Didcot power stations

| Didcot Power Station | |

|---|---|

Didcot Power Station, including the former Didcot A. Viewed from the south in September 2006 | |

| |

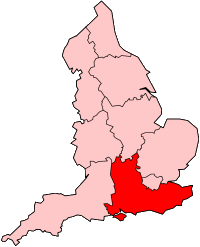

| Country | England |

| Location | Oxfordshire, South East England |

| Coordinates | 51°37′25″N 1°16′03″W / 51.62363°N 1.26757°W |

| Construction began | 1964 (Didcot A) 1994 (Didcot B) |

| Commission date | 30 September 1970 (Didcot A)[1] 1997 (Didcot B) |

| Decommission date | 22 March 2013 (Didcot A)[2][3] |

| Operators | Central Electricity Generating Board (1970–1990) National Power (1990–2000) Innogy plc (2000–2002) RWE Generation UK (2002–present) |

| Thermal power station | |

| Primary fuel | Natural gas |

| Secondary fuel | Biofuel |

| Power generation | |

| Nameplate capacity | 1,440 MW |

| External links | |

| Commons | Related media on Commons |

grid reference SU508919 | |

Didcot power station (Didcot B Power Station) is an active natural gas power plant that supplies the National Grid. A combined coal and oil power plant, Didcot A, was the first station on the site, which opened in 1970[4][5] and was demolished between 2014 and 2020.[6] The power station is situated in Sutton Courtenay, near Didcot in Oxfordshire, England. Didcot OCGT is a gas-oil power plant, originally part of Didcot A and now independent. It continues to provide emergency backup power for the National Grid.

A large section of the boiler house at Didcot A Power Station collapsed on 23 February 2016 while the building was being prepared for demolition. Four men were killed in the collapse. The combined power stations featured a chimney, demolished in 2020, which was one of the tallest structures in the UK, and could be seen from much of the surrounding landscape. It previously had six hyperboloid cooling towers, with three demolished in 2014 and the remaining three in 2019. RWE Npower applied for a certificate of immunity from English Heritage, to stop the towers being listed, to allow their destruction.[7] In February 2020, the final chimney of Didcot A was demolished.[8]

Didcot A

[edit]History

[edit]Didcot A Power Station was a coal and gas-fired power station designed by architect Frederick Gibberd. One of the Hinton Heavies, construction of the 2,000 MWe power station for the Central Electricity Generating Board began during 1964, and was completed in 1968 at a cost of £104m.[9] Up to 2,400 workers were employed at peak times. The station began generating power on 30 September 1970.[1]

It was located on a 1.2 square kilometres (300 acres) site, formerly part of the Ministry of Defence Central Ordnance Depot. A vote was held in Didcot and surrounding villages on whether the power station should be built. There was strong opposition from Sutton Courtenay but the yes vote was carried, due to the number of jobs that would be created in the area.

The main chimney was 200 m (660 ft) tall[10] with the six cooling towers 114 m (374 ft)[11] each. The cooling towers were arranged in two groups of three. These were located to the north west and to the south of the main building. The original design was for eight cooling towers but the consultant architect Frederick Gibberd proposed that the number be reduced to six to mitigate the visual impact of the station. The consequent limitation in cooling capability reduced the overall thermal efficiency of the power station.[12]

English Heritage declined to give listed building status to Didcot A Power Station in 2013. Though it recognised there were some interesting features, for example the "carefully designed" setting and Gibberd's detailing, there were better examples elsewhere.[13] The station ceased operation on 22 March 2013.[3][2]

Operation

[edit]The station used four 500 MWe generating units. In 2003 Didcot A burnt 3.7Mt of coal. The station burned mostly pulverised coal, but later also co-fired with natural gas. Didcot was the first large power station to be converted to have this function. A small amount of biomass, such as sawdust, was burned at the plant. This was introduced to try to depend more on renewable sources following the introduction of the Kyoto Protocol and, in April 2002, the Renewables Obligation. It was hoped that biomass could replace 2% of coal burnt.[14]

In 1996 and 1997, Thales UK was awarded contracts by Innogy, now Npower, to implement the APMS supervisory and control system on all of the four units, then enabling optimised emissions monitoring and reporting.[14] Between 2005 and 2007 Didcot installed overfire air systems on the four boilers to reduce emissions of nitrous oxide. This ensured compliance with the Large Combustion Plant Directive.

Some ash from Didcot A was used to manufacture building blocks at a factory on the adjacent Milton Park and transported to Thatcham (near Newbury, Berkshire) for the manufacture of Thermalite aerated breeze blocks using both decarbonized fly and raw ash, but most was mixed with water and pumped via a pipeline to former quarries in Radley.

Environmental protests

[edit]

On the morning of Thursday 2 November 2006, 30 Greenpeace trespassers invaded the power station. One group chained themselves to a broken coal-carrying conveyor belt. A second group scaled the 650 ft high chimney, and set up a 'climate camp'. They proceeded to paint "Blair's Legacy" on the side of the chimney overlooking the town. Greenpeace asserted that Didcot Power Station was the second most polluting in Britain after Drax in North Yorkshire,[15] whilst Friends of the Earth describe it as the ninth worst in the UK.[16]

A similar protest occurred early on 26 October 2009, when nine climate change protesters climbed the chimney.[10] Eleven chained themselves to the coal delivery conveyors. The latter group were cut free by police after five hours. The former waited until 28 October before coming down again. All twenty were arrested, and power supplies continued uninterrupted. The power station was installing improved security fencing at the time.[17]

2013 closure

[edit]Didcot A opted out of the Large Combustion Plant Directive which meant it was only allowed to run for up to 20,000 hours after 1 January 2008 and had to close by 31 December 2015 at the latest. The decision was made not to install flue gas desulphurisation equipment which would have allowed continued generation.

Studies did continue into whether there was a possibility that Didcot A might be modernised with new super-clean coal burning capabilities; with RWE partly involved in the study,[18] however in September 2012 RWE Npower announced that Didcot A using its current coal burning capabilities would close at the end of March 2013.[6] On 22 March 2013, Didcot A closed and the de-commissioning process began.[2][3]

In 2007, Didcot was identified as a possible site for a new nuclear power station[19] but, as of August 2019, nothing further had been heard of the proposal.

Demolition

[edit]The three southern cooling towers of Didcot A were demolished by explosives on Sunday 27 July 2014 at 05:01 BST.[20][21]

There had been a campaign to move the time of the demolition to 6 a.m. or later to enable local people to watch the demolition more conveniently,[22] but RWE refused. Despite the early morning demolition, many thousands of people turned out to watch from vantage points, as well as those who watched the towers come down via a live Internet stream. The event trended on Twitter with the hashtag #DidcotDemolition.[23]

The three remaining cooling towers were demolished by explosion early on 18 August 2019.[24] The chimney was demolished at 07:30 GMT on 9 February 2020.[25]

2016 collapse

[edit]On 23 February 2016, a large section of the former boiler house at Didcot A power station collapsed while the building was being prepared for demolition.[26][27] One person was killed outright and three people were listed as missing presumed dead.[28] Four or five people were injured,[26][27] three seriously.[28] Additionally, around 50 people were treated for dust inhalation.[26] The rubble from the collapse was 9 metres (30 ft) high and unstable, which along with the instability of the remaining half of the building hampered search efforts.[28]

The collapse occurred at around 16:00 GMT, and Thames Valley Police declared a "major incident" shortly thereafter. Initial reports of an explosion were ruled out by police after being reported in the media for several hours following the incident.[26][27]

The boiler house was a steel framed building with the boilers suspended from the superstructure and above ground level to allow for their expansion.[13] At the time of the collapse it was being prepared for explosive demolition on 5 March, a process which involved cutting the structure to weaken it.[29]

On 17 July 2016, what remained of the structure was demolished in a controlled explosion by Alford Technologies. The bodies of the three missing men were still in the remains at that time. A spokesman said that due to the instability of the structure, they had been unable to recover the bodies. Robots were used to place the explosive charges due to the danger and the site was demolished just after 6 o'clock in the morning (BST). The families said that they wanted their dead relatives back in one piece, not hundreds of pieces but the demolition company highlighted the inherent danger of rescue operations citing that "legally you could not justify humans going back in."[30]

The search for the missing men continued the day after the controlled demolition. On 31 August 2016, it was confirmed that a body had been found in the rubble and the search had been paused to allow specialist teams to recover the body.[31] On 3 September the body was identified as Christopher Huxtable from Swansea.[32]

On 8 September 2016 police confirmed they had found the body of one of the remaining two missing men.[33] On 9 September, the body was formally identified as that of missing workman Ken Cresswell.[34]

The last missing worker was found on 9 September.[35] He was identified as John Shaw from Rotherham.[36]

In 2018, Coleman and Company who were doing the demolition announced they were stepping down from the demolition, they were replaced by Brown and Mason.

As of February 2024, an investigation by Thames Valley Police and the Health and Safety Executive into the collapse is still "continuing to look at possible corporate manslaughter, gross negligence manslaughter and health and safety offences."[37]

The overarching theme of the Didcot tragedy is delay. Delay in getting the men out and home, delays in gathering evidence, delay in communicating with the families, and now the ultimate insult – an eight-year delay in securing justice and finding out the truth of what caused the collapse. Still, we have no court date.

By July 2024, there had been no further conclusion or updates. In September 2024, Champion wrote to the new Labour policing minister Diana Johnson to complain about the "insulting" delay in concluding the investigation into the collapse and asking Johnson to clarify when the probe might be concluded.[39]

2019 pylon fire

[edit]During the demolition of the three remaining cooling towers on 18 August 2019, debris from one of the collapsing towers hit a nearby pylon, causing it to explode and catch fire. The substation was shut down to allow the fire to burn out without intervention. Several people received minor burns but did not require medical attention. Up to 40,000 homes lost electricity, until power was restored two hours later.

Rail services

[edit]Railways around Didcot | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Like many power stations built at the time, Didcot was served by a rail loop which is a branch from the Great Western Main Line.[40] This allowed weekly coal and oil trains to service the Power Station. Rail facilities included a west-facing inlet connection and an east-facing station outlet connection to the GWML, hopper lines No. 1 and No. 2, and injectors for fly ash on a dust and ash disposal loop.[41] The loop has not been used since the station's closure in 2013.[42]

The track has been partially lifted for construction of a new warehouse on the site of the old coal pits. The coal was first supplied from the Nottingham coalfields, then from South Wales or Avonmouth when the Northern coal pits were closed. The service from South Wales was usually operated by one Class 66 locomotive pulling 25 EWS Coal Cars. The service ran from Avonmouth in Bristol, down the main line, reversing at Didcot Parkway and into the power station.[43] The connections to the main line were severed in mid-2018 in association with the Oxford area remodelling.[44][45]

Technical specifications

[edit]The technical specifications below were correct as at time of commissioning. Later modifications may have changed these.

Turbine

[edit]Manufacturer: C.A. Parsons & Co, Ltd

H.P. cylinder steam:

Inlet 158.6 bar (2,300 lb/sq.in.) at 565 °C

Exhaust 42.0 bar (610 lb/sq.in.) at 365 °C

I.P. cylinder steam:

39.0 bar (565 lb/sq.in) at 565 °C

Condenser Vacuum:

-965 mbar (28.5 Hg)

Generator

[edit]Manufacturer: C.A. Parsons & Co, Ltd

Maximum continuous rating: 500 MW at 23,500 volts

Phase current: Three phases at 14,450 amps each

Efficiency: 98.63%

Stator cooling: Demineralised water

Rotor cooling: Hydrogen

Boiler

[edit]Manufacturer: Babcock & Wilcox Ltd

Maximum continuous rating: 422 kg/s (3,350,000 lb/hr)

Efficiency: 90.76%

Steam at superheater: 165.5 bars (2,400 lb/sq.in.) at 568 °C.

Steam at reheater outlet: 40.3 bars (585 lb/sq.in.) at 568 °C.

Feed water temperature: 256 °C.

Type of firing: Front face, 48 burners

Dimensions of furnace:

29.6 m (97 ft) wide

9.1 m (30 ft) deep

45.7 m (150 ft) high

Circulating water system

[edit]Number of cooling towers: 6

Cooling tower capacity: 11.4 cubic meters per second (150,000 gal/min.) each

Cooling tower dimensions:

Height: 114 m (374 ft)

Diameter: base 91 m (299 ft), top 54 m (176 ft)

Thickness: 0.6m (23 in.) tapering to 0.2m (7 in.)

Total evaporation in six towers: 59 x 103 cubic meters/day (13m gal/day)

Water temperature fall in tower: 10 °C

Condenser water flow: 17.0 cubic meters per second (225,000 gal/min)

Water temperature rise in condenser: 10 °C

Circulating water pump capacity: 18.2 cubic meters per second (240,000 gal/minute)

Make-up water taken from the River Thames (max): 45m gal/day

Water returned to the River Thames: 32m gal/day

Coal plant

[edit]Manufacturer: Babcock-Moxey Ltd.

Train capacity: 1,016 tonnes (1,000 tons), 32.5 tonnes (32 tons) per wagon

Quantity of coal used per day (max): 18,289 tonnes (18,000 tons)

Main chimney

[edit]Dimensions: 199 m (654 ft) high

Base Diameter: 23 m (75 ft)

Number of flues: 4

Gas at exit: 97 km/h (60 mph) at 100 °C.

Motor powers

[edit]Induced draught fan motor: 1,710 kW (2,290 hp)

Forced draught fan motor: 1,200 kW (1,600 hp)

Circulating water pump motor: 6,150 kW (8,250 hp)

Feed pump motor: 6,410 kW (8,600 hp)

Didcot B

[edit]History

[edit]Didcot B is the newer sibling, initially owned by National Power. It was constructed from 1994–1997 by Siemens and National Power's in house project team. It uses a combined cycle gas turbine type power plant to generate up to 1,440 MWe of electricity.[46] It opened in July 1997.

Specification

[edit]It consists of two 680 MWe modules, each with two 230 MW SGT5-4000F[47] (former V94.3A) Siemens gas turbines. It has two heat recovery steam generators, built by International Combustion, since 1997 known as ABB Combustion Services, and a steam turbine.

2014 fire

[edit]On 19 October 2014 just after 8pm, three of the mechanical wooden cooling towers serving one of the steam turbines at Didcot B caught fire. Two of the fifteen fan-assisted cooling towers in the row were completely destroyed, one was seriously damaged, and one suffered light damage.[48] The cause was probably an electrical fault in one of the cooling fans.[49] RWE Npower got half the plant back into operation on 20 October 2014. The other half remained out of action until the four damage cooling towers were repaired. The station returned to full operation in 2015.

Didcot OCGT

[edit]History

[edit]Didcot OCGT is an Open Cycle Gas Turbine that was originally part of Didcot A. Built in 1968, it uses four open-cycle gas turbines, which are each powered by a pair of Rolls-Royce Avon engines to generate 100MW of electricity.[50]

The site was made separate from the Didcot A station as part of the decommissioning process.[51] It was retained to provide a strategic emergency backup for the National Grid, providing a fast-responding source of additional electricity in periods of high demand.[52]

Specification

[edit]Didcot OCGT uses four open cycle gas turbines, which are gas-oil fired. Combustion gases from all four units are combined into a single 101m chimney that has a distinctive blue top.[53]

Ownership

[edit]Following privatisation of the CEGB in the early 1990s, Didcot A passed into the control of what became National Power, who started the construction of Didcot B. Following a de-merger, the plant passed to Innogy plc in 2000. Following the takeover of Innogy by RWE in 2002, ownership passed to RWE npower.[11]

Architectural reception

[edit]

Didcot A won a Civic Trust Award in 1968[13] for how well it blended into the landscape, following its construction. It was voted Britain's third worst eyesore in 2003 by Country Life readers.[54] British poet Kit Wright wrote an "Ode to Didcot Power Station" using a parodic style akin to that of the early romantic poets.[13]

In 1991, Marina Warner made a BBC documentary about the station, describing the cooling towers as having "a sort of incredible furious beauty".[55] Artist Roger Wagner painted Menorah, a crucifixion scene featuring the towers of Didcot power station.[13]

See also

[edit]- List of tallest buildings and structures in Great Britain

- Energy use and conservation in the United Kingdom

- Energy policy of the United Kingdom

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Man who switched Didcot Power Station on and off will miss cooling towers". Oxford Mail. 12 August 2019. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

- ^ a b c Clayton, Indya (16 August 2019). "Send us your photos of Didcot Power Station". Oxford Mail. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

- ^ a b c "Didcot A Power Station switched off after 43 years". BBC News. 22 March 2013. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

- ^ "Didcot Power Station switched off by the man who turned it on". Oxford Mail. 23 March 2013. Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- ^ "Celebrations mark the 40th anniversary of Didcot power station". The Herald. 4 October 2010. Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- ^ a b "Didcot and Fawley power stations to close in March 2013". BBC News. 18 September 2012.

- ^ "Henry Moore's cooling towers under threat". The Independent. 8 November 2012. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- ^ "Disused power station's chimney to be demolished". BBC News. 3 January 2020. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ "Didcot power station 'eyesore'". Oxford Mail. 22 March 2010. Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- ^ a b "Didcot Power Station protester guilty of trespass". BBC News. 13 May 2010. Retrieved 28 July 2014.

- ^ a b "Didcot Power Station celebrates 40th birthday". BBC News. 29 September 2010.

- ^ Sheail, John (1991). Power in Trust. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 180. ISBN 0-19-854673-4.

- ^ a b c d e Historic England. "Didcot A Power Station (1414666)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 22 July 2014.

- ^ a b For more information, see Advanced Plant Management System, the Didcot A Case study on the APMS website or the article about the implementation of the Moore's Quadlog Safety PLC in Didcot Archived 19 October 2006 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Climate campaigners shut down one of UK's biggest power stations". Greenpeace. Archived from the original on 10 August 2008. Retrieved 2 November 2006.

- ^ "Carbon Dinosaurs". Friends of the Earth. Archived from the original on 19 October 2004.

- ^ Sloan, Liam (28 October 2009). "Didcot tower is 'taken'". Oxford Mail.

- ^ "The Role of Coal in Electricity Generation". RWE.

- ^ Little, Reg (25 May 2007). "Nuclear power station could be built in county". The Herald.

- ^ "Didcot power station towers demolished". BBC News. 27 July 2014.

- ^ "Explosives demolish UK power station cooling towers". Reuters. Archived from the original on 8 August 2014.

- ^ McGregor, Sam (30 June 2014). "Hundreds sign petition to change the time of Didcot towers explosion". Oxford Times.

- ^ "Didcot demolition waves goodbye to historic power station towers". The Guardian. 27 July 2014. Retrieved 28 July 2014.

- ^ Ffrench, Andrew (23 July 2019). "Demolition confirmed for three remaining cooling towers at Didcot power station". Oxford Mail. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- ^ "Didcot Power Station's chimney has been demolished". BBC News. 9 February 2020. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- ^ a b c d "Didcot Power Station collapse: One dead and three missing". BBC News. 23 February 2016. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- ^ a b c "Power Station Demolition". Coleman and Company. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016.

- ^ a b c "Three missing after Didcot collapse 'unlikely to be alive'". BBC News. 24 February 2016. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

- ^ Daniel Kemp (2 March 2016). "Mark Coleman: 'This must never happen again'". Construction News. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- ^ "Didcot Power Station: search to resume after demolition". BBC News. 17 July 2016. Retrieved 17 July 2016.

- ^ "Didcot Power Station: Body found in rubble". BBC News. 31 August 2016. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- ^ "Didcot Power Station: Body found in rubble identified". BBC News. 3 September 2016. Retrieved 3 September 2016.

- ^ "Didcot Power Station: Body of missing man found". BBC News. 8 September 2016. Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- ^ "Didcot Power Station: Didcot Power Station body identified as Ken Cresswell". BBC News. 9 September 2016. Retrieved 9 September 2016.

- ^ "Didcot Power Station: Final body in rubble found". BBC News. 9 September 2016. Retrieved 9 September 2016.

- ^ "Guard of honour for John Shaw at Didcot power station". BBC News. 11 September 2016. Retrieved 11 September 2016.

- ^ Zaccaro, Maria; Stenson, Clodagh (23 February 2024). "Didcot Power Station collapse: 'Appalling' wait for answers, MP says". BBC News Online. Retrieved 24 February 2024.

- ^ Weinfass, Ian (22 February 2024). "Didcot Power Station collapse: families and industry await answers eight years on". Construction News. Retrieved 9 July 2024.

- ^ Weinfass, Iain (3 September 2024). "Didcot collapse: MP asks minister to explain 'insulting delay' to probe". Construction News. Retrieved 3 September 2024.

- ^ Bridge, Mike (2010). Trackmaps 3: Western. Bradford-on-Avon: Trackmaps. p. 3C. ISBN 978-0-9549866-6-7.

- ^ Munsey, Myles (2018). Railway Track Diagrams Book 3: Western & Wales. Frome: Trackmaps. pp. 4C. ISBN 9781999627102.

- ^ Munsey, Myles (2018). Railway Track Diagrams Book 3: Western & Wales. Frome: Trackmaps. pp. 4C. ISBN 9781999627102.

- ^ Shannon, Paul (2006). "Southern England". Rail freight since 1968 – Coal. Kettering: Silver Link. p. 38. ISBN 1-85794-263-9.

- ^ Modern Railways, November 2018, p. 75

- ^ "Trackwatch". Modern Railways. Vol. 76, no. 846. March 2019. p. 89.

- ^ RWE. "Didcot B CCGT power plant". RWE. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ "SGT5-4000F". Siemens Power Generation. Archived from the original on 20 August 2008.

- ^ "Major fire at gas-fired Didcot B power station". BBC News. 19 October 2014. Retrieved 19 October 2014.

- ^ "Didcot B power station fire: Electrical fault. Residents of Didcot became concerned about the power supply during the winter if the power station was forced to close". BBC News. 21 October 2014. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ^ "OCGT Fleet". RWE. Archived from the original on 18 April 2019.

- ^ "Didcot OCGT Case Study – Wootton & Wootton". Archived from the original on 19 September 2020.

- ^ "Delivering the balance of power – EBoP". Archived from the original on 30 October 2014.

- ^ "Notice of variation and consolidation with introductory note – The Environmental Permitting (England & Wales) Regulations 2010" (PDF). Environment Agency. RWE Generation UK Plc.

- ^ "Britain's Worst Eyesores". BBC News. 13 November 2003. Retrieved 4 November 2006.

- ^ Race, Michael (16 August 2019). "Didcot: The power station that inspired poetry". BBC News. Retrieved 21 August 2019.