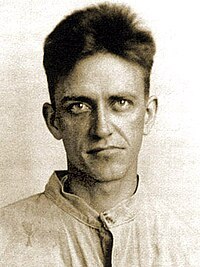

Earl Browder

Earl Browder | |

|---|---|

| |

| Chairman of the Communist Party USA | |

| In office 1934–1945 | |

| Preceded by | William Z. Foster |

| Succeeded by | William Z. Foster |

| General Secretary of the Communist Party USA | |

| In office 1930–1945 | |

| Preceded by | Max Bedacht |

| Succeeded by | Eugene Dennis |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Earl Russell Browder May 20, 1891 Wichita, Kansas, U.S. |

| Died | June 27, 1973 (aged 82) Princeton, New Jersey, U.S. |

| Political party | Socialist Party of America (1907–1920) Syndicalist League of North America (1912–1917) Communist Party USA (1920–1945) |

| Spouse | Raisa Berkman |

| Children | |

| Relatives | |

| Signature | |

Earl Russell Browder (May 20, 1891 – June 27, 1973) was an American politician, spy for the Soviet Union, communist activist and leader of the Communist Party USA (CPUSA). Browder was the General Secretary of the CPUSA during the 1930s and first half of the 1940s. During World War I, Browder served time in federal prison as a conscientious objector to conscription and the war. Upon his release, Browder became an active member of the American Communist movement, soon working as an organizer on behalf of the Communist International and its Red International of Labor Unions in China and the Pacific region.

In 1930, following the removal of a rival political faction from leadership, Browder was made General Secretary of the CPUSA. For the next 15 years thereafter Browder was the most recognizable public figure associated with American communism, authoring dozens of pamphlets and books, making numerous public speeches before sometimes vast audiences, and twice running for President of the United States. Browder also took part in activities on behalf of Soviet intelligence in America during his period of party leadership, placing those who sought to convey sensitive information to the party into contact with Soviet intelligence. In the wake of public outrage over the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, Browder was indicted for passport fraud. He was convicted of two counts early in 1940 and sentenced to four years in prison, remaining free for a time on appeal. In the spring of 1942, the US Supreme Court affirmed the sentence and Browder began what proved to be a 14-month stint in federal prison. Browder was subsequently released by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in May 1942 as a gesture to "promote national unity."

Browder was a staunch adherent of close cooperation between the United States and the Soviet Union during World War II and envisioned continued cooperation between these two military powers in the postwar years. Coming to see the role of American Communists to be that of an organized pressure group within a broad governing coalition, he directed the transformation of the CPUSA into a "Communist Political Association" in 1944; however, following the death of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, a Cold War and internal red scare quickly sprouted up. Browder was expelled from the re-established Communist Party early in 1946, largely due to a refusal to modify these views to accord with changing political realities and their associated ideological demands. Browder lived out the rest of his life in relative obscurity at his home in Yonkers, New York, and later in Princeton, New Jersey, where he died in 1973. He wrote numerous books and pamphlets on political issues.

Background

[edit]Earl Browder was born on May 20, 1891, in Wichita, Kansas, the eighth child of Martha Jane (Hankins) and William Browder, a teacher and farmer.[1] His father was sympathetic to populism.[2]

Career

[edit]

Socialist

[edit]In 1907, Browder, age 16, joined the Socialist Party of America in Wichita and remained in that organization until the party split of 1912, when many of the group's members who supported the syndicalist ideal exited the party after it added an anti-sabotage clause to the party constitution and the recall of National Executive Committeeman William "Big Bill" Haywood.[2] Historian Theodore Draper notes that Browder "was influenced by an offshoot of the syndicalist movement which believed in working in the American Federation of Labor (AFL)."[2] This ideological orientation brought the young Browder into contact with William Z. Foster, founder of an organization called the Syndicalist League of North America which was based upon similar policies and James P. Cannon, an IWW adherent from Kansas.

Browder moved to Kansas City and was employed as an office worker, entering the union of his trade, the Bookkeepers, Stenographers and Accountants union AFL.[2] In 1916, he took a job as manager of the Johnson County Cooperative Association in Olathe, Kansas.[citation needed] Browder was aggressively opposed to World War I and publicly spoke out against it, characterizing the fighting as an imperialist conflict. After the United States joined the war in 1917, Browder was arrested and charged under the Espionage Act conspiring to defeat the operation of the draft law and nonregistration.[3] Browder was sentenced to two years in prison for conspiracy and a year for nonregistration,[3] sitting in jail from December 1917 to November 1918.

Communist

[edit]In 1919, Browder, Cannon and their Kansas City associates started a radical newspaper, The Workers World, with Browder serving as the first editor. However, in June of that year Browder was jailed again on a conspiracy charge, with Cannon taking over as editor.[3] Browder's second prison stint, served at Leavenworth Penitentiary, lasted until November 1920, putting him out of circulation during the critical interval when the Left Wing Section of the Socialist Party quit the SPA to form the Communist Party of America and the Communist Labor Party of America.[3] A series of splits and mergers followed, with the two Communist parties formally merging in 1921. Released from prison at last, Browder lost no time in joining the United Communist Party (UCP), as well as the fledgling Trade Union Educational League (TUEL) being launched by his old associate William Z. Foster. Browder found employment as the managing editor of the monthly magazine of TUEL, The Labor Herald.

In 1920, the Communist International (Comintern) headed by Grigory Zinoviev decided to establish an international confederation of Communist trade unions, the Red International of Labor Unions (RILU, or "Profintern"). A founding convention was planned to be held in Moscow in July 1921 and an American delegation was gathered, including members of the American Communist Parties and the Industrial Workers of the World. Earl Browder was named to this delegation, ostensibly representing Kansas miners, with the non-party man Foster attending as a journalist representing the Federated Press.[4] This trip to Soviet Russia incidentally proved decisive in bringing the syndicalist Foster over to the Communist movement.

Throughout the early 1920s, Browder and Foster worked together closely in the TUEL, trying to win over the support of the Chicago Federation of Labor in the establishment of a new mass Farmer-Labor Party that would be able to challenge the electoral hegemony of the Republican and Democratic parties. In 1928, the estranged Browder and his girlfriend Kitty Harris went to China and lived in Shanghai where Browder served as Secretary of the RILU's Pan-Pacific Trade Union Secretariat, a clandestine labor organization working to unify the labor movement of Asia and the nations of the Pacific basin. The pair returned to the United States in January 1929.[5]

Lovestone

[edit]

The year 1929 marked a major turn in the Communist Party of the United States of America (CPUSA). Party leader Jay Lovestone, having won a massive factional victory over the Chicago-based rival group headed by William Z. Foster at the 6th National Convention of the organization, ran afoul of the Executive Committee of the Communist International (ECCI) and the ultra-radical program which the member organizations of the Comintern were instructed to pursue. Lovestone headed a 10-member delegation to Moscow to appeal his case to the American Commission of ECCI; things did not go well for him and in the squabble over autonomy Lovestone attempted a factional coup involving the seizure of party assets.

On May 17, 1929, ECCI ordered the removal of Lovestone.[5] He was replaced on a provisional basis by a five-person secretariat which included former Lovestone associate Max Bedacht as "Acting Secretary" as well as opposition factional leader and trade union chief Bill Foster; two relatively independent figures in the persons of cartoonist-turned-functionary Robert Minor and former Executive Secretary of the underground party Will Weinstone; and Comintern Representative Boris Mikhailov (pseudonym "G. Williams") as the unpublicized power behind the throne.[5]

While the center of gravity in the leadership of the CPUSA was rapidly shifted, Browder remained largely outside of the ongoing machinations of power, continuing to function as an employee of the Comintern. In August 1929 Browder was dispatched to Vladivostok, located in the far eastern reaches of Soviet Siberia on the Pacific coastline, to attend the final formal gathering of RILU's Pan Pacific Trade Union Secretariat.[5]

Browder returned to the United States again in October 1929, just in time for a critical plenary session of the Central Committee of the American party.[5] Allies in the Comintern had already begun to promote the trusted Browder as the best figure to head the American Communist Party, with Solomon Lozovsky taking up his banner in Moscow while Mikhailov-Williams lent his support from America.[5] Foster's credibility had been badly tarnished in Moscow as a result of his role as a leader of the frequently unprincipled factional war which had paralyzed the American party throughout the decade of the 1920s.[5] Placing Browder — the man responsible for bringing Foster into the communist movement — in authority was seen as a means for shifting power decisively away from the former Lovestone group without opening a new round of factional warfare which would have inevitably resulted had the mantle been given directly to Foster.

Browder deferred from the position of party Secretary, however, not feeling himself sufficiently acclimated to the political situation in the CPUSA.[5] The October plenum therefore returned Bedacht and Minor to a collective leadership, dropping Foster and Weinstone.[5] Weinstone was named as the new American Representative to the Comintern,[6] replacing the recently expelled righthand man of Jay Lovestone, Bertram D. Wolfe, in the position. Browder was added to this new three member Secretariat, named head of the party's Agitation and Propaganda department.[7]

Rise to leadership

[edit]

The 4th quarter of 1929 saw the wheels fall off the wagon, marked by the October 24 Wall Street Crash and the beginning of a massive economic contraction remembered to history as the Great Depression. As head of the CPUSA's Agitprop, Browder was responsible for generating party literature intended to transform the unemployment crisis into a mass movement for revolutionary change.[8] Browder was instrumental in planning American activities relating to International Unemployment Day, March 6, 1930 — an international day of mass protest, set in motion by the Comintern, against unemployment.[8] A network of Unemployed Councils were established under Communist Party auspices.[9]

Another change of the top level leadership of the CPUSA took place at the party's 7th National Convention of June 21–25, 1930.[10] Max Bedacht, formerly a top figure in the hierarchy of the Lovestone faction who had only recanted his views at the 11th hour in front of the American Commission of ECCI in Moscow was removed as Secretary and moved to a less sensitive leadership role as head of the International Workers Order. A new three person Secretariat was appointed, with Browder as Secretary of the political department while Will Weinstone and Bill Foster heading the organizational and trade union departments, respectively.[11] With Weinstone in Moscow as the CPUSA's Comintern Rep and Foster in jail for his connection with the March 6 International Unemployment Day demonstration, which had ended in street fighting in New York City, Browder's position as chief decision-maker of the party was at least temporarily bolstered.[11]

Browder's status as the de facto first among equals among members of the Secretariat of the American CP was further emphasized at the 11th Plenum of the Comintern, held from March 26 to April 11, 1931. There it was Browder who delivered the main report of the CPUSA, indicative of his prime position in the organization.[12] Tension developed between the trio, with Foster seeing his long-desired place as CPUSA chief foiled by a man who had formerly been his lieutenant at the Trade Union Educational League; both the midwesterners distrusted the ambitious, college-educated New Yorker Weinstone.[13] Browder's considerable administrative skills, his ability to intelligently defend his ideas, and his willingness to yield to others when necessary scored points for his personal cause in Moscow.[14]

By the end of 1932 Browder's primary leadership role was consolidated.[14] When Weinstone returned from Moscow anxious to once again pursue party leadership positions, protracted squabbling over party policy threatened to erupt into a 1920s-style factional war.[15] In August the Comintern Representative, sensing such a danger, advised Moscow of "some strong person" to stop the "squabbling".[16] The third member of the Secretariat, William Z. Foster, the party's candidate for president, suffered an attack of angina pectoris and was ordered by doctors to cease campaigning and to undergo bed rest — with visitation and dictation similarly proscribed.[17] With Foster out of the picture and a big majority of the party leadership backing him over Weinstone, Browder appealed to the Comintern to resolve what he called "impossible relations" with Weinstone by assigning one of them for Comintern work abroad.[18]

On November 13, 1932, after extensive debate, the Comintern ruled in Browder's favor, determining that Weinstone would be removed from America to once again serve in Moscow as the CPUSA's official representative there.[18] Moscow's vision seems to have been for a joint party leadership between Browder and Foster.[19] The unexpected factor proved to be the chronic and incapacitating nature of Foster's heart ailment, which left Browder in a position of effective unitary leadership. Although Weinstone had been removed from America to break up an incipient factional war, he continued to campaign for the position of party leader. In the spring of 1933 he obtained the final test of strength he had been looking for, in the form of a dozen meetings of the Comintern's Anglo-American Secretariat in Moscow spread out over 29 days.[20] Throughout April, Browder and Weinstone leveled charges and counter-charges against one another, examining the Communist Party's activities in the United States in fine detail.[21] Despite significant criticism of certain of his actions, Browder emerged from the Moscow sessions in a firm position of authority. Weinstone, accepting defeat at last, remained in Moscow as the CPUSA's CI Rep until 1934.[22]

Popular front leader

[edit]

While Earl Browder was one of the top leaders of American communism during the so-called Third Period of the early 1930s, he came into his own during the interval which followed, the era of the popular front against fascism. With the rise of Adolf Hitler to Chancellor of Germany at the end of January 1933, the balance of power in Europe was shifted. Formerly home to one of the most powerful communist organizations, the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) was quickly suppressed. The failure of the KPD to cooperate with workers adhering to the rival Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) was seen by many Comintern officials as a major contributing factor to the disaster. New tactics building a broad alliance in opposition to fascism seemed to be indicated.

Browder was an enthusiastic supporter of this new party line. By the middle of 1934 the Browder-led Central Committee of the CPUSA was pushing the leaders of its youth section, the Young Communist League, to establish a working alliance with the youth section of the rival Socialist Party, the Young People's Socialist League.[23] In the same vein, Browder himself picked up hints from Socialist Party leader Norman Thomas that joint work between Socialists and Communists might be possible on specific issues, in reply to which Browder issued a letter formally proposing a large scale united front of the two organizations.[23]

Still perceiving President Franklin D. Roosevelt as a fascist dictator in the making, Browder and the Communists began to examine their political isolation from the American working class and to envision the establishment of a new labor party which would include both Communists and Socialists within its ranks.[24] In December 1934 Browder won Comintern approval for his scheme, arguing his case in person in Moscow.[25] Browder returned to the United States at the end of the month, revealing his plan to a surprised party membership in a public speech delivered on January 6, 1935.[25] The Socialist Party, for its part, remained skeptical, having been on the receiving end of more than a decade's worth of vilification and violence.

In conjunction with its newly found interest in building bridges with non-communist progressives, the CPUSA launched potent new mass organizations such as the American League Against War and Fascism (September 1933), the American Youth Congress (1935), and the League of American Writers (April 1935). Moreover, as the 1930s progressed and the New Deal policies of the Roosevelt administration became established, the Browder-led Communist Party moved from a position of bitter opposition to critical support.

After 1935 the Communist Party maintained only nominal opposition to the Roosevelt administration, with Browder heading the party's 1936 ticket as its candidate for president in the election of 1936. He received 80,195 votes. In practice, progressives of both parties were seen as key constituents in a broad "People's Front" against fascism and a bulwark of the movement for collective security in Europe against German aggression. The Communist Party attenuated its message of the historical inevitability of revolution, emphasizing progressive trends in American history and attempting to cast itself as an indigenous reform movement under the slogan "Communism is 20th Century Americanism".[26] The stark phraseology of Marxism, based upon the inevitability of class struggle, was replaced by a fuzzy critique of capitalism using Rooseveltian terms like "economic royalism".[26]

Browder was not only the leading party decision-maker but also the public face of this effort. He was, one historian later noted, a man who "paid lip service to 'proletarian internationalism'" and who "knew better than to oppose Soviet-imposed policies, however inappropriate they might be for American conditions", but who "wanted to be a leader of a national movement with power and influence of its own."[27] The "Communism is 20th Century Americanism" campaign, during which Communism was portrayed as an integral part of the American democratic tradition, was successful in building the size and scope of the party organization. But with this growth came a correlated expansion of Browder's personal ego.[28] A cult of personality began to be nurtured among the party faithful in miniature reflection of the systemic adulation of Joseph Stalin in the USSR. In the words of Maurice Isserman: "The constant praise of his colleagues and the party press, and the adulation in which the membership held him (among his papers Browder saved a letter from a Seattle Communist addressed to the 'Greatest of Living Americans, Earl Browder'), transformed the once unassuming apparatchik of the 1920s into an arrogant and uncompromising party dictator."[29]

Browder's chief rival in the Communist Party leadership in this interval was William Z. Foster. When a new recession struck in 1937, stifling tax revenue, President Roosevelt and Congress responded by cutting funding for its signature Works Progress Administration by 50 percent in an attempt to help bring the budget into balance.[30] Foster sought for the CPUSA to renew a militant stance against capitalism and the government in response to the economic downturn.[30] Browder, on the other hand, pushed the party towards moderate criticism of the administration, urging increased expenditures on public works and unemployment relief and lauding Roosevelt's move away from isolationism in foreign policy in the wake of the rising tide of fascism in Europe.[31] A short-lived revival of the Farmer-Labor Party idea was scrapped under Browder's direction, and the New Deal coalition endorsed as the practical base upon which a People's Front could be constructed.[30] Over question of Foster's militance versus Browder's accommodation with New Deal realities, the Comintern ruled decisively in favor of Browder.[32]

Browder made his final trip to the USSR in October 1938, where he made arrangements with Comintern chief Georgi Dimitrov to establish shortwave radio communications in the event that international conflict made direct communication impossible.[33] No communications of this sort were made until late in September 1939, when the CPUSA's political line on the dramatically changed European situation would be specified.[34]

Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact

[edit]

European geopolitics were fundamentally altered on August 23, 1939, when the Foreign Ministers of the USSR and Nazi Germany formally signed a mutual non-aggression treaty known to history as the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact. The agreement included secret protocols providing for the Nazi invasion and division of Poland. Germany's September 1 invasion of Poland brought an immediate response from its treaty partners France and United Kingdom, who declared war on Germany on September 3. World War II had begun.

The Soviet Union invaded Eastern Poland on September 17, occupying land that otherwise would have been taken over by Germany.[35] The Soviet government went further, however, by signing a joint statement with the Germans characterizing the partition of Poland as a fait accompli, calling for an end to hostilities, and placing the onus for any escalation of the European conflict on the governments of Great Britain and France.[35]

Virtually overnight the political lines of the communist parties of the world shifted. Those who were formerly the greatest cheerleaders for collective security against the danger of Germany now became staunch opponents of American intervention in the European military situation—reflective of the newly revised needs of Soviet foreign policy. All anti-fascist propaganda was immediately terminated, overt criticism of German action was minimized, the culpability of the governments of France and Britain was exaggerated.[35] Browder's CPUSA claimed that Hitler's foes intended to escalate the ongoing European conflict into a counterrevolutionary offensive against the USSR.[35]

The result of the sudden shift of the party line caused shock and confusion among many members of the Communist Party USA, a good number of whom had joined during the period of the Popular Front against fascism.[36] Browder declared at one Philadelphia rally that only "a dozen or so" had left the CPUSA over the change of line; but this was simply untrue. On the contrary, the party's ranks fell by 15% between 1939 and 1940, and recruitment of new members in 1940 fell by 75% from 1938 levels.[36] The public image of the USSR as a main bulwark against fascism and claims of the CPUSA as an indigenous radical organization were severely undermined.[37]

Moreover, the CPUSA's new propaganda offensive against United States participation in the so-called "Imperialist War" brought it into political conflict with the Roosevelt administration, which had begun to question the wisdom of isolationism. In the summer of 1939, Texas Congressman Martin Dies, Jr. (D), chairman of the House Special Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC), learned that the U.S. Department of Justice had begun to investigate old charges that Earl Browder had traveled abroad under assumed names, making use of false documents, during the 1920s.[38] Dies proceeded to subpoena Browder to appear before the committee to give testimony on the matter.[38] On September 5, 1939, days after the German invasion of Poland, Browder appeared before HUAC, providing exhaustive testimony over the course of two days.[39]

Midway through the first day of testimony, Browder was asked in passing whether he had ever traveled abroad under a false passport. Before party attorney Joseph Brodsky could stop him, Browder answered, "I have."[38] Although he subsequently refused to answer follow-up questions about the matter, citing the protection against self-incrimination offered by the Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution, the damage caused by Browder's admission under oath had been done.[38] Conservative politicians such as Congressman J. Parnell Thomas (R) of New Jersey attempted to make political capital out of Browder's admission, by intimating that the Roosevelt administration had coddled the country's leading Communist. Parnell Thomas maintained that Browder was "swaggering [and] apparently untouchable" despite being Stalin's "number one stooge in this country."[40]

With popular feeling against Communism raging in the wake of European events and political heat rising in Washington, the Justice Department moved to action. On October 23 a federal grand jury in Manhattan indicted Browder for passport fraud, a felony.[41] The formal charge against him specified that Browder had made multiple returns to the United States using a passport bearing his own name, but which had been obtained on the basis of a falsely sworn statement.[41] Indictments of CPUSA treasurer William Wiener and Young Communist League leader Harry Gannes on passport charges followed in December, and the Communist Party sent several of its top leaders into hiding in anticipation of a broader crackdown.[42]

On January 17, 1940, Browder's trial for passport fraud began at federal court in New York City.[43] Browder faced a two-count indictment, upon which conviction would have carried a maximum sentence of 10 years in prison and a $4,000 fine.[44] Owing to expiration of the statute of limitations on earlier passport offenses, the government was able to prosecute Browder solely for his passport use during the years 1937 and 1938.[44] To aid dramatic effect, recently convicted Soviet spy Nicholas Dozenberg was placed on the stand to identify Browder's photograph on papers obtained in Dozenberg's name.[45] After the court refused a long series of motions by Browder's attorney, G. Gordon Battle, Browder took control of his own defense in the courtroom. He reminded jurors that the trial did not concern false documents from the distant past and proclaimed that the actual charges against him were based upon a "web of technicalities".[46]

Jury deliberations in the Browder case lasted less than an hour, with a guilty verdict returned.[47] Browder was sentenced to 4 years in prison and a $2,000 fine — a result less than the maximum but in excess of sentences given to others in similar circumstances.[47] The conviction was unanimously affirmed on appeal on June 24, 1940, and the United States Supreme Court concurred on February 17, 1941.[48] On March 25, 1941, Browder surrendered to US Marshals, who transported him by rail to the Atlanta Federal Penitentiary.[49] Two days later, with his face masked behind a pillowcase to hinder photographers, Browder was led into the penitentiary to begin serving his four-year term.[50] He would not emerge again for 14 months.

World War II

[edit]While Browder was imprisoned, the war continued, with major events in Europe and the Pacific. On June 22, 1941, some 3.9 million Axis troops, led by Nazi Germany, launched Operation Barbarossa, a massive and bloody invasion of the Soviet Union. Immediately the political line of the entire world communist movement shifted from one of anti-intervention in the so-called "imperialist war" to one of intense advocacy for anti-fascist intervention; the slogan was "Defend the Soviet Union".[51] On July 12 the governments of Great Britain and the USSR exchanged pledges of mutual aid, setting the stage for military cooperation between the capitalist nations of the West and their historic Bolshevik foe.[52]

On December 7, 1941, the air force of Imperial Japan launched a sudden and devastating attack upon the American naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. A German declaration of war on the United States followed,[citation needed] and direct American participation in the Second World War was begun. The interests of the American government, the Soviet government, and the American Communist Party became aligned. In the Atlanta prison, treatment of Browder was relaxed, and he began to be allowed regular visits from acting CPUSA leader Robert Minor.[53] The Communist Party had previously conducted a "Free Earl Browder" campaign on behalf of its jailed leader but with little success, owing to bitter public sentiment over the USSR's pact with Nazi Germany and the CPUSA's kowtowing to Moscow's policy shift. By early 1942, however the party's pleas on behalf of Browder began to gain traction among government officials.[54]

On May 16, 1942, just prior to a visit to the United States by Vyacheslav Molotov, Foreign Minister of the USSR, President Roosevelt decided to remove a minor impediment to the closest possible wartime relations between the two powers by commuting Browder's sentence to time served.[54] In a statement to the press, the Roosevelt administration said that Browder's early release would "have a tendency to promote national unity and allay any feeling...that the unusually long sentence in Browder's case was by way of penalty upon him because of his political views."[55]

Browder discreetly returned to New York City, where he resumed his place as General Secretary of the Communist Party, USA. Throughout the early years of the war, the CPUSA agitated for the establishment of a second military front in Europe to alleviate pressure exerted by Axis forces upon the Soviets in the east. The Communists proved to be enthusiastic supporters of the war effort, and the party press worked to mobilize public sentiment by printing accounts of Nazi atrocities in Germany and abroad.[56] Browder directed Communist Party members to concentrate upon "problems of a centralized war economy and production for the war", using their place in the labor movement to help ameliorate labor discord.[57]

Browder did not personally devise the wartime policies of the CPUSA; the main elements of party policy, such as advocacy of an immediate second front, opposition to strikes, an end to racial discrimination in job hiring, and total support of Roosevelt's internal policy initiatives, were already well established by the time of his release in May 1942.[58] Nevertheless, Browder became the public spokesman for these policies, and published a book in the fall of 1942, called Victory and After, which was frank in promoting class collaboration as essential to the cause of victory.[58]

Browder postulated that the cooperation between America and the Soviet Union would continue into the postwar period.[58] A victory of the "United Nations" would "make possible the solution of reconstruction problems with a minimum of social disorder and civil violence in the various countries most concerned."[59] This belief in longterm cooperation between the Allied powers abroad and civil peace at home were the hallmarks of what was later known as "Browderism".

By the end of 1943 the tide of the war in Europe had shifted, and there was no doubt either about the survival of the USSR or the ultimate outcome of the Second World War.[60] With the Red Army moving inexorably westward, the possibility of a Communist Europe seemed within reach to the party faithful.[60] Cooperation between the United States, Great Britain, and the Soviet Union was at its zenith following the conclusion of the Tehran Conference, held November 28 to December 1, 1943.

On January 7, 1944, the 28 members of the governing National Committee of the CPUSA were called into session in New York City.[61] Although they usually conducted their business in closed executive session, the members of the National Committee were surprised to learn that their session was to be held in a large room in front of about 200 invited guests.[61] In his keynote report to the gathering, General Secretary Browder revisited the close cooperation indicated at the Tehran Conference and declared that "Capitalism and Socialism have begun to find their way to peaceful coexistence and collaboration in the same world."[62]

The Communist Party was advancing its policy initiatives through political cooperation with New Deal supporters, Browder indicated, and he declared that "Communist organization in the United States should adjust its name to correspond more exactly to the American political tradition and its own practical political role."[63] Consequently, the name of the Communist Party USA would be changed to the "Communist Political Association", Browder noted — advising those gathered of a decision which had already been made by the Political Bureau of the party.[64] The speakers following Browder lent individual support to the predetermined change of party name and shift in conception of the organization's role in the American political firmament.[64]

The National Committee voted unanimously in support of Browder's proposals. They established committees to draft a new constitution for the organization and to prepare for a May 1944 convention to ratify the changes.[65] Factional opposition to Browder's change took the form of a letter to the party leadership by Browder's nemesis William Z. Foster and Foster's friend, Philadelphia District Organizer Sam Darcy, signed only by the former.[66] The pair disagreed with Browder's view that the bourgeoisie would continue its wartime coordination with the Roosevelt administration after the war, and predicted a breakdown that would require an aggressive response by American Communists.[67]

Browder allowed the Foster-Darcy letter to be circulated only to a handful of top party leaders, who at a February 1944 meeting of the Politburo voted to reject the letter.[68] Foster's objection was muted when Browder emphasized that open criticism would have been regarded as a punishable breach of party discipline.[69] Darcy refused to submit to party discipline on this matter, however, viewing it as a matter of fundamental principle. He was subsequently expelled from the CPA by a committee headed by Foster himself.[68]

Expulsion

[edit]With the end of the great power alliance at the end of World War II and the beginning of the Cold War, so-called "Browderism" was attacked by the rest of the international Communist movement. They particularly criticized the restructuring of the American party in 1944. In April 1945 the French Communist Party's theoretical magazine, Les Cahiers du communisme, published an article by French party leader Jacques Duclos that declared that Browder's beliefs about a harmonious post-war world were "erroneous conclusions in no wise flowing from a Marxist analysis of the situation."[70] Duclos held that Browder's "liquidation of the independent political party of the working class" constituted a "notorious revision of Marxism".[70]

American communists realized that the Duclos letter was initiated by Moscow, which had been largely out of contact since it had liquidated the Comintern in 1943 as its own gesture to wartime harmony. Duclos otherwise had no reason to criticize the activity of a fraternal party, American Communists maintained.[71] Moreover, Duclos quoted directly from the Foster-Darcy letter — a document known to only a handful of top American party leaders, with a copy dispatched to Moscow.[71]

An interview with Gil Green by Anders Stephanson was published in the 1993 anthology New Studies in the Politics and Culture of U.S. Communism, edited by Michael F. Brown, Randy Martin, Frank Rosengarten, and George Snedeker. This exchange was included:

AS: But in 1945 Browder went out as a result of Duclos' attack on his coalition line. GG: I was terribly shocked by the article. But in my naiveté and innocence, I was shocked because I was supposed to have been involved in what was a betrayal of Marxism. This was undoubtedly coming from Moscow, and had greater significance than an article by some leader of the French party who suddenly attacks the line of the American party without even letting us know his views beforehand. According to the Italians, later on, there is evidence that it was not aimed so much at Browder and the party here as at the Italian and French parties. The fear was that, with their underground fighting against the Nazis, they would emerge with tremendous prestige and be able to take an independent course. And while the blow was struck against us here, it wasn't necessarily concerned with us alone.[72]

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, historians Harvey Klehr, John Earl Haynes and Kyrill Anderson discovered a letter in the Soviet archives showing that the "Duclos Letter" had actually been written in Russian and published in Moscow in early 1945, while the war with Germany was still in progress. The timing of the original showed that the USSR had already decided post-war relations with the US would not be friendly. The Russian-language original was translated into French and given to Duclos after the Japanese surrender, with instructions for him to publish it under his own name.[73]

The American communists quickly reversed Browder's political line, stripping him of executive power in June 1945 and reconstituting itself as the Communist Party of the United States of America at a snap convention held in July.[71] Predictably, Bill Foster, elevated in stature by being quoted in the "Duclos letter", led the opposition to Browder and "Browderism". He was named to replace "the man from Kansas" as party chairman in 1945. Eugene Dennis, an individual held in high esteem by Moscow, was named Browder's successor to the more important position of General Secretary.[74]

In January 1946, Browder began publishing a mimeographed weekly newsletter of economic analysis called Distributors Guide: Economic Analysis: A Service for Policy Makers.[75] The subscription price was hefty—$100 per year; he wanted to gain a readership among business executives and political decision-makers.[75] Browder produced a total of 16 issues, each based on his vision of Soviet-American cooperation, as opposed to the unfolding Cold War between the powers.[75] The Communist Party regarded his independent publication as further evidence of a serious breach of party discipline. On February 5, 1946, Earl Browder was expelled from the CPUSA.[76]

Literary agent

[edit]Browder applied for a visa to travel to Moscow to appeal his expulsion, but he was forced to wait two months for its approval.[77] In the meantime he continued to issue his Distributors Guide, which became explicitly more pro-Stalin and pro-Soviet in later issues.[77] With his visa finally approved, Browder ended publication of his newsletter at the end of April 1946. The former American party leader departed for the Soviet Union to determine whether his expulsion could be overturned.[77] Browder arrived in Moscow on May 3 and met with old friends, including Solomon Lozovsky, former head of the Profintern, as well as Stalin's right-hand man, Viacheslav Molotov.[78]

Molotov was unable to intercede on Browder's behalf to reintegrate him into an American Communist Party. By then its leaders regarded him as an undisciplined opportunist and unreliable leader. However, his past service was rewarded with an appointment as "American Representative of the State Publishing House" for publication of Soviet books in the United States.[79] Upon his return, Browder registered with the United States Department of Justice as a foreign agent, as required by law. He acted as a sort of literary agent for the Soviet government, receiving English translations of various books and articles and attempting to gain placement for them with American publishers.[80] While generally unsuccessful at gaining such publication, Browder met monthly with the second secretary of the Soviet Embassy in Washington, D.C. He provided him with written memoranda on the situation in the United States in general and the Communist Party of the United States of America, in particular — effectively providing analysis on behalf of Soviet intelligence.[80]

In April 1950, Browder was called to testify before a Senate Committee investigating communist activity. Questioned by Joseph McCarthy (R-Wis), Browder openly criticized the American Communist Party but refused to answer questions that would incriminate former comrades. He also claimed under oath that he had never been involved in espionage activities.[81] Browder was charged with contempt of Congress but Judge F. Dickinson Letts ordered his acquittal, ruling that the committee had not acted legally. Browder was never prosecuted for his perjury before the committee nor for his spying on behalf of the Soviet Union.

In March 1950, Browder shared a platform with Max Shachtman, the dissident Trotskyist, in which the pair debated socialism. Browder defended the Soviet Union while Shachtman acted as a prosecutor. Reportedly at one point in the debate, Shachtman listed a series of leaders of various Communist parties and noted that each had died at the hands of Stalin. At the end of this speech, he noted that Browder, too, had been a leader of a Communist Party and, pointing at him, said: "There-there but for an accident of geography, stands a corpse!"[82]

Following the Twentieth Party Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in 1956, a period in which some within the American Communist Party briefly sought to exert its independence from Moscow, another effort was made to reintegrate Browder into the CPUSA. This effort at liberalization was soon defeated, however. Although remaining committed to the cause of socialism, Browder never belonged to the Communist Party again.[citation needed]

Espionage

[edit]On June 2, 1957, Browder appeared on the television program The Mike Wallace Interview, where he was grilled for 30 minutes about his past in the Communist Party. Host Mike Wallace quoted Browder as having recently said, "Getting thrown out of the Communist Party was the best thing that ever happened to me."[83] When asked to elaborate, Browder replied: "That's right. I meant that the Communist Party and the whole communist movement was changing its character, and in 1945, when I was kicked out, the parting of the ways had come, and if I hadn't been kicked out I would have had the difficult task of disengaging myself from a movement that I could no longer agree with and no longer help."[83]

"I was involved in no conspiracies", Browder adamantly declared to Wallace and his television audience.[83] Browder repeatedly connected Jacob Golos, a longtime Communist Party activist and Soviet agent, with CPUSA members who had offered to share sensitive information that they thought the party should know.[84] While initially most of these would-be informants were employees of private industry, party members who were employees of the federal government were later also brought into Golos' circle of contacts.[85] Browder was also periodically given access to important information by Golos before its transmission to his superiors in Moscow.[86]

Browder's public protestations against accusations of spying were contradicted by the 1995 release of the Venona documents. This secretly decoded material confirmed that Browder was engaged in recruiting potential espionage agents for Soviet intelligence during the 1940s.[87] In 1938, Rudy Baker (Venona code name: SON) had been appointed to head the CPUSA underground apparatus to replace J. Peters, after the defection of Whittaker Chambers, allegedly at the request of Browder (Venona code name: FATHER).[citation needed] According to self-confessed NKVD recruiter Louis Budenz, he and Browder participated in discussions with Soviet intelligence officials to plan the assassination of Leon Trotsky.[88]

While in federal custody in the US, Browder never revealed his status as an agent recruiter. He was never prosecuted for espionage. Venona decrypt #588 April 29, 1944, from the KGB New York office states, "for more than a year Zubilin (station chief) and I tried to get in touch with Victor Perlo and Charles Flato. For some reason Browder did not come to the meeting and just decided to put Bentley in touch with the whole group. All occupy responsible positions in Washington, D.C."[89] Soviet intelligence thought highly of Browder's recruitment work: in a 1946 OGPU memorandum, Browder was personally credited with hiring eighteen intelligence agents for the Soviet Union.[citation needed]

Members of Browder's family were also involved in work for Soviet intelligence. According to a 1938 letter from Browder to Georgi Dimitrov, then General Secretary of the Comintern, Browder's younger sister Marguerite was an agent working in various European countries for the NKVD. (The letter was found in the Comintern archives after the fall of the Soviet Union.)[90] Browder expressed concern over the effect on the American public if his sister's secret work for Soviet intelligence were to be exposed: "In view of my increasing involvement in national political affairs and growing connections in Washington political circles ... it might become dangerous to this political work if hostile circles in America should obtain knowledge of my sister's work." He requested she be released from her European duties and returned to America to serve "in other fields of activity". Dimitrov forwarded Browder's request to Nikolai Yezhov, then head of the NKVD, requesting Marguerite Browder's transfer.[91] Browder's half-niece, Helen Lowry (aka Elza Akhmerova, also Elsa Akhmerova), worked with Iskhak Akhmerov, a Soviet NKVD espionage controller, from 1936 to 1939 under the code name ADA(?) ADA was Kitty Harris (later changed to ELZA)). In 1939, Helen Lowry married Akhmerov. Lowry was named by Soviet intelligence agent Elizabeth Bentley as one of her contacts. Lowry, Akhmerov and their actions on behalf of Soviet intelligence are referred to in several Venona project decryptions as well as Soviet KGB archives.[citation needed]

Personal life and death

[edit]Browder married Raisa Berkman.[92] He died in Princeton, New Jersey on June 27, 1973.[93] His three sons, Felix, William, and Andrew, all distinguished research mathematicians, have been leaders in the American mathematical community.[citation needed]

Grandchild Bill Browder (son of Felix) was co-founder and head of the investment group Hermitage Capital Management, which operated for more than 10 years in Moscow during a wave of privatization after the fall of the Soviet Union. Browder became a British citizen in 1998. Great-grandchild Joshua Browder is a British-American entrepreneur, consumer rights activist, and public figure.[citation needed]

Works

[edit]- Books and pamphlets

- A System of Accounts for a Small Consumers' Co-operative New York: Cooperative League of America, 1918.

- Unemployment: Why it Occurs and How to Fight It. Chicago: Literature Dept., Workers Party of America, 1924.

- Class Struggle vs. Class Collaboration. Chicago: Workers Party of America, 1925.

- Civil War in Nationalist China. Chicago: Labor Unity Publishing Association, 1927. alternate link

- China and American Imperialist Policy. Chicago: Labor Unity Pub. Association, 1927.

- Out of a Job New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1930.

- War Against Workers' Russia! New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1931.

- Secret Hoover-Laval War Pacts. New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1931.

- The Fight for Bread: Keynote Speech. New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1932.

- The Meaning of Social-Fascism: Its Historical and Theoretical Background. New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1933.

- What Every Worker Should Know About the NRA. New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1933.

- Is Planning Possible Under Capitalism? New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1933.

- What is the New Deal? New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1933.

- Report of the Central Committee to the Eighth Convention of the Communist Party of the USA, Held in Cleveland, Ohio, April 2–8, 1934. New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1934.

- The Communist Party and the Emancipation of the Negro People. New York: Harlem section of the Communist Party, 1934.

- Communism in the United States. New York: International Publishers, 1935.

- Unemployment Insurance: The Burning Issue of the Day. New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1935.

- New Steps in the United Front: Report on the Seventh World Congress of the Communist International[permanent dead link]. New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1935.

- Religion and Communism. New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1935.

- Security for Wall Street or for the Masses. Philadelphia: Communist Party of the USA, 1935.

- The People's Front in America. New York: Published for the State Campaign Committee of the Communist Party by Workers Library Publishers, 1936.

- Report of the Central Committee to the Ninth National Convention of the Communist Party of the USA. New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1936.

- Democracy or Fascism? Earl Browder's Report to the Ninth Convention of the Communist Party. New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1936.

- Zionism: Address at the Hippodrome Meeting Jun 8, 1936. New York: Yidburo Publishers, 1936.

- Foreign Policy and the Maintenance of Peace: Radio Speech of Earl Browder, Communist Party candidate for U.S. President, Delivered over a Coast-to-Coast Network of the National Broadcasting Company, August 28, 1936. New York: Communist Party of USA, 1936.

- Lincoln and the Communists. New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1936.

- Who are the Americans? New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1936.

- To all Sympathizers of the Communist Party. New York: Communist Party, 1936.

- The Landon-Hearst Threat Against Labor: A Labor-Day Message. New York: National Campaign Committee Communist Party, 1936.

- Old Age Pensions and Unemployment Insurance: Radio Address. New York: National Campaign Committee Communist Party, 1936.

- Hearst's "Secret" Documents in Full. New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1936.

- Acceptance Speeches: Communist Candidates in the Presidential Elections. New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1936.

- The Communist Position in 1936: Radio Speech Broadcast March 5, 1936. New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1936.

- Build the United People's Front: Report to the November Plenum of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the USA. New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1936.

- The Results of the Elections and the People's Front: Report Delivered December 4, 1936 to the Plenum of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the USA. New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1936.

- What Is Communism? New York: Vanguard Press, 1936.

- Trotskyism Against World Peace. New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1937.

- Talks to America. New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1937.

- Lenin and Spain New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1937. alternate link

- North America and the Soviet Union: The Heritage of Our People. New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1937.

- The 18th Anniversary of the Founding of the Communist Party: Radio Address Delivered over a Coast-to-Coast Network of the National Radio Broadcasting Company, September 1, 1937. New York: Central Committee Communist Party, 1937.

- The Communists in the People's Front: Report Delivered to the Plenary Meeting of the Central Committee of the Communist Party, USA held June 17-20, 1937. New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1937.

- China and the USA. New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1937.

- New Steps to Win the War in Spain. (with Bill Lawrence) New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1938.

- Social and National Security. New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1938.

- The Nazi Pogrom, an Outcome of the Munich Betrayal. New York, N.Y., State Committee, Communist Party, 1938.

- Unite the People of Illinois for Jobs, Security, Peace and Democracy: Report to the Illinois State Convention of the Communist Party. Chicago: Illinois State Committee of the Communist Party, 1938.

- Attitude of the Communist Party on the Subject of Public Order. [Detroit, MI]: Chevrolet Branch of the Communist Party, 1938.

- Report to the Tenth National Convention of the Communist Party on Behalf of the Central Committee. New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1938.

- The Democratic Front for Jobs, Security, Democracy, and Peace: Report to the Tenth National Convention of the Communist Party of the USA on Behalf of the National Committee, Delivered on Saturday, May 28, 1938, at Carnegie Hall, New York. New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1938.

- Traitors in American History: Lessons of the Moscow Trials. New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1938.

- A Message to Catholics. New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1938.

- The People's Front. New York: International Publishers, 1938. — A collection of speeches and articles.

- Concerted action or isolation: which is the road to peace? New York: International Publishers, 1938.

- The Economics of Communism: The Soviet Economy in its World Relation[permanent dead link]. New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1939.

- Religion and Communism. New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1939

- The 1940 Elections: How the People Can Win. New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1939.

- Theory as a Guide to Action. New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1939.

- Unity for Peace and Democracy. New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1939.

- Whose War is It? New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1939.

- Socialism, War, and America. New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1939.

- Stop the War New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1939.

- Finding the Road to Peace: Radio Address, Aug. 29, 1939. New York: Communist Party, 1939.

- America and the Second Imperialist War. New York, New York State Committee, Communist Party, 1939.

- Communist Leader Says: "Protect Bill of Rights to Keep America Out of War." San Francisco: Communist Party, 1939.

- Remarks of the General Secretary of the Communist Party, Earl Browder, Made at the Enlarged Meeting of the State Committee of the Communist Party of California on May 28, 1939. Los Angeles: California Organization and Educational Departments, Communist Party USA, 1939.

- Speech of Earl Browder, Auspices of Yale Peace Council, New Haven, Conn., Nov. 28, 1939. New York: Communist Party of America, National Committee, Publicity Dept., 1939.

- The People's Road to Peace. New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1940. —Keynote address to 11th Convention.

- The People against the War-Makers. New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1940.

- The Jewish People and the War. New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1940.

- Internationalism; Results of the 1940 Election: Two Reports. New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1940.

- Earl Browder Takes His Case to the People. New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1940.

- An American Foreign Policy for Peace. New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1940.

- Earl Browder Talks to the Senators on the Real Meaning of the Voorhis "Blacklist" Bill. New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1940.

- The Most Peculiar Election: The Campaign Speeches of Earl Browder. New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1940.

- Study Guide and Outline for the People's Front. New York: Educational and Literature Departments, New York State Committee, Communist Party, 1940.

- A Letter from Earl Browder. New York City : Communist Party of U.S.A., 1940.

- A Message from Earl Browder to the Youth of America. New York: National Election Campaign Committee, Youth Division, 1940.

- United Front against Fascism and War: How to Achieve It! A Serious Word to the Socialist Party. New York City: New York District Committee, Communist Party of USA, 1940.

- The New Moment in the Struggle against War. New York City: New York State Committee, Communist Party U.S.A., 1940.

- Mr. Browder Goes to Washington.[New York, N.Y.]: Browder for Congress Campaign Committee, 1940.

- The Communists on Education and the War. New York : Young Communist League, 1940.

- A Message to California Educators: Some Inner Contradictions in Washington's Imperialist Foreign Policy. Calif. : The Committee, 1940.

- The Message They Tried to Stop! The Most Peculiar Election Campaign in the History of the Republic: Speech Delivered by Electrical Transcription at Olympic Auditorium, Los Angeles, California, September 8 and at San Francisco, California, September 11, 1940. New York: National Election Campaign Committee, Communist Party USA, 1940.

- The Second Imperialist War. New York: International Publishers, 1940.

- The Way Out. New York: International Publishers, 1940.

- The Communist Party of the USA: Its History, Role and Organization. New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1941.

- Communism and Culture New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1941.

- Earl Browder Says. New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1941.

- The Way Out of the Imperialist War. New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1941.

- The Road to Victory. New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1941.

- A Different Kind of Party: Earl Browder Tells How the Communist Party is Distinguished from All Other Parties [n.c.: n.p., 1941.

- Victory—and after. New York: International Publishers, 1942.

- Production for Victory. New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1942.

- Victory Must Be Won: Independence Day Speech, Madison Square Garden, July 2, 1942. New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1942.

- Earl Browder on the Soviet Union. New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1942.

- The Economics of All-Out War. New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1942.

- One Year Since Pearl Harbor. New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1942.

- When Do we Fight? New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1942.

- 2nd Front Now! This is the Will of the People. San Francisco: Issued by California Communist Party, 1942.

- Free the Anti-Fascist Prisoners in North Africa: Address. New York: Communist Party, U.S.A., 1942.

- The Future of the Anglo-Soviet-American Coalition. New York: Workers Library Publishers 1943.

- George Dimitroff. New York: International Publishers, 1943.

- Policy for Victory. New York: Workers Library Publishers 1943.

- Wage Policy in War Production. New York: Workers Library Publishers 1943.

- Make 1943 the Decisive Year. New York: Workers Library Publishers 1943.

- The Mine Strike and Its Lessons. New York City: New York State Committee, Communist Party, 1943.

- A Conspiracy Against our Soviet Ally: A Menace to America. Chicago: Illinois State Committee of the Communist Party, 1943.

- A Talk About the Communist Party. New York: Workers Library Publishers 1943.

- Hitler's Secret Weapon: The Bogey of Communism. San Francisco: California Communist Party, 1943.

- Browder Hits Anti-Soviet Plot speech of Earl Browder, at Aperion Manor, Brooklyn, NY, April 1, 1943. Baltimore? : Communist Party and Young Communist League of Baltimore?, 1943.

- A Lincoln's Birthday Message to You. New York: Communist Party?, 1944.

- The meaning of the elections New York: Workers Library Publishers 1944.

- Moscow, Cairo, Teheran. New York: Workers Library Publishers 1944.

- Economic Problems of the War and Peace. New York: Workers Library Publishers 1944.

- The Road Ahead to Victory and Lasting Peace. New York: Workers Library Publishers 1944.

- Teheran: Our Path in War and Peace. New York: International Publishers, 1944.

- Teheran and America: Perspectives and Tasks. New York: Workers Library Publishers 1944.

- Shall the Communist Party Change Its Name? New York: Workers Library Publishers 1944.

- America's Decisive Battle. New York, N.Y: New Century, 1945

- Why America is interested in the Chinese Communists New York, N.Y: New Century, 1945

- The press and America's future New York, N.Y: Daily Worker, 1945

- Browder's Speech to National Committee. San Francisco: California State Committee CPA, 1945.

- Appeal of Earl Browder to the National Committee CPUSA Against the Decision of the National Board of February 5, 1946 for His Expulsion. Yonkers: Earl Browder, 1946

- The Writings and Speeches of Earl Browder: From May 24, 1945 to July 26, 1945. Yonkers, NY: Earl Browder, 1947.

- War or Peace with Russia? New York: A.A. Wyn, 1947.

- Soviet book news, literature, art, science. New York: 1947.

- The Decline of the Left Wing of American Labor. Yonkers, NY: [Earl Browder], 1948.

- Answer to Vronsky. New York? : n.p., 1948.

- Labor and Socialism in America. Yonkers, NY: Earl Browder, 1948.

- The "Miracle" of Nov. 2nd: Some Aspects of the American Elections New York? : n.p., 1948.

- World Communism and US Foreign Policy: A Comparison of Marxist Strategy and Tactics: After World War I and World War II. New York: Earl Browder, 1948.

- "Americus" [pseudonym], Where Do We Go From Here? An Examination of the Record of the 14th National Convention, CPUSA. n.c.: Earl Browder, 1948.

- "Americus", Parties, issues, and Candidates in the 1948 Elections: Brief Review and Analysis. Yonkers, NY: Earl Browder, 1948.

- The Coming Economic Crisis in America New York? : n.p., 1949

- More about the economic crisis New York? : s.n., 1949

- War, peace and socialism, New York? : s.n., 1949

- U.S.A. & U.S.S.R.: their relative strength S.l. : s.n., 1949

- How to halt crisis and war: an economic program for progressives S.l. : s.n., 1949

- Chinese Lessons for American Marxists. n.c. Yonkers, NY: Earl Browder, 1949.

- In defense of communism: against W.Z. Foster's "new route to socialism. Yonkers, NY: s.n., 1949.

- Keynes, Foster and Marx. Yonkers, N.Y 1950

- Earl Browder before U.S. Senate: the record and some conclusions. Yonkers, N.Y 1950

- "Is Russia a socialist community?": affirmative presentation in a public debate Yonkers, N.Y: The author 1950

- Language & war : letter to a friend concerning Stalin's article on linguistics Yonkers, N.Y: The author 1950

- Modern resurrections & miracles Yonkers, N.Y: Earl Browder, 1950

- Toward an American peace policy Yonkers, N.Y: The author 1950

- "Should Soviet China be admitted to the United Nations?" debate. s.l. : s.n., 1951

- The meaning of MacArthur: letter to a friend s.l. : s.n., 1951

- Contempt of Congress; the trial of Earl Browder. Yonkers, N.Y: E. Browder 1951

- Four letters concerning peaceful co-existence of capitalism and socialism: together with speech of June 2, 1945 on the same question Yonkers, N.Y. : Issued for private circulation only by E. Browder, 1952

- Should America be returned to the Indians? Yonkers, N.Y. : The author, 1952

- A postscript to the discussion of peaceful co-existence Yonkers, N.Y: E. Browder 1952

- Marx and America: A Study in the Doctrine of Impoverishment. New York: Duell, Sloan and Pearce, 1958.

- Socialism in America Yonkers, N.Y.: Browder, 1960.

- Articles and introductions

- Andrés Nin Struggle of the Trade Unions Against Fascism. (Introduction) Chicago: The Trade Union Educational League, 1923. (Labor Herald Library #8) alternate link

- Solomon Lozovsky The World's Trade Union Movement (Introduction) Chicago: The Trade Union Educational League, 1924. (Labor Herald Library #10)

- Trade Unions in America (with James Cannon and William Z. Foster) Chicago: Published for the Trade Union Educational League by the Daily Worker 1925 (Little Red Library #1)

- “Official Communications: Letter of the P.P.T.U.S. to the Latin American Trade Union Congress, Montevideo, Uruguay”. The Pan-Pacific Monthly, no. 26, February 14, 1929.

- “The Agrarian Problem in China”. The Pan-Pacific Monthly, no. 26, May 1929.

- Technocracy and Marxism (with William Z. Foster and Vyacheslav Molotov) New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1933.

- Karl Marx, 1883–1933 (with Max Bedacht and Sam Don) New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1933.

- How do we raise the question of a labor party? (with Jack Stachel) New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1935.

- Debate: Which Road for American Workers — Socialist or Communist? with Norman Thomas, New York: Socialist Call, 1936.

- Organize mass struggle for social insurance: tasks of the American Communist Party in organizing struggle for social insurance (with Sergei Ivanovich Gusev) New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1933.

- The meaning of the Palestine partition (with John Arnold). New York, N.Y. State Jewish Buro, Communist Party, 1937.

- Red baiting: enemy of labor; with a letter to Homer Martin by Earl Browder by Louis Budenz New York : Workers Library Publishers, 1937

- The Constitution of the United States: with the amendments; also, the Declaration of Independence New York: International Publishers, 1937.

- The Path of Browder and Foster. (with others) New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1941.

- A discussion of people's war policies: Vice President Henry Wallace's May 8, 1942 speech, Asst. Secretary of State Sumner Welles' May 30, 1942 speech, Earl Browder's June 7, 1942 article in "The Worker", the Atlantic Charter. New York : Workers School, 1942.

- Speed the second front (with others) New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1942.

- Anti-semitism: what it means and how to combat it (with William Gallacher) New York: Workers Library Publishers 1943.

- Is communism a menace? A debate between Earl Browder and George E. Sokolsky. New York: New masses 1943.

- Choose between Teheran and Hitler: extracts from the report by Earl Browder to the National Convention of the U.S.A. Communist Party, May 20, 1944. Sydney: Central Committee of the Australian Communist Party, 1944.

- The heritage of Jefferson[permanent dead link] (with Claude Bowers and Francis Franklin) New York : Workers School, 1943.

- Jew-baiting is cannibalism (with William Gallacher) Sydney: Current Book Distribution, 1944.

- Communists and national unity: an interview of PM with Earl Browder. with Harold Lavine New York: Workers Library Publishers 1944.

- On the dissolution of the Communist Party of the United States by Jacques Duclos San Francisco, Calif. : State Committee, Communist Political Association of California, 1945 (foreword)

- Browder's position on the resolution (with William Z. Foster) in "Discussion Bulletin No. 1". San Francisco: California State Committee CPA, 1945.

- "Speech to the CPA National Committee – June 18, 1945", in "Discussion Bulletin No. 9". San Francisco: California State Committee, CPA, July 1945; pp. 1–3, 6, 8.

- How can Soviet Russia and the United States keep the peace? (with Theodore Granik and George Sokolsky) Washington, D.C.: Ransdell, 1946

- Communists in the struggle for Negro rights (with James Ford, Benjamin Davis and William Patterson) New York, N.Y: New Century, 1945

- Is Russia a Socialist Community? The Verbatim Text of a Debate. March 1950 debate with Max Shachtman moderated by C. Wright Mills. The New International: A Monthly Organ of Revolutionary Marxism, Vol.16 No.3, May–June 1950, pp. 145–176.

- Contempt of Congress : the trial of Earl Browder Yonkers, N.Y. : Earl Browder, [1951]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Earl Browder Papers an inventory of his papers at Syracuse University". Archived from the original on October 11, 2020. Retrieved October 20, 2016.

- ^ a b c d Theodore Draper, The Roots of American Communism, pg. 308

- ^ a b c d Theodore Draper, The Roots of American Communism, pg. 309

- ^ Theodore Draper, The Roots of American Communism, pg. 316

- ^ a b c d e f g h i James G. Ryan, Earl Browder: The Failure of American Communism. Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press, 1997; pg. 37.

- ^ Ryan, Earl Browder, pp. 37–38.

- ^ Ryan, Earl Browder, pg. 38.

- ^ a b Ryan, Earl Browder, pg. 40.

- ^ Ryan, Earl Browder, pg. 41.

- ^ Ryan, Earl Browder, pp. 45–46.

- ^ a b Ryan, Earl Browder, pg. 46.

- ^ Harvey Klehr, The Heyday of American Communism: The Depression Decade. New York: Basic Books, 1984; pg. 25.

- ^ Ryan, Earl Browder, pg. 47.

- ^ a b Ryan, Earl Browder, pg. 49.

- ^ Ryan, Earl Browder, pg. 52.

- ^ Quoted in Ryan, Earl Browder, pg. 53.

- ^ Ryan, Earl Browder, pg. 53.

- ^ a b Ryan, Earl Browder, pg. 54.

- ^ Ryan, Earl Browder, pg. 55.

- ^ Ryan, Earl Browder, pg. 58.

- ^ Ryan, Earl Browder, pp. 59–60.

- ^ Ryan, Earl Browder, pg. 59.

- ^ a b Ryan, Earl Browder, pg. 76.

- ^ Ryan, Earl Browder, pp. 77–78.

- ^ a b Ryan, Earl Browder, pg. 78.

- ^ a b Maurice Isserman, Which Side Were You On? The American Communist Party During the Second World War. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1982; pg. 9.

- ^ Isserman, Which Side Were You On? pp. 8–9.

- ^ Isserman, Which Side Were You On? pg. 14.

- ^ Isserman, Which Side Were You On? pp. 14–15.

- ^ a b c Ryan, Earl Browder, pg. 129.

- ^ Ryan, Earl Browder, pp. 128–129.

- ^ Ryan, Earl Browder, pp. 130–131.

- ^ Isserman, Which Side Were You On? pg. 46.

- ^ Isserman, Which Side Were You On? pp. 46–47.

- ^ a b c d Fraser Ottanelli, The Communist Party of the United States: From the Depression to World War II. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1991; pg. 197.

- ^ a b Ottanelli, The Communist Party of the United States, pg. 198.

- ^ Ottanelli, The Communist Party of the United States. pp. 198–199.

- ^ a b c d Isserman, Which Side Were You On? pg. 48.

- ^ See: House Special Committee on Un-American Activities, Investigation of Un-American Propaganda Activities in the United States: Hearings Before a Special Committee on Un-American Activities, House of Representatives, Seventy-Sixth Congress, First Session...: Volume 7, September 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 11, 12, and 13, 1939, at Washington, DC. Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1940; pp. 4275–4520.

- ^ Ryan, Earl Browder, pp. 174–175.

- ^ a b Ryan, Earl Browder, pp. 175.

- ^ Isserman, Which Side Were You On? pp. 49–50.

- ^ Isserman, Which Side Were You On? pg. 55.

- ^ a b Ryan, Earl Browder, pg. 179.

- ^ Ryan, Earl Browder, pg. 180.

- ^ Ryan, Earl Browder, pg. 181.

- ^ a b Ryan, Earl Browder, pg. 182.

- ^ Ryan, Earl Browder, pp. 182–183.

- ^ Ryan, Earl Browder, pg. 192.

- ^ Isserman, Which Side Were You On? pp. 85–86.

- ^ Isserman, Which Side Were You On? pg. 103.

- ^ Isserman, Which Side Were You On? pg. 108.

- ^ Isserman, Which Side Were You On? pp. 130–131.

- ^ a b Isserman, Which Side Were You On? pg. 131.

- ^ Quoted in Isserman, Which Side Were You On? pg. 131.

- ^ Isserman, Which Side Were You On? pp. 132–133.

- ^ The Daily Worker, December 16, 1942, pp. 5–6. Quoted in Isserman, Which Side Were You On? pp. 134–135.

- ^ a b c Isserman, Which Side Were You On? pg. 145.

- ^ Earl Browder, Victory and After. New York: International Publishers, 1942; pg. 113. Quoted in Isserman, Which Side Were You On? pp. 145–146.

- ^ a b Isserman, Which Side Were You On? pg. 187.

- ^ a b Isserman, Which Side Were You On? pg. 188.

- ^ Quoted in Isserman, Which Side Were You On? pg. 188.

- ^ Quoted in Isserman, Which Side Were You On? pg. 190.

- ^ a b Isserman, Which Side Were You On? pg. 190.

- ^ Isserman, Which Side Were You On? pg. 191.

- ^ Harvey Klehr, John Earl Haynes, and Kirill M. Anderson, The Soviet World of American Communism. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1998; pg. 93.

- ^ Klehr, Haynes, and Anderson, The Soviet World of American Communism, pp. 93–94.

- ^ a b Klehr, Haynes, and Anderson, The Soviet World of American Communism, pg. 94.

- ^ Isserman, Which Side Were You On? pp. 192–193.

- ^ a b Quoted in Klehr, Haynes, and Anderson, The Soviet World of American Communism, pg. 95.

- ^ a b c Klehr, Haynes, and Anderson, The Soviet World of American Communism, pg. 95.

- ^ Stephanson, Anders, and Gil Green. "Interview with Gil Green". Ed. Michael E. Brown, Randy Martin, and George Snedeker. Comp. Frank Rosengarten. New Studies in the Politics and Culture of U.S. Communism. New York: Monthly Review, 1993. 307-26. Print.

- ^ Klehr, Harvey, Haynes, John Earl and Anderson, Kyrill M. The Soviet World of American Communism. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998.)

- ^ Klehr, Haynes, and Anderson, The Soviet World of American Communism, pg. 96.

- ^ a b c Philip J. Jaffe, The Rise and Fall of American Communism. New York: Horizon Press, 1975; pg. 138.

- ^ Jaffe, The Rise and Fall of American Communism, pg. 139.

- ^ a b c Jaffe, The Rise and Fall of American Communism, pg. 140.

- ^ Jaffe, The Rise and Fall of American Communism, pp. 140–141.

- ^ Jaffe, The Rise and Fall of American Communism, pp. 141-142.

- ^ a b Jaffe, The Rise and Fall of American Communism, pg. 142.

- ^ James G. Ryan, Socialist Triumph as a Family Value: Earl Browder and Soviet Espionage, American Communist History, 1, no. 2 (December 2002).

- ^ Is Russia a Socialist Community? The Verbatim Text of a Debate. Archived November 22, 2005, at the Wayback Machine, Marxists website, March 1950

- ^ a b c "The Mike Wallace Interview. Guest: Earl Browder" Archived December 20, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, June 2, 1957. Retrieved October 14, 2009.

- ^ Kathryn S. Olmsted, Red Spy Queen: A Biography of Elizabeth Bentley. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2002; p. 22.

- ^ Olmsted, Red Spy Queen, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Olmsted, Red Spy Queen, p. 43.

- ^ Haynes, John Earl, and Klehr, Harvey, Venona: Decoding Soviet Espionage in America. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2000; pg. ???.

- ^ Affidavit of Louis Budenz, 11 November 1950, American Aspects of the Assassination of Leon Trotsky, U.S. Congress, House of Representatives, Committee on Un-American Activities, 81st Cong., 2d sess., part I, v–ix.

- ^ "Elizabeth Bentley reports on new KGB recruits from American Communist Party" Archived 2012-03-30 at the Wayback Machine, Venona 588 New York to Moscow, 29 April 1944, National Security Agency

- ^ Klehr, Haynes, and Firsov, Secret World of American Communism 241

- ^ Klehr, Haynes, and Firsov Secret World of American Communism 243

- ^ "Inside Bill Browder's War Against Putin". Vanity Fair. November 11, 2018. Archived from the original on January 24, 2022. Retrieved February 9, 2022.

- ^ Whitman, Alden (June 28, 1973). "Earl Browder, Ex-Communist Leader, Dies at 82". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 3, 2022. Retrieved September 2, 2022.

Further reading

[edit]- Contemporary material

- Citizens's Committee to Free Earl Browder, A Comparative Study of the Earl Browder and Other Passport Cases. New York: n.d. [1941?].

- Citizens's Committee to Free Earl Browder, The Browder case: a summary of facts: a brief for justice and fair play in America New York: Citizens' Committee to Free Earl Browder, 1941

- Citizens's Committee to Free Earl Browder, The Campaign to free Earl Browder: A Report. New York: The Committee, 1942.

- Communist Party of the United States of America Material for discussion leaders on the fight against Browderism.

- Duclos, Jacques. "On the Dissolution of the Communist Party of the United States". First published in Cahiers du Communisme, April 1945. Reprinted in William Z. Foster et al., Marxism–Leninism vs. Revisionism.. New York: New Century Publishers, Feb. 1946; pp. 21–35.

- Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, Earl Browder: the man from Kansas New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1941.

- William Z. Foster, On the struggle against revisionism New York : National Veterans Committee of the Communist Party 1956

- William Z. Foster; Jaques Duclos; Eugne Dennis; and John Williamson, Marxism–Leninism vs. Revisionism New York: New Century Publishers, 1946.

- John Gates, On Guard against Browderism, Titoism, Trotskyism[permanent dead link]. New York: New Century Publishers, 1951.

- Gill Green, Browder's "coalition" – with monopoly capital [S.l. : Communist Party of the United States of America?, 1949.

- House Special Committee on Un-American Activities, Investigation of Un-American Propaganda Activities in the United States: Hearings Before a Special Committee on Un-American Activities, House of Representatives, Seventy-Sixth Congress, First Session...: Volume 7, September 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 11, 12, and 13, 1939, at Washington, DC. Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1940; pp. 4275–4520.

- Robert G. Thompson, The path of a renegade : why Earl Browder was expelled from the Communist Party New York: New Century Publishers, 1946.

- Robert Thompson, The Convention Unanimously Rejects Browder's Appeal. New York: New Century Publishers, 1948.

- "Congress: Children of Moscow". Time, September 18, 1939.

- Secondary sources

- John Earl Haynes, "Russian Archival Identification of Real Names Behind Cover Names in VENONA". Cryptology and the Cold War, Center for Cryptologic History Symposium, October 27, 2005.

- John Earl Haynes and Harvey Klehr, Venona: Decoding Soviet Espionage in America. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000.

- Harvey Klehr, John Earl Haynes, and Fridrikh Igorevich Firsov, The Secret World of American Communism. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995.