Northeast Corridor

The Northeast Corridor (NEC) is an electrified railroad line in the Northeast megalopolis of the United States. Owned primarily by Amtrak, it runs from Boston in the north to Washington, D.C., in the south, with major stops in Providence, New Haven, Stamford, New York City, Newark, Trenton, Philadelphia, Wilmington, and Baltimore. The NEC is roughly paralleled by Interstate 95 for most of its length. Carrying more than 2,200 trains a day,[2] it is the busiest passenger rail line in the United States by ridership and service frequency.[3]

The corridor is used by many Amtrak trains, including the high-speed Acela (formerly Acela Express), intercity trains, and several long-distance trains. Most of the corridor also has frequent commuter rail service, operated by the MBTA, CT Rail, Metro-North Railroad, Long Island Rail Road, New Jersey Transit, SEPTA, and MARC. While large through freights have not run on the NEC since the early 1980s, some sections still carry smaller local freights operated by CSX, Norfolk Southern, CSAO, Providence and Worcester, New York and Atlantic, and Canadian Pacific. CSX and NS partly own their routes.

Long-distance Amtrak services that use the Northeast Corridor include the Cardinal, Crescent, and Silver Meteor trains, which reach 125 mph (201 km/h), as well as its Acela trains, which reach 150 mph (240 km/h) in parts of Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and New Jersey. Some express trains operated by MARC that reach 125 mph (201 km/h) also operate on the Northeast Corridor. Acela can travel the 225 mi (362 km) between New York City and Washington, D.C., in under three hours, and the 229 mi (369 km) between New York and Boston in under 3.5 hours.[4][5]

In 2012, Amtrak proposed improvements to enable "true" high-speed rail on the corridor, which would have roughly halved travel times at an estimated cost of $151 billion.[6][7]

History

[edit]Origins

[edit]Most of what is now called the Northeast Corridor was built, piece by piece, by several railroads constructed as early as the 1830s. Before 1900, their routes had been consolidated as two long and unconnected stretches, each a part of a major railroad. Anchored in Washington, D.C., the stretch owned by the Pennsylvania Railroad, approached New York City from the south, anchored at Boston, the stretch owned by the New Haven Railroad, and entered New York State from Connecticut. The former terminated at New Jersey ferry slips across the Hudson River from Manhattan Island.[8] The latter extended to the Bronx, where it continued into Manhattan via trackage rights on the New York and Harlem Railroad. It also reached the Bronx via the Harlem River and Port Chester Railroad, which extended to the Bronx from the New Haven at New Rochelle.[9]

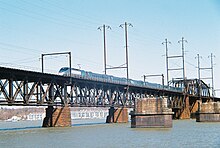

From 1903 to 1917, the two railroads undertook a number of projects that connected their lines and completed, in effect, the Northeast Corridor. These included the New York Tunnel Extension, which extended from New Jersey to Long Island (and was composed of the Manhattan Transfer station, the North River Tunnels, a new Pennsylvania Station, the East River Tunnels), the New York Connecting Railroad, and the Hell Gate Bridge. Combined, these constituted a stretch that started just outside of Newark, New Jersey, on the Pennsylvania Railroad side, and connected with the Harlem River and Port Chester Railroad (and thus New Rochelle) on the New Haven side. With the opening of the Hell Gate Bridge in 1917, this final connecting stretch, and thus the Northeast Corridor itself, was complete.[citation needed]

With the 1968 creation of Penn Central, which was a combination of those two railroads and the New York Central Railroad, the entire corridor was under the control of a single entity for the first time. After successor Penn Central’s 1970 bankruptcy, the corridor was almost entirely subsumed by the subsequently-created Amtrak on May 1, 1971.[citation needed]

Boston–The Bronx (New Haven Railroad)

[edit]- Boston–Providence: Boston and Providence Railroad opened 1835, partially realigned in 1847 and in 1899. Became part of the Old Colony Railroad in 1888.[10]

- Providence–Stonington: New York, Providence and Boston Railroad opened 1837; partially realigned 1848.[citation needed]

- Stonington–New Haven: New Haven, New London and Stonington Railroad opened 1852–1889, realigned in New Haven, 1894.[citation needed]

- New Haven–New Rochelle: New York and New Haven Railroad opened 1849.[citation needed]

- New Rochelle–Port Morris (Bronx): Harlem River and Port Chester Railroad opened 1873.[citation needed]

Newark–Washington, D.C. (Pennsylvania Railroad)

[edit]- Newark–Trenton: United New Jersey Railroad and Canal Company opened 1834–1839, 1841; partially realigned 1863 and 1870.[citation needed]

- Trenton–Frankford Junction: Philadelphia and Trenton Railroad opened 1834; partially realigned 1911.[citation needed]

- Frankford Junction–Zoo Tower: Connecting Railway opened 1867.[citation needed]

- Zoo Tower–Grays Ferry Bridge: Junction Railroad opened 1863–1866.[citation needed]

- Grays Ferry–Bayview: Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad opened 1837–1838,[11] 1866, 1906.[citation needed]

- Bayview Yard–Baltimore Union Station: Union Railroad opened 1873.[12]

- Baltimore Union Station–Landover: Baltimore and Potomac Rail Road opened 1872.[13]

- Landover–Washington, D.C.: Magruder Branch opened 1907[14]

New York City area

[edit]

- The Manhattan Transfer station (just above Newark), opened 1910[15]

- New York Tunnel Extension, opened 1910[15]

- Pennsylvania Station (1910–1963), completed 1910[15]

- New York Connecting Railroad, completed 1917[16]

- Hell Gate Bridge (connected to Harlem River and Port Chester Railroad), opened 1917[16]

Electrification, 1905–38

[edit]New York section

[edit]In 1899, William J. Wilgus, the New York Central Railroad (NYC)'s chief engineer, proposed electrifying the lines leading from Grand Central Terminal and the split at Mott Haven, using a third rail power system devised by Frank J. Sprague. Electricity was in use on some branch lines of the NYNH&H for interurban streetcars via third rail or trolley wire.[17] An accident in the Park Avenue Tunnel near the present Grand Central Terminal that killed 17 people on January 8, 1902, was blamed on smoke from steam locomotives; the resulting outcry led to a push for electric operation in Manhattan.[18][19][20]

The NH announced in 1905 that it would electrify its main line from New York to Stamford, Connecticut.[citation needed] Along with the construction of Grand Central Terminal, which was opened in 1913, the NYC electrified its lines. On September 30, 1906, the NYC conducted a test of suburban multiple unit service to Highbridge station on the Hudson Line;[21]: 97 [22] regular service began on December 11.[23][24] Electric locomotives began serving Grand Central on February 15, 1907,[21]: 115 and all NYC passenger service into Grand Central was electrified on July 1, 1907.[24][25] NH electrification began in July to New Rochelle, August to Port Chester and October the rest of the way to Stamford.[26] Steam trains last operated into Grand Central on June 30, 1908: the deadline after which steam trains were banned in Manhattan.[21]: 55–56 Subsequently, all NH passenger trains into Manhattan were electrified. In June 1914, the NH electrification was extended to New Haven, which was the terminus of electrified service for over 80 years.[27]

The PRR was building its Pennsylvania Station and electrified approaches, which were served by the PRR's lines in New Jersey and the Long Island Rail Road (LIRR). LIRR electric service began in 1905 on the Atlantic Branch from downtown Brooklyn past Jamaica,[28][29] and in June 1910 on the branch to Long Island City: part of the main line to Penn Station.[29] Penn Station opened on September 8, 1910, for LIRR trains[30] and November 27 for the PRR;[31] trains of both railroads were powered by DC electricity from a third rail. PRR trains changed engines (electric to/from steam) at Manhattan Transfer; passengers could also transfer there to H&M trains to downtown Manhattan.[citation needed]

On July 29, 1911, NH began electric service on its Harlem River Branch: a suburban branch that would become a main line with the completion of the New York Connecting Railroad and its Hell Gate Bridge.[32][33] The bridge opened on March 9, 1917,[16] but was operated by steam with an engine change at Sunnyside Yard east of Penn Station until 1918.[citation needed]

Electrification north of New Haven to Providence and Boston had been planned by the NH, and authorized by the company's board of directors shortly before the United States entered World War I. This plan was not carried out because of the war and the company's financial problems. Electrification north of New Haven did not occur until the 1990s, by Amtrak, using a 60 Hz system.

New York to Washington electrification

[edit]

In 1905, the PRR began to electrify its suburban lines at Philadelphia: an effort that eventually led to 11 kV, 25 Hz AC catenary from New York and Washington.[34] Electric service began in September 1915, with multiple unit trains west to Paoli on the PRR Main Line (now the Keystone Corridor).[35] Electric service to Chestnut Hill (now the Chestnut Hill West Line), including a stretch of the NEC, began on March 30, 1918.[citation needed] Local electric service to Wilmington, Delaware, on the NEC began on September 30, 1928, and to Trenton, New Jersey, on June 29, 1930.[citation needed]

Electrified service between Exchange Place, the Jersey City terminal, and New Brunswick, New Jersey, began on December 8, 1932, including the extension of Penn Station electric service from Manhattan Transfer.[citation needed] On January 16, 1933, the rest of the electrification between New Brunswick and Trenton opened, giving a fully-electrified line between New York and Wilmington. Trains to Washington began running under electricity to Wilmington on February 12, 1933, with the engine-change moved from Manhattan Transfer to Wilmington.[citation needed] The same was done on April 9, 1933, for trains running west from Philadelphia, with the change point moved to Paoli.[citation needed]

In 1933, the electrification south of Wilmington was stalled by the Great Depression, but the PRR got a loan from the Public Works Administration to resume work.[36] The tunnels at Baltimore were rebuilt as part of the project. Electric service between New York and Washington began on February 10, 1935.[37] On April 7, the electrification of passenger trains was complete, with 639 daily trains: 191 hauled by locomotives and the other 448 under multiple-unit power.[citation needed] New York–Washington electric freight service began on May 20, 1935, after the electrification of freight lines in New Jersey and Washington,DC. [citation needed] Extensions to Potomac Yard across the Potomac River from Washington, as well as several freight branches along the way, were electrified in 1937 and 1938.[citation needed] The Potomac Yard retained its electrification until 1981.[citation needed]

Re-signaling

[edit]In the 1930s, PRR equipped the New York–Washington line with Pulse code cab signaling. Between 1998 and 2003, this system was overlaid with an Alstom Advanced Civil Speed Enforcement System (ACSES), using track-mounted transponders similar to the Balises of the modern European Train Control System.[38] The ACSES will enable Amtrak to implement positive train control to comply with the Rail Safety Improvement Act of 2008.[citation needed]

Founding and operation of Amtrak

[edit]Reorganization and bankruptcy

[edit]

In December 1967, the UAC TurboTrain set a speed record for a production train: 170.8 miles per hour (274.9 km/h) between New Brunswick and Trenton, New Jersey.[39]

In February 1968, PRR merged with its rival New York Central Railroad to form the Penn Central (PC).[40] Penn Central was required to absorb the New Haven in 1969 as a condition of the merger.[41]

On September 21, 1970, all New York–Boston trains except the Turboservice were rerouted into Penn Station from Grand Central;[citation needed] the Turboservice moved on February 1, 1971, for cross-platform transfers to the Metroliners.[42]

In 1971, Amtrak began operations, and various state governments took control of portions of the NEC for their commuter transportation authorities. In January, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts bought the Attleboro/Stoughton Line in Massachusetts,[citation needed] later operated by the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. The same month, the New York State Metropolitan Transportation Authority bought, and Connecticut leased, from Penn Central their sections of the New Haven Line, between Woodlawn, New York, and New Haven, Connecticut.[42]

In 1973, the Regional Rail Reorganization Act opened the way for Amtrak to buy sections of the NEC not already been sold to these commuter transportation authorities. These purchases by Amtrak were controversial at the time, and the Department of Transportation blocked the transaction and withheld purchase funds for several months until Amtrak granted it control over reconstruction of the corridor.[43]

In February 1975, the Preliminary System Plan for Conrail proposed to stop running freight trains on the NEC between Groton, Connecticut, and Hillsgrove, Rhode Island, but this clause was rejected the following month by the U.S. Railway Association.[44]

By April 1976, Amtrak owned the entire NEC except Boston to the RI state line, which is owned by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, and New Haven to New Rochelle, New York, which is owned by the States of Connecticut and New York. Amtrak still operates and maintains the portion in Massachusetts, but the line from New Haven to New Rochelle, New York, is operated by the Metro-North Railroad, which has hindered the establishment of high-speed service.[45][46]

Northeast Corridor Improvement Project

[edit]

In 1976, Congress authorized an overhaul of the system between Washington and Boston.[47] Called the Northeast Corridor Improvement Project (NECIP), it included safety improvements, modernization of the signaling system by General Railway Signal, and new Centralized Electrification and Traffic Control (CETC) control centers by Chrysler at Philadelphia, New York and Boston.[citation needed] It allowed more trains to run faster and closer together, and set the stage for later high-speed operation. NECIP also introduced the AEM-7 locomotive, which lowered travel times and became the most successful engine on the Corridor. The NECIP set travel time goals of 2 hours and 40 minutes between Washington and New York, and 3 hours and 40 minutes between Boston and New York.[48] These goals were not met because of the low level of funding provided by the Reagan Administration and Congress in the 1980s.[49]

Electrification between New Haven and Boston was to be included in the 1976 Railroad Revitalization and Regulatory Reform Act.[47]

The last grade crossings between New York and Washington were closed about 1985; eleven grade crossings remain in Connecticut.

1990s implementation of high-speed rail

[edit]

In the 1990s, Amtrak upgraded the NEC north of New Haven, CT to get it ready for the high-speed Acela Express trains.[49] Dubbed the Northeast High Speed Rail Improvement Program (NHRIP), the effort eliminated grade crossings, rebuilt bridges and modified curves. Concrete railroad ties replaced wood ties, and heavier continuous welded rail (CWR) was laid-down.[50]

In 1996, Amtrak began installing electrification gear along the 157 miles (253 kilometres) of track between New Haven and Boston. The infrastructure included a new overhead catenary wire made of high-strength silver-bearing copper, specified by Amtrak and later patented by Phelps Dodge Specialty Copper Products of Elizabeth, New Jersey.[51]

2000–present

[edit]

Service with electric locomotives between New Haven and Boston began on January 31, 2000.[52] The project took four years and cost close to $2.3 billion: $1.3 billion for the infrastructure improvements and close to $1 billion for both the new Acela Express trainsets and the Bombardier–Alstom HHP-8 locomotives.[53]

On December 11, 2000, Amtrak began operating its higher-speed Acela Express service.[54] Fastest travel time by Acela is three and a half hours between Boston and New York, and two hours forty-five minutes between New York and Washington, D.C.[55]

In 2005, there was talk in Congress of splitting the Northeast Corridor, which was opposed by then-acting Amtrak president David Gunn. The plan, supported by the Bush administration, would "turn over the Northeast Corridor – the tracks from Washington to Boston that are the railroad's main physical asset – to a federal-state consortium."[56]

With the passage of the Passenger Rail Investment and Improvement Act of 2008, the Congress established the Northeast Corridor Commission (NEC Commission) in the U.S. Department of Transportation to facilitate mutual cooperation and planning and to advise Congress on Corridor rail and development policy. The commission members include USDOT, Amtrak and the Northeast Corridor states.

In October 2010, Amtrak released "A Vision for High-Speed Rail on the Northeast Corridor," an aspirational proposal for dedicated high-speed rail tracks between Washington, D.C., and Boston.[57] Many of these proposals are unfunded.

In August 2011 the United States Department of Transportation committed $450 million to a six-year project to support capacity increases on one of the busiest segments on the NEC: a 24-mile (39 km) section between New Brunswick and Trenton, passing through Princeton Junction. The Next Generation High-Speed project is designed to upgrade electrical power, signal systems and overhead catenary wires to improve reliability and increase speeds up to 160 mph (260 km/h), and, after the purchase of new equipment, up to 186 miles per hour (299 km/h).[58] In September 2012, speed tests were conducted using Acela trainsets, achieving a speed of 165 miles per hour (266 km/h).[59][60] The improvements were scheduled to be completed in 2016, but, due to delays, the project had not been completed until 2020.[61][62]

In 2012, the Federal Railroad Administration began developing a master plan for bringing high-speed rail to the Northeast Corridor titled NEC FUTURE, and released the final environmental impact statement in December 2016.[63] Multiple potential alignments north of New York City were studied.[64] The proposed upgrades have not been funded.

2015 derailment

[edit]

Eleven minutes after leaving 30th Street Station in Philadelphia on May 12, 2015, a year-old ACS-64 locomotive (#601) and all seven Amfleet I coaches of Amtrak's northbound Northeast Regional (TR#188) derailed at 9:21pm at Frankford Junction in the Port Richmond section of the city, while entering a 50 mph (80 km/h) speed limited (but at the time non-ATC protected) 4° curve at 106 mph (171 km/h), killing eight and injuring more than 200 (eight critically) of the 238 passengers and five crew on board as well as causing the suspension of all Philadelphia–New York NEC service for six days.[65][66]

This was the deadliest crash on the Northeast Corridor since 16 died when Amtrak's Washington–Boston Colonial (TR#94) rear-ended three stationary Conrail locomotives at Gunpow Interlocking near Baltimore on January 4, 1987.[67] Frankford Junction curve was the site of a previous fatal accident on September 6, 1943, when an extra section of the PRR's Washington to New York Congressional Limited derailed there, killing 79 and injuring 117 of the 541 on board.[68]

Infrastructure

[edit]The NEC is a cooperative venture between Amtrak and various state agencies. Amtrak owns the track between Washington and New Rochelle, New York, a northern suburb of New York City.[citation needed] The segment from New Rochelle to New Haven is owned by the states of New York and Connecticut; Metro-North Railroad commuter trains operate there.[citation needed] Amtrak owns the tracks north of New Haven to the border between Rhode Island and Massachusetts. The final segment from the border north to Boston is owned by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts.[citation needed]

Electrification

[edit]

At just over 453 miles (729 km), the Northeast Corridor is the longest electrified rail corridor in the United States.[citation needed] Most electrified railways in the country are for rapid transit or commuter rail use; the Keystone Corridor is the only other electrified intercity mainline.[citation needed]

Currently, the corridor uses three catenary systems. From Washington, D.C., to Sunnyside Yard (just east of New York Penn Station), Amtrak's 25 Hz traction power system (originally built by the Pennsylvania Railroad) supplies 12 kV at 25 Hz. From Sunnyside to Mill River (just east of New Haven station), the former New Haven Railroad's system, since modified by Metro-North, supplies 12.5 kV at 60 Hz. From Mill River to Boston, the much newer 60 Hz traction power system supplies 25 kV at 60 Hz. All of Amtrak's electric locomotives can switch between these systems.

In addition to catenary, the East River Tunnels have 750 V DC third rail for Long Island Rail Road trains, and the North River Tunnels have third rail for emergency use only.

In 2006, several high-profile electric-power failures delayed Amtrak and commuter trains on the Northeast Corridor up to five hours.[69] Railroad officials blamed Amtrak's funding woes for the deterioration of the track and power supply system, which in places is almost a hundred years old. These problems have decreased in recent years after tracks and power systems were repaired and improved.[70]

In September 2013, one of two feeder lines supplying power to the New Haven Line failed, while the other feeder was disabled for service. The lack of electrical power disrupted trains on Amtrak and Metro-North Railroad, which share the segment in New York State.[71]

Stations

[edit]

There are 109 active stations on the Northeast Corridor; 30 are used by Amtrak. All but three (Kingston, Westerly, and Mystic) see commuter service. Amtrak owns Pennsylvania Station in New York, 30th Street Station in Philadelphia, Penn Station in Baltimore, and Union Station in Washington.[citation needed]

The main services of the Northeast Corridor are indicated using the following abbreviations. Other services are listed in the right-most column. Note that not all trains necessarily stop at all indicated stations.

- Amtrak corridor: A (Acela), KS (Keystone Service), NR (Northeast Regional), PA (Pennsylvanian), VT (Vermonter)

- Amtrak long distance: CD (Cardinal), CL (Carolinian), CS (Crescent), PL (Palmetto), SM (Silver Meteor)

- MBTA Commuter Rail: P/S (Providence/Stoughton Line), NE (Needham Line), FR (Franklin/Foxboro Line)

- CT Rail: SLE (Shore Line East)

- Metro-North Railroad: NHV (New Haven Line)

- NJ Transit Rail: NEC (Northeast Corridor Line), NJC (North Jersey Coast Line), RV (Raritan Valley Line)

- SEPTA Regional Rail: CHW (Chestnut Hill West Line), NWK (Wilmington/Newark Line), TRE (Trenton Line)

- MARC Train: PEN (Penn Line)

| State | Distance from NYP |

City | Station | Amtrak corridor services |

Amtrak long-distance services | Commuter services |

Additional rail services/connections | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MA | 228.7 mi (368.1 km) | Boston | South Station | A | NR | P/S | NE | FR | |||||||||

| 227.6 mi (366.3 km) | Back Bay | A | NR | P/S | NE | FR | |||||||||||

| 226.5 mi (364.5 km) | Ruggles | P/S | NE | FR | |||||||||||||

| 223.7 mi (360.0 km) | Forest Hills | P/S | NE | FR | |||||||||||||

| 220.6 mi (355.0 km) | Hyde Park | P/S | FR | ||||||||||||||

| 219.2 mi (352.8 km) | Readville | FR | |||||||||||||||

| 217.3 mi (349.7 km) | Westwood | Route 128 | A | NR | P/S | ||||||||||||

| 213.9 mi (344.2 km) | Canton | Canton Junction | P/S | ||||||||||||||

| 210.8 mi (339.2 km) | Sharon | Sharon | P/S | ||||||||||||||

| 204.0 mi (328.3 km) | Mansfield | Mansfield | P/S | ||||||||||||||

| 196.9 mi (316.9 km) | Attleboro | Attleboro | P/S | ||||||||||||||

| 191.9 mi (308.8 km) | South Attleboro | P/S | |||||||||||||||

| RI | 189.3 mi (304.6 km) | Pawtucket | Pawtucket/Central Falls | P/S | |||||||||||||

| 185.1 mi (297.9 km) | Providence | Providence | A | NR | P/S | ||||||||||||

| 177.3 mi (285.3 km) | Warwick | T. F. Green Airport | P/S | ||||||||||||||

| 165.8 mi (266.8 km) | North Kingstown | Wickford Junction | P/S | ||||||||||||||

| 158.1 mi (254.4 km) | West Kingston | Kingston | NR | ||||||||||||||

| 141.3 mi (227.4 km) | Westerly | Westerly | NR | ||||||||||||||

| CT | 132.3 mi (212.9 km) | Mystic | Mystic | NR | |||||||||||||

| 122.9 mi (197.8 km) | New London | New London | NR | SLE | |||||||||||||

| 105.1 mi (169.1 km) | Old Saybrook | Old Saybrook | NR | SLE | |||||||||||||

| 101.2 mi (162.9 km) | Westbrook | Westbrook | SLE | ||||||||||||||

| 96.8 mi (155.8 km) | Clinton | Clinton | SLE | ||||||||||||||

| 93.1 mi (149.8 km) | Madison | Madison | SLE | ||||||||||||||

| 88.8 mi (142.9 km) | Guilford | Guilford | SLE | ||||||||||||||

| 81.4 mi (131.0 km) | Branford | Branford | SLE | ||||||||||||||

| 72.7 mi (117.0 km) | New Haven | New Haven State Street | SLE | NHV | |||||||||||||

| 72.3 mi (116.4 km) | New Haven Union Station | A | NR | VT | SLE | NHV | |||||||||||

| 69.4 mi (111.7 km) | West Haven | West Haven | SLE | NHV | |||||||||||||

| 63.3 mi (101.9 km) | Milford | Milford | SLE | NHV | |||||||||||||

| 59.0 mi (95.0 km) | Stratford | Stratford | SLE | NHV | |||||||||||||

| 55.4 mi (89.2 km) | Bridgeport | Bridgeport | NR | VT | SLE | NHV | |||||||||||

| 52.3 mi (84.2 km) | Fairfield | Fairfield–Black Rock | NHV | ||||||||||||||

| 50.6 mi (81.4 km) | Fairfield | NHV | |||||||||||||||

| 48.9 mi (78.7 km) | Southport | NHV | |||||||||||||||

| 47.2 mi (76.0 km) | Westport | Green's Farms | NHV | ||||||||||||||

| 44.2 mi (71.1 km) | Westport | NHV | |||||||||||||||

| 42.1 mi (67.8 km) | Norwalk | East Norwalk | NHV | ||||||||||||||

| 41.0 mi (66.0 km) | South Norwalk | NHV | |||||||||||||||

| 39.2 mi (63.1 km) | Rowayton | NHV | |||||||||||||||

| 37.7 mi (60.7 km) | Darien | Darien | NHV | ||||||||||||||

| 36.2 mi (58.3 km) | Noroton Heights | NHV | |||||||||||||||

| 33.1 mi (53.3 km) | Stamford | Stamford | A | NR | VT | SLE | NHV | ||||||||||

| 31.3 mi (50.4 km) | Greenwich | Old Greenwich | NHV | ||||||||||||||

| 30.3 mi (48.8 km) | Riverside | NHV | |||||||||||||||

| 29.6 mi (47.6 km) | Cos Cob | NHV | |||||||||||||||

| 28.1 mi (45.2 km) | Greenwich | NHV | |||||||||||||||

| NY | 25.7 mi (41.4 km) | Port Chester | Port Chester | NHV | |||||||||||||

| 24.1 mi (38.8 km) | Rye | Rye | NHV | ||||||||||||||

| 22.2 mi (35.7 km) | Harrison | Harrison | NHV | ||||||||||||||

| 20.5 mi (33.0 km) | Mamaroneck | Mamaroneck | NHV | ||||||||||||||

| 18.7 mi (30.1 km) | Larchmont | Larchmont | NHV | ||||||||||||||

| 16.6 mi (26.7 km) | New Rochelle | New Rochelle | NR | NHV | |||||||||||||

| 0.0 mi (0 km) | New York | Penn Station | A | NR | VT | KS | PA | CD | CL | CS | PL | SM | RARV | NEC | NJCL | ||

| NJ | 5.0 mi (8.0 km) | Secaucus | Secaucus Junction | RARV | NEC | NJCL | |||||||||||

| 10.0 mi (16.1 km) | Newark | Penn Station | A | NR | VT | KS | PA | CD | CL | CS | PL | SM | RARV | NEC | NJCL | ||

| 12.6 mi (20.3 km) | Newark Airport | NR | KS | NEC | NJCL | ||||||||||||

| 14.4 mi (23.2 km) | Elizabeth | North Elizabeth | NEC | NJCL | |||||||||||||

| 15.4 mi (24.8 km) | Elizabeth | NEC | NJCL | ||||||||||||||

| 18.6 mi (29.9 km) | Linden | Linden | NEC | NJCL | |||||||||||||

| 20.7 mi (33.3 km) | Rahway | Rahway | NEC | NJCL | Transfer point between service to Trenton and Long Branch/Bay Head | ||||||||||||

| 24.6 mi (39.6 km) | Woodbridge | Metropark | A | NR | VT | KS | CS | NEC | |||||||||

| 27.1 mi (43.6 km) | Metuchen | Metuchen | NEC | ||||||||||||||

| 30.3 mi (48.8 km) | Edison | Edison | NEC | ||||||||||||||

| 32.7 mi (52.6 km) | New Brunswick | New Brunswick | NR | KS | NEC | ||||||||||||

| 34.4 mi (55.4 km) | Jersey Avenue | NEC | |||||||||||||||

| 48.8 mi (78.5 km) | Princeton Junction | Princeton Junction | NR | KS | NEC | ||||||||||||

| 54.4 mi (87.5 km) | Hamilton Twp. | Hamilton | NEC | ||||||||||||||

| 58.1 mi (93.5 km) | Trenton | Trenton | NR | VT | KS | PA | CD | CL | CS | PL | SM | TRE | NEC | ||||

| PA | 64.7 mi (104.1 km) | Tullytown | Levittown | TRE | |||||||||||||

| 67.8 mi (109.1 km) | Bristol | Bristol | TRE | ||||||||||||||

| 70.7 mi (113.8 km) | Croydon | Croydon | TRE | ||||||||||||||

| 72.4 mi (116.5 km) | Eddington | Eddington | TRE | ||||||||||||||

| 73.7 mi (118.6 km) | Cornwells Heights | Cornwells Heights | KS | TRE | |||||||||||||

| 75.8 mi (122.0 km) | Philadelphia | Torresdale | TRE | ||||||||||||||

| 78.3 mi (126.0 km) | Holmesburg Junction | TRE | |||||||||||||||

| 79.3 mi (127.6 km) | Tacony | TRE | |||||||||||||||

| 81.2 mi (130.7 km) | Bridesburg | TRE | |||||||||||||||

| 86.0 mi (138.4 km) | North Philadelphia | KS | TRE | CHW | |||||||||||||

| 90.5 mi (145.6 km) | 30th Street Station | A | NR | VT | KS | PA | CD | CL | CS | PL | SM | TRE | NWK | CHW | |||

| 94.8 mi (152.6 km) | Darby | Darby | NWK | ||||||||||||||

| 95.5 mi (153.7 km) | Sharon Hill | Curtis Park | NWK | ||||||||||||||

| 96.2 mi (154.8 km) | Sharon Hill | NWK | |||||||||||||||

| 96.7 mi (155.6 km) | Folcroft | Folcroft | NWK | ||||||||||||||

| 97.3 mi (156.6 km) | Glenolden | Glenolden | NWK | ||||||||||||||

| 98.0 mi (157.7 km) | Norwood | Norwood | NWK | ||||||||||||||

| 98.7 mi (158.8 km) | Prospect Park | Prospect Park | NWK | ||||||||||||||

| 99.4 mi (160.0 km) | Ridley Park | Ridley Park | NWK | ||||||||||||||

| 100.1 mi (161.1 km) | Crum Lynne | NWK | |||||||||||||||

| 101.3 mi (163.0 km) | Eddystone | Eddystone | NWK | ||||||||||||||

| 102.4 mi (164.8 km) | Chester | Chester T.C. | NWK | ||||||||||||||

| 104.5 mi (168.2 km) | Highland Avenue | NWK | |||||||||||||||

| 105.7 mi (170.1 km) | Marcus Hook | Marcus Hook | NWK | ||||||||||||||

| DE | 108.6 mi (174.8 km) | Claymont | Claymont | NWK | |||||||||||||

| 115.8 mi (186.4 km) | Wilmington | Wilmington | A | NR | VT | CD | CL | CS | PL | SM | NWK | ||||||

| 121.5 mi (195.5 km) | Churchmans Crossing | NWK | |||||||||||||||

| 127.7 mi (205.5 km) | Newark | Newark | NR | NWK | |||||||||||||

| MD | 148.5 mi (239.0 km) | Perryville | Perryville | PEN | |||||||||||||

| 154.5 mi (248.6 km) | Aberdeen | Aberdeen | NR | PEN | |||||||||||||

| 164.1 mi (264.1 km) | Edgewood | Edgewood | PEN | ||||||||||||||

| 173.0 mi (278.4 km) | Middle River | Martin State Airport | PEN | ||||||||||||||

| 184.7 mi (297.2 km) | Baltimore | Penn Station | A | NR | VT | CD | CL | CS | PL | SM | PEN | ||||||

| 187.5 mi (301.8 km) | West Baltimore | PEN | |||||||||||||||

| 192.3 mi (309.5 km) | Halethorpe | Halethorpe | PEN | ||||||||||||||

| 195.3 mi (314.3 km) | Linthicum Heights | BWI Airport | A | NR | VT | CS | PL | PEN | |||||||||

| 202.6 mi (326.1 km) | Odenton | Odenton | PEN | ||||||||||||||

| 208.4 mi (335.4 km) | Bowie | Bowie State | PEN | ||||||||||||||

| 213.7 mi (343.9 km) | Seabrook | Seabrook | PEN | ||||||||||||||

| 216.0 mi (347.6 km) | New Carrollton | New Carrollton | NR | VT | PL | PEN | |||||||||||

| DC | 224.7 mi (361.6 km) | Washington | Union Station | A | NR | VT | CD | CL | CS | PL | SM | PEN | |||||

Grade crossings

[edit]

The entire Northeast Corridor has 11 grade crossings, all in southeastern New London County, Connecticut. The remaining grade crossings are along a part of the line that hugs the shore of Long Island Sound. Some of these crossings constitute the only points of access to waterfront communities and businesses otherwise disconnected from the road network. As such, eliminating them would require grade separation to maintain access. Six of the grade crossings have four-quadrant gates with induction loop sensors, which allow vehicles stopped on the tracks to be detected in time for an oncoming train to stop. The remaining five grade crossings, 3 near New London Union Station and two in Stonington, have dual gates.[72]

FRA rules limit track speeds on the corridor to 80 miles per hour (130 km/h) over conventional crossings and 95 miles per hour (153 km/h) over crossings with four-quadrant gates and vehicle detection tied into the signal system.[73]

History

[edit]The New York to New Haven line has long been completely grade-separated, and the last grade crossings between Washington and New York were eliminated in the 1980s.[citation needed] In 1994, during planning for electrification and high-speed Acela Express service between New Haven and Boston, a law was passed requiring USDOT to plan for the elimination of all remaining crossings (unless impractical or unnecessary) by 1997.[74] Some lightly used crossings were simply closed, while most were converted into bridges or underpasses. Only thirteen remained by 1999, of which lightly used crossings in Old Lyme, Connecticut, and Exeter, Rhode Island, were soon closed.[75]

Despite six nonfatal accidents in the previous sixteen years, there was substantial local opposition to closing the remaining 11 crossings. Outright closing the crossing would eliminate the sole access points to several of the places they served, while grade separation would be expensive and require land takings.[75] Instead, the crossings were supplied with additional protections. In 1998, School Street in Groton was the first four-quadrant gate installation in the country with vehicle detection sensors tied into the line's signal system.[76] It cost $1 million rather than the $4 million for a bridge.[77] Seven more crossings received similar installations in 1999 and 2000; only the three in New London (which are on a tight curve with speed limits under 30 miles per hour (48 km/h)) did not.[78]

On September 28, 2005, a southbound Acela Express struck a car at Miner Lane in Waterford, Connecticut, the first such incident since the additional protections were implemented.[79] The train was approaching the crossing at approximately 70 miles per hour (110 km/h) when the car reportedly rolled under the lowered crossing gate arms too late for the sensor system to fully stop the train. The driver and one passenger were killed on impact; the other passenger died nine days later from injuries sustained in the crash. The gates were later inspected and declared to have been functioning properly at the time of the incident.[80] The incident drew public criticism about the remaining grade crossings along the busy line.[81]

Crossing list

[edit]Crossing are listed east to west.[72]

| Miles | City | Street | DOT/AAR number | Coordinates | Details |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 140.6 | Stonington | Palmer St. | 500263U | 41°22′21″N 71°50′08″W / 41.372491°N 71.835678°W | Connects the Pawcatuck residential area to the Mechanic Street arterial. |

| 136.7 | Elihu Island Rd. | 500267W | 41°20′27″N 71°53′24″W / 41.340922°N 71.889912°W | Provides sole access to Elihu Island. Private crossing. | |

| 136.6 | Walker's Dock | 500269K | 41°20′24″N 71°53′28″W / 41.340073°N 71.891184°W | Provides sole access to a small marina. Private crossing. | |

| 134.9 | Wamphassuc Rd. | 500272T | 41°20′31″N 71°55′18″W / 41.342016°N 71.921605°W | Provides sole access to a residential area. | |

| 133.4 | Latimer Point Rd. | 500275N | 41°20′29″N 71°56′56″W / 41.341312°N 71.948967°W | Provides sole access to a residential area. | |

| 132.3 | Broadway Ave. Extension | 500277C | 41°21′03″N 71°57′50″W / 41.350813°N 71.963872°W | Next to Mystic station. Provides sole access to a residential and industrial area, several marinas, and the northbound platform. | |

| 131.2 | Groton | School St. | 500278J | 41°20′42″N 71°58′38″W / 41.344933°N 71.977092°W | Provides sole access to the Willow Point residential area and marina. |

| 123.0 | New London | Ferry St. | 500294T | 41°21′25″N 72°05′41″W / 41.356984°N 72.094777°W | Provides sole access to Block Island Ferry and Cross Sound Ferry docks and other marine facilities. Does not have quad gates. |

| 122.8 | State St. | 500295A | 41°21′14″N 72°05′35″W / 41.353845°N 72.092991°W | Next to New London Union Station. Provides access to the Fisher's Island Ferry, City Pier, Waterfront Park, and the northbound platform. | |

| 122.5 | Bank St. Connector | 500297N | 41°21′05″N 72°05′45″W / 41.35128°N 72.095957°W | Provides access to Waterfront Park. | |

| 120.2 | Waterford | Miner Ln. | 500307S | 41°20′09″N 72°07′26″W / 41.335726°N 72.123845°W | Provides sole access to a residential and industrial area. |

Passenger ridership

[edit]| Annual passenger ridership | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FY* | Northeast Regional | Acela | Total ridership | % Change |

| 2004 | 6,475,000 | 2,569,000 | 9,044,000 | |

| 2005 | 7,116,000 | 1,773,000 | 8,889,000 | -1.7% |

| 2006 | 6,755,000 | 2,583,000 | 9,338,000 | +5.1% |

| 2007 | 6,837,000 | 3,184,000 | 10,021,000 | +7.3% |

| 2008 | 7,489,000 | 3,399,000 | 10,888,000 | +8.7% |

| 2009 | 6,921,000 | 3,020,000 | 9,941,000 | -8.7% |

| 2011 | 7,515,000 | 3,379,000 | 10,894,000 | +5.1% |

| 2012 | 8,014,000 | 3,395,000 | 11,409,000 | +4.7% |

| 2013 | 8,044,000 | 3,343,000 | 11,387,000 | -0.2% |

| 2014 | 8,083,000 | 3,545,000 | 11,628,000 | +2.2% |

| 2015 | 8,215,523 | 3,473,644 | 11,707,079 | +0.7% |

| 2016 | 8,409,662 | 3,489,311 | 11,909,847 | +1.7% |

| 2017 | 8,569,867 | 3,442,188 | 12,027,305 | +1.0% |

| 2018 | 8,686,930 | 3,428,338 | 12,123,643 | +0.8% |

| 2019 | 8,940,745 | 3,577,455 | 12,525,602 | +3.3% |

| 2020 | 4,486,837 | 1,656,764 | 6,147,481 | -49.7% |

| 2021 | 3,508,766 | 897,639 | 4,408,825 | |

| 2022 | 7,091,325 | 2,144,369 | 9,235,694 | +109.5% |

| 2023 | 9,163,082 | 2,959,384 | 12,122,466 | +31.3% |

| Sources: 2004–2014;[82] 2015–2016[83]

2017–2018[84] 2018–2019[85] 2019–2020[86]2019-2021[87]2021-2022[88]2023[89] | ||||

Current rail service

[edit]Intercity passenger services

[edit]

In 2003, Amtrak accounted for about 14% of intercity trips between the cities served by the NEC and its branches (the rest were taken by airline, automobile, or bus).[90] A 2011 study estimated that in 2010 Amtrak carried 6% of the Boston–Washington traffic, compared to 80% for automobiles, 8–9% for intercity bus, and 5% for airlines.[91] Amtrak's share of the air or rail passenger traffic between New York City and Boston has grown from 20 percent to 54 percent since 2001, and 75 percent between New York City and Washington, D.C.[92]

These Amtrak trains serve NEC stations and run at least partially on the corridor:

- Acela: high-speed rail Boston–Washington, D.C.

- Cardinal: New York–Chicago via Washington, D.C. (Wednesdays, Fridays, & Sundays only)

- Carolinian: New York–Charlotte, North Carolina

- Crescent: New York–New Orleans

- Keystone Service: higher-speed rail Harrisburg, Pennsylvania – New York

- Northeast Regional: higher-speed rail (This service qualifies as high speed rail on the 125mph stretch between New Brunswick and Princeton Junction.) Boston/Springfield/New York–Washington D.C./Richmond/Newport News/Norfolk/Roanoke, Virginia

- Palmetto: Savannah, Georgia – New York

- Pennsylvanian: Pittsburgh–New York via NEC and Philadelphia to Harrisburg Main Line

- Silver Meteor: Miami–New York

- Vermonter: St. Albans, Vermont – Washington, D.C., via NEC and New Haven–Springfield Line

Eight other Amtrak trains terminate at NEC stations, but do not use any NEC infrastructure outside the terminus:

- Amtrak Hartford Line: operated in conjunction with ConnDOT, runs across Amtrak-owned New Haven–Springfield line from Springfield Union to New Haven Union, the latter of which uses NEC infrastructure.

- Capitol Limited: runs from Washington, D.C. Union to Chicago Union, the former of which uses NEC infrastructure.

Six Amtrak services operate via the Empire Corridor, a line largely owned by CSX, with other sections owned by Metro-North Railroad and Amtrak. It meets the NEC at New York Penn Station.

- Adirondack: runs from New York Penn to Montreal Central

- Berkshire Flyer: higher-speed rail from New York Penn to Albany–Rensselaer and the Joseph Scelsi Intermodal Transportation Center in Pittsfield, Massachusetts

- Empire Service: higher-speed rail from New York Penn to Albany–Rensselaer and Niagara Falls

- Ethan Allen Express: runs from Burlington Union to New York Penn

- Lake Shore Limited: runs from Chicago Union to New York Penn; also has a branch to the NEC's terminus at Boston South

- Maple Leaf: runs from New York Penn to Toronto Union

Due to the wide availability of the Northeast Regional, Keystone Service, and Acela, as well as commuter rail, most long- and medium-haul trains operating along the New York-Washington leg of the NEC do not allow local travel between NEC stations. In most cases, long- and medium-haul trains only stop to discharge passengers from Washington (and in some cases, Alexandria) northward, and to receive passengers from Newark to Washington. This policy is intended to keep seats available for passengers making longer trips. The Vermonter and Palmetto are the only medium- and long-haul trains that allow local travel in both directions between New York and Washington. The southbound Carolinian allows local travel daily, while the northbound Carolinian only allows local travel on Sundays, Thursdays, and Fridays. Additionally, the medium-haul Pennsylvanian allows local NEC travel, but this train leaves the corridor in Philadelphia and does not travel all the way to Washington.

Commuter rail

[edit]

In addition to Amtrak, several commuter rail agencies operate passenger service using the NEC tracks:

- Providence/Stoughton Line: Wickford Junction–Boston

- Franklin/Foxboro Line: Readville–Boston

- Needham Line: Forest Hills–Boston

- Framingham/Worcester Line: Back Bay Station–Boston

The only section north of New York that does not have commuter service is the 43 miles between Wickford Junction and New London.

- Hartford Line: New Haven Union Station–New Haven-State Street

- Shore Line East: Stamford–New London, Connecticut

Metro-North Railroad (MNRR)

[edit]- New Haven Line: New Rochelle, New York–New Haven, Connecticut

- Danbury Branch: Stamford–Norwalk, Connecticut

- Waterbury Branch: Bridgeport–Stratford, Connecticut

Long Island Rail Road (LIRR)

[edit]- City Terminal Zone: Sunnyside Yard, Queens–New York

New Jersey Transit (NJT)

[edit]

- Northeast Corridor Line: Trenton, NJ–New York

- North Jersey Coast Line: Rahway, NJ–New York

- Morristown Line, Gladstone Branch, Montclair-Boonton Line: Kearny Connection–New York

- Raritan Valley Line: Hunter Connection–New York

- Atlantic City Line: 30th Street Station–Frankford Junction

- Trenton Line: Philadelphia–Trenton, New Jersey

- Airport Line: 30th Street Station–Southwest Philadelphia

- Media/Wawa Line: 30th Street Station–Arsenal Junction

- Chestnut Hill West Line: 30th Street Station–North Philadelphia Station

- Wilmington/Newark Line: Newark, Delaware–Philadelphia

- Penn Line: Washington, D.C.–Perryville, Maryland, via Baltimore Penn Station

Freight services

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2022) |

Freight trains operate on parts of the NEC through trackage rights. Prior to the 1970s when Amtrak took over all passenger service, the NEC routinely saw lengthy freight trains sometimes numbering over one hundred cars traversing great lengths of the corridor. All freight operations ultimately came under the control of Penn Central in the late 1960s and later Conrail upon its formation in 1976, however Amtrak, whose ridership was steadily increasing began demanding heavier taxes for longer trains. Ultimately Conrail began reducing freight service to only small, local trains on certain sections of the corridor where most needed once longer freights began causing congestion and bigger delays with passenger service.

Currently, Norfolk Southern Railway operates over the line south of Philadelphia. CSX Transportation has rights from New York to New Haven; in Massachusetts; and in Maryland from Landover, where its Landover Subdivision joins the NEC, to Bowie, where its Pope's Creek Subdivision leaves it. Between Philadelphia and New York, Conrail Shared Assets Operations operates as a local switching and terminal company for CSX and Norfolk Southern. The Providence and Worcester Railroad operates local freight service from New Haven into Rhode Island and has overhead trackage rights from New Haven to New York over the Hell Gate Bridge to Fresh Pond Junction.[93] Additionally, the Canadian Pacific Kansas City and the New York and Atlantic Railway both have trackage rights over the Hell Gate Bridge in order to connect with their own routes near New York.[94]

Future NEC projects

[edit]Gateway Program

[edit]In February 2011, Amtrak announced plans for the Gateway Project between Newark Penn Station and New York Penn Station.[95] The planned project would create a high-speed alignment across the New Jersey Meadowlands and under the Hudson River, including the replacement of the Portal Bridge, a bottleneck.

Harold Interlocking

[edit]In May 2011, a $294.7-million federal grant was awarded to fix congestion at Harold Interlocking, the USA's second-busiest rail junction after Sunnyside Yard. The work will lay tracks to the New York Connecting Railroad right of way, allowing Amtrak trains arriving from or bound for New England to avoid NJ Transit and Long Island Rail Road trains.[96][97] Financing for the project was jeopardized in July 2011 by the House of Representatives, which voted to divert the funding to unrelated projects.[98] The project was then funded by FRA and the MTA.[99] As of 2018[update], the interlocking is being reconstructed for LIRR's East Side Access project.[100][101]

New Brunswick–Trenton high-speed upgrade

[edit]In August 2011, Congress obligated $450 million to a six-year project to add capacity on one of the busiest segments on the NEC in New Jersey.[58] The project is designed to upgrade electrical power, signal systems and catenary wires on a 24-mile (39 km) section between New Brunswick and Trenton to improve reliability, increase speeds up to 160 mph (260 km/h), and support more frequent high-speed service.[102][103][104] The improvements were scheduled to be completed in 2016, but have been delayed repeatedly.[105] The track work is one of several projects planned for the "New Jersey Speedway" section of the NEC, which include a new station at North Brunswick, the Mid-Line Loop (a flyover for reversing train direction), and the re-construction of County Yard, to be done in coordination with NJ Transit.[106] Acela trains began operating at speeds up to 150 mph (240 km/h) between Princeton Junction and New Brunswick in June 2022. With the planned introduction of the Avelia Liberty in 2024, speeds will increase to 160 miles per hour (260 km/h).[107]

New trains for Acela

[edit]On August 26, 2016, Vice President Joe Biden announced a $2.45 billion federal loan package to pay for new Acela equipment, as well as upgrades to the NEC. The loans will finance 28 trainsets that will replace the existing fleet. The trains are being built by Alstom in Hornell and Rochester, New York. Passenger service using the new trains had been expected to begin in 2024, but as of September 2024 no start date has been announced. The current fleet is expected to be retired when all the replacements have been delivered. Amtrak will pay off the loans from increased NEC passenger revenue.[108]

Replacement of bridge over Hutchinson River

[edit]Amtrak has applied for $15 million for the environmental impact studies and preliminary engineering design to examine replacement options for the more than 100-year-old, low-level movable rail Pelham Bay Bridge (just west of Pelham Bridge) over the Hutchinson River in the Bronx that has been limiting speed and train capacity. The goal is for a new bridge to support expanded service and speeds up to 110 mph (180 km/h).[109]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Amtrak's Fiscal Year (FY) runs from October 1 of the prior year to September 30 of the named year.

- ^ "Amtrak Fiscal Year 2023 Ridership" (PDF). Amtrak. November 27, 2023. Retrieved November 30, 2023.

- ^ Young, Elise; Pogkas, Demetrios (March 5, 2018). "How Trump's Hudson Tunnel Feud Threatens the National Economy". Bloomberg News. New York: Bloomberg, L.P. Retrieved March 6, 2018.

- ^ Transportation Statistics Annual Report (PDF) (Report). Washington: Bureau of Transportation Statistics. November 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 21, 2014. Retrieved February 18, 2007.

- ^ "Amtrak fact sheet: Acela service" (PDF). Washington: National Association of Railroad Passengers. 2013. Retrieved May 6, 2016.

- ^ Wolmar, Christian (March 7, 2010). "High-Speed Rail Investment Should Focus on Acela". The New York Times. New York. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 6, 2016.

- ^ The Amtrak Vision for the Northeast Corridor: 2012 Update Report (PDF) (Report). Washington: Amtrak. July 17, 2012. Retrieved July 14, 2023.

- ^ Nussbaum, Paul (July 10, 2012). "Amtrak's high-speed Northeast Corridor plan at $151 billion". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Philadelphia. Archived from the original on July 14, 2012. Retrieved July 23, 2013.

- ^ "Open Pennsylvania Station to-night; First Regular Train to Use the Hudson River Tubes Starts at 12:02 A.M. Sunday". The New York Times. November 26, 1910. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 12, 2021.

- ^ "New Haven Road to Use Pennsylvania Terminal; Applies for Leave to Avail Itself of Port Chester Tracks. To Enter City by Tunnel Rapid Transit Board Directs That Connecting Railroad Franchise Be Taken Up Without More Delay". The New York Times. June 22, 1906. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 12, 2021.

- ^ Report of the Board of Railroad Commissioners, February 15, 1911, page 408

- ^ Churella 2013, pp. 222–223

- ^ Churella 2013, p. 358

- ^ Churella 2013, p. 357

- ^ Churella 2013, p. 744

- ^ a b c "Pennsylvania Opens Its Great Station; First Regular Train Sent Through the Hudson River Tunnel at Midnight". The New York Times. November 27, 1910. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 11, 2018.

- ^ a b c Thom, William G.; Sturm, Robert C. (2006). The New York Connecting Railroad. Long Island-Sunrise Chapter, National Railway Historical Society. p. 46. ISBN 9780988691605.

- ^ Sprague, J. L.; Cunningham, J. J. (2013). "A Frank Sprague Triumph: The Electrification of Grand Central Terminal [History]". IEEE Power and Energy Magazine. 11 (1): 58–76. doi:10.1109/mpe.2012.2222293. ISSN 1540-7977. S2CID 6729668.

- ^ Roberts, Sam (January 18, 2013). "The Birth of Grand Central Terminal". The New York Times. Retrieved November 8, 2015.

- ^ Sam Roberts (January 22, 2013). Grand Central: How a Train Station Transformed America. Grand Central Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4555-2595-9.

- ^ "WGBH American Experience: Grand Central". Boston: PBS. January 8, 1902. Retrieved November 8, 2015 – via WGBH Educational Foundation.

- ^ a b c Schlichting, Kurt C. (2001). Grand Central Terminal: Railroads, Architecture and Engineering in New York. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-6510-7.

- ^ Williams, Gray (2003). "Suburban Westchester". In Elizabeth G. Fuller; Katherine M. Hite (eds.). Picturing Our Past: National Register Sides in Westchester County. Elmsford, New York: Westchester County Historical Society. pp. 382–383. ISBN 978-0-915585-14-4.

- ^ "N.Y. Central Starts Its Electric Trains; Regular Service Begins with Four Yonkers Locals". The New York Times. December 12, 1906. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 1, 2021.

- ^ a b Burch, E.P. (1911). Electric Traction for Railway Trains: A Book for Students, Electrical and Mechanical Engineers, Superintendents of Motive Power and Others ... McGraw-Hill Book Company. p. 541. ISBN 978-1-9741-3212-6. Retrieved November 1, 2021.

- ^ "Central at Odds With New Haven; Mellen's Road Officials Think Price for Electric Current at Union Station High". The New York Times. July 2, 1907. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 1, 2021.

- ^ Goss, W.F.M. (1915). Smoke Abatement and Electrification of Railway Terminals in Chicago: Report of the Chicago Association of Commerce, Committee of Investigation on Smoke Abatement and Electrification of Railway Terminals. Rand, McNally. p. 635. Retrieved November 1, 2021.

- ^ Middleton 2001, p. 85

- ^ Ziel, R. (2013). The Long Island Rail Road in Early Photographs. Dover Transportation. Dover Publications. p. 108. ISBN 978-0-486-15760-3. Retrieved November 1, 2021.

- ^ a b Keller, D.; Lynch, S. (2005). Revisiting the Long Island Rail Road: 1925-1975. Images of Rail. Arcadia Publishing Incorporated. p. 14. ISBN 978-1-4396-3248-2. Retrieved November 1, 2021.

- ^ "Day Long Throng Inspects New Tube; 35,000 Persons Were Carried on the First Day of Pennsylvania's Tunnel Service". The New York Times. September 9, 1910. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- ^ "Pennsylvania Opens Its Great Station; First Regular Train Sent Through the Hudson River Tunnel at Midnight". The New York Times. November 27, 1910. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 23, 2018.

- ^ Electric Railway Journal. McGraw Hill Publishing Company. 1912. p. 893. Retrieved November 1, 2021.

- ^ Report. 1911. p. 1-PA9. Retrieved November 1, 2021.

- ^ Chamberlin, Clint. "Pennsylvania RR Electrification". North East Rails. Retrieved February 18, 2021.

- ^ Middleton 2001, p. 315

- ^ "P.R.R. WILL SPEND $77,000,000 AT ONCE; Atterbury Outlines Projects Under PWA Loan Giving Year's Work to 25,000. TO EXTEND ELECTRIC LINE Sees Buying Power Restored and Industry Stimulated by Wide Building Program". The New York Times. January 31, 1934. Retrieved August 8, 2012.

- ^ "N.Y.-Washington Electric Train Service Starts Sunday on P.R.R." The Daily Home News. New Brunswick, New Jersey. February 9, 1935. p. 3. Retrieved January 31, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Acses to speed NE Corridor". Railway Gazette International. September 1, 1998. Retrieved April 22, 2018.

- ^ William D. Middleton (December 1999). "Passenger rail in the 20th Century". Railway Age. Archived from the original on May 4, 2007. Retrieved November 13, 2006.

- ^ Hammer, Alexander R. (January 31, 1968). "Court Here Lets Railroads Consolidate Tomorrow". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 5, 2022.

- ^ "New Haven Sold to Penn Central; $145.6-Million Paid in Action Forced by Government Penn Central Reluctantly Absorbs the Bankrupt New Haven Line". The New York Times. January 1, 1969. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 5, 2022.

- ^ a b Baer, Christopher T. (April 2015). "A GENERAL CHRONOLOGY OF THE PENNSYLVANIA RAILROAD COMPANY ITS PREDECESSORS AND SUCCESSORS AND ITS HISTORICAL CONTEXT" (PDF). The Pennsylvania Railroad Technical & Historical Society. Retrieved May 6, 2016.

- ^ "A loss for Amtrak is Coleman's Gain". Business Week. September 13, 1976. p. 36.

- ^ United States Railway Association, Washington, D.C. (1975-07-26). Final System Plan for Restructuring Railroads in the Northeast and Midwest Region pursuant to the Regional Rail Reorganization Act of 1973. ("FSP"):

Vol. 1. Vol. 2 - ^ Amtrak to buy Northesast Corridor Modern Railways issue 333 June 1976 page 244

- ^ Amtrak, DOT agree on NE Corridor Railway Age September 13, 1976, page 8

- ^ a b U.S. Congress. Railroad Revitalization and Regulatory Reform Act of 1976, Pub. L. 94–210, 90 Stat. 31, 45 U.S.C. § 801. February 5, 1976. Sometimes referred to as the "4R Act."

- ^ USDOT. "NECIP Redirection Study."[dead link] January 1979. p. 1.

- ^ a b NEC Master Plan Working Group. "NEC Infrastructure Master Plan." May 2010. pp. 19–20.

- ^ "Building the Infrastructure for Acela Express". history.amtrak.com. Amtrak. February 25, 2016. Retrieved April 28, 2020.

- ^ "Copper trolley wire and a method of manufacturing copper trolley wire".

- ^ Middleton 2003, p. 38

- ^ Middleton 2001, pp. 431–432

- ^ "Amtrak's New High-Speed Service Is Derailed by Mechanical Problem". Associated Press. December 13, 2000 – via LA Times.

- ^ "Timetables (see Northeast Corridor 1–3)". Amtrak. Retrieved April 22, 2018.

- ^ Wald, Matthew (November 9, 2005). "Amtrak's President Is Fired by Its Board". New York Times. Retrieved May 14, 2015.

- ^ "Amtrak Releases Concept for 220 mph Train Along Northeast Corridor". AASHTO Journal. Archived from the original on October 7, 2010. Retrieved October 10, 2010.

- ^ a b Schned, Dan (August 24, 2011). "U.S. DOT Obligates $745 Million to Northeast Corridor Rail Projects". America 2050. Archived from the original on February 20, 2012. Retrieved November 24, 2011.

- ^ Frassinelli, Mike (September 25, 2012). "Amtrak train looks to break U.S. speed record in Northeast Corridor test". The Star-Ledger. Retrieved December 17, 2012.

- ^ "Amtrak tests of Acela express train at 165 MPH will not affect commuters | Science updates | NewJerseyNewsroom.com -- Your State. Your News". Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved November 24, 2013.

- ^ Higgs, Larry (September 14, 2017). "160 mph trains will speed from Trenton to New Brunswick by 2020". New Jersey On-Line. Retrieved December 27, 2017.

- ^ "New Jersey high speed rail improvement program", Amtrak, retrieved November 10, 2020

- ^ "NEC FUTURE: Tier 1 Final EIS". NEC Future. Retrieved April 22, 2018.

- ^ Guse, Clayton (June 2, 2021). "A 100-minute train ride to Boston: New York, New England lawmakers push high-speed service on tracks that would include Long Island Sound tunnel". nydailynews.com. Retrieved December 31, 2021.

- ^ Mouawad, Jad (May 14, 2015). "Technology That Could Have Prevented Amtrak Derailment Was Absent". The New York Times.

- ^ Nussbaum, Paul; Wood, Anthony R. (May 14, 2015). "Automatic braking was in place on other side of curve". The Philadelphia Inquirer.

- ^ "Rear-End Collision of Amtrak Passenger Train 94, The Colonial and Consolidated Rail Corporation Freight Train ENS-121, on the Northeast Corridor on January 4, 1987" (PDF). NTSB. January 25, 1988.

- ^ "Interstate Commerce Commission, Investigation No. 2726, The Pennsylvania Railroad Co. Report: IN RE; Accident at Shore, PA., on September 6, 1943". October 1, 1943. Archived from the original on May 13, 2015.

- ^ "Still No Answers in May Amtrak Power Outage". WNYC. June 22, 2006. Retrieved November 13, 2006.

- ^ Tom Baldwin (June 23, 2006). "Amtrak: Cause of power outage unknown". Courier-Post. Retrieved November 13, 2006. [dead link]

- ^ "Malloy: 'Catastrophic Failure' On Metro-North New Haven Line". CBS New York. September 26, 2013. Retrieved October 5, 2013.

- ^ a b "Crossing Inventory Report". Federal Railroad Administration. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- ^ "Section 4: Identification of Alternatives". Railroad-Highway Grade Crossing Handbook (2 ed.). Federal Highway Administration. August 2007. Archived from the original on May 23, 2015. Retrieved March 22, 2015.

- ^ "49 U.S.C. 24906 – ELIMINATING HIGHWAY AT-GRADE CROSSINGS". U.S. Government Publishing Office. Retrieved March 22, 2015.

- ^ a b Dee, Jane E. (March 29, 1999). "Rail Crossings Safety Issue For Amtrak". Hartford Courant. Retrieved March 22, 2015.

- ^ "Stuck crossing gate strands drivers on wrong side of the tracks". The Day. November 4, 1999. Retrieved March 22, 2015.

- ^ O'Donnell, Noreen (February 5, 2015). "Technology Solution? Sensors Could Warn Trains of Cars on Tracks". NBC Bay Area. Retrieved March 22, 2015.

- ^ Dee, Jane E. (September 9, 1999). "Amtrak To Put Up 7 Safer Gates". Hartford Courant. Retrieved March 22, 2015.

- ^ McGeehan, Patrick & Wald, Matthew L. (September 30, 2005). "High-Tech Gates Fail to Avert Car-Train Crash". The New York Times. Retrieved September 2, 2008.

- ^ "Investigators Seek Answers In Fatal Crash That Killed Two; Cause of Waterford car-train accident may never be known". The New London Day. September 30, 2005.

- ^ "Family sues over fatal car crash on railroad tracks". The Boston Globe. Associated Press. December 27, 2006. Archived from the original on December 27, 2008.

- ^ "Passenger ridership" (PNG). Amtrak. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved November 5, 2015.

- ^ Amtrak FY16 Ridership and Revenue Fact Sheet (PDF) (Report). Washington: Amtrak. April 7, 2017. Retrieved October 13, 2017.

- ^ Amtrak FY18 Ridership (PDF) (Report). Washington: Amtrak. Retrieved November 27, 2019.

- ^ Amtrak FY19 Ridership (PDF) (Report). Washington: Amtrak. Retrieved November 27, 2019.

- ^ Amtrak FY20 Ridership (PDF) (Report). Washington: Amtrak. Retrieved September 9, 2021.

- ^ Amtrak FY21 Ridership (PDF) (Report). Washington: Amtrak. Retrieved May 24, 2023.

- ^ Amtrak FY22 Ridership (PDF) (Report). Washington: Amtrak. Retrieved May 24, 2023.

- ^ Amtrak FY23 Ridership (PDF) (Report). Washington: Amtrak. Retrieved September 3, 2024.

- ^ Congressional Budget Office. "The Past and Future of U.S. Passenger Rail Service," September 2003.[1]

- ^ O'Toole, Randal (June 29, 2011). "Intercity Buses: The Forgotten Mode". Policy Analysis (680).

- ^ Nixon, Ron. (2012, August 16.) Trading Planes for Trains: Riders Weary of Patdowns and Delays Set Records for Amtrak. The New York Times, p. B1 [2]

- ^ Hartley, Scott A. (April 2016). "The key to Providence & Worcester's success: Reinvention". Trains Magazine. pp. 53–55. OCLC 945631712.

- ^ "Providence and Worcester Railroad". Genesee & Wyoming. Retrieved April 22, 2018.

- ^ "Gateway Project" (PDF). Amtrak. February 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 7, 2011. Retrieved February 7, 2011.

- ^ "Maloney Hails Federal Grant to Ease Amtrak Delays in NYC, Spur High-Speed Rail in NE Corridor – $294.7 Million Grant to Improve "Harold Interlocking", a Delay-Plagued Junction For Trains in the NE Corridor". Congresswoman Carolyn B. Maloney. May 9, 2011. Archived from the original on September 28, 2011. Retrieved May 13, 2011.

- ^ Colvin, Jill (May 9, 2011). "New York Awarded $350 Million for High-Speed Rail Projects". DNAinfo.com. Archived from the original on September 8, 2015. Retrieved May 13, 2011.

- ^ "House Vote Jeopardizes Key Northeast Rail Projects". Back on Track: Northeast. The Business Alliance for Northeast Mobility. July 20, 2011. Archived from the original on September 30, 2011. Retrieved July 21, 2011.

- ^ "Harold Interlocking Northeast Corridor Congestion Relief Project". Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Retrieved April 30, 2016.

- ^ Castillo, Alfonso A. (March 1, 2018). "MTA: Another snag for East Side Access project". Newsday. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- ^ "LIRR to test upgraded signal system for East Side Access project. For Railroad Career Professionals". Progressive Railroading. April 5, 2018. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- ^ Frassinelli, Mike (May 9, 2011). "Feds steer $450M to N.J. for high-speed rail". The Star Ledger. Retrieved May 13, 2011.

- ^ Thorbourne, Ken (May 9, 2011). "Amtrak to receive nearly $450 million in high speed rail funding". The Jersey Journal. Retrieved May 13, 2011.

- ^ McGeehan, Patrick (May 9, 2011), "Florida's rejected rail funds flow north", The New York Times, retrieved May 13, 2011

- ^ "New Jersey High-Speed Rail Improvement Program". Amtrak. Retrieved May 14, 2019.

- ^ Vantuono, William C (June 11, 2013). "Amtrak sprints toward a higher speed future". Railway Age. Retrieved January 19, 2014.

- ^ Abrams, Jason (June 14, 2022). "Amtrak Increasing Speed of Acela Trains in New Jersey Through Infrastructure Investments and Improvements". Amtrak. Retrieved June 20, 2022.

- ^ Aratani, Lori (August 26, 2016). "Biden announces upgrades for Amtrak's Northeast Corridor". The Washington Post.

- ^ "Amtak Seeks $1.3 billion for Gateway Project and Next-Generation High-Speed Rail on Northeast Corridor". Amtrak. April 4, 2011. Archived from the original on May 3, 2011. Retrieved April 8, 2011.

References

[edit]- Churella, Albert J. (2013). The Pennsylvania Railroad: Volume I, Building an Empire, 1846–1917. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-4348-2. OCLC 759594295.

- Cudahy, Brian J. (2002), Rails Under the Mighty Hudson (2nd ed.), New York: Fordham University Press, ISBN 978-0-82890-257-1, OCLC 911046235

- Middleton, William D. (2001) [1974]. When the Steam Railroads Electrified (2nd ed.). Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-33979-9. OL 2510988W.

- Middleton, William D. (March 2003). "Super Railroad". Trains. 63 (3): 36–59. ISSN 0041-0934.

Further reading

[edit]- The Amtrak Vision for the Northeast Corridor – 2012 Update Report – July 2012

- Northeast Corridor Infrastructure Master Plan – June 2010

- Geddes, Richard Northeast Corridor Future: Options for High-Speed Rail Development and Opportunities for Private-Sector Participation: Hearing Before the Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure, House of Representatives, One Hundred Twelfth Congress, Second Session, December 13, 2012

- New York Division (Map). Pennsylvania Railroad. 1963.

- Alff, David (2024) The Northeast Corridor: The Trains, the People, the History, the Region. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-82283-9

- Spavins, Jim. (2010) Diesels on the Northeast Corridor (1st ed.). ISBN 1-4537-8765-8

External links

[edit]- The Northeast Corridor Commission

- The Northeast Corridor – Amtrak

- NEC Future: A Rail Investment plan for the Northeast Corridor at the Wayback Machine (archived December 6, 2015)

- Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) No. MA-19, "Northeast Railroad Corridor"

- HAER No. RI-19, "Northeast Railroad Corridor"

- HAER No. CT-11, "Northeast Railroad Corridor"

- HAER No. NY-121, "Northeast Railroad Corridor"

- HAER No. NJ-40, "Northeast Railroad Corridor"

- HAER No. PA-71, "Northeast Railroad Corridor"

- HAER No. DE-21, "Northeast Railroad Corridor"

- HAER No. MD-45, "Northeast Railroad Corridor"

- HAER No. DC-3, "Northeast Railroad Corridor"

- Video: "A Short History of A Short Stretch of Amtrak's Northeast Corridor", Bradley Peniston, August 26, 2015. Animated look at the development of the Philadelphia rights-of-way that became part of the Northeast Corridor.

- Northeast Corridor

- High-speed railway lines in the United States

- Pennsylvania Railroad lines

- Philadelphia, Baltimore and Washington Railroad lines

- New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad lines

- Old Colony Railroad lines

- Transportation in New England

- Electric railways in Washington, D.C.

- Electric railways in Maryland

- Electric railways in Delaware

- Electric railways in Pennsylvania

- Electric railways in New Jersey

- Electric railways in New York (state)

- Electric railways in Connecticut

- Electric railways in Rhode Island

- Electric railways in Massachusetts

- Historic American Engineering Record in Washington, D.C.

- Historic American Engineering Record in Maryland

- Historic American Engineering Record in Delaware

- Historic American Engineering Record in Pennsylvania

- Historic American Engineering Record in New Jersey

- Historic American Engineering Record in New York (state)

- Historic American Engineering Record in Connecticut

- Historic American Engineering Record in Rhode Island

- Historic American Engineering Record in Massachusetts

- Passenger rail transportation in Washington, D.C.

- Passenger rail transportation in Maryland

- Passenger rail transportation in Delaware

- Passenger rail transportation in Pennsylvania

- Passenger rail transportation in New Jersey

- Passenger rail transportation in New York (state)

- Passenger rail transportation in Connecticut

- Passenger rail transportation in Rhode Island

- Passenger rail transportation in Massachusetts

- Rail infrastructure in Washington, D.C.

- Rail infrastructure in Maryland

- Rail infrastructure in Delaware

- Rail infrastructure in Pennsylvania

- Rail infrastructure in New Jersey

- Rail infrastructure in New York (state)

- Rail infrastructure in Connecticut

- Rail infrastructure in Rhode Island

- Rail infrastructure in Massachusetts

- Railway lines in the United States

- Northeastern United States

- Conrail lines

- 1834 establishments in the United States

- Railway lines opened in 1834

- 25 kV AC railway electrification

- Transport corridors

- Amtrak route networks