jobs are often not the worst paid ones.[15]

The bullshit-jobs can include tasks like these:[16]

- Watching over an inbox which received emails merely to copy and paste them into another form.

- To be hired to look busy.

- Working with pushing buttons in an elevator.

- Make others look or feel important.

- Roles that exist merely because other institutions employ people in the same roles.

- Employees that merely solve issues that could be fixed once and for all, or automated away.

- People who are hired so that institutions can claim that they do something, which in reality they are not doing.

- Jobs where the most important thing is to sit in the right place, like working in a reception, and forwarding emails to someone who is tasked with reading them.

Frédéric Lordon

[edit]In Willing Slaves of Capital: Spinoza and Marx on Desire,[17] the French economist and philosopher Frédéric Lordon ponders why people accept deferring or even replacing their own desires and goals with those of an organization. "It is ultimately quite strange", he writes, "that people should so 'accept' to occupy themselves in the service of a desire that was not originally their own."[17] Lordon argues that surrender of will occurs via the capture by organizations of workers' "basal desire" – the will to survive.

But this willingness of workers to become aligned with a company's goals is due not only to what can be called "managerialism" (the ways in which a company co-opts individuality via wages, rules, and perks), but to the psychology of the workers themselves, whose "psyches… perform at times staggering feats of compartmentalization."[17] So consent to work itself becomes problematic and troubling; as captured in the title of Lordon's book, workers are "willing slaves."

Franco "Bifo" Berardi

[edit]Franco Berardi, an Italian Autonomist thinker, suggests in The Soul at Work: From Alienation to Autonomy,[18] that capitalism has harnessed modern desires for autonomy and independence:

No desire, no vitality seems to exist anymore outside the economic enterprise, outside productive labour and business. Capital was able to renew its psychic, ideological and economic energy, specifically thanks to the absorption of creativity, desire, and individualistic, libertarian drives for self-realization.

Knowledge workers, or what Barardi calls the "cognitariat" are far from free of this co-option. People in these jobs, he says, have suffered a kind of Taylorization of their work via the parceling and routinization of even creative activities.

George Alliger

[edit]In the 2022 book Anti-Work: Psychological Investigations into Its Truths, Problems, and Solutions,[19] work psychologist Alliger proposes to systematize anti-work thinking by suggesting a set of almost 20 propositions that characterize this topic. He draws on a wide variety of sources; a few of the propositions or tenets are:

- Work demands submission and is damaging to the human psyche.

- The idea that work is "good" is a modern and deleterious development.

- The tedious, boring, and grinding aspects of work characterize most of the time spent in many and probably even all jobs.

- Work is subjectively "alienating" and meaningless due to workers' lack of honest connection to the organization and its goals and outcomes.[19]

Alliger provides a discussion of each proposition and considers how workers, as well as psychologists, can best respond to the existential difficulties and challenges of work.

Guy Debord

[edit]One of the founders of the Situationist International in France (which helped inspire the student revolt of 1968), Guy Debord wrote the influential The Society of the Spectacle (La société du spectacle).[20] He suggested that since all actual activity, including work, has been harnessed into the production of the spectacle, that there can be no freedom from work, even if leisure time is increasing.[21] That is, since leisure can only be leisure within the planned activities of the spectacle, and since alienated labour helps to reproduce that spectacle, there is also no escape from work within the confines of the spectacle.[21][22] Debord also used the slogan "NEVER WORK", which he initially painted as graffiti, and henceforth came to emphasize "could not be considered superfluous advice".[23]

Anti-work ethic

[edit]History

[edit]

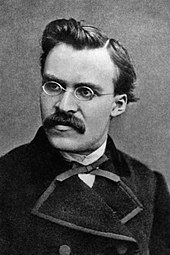

Friedrich Nietzsche rejected the work ethic, viewing it as damaging to the development of reason, as well as the development of the individual etc. In 1881, he wrote:

The eulogists of work. Behind the glorification of 'work' and the tireless talk of the 'blessings of work' I find the same thought as behind the praise of impersonal activity for the public benefit: the fear of everything individual. At bottom, one now feels when confronted with work—and what is invariably meant is relentless industry from early till late—that such work is the best police, that it keeps everybody in harness and powerfully obstructs the development of reason, of covetousness, of the desire for independence. For it uses up a tremendous amount of nervous energy and takes it away from reflection, brooding, dreaming, worry, love, and hatred; it always sets a small goal before one's eyes and permits easy and regular satisfactions. In that way a society in which the members continually work hard will have more security: and security is now adored as the supreme goddess.[24]

The American architect, philosopher, designer, and futurist Buckminster Fuller presented a similar argument which rejected the notion that people should be de facto forced to sell their labor in order to have the right to a decent life.[25][26]

Contemporary era

[edit]Particularly in anarchist circles,[27] some believe that work has become highly alienated throughout history and is fundamentally unhappy and burdensome, and therefore should not be enforced by economic or political means.[28] In this context, some call for the introduction of an unconditional basic income[29] and/or a shorter working week, such as the 4-day workweek.[30] The anarchist/situationist writer Bob Black wrote a well-regarded manifesto in 1985, The Abolition of Work.

Media

[edit]The Idler is a twice-monthly British magazine dedicated to the ethos of "idleness." It was founded in 1993 by Tom Hodgkinson and Gavin Pretor-Pinney with the intention of exploring alternative ways of working and living.[31]

The largest organized anti-work community on the Internet is the subreddit r/antiwork on Reddit[32] with (as of November 2023) over 2.8 million members,[33] who call themselves "idlers" and call for "Unemployment for all, not just the rich!".[34]

In art

[edit]The Swedish Public Freedom Service is a conceptual art project which has been running since 2014, promoting an anti-work message.[35] One of the artists involved argued in relationship to the project that "changes in the last 200 years or so have always been shifts in power, while not much that is fundamental to the construction of society has changed. We are largely marinated in the belief that wage labour must be central."[36]

See also

[edit]- Criticism of capitalism

- Critique of political economy

- Job strain

- Post-work society

- Refusal of work

- Tang ping ("lying flat")

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g Lafargue, Paul (2018). The right to be lazy : and other studies. Franklin Classics Trade Press. ISBN 978-0-344-05949-0. OCLC 1107666777.

- ^ a b c https://libcom.org/files/Bertrand%20Russell%20-%20In%20Praise%20of%20Idleness.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ a b Frayne, David (2011). Critical Social Theory and the Will to Happiness: A Study of Anti-Work Subjectivities. School of Social Sciences Cardiff University. p. 177.

Thinkers such as André Gorz, Bertrand Russell, Herbert Marcuse, and even Marx, in his later writings, have argued for the expansion of a realm of freedom beyond the necessities of labour, in which individuals have more liberty to transcend biological and economic imperatives and be 'free for the world and its culture'

- ^ "Meningslösheten breder ut sig". flamman.se (in Swedish). Retrieved 2022-02-10.

- ^ Patrick, Ruth (2012-03-30). "Work as the primary 'duty' of the responsible citizen: a critique of this work-centric approach". People, Place and Policy Online. 6 (1): 5–15. doi:10.3351/ppp.0006.0001.0002.

- ^ Weeks, Kathi (2011). The Problem with Work Feminism, Marxism, Antiwork Politics, and Postwork Imaginaries. Duke University Press. p. 153.

[...]it was the successes of the proletarian struggle for shorter hours that provoked capital to mechanize production[...]

- ^ Nässén, Jonas (2012-03-30). "Would shorter working time reduce greenhouse gas emissions? An analysis of time use and consumption in Swedish households". Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy. 33 (4): 726–745. doi:10.1068/c12239. S2CID 153675794.

- ^ "Post-work: the radical idea of a world without jobs". The Guardian. 2018-01-19. Retrieved 2022-03-11.

Unsurprisingly, work is increasingly regarded as bad for your health: "Stress … an overwhelming 'to-do' list … [and] long hours sitting at a desk," the Cass Business School professor Peter Fleming notes in his new book, The Death of Homo Economicus, are beginning to be seen by medical authorities as akin to smoking.

- ^ Frayne, David (2011). Critical Social Theory and the Will to Happiness: A Study of Anti-Work Subjectivities. School of Social Sciences Cardiff University. p. 177.

Gorz, for example, pointed to the irrationality of a society that strives for full-employment in spite of having developed the technological means to conquer scarcity.

- ^ a b c d e f g Cross. G. social research,Vol 72:No 2: Summer 2005

- ^ a b c Foster, John Bellamy (2017-09-01). "The Meaning of Work in a Sustainable Society". Monthly Review. 69 (4): 1. doi:10.14452/MR-069-04-2017-08_1. ISSN 0027-0520.

[...] Italian cultural theorist Adriano Tilgher famously declared in 1929: "To the Greeks work was a curse and nothing else," supporting his claim with quotations from Socrates, Plato, Xenophon, Aristotle, Cicero, and other figures, together representing the aristocratic perspective in antiquity.4

- ^ Lafargue, Paul (2017). Rätten till lättja (in Swedish). Bakhåll. p. 63. ISBN 9789177424727.

Antikens filosofer trädde måhända om idéernas ursprung, men de stod enade i sin avsky för arbetet. English: "The ancient philosophers had their disputes upon the origin of ideas, but they agreed when it came to the abhorrence of work."

- ^ Frayne, David (2011). Critical Social Theory and the Will to Happiness: A Study of Anti-Work Subjectivities. School of Social Sciences Cardiff University. p. 177.

- ^ Graeber, David (2019). Bullshit jobs : a theory. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-198347-9. OCLC 1089773163.

- ^ "5 tecken på att du har ett poänglöst "bullshit-jobb"". Chef (in Swedish). 21 November 2018. Retrieved 2022-02-09.

"Struntjobb är jobb vars existens inte kan rättfärdigas ens av dem som utför dem. I stället måste de låtsas att jobbet har någon sorts mening. Detta är strunt-faktorn. Många förväxlar struntjobb med skitjobb, men det är inte alls samma sak. Dåliga jobb är dåliga för att de är tunga eller innebär hemsk arbetsmiljö eller för att lönen suger, men många av de jobben behövs verkligen. Faktum är att ju nyttigare ett jobb är för vårt samhälle, desto lägre är ofta lönen. Medan struntjobben å sin sida ofta är högt respekterade och välbetalda men fullständigt poänglösa. Och människorna som utför dem vet om det", säger David Graeber till amerikanska nättidningen Vox.

- ^ "'I had to guard an empty room': the rise of the pointless job". The Guardian. 2018-05-04. Retrieved 2022-02-09.

- ^ a b c Lordon, Frédéric (2014). Willing Slaves of Capital: Spinoza and Marx on Desire. London: Verso. ISBN 978-1781681602.

- ^ Berardi, Franco (2009). The Soul at Work: From Alienation to Autonomy. Semiotext(e). ISBN 978-1584350767.

- ^ a b Alliger, George (2022). Anti-Work: Psychological Investigations into Its Truths, Problems, and Solution. New York and London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0367758592.

- ^ Debord, Guy (2002). The Society of the Spectacle. Black & Red. ISBN 978-0934868075.

- ^ a b Debord, Debord. Society of the spectacle. Zone books.

- ^ https://ia800506.us.archive.org/11/items/zinelibrary-torrent/ImbecilesGuide.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ "Never Work by Guy Debord 1963". www.marxists.org. Retrieved 2022-03-01.

- ^ Friedrich Nietzsche, The Dawn of Day, p. 173

- ^ "The New York Magazine Environmental Teach-In". New York: 30. 1970.

- ^ Graeber, David (2018). Bullshit jobs : a theory. London: Penguin. pp. 238–239. ISBN 978-0-241-26388-4. OCLC 1037154843.

- ^ Ford, Nick. "7 Key Concepts for Understanding Anti-Work Theory". Films For Action. Retrieved 2022-08-09.

- ^ Peters, Adele (2015-02-02). "Work Is Bullshit: The Argument For "Antiwork"". Fast Company. Retrieved 2022-08-09.

- ^ "A Universal Basic Income Is Anti-Work". The Daily Signal. 2016-02-26. Retrieved 2022-08-09.

- ^ Lashbrooke, Barnaby. "The 'Anti-Work' Movement Is A Sign Something's Rotten In The Workplace". Forbes. Retrieved 2022-08-09.

- ^ "About". Idler. 2014-08-22. Retrieved 2022-08-09.

- ^ Schofield, Daisy (2021-02-15). "Inside the Reddit community calling for the abolition of work". Huck Magazine. Retrieved 2022-08-09.

- ^ "Inside the Online Movement to End Work". www.vice.com. 22 December 2021. Retrieved 2022-08-09.

- ^ "r/antiwork". reddit. Retrieved 2022-08-09.

- ^ "Handelsnytt testar förmedlingen för frihet – Handelsnytt" (in Swedish). 15 April 2019. Retrieved 2022-02-08.

- ^ "Frihetsförmedlingen". issuu. Retrieved 2022-02-08.

Further reading

[edit]- Berardi, Franco. (2009). The soul at work: from alienation to autonomy. Los Angeles, CA: Semiotext(e

- Danaher, John (2019). Automation and utopia: human flourishing in a world without work. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press

- Frayne, David (2015). The refusal of work: the theory and practice of resistance to work. London: Zed Books

- Jonas Nässén, Jörgen Larsson (2015). Would shorter working time reduce greenhouse gas emissions? An analysis of time use and consumption in Swedish households doi:10.1068/c12239[permanent dead link]

- Lafargue, Paul (2011). The right to be lazy: [essays] by Paul Lafargue. Oakland, CA: C. H. Kerr & Co. & AK Press

- Paulsen, Roland (2014). Empty labor: idleness and workplace resistance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- Russell, Bertrand (2004). In praise of idleness and other essays. New ed. London: Routledge

- Seyferth, Peter (2019). "Anti-work: A Stab in the Heart of Capitalism". In Kinna, Ruth; Gordon, Uri (eds.). Routledge Handbook of Radical Politics. New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. pp. 374–390. ISBN 978-1-138-66542-2.

- Susskind, Daniel (2020). A world without work: technology, automation, and how we should respond. London: Allen Lane

- Weeks, Kathi (2011). The problem with work: feminism, Marxism, antiwork politics, and postwork imaginaries. Durham: Duke University Press