Sherlock Holmes

| Sherlock Holmes | |

|---|---|

| Sherlock Holmes character | |

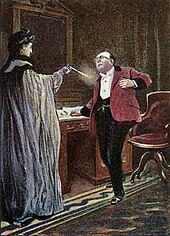

Sherlock Holmes in a 1904 illustration by Sidney Paget | |

| First appearance | A Study in Scarlet (1887) |

| Last appearance | "The Adventure of Shoscombe Old Place" (1927, canon) |

| Created by | Sir Arthur Conan Doyle |

| In-universe information | |

| Occupation | Consulting private detective |

| Family | Mycroft Holmes (brother) |

| Nationality | British |

| Born | 1854 |

Sherlock Holmes (/ˈʃɜːrlɒk ˈhoʊmz/) is a fictional detective created by British author Arthur Conan Doyle. Referring to himself as a "consulting detective" in his stories, Holmes is known for his proficiency with observation, deduction, forensic science and logical reasoning that borders on the fantastic, which he employs when investigating cases for a wide variety of clients, including Scotland Yard.

The character Sherlock Holmes first appeared in print in 1887's A Study in Scarlet. His popularity became widespread with the first series of short stories in The Strand Magazine, beginning with "A Scandal in Bohemia" in 1891; additional tales appeared from then until 1927, eventually totalling four novels and 56 short stories. All but one[a] are set in the Victorian or Edwardian eras between 1880 and 1914. Most are narrated by the character of Holmes's friend and biographer, Dr. John H. Watson, who usually accompanies Holmes during his investigations and often shares quarters with him at the address of 221B Baker Street, London, where many of the stories begin.

Though not the first fictional detective, Sherlock Holmes is arguably the best-known.[1] By the 1990s, over 25,000 stage adaptations, films, television productions, and publications had featured the detective,[2] and Guinness World Records lists him as the most portrayed human literary character in film and television history.[3] Holmes's popularity and fame are such that many have believed him to be not a fictional character but an actual individual;[4][5][6] numerous literary and fan societies have been founded on this pretence. Avid readers of the Holmes stories helped create the modern practice of fandom.[7] The character and stories have had a profound and lasting effect on mystery writing and popular culture as a whole, with the original tales, as well as thousands written by authors other than Conan Doyle, being adapted into stage and radio plays, television, films, video games, and other media for over one hundred years.

Inspiration for the character

Edgar Allan Poe's C. Auguste Dupin is generally acknowledged as the first detective in fiction and served as the prototype for many later characters, including Holmes.[8] Conan Doyle once wrote, "Each [of Poe's detective stories] is a root from which a whole literature has developed ... Where was the detective story until Poe breathed the breath of life into it?"[9] Similarly, the stories of Émile Gaboriau's Monsieur Lecoq were extremely popular at the time Conan Doyle began writing Holmes, and Holmes's speech and behaviour sometimes follow those of Lecoq.[10][11] Doyle has his main characters discuss these literary antecedents near the beginning of A Study in Scarlet, which is set soon after Watson is first introduced to Holmes. Watson attempts to compliment Holmes by comparing him to Dupin, to which Holmes replies that he found Dupin to be "a very inferior fellow" and Lecoq to be "a miserable bungler".[12]

Conan Doyle repeatedly said that Holmes was inspired by the real-life figure of Joseph Bell, a surgeon at the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh, whom Conan Doyle met in 1877 and had worked for as a clerk. Like Holmes, Bell was noted for drawing broad conclusions from minute observations.[13] However, he later wrote to Conan Doyle: "You are yourself Sherlock Holmes and well you know it".[14] Sir Henry Littlejohn, Chair of Medical Jurisprudence at the University of Edinburgh Medical School, is also cited as an inspiration for Holmes. Littlejohn, who was also Police Surgeon and Medical Officer of Health in Edinburgh, provided Conan Doyle with a link between medical investigation and the detection of crime.[15]

Other possible inspirations have been proposed, though never acknowledged by Doyle, such as Maximilien Heller, by French author Henry Cauvain. In this 1871 novel (sixteen years before the first appearance of Sherlock Holmes), Henry Cauvain imagined a depressed, anti-social, opium-smoking polymath detective, operating in Paris.[16][17][18] It is not known if Conan Doyle read the novel, but he was fluent in French.[19]

Biography

Family and early life

Details of Sherlock Holmes' life in Conan Doyle's stories are scarce and often vague. Nevertheless, mentions of his early life and extended family paint a loose biographical picture of the detective.

A statement of Holmes' age in "His Last Bow" places his year of birth at 1854; the story, set in August 1914, describes him as sixty years of age.[20] His parents are not mentioned, although Holmes mentions that his "ancestors" were "country squires". In "The Adventure of the Greek Interpreter", he claims that his grandmother was sister to the French artist Vernet, without clarifying whether this was Claude Joseph, Carle, or Horace Vernet. Holmes' brother Mycroft, seven years his senior, is a government official. Mycroft has a unique civil service position as a kind of human database for all aspects of government policy. Sherlock describes his brother as the more intelligent of the two, but notes that Mycroft lacks any interest in physical investigation, preferring to spend his time at the Diogenes Club.[21][22]

Holmes says that he first developed his methods of deduction as an undergraduate; his earliest cases, which he pursued as an amateur, came from his fellow university students.[23] A meeting with a classmate's father led him to adopt detection as a profession.[24]

Life with Watson

In the first Holmes tale, A Study in Scarlet, financial difficulties lead Holmes and Dr. Watson to share rooms together at 221B Baker Street, London.[25] Their residence is maintained by their landlady, Mrs. Hudson.[26] Holmes works as a detective for twenty-three years, with Watson assisting him for seventeen of those years.[27] Most of the stories are frame narratives written from Watson's point of view, as summaries of the detective's most interesting cases. Holmes frequently calls Watson's records of Holmes's cases sensational and populist, suggesting that they fail to accurately and objectively report the "science" of his craft:

Detection is, or ought to be, an exact science and should be treated in the same cold and unemotional manner. You have attempted to tinge it [A Study in Scarlet] with romanticism, which produces much the same effect as if you worked a love-story or an elopement into the fifth proposition of Euclid. ... Some facts should be suppressed, or, at least, a just sense of proportion should be observed in treating them. The only point in the case which deserved mention was the curious analytical reasoning from effects to causes, by which I succeeded in unravelling it.[28]

Nevertheless, when Holmes recorded a case himself, he was forced to concede that he could more easily understand the need to write it in a manner that would appeal to the public rather than his intention to focus on his own technical skill.[29]

Holmes's friendship with Watson is his most significant relationship. When Watson is injured by a bullet, although the wound turns out to be "quite superficial", Watson is moved by Holmes's reaction:

It was worth a wound; it was worth many wounds; to know the depth of loyalty and love which lay behind that cold mask. The clear, hard eyes were dimmed for a moment, and the firm lips were shaking. For the one and only time I caught a glimpse of a great heart as well as of a great brain. All my years of humble but single-minded service culminated in that moment of revelation.[30]

After confirming Watson's assessment of the wound, Holmes makes it clear to their opponent that the man would not have left the room alive if he genuinely had killed Watson.[30]

Practice

Holmes' clients vary from the most powerful monarchs and governments of Europe, to wealthy aristocrats and industrialists, to impoverished pawnbrokers and governesses. He is known only in select professional circles at the beginning of the first story, but is already collaborating with Scotland Yard. However, his continued work and the publication of Watson's stories raise Holmes's profile, and he rapidly becomes well known as a detective; so many clients ask for his help instead of (or in addition to) that of the police[31] that, Watson writes, by 1887 "Europe was ringing with his name"[32] and by 1895 Holmes has "an immense practice".[33] Police outside London ask Holmes for assistance if he is nearby.[34] A British prime minister[35] and the King of Bohemia[36] visit 221B Baker Street in person to request Holmes's assistance; the President of France awards him the Legion of Honour for capturing an assassin;[37] the King of Scandinavia is a client;[38] and he aids the Vatican at least twice.[39] The detective acts on behalf of the British government in matters of national security several times[40] and declines a knighthood "for services which may perhaps some day be described".[41] However, he does not actively seek fame and is usually content to let the police take public credit for his work.[42]

The Great Hiatus

The first set of Holmes stories was published between 1887 and 1893. Conan Doyle killed off Holmes in a final battle with the criminal mastermind Professor James Moriarty[43] in "The Final Problem" (published 1893, but set in 1891), as Conan Doyle felt that "my literary energies should not be directed too much into one channel".[44] However, the reaction of the public surprised him very much. Distressed readers wrote anguished letters to The Strand Magazine, which suffered a terrible blow when 20,000 people cancelled their subscriptions to the magazine in protest.[45] Conan Doyle himself received many protest letters, and one lady even began her letter with "You brute".[45] Legend has it that Londoners were so distraught upon hearing the news of Holmes's death that they wore black armbands in mourning, though there is no known contemporaneous source for this; the earliest known reference to such events comes from 1949.[46] However, the recorded public reaction to Holmes's death was unlike anything previously seen for fictional events.[7]

After resisting public pressure for eight years, Conan Doyle wrote The Hound of the Baskervilles (serialised in 1901–02, with an implicit setting before Holmes's death). In 1903, Conan Doyle wrote "The Adventure of the Empty House"; set in 1894, Holmes reappears, explaining to a stunned Watson that he had faked his death to fool his enemies.[47] Following "The Adventure of the Empty House", Conan Doyle would sporadically write new Holmes stories until 1927. Holmes aficionados refer to the period from 1891 to 1894—between his disappearance and presumed death in "The Final Problem" and his reappearance in "The Adventure of the Empty House"—as the Great Hiatus.[48] The earliest known use of this expression dates to 1946.[49]

Retirement

In His Last Bow, the reader is told that Holmes has retired to a small farm on the Sussex Downs and taken up beekeeping as his primary occupation.[50] The move is not dated precisely, but can be presumed to be no later than 1904 (since it is referred to retrospectively in "The Adventure of the Second Stain", first published that year).[51] The story features Holmes and Watson coming out of retirement to aid the British war effort. Only one other adventure, "The Adventure of the Lion's Mane", takes place during the detective's retirement.[52]

Personality and habits

Watson describes Holmes as "bohemian" in his habits and lifestyle.[53] Said to have a "cat-like" love of personal cleanliness,[54] at the same time Holmes is an eccentric with no regard for contemporary standards of tidiness or good order. Watson describes him as

in his personal habits one of the most untidy men that ever drove a fellow-lodger to distraction. [He] keeps his cigars in the coal-scuttle, his tobacco in the toe end of a Persian slipper, and his unanswered correspondence transfixed by a jack-knife into the very centre of his wooden mantelpiece. ... He had a horror of destroying documents. ... Thus month after month his papers accumulated, until every corner of the room was stacked with bundles of manuscript which were on no account to be burned, and which could not be put away save by their owner.[55]

While Holmes is characterised as dispassionate and cold, he can be animated and excitable during an investigation. He has a flair for showmanship, often keeping his methods and evidence hidden until the last possible moment so as to impress observers.[56] Holmes is willing to break the law as a means for righting a wrong, contending that "there are certain crimes which the law cannot touch, and which therefore, to some extent, justify private revenge."[57] His companion condones the detective's willingness to do this on behalf of a client—lying to the police, concealing evidence or breaking into houses—when he also feels it morally justifiable.[58]

Except for that of Watson, Holmes avoids casual company. In "The Gloria Scott", he tells the doctor that during two years at college he made only one friend: "I was never a very sociable fellow, Watson ... I never mixed much with the men of my year."[59] The detective goes without food at times of intense intellectual activity, believing that "the faculties become refined when you starve them".[60][61] At times, Holmes relaxes with music, either playing the violin[62] or enjoying the works of composers such as Wagner[63] and Pablo de Sarasate.[64]

Drug use

Holmes occasionally uses addictive drugs, especially in the absence of stimulating cases.[65] He sometimes used morphine and sometimes cocaine, the latter of which he injects in a seven-per cent solution; both drugs were legal in 19th-century England.[66][67][68] As a physician, Watson strongly disapproves of his friend's cocaine habit, describing it as the detective's only vice, and concerned about its effect on Holmes's mental health and intellect.[69][70] In "The Adventure of the Missing Three-Quarter", Watson says that although he has "weaned" Holmes from drugs, the detective remains an addict whose habit is "not dead, but merely sleeping".[71]

Watson and Holmes both use tobacco, smoking cigarettes, cigars, and pipes. Although his chronicler does not consider Holmes's smoking a vice per se, Watson—a physician—does criticise the detective for creating a "poisonous atmosphere" in their confined quarters.[72][73]

Finances

Holmes is known to charge clients for his expenses and claim any reward offered for a problem's solution, such as in "The Adventure of the Speckled Band", "The Red-Headed League", and "The Adventure of the Beryl Coronet". The detective states at one point that "My professional charges are upon a fixed scale. I do not vary them, save when I remit them altogether." In this context, a client is offering to double his fee, and it is implied that wealthy clients habitually pay Holmes more than his standard rate.[74] In "The Adventure of the Priory School", Holmes earns a £6,000 fee[75] (at a time where annual expenses for a rising young professional were in the area of £500).[76] However, Watson notes that Holmes would refuse to help even the wealthy and powerful if their cases did not interest him.[77]

Attitudes towards women

As Conan Doyle wrote to Joseph Bell, "Holmes is as inhuman as a Babbage's Calculating Machine and just about as likely to fall in love."[78] Holmes says of himself that he is "not a whole-souled admirer of womankind",[79] and that he finds "the motives of women ... inscrutable. ... How can you build on such quicksand? Their most trivial actions may mean volumes".[80] In The Sign of Four, he says, "Women are never to be entirely trusted—not the best of them", a feeling Watson notes as an "atrocious sentiment".[81] In "The Adventure of the Lion's Mane", Holmes writes, "Women have seldom been an attraction to me, for my brain has always governed my heart."[82] At the end of The Sign of Four, Holmes states that "love is an emotional thing, and whatever is emotional is opposed to that true, cold reason which I place above all things. I should never marry myself, lest I bias my judgement."[83] Ultimately, Holmes claims outright that "I have never loved."[84]

But while Watson says that the detective has an "aversion to women",[85] he also notes Holmes as having "a peculiarly ingratiating way with [them]".[86] Watson notes that their housekeeper Mrs. Hudson is fond of Holmes because of his "remarkable gentleness and courtesy in his dealings with women. He disliked and distrusted the sex, but he was always a chivalrous opponent."[87] However, in "The Adventure of Charles Augustus Milverton", the detective becomes engaged under false pretenses in order to obtain information about a case, abandoning the woman once he has the information he requires.[88]

Irene Adler

Irene Adler is a retired American opera singer and actress who appears in "A Scandal in Bohemia". Although this is her only appearance, she is one of only a handful of people who bests Holmes in a battle of wits, and the only woman. For this reason, Adler is the frequent subject of pastiche writing.[89] The beginning of the story describes the high regard in which Holmes holds her:

To Sherlock Holmes she is always the woman. I have seldom heard him mention her under any other name. In his eyes she eclipses and predominates the whole of her sex. It was not that he felt any emotion akin to love for Irene Adler. ... And yet there was but one woman to him, and that woman was the late Irene Adler, of dubious and questionable memory.[90]

Five years before the story's events, Adler had a brief liaison with Crown Prince of Bohemia Wilhelm von Ormstein. As the story opens, the Prince is engaged to another. Fearful that the marriage would be called off if his fiancée's family learns of this past impropriety, Ormstein hires Holmes to regain a photograph of Adler and himself. Adler slips away before Holmes can succeed. Her memory is kept alive by the photograph of Adler that Holmes received for his part in the case.[91]

Knowledge and skills

Shortly after meeting Holmes in the first story, A Study in Scarlet (generally assumed to be 1881, though the exact date is not given), Watson assesses the detective's abilities:

- Knowledge of Literature – nil.

- Knowledge of Philosophy – nil.

- Knowledge of Astronomy – nil.

- Knowledge of Politics – Feeble.

- Knowledge of Botany – Variable. Well up in belladonna, opium, and poisons generally. Knows nothing of practical gardening.

- Knowledge of Geology – Practical, but limited. Tells at a glance different soils from each other. After walks, has shown me splashes upon his trousers, and told me by their colour and consistence in what part of London he had received them.

- Knowledge of Chemistry – Profound.

- Knowledge of Anatomy – Accurate, but unsystematic.

- Knowledge of Sensational Literature – Immense. He appears to know every detail of every horror perpetrated in the century.

- Plays the violin well.

- Is an expert singlestick player, boxer, and swordsman.

- Has a good practical knowledge of British law.[92]

In A Study in Scarlet, Holmes claims to be unaware that the Earth revolves around the Sun since such information is irrelevant to his work; after hearing that fact from Watson, he says he will immediately try to forget it. The detective believes that the mind has a finite capacity for information storage, and learning useless things reduces one's ability to learn useful things.[93] The later stories move away from this notion: in The Valley of Fear, he says, "All knowledge comes useful to the detective",[94] and in "The Adventure of the Lion's Mane", the detective calls himself "an omnivorous reader with a strangely retentive memory for trifles".[95] Looking back on the development of the character in 1912, Conan Doyle wrote that "In the first one, the Study in Scarlet, [Holmes] was a mere calculating machine, but I had to make him more of an educated human being as I went on with him."[96]

Despite Holmes's supposed ignorance of politics, in "A Scandal in Bohemia" he immediately recognises the true identity of the disguised "Count von Kramm".[36] At the end of A Study in Scarlet, Holmes demonstrates a knowledge of Latin.[97] The detective cites Hafez,[98] Goethe,[99] as well as a letter from Gustave Flaubert to George Sand in the original French.[100] In The Hound of the Baskervilles, the detective recognises works by Godfrey Kneller and Joshua Reynolds: "Watson won't allow that I know anything of art, but that is mere jealousy since our views upon the subject differ."[101] In "The Adventure of the Bruce-Partington Plans", Watson says that "Holmes lost himself in a monograph which he had undertaken upon the Polyphonic Motets of Lassus", considered "the last word" on the subject—which must have been the result of an intensive and very specialized musicological study which could have had no possible application to the solution of criminal mysteries.[102][103]

Holmes is a cryptanalyst, telling Watson that "I am fairly familiar with all forms of secret writing, and am myself the author of a trifling monograph upon the subject, in which I analyse one hundred and sixty separate ciphers."[104] Holmes also demonstrates a knowledge of psychology in "A Scandal in Bohemia", luring Irene Adler into betraying where she hid a photograph based on the premise that a woman will rush to save her most valued possession from a fire.[105] Another example is in "The Adventure of the Blue Carbuncle", where Holmes obtains information from a salesman with a wager: "When you see a man with whiskers of that cut and the 'Pink 'un' protruding out of his pocket, you can always draw him by a bet ... I daresay that if I had put 100 pounds down in front of him, that man would not have given me such complete information as was drawn from him by the idea that he was doing me on a wager."[106]

Maria Konnikova points out in an interview with D. J. Grothe that Holmes practises what is now called mindfulness, concentrating on one thing at a time, and almost never "multitasks". She adds that in this he predates the science showing how helpful this is to the brain.[107]

Holmesian deduction

Holmes observes the dress and attitude of his clients and suspects, noting skin marks (such as tattoos), contamination (such as ink stains or clay on boots), emotional state, and physical condition in order to deduce their origins and recent history. The style and state of wear of a person's clothes and personal items are also commonly relied on; in the stories, Holmes is seen applying his method to items such as walking sticks,[108] pipes,[109] and hats.[110] For example, in "A Scandal in Bohemia", Holmes infers that Watson had got wet lately and had "a most clumsy and careless servant girl". When Watson asks how Holmes knows this, the detective answers:

It is simplicity itself ... my eyes tell me that on the inside of your left shoe, just where the firelight strikes it, the leather is scored by six almost parallel cuts. Obviously they have been caused by someone who has very carelessly scraped round the edges of the sole in order to remove crusted mud from it. Hence, you see, my double deduction that you had been out in vile weather, and that you had a particularly malignant boot-slitting specimen of the London slavey.[111]

In the first Holmes story, A Study in Scarlet, Dr. Watson compares Holmes to C. Auguste Dupin, Edgar Allan Poe's fictional detective, who employed a similar methodology. Alluding to an episode in "The Murders in the Rue Morgue", where Dupin determines what his friend is thinking despite their having walked together in silence for a quarter of an hour, Holmes remarks: "That trick of his breaking in on his friend's thoughts with an apropos remark ... is really very showy and superficial."[112] Nevertheless, Holmes later performs the same 'trick' on Watson in "The Cardboard Box"[113] and "The Adventure of the Dancing Men".[114]

Though the stories always refer to Holmes's intellectual detection method as "deduction", Holmes primarily relies on abduction: inferring an explanation for observed details.[115][116][117] "From a drop of water," he writes, "a logician could infer the possibility of an Atlantic or a Niagara without having seen or heard of one or the other."[118] However, Holmes does employ deductive reasoning as well. The detective's guiding principle, as he says in The Sign of Four, is: "When you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth."[119]

Despite Holmes's remarkable reasoning abilities, Conan Doyle still paints him as fallible in this regard (this being a central theme of "The Yellow Face").[120]

Forensic science

Though Holmes is famed for his reasoning capabilities, his investigative technique relies heavily on the acquisition of hard evidence. Many of the techniques he employs in the stories were at the time in their infancy.[121][122]

The detective is particularly skilled in the analysis of trace evidence and other physical evidence, including latent prints (such as footprints, hoof prints, and shoe and tire impressions) to identify actions at a crime scene,[123] using tobacco ashes and cigarette butts to identify criminals,[124] utilizing handwriting analysis and graphology,[125] comparing typewritten letters to expose a fraud,[126] using gunpowder residue to expose two murderers,[127] and analyzing small pieces of human remains to expose two murders.[128]

Because of the small scale of much of his evidence, the detective often uses a magnifying glass at the scene and an optical microscope at his Baker Street lodgings. He uses analytical chemistry for blood residue analysis and toxicology to detect poisons; Holmes's home chemistry laboratory is mentioned in "The Naval Treaty".[129] Ballistics feature in "The Adventure of the Empty House" when spent bullets are recovered to be matched with a suspected murder weapon, a practice which became regular police procedure only some fifteen years after the story was published.[130]

Laura J. Snyder has examined Holmes's methods in the context of mid- to late-19th-century criminology, demonstrating that, while sometimes in advance of what official investigative departments were formally using at the time, they were based upon existing methods and techniques. For example, fingerprints were proposed to be distinct in Conan Doyle's day, and while Holmes used a thumbprint to solve a crime in "The Adventure of the Norwood Builder" (generally held to be set in 1895), the story was published in 1903, two years after Scotland Yard's fingerprint bureau opened.[122][131] Though the effect of the Holmes stories on the development of forensic science has thus often been overstated, Holmes inspired future generations of forensic scientists to think scientifically and analytically.[132]

Disguises

Holmes displays a strong aptitude for acting and disguise. In several stories ("The Sign of Four", "The Adventure of Charles Augustus Milverton", "The Man with the Twisted Lip", "The Adventure of the Empty House" and "A Scandal in Bohemia"), to gather evidence undercover, he uses disguises so convincing that Watson fails to recognise him. In others ("The Adventure of the Dying Detective" and "A Scandal in Bohemia"), Holmes feigns injury or illness to incriminate the guilty. In the latter story, Watson says, "The stage lost a fine actor ... when [Holmes] became a specialist in crime."[133]

Guy Mankowski has said of Holmes that his ability to change his appearance to blend into any situation "helped him personify the idea of the English eccentric chameleon, in a way that prefigured the likes of David Bowie".[134]

Agents

Until Watson's arrival at Baker Street, Holmes largely worked alone, only occasionally employing agents from the city's underclass. These agents included a variety of informants, such as Langdale Pike, a "human book of reference upon all matters of social scandal",[135] and Shinwell Johnson, who acted as Holmes's "agent in the huge criminal underworld of London".[136] The best known of Holmes's agents are a group of street children he called "the Baker Street Irregulars".[137][138]

Combat

Pistols

Holmes and Watson often carry pistols with them to confront criminals—in Watson's case, his old service weapon (probably a Mark III Adams revolver, issued to British troops during the 1870s).[139] Holmes and Watson shoot the eponymous hound in The Hound of the Baskervilles,[140] and in "The Adventure of the Empty House", Watson pistol-whips Colonel Sebastian Moran.[141] In "The Problem of Thor Bridge", Holmes uses Watson's revolver to solve the case through an experiment.

Other weapons

As a gentleman, Holmes often carries a stick or cane. He is described by Watson as an expert at singlestick,[92] and uses his cane twice as a weapon.[142] In A Study in Scarlet, Watson describes Holmes as an expert swordsman,[92] and in "The Gloria Scott", the detective says he practised fencing while at university.[59] In several stories ("A Case of Identity", "The Red-Headed League", "The Adventure of the Six Napoleons"), Holmes wields a riding crop, described in the latter story as his "favourite weapon".[143]

Personal combat

The detective is described (or demonstrated) as possessing above-average physical strength. In "The Yellow Face", Holmes's chronicler says, "Few men were capable of greater muscular effort."[144] In "The Adventure of the Speckled Band", Dr. Roylott demonstrates his strength by bending a fire poker in half. Watson describes Holmes as laughing and saying, "'If he had remained I might have shown him that my grip was not much more feeble than his own.' As he spoke he picked up the steel poker and, with a sudden effort, straightened it out again."[145]

Holmes is an adept bare-knuckle fighter; "The Gloria Scott" mentions that Holmes boxed while at university.[59] In The Sign of Four, he introduces himself to McMurdo, a prize fighter, as "the amateur who fought three rounds with you at Alison's rooms on the night of your benefit four years back". McMurdo remembers: "Ah, you're one that has wasted your gifts, you have! You might have aimed high if you had joined the fancy."[146] In "The Yellow Face", Watson says: "He was undoubtedly one of the finest boxers of his weight that I have ever seen."[147] In "The Solitary Cyclist", Holmes visits a country pub to make enquiries regarding a certain Mr Woodley which results in violence. Mr Woodley, Holmes tells Watson,[148]

... had been drinking his beer in the tap-room, and had heard the whole conversation. Who was I? What did I want? What did I mean by asking questions? He had a fine flow of language, and his adjectives were very vigorous. He ended a string of abuse by a vicious backhander, which I failed to entirely avoid. The next few minutes were delicious. It was a straight left against a slogging ruffian. I emerged as you see me. Mr. Woodley went home in a cart.[148]

Another character subsequently refers to Mr Woodley as looking "much disfigured" as a result of his encounter with Holmes.[149]

In "The Adventure of the Empty House", Holmes tells Watson that he used a Japanese martial art known as baritsu to fling Moriarty to his death in the Reichenbach Falls.[150] "Baritsu" is Conan Doyle's version of bartitsu, which combines jujitsu with boxing and cane fencing.[151]

Reception

Popularity

The first two Sherlock Holmes stories, the novels A Study in Scarlet (1887) and The Sign of the Four (1890), were moderately well received, but Holmes first became very popular early in 1891 when the first six short stories featuring the character were published in The Strand Magazine. Holmes became widely known in Britain and America.[1] The character was so well known that in 1893 when Arthur Conan Doyle killed Holmes in the short story "The Final Problem", the strongly negative response from readers was unlike any previous public reaction to a fictional event. The Strand reportedly lost more than 20,000 subscribers as a result of Holmes's death.[152] Public pressure eventually contributed to Conan Doyle writing another Holmes story in 1901 and resurrecting the character in a story published in 1903.[7] In Japan, Sherlock Holmes (and Alice from Alice's Adventures in Wonderland) became immensely popular in the country in the 1890s as it was opening up to the West, and they are cited as two British fictional Victorians who left an enormous creative and cultural legacy there.[153]

Many fans of Sherlock Holmes have written letters to Holmes's address, 221B Baker Street. Though the address 221B Baker Street did not exist when the stories were first published, letters began arriving to the large Abbey National building which first encompassed that address almost as soon as it was built in 1932. Fans continue to send letters to Sherlock Holmes;[154] these letters are now delivered to the Sherlock Holmes Museum.[155] Some of the people who have sent letters to 221B Baker Street believe Holmes is real.[4] Members of the general public have also believed Holmes actually existed. In a 2008 survey of British teenagers, 58 per cent of respondents believed that Sherlock Holmes was a real individual.[5]

Some scholarly discussion of Holmes has occasionally been written (usually facetiously) from the perspective of Holmes and Dr. Watson having existed; an example of this are the five critical essays, "Studies in Sherlock Holmes", by the author and essayist Dorothy L. Sayers in her 1946 non-fiction collection, Unpopular Opinions, including an article examining Watson's signature which was allegedly visible in some original Strand illustrations.[156]

The Sherlock Holmes stories continue to be widely read.[1] Holmes's continuing popularity has led to many reimaginings of the character in adaptations.[7] Guinness World Records, which awarded Sherlock Holmes the title for "most portrayed literary human character in film & TV" in 2012, released a statement saying that the title "reflects his enduring appeal and demonstrates that his detective talents are as compelling today as they were 125 years ago".[3]

Honours

The London Metropolitan Railway named one of its twenty electric locomotives deployed in the 1920s for Sherlock Holmes. He was the only fictional character so honoured, along with eminent Britons such as Lord Byron, Benjamin Disraeli, and Florence Nightingale.[157]

A number of London streets are associated with Holmes. York Mews South, off Crawford Street, was renamed Sherlock Mews, and Watson's Mews is near Crawford Place.[158] The Sherlock Holmes is a public house in Northumberland Street in London which contains a large collection of memorabilia related to Holmes, the original collection having been put together for display in Baker Street during the Festival of Britain in 1951.[159][160]

In 2002, the Royal Society of Chemistry bestowed an honorary fellowship on Holmes for his use of forensic science and analytical chemistry in popular literature, making him (as of 2024) the only fictional character thus honoured.[161] Holmes has been commemorated numerous times on UK postage stamps issued by the Royal Mail, most recently in their August 2020 series to celebrate the Sherlock television series.[162]

There are multiple statues of Sherlock Holmes around the world. The first, sculpted by John Doubleday, was unveiled in Meiringen, Switzerland, in September 1988. The second was unveiled in October 1988 in Karuizawa, Japan, and was sculpted by Yoshinori Satoh. The third was installed in Edinburgh, Scotland, in 1989, and was sculpted by Gerald Laing.[163] In 1999, a statue of Sherlock Holmes in London, also by John Doubleday, was unveiled near the fictional detective's address, 221B Baker Street.[164] In 2001, a sculpture of Holmes and Arthur Conan Doyle by Irena Sedlecká was unveiled in a statue collection in Warwickshire, England.[165] A sculpture depicting both Holmes and Watson was unveiled in 2007 in Moscow, Russia, based partially on Sidney Paget's illustrations and partially on the actors in The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson.[166] In 2015, a sculpture of Holmes by Jane DeDecker was installed in the police headquarters of Edmond, Oklahoma, United States.[167] In 2019, a statue of Holmes was unveiled in Chester, Illinois, United States, as part of a series of statues honouring cartoonist E. C. Segar and his characters. The statue is titled "Sherlock & Segar", and the face of the statue was modelled on Segar.[168]

Societies

In 1934, the Sherlock Holmes Society (in London) and the Baker Street Irregulars (in New York) were founded. The latter is still active. The Sherlock Holmes Society was dissolved later in the 1930s, but was succeeded by a society with a slightly different name, the Sherlock Holmes Society of London, which was founded in 1951 and remains active.[169][170] These societies were followed by many more, first in the US (where they are known as "scion societies"—offshoots—of the Baker Street Irregulars) and then in England and Denmark. There are at least 250 societies worldwide, including Australia, Canada (such as The Bootmakers of Toronto), India, and Japan.[171] Fans tend to be called "Holmesians" in the UK and "Sherlockians" in the US,[172][173][174] though recently "Sherlockian" has also come to refer to fans of the Benedict Cumberbatch-led BBC series regardless of location.[175]

Legacy

The detective story

Although Holmes is not the original fictional detective, his name has become synonymous with the role. Doyle's Sherlock Holmes stories introduced multiple literary devices that have become major conventions in detective fiction, such as the companion character who is not as clever as the detective and has solutions explained to him (thus informing the reader as well), as with Dr. Watson in the Holmes stories. Other conventions introduced by Doyle include the arch-criminal who is too clever for the official police to defeat, like Holmes's adversary Professor Moriarty, and the use of forensic science to solve cases.[1]

The Sherlock Holmes stories established crime fiction as a respectable genre popular with readers of all backgrounds, and Doyle's success inspired many contemporary detective stories.[176] Holmes influenced the creation of other "eccentric gentleman detective" characters, like Agatha Christie's fictional detective Hercule Poirot, introduced in 1920.[177] Holmes also inspired a number of anti-hero characters "almost as an antidote to the masterful detective", such as the gentleman thief characters A. J. Raffles (created by E. W. Hornung in 1898) and Arsène Lupin (created by Maurice Leblanc in 1905).[176]

"Elementary, my dear Watson"

The phrase "Elementary, my dear Watson" has become one of the most quoted and iconic aspects of the character. However, although Holmes often observes that his conclusions are "elementary", and occasionally calls Watson "my dear Watson", the phrase "Elementary, my dear Watson" is never uttered in any of the sixty stories by Conan Doyle.[178] One of the nearest approximations of the phrase appears in "The Adventure of the Crooked Man" (1893) when Holmes explains a deduction: "'Excellent!' I cried. 'Elementary,' said he."[179][180]

William Gillette is widely considered to have originated the phrase with the formulation, "Oh, this is elementary, my dear fellow", allegedly in his 1899 play Sherlock Holmes. However, the script was revised numerous times over the course of some three decades of revivals and publications, and the phrase is present in some versions of the script, but not others.[178] The appearance of the line "Elementary, my dear Potson" in a Sherlock Holmes parody from 1901 has led some authors to speculate that, rather than this being an incidental formulation, the parodist drew upon an already well-established occurrences of "Elementary, my dear Watson."[181][182]

The exact phrase, as well as close variants, can be seen in newspaper and journal articles as early as 1909.[178][183] It was also used by P. G. Wodehouse in his novel Psmith, Journalist, which was first serialised in The Captain magazine between October 1909 and February 1910; the phrase occurred in the January 1910 instalment. The phrase became familiar with the American public in part due to its use in the Rathbone-Bruce series of films from 1939 to 1946.[184]

The Great Game

Conan Doyle's 56 short stories and four novels are known as the "canon" by Holmes aficionados. The Great Game (also known as the Holmesian Game, the Sherlockian Game, or simply the Game, also the Higher Criticism) applies the methods of literary and especially Biblical criticism to the canon, operating on the pretense that Holmes and Watson were real people and that Conan Doyle was not the author of the stories but Watson's literary agent. From this basis, it attempts to resolve or explain away contradictions in the canon—such as the location of Watson's war wound, described as being in his shoulder in A Study in Scarlet and in his leg in The Sign of Four—and clarify details about Holmes, Watson and their world, such as the exact dates of events in the stories, combining historical research with references from the stories to construct scholarly analyses.[185][186][187]

For example, one detail analyzed in the Game is Holmes's birth date. The chronology of the stories is notoriously difficult, with many stories lacking dates and many others containing contradictory ones. Christopher Morley and William Baring-Gould contend that the detective was born on 6 January 1854, the year being derived from the statement in "His Last Bow" that he was 60 years of age in 1914, while the precise day is derived from broader, non-canonical speculation.[188] This is the date the Baker Street Irregulars work from, with their annual dinner being held each January.[189][190] Laurie R. King instead argues that details in "The Gloria Scott" (a story with no precise internal date) indicate that Holmes finished his second (and final) year of university in 1880 or 1885. If he began university at age 17, his birth year could be as late as 1868.[191]

Museums and special collections

For the 1951 Festival of Britain, Holmes's living room was reconstructed as part of a Sherlock Holmes exhibition, with a collection of original material. After the festival, items were transferred to The Sherlock Holmes (a London pub) and the Conan Doyle collection housed in Lucens, Switzerland, by the author's son, Adrian. Both exhibitions, each with a Baker Street sitting-room reconstruction, are open to the public.[192]

In 1969, the Toronto Reference Library began a collection of materials related to Conan Doyle. Stored today in Room 221B, this vast collection is accessible to the public.[193] Similarly, in 1974 the University of Minnesota founded a collection that is now "the world's largest gathering of material related to Sherlock Holmes and his creator". Access is closed to the general public, but is occasionally open to tours.[194][195]

In 1990, the Sherlock Holmes Museum opened on Baker Street in London, followed the next year by a museum in Meiringen (near the Reichenbach Falls) dedicated to the detective.[192] A private Conan Doyle collection is a permanent exhibit at the Portsmouth City Museum, where the author lived and worked as a physician.[196]

Postcolonial criticism

The Sherlock Holmes stories have been scrutinized by a few academics for themes of empire and colonialism.

Susan Cannon Harris claims that themes of contagion and containment are common in the Holmes series, including the metaphors of Eastern foreigners as the root cause of "infection" within and around Europe.[197] Lauren Raheja, writing in the Marxist journal Nature, Society, and Thought, claims that Doyle used these characteristics to paint eastern colonies in a negative light, through their continually being the source of threats. For example, in one story, Doyle makes mention of the Sumatran cannibals (also known as Batak) who throw poisonous darts, and in "The Speckled Band", a "long residence in the tropics" was a negative influence on one antagonist's bad temper.[198] Yumna Siddiqi argues that Doyle depicted returned colonials as "marginal, physically ravaged characters that threaten the peace", while putting non-colonials in a much more positive light.[199]

Adaptations and derived works

The popularity of Sherlock Holmes has meant that many writers other than Arthur Conan Doyle have created tales of the detective in a wide variety of different media, with varying degrees of fidelity to the original characters, stories, and setting. The first known period pastiche dates from 1891. Titled "The Late Sherlock Holmes", it was written by Conan Doyle's close friend J. M. Barrie.[200]

Adaptations have seen the character taken in radically different directions or placed in different times or even universes. For example, Holmes falls in love and marries in Laurie R. King's Mary Russell series, is re-animated after his death to fight future crime in the animated series Sherlock Holmes in the 22nd Century, and is meshed with the setting of H. P. Lovecraft's Cthulhu Mythos in Neil Gaiman's "A Study in Emerald" (which won the 2004 Hugo Award for Best Short Story). An especially influential pastiche was Nicholas Meyer's The Seven-Per-Cent Solution, a 1974 New York Times bestselling novel (made into the 1976 film of the same name) in which Holmes's cocaine addiction has progressed to the point of endangering his career. It served to popularize the trend of incorporating clearly identified and contemporaneous historical figures (such as Oscar Wilde, Aleister Crowley, Sigmund Freud, or Jack the Ripper) into Holmesian pastiches, something Conan Doyle himself never did.[201][202][203] Another common pastiche approach is to create a new story fully detailing an otherwise-passing canonical reference (such as an aside by Conan Doyle mentioning the "giant rat of Sumatra, a story for which the world is not yet prepared" in "The Adventure of the Sussex Vampire").[204]

The first translation of a Sherlock Holmes story into a Chinese variety was done by Chinese Progress in 1896. That publication rendered the name as 呵爾唔斯, which would be 呵尔唔斯 in Simplified Chinese and Hē'ěrwúsī in Modern Standard Mandarin. Shanghai Civilization Books later issued versions rendering Holmes's name differently, as 福爾摩斯 in Traditional Chinese, which would be 福尔摩斯 in Simplified Chinese and Fú'ěrmósī in Modern Standard Mandarin; this version became the common way of rendering "Holmes" in Chinese languages.[205]

Related and derivative writings

In addition to the Holmes canon, Conan Doyle's 1898 "The Lost Special" features an unnamed "amateur reasoner" intended to be identified as Holmes by his readers. The author's explanation of a baffling disappearance argued in Holmesian style poked fun at his own creation. Similar Conan Doyle short stories are "The Field Bazaar", "The Man with the Watches", and 1924's "How Watson Learned the Trick", a parody of the Watson–Holmes breakfast-table scenes. The author wrote other material featuring Holmes, especially plays: 1899's Sherlock Holmes (with William Gillette), 1910's The Speckled Band, and 1921's The Crown Diamond (the basis for "The Adventure of the Mazarin Stone").[206] These non-canonical works have been collected in several works released since Conan Doyle's death.[207]

In terms of writers other than Conan Doyle, authors as diverse as Agatha Christie, Anthony Burgess, Neil Gaiman, Dorothy B. Hughes, Stephen King, Tanith Lee, A. A. Milne, and P. G. Wodehouse have all written Sherlock Holmes pastiches. Contemporary with Conan Doyle, Maurice Leblanc directly featured Holmes in his popular series about the gentleman thief, Arsène Lupin, though legal objections from Conan Doyle forced Leblanc to modify the name to "Herlock Sholmes" in reprints and later stories.[208] In 1944, American mystery writers Frederic Dannay and Manfred B. Lee (writing under their joint pseudonym Ellery Queen) published The Misadventures of Sherlock Holmes, a collection of thirty-three pastiches written by various well-known authors.[209][210] Mystery writer John Dickson Carr collaborated with Arthur Conan Doyle's son, Adrian Conan Doyle, on The Exploits of Sherlock Holmes, a pastiche collection from 1954.[211] In 2011, Anthony Horowitz published a Sherlock Holmes novel, The House of Silk, presented as a continuation of Conan Doyle's work and with the approval of the Conan Doyle estate;[212] a follow-up, Moriarty, appeared in 2014.[213] The "MX Book of New Sherlock Holmes Stories" series of pastiches, edited by David Marcum and published by MX Publishing, has reached over forty volumes and features hundreds of stories echoing the original canon which were compiled for the restoration of Undershaw and the support of Stepping Stones School, now housed in it.[214][215]

Some authors have written tales centred on characters from the canon other than Holmes. Anthologies edited by Michael Kurland and George Mann are entirely devoted to stories told from the perspective of characters other than Holmes and Watson. John Gardner, Michael Kurland, and Kim Newman, amongst many others, have all written tales in which Holmes's nemesis Professor Moriarty is the main character. Mycroft Holmes has been the subject of several efforts: Enter the Lion by Michael P. Hodel and Sean M. Wright (1979),[216] a four-book series by Quinn Fawcett,[217] and 2015's Mycroft Holmes, by Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and Anna Waterhouse.[218] M. J. Trow has written a series of seventeen books using Inspector Lestrade as the central character, beginning with The Adventures of Inspector Lestrade in 1985.[219] Carole Nelson Douglas' Irene Adler series is based on "the woman" from "A Scandal in Bohemia", with the first book (1990's Good Night, Mr. Holmes) retelling that story from Adler's point of view.[220] Martin Davies has written three novels where Baker Street housekeeper Mrs. Hudson is the protagonist.[221]

In 1980's The Name of the Rose, Italian author Umberto Eco creates a Sherlock Holmes of the 1320s in the form of a Franciscan friar and main protagonist named Brother William of Baskerville, his name a clear reference to Holmes per The Hound of the Baskervilles.[222] Brother William investigates a series of murders in the abbey alongside his novice Adso of Melk, who acts as his Dr. Watson. Furthermore, Umberto Eco's description of Brother William bears marked similarities in both physique and personality to Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's description of Sherlock Holmes in A Study in Scarlet.[223]

Laurie R. King recreated Holmes in her Mary Russell series (beginning with 1994's The Beekeeper's Apprentice), set during the First World War and the 1920s. Her Holmes, semi-retired in Sussex, meets a teenage American girl. Recognising a kindred spirit, he trains her as his apprentice and subsequently marries her. As of 2024, the series includes eighteen base novels and additional writings.[224]

The Final Solution, a 2004 novella by Michael Chabon, concerns an unnamed but long-retired detective interested in beekeeping who tackles the case of a missing parrot belonging to a Jewish refugee boy.[225] Mitch Cullin's novel A Slight Trick of the Mind (2005) takes place two years after the end of the Second World War and explores an old and frail Sherlock Holmes (now 93) as he comes to terms with a life spent in emotionless logic;[226] this was also adapted into a film, 2015's Mr. Holmes.[227]

There have been many scholarly works dealing with Sherlock Holmes, some working within the bounds of the Great Game, and some written from the perspective that Holmes is a fictional character. In particular, there have been three major annotated editions of the complete series. The first was William Baring-Gould's 1967 The Annotated Sherlock Holmes. This two-volume set was ordered to fit Baring-Gould's preferred chronology, and was written from a Great Game perspective. The second was 1993's The Oxford Sherlock Holmes (general editor: Owen Dudley Edwards), a nine-volume set written in a straight scholarly manner. The most recent is Leslie Klinger's The New Annotated Sherlock Holmes (2004–05), a three-volume set that returns to a Great Game perspective.[228][229]

Adaptations in other media

In 2012, Guinness World Records listed Holmes as the most portrayed literary human character in film and television history, with more than 75 actors playing the part in over 250 productions.[3]

The 1899 play Sherlock Holmes, by Conan Doyle and William Gillette, was a synthesis of several Conan Doyle stories. In addition to its popularity, the play is significant because it, rather than the original stories, introduced one of the key visual qualities commonly associated with Holmes today: his calabash pipe;[230] the play also formed the basis for Gillette's 1916 film, Sherlock Holmes. Gillette performed as Holmes some 1,300 times. In the early 1900s, H. A. Saintsbury took over the role from Gillette for a tour of the play. Between this play and Conan Doyle's own stage adaptation of "The Adventure of the Speckled Band", Saintsbury portrayed Holmes over 1,000 times.[231]

Holmes's first screen appearance was in the 1900 Mutoscope film, Sherlock Holmes Baffled.[232] From 1921 to 1923, Eille Norwood played Holmes in forty-seven silent films (45 shorts and two features), in a series of performances that Conan Doyle spoke highly of.[2][233] 1929's The Return of Sherlock Holmes was the first sound title to feature Holmes.[234] From 1939 to 1946, Basil Rathbone played Holmes and Nigel Bruce played Watson in fourteen US films (two for 20th Century Fox and a dozen for Universal Pictures) and in The New Adventures of Sherlock Holmes radio show. While the Fox films were period pieces, the Universal films abandoned Victorian Britain and moved to a then-contemporary setting in which Holmes occasionally battled Nazis.[235]

The character has also enjoyed numerous radio adaptations, beginning with Edith Meiser's The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes,[236] which ran from 1930 to 1936. Basil Rathbone and Nigel Bruce continued with their roles for most of the run of The New Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, airing from 1939 to 1950. Bert Coules, having dramatised the entire Holmes canon for BBC Radio Four from 1989 to 1998,[237][238] penned The Further Adventures of Sherlock Holmes between 2002 and 2010. This pastiche series also aired on Radio Four and starred Clive Merrison as Holmes and Michael Williams and then Andrew Sachs as Watson.[237][239]

The 1984–85 Italian/Japanese anime series Sherlock Hound adapted the Holmes stories for children, with its characters being anthropomorphic dogs. The series was co-directed by Hayao Miyazaki.[240] Between 1979 and 1986, the Soviet studio Lenfilm produced a series of five television films, The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson. The series were split into eleven episodes and starred Vasily Livanov as Holmes and Vitaly Solomin as Watson. For his performance, in 2006 Livanov was appointed an Honorary Member of the Order of the British Empire.[241][242]

Jeremy Brett played the detective in Sherlock Holmes for Granada Television from 1984 to 1994. Watson was played by David Burke (in the first two series) and Edward Hardwicke (in the remainder).[243] Brett and Hardwicke also appeared on stage in 1988–89 in The Secret of Sherlock Holmes, directed by Patrick Garland.[244]

In the 2004–2012 Fox's show House, the titular character Gregory House is an adaptation of Sherlock Holmes in a medical drama setting. The two characters share many parallels and House's name is a play on Holmes' one.[245][246]

The 2009 film Sherlock Holmes earned Robert Downey Jr. a Golden Globe Award for his portrayal of Holmes and co-starred Jude Law as Watson.[247] Downey and Law returned for a 2011 sequel, Sherlock Holmes: A Game of Shadows.

Benedict Cumberbatch plays a modern version of the detective and Martin Freeman as a modern version of John Watson in the BBC One TV series Sherlock, which premiered in 2010. In the series, created by Mark Gatiss and Steven Moffat, the stories' original Victorian setting is replaced by present-day London, with Watson a veteran of the modern War in Afghanistan.[248] Similarly, Elementary premiered on CBS in 2012 and ran for seven seasons until 2019. Set in contemporary New York City, the series stars Jonny Lee Miller as Sherlock Holmes and Lucy Liu as a female Dr. Joan Watson.[249] The series was filmed primarily in New York City, and, by the end of season two, Miller became the actor who had portrayed Sherlock Holmes the most in television and/or film.[250]

The 2015 film Mr. Holmes starred Ian McKellen as a retired Sherlock Holmes living in Sussex, in 1947, who grapples with an unsolved case involving a beautiful woman. The film is based on Mitch Cullin's 2005 novel A Slight Trick of the Mind.[251][252]

The 2018 television adaptation, Miss Sherlock, was a Japanese-language production and the first adaptation with a woman (portrayed by Yūko Takeuchi) in the signature role. The episodes were based in modern-day Tokyo, with many references to Conan Doyle's stories.[253][254]

Holmes has also appeared in video games, including the Sherlock Holmes series of eight main titles. According to the publisher, Frogwares, by 2017 the series sold over seven million copies.[255]

Copyright issues

The copyright for Conan Doyle's works expired in the United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia at the end of 1980, fifty years after Conan Doyle's death.[256][257] In the United Kingdom, it was revived in 1996 due to new provisions harmonising UK law with that of the European Union, and expired again at the end of 2000 (seventy years after Conan Doyle's death).[258] The author's works are now in the public domain in those countries.[259][260]

In the United States, all works published before 1923 entered public domain by 1998, but, as ten Holmes stories were published after that date, the Conan Doyle estate maintained that the Holmes and Watson characters as a whole were still under copyright.[257][261] In 2013, Leslie S. Klinger (lawyer and editor of The New Annotated Sherlock Holmes) sued the Conan Doyle estate in order to have the characters of Holmes and Watson declared public domain in the United States. Klinger was successful: as a result, the only stories still under copyright in the US due to the ruling, as of that time, were those collected in The Case-Book of Sherlock Holmes other than "The Adventure of the Mazarin Stone" and "The Problem of Thor Bridge": a total of ten stories.[260][262][263]

In 2020, although the United States court ruling and the passage of time meant that most of the Holmes stories and characters were in the public domain in that country, the Doyle estate legally challenged the use of Sherlock Holmes in the film Enola Holmes in a complaint filed in the United States.[264] The Doyle estate alleged that the film depicts Holmes with personality traits that were only exhibited by the character in the stories still under copyright.[265][266] On 18 December 2020, the lawsuit was dismissed with prejudice by stipulation of all parties.[267][268]

The remaining ten Holmes stories moved out of copyright in the United States between 1 January 2019 and 1 January 2023, leaving the stories and characters completely in the public domain in the US as of the latter date.[269][270][271]

Works

Novels

- A Study in Scarlet (published November 1887 in Beeton's Christmas Annual)

- The Sign of the Four (published February 1890 in Lippincott's Monthly Magazine)

- The Hound of the Baskervilles (serialised 1901–1902 in The Strand)

- The Valley of Fear (serialised 1914–1915 in The Strand)

Short story collections

The short stories, originally published in magazines, were later collected in five anthologies:

- The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes (stories published 1891–1892 in The Strand)

- The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes (stories published 1892–1893 in The Strand)

- The Return of Sherlock Holmes (stories published 1903–1904 in The Strand)

- His Last Bow: Some Later Reminiscences of Sherlock Holmes (stories published 1908–1917)

- The Case-Book of Sherlock Holmes (stories published 1921–1927)

See also

Notes

Sherlock Holmes story references

- Klinger, Leslie (ed.). The New Annotated Sherlock Holmes, Volume I (New York: W. W. Norton, 2005). ISBN 0-393-05916-2 ("Klinger I")

- Klinger, Leslie (ed.). The New Annotated Sherlock Holmes, Volume II (New York: W. W. Norton, 2005). ISBN 0-393-05916-2 ("Klinger II")

- Klinger, Leslie (ed.). The New Annotated Sherlock Holmes, Volume III (New York: W. W. Norton, 2006). ISBN 978-0393058000 ("Klinger III")

Citations

- ^ a b c d Sutherland, John. "Sherlock Holmes, the world's most famous literary detective". British Library. Archived from the original on 28 June 2017. Retrieved 3 July 2018.

- ^ a b Haigh, Brian (20 May 2008). "A star comes to Huddersfield!". BBC. Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 25 December 2019.

- ^ a b c "Sherlock Holmes awarded title for most portrayed literary human character in film & TV". Guinness World Records. 14 May 2012. Archived from the original on 10 December 2019. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- ^ a b Rule, Sheila (5 November 1989). "Sherlock Holmes's Mail: Not Too Mysterious". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 11 March 2016. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- ^ a b Simpson, Aislinn (4 February 2008). "Winston Churchill didn't really exist, say teens". The Daily Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 30 December 2019.

- ^ Scott, C. T. (6 October 2021). "The curious incident of Sherlock Holmes's real-life secretary". The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Archived from the original on 10 October 2021. Retrieved 10 October 2021.

- ^ a b c d Armstrong, Jennifer Keishin (6 January 2016). "How Sherlock Holmes changed the world". BBC. Archived from the original on 17 February 2018. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- ^ Sova, Dawn B. (2001). Edgar Allan Poe: A to Z (Paperback ed.). Checkmark Books. pp. 162–163. ISBN 0-8160-4161-X.

- ^ Knowles, Christopher (2007). Our Gods Wear Spandex: The Secret History of Comic Book Heroes. Weiser Books. p. 67. ISBN 978-1-57863-406-4.

- ^ Conan Doyle, Arthur (1993). Lancelyn Green, Richard (ed.). The Oxford Sherlock Holmes: The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. xv.

- ^ Sims, Michael (25 January 2017). "How Sherlock Holmes Got His Name". Literary Hub. Archived from the original on 16 July 2021. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ^ Klinger III, pp. 42-44—A Study in Scarlet

- ^ Lycett, Andrew (2007). The Man Who Created Sherlock Holmes: The Life and Times of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Free Press. pp. 53–54, 190. ISBN 978-0-7432-7523-1.

- ^ Barring-Gould, William S. (1974). The Annotated Sherlock Holmes. Clarkson N. Potter, Inc. p. 8. ISBN 0-517-50291-7.

- ^ Doyle, A. Conan (1961). The Boys' Sherlock Holmes, New & Enlarged Edition. Harper & Row. p. 88.

- ^ Cauvain, Henry (2006). Peter D. O'Neill, foreword to Maximilien Heller. Glen Segell Publishers. ISBN 9781901414301. Archived from the original on 19 February 2024. Retrieved 10 November 2015.

- ^ "¿Fue Sherlock Holmes un plagio?". ABC. 22 February 2015. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 10 November 2015.

- ^ "Maximilien Holmes. How Intertextuality Influences Translation, by Sandro Maria Perna, Università degli Studi di Padova 2013/14" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 November 2018. Retrieved 10 November 2015.

- ^ "France". The Arthur Conan Doyle Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 23 June 2018. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- ^ Klinger II, p. 1432—"His Last Bow"

- ^ Klinger I, pp. 637-639—"The Greek Interpreter"

- ^ Quigley, Michael J. "Mycroft Holmes". The Official Conan Doyle Estate Ltd. Archived from the original on 27 December 2019. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- ^ Klinger I, pp. 529-531—"The Musgrave Ritual"

- ^ Klinger I, pp. 501-502—"The Gloria Scott"

- ^ Klinger III, pp. 17-18, 28—A Study in Scarlet

- ^ Birkby, Michelle. "Mrs Hudson". The Official Conan Doyle Estate Ltd. Archived from the original on 27 December 2019. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- ^ Klinger II, pp. 1692, 1705-1706—"The Adventure of the Veiled Lodger"

- ^ Klinger III, p. 217—The Sign of Four

- ^ Klinger II, pp. 1482-1483—"The Blanched Soldier"

- ^ a b Klinger II, p. 1598—"The Adventure of the Three Garridebs"

- ^ "The Reigate Squires" and "The Adventure of the Illustrious Client" are two examples.

- ^ "The Reigate Squires"

- ^ Klinger II, p. 976—"The Adventure of Black Peter"

- ^ Klinger I, pp. 561-562—"The Reigate Squires"

- ^ Klinger II, pp. 1190-1191, 1222-1225—"The Adventure of the Second Stain"

- ^ a b Klinger I, pp. 15-16—"A Scandal in Bohemia"

- ^ Klinger II, p. 1092—"The Adventure of the Golden Pince-Nez"

- ^ Klinger I, p. 299—"The Adventure of the Noble Bachelor"—there was no such position in existence at the time of the story.

- ^ The Hound of the Baskervilles (Klinger III p. 409) and "The Adventure of Black Peter" (Klinger II p. 977)

- ^ "The Adventure of the Bruce-Partington Plans", "The Naval Treaty", and after retirement, "His Last Bow".

- ^ Klinger II, p. 1581—"The Adventure of the Three Garridebs"

- ^ In "The Naval Treaty" (Klinger I p. 691), Holmes remarks that, of his last fifty-three cases, the police have had all the credit in forty-nine.

- ^ Walsh, Michael. "Professor James Moriarty". The Official Conan Doyle Estate Ltd. Archived from the original on 27 December 2019. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- ^ Klinger II, p. 1448—The Case-book of Sherlock Holmes

- ^ a b "The hounding of Arthur Conan Doyle". The Irish News. Archived from the original on 28 January 2021. Retrieved 8 October 2020.

- ^ Calamai, Peter (22 May 2013). "A Reader Challenge & Prize". The Baker Street Journal. Archived from the original on 27 May 2017. Retrieved 25 June 2018.

- ^ Klinger I, pp. 791-794—"The Adventure of the Empty House"

- ^ Klinger II, pp. 815-822

- ^ Riggs, Ransom (2009). The Sherlock Holmes Handbook. The methods and mysteries of the world's greatest detective. Philadelphia: Quirk Books. pp. 115–118. ISBN 978-1-59474-429-7.

- ^ Klinger II, pp. 1229, 1437, 1440—His Last Bow

- ^ Klinger II, p. 1189—"The Adventure of the Second Stain"

- ^ Klinger II, p. 1667—"The Adventure of the Lion's Mane"

- ^ Klinger I, p. 265—"The Adventure of the Engineer's Thumb"

- ^ Klinger III, p. 550—The Hound of the Baskervilles

- ^ Klinger I, pp. 528-529—"The Musgrave Ritual"

- ^ Klinger III, p. 481—The Hound of the Baskervilles

- ^ DK (12 November 2019). The Sherlock Holmes Book: Big Ideas Simply Explained. United Kingdom: Penguin. p. 564. ISBN 978-1-4654-9944-8.

- ^ "A Scandal in Bohemia", "The Adventure of Charles Augustus Milverton", and "The Adventure of the Illustrious Client"

- ^ a b c Klinger I, p. 502—"The Gloria Scott"

- ^ Klinger II, p. 848—"The Adventure of the Norwood Builder"

- ^ Klinger II, p. 1513—"The Adventure of the Mazarin Stone"

- ^ Klinger III, pp. 34-36—A Study in Scarlet

- ^ Klinger II, pp. 1296-1297—"The Adventure of the Red Circle"

- ^ Klinger I, p. 58—"The Red-Headed League"

- ^ Klinger III, pp. 213-214—The Sign of Four

- ^ Diniejko, Andrzej (13 December 2013). "Sherlock Holmes's Addictions". The Victorian Web. Archived from the original on 27 December 2019. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- ^ Diniejko, Andrzej (7 September 2002). "Victorian Drug Use". The Victorian Web. Archived from the original on 2 February 2020. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- ^ Dalby, J. T. (1991). "Sherlock Holmes's Cocaine Habit". Irish Journal of Psychological Medicine. 8: 73–74. doi:10.1017/S0790966700016475. ISSN 2051-6967. S2CID 142678530. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 24 September 2007.

- ^ Klinger III, pp. 215-216—The Sign of Four

- ^ Klinger II, p. 450—"The Yellow Face"

- ^ Klinger II, p. 1124—"The Adventure of the Missing Three-Quarter"

- ^ Klinger III, p. 423—The Hound of the Baskervilles. See also Klinger II, pp. 950, 1108-1109.

- ^ Klinger II, p. 1402—"The Adventure of the Devil's Foot"

- ^ Klinger II, p. 1609—"The Problem of Thor Bridge"

- ^ Klinger II, p. 971—"The Adventure of the Priory School"

- ^ "Wages and Cost of Living in the Victorian Era". The Victorian Web. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 13 March 2016.

- ^ Klinger II, p. 976—"The Adventure of Black Peter"

- ^ Liebow, Ely (1982). Dr. Joe Bell: Model for Sherlock Holmes. Popular Press. p. 173. ISBN 9780879721985. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- ^ Klinger III, p. 704—The Valley of Fear

- ^ Klinger II, pp. 1203-1204—"The Adventure of the Second Stain"

- ^ Klinger III, p. 311—The Sign of Four

- ^ Klinger II, p. 1676—"The Adventure of the Lion's Mane"

- ^ Klinger III, p. 378—The Sign of Four

- ^ Klinger II, p. 1422—"The Adventure of the Devil's Foot"

- ^ Klinger I, p. 635—"The Greek Interpreter"

- ^ Klinger II, p. 1111—"The Adventure of the Golden Pince-Nez"

- ^ Klinger II, pp. 1341-1342—"The Adventure of the Dying Detective"

- ^ Klinger II, pp. 1015-1106—"The Adventure of Charles Augustus Milverton"

- ^ Karlson, Katherine. "Irene Adler". The Official Conan Doyle Estate Ltd. Archived from the original on 27 December 2019. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- ^ Klinger I, pp. 5-6—"A Scandal in Bohemia"

- ^ Klinger I, pp. 5-40—"A Scandal in Bohemia"

- ^ a b c Klinger III, pp. 34-35—A Study in Scarlet

- ^ Klinger III, pp. 32-33—A Study in Scarlet

- ^ Klinger III, p. 650—The Valley of Fear

- ^ Klinger II, p. 1689—"The Adventure of the Lion's Mane"

- ^ Richard Lancelyn Green, "Introduction", The Return of Sherlock Holmes (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993) XXX.

- ^ Klinger III, p. 202—A Study in Scarlet

- ^ Klinger I, p. 100—"A Case of Identity"

- ^ Klinger IIII, p. 282—The Sign of Four

- ^ Klinger I, p. 73—"The Red-Headed League"

- ^ Klinger III, p. 570—The Hound of the Baskervilles

- ^ Klinger III, pp. 1333-1334, 1338-1340—"The Adventure of the Bruce-Partington Plans"

- ^ Klinger, Leslie (1999). "Lost in Lassus: The Missing Monograph". Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- ^ Klinger II, p. 888—"The Adventure of the Dancing Men"

- ^ Klinger I, p. 33—"A Scandal in Bohemia"

- ^ Klinger I, p. 216—"The Adventure of the Blue Carbuncle"

- ^ Konnikova, Maria. "How to Think Like Sherlock Holmes". Point of Inquiry. Center for Inquiry. Archived from the original on 19 December 2018. Retrieved 23 July 2017.

- ^ Klinger III, pp. 387-392—The Hound of the Baskervilles

- ^ Klinger I, pp. 450-453—"The Yellow Face"

- ^ Klinger I, pp. 201-203—"The Adventure of the Blue Carbuncle"

- ^ Klinger I, p. 9—"A Scandal in Bohemia"

- ^ Klinger III, p. 42—A Study in Scarlet

- ^ Klinger I, pp. 423-426—"The Cardboard Box"

- ^ Klinger II, pp. 864-865—"The Adventure of the Dancing Men"

- ^ Bird, Alexander (27 June 2006). "Abductive Knowledge and Holmesian Inference". In Tamar Szabo Gendler; Hawthorne, John (eds.). Oxford studies in epistemology. OUP Oxford. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-19-928590-7.

- ^ Sebeok & Umiker-Sebeok 1984, pp. 19–28, esp. p. 22

- ^ Smith, Jonathan (1994). Fact and feeling: Baconian science and the nineteenth-century literary imagination. Univ of Wisconsin Press. p. 214. ISBN 978-0-299-14354-1. Archived from the original on 19 February 2024. Retrieved 29 September 2020.

- ^ Klinger III, p. 40—A Study in Scarlet

- ^ Bennett, Bo. "Pseudo-Logical Fallacies". Logicallyfallacious.com. Logically Fallacious. Archived from the original on 31 July 2020. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- ^ Klinger I, pp. 449-471—"The Yellow Face"

- ^ "Sherlock Holmes: Pioneer in Forensic Science". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 20 December 2019. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- ^ a b Snyder, Laura J. (2004). "Sherlock Holmes: scientific detective". Endeavour. 28 (3): 104–108. doi:10.1016/j.endeavour.2004.07.007. PMID 15350761.

- ^ A Study in Scarlet, "The Adventure of Silver Blaze", "The Adventure of the Priory School", The Hound of the Baskervilles, "The Boscombe Valley Mystery"

- ^ "The Adventure of the Resident Patient", The Hound of the Baskervilles

- ^ "The Reigate Squires", "The Man with the Twisted Lip"

- ^ Klinger I, pp. 99-100—"A Case of Identity"

- ^ Klinger I, p. 578—"The Reigate Squires"

- ^ Klinger I, pp. 438-439—"The Cardboard Box"

- ^ Klinger I, p. 670—"The Naval Treaty"

- ^ Klinger II, p. 814—"The Adventure of the Empty House"

- ^ Klinger II, pp. 860-863

- ^ Schwartz, Roy (20 May 2022). "Opinion: The fictional character who changed the science of solving crime". CNN. Archived from the original on 21 May 2022. Retrieved 21 May 2022.

- ^ Klinger I, p. 30—"A Scandal in Bohemia"

- ^ Schurr, Maria (15 March 2021). "Hauntings, Dystopia and the English Outsider in Albion's Secret History". Pop Matters. Archived from the original on 30 July 2021. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^ Klinger II, p. 1545—"The Adventure of the Three Gables"

- ^ Klinger II, p. 1456—"The Adventure of the Illustrious Client"

- ^ Klinger III, p. 305—The Sign of Four. These "street Arabs" also appear briefly in A Study in Scarlet and "The Adventure of the Crooked Man".

- ^ Merritt, Russell. "The Baker Street Irregulars and Billy The Page". The Official Conan Doyle Estate Ltd. Archived from the original on 27 December 2019. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- ^ "The Guns of Sherlock Holmes". Archived from the original on 14 November 2012. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- ^ Klinger III, p. 589—The Hound of the Baskervilles

- ^ Klinger II, pp. 805-806—"The Adventure of the Empty House"

- ^ See "The Red-Headed League" and "The Adventure of the Illustrious Client".

- ^ Klinger II, p. 1050—"The Adventure of the Six Napoleons"

- ^ Klinger I, p. 449—"The Yellow Face"

- ^ Klinger I, p. 243—"The Adventure of the Speckled Band"

- ^ Klinger III, pp. 262-263—The Sign of Four

- ^ Klinger I, pp. 449-450—"The Yellow Face"

- ^ a b Klinger II, p. 915—"The Solitary Cyclist"

- ^ Klinger II, p. 916—"The Solitary Cyclist"

- ^ Klinger II, p. 791—"The Adventure of the Empty House"

- ^ "The Mystery of Baritsu". The Bartitsu Society. Archived from the original on 30 November 2018. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- ^ Kathryn Caroline Smith (2 May 2008). "Forming and Protecting the Middle-Class Victorian Ideal: Holmes and Watson" (PDF). University of North Carolina at Greensboro. University of North Carolina at Pembroke.

- ^ Nathan, Richard (18 December 2020). "Ultra-Influencers: The Two British Fictional Victorians that Changed Japan". Red Circle Authors. Archived from the original on 18 December 2020. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- ^ "Santander: who was Abbey's most famous customer?". The Telegraph. 27 May 2009. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 18 February 2020.

- ^ Stamp, Jimmy (18 July 2012). "The Mystery of 221B Baker Street". Smithsonian. Archived from the original on 23 November 2020. Retrieved 18 February 2020.

- ^ Sayers, Dorothy L. (1946). Unpopular Opinions. London: Victor Gollancz. p. 134-190.

- ^ Reed, Brian (1934). Railway Engines of the World. Oxford University Press. p. 133.

- ^ Mews News Archived 27 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Lurot Brand. Published Summer 2009. Retrieved 24 September 2013.

- ^ "Northumberland Street". Sherlockology. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- ^ Thomson, Henry Douglas (1958). The Sherlock Holmes Catalogue of the Collection in the Bars and the Grill Room and in the Reconstruction of Part of the Living Room at 221 B Baker Street. Whitbread.

- ^ "NI chemist honours Sherlock Holmes". BBC News. 16 October 2002. Archived from the original on 19 June 2018. Retrieved 19 June 2011.

- ^ "Royal Mail launches Sherlock Holmes stamps that reveal secret storylines under UV light". The Independent. 18 August 2020. Archived from the original on 1 October 2022. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

- ^ Redmond, Christopher (2009). Sherlock Holmes Handbook: Second Edition. Dundurn. p. 301. ISBN 9781770705920.

- ^ Reid, T. R. (22 September 1999). "Sherlock Holmes honored with statue near fictional London home". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 9 November 2020. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- ^ Cannon-Brookes, Peter (11 April 2017). "Irena Sedlecka". The Atelier Sale of Franta Belsky and Irena Sedlecka. Oxford: Mallams. p. 33. Archived from the original on 20 October 2021. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ^ "Monument to Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson". Dialogue of Cultures - United World. Archived from the original on 26 July 2020. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- ^ Gangelhoff, Bonnie (15 September 2017). "A small Oklahoma town finds community through public art". Southwest Art. Archived from the original on 14 November 2020. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ^ McClure, Michael (7 December 2019). "December 7, 2019: First Permanent Granite Tribute to Sherlock Holmes erected in the Americas". Baskerville Productions. Archived from the original on 26 July 2020. Retrieved 7 December 2019.

- ^ "About the Society". The Sherlock Holmes Society of London. Archived from the original on 16 December 2019. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- ^ "Origins of the BSI". The Baker Street Irregulars. 8 June 2018. Archived from the original on 27 December 2019. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- ^ "Societies and Locations". Sherlockian.net. Archived from the original on 27 December 2019. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- ^ Redmond, Christopher (2009). Sherlock Holmes Handbook: Second Edition. Dundurn Press. p. 257. ISBN 978-1-55488-446-9.