Early social changes under Islam

| Part of a series on |

| Islamic studies |

|---|

| Jurisprudence |

| Science in medieval times |

|

|

| Arts |

|

|

| Other topics |

| Islamization of knowledge |

Many social changes took place under Islam between 610 and 661, including the period of Muhammad's mission and the rule of his immediate successor(s) who established the Rashidun Caliphate.

A number of historians stated that changes in areas such as social security, family structure, slavery and the rights of women improved on what was present in existing Arab society.[1][2][3][4][5][6] For example, according to Bernard Lewis, Islam "from the first denounced aristocratic privilege, rejected hierarchy, and adopted a formula of the career open to the talents".[1][7]

Bernard Lewis believes that the advent of Islam was a revolution which only partially succeeded due to tensions between the new religion and very old societies that the Muslims conquered. He thinks that one such area of tension was a consequence of what he sees as the egalitarian nature of Islamic doctrine. Islam denounced aristocratic privilege, rejected hierarchy, and adopted a formula of the career open to the talents.[1]

Constitution of Medina

[edit]The Constitution of Medina, also known as the Charter of Medina, was drafted by Muhammad in 622. It constituted a formal agreement between Muhammad and all of the significant tribes and families of Yathrib (later known as Medina), including Muslims, Jews, and pagans.[8][9] The document was drawn up with the explicit concern of bringing to an end the bitter intertribal fighting between the clans of the Aws (Banu Aus) and Banu Khazraj within Medina. To this effect it instituted a number of rights and responsibilities for the Muslim, Jewish, and pagan communities of Medina bringing them within the fold of one community-the Ummah.[10]

The precise dating of the Constitution of Medina remains debated but generally scholars agree it was written shortly after the hijra (622).[11] It effectively established the first Islamic state. The Constitution established: the security of the community, religious freedoms, the role of Medina as a sacred place (barring all violence and weapons), the security of women, stable tribal relations within Medina, a tax system for supporting the community in time of conflict, parameters for exogenous political alliances, a system for granting protection of individuals, a judicial system for resolving disputes, and also regulated the paying of blood-wite (the payment between families or tribes for the slaying of an individual in lieu of lex talionis).

Social changes

[edit]Practices

[edit]John Esposito sees Muhammad as a reformer who condemned practices of the pagan Arabs such as female infanticide, exploitation of the poor, usury, murder, false contracts, fornication, adultery, and theft.[12] He states that Muhammad's "insistence that each person was personally accountable not to tribal customary law but to an overriding divine law shook the very foundations of Arabian society... Muhammad proclaimed a sweeping program of religious and social reform that affected religious belief and practices, business contracts and practices, male-female and family relations".[13] Esposito holds that the Qur'an's reforms consist of "regulations or moral guidance that limit or redefine rather than prohibit or replace existing practices." He cites slavery and women's status as two examples.

According to some scholars, Muhammad's condemnation of infanticide was the key aspect of his attempts to raise the status of women.[6] A much-cited verse the Qur'an that addresses this practice is: "When the sun shall be darkened when the stars shall be thrown down when the mountains shall be set moving when the pregnant camels shall be neglected when the savage beasts shall be mustered when the seas shall be set boiling, when the souls shall be coupled, when the buried infant (mawudatu) shall be asked for what sin she was slain when the scrolls shall be unrolled..."[Quran 81:1],[6] though a hadith[14] links the term used to the pull-out method.

The true prevalence of gendercide in this time period is uncertain. Donna Lee Bowen writes in Encyclopaedia of the Qur'an that it was "common enough among the pre-Islamic Arabs to be assigned a specific term, waʾd"[15] Some historians believe it was once common, but had been in steep decline in the decades leading up to Islam,[16] while others believe it occurred with some regularity as a means of birth control among destitute families both before and after Islam.[17]

Though the belief that pre-Islamic Arabs regularly practised female infanticide has become common among both Muslims and Western writers, few surviving sources are referencing the practice before Islam. An inscription in Yemen forbidding the practice, dating to approximately 400 BC, is the sole mention of it in pre-Islamic records. However there's lack of information about that period so nothing can be said with certainty. [18] Among ṣaḥīḥ Muslim sources, there are some individual named as having partaken in, observed, or intervened in cases of infanticide, such as Zayd ibn Amr, as stated in a hadith narrated by Asma bint Ab.[19]

Social security

[edit]William Montgomery Watt states that Muhammad was both a social and moral reformer. He asserts that Muhammad created a "new system of social security and a new family structure, both of which were a vast improvement on what went before. By taking what was best in the morality of the nomad and adapting it for settled communities, he established a religious and social framework for the life of many races of men."[20]

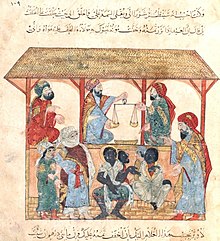

Slavery

[edit]

The Qur'an makes numerous references to slavery ([Quran 2:178], [Quran 16:75], [Quran 30:28]), regulating[clarification needed] but thereby also implicitly accepting this already existing institution. Lewis states that Islam brought two major changes to ancient slavery which were to have far-reaching consequences. "One of these was the presumption of freedom; the other, the ban on the enslavement of free persons except in strictly defined circumstances," Lewis continues. The position of the Arabian slave was "enormously improved": the Arabian slave "was now no longer merely a chattel but was also a human being with a certain religious and hence a social status and with certain quasi-legal rights."[21]

Lewis states that in Muslim lands slaves had a certain legal status and had obligations as well as rights to the slave owner, an improvement over slavery in the ancient world.[21][22] Due to these reforms the practice of slavery in the Islamic Empire represented a "vast improvement on that inherited from antiquity, from Rome, and from Byzantium."[21]

Although there are many common features between the institution of slavery in the Qur'an and that of neighbouring cultures, however, the Qur'anic institution had some unique new features.[23] According to Jonathan Brockopp, professor of History and Religious Studies, the idea of using alms for the manumission of slaves appears to be unique to the Qur'an (assuming the traditional interpretation of verses [Quran 2:177] and [Quran 9:60]). Similarly, the practise of freeing slaves in atonement for certain sins[which?] appears to be introduced by the Qur'an.[23] Brockopp adds that: "Other cultures limit a master's right to harm a slave but few exhort masters to treat their slaves kindly, and the placement of slaves in the same category as other weak members of society who deserve protection is unknown outside the Qur'an. The unique contribution of the Qur'an, then, is to be found in its emphasis on the place of slaves in society and society's responsibility toward the slave, perhaps the most progressive legislation on slavery in its time."[23]

Women's rights

[edit]To evaluate the effect of Islam on the status of women, many writers have discussed the status of women in pre-Islamic Arabia, and their findings have been mixed.[24] Some writers have argued that women before Islam were more liberated, drawing most often on the first marriage of Muhammad and that of Muhammad's parents, but also on other points such as worship of female idols at Mecca.[24] Other writers, on the contrary, have argued that women's status in pre-Islamic Arabia was poor, citing practices of female infanticide, unlimited polygyny, patrilineal marriage and others.[24]

Valentine Moghadam analyzes the situation of women from a Marxist theoretical framework and argues that the position of women is mostly influenced by the extent of urbanization, industrialization, polarization and political ploys of the state managers rather than culture or intrinsic properties of Islam; Islam, Moghadam argues, is neither more nor less patriarchal than other world religions especially Buddhism, Hinduism, Christianity, and Judaism.[25][26]

Majid Khadduri writes that under the Arabian pre-Islamic law of status, women had virtually no rights, whereas Sharia (Islamic law) provided women with several rights.[27] John Esposito states that the reforms affected[how?] marriage, divorce, and inheritance.[12] According to Karen Armstrong, there were cultures, in the West and elsewhere, where women were not accorded the rights of inheritance and divorce until centuries later.[28] The Oxford Dictionary of Islam states that the general improvement of the status of Arab women included the prohibition of female infanticide, and recognizing women's full personhood.[29] Gerhard Endress states: "The social system ... build up a new system of marriage, family and inheritance; this system treated women as an individual too and guaranteed social security to her as well as to her children. Legally controlled polygamy was an important advance on the various loosely defined arrangements which had previously been both possible and current; it was only by this provision (backed up by severe punishment for adultery), that the family, the core of any sedentary society could be placed on a firm footing."[30]

Leila Ahmed argues that the independence and financial success of Muhammad's first wife Khadijah, including "her economic independence, her initiating of her marriage, and not even needing a male guardian to act as an intermediary (as was to be required by Islam), her marriage to a man many years younger than herself, and her remaining with him in a monogamous marriage (Muhammad had no other wife until after her death), all from pre-Islamic era."[7]

However, other records state that in pre-Islamic Arabia inheritance and status of women in pre-Islamic Arabia was not secured, but was limited to upper classes.

Marriage

[edit]According to Islamic sources, no limitations were set on men's rights to marry or to obtain a divorce in pre-Islamic tradition.[27] Islamic law, however, restricted polygamy to four wives at one time, not including concubines.([Quran 4:3])[12] The institution of marriage, characterized by unquestioned male superiority in the pre-Islamic law of status, was redefined and changed into one in which the woman was somewhat of an interested partner. 'For example, the dowry, previously regarded as a bride-price paid to the father, became a nuptial gift retained by the wife as part of her personal property'[12][27] Under Islamic law, marriage was no longer viewed as a "status" but rather as a "contract". The essential elements of the marriage contract were now an offer by the man, an acceptance by the woman, and the performance of such conditions as the payment of dowry. The woman's consent was imperative, either by active consent or silence.[31] Furthermore, the offer and acceptance had to be made in the presence of at least two witnesses.[12][27][29] According to a hadith collected by Al-Tirmidhi, "And indeed I order you to be good to the women, for they are but captives with you over whom you have no power than that, except if they come with manifest Fahishah (evil behaviour). If they do that, then abandon their beds and beat them with a beating that is not harmful. And if they obey you then you have no cause against them. Indeed you have rights over your women, and your women have rights over you. As for your rights over your women, then they must not allow anyone whom you dislike to treat on your bedding (furniture), nor to admit anyone in your home that you dislike. And their rights over you are that you treat them well in clothing them and feeding them."[32]

Inheritance and wealth

[edit]John Esposito states that "women were given inheritance rights in a patriarchal society that had previously restricted inheritance to male relatives."[12] Similarly, Annemarie Schimmel wrote that "Compared to the pre-Islamic position of women, Islamic legislation meant an enormous progress; the woman has the right, at least according to the letter of the law, to administer the wealth she has brought into the family or has earned by her own work."[33] Leila Ahmed argues that examples of women inheriting from male relatives in pre-Islamic Mecca and other Arabian trade cities are recorded in Islamic sources. However, its practice varied between tribes and was uncertain.[7]

According to The Oxford Dictionary of Islam, women were also granted the right to live in the matrimonial home and receive financial maintenance during marriage and a waiting period following the death and divorce.[29]

The status of women

[edit]Watt states that Islam is still, in many ways, a man's religion. However, he states that Muhammad, in the historical context of his time, can be seen as a figure who testified on behalf of women's rights and improved things considerably. Watt explains the historical context surrounding women's rights at the time of Muhammad: "It appears that in some parts of Arabia, notably in Mecca, a matrilineal system was in the process of being replaced by a patrilineal one at the time of Muhammad. Growing prosperity caused by a shifting of trade routes was accompanied by a growth in individualism. Men were amassing considerable personal wealth and wanted to be sure that this would be inherited by their actual sons, and not simply by an extended family of their sisters' sons." Muhammad, however, by "instituting rights of property ownership, inheritance, education and divorce, gave women certain basic safeguards".[34]

While the art historian Jonathan Bloom believes that the Qur'an does not require women to wear veils, stating that instead, it was a social habit picked up with the expansion of Islam,[35] the vast majority of Islamic scholars disagree,[36] interpreting the Qur'anic verses 24:31[Quran 24:31] and 33:59[Quran 33:59] as requiring female modest dress, including a veil covering the head.

Haddad and Esposito state that "although Islam is often criticized for the low status it has ascribed to women, many scholars believe that it was primarily the interpretation of jurists, local traditions, and social trends which brought about a decline in the status of Muslim women. In this view, Muhammad granted women rights and privileges in the sphere of family life, marriage, education, and economic endeavours, rights that help improve women's status in society." However, "the Arab Bedouins were dedicated to custom and tradition and resisted changes brought by the new religion." Haddad and Esposito state that in this view "the inequality of Muslim women happened because of the preexisting habits of the people among whom Islam took root. The economics of these early Muslim societies were not favourable to a comfortable life for women. More important, during Islam's second and third centuries the interpretation of the Qur'an was in the hands of deeply conservative scholars, whose decisions are not easy to challenge today."[37]

Others argue that this perspective is based solely on Islamic records of pre-Islamic Arabs, written centuries after Islam's emergence, and that pre-Islamic Arabs were less misogynistic than the above view gives them credit for.[38] Many scholars view the monodimensional depiction of pre-Islamic Arabia as an intentional choice on the part of Islamic scholars, who sought to present the era as deeply regressive in order to present Islam as tolerant by comparison.[38] The Moroccan scholar Fatima Mernissi argues that this trend has worsened in the modern era, as "modern Arab histories refuse to admit, even at the level of pure analysis, that customs expressing female sexual self-determination" existed in pre-Islamic Arabia and were subsequently outlawed in Islamic times. However she also argues that these weren't caused by Islam itself rather it was influence of patriarchal culture of the people who developed Islamic law, she believes Islam in itself is neutral in regards to women's rights.[39] [7]

Under the customary tribal law existing in Pre-Islamic Arabia women, as a general rule, had virtually no legal status; fathers sold their daughters into marriage for a price, women had little or no property or succession rights. Upper-class women usually had more rights than tribal women and might own property or even inherit from relatives.[40]

Children

[edit]The Qur'an rejected the pre-Islamic idea of children as their fathers' property and abolished the pre-Islamic custom of adoption.[41]

A. Giladi holds that Quran's rejection of the idea of children as their fathers' property was a Judeo-Christian influence and was a response to the challenge of structural changes in tribal society.[41]

The Quran also replaced the pre-Islamic custom of adoption (assimilation of an adopted child into another family in a legal sense) by the recommendation that believers treat children of unknown origin as "their brothers in the faith and clients".[42] Adoption was viewed "as a lie, as an artificial tie between adults and children, devoid of any real emotional relationship, as a cause of confusion where lineage was concerned and thus a possible source of problems regarding marriage between members of the same family and regarding inheritance. But a child that was not born into a family can still be raised by a foster family but the child must retain his identities, such as his last name and lineage. The prophet has stated that a person who assists and aids an orphan, is on the same footing in heaven to the prophet himself."[41]

Sociological changes

[edit]Sociologist Robert N. Bellah (Beyond Belief) argues that Islam in its 7th-century origins was, for its time and place, "remarkably modern...in the high degree of commitment, involvement, and participation expected from the rank-and-file members of the community". This because, he argues, that Islam emphasized the equality of all Muslims. Leadership positions were open to all. However, there were restraints on the early Muslim community that kept it from exemplifying these principles, primarily from the "stagnant localisms" of tribe and kinship. Dale Eickelman writes that Bellah suggests "the early Islamic community placed a particular value on individuals, as opposed to collective or group responsibility".[43]

The Islamic idea of community (that of ummah), established by Muhammad, is flexible in social, religious, and political terms and includes a diversity of Muslims who share a general sense of common cause and consensus concerning beliefs and individual and communal actions.[44]

Moral changes

[edit]Muslims believe that Muhammad, like other prophets in Islam, was sent by God to remind human beings of their moral responsibility, and challenge those ideas in society which opposed submission to God. According to Kelsay, this challenge was directed against these main characteristics of pre-Islamic Arabia:[45]

- The division of Arabs into varying tribes (based upon blood and kinship). This categorization was confronted by the ideal of a unified community based upon taqwa (Islamic piety), an "ummah;"

- The acceptance of the worship of a multitude of deities besides Allah - a view challenged by strict Tawhid (Islamic monotheism), which dictates that Allah has no partner in worship nor any equal;

- The focus on achieving fame or establishing a legacy, which was replaced by the concept that mankind would be called to account before God on the Qiyamah (day of resurrection);

- The reverence of and compliance with ancestral traditions, a practice challenged by Islam — which instead assigned primacy to submitting to God and following revelation.

These changes lay in the reorientation of society as regards to identity, world view, and the hierarchy of values. From the viewpoint of subsequent generations, this caused a great transformation in the society and moral order of life in the Arabian Peninsula. For Muhammad, although pre-Islamic Arabia exemplified "heedlessness", it was not entirely without merit. Muhammad approved and exhorted certain aspects of the Arab pre-Islamic tradition, such as the care for one's near kin, for widows, orphans, and others in need and for the establishment of justice. However, these values would be re-ordered in importance and placed in the context of strict monotheism.[45]

Although Muhammad's preaching produced a "radical change in moral values based on the sanctions of the new religion, and fear of God and of the Last Judgment", the pre-Islamic tribal practices of the Arabs by no means completely died out.[46]

Economic changes

[edit]Michael Bonner writes on poverty and economics in the Qur'an that the Qur'an provided a blueprint for a new order in society, in which the poor would be treated more fairly than before. This "economy of poverty" prevailed in Islamic theory and practice up until the 13th and 14th centuries. At its heart was a notion of property circulated and purified, in part, through charity, which illustrates a distinctively Islamic way of conceptualizing charity, generosity, and poverty markedly different from "the Christian notion of perennial reciprocity between rich and poor and the ideal of charity as an expression of community love." The Qur'an prohibits riba, often understood as usury or interest, and asks for zakat, alms giving. Some of the recipients of charity appear only once in the Qur'an, and others—such as orphans, parents, and beggars—reappear constantly. Most common is the triad of kinsfolk, poor, and travelers.[47]

Unlike pre-Islamic Arabian society, the Qur'anic idea of economic circulation as a return of goods and obligations was for everyone, whether donors and recipients know each other or not, in which goods move, and society does what it is supposed to do. The Qur'an's distinctive set of economic and social arrangements, in which poverty and the poor have important roles, show signs of newness. The Qur'an told that the guidance comes to a community that regulates its flow of money and goods in the right direction (from top down) and practices generosity as reciprocation for God's bounty. In a broad sense, the narrative underlying the Qur'an is that of a tribal society becoming urbanized. Many scholars, such as Charles C. Torrey and Andrew Rippin, have characterized both the Qur'an and Islam as highly favorable to commerce and to the highly mobile type of society that emerged in the medieval Near East. Muslim tradition (both hadith and historiography) maintains that Muhammad did not permit the construction of any buildings in the market of Medina other than mere tents; nor did he permit any tax or rent to be taken there. This expression of a "free market"—involving the circulation of goods within a single space without payment of fees, taxes, or rent, without the construction of permanent buildings, and without any profiting on the part of the caliphal authority (indeed, of the Caliph himself)—was rooted in the term sadaqa, "voluntary alms". This coherent and highly appealing view of the economic universe had much to do with Islam's early and lasting success. Since the poor were at the heart of this economic universe, the teachings of the Qur'an on poverty had a considerable, even a transforming effect in Arabia, the Near East, and beyond.[47]

Civil changes

[edit]Social welfare in Islam started in the form of the construction and purchase of wells. Upon his hijra to Medina, Muhammad found only one well to be used. The Muslims bought that well, and consequently it was used by the general public. After Muhammad's declaration that "water" was a better form of sadaqah (charity), many of his companions sponsored the digging of new wells. During the Caliphate, the Muslims repaired many of the aging wells in the lands they conquered.[48]

In addition to wells, the Muslims built many tanks and canals. While some canals were excluded for the use of monks (such as a spring purchased by Talhah) and the needy, most canals were open to general public use. Some canals were constructed between settlements, such as the Saad canal that provided water to Anbar, and the Abi Musa Canal to providing water to Basra.[49]

During a famine, Umar (Umar ibn al-Khattab) ordered the construction of a canal in Egypt to connect the Nile with the Red Sea. The purpose of the canal was to facilitate the transport of grain to Arabia through a sea-route, hitherto transported only by land. The canal was constructed within a year by 'Amr ibn al-'As, and Abdus Salam Nadiv writes, Arabia was rid of famine for all the times to come."[50]

Political changes

[edit]Arabia

[edit]Islam began in Arabia in the 7th century under the leadership of Muhammad, who eventually united many of the independent nomadic tribes of Arabia under Islamic rule.[51][52]

Middle East

[edit]The pre-Islamic Middle East was dominated by the Byzantine and Sassanian empires. The Roman–Persian Wars between the two made the empires unpopular amongst the local tribes.

During the early Islamic conquests, the Rashidun army, mostly led by Khalid ibn al-Walid and 'Amr ibn al-'As, defeated both empires, making the Islamic state the dominant power in the region.[53] Within only a decade, Muslims conquered Mesopotamia and Persia during the Muslim conquest of Persia and Roman Syria and Roman Egypt during the early Byzantine–Arab Wars.[54] Esposito argues that the conquest provided greater local autonomy and religious freedom for Jews and some of the Christian Churches in the conquered areas (such as Nestorians, Monophysites, Jacobites and Copts who were deemed heretic by Christian Orthodoxy).[55]

According to Francis Edward Peters:

The conquests destroyed little: what they did suppress were imperial rivalries and sectarian bloodletting among the newly subjected population. The Muslims tolerated Christianity, but they disestablished it; henceforward Christian life and liturgy, its endowments, politics and theology, would be a private and not a public affair. By an exquisite irony, Islam reduced the status of Christians to that which the Christians had earlier thrust upon the Jews, with one difference. The reduction in Christian status was merely judicial; it was unaccompanied by either systematic persecution or a blood lust, and generally, though not elsewhere and at all times, unmarred by vexatious behavior.

Bernard Lewis wrote:

Some even among the Christians of Syria and Egypt preferred the rule of Islam to that of Byzantines... The people of the conquered provinces did not confine themselves to simply accepting the new regime, but in some cases actively assisted in its establishment. In Palestine the Samaritans, according to tradition, gave such effective aid to the Arab invaders that they were for some time exempted from certain taxes, and there are many other reports in the early chronicles of local Jewish and Christian assistance.

However, contemporary records of the conquests paint a more ambiguous picture. The letters of Sophronius of Jerusalem, written in the early days of the conquest, describe churches being "pulled down" and "much destruction and plunder".[56] John of Nikiû, writing in Egypt around the year 690, states that while some Copts welcomed the Arabs due to displeasure with the Byzantine Empire, other Copts, Greek Orthodox Egyptians, and Jews were fearful of them. He states that the taxes of Egyptian Christians and Jews tripled after the conquest, to the point that few could afford it.[57]

Writing around the same time in Mesopotamia, John bar Penkaye describes the Arab conquest as a bloody campaign involving severe destruction and widespread slavery, followed by famine and plague, which he interprets as divine punishment upon his people.[58] His view of Arab rulers is mixed, with positive descriptions of the caliph Muawiyah I and negative descriptions of others, including Muawiyah's son Yazid I. A contemporary Armenian chronicle similarly describes the conquests in terms of looting, burning, enslavement, and destruction. Like John bar Penkaye, he expresses a favorable view of Muawiyah. The author describes rebellions and civil wars breaking out not long after the conquest, demonstrating that "imperial rivalries" were not ended with the arrival of the Arab armies.[59]

Other changes

[edit]Islam reduced the effect of blood feuds and tribal feuds, which was common among the pre-Islamic Arabs, by encouraging compensation in money rather than blood. In case the aggrieved party insisted on blood, unlike the pre-Islamic Arab tradition in which any male relative could be slain, only the culprit himself could be executed.[30][60]

The Cambridge History of Islam states that "Not merely did the Qur'an urge men to show care and concern for the needy, but in its teaching about the Last day it asserted the existence of a sanction applicable to men as individuals in matters where their selfishness was no longer restrained by nomadic ideas of dishonour."[61]

Islam teaches support for the poor and the oppressed.[62] In an effort to protect and help the poor and orphans, regular almsgiving — zakat — was made obligatory for Muslims. This annual alms-giving developed into a form of income tax to be used exclusively for welfare.[63]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c Lewis, Bernard (1998-01-21). "Islamic Revolution". The New York Review of Books.

- ^ Watt (1974), p.234[incomplete short citation]

- ^ Robinson (2004) p.21[incomplete short citation]

- ^ Esposito (1998), p. 98[incomplete short citation]

- ^ "Ak̲h̲lāḳ", Encyclopaedia of Islam Online

- ^ a b c Nancy Gallagher, Encyclopedia of Women & Islamic Cultures, Infanticide and Abandonment of Female Children

- ^ a b c d Leila Ahmed, Women and the Advent of Islam, Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, Vol. 11, No. 4, pp. 665-691

- ^ See:

- Firestone (1999) p. 118;

- "Muhammad", Encyclopaedia of Islam Online[incomplete short citation]

- ^ Watt. Muhammad at Medina and R. B. Serjeant "The Constitution of Medina." Islamic Quarterly 8 (1964) p.4.

- ^ R. B. Serjeant, The Sunnah Jami'ah, pacts with the Yathrib Jews, and the Tahrim of Yathrib: Analysis and translation of the documents comprised in the so-called "Constitution of Medina." Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, Vol. 41, No. 1. 1978), page 4.

- ^ Watt. Muhammad at Medina. pp. 227-228 Watt argues that the initial agreement was shortly after the hijra and the document was amended at a later date specifically after the battle of Badr. Serjeant argues that the constitution is in fact 8 different treaties which can be dated according to events as they transpired in Medina with the first treaty being written shortly after Muhammad's arrival. R. B. Serjeant. "The Sunnah Jâmi'ah, Pacts with the Yathrib Jews, and the Tahrîm of Yathrib: Analysis and Translation of the Documents Comprised in the so called 'Constitution of Medina'." in The Life of Muhammad: The Formation of the Classical Islamic World: Volume iv. Ed. Uri Rubin. Brookfield: Ashgate, 1998, p. 151 and see same article in BSOAS 41 (1978): 18 ff. See also Caetani. Annali dell'Islam, Volume I. Milano: Hoepli, 1905, p. 393. Julius Wellhausen. Skizzen und Vorabeiten, IV, Berlin: Reimer, 1889, p 82f who argue that the document is a single treaty agreed upon shortly after the hijra. Wellhausen argues that it belongs to the first year of Muhammad's residence in Medina, before the battle of Badr in 2/624. Wellhausen bases this judgement on three considerations; first Muhammad is very diffident about his own position, he accepts the pagan tribes within the Ummah, and maintains the Jewish clans as clients of the Ansars see Wellhausen, Excursus, p. 158. Even Moshe Gil a skeptic of Islamic history argues that it was written within 5 months of Muhammad's arrival in Medina. Moshe Gil. "The Constitution of Medina: A Reconsideration." Israel Oriental Studies 4 (1974): p. 45.

- ^ a b c d e f John Esposito, Islam: The Straight Path p. 79

- ^ Esposito, John (2002). Unholy War: Terror in the Name of Islam. Oxford University Press. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-19-515435-1.

- ^ "32. The Book of Marriage from Sahih Muslim translated by Abdul Hamid Siddiqui - Hadith (Hadis) Books".

- ^ Donna Lee Bowen, Encyclopaedia of the Qur'an, Infanticide

- ^ al-Hibri, Azizah (1982). "A study of Islamic herstory: Or how did we ever get into this mess?". Women's Studies International Forum. 5 (2): 207–219. doi:10.1016/0277-5395(82)90028-0.

- ^ Giladi, Avner (May 1990). "Some Observations on Infanticide In Medieval Muslim Society". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 22 (2): 185–200. doi:10.1017/S0020743800033377. S2CID 144324973.

- ^ Kropp, Manfred (July 1997). "Free and bound prepositions: a new look at the inscription Mafray/Qutra 1". Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies. 28: 169–174. JSTOR 41223623.

- ^ "The Merits of the Helpers in Madinah (Ansaar)' of Sahih Bukhari translated by Abdul Hamid Siddiqui - Hadith (Hadis) Books".

- ^ Watt, W. Montgomery. Muhammad: Prophet and Statesman. Oxford University Press, 1961, pp. 229

- ^ a b c Bernard Lewis, Race and Slavery in the Middle East, Oxford Univ Press 1994, chapter 1

- ^ Bernard Lewis, (1992), pp. 78-79

- ^ a b c Encyclopaedia of the Qur'an, Slaves and Slavery

- ^ a b c Turner, Brian S. Islam (ISBN 041512347X). Routledge: 2003, p77-78.

- ^ Unni Wikan, review of Modernizing Women: Gender and Social Change in the Middle East, American Ethnologist, Vol. 22, No. 4 (Nov. 1995), pp. 1078-1079

- ^ Valentine M. Moghadam. Modernizing Women: Gender and Social Change in the Middle East. (Lynne Rienner Publishers, USA, 1993) p. 5

- ^ a b c d Majid Khadduri, Marriage in Islamic Law: The Modernist Viewpoints, American Journal of Comparative Law, Vol. 26, No. 2, pp. 213-218

- ^ Karen Armstrong (2005). "Muhammad". In Lindsay Jones (ed.). Encyclopedia of Religion (2nd ed.). Gale. p. 6224. ISBN 978-0-02-865742-4.

The Quran gave women rights of inheritance and divorce centuries before women in other cultures, including the West, were accorded such legal status.

- ^ a b c The Oxford Dictionary of Islam (2003), p.339

- ^ a b Gerhard Endress, Islam: An Introduction to Islam, Columbia University Press, 1988, p.31

- ^ "Sahih al-Bukhari » Book of Wedlock, Marriage (Nikaah)". Retrieved 2018-08-02.

- ^ "Jami' at-Tirmidhi - The Book on Suckling". Retrieved 2018-08-02.

- ^ Annemarie Schimmel, Islam-: An Introduction, p.65, SUNY Press, 1992

- ^ Interview: William Montgomery Watt Archived August 7, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, by Bashir Maan & Alastair McIntosh (1999). A paper using the material on this interview was published in The Coracle, the Iona Community, summer 2000, issue 3:51, pp. 8-11.

- ^ Bloom and Blair (2002) p.46-47

- ^ Hsu, Shiu-Sian. "Modesty." Encyclopaedia of the Qur'an. Ed. Jane McAuliffe. Vol. 3. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill Academic Publishers, 2003. 403-405. 6 vols.

- ^ Yvonne Yazbeck Haddad, John L. Esposito, Islam, Gender, and Social Change, Oxford University Press US, 2004, p.163

- ^ a b Rhouni, Raja (2009). Secular and Islamic Feminist Critiques in the Work of Fatima Mernissi. Brill. ISBN 978-90-47-42960-9.

- ^ Mernissi, Fatima (1975). Beyond the Veil: Male-female Dynamics in Modern Muslim Society. Saqi Books. p. 66. ISBN 9780863564413.

- ^ "Women in Pre-Islamic Arabia | World Civilization".

- ^ a b c Encyclopaedia of Islam, saghir

- ^ Quran 33:4–5 (Translated by Pickthall)

- ^ "Social Sciences and the Qur'an," in Encyclopaedia of the Qur'an, vol. 5, ed. Jane Dammen McAuliffe. Leiden: Brill, pp. 66-76.

- ^ "Community and Society in the Qur'an," in Encyclopaedia of the Qur'an, vol. 1, ed. Jane Dammen McAuliffe. Leiden: Brill, pp. 385.

- ^ a b Islamic ethics, Encyclopedia of Ethics

- ^ Encyclopaedia of Islam Online, Akhlaq

- ^ a b Michael Bonner, "Poverty and Economics in the Qur'an", Journal of Interdisciplinary History, xxxv:3 (Winter, 2005), 391–406

- ^ Nadvi (2000), pg. 403-4

- ^ Nadvi (2000), pg. 405-6

- ^ Nadvi (2000), pg. 407-8

- ^ Cambridge History of Islam, Vol. 1A (1977), p.57

- ^ Hourani (2003), p.22

- ^ Sonn, pg.24-6

- ^ Esposito, Islam: The Straight Path, extended edition, p.35

- ^ Esposito, Islam: The Straight Path, extended edition, p.36

- ^ Hoyland, Robert (1997). Seeing Islam As Others Saw It: A Survey and Evaluation of Christian, Jewish and Zoroastrian Writings on Early Islam. The Darwin Press, Inc. p. 82. ISBN 978-0878501250.

- ^ "Nikiu Chronicle". Tertullian. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- ^ "John bar Penkaye History, Chapter 15". Tertullian. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- ^ "Sebeos' Chronicle". Attalus. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- ^ Bloom and Blair (2002) p.46

- ^ The Cambridge History of Islam (1970), p. 34

- ^ Nasr (2004), The Heart of Islam: Enduring Values for Humanity, p. 104, ISBN 0-06-073064-1.

- ^ Minou Reeves (2000), Muhammad in Europe, New York University Press, p. 42.

References

[edit]- Forward, Martin (1998). Muhammad: A Short Biography. Oxford: Oneworld. ISBN 978-1-85168-131-0.

- Lewis, Bernard (1984). The Jews of Islam. US: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-05419-3.

- P.J. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel and W.P. Heinrichs (Ed.), Encyclopaedia of Islam Online. Brill Academic Publishers. ISSN 1573-3912.

- Watt, William Montgomery (1974). Muhammad: Prophet and Statesman. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-881078-0.

- Jonathan M. Bloom, Sheila S. Blair (1974). Islam: A Thousand Years of Faith and Power. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-09422-0.

- Manning, Patrick (1990). Slavery and African Life: Occidental, Oriental, and African Slave Trades. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-34867-6.

- Nadvi, Abdus Salam (2000). The ways of the Sahabah. Karachi: Darul Ishaat. Translated by Muhammad Yunus Qureshi.

- Schimmel, Annemarie (1992). Islam: An Introduction. US: SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-1327-2.

- Sonn, Tamara (2004). A Brief History of Islam. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4051-0900-0.