Werner von Siemens

Werner von Siemens | |

|---|---|

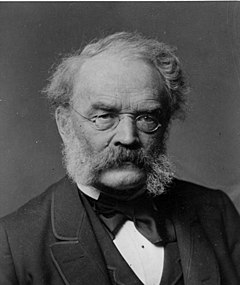

1885 portrait | |

| Born | Ernst Werner Siemens 13 December 1816 |

| Died | 6 December 1892 (aged 75) |

| Known for | Founder of Siemens AG |

| Awards | Pour le Mérite for Sciences and Arts (1886) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Electrical engineer, inventor |

Ernst Werner Siemens (von Siemens from 1888; /ˈsiːmənz/ SEEM-ənz;[1] German: [ˈziːməns, -mɛns];[2] 13 December 1816 – 6 December 1892) was a German electrical engineer, inventor and industrialist. Siemens's name has been adopted as the SI unit of electrical conductance, the siemens. He founded the electrical and telecommunications conglomerate Siemens and invented the electric tram, trolley bus, electric locomotive and electric elevator.

Biography

[edit]Early years

[edit]Ernst Werner Siemens was born in Lenthe,[3] today part of Gehrden, near Hannover, in the Kingdom of Hanover in the German Confederation, the fourth child (of fourteen) of Christian Ferdinand Siemens (31 July 1787 – 16 January 1840) and wife Eleonore Deichmann (1792 – 8 July 1839). His father was a tenant farmer of the Siemens family, an old family of Goslar, documented since 1384. Carl Heinrich von Siemens and Carl Wilhelm Siemens were his brothers.

Middle years

[edit]After finishing school, Siemens intended to study at the Bauakademie Berlin.[4] However, since his family was highly indebted and thus could not afford to pay the tuition fees, he chose to join the Prussian Military Academy's School of Artillery and Engineering, between the years 1835–1838, instead, where he received his officers training.[5] Siemens was thought of as a good soldier, receiving various medals[citation needed], and contributing to the invention of electrically-charged sea mines, which were used to combat a Danish blockade of Kiel during the First Schleswig War.[6][7]

Upon returning home from war, he chose to work on perfecting technologies that had already been established and eventually became known worldwide for his advances in various technologies. In 1843 he sold the rights to his first invention to Elkington of Birmingham.[8] Siemens invented a telegraph that used a needle to point to the right letter, instead of using Morse code.[9] Based on this invention, he founded the company Telegraphen-Bauanstalt von Siemens & Halske on 1 October 1847, with the company opening a workshop on 12 October.[10]

The company was internationalised soon after its founding. One brother of Werner represented him in England (Sir William Siemens) and another in St. Petersburg, Russia (Carl von Siemens), each earning recognition. Following his industrial career, he was ennobled in 1888, becoming Werner von Siemens. He retired from his company in 1890 and died in 1892 in Berlin.[citation needed]

The company, reorganized as Siemens & Halske AG, Siemens-Schuckertwerke and – since 1966 – Siemens AG was later led by his brother Carl, his sons Arnold, Wilhelm, and Carl Friedrich, his grandsons Hermann and Ernst and his great-grandson Peter von Siemens. Siemens AG is one of the largest electrotechnological firms in the world. The von Siemens family still owns 6% of the company shares (as of 2013) and holds a seat on the supervisory board, being the largest shareholder.[citation needed]

Later years

[edit]Apart from the pointer telegraph, Siemens made sufficient contributions to the development of electrical engineering that he became known as the founding father of the discipline in Germany. He built the world's first electric passenger train in 1879,[11] and the first electric elevator in 1880.[12] His company produced the tubes with which Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen investigated x-rays. He claimed invention of the dynamo although others invented it earlier. On 14 December 1877 he received German patent No. 2355 for an electromechanical "dynamic" or moving-coil transducer, which was adapted by A. L. Thuras and E. C. Wente for the Bell System in the late 1920s for use as a loudspeaker.[13] Wente's adaptation was issued U.S. patent 1,707,545 in 1929.

In May 1881, Siemens & Halske inaugurated the world's first electric tram service, in the Berlin suburb of Groß-Lichterfelde.[14] Siemens is also the father of the trolleybus, which he initially tried and tested on 29 April 1882, using his "Elektromote".

Personal life

[edit]He was married twice: first in 1852 to Mathilde Drumann (died 1 July 1867), the daughter of the historian Wilhelm Drumann; second in 1869 to his relative Antonie Siemens (1840–1900). His children from first marriage were Arnold von Siemens and Georg Wilhelm von Siemens, and his children from second marriage were Hertha von Siemens (1870 – 5 January 1939), married in 1899 to Carl Dietrich Harries, and Carl Friedrich von Siemens.

Siemens was an advocate of social democracy,[15] and he hoped that industrial development would not be used in favour of capitalism, stating:

A number of great factories in the hands of rich capitalists, in which "slaves of work" drag out their miserable existence, is not, therefore, the goal of the development of the age of natural science, but a return to individual labour, or where the nature of things demands it, the carrying on of common workshops by unions of workmen, who will receive a sound basis only through the general extension of knowledge and civilization, and through the possibility of obtaining cheaper capital.[16]

He also rejected the claim that science leads to materialism, stating instead:

Equally unfounded is the complaint that the study of science and the technical application of the forces of nature gives to mankind a thoroughly material direction, makes them proud of their knowledge and power, and alienates ideal endeavours. The deeper we penetrate into the harmonious action of natural forces regulated by eternal unalterable laws, and yet so thickly veiled from our complete comprehension, the more we feel on the contrary moved to humble modesty, the smaller appears to us the extent of our knowledge, the more active is our endeavour to draw more from the inexhaustible fountain of knowledge, and understanding, and the higher rises our admiration of the endless wisdom which ordains and penetrates the whole creation.[17][18][19]

Commemoration

[edit]Werner von Siemens' portrait appeared on the 20 ℛ︁ℳ︁ banknote issued by the Reichsbank from 1929 until 1939.[20] Printing ceased in 1939 but the note remained in circulation until the issue of the Deutsche Mark on 21 June 1948.

In 1923, German botanist Ignatz Urban published Siemensia, which is a monotypic genus of flowering plant from Cuba belonging to the family Rubiaceae and was named in honor of Werner von Siemens.[21]

U.S. patents

[edit]- U.S. patent 322,859 — Electric railway (21 July 1885)

- U.S. patent 340,462 — Electric railway (20 April 1886)

- U.S. patent 415,577 — Electric meter (19 November 1889)

- U.S. patent 428,290 — Electric meter (20 May 1890)

- U.S. patent 520,274 — Electric railway (22 May 1894)

- U.S. patent 601,068 — Method of and apparatus for extracting gold from its ores (22 March 1898)

See also

[edit]- Friedrich von Hefner-Alteneck—one of Siemens's aides

- Werner von Siemens Ring Award

- German inventors and discoverers

- History of electrical engineering

- Timeline of the electric motor

- Bow collector

- Dielectric barrier discharge

- Double-T armature

- Dynamo

- Electric bell

- Electric locomotive

- Electric generator

- Electromote

- Elevator

- Experimental three-phase railcar

- Microplasma

- Phase plug

- Siemens mercury unit

- Trolleybus

References

[edit]- ^ Wells, John (3 April 2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Pearson Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- ^ Wells, John C. (2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- ^ "Werner von Siemens: A dynamic, visionary entrepreneur". siemens.com Global Website. Retrieved 5 January 2024.

- ^ Werner von Siemens. "Inventor and entrepreneur : recollections of Werner von Siemens". London, England, 1966.

- ^ "HNF - Werner von Siemens (1816-1892)". www.hnf.de.

- ^ "L I F E L I N E S - Werner von Siemens" (PDF). siemens.com. Siemens Historical Institute, L I F E L I N E S – Volume 5. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- ^ "Werner Siemens' battle for Friedrichsort Fortress in 1848". Burgerbe.de. 2 November 2014. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- ^ Schwartz & McGuinness Einstein for Beginners Icon Books 1992

- ^ "Courage and ingenuity – Siemens' success story begins with the pointer telegraph". Siemens Historical Institute. Retrieved 5 June 2019.

- ^ "The year is 1847". Siemens Historical Institute. Retrieved 5 June 2019.

- ^ E. Hoffmann: Telegraphy and Electrical Engineering at the Berlin Trade Exhibition in 1879. Reprint from: Archiv für Post und Telegraphie 1879, No. 14. Berlin 1879. (Quote p. 17–19 at technik-in-bayern.de)

- ^ "The History of Elevators From Top to Bottom". ThoughtCo.

- ^ Ed. M. D. Fagen, "A History of Engineering and Science in the Bell System: The Early Years", Bell Laboratories, 1975, p. 183.

- ^ "Werner von Siemens". siemens.com Global Website. Retrieved 14 August 2021.

- ^ Werner von Siemens (1893). Personal Recollections of Werner Von Siemens. Asher. p. 373

- ^ D. Appleton., (1887). Popular Science Monthly, Volume 30.

- ^ Bonnier Corporation. Popular Science Apr 1887,Vol. 30, No. 46. ISSN 0161-7370. pp. 814–820

- ^ Werner von Siemens (1895). Scientific & technical papers of Werner von Siemens. J. Murray. p. 518

- ^ A similar account is given in Siemens, Werner von (1893). Personal Recollections, p. 373: "I also tried in my lecture to show that the study of the physical sciences in its further progress and general diffusion would not brutalize men and divert them from ideal aspirations, but on the contrary would lead them to humble admiration of the incomprehensible wisdom pervading the whole creation and must therefore ennoble and improve them."

- ^ "P-181". banknote.ws.

- ^ "Siemensia Urb. | Plants of the World Online | Kew Science". Plants of the World Online. Retrieved 19 May 2021.

Further reading

[edit]- Shaping the Future. The Siemens Entrepreneurs 1847–2018. Ed. Siemens Historical Institute, Hamburg 2018, ISBN 978-3-86774-624-3.

- Werner von Siemens, Lebenserinnerungen, Berlin, 1892 (reprinted as Mein Leben, Zeulenroda, 1939).

- Werner von Siemens, Scientific & Technical Papers of Werner von Siemens. Vol. 1: Scientific Papers and Addresses, London, 1892; Vol. 2: Technical Papers, London, 1895.

- Sigfrid von Weiher, Werner von Siemens, A Life in the Service of Science, Technology and Industry, Göttingen, 1975.

- Wilfried Feldenkirchen, Werner von Siemens, Inventor and International Entrepreneur. Columbus, Ohio, 1994.

- Nathalie von Siemens, A Brimming Spirit. Werner von Siemens in Letters. A Modern Entrepreneurial History, Murmann Publishers, 2016, ISBN 978-3-86774-562-8.

- Lifelines: Werner von Siemens, Vol. 5, ed. Siemens Historical Institute, Berlin 2016

External links

[edit]- Biography, Siemens Corporate Archives

- Loudspeaker History (U. of San Diego)

- Short biography and bibliography in the Virtual Laboratory of the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- . Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.

- Newspaper clippings about Werner von Siemens in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- Werner von Siemens

- 1816 births

- 1892 deaths

- Burials at Stahnsdorf South-Western Cemetery

- 19th-century German engineers

- German company founders

- German industrialists

- 19th-century German inventors

- 19th-century German businesspeople

- German electrical engineers

- German railway mechanical engineers

- German untitled nobility

- Members of the Prussian Academy of Sciences

- Members of the Prussian House of Representatives

- People from Gehrden

- People from the Kingdom of Hanover

- Recipients of the Pour le Mérite (civil class)

- Engineers from Lower Saxony

- Siemens family

- Sustainable transport pioneers