Cuilcagh

| Cuilcagh | |

|---|---|

Northern slopes | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 666 m (2,185 ft)[1] |

| Prominence | 570 m (1,870 ft)[1] |

| Listing | County Top (Cavan and Fermanagh), P600, Marilyn, Hewitt |

| Coordinates | 54°12′00″N 7°48′40″W / 54.200°N 7.811°W |

| Naming | |

| Native name | Binn Chuilceach (Irish) |

| English translation | "calcareous/chalky peak" |

| Pronunciation | Irish: [ˌbʲiːn̠ʲ ˈxɪlʲcəx] English: /ˈkʌlkə/ |

| Geography | |

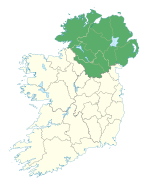

| Location | County Fermanagh, Northern Ireland and County Cavan, Republic of Ireland |

| OSI/OSNI grid | H123280 |

| Topo map | OSi Discovery 26 |

| Climbing | |

| Easiest route | Cuilcagh Boardwalk Trail (Stairway to Heaven) |

| Official name | Cuilcagh Mountain |

| Designated | 31 December 1998 |

| Reference no. | 968[2] |

Cuilcagh (from Irish Binn Chuilceach, meaning 'chalky peak'[3]) is a mountain on the border between County Fermanagh (in Northern Ireland) and County Cavan (in the Republic of Ireland). With a height of 666 metres (2,185 ft) it is the highest point in both counties. It is also the 170th highest peak on the island of Ireland, and Ireland's only cross-border county top.[4] Water from the southern slope flows underground until it emerges some miles away in the Shannon Pot, the traditional source of the River Shannon. The area is sometimes referred to as the Cuilcagh Mountains.[1][5]

Naming

[edit]The name Cuilcagh comes from the Irish Cuilceach, which has been translated as "chalky". However, the mountain is mainly sandstone and shale, covered with bog and heather. The cliff-edged summit surface of the mountain is formed from the hard-wearing Lackagh Sandstone which itself overlies the Briscloonagh Sandstone. "It is possible that the name refers to the limestone rock on the lower northern flanks, namely the Glencar and Dartry Limestone formations.[6] Here a number of streams disappear below ground at swallow holes named Cats Hole, Pollawaddy, Pollasumera and Polliniska, all forming part of the Marble Arch cave system. If so, the name would mean 'calcareous' rather than 'chalky'".[7] It has also been called Slieve Cuilcagh in English,[8] 'Slieve' being an anglicisation of Sliabh ("mountain").

In the 1609 Plantation of Ulster, Cuilcagh formed part of lands which were granted to John Sandford of Castle Doe by letters patent dated 7 July 1613 (Pat. 11 James I – LXXI – 38, Quilkagh).[9][10] It was later sold by Sandford to his wife's uncle Toby Caulfeild, 1st Baron Caulfeild, Master of the Ordnance and Caulfield had the sale confirmed by letters patent of 12 July 1620 (Pat. 19 James I. XI. 45, Quilkagh).

Nature

[edit]The Cuilcagh area supports a rich assemblage of upland insects, and is one of the most important sites in Ireland for these species. Species recorded include the water beetles Agabus melanarius, Agabus arcticus, Dytiscus lapponicus, Stictotarsus multilineatus, Hydroporus longicornis and Hydroporus morio and the water bugs Glaenocorisa propinqua and Callicorixa wollastoni. Lough Atona is the main locality for these species.[11]

Conservation

[edit]The Cuilcagh Mountain Park was opened by Fermanagh District Council in 1998.[12]

Ramsar site

[edit]The Cuilcagh Mountain Ramsar site (wetlands of international importance designated under the Ramsar Convention), is 2744.45 hectares in area, at latitude 54 13 26 N and longitude 07 48 17 W. It was designated a Ramsar site on 31 December 1998.

Geopark

[edit]In 2001 the Cuilcagh Mountain Park was joined with popular tourist attraction the Marble Arch Caves and the Cladagh Glen Nature Reserve to make one of the first UNESCO-recognised European Geoparks.[12] This became a Global Geopark in 2004. In September 2008 the Marble Arch Caves Global Geopark was expanded into County Cavan, making it the world's first transnational cross-border Geopark.[12] The Geopark is protected and managed by Fermanagh & Omagh District Council through the staff of the Marble Arch Caves Visitor Centre.[12]

Boardwalk trail

[edit]

In 2015, the Cuilcagh Boardwalk Trail or Cuilcagh Legnabrocky Trail (also called "The Stairway to Heaven") was opened up to preserve and protect the underlying peatland bog from erosion; however, the trail led to a dramatic rise in visitors to Cuilcagh from circa 3,000 per annum to over 60,000.[13] The popularity of the trail has led to concerns over the ability of the area to handle the increased visitors to the trail.[14]

Starting from the Legnabrocky Car Park (paid parking), the trail is over 6 kilometres long to the top (or over 7 kilometres starting from the nearby Marble Arch Caves car park). The first 5 kilometres are on a wide undulating gravel track, while the final kilometre involves climbing 450 wooden steps to a viewing gallery at the top of the route (which is close to the top of Cuilcagh mountain itself). Walkers are advised to allow 2.5–3.5 hours to complete the full 12–14 kilometre round-trip journey.[15][16]

Gallery

[edit]-

View from the summit

-

Benaughlin viewed from South Fermanagh with Cuilcagh on left

-

Boardwalk section of "Stairway to Heaven"

See also

[edit]- Sliabh Beagh

- Lists of mountains in Ireland

- Lists of mountains and hills in the British Isles

- List of P600 mountains in the British Isles

- List of Marilyns in the British Isles

- List of Hewitt mountains in England, Wales and Ireland

Further reading

[edit]- Brown, Leslie (2005). Inception and subsequent development of conduits in the Cuilcagh karst, Ireland (doctoral). Doctoral thesis, University of Huddersfield. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Cuilcagh/Cuilcagh Mountains". MountainViews Online Database. Retrieved 27 November 2019.

- ^ "Cuilcagh Mountain". Ramsar Sites Information Service. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- ^ "Place Names NI - Home". www.placenamesni.org. Archived from the original on 25 July 2018. Retrieved 4 August 2021.

- ^ "Cuilcagh". Mountainviews.ie. Retrieved 19 May 2007.

- ^ John G. O'Dwyer (26 November 2019). "Blow off the Christmas cabin-fever with a walk for the season". The Irish Times. Retrieved 27 November 2019.

Generally known as the Stairway to Heaven, this consists of a well-constructed new trail that conveys walkers high into the Cuilcagh Mountains.

- ^ "GSNI GeoIndex". mapapps2.bgs.ac.uk.

- ^ Tempan, Paul. Irish Hill and Mountain Names. MountainViews.ie.

- ^ Fullarton, A (1856). A Gazetteer of the World: Volume 3. Royal Geographical Society. p. 527.

- ^ Chancery, Ireland (1800). Calendar of the Patent Rolls of the Chancery of Ireland.

- ^ "Calendar of the state papers, relating to Ireland, of the reign of James I. 1603-1625. Preserved in Her Majesty's Public Record Office, and elsewhere". London, Longman. 4 August 1872 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Designated and Proposed Ramsar sites in Northern Ireland" (PDF). Joint Nature Conservation Committee. Retrieved 7 July 2008.

- ^ a b c d "Marble Arch Caves Global Geopark – IRELAND". European Geoparks Network. Retrieved 16 August 2014.

- ^ Andrea Smith (2 May 2017). "Why this 'Stairway to Heaven' in Ireland has become a social media star". Lonely Planet. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

Nicknamed the 'stairway to heaven,' the boardwalk opened in 2015 with an aim of conserving pristine blanket bog and restoring damaged peatland that had been eroded by people walking through it.

- ^ Chris McCullough (29 April 2017). "How Fermanagh's amazing 'stairway to heaven' has become a victim of its own success". Belfast Telegraph. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

- ^ "The Cuilcagh Boardwalk Trail (Stairway to Heaven): Route Information". Marble Arch Caves. Retrieved 5 June 2022.

- ^ Mark McConville (17 April 2019). "WATCH: Ireland's very own Stairway to Heaven! Weekend walk, anyone?". Irish Independent. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

The stunning wooden structure is found on Fermanagh's Cuilcagh Way - specifically, along the 7.5 km Legnabrocky trail.

External links

[edit]- Cuilcagh Boardwalk Trail, WalkNI (2018)

- Ireland's own "Stairway to Heaven" (Cuilcagh Boardwalk Trail, Irish Independent (April 2017)

- Cuilcagh Legnabrocky Boarded Mountain Trail, Marble Arch Caves Global Geopark (July 2015)

×a`