Cormohipparion

| Cormohipparion | |

|---|---|

| |

| C. occidentale skeleton | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Perissodactyla |

| Family: | Equidae |

| Subfamily: | Equinae |

| Tribe: | †Hipparionini |

| Genus: | †Cormohipparion Skinner & MacFadden, 1977 |

| Type species | |

| †Hipparion occidentale | |

| Subgenera and species | |

|

†Cormohipparion

†Notiocradohipparion

| |

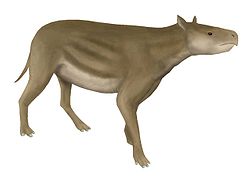

Cormohipparion (Greek: "noble" (cormo), "pony" (hipparion)[1] is an extinct genus of horse belonging to the tribe Hipparionini that lived in North America and Eurasia during the late Miocene to Pliocene (Hemphillian to Blancan in the NALMA classification).[2] They grew up to 3 feet (0.91 meters) long.[3][4]

Taxonomy

[edit]

The genus Cormohipparion was coined for the extinct hipparionin horse "Equus" occidentale, described by Joseph Leidy in 1856.[5] However it was soon argued that the partial material fell within the range of morphological variation seen in Hipparion, and that the members of Cormohipparion belonged instead within Hipparion.[6][7] This rested on claims that pre-orbital morphology did not have any taxonomic significance, a claim that detailed study of quarry sections later showed to be false.[8] The genus was originally identified by a closed off preorbital fossa, but later examinations of the cheek teeth, specifically the lower cheek teeth, of Cormohipparion specimens found that they were indeed valid and distinct from Hipparion.[9] A reappraisal of many horse genera was thus conducted in 1984,[10] and the proposed synonymy was not acknowledged by later literature.[11] C. ingenuum holds the distinction for being the first prehistoric horse to be described in Florida, as well as being one of the most common species of extinct three-toed horses found to be in Florida, lasting until the early Pliocene.[12][13] Cormohipparion emsliei has the distinction of being the last hipparion horse known from the fossil record.[14]

The genus is considered to represent an ancestor to Hippotherium.[15] Its fossils have been recovered from as far south as Mexico.[16] Fossils have been found in the Great Plains and Rio Grande regions of North America, Mexico, Florida, and Texas, which shows that they were herding animals.[17][18][19][20] Fossils have been unearthed in California,[21] Louisiana,[22][23] Nebraska,[24][25] South Dakota,[26], Honduras,[27] Costa Rica,[28] and Panama.[29] Fossils have also been found in India and Turkey.[30][31]

Evolution

[edit]

A species of Cormohipparion closely related to C. occidentale is thought to have crossed the Bering land Bridge over into Eurasia around 11.4-11 million years ago, becoming the ancestor to Old World hipparionines.[32]

References

[edit]- ^ C. Hulbert Jr., Richard (October 17, 2013). "Cormohipparion ingenuum". Florida Vertebrate Fossils. Retrieved 2025-04-09.

- ^ MacFadden, Bruce J.; Skinner, Morris F. (1982). "Hipparion Horses and Modern Phylogenetic Interpretation: Comments on Forsten's View of Cormohipparion". Journal of Paleontology. 56 (6): 1336–1342. ISSN 0022-3360. JSTOR 1304670.

- ^ "Region 4: The Great Plains". geology.teacherfriendlyguide.org. Retrieved 2021-06-23.

- ^ Czaplewski, Nicholas J.; Thurmond, J. Peter; Wyckoff, Don G. (Fall 2001). "Wild Horse Creek #1: A Late Miocene (Clarendonian-Hemphillian) Vertebrate Fossil Assemblage in Roger Mills County, Oklahoma" (PDF). Oklahoma Geology. 61 (3): 60–67.

- ^ Skinner, M. F.; MacFadden, B. J. (1977). "Cormohipparion n. gen. (Mammalia, Equidae) from the North American Miocene (Barstovian-Clarendonian)". Journal of Paleontology. 51 (5). Paleontological Society: 912–926. JSTOR 1303763.

- ^ Forsten, A. (1982). "The Status of the Genus Cormohipparion Skinner and MacFadden (Mammalia, Equidae)". Journal of Paleontology. 56 (6). Paleontological Society: 1332–1335. JSTOR 1304669.

- ^ MacFadden, Bruce J. (1985). "Patterns of Phylogeny and Rates of Evolution in Fossil Horses: Hipparions from the Miocene and Pliocene of North America". Paleobiology. 11 (3): 245–257. Bibcode:1985Pbio...11..245M. doi:10.1017/S009483730001157X. ISSN 0094-8373. JSTOR 2400665. S2CID 89569817.

- ^ MacFadden, B. J.; Skinner, M. F. (1982). "Hipparion Horses and Modern Phylogenetic Interpretation_ Comments on Forsten's View of Cormohipparion". Journal of Paleontology. 56 (6). Paleontological Society: 1336–1342. JSTOR 1304670.

- ^ Forsten, Ann (1982). "The Status of the Genus Cormohipparion Skinner and MacFadden (Mammalia, Equidae)". Journal of Paleontology. 56 (6): 1332–1335. ISSN 0022-3360. JSTOR 1304669.

- ^ MacFadden, BJ (1984). "Systematics and phylogeny of Hipparion, Neohipparion, Nannippus, and Cormohipparion (Mammalia, Equidae) from the Miocene and Pliocene of the new world". American Museum of Natural History.

- ^ Hulbert Jr, R. C. (1988). "A New Cormohipparion (Mammalia, Equidae) from the Pliocene (Latest Hemphillian and Blancan) of Florida". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 7 (4). The Society of Vertebrate Paleontology: 451–468. Bibcode:1988JVPal...7..451H. doi:10.1080/02724634.1988.10011675. JSTOR 4523166.

- ^ "Cormohipparion ingenuum". Florida Museum. 2017-03-30. Retrieved 2021-06-16.

- ^ "Late Pliocene (Late Blancan) vertebrates from the St. Petersburg Times site, Pinellas County, Florida, with a brief review of Florida Blancan faunas | WorldCat.org". search.worldcat.org. Retrieved 2025-04-09.

- ^ "Neohipparion". Florida Museum. 2018-02-16. Retrieved 2021-06-26.

- ^ Woodburne, M. O. (2005). "A New Occurrence of Cormohipparion, with Implications for the Old World Hippotherium Datum". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 25: 256–257. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2005)025[0256:ANOOCW]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0272-4634. S2CID 86241044.

- ^ Bravo-Cuevas, V. M.; Ferrusquía-Villafranca, I. (2008). "Cormohipparion (Mammalia, Perissodactyla, Equidae) from the Middle Miocene of Oaxaca, Southeastern Mexico". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 28: 243–250. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2008)28[243:CMPEFT]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0272-4634. S2CID 131613568.

- ^ Skinner, Morris F.; MacFadden, Bruce J. (1977). "Cormohipparion n. gen. (Mammalia, Equidae) from the North American Miocene (Barstovian-Clarendonian)". Journal of Paleontology. 51 (5): 912–926. ISSN 0022-3360. JSTOR 1303763.

- ^ Bravo-Cuevas, Victor Manuel; Ferrusquía-Villafranca, Ismael (2008). "Cormohipparion (Mammalia, Perissodactyla, Equidae) from the Middle Miocene of Oaxaca, Southeastern Mexico". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 28 (1): 243–250. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2008)28[243:CMPEFT]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0272-4634. JSTOR 30126348. S2CID 131613568.

- ^ Hulbert, Richard C. (1988). "A New Cormohipparion (Mammalia, Equidae) from the Pliocene (Latest Hemphillian and Blancan) of Florida". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 7 (4): 451–468. Bibcode:1988JVPal...7..451H. doi:10.1080/02724634.1988.10011675. ISSN 0272-4634. JSTOR 4523166.

- ^ MacFadden, Bruce J.; Skinner, Morris F. (1981). "Earliest Holarctic Hipparion, Cormohipparion goorisi n. sp. (Mammalia, Equidae), from the Barstovian (Medial Miocene) Texas Gulf Coastal Plain". Journal of Paleontology. 55 (3): 619–627. ISSN 0022-3360. JSTOR 1304276.

- ^ WHISTLER, DAVID P.; BURBANK, DOUGLAS W. (1992-06-01). "Miocene biostratigraphy and biochronology of the Dove Spring Formation, Mojave Desert, California, and characterization of the Clarendonian mammal age (late Miocene) in California". GSA Bulletin. 104 (6): 644–658. Bibcode:1992GSAB..104..644W. doi:10.1130/0016-7606(1992)104<0644:MBABOT>2.3.CO;2. ISSN 0016-7606.

- ^ Schiebout, Judith A.; Ting, Suyin; Williams, Michael; Boardman, Grant; Gose, Wulf (2004-04-01). Paleofaunal and Environmental Research on Miocene Fossil Sites TVOR SE and TVOR S on Fort Polk, Louisiana, with Continued Survey, Collection, Processing, and Documentation of other Miocene Localities (Report). Fort Belvoir, VA: Defense Technical Information Center. doi:10.21236/ada422018.

- ^ "Abstract: TERRESTRIAL CARNIVORES, ARTIODACTYLS, PERISSODACTYLS, AND PROBOSCIDEANS OF THE FORT POLK MIOCENE SITES OF LOUISIANA (South-Central Section - 45th Annual Meeting (27–29 March 2011))". gsa.confex.com. Retrieved 2025-04-09.

- ^ Otto, Rick (2017-01-01). "Five Species of Fossil Equids Preserved In-situ at Ashfall Fossil Beds". University of Nebraska State Museum: Programs Information.

- ^ Tucker, S. T.; Otto, R. E.; Joeckel, R. M.; Voorhies, M. R. (2014-01-01), Korus, Jesse T. (ed.), "The geology and paleontology of Ashfall Fossil Beds, a late Miocene (Clarendonian) mass-death assemblage, Antelope County and adjacent Knox County, Nebraska, USA", Geologic Field Trips along the Boundary between the Central Lowlands and Great Plains: 2014 Meeting of the GSA North – Central Section, vol. 36, Geological Society of America, p. 0, ISBN 978-0-8137-0036-6, retrieved 2025-04-09

- ^ Pagnac, Darrin. "Additions to the Vertebrate Faunal Assemblage of the Middle Miocene Fort Randall Formation in the Vicinity of South Bijou Hill, South Dakota, U.S.A".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Webb, S. David; Perrigo, Stephen C. (1984). "Late Cenozoic Vertebrates from Honduras and El Salvador". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 4 (2): 237–254. Bibcode:1984JVPal...4..237W. doi:10.1080/02724634.1984.10012006. ISSN 0272-4634. JSTOR 4522986.

- ^ Miller, Stephanie; Valerio, Ana L.; Sudasassi, Arturo; Laurito, César A. (2022). "Cormohipparion quinni (Mammalia, Equidae, Hipparionini) del Mioceno Medio (Barstoviano Tardío) del Norte de Costa Rica". Revista geológica de América central (in Spanish). 66: 1–8. doi:10.15517/rgac.v66i0.49763. ISSN 2215-261X.

- ^ MacFadden, Bruce J.; Jones, Douglas S.; Jud, Nathan A.; Moreno-Bernal, Jorge W.; Morgan, Gary S.; Portell, Roger W.; Perez, Victor J.; Moran, Sean M.; Wood, Aaron R. (2017). "Integrated Chronology, Flora and Faunas, and Paleoecology of the Alajuela Formation, Late Miocene of Panama". PLOS ONE. 12 (1): e0170300. Bibcode:2017PLoSO..1270300M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0170300. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 5249130. PMID 28107398.

- ^ Basu, Prabir Kumar (2004-01-01). "Siwalik mammals of the Jammu Sub-Himalaya, India: an appraisal of their diversity and habitats". Quaternary International. 5th International conference on the cenozoic evolution of the Asia-Pacific environment. 117 (1): 105–118. Bibcode:2004QuInt.117..105B. doi:10.1016/S1040-6182(03)00120-4. ISSN 1040-6182.

- ^ Bernor, Raymond Louis; Ataabadi, Majid Mirzaie; Basoglu, Oksan; Cirilli, Omar; Kaya, Ferhat; Pehlevan, Cesur; Niknahad, Mansoureh; Vaziri, Mohammad Reza; Arab, Ahmad Lotfabad (November 2024). "Cormohipparion cappadocium, a new species from the Late Miocene of Yeniyaylacık, Türkiye, and the emergence of western Eurasian hipparion bioprovinciality". Annales Zoologici Fennici. 61 (1). doi:10.5735/086.061.0119. ISSN 0003-455X. Archived from the original on 2025-03-29.

- ^ Bernor, Raymond L.; Kaya, Ferhat; Kaakinen, Anu; Saarinen, Juha; Fortelius, Mikael (October 2021). "Old world hipparion evolution, biogeography, climatology and ecology". Earth-Science Reviews. 221: 103784. Bibcode:2021ESRv..22103784B. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2021.103784.

- Miocene horses

- Pliocene horses

- Zanclean genera

- Messinian genera

- Tortonian genera

- Langhian genera

- Serravallian genera

- Miocene mammals of North America

- Pliocene mammals of North America

- Hemphillian

- Blancan

- Neogene Honduras

- Neogene Mexico

- Neogene Panama

- Neogene United States

- Fossils of Honduras

- Fossils of Mexico

- Fossils of Panama

- Fossils of the United States

- Fossil taxa described in 1977

- Hipparionini