Forbes

| |

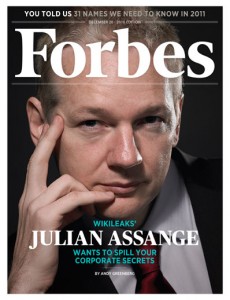

The December 20, 2010, cover of Forbes, featuring WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange | |

| Chairman / Editor-in-chief | Steve Forbes |

|---|---|

| Editor | Randall Lane[1] |

| Categories | Business magazine |

| Frequency | Twice quarterly |

| Publisher | Forbes Media |

| Total circulation (2023) | 514,184[2] |

| Founder | B. C. Forbes |

| First issue | September 15, 1917 |

| Company | Integrated Whale Media Investments |

| Country | United States |

| Based in | Jersey City, New Jersey, U.S. |

| Language | English |

| Website | forbes.com |

| ISSN | 0015-6914 |

| OCLC | 6465733 |

Forbes (/fɔːrbz/) is an American business magazine founded by B. C. Forbes in 1917 and owned by Hong Kong–based investment group Integrated Whale Media Investments since 2014.[3][4] Its chairman and editor-in-chief is Steve Forbes.[5] The company is based in Jersey City, New Jersey. Sherry Phillips was slated to become the new CEO at Forbes on January 1, 2025.[6]

Published eight times per year, Forbes features articles on finance, industry, investing, and marketing topics. It also reports on related subjects such as technology, communications, science, politics, and law. It has an international edition in Asia as well as editions produced under license in 27 countries and regions worldwide. The magazine is known for its lists and rankings, including its lists of the richest Americans (the Forbes 400), of 30 notable people under the age of 30, of America's wealthiest celebrities, of the world's top companies (the Forbes Global 2000), of the world's most powerful people, and of the world's billionaires.[7] The motto of Forbes magazine is "Change the World".[8]

Company history

[edit]

B. C. Forbes, a financial columnist for the Hearst papers, and his partner Walter Drey, the general manager of the Magazine of Wall Street,[9] founded Forbes magazine on September 15, 1917.[10][11] Forbes provided the money and the name and Drey provided the publishing expertise. The original name of the magazine was Forbes: Devoted to Doers and Doings.[9] Drey became vice-president of the B.C. Forbes Publishing Company,[12] while B.C. Forbes became editor-in-chief, a post he held until his death in 1954. B.C. Forbes was assisted in his later years by his two eldest sons, Bruce Charles Forbes (1916–1964) and Malcolm Forbes (1919–1990).

Bruce Forbes took over after his father's death, and his strengths lay in streamlining operations and developing marketing.[10] During his tenure, from 1954 to 1964, the magazine's circulation nearly doubled.[10]

On Bruce's death, his brother Malcolm Forbes became president and chief executive officer of Forbes, and editor-in-chief of Forbes magazine.[13] Between 1961 and 1999 the magazine was edited by James Michaels.[14] In 1993, under Michaels, Forbes was a finalist for the National Magazine Award.[15] In 2006, an investment group Elevation Partners that includes rock star Bono bought a minority interest in the company with a reorganization, through a new company, Forbes Media LLC, in which Forbes Magazine and Forbes.com, along with other media properties, is now a part.[13][16] A 2009 New York Times report said: "40 percent of the enterprise was sold... for a reported $300 million, setting the value of the enterprise at $750 million." Three years later, Mark M. Edmiston of AdMedia Partners observed, "It's probably not worth half of that now."[17] It was later revealed that the price had been US$264 million.[18]

In 2021, Forbes Media reported a return to profit, with revenue increasing by 34 percent to $165 million. Much of the revenue growth was attributed to Forbes' consumer business, which was up 83 percent year-over-year.[19] CEO Mike Federle says that Forbes is built on an audience and business scale with 150 million consumers.[20]

Sale of headquarters

[edit]In January 2010, Forbes reached an agreement to sell its headquarters building on Fifth Avenue in Manhattan to New York University; terms of the deal were not publicly reported, but Forbes was to continue to occupy the space under a five-year sale-leaseback arrangement.[21] The company's headquarters moved to the Newport section of downtown Jersey City, New Jersey, in 2014.[22][23]

Sale to Integrated Whale Media (51% stake)

[edit]In November 2013, Forbes Media, which publishes Forbes magazine, was put up for sale.[24] This was encouraged by minority shareholders Elevation Partners. Sale documents prepared by Deutsche Bank revealed that the publisher's 2012 earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization was US$15 million.[25] Forbes reportedly sought a price of US$400 million.[25] In July 2014, the Forbes family bought out Elevation and then Hong Kong-based investment group Integrated Whale Media Investments purchased a 51 percent majority of the company.[3][4][18]

In 2017, Isaac Stone Fish, a senior fellow of the Asia Society, wrote in The Washington Post that "Since that purchase, there have been several instances of editorial meddling on stories involving China that raise questions about Forbes magazine's commitment to editorial independence."[26]

Failed SPAC merger and sale

[edit]On August 26, 2021, Forbes announced plans to go public via a merger with a special-purpose acquisition company called Magnum Opus Acquisition, and to trade on the New York Stock Exchange as FRBS.[27] In February 2022, it was announced that Cryptocurrency exchange Binance would acquire a $200 million stake in Forbes as a result of the SPAC flotation.[28][29] In June 2022, the company terminated its SPAC merger citing unfavorable market conditions.[30]

In August 2022, the company announced that it was exploring a sale of its business.[31] In May 2023, it was announced that billionaire Austin Russell, founder of Luminar Technologies, agreed to acquire an 82 percent stake in a deal valuing the company at $800 million.[32] His majority ownership was to include the remaining portion of the company owned by the Forbes family which was not previously sold to Integrated Whale Media.[33][34] The transaction attracted scrutiny by the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States. Russell denied reports that Russian businessman Magomed Musaev was involved in the transaction.[32] In November 2023, the deal collapsed, as Russell was unable to put together the necessary funds.[35]

Other publications

[edit]Apart from Forbes and its lifestyle supplement, Forbes Life, the magazine has 42 international editions covering 69 countries:[36]

- Forbes Africa

- Forbes Afrique (Francophone Africa)

- Forbes África Lusófona (Lusophone Africa)

- Forbes Argentina

- Forbes Australia

- Forbes Austria

- Forbes Brazil

- Forbes Bulgaria

- Forbes Central America

- Forbes Chile

- Forbes China

- Forbes Colombia

- Forbes Cyprus

- Forbes Czech Republic

- Forbes Dominican Republic

- Forbes Ecuador

- Forbes En Español

- Forbes España (Spain)

- Forbes France

- Forbes Georgia

- Forbes Greece

- Forbes Hungary

- Forbes India

- Forbes Israel

- Forbes Italy

- Forbes Japan

- Forbes Kazakhstan

- Forbes Korea

- Forbes Mexico

- Forbes Middle East

- Forbes Paraguay[37]

- Forbes Peru

- Forbes Poland

- Forbes Portugal

- Forbes Romania

- Forbes Slovensko (Slovakia)

- Forbes Srbija (Serbia)

- Forbes Switzerland

- Forbes Thailand

- Forbes Ukraine

- Forbes Uruguay

- Forbes Vietnam

Ceased publication

[edit]- Forbes Baltics

- Forbes Estonia

- Forbes Indonesia

- Forbes Latvia

- Forbes Lithuania

- Forbes Monaco

- Forbes Russia

Chairman / Editor-in-chief Steve Forbes and his magazine's writers offer investment advice on the weekly Fox TV show Forbes on Fox and on Forbes on Radio. Other company groups include Forbes Conference Group, Forbes Investment Advisory Group and Forbes Custom Media. From the 2009 Times report: "Steve Forbes recently returned from opening up a Forbes magazine in India, bringing the number of foreign editions to 10." In addition, that year the company began publishing ForbesWoman, a quarterly magazine published by Steve Forbes's daughter, Moira Forbes, with a companion Web site.[17]

The company formerly published American Legacy magazine as a joint venture, although that magazine separated from Forbes on May 14, 2007.[38]

The company also formerly published American Heritage and Invention & Technology magazines. After failing to find a buyer, Forbes suspended publication of these two magazines as of May 17, 2007.[39] Both magazines were purchased by the American Heritage Publishing Company and resumed publication as of the spring of 2008.[40] Forbes has published the Forbes Travel Guide since 2009.[41]

In 2013, Forbes licensed its brand to Ashford University, and assisted with the launch of the Forbes School of Business & Technology.[42] CEO Mike Federle justified the licensing in 2018, stating that "Our licensing business is almost a pure-profit business, because it's an annual annuity."[43] Forbes would launch limited promotions for the school in limited issues. Forbes has never formally endorsed the school.

On January 6, 2014, Forbes magazine announced that, in partnership with app creator Maz, it was launching a social networking app called "Stream". Stream allows Forbes readers to save and share visual content with other readers and discover content from Forbes magazine and Forbes.com within the app.[44]

Forbes.com

[edit]David Churbuck founded Forbes's web site in 1996. The site uncovered Stephen Glass's journalistic fraud in The New Republic in 1998, an article that drew attention to internet journalism.[45] At the peak of media coverage of alleged Toyota sudden unintended acceleration in 2010, it exposed the California "runaway Prius" as a hoax, as well as running five other articles by Michael Fumento challenging the entire media premise of Toyota's cars gone bad. The website (like the magazine) publishes lists focusing on billionaires and their possessions, especially real estate.[46][47][20]

Forbes.com is part of Forbes Digital, a division of Forbes Media LLC. Forbes's holdings include a portion of RealClearPolitics. Together these sites reach more than 27 million unique visitors each month. Forbes.com employs the slogan "Home Page for the World's Business Leaders" and claimed, in 2006, to be the world's most widely visited business web site.[48] The 2009 Times report said that, while "one of the top five financial sites by traffic [throwing] off an estimated $70 million to $80 million a year in revenue, [it] never yielded the hoped-for public offering".[17]

Forbes.com uses a contributor network in which a wide network of freelancers ("contributors") writes and publishes articles directly on the website.[49] Contributors are paid based on traffic to their respective Forbes.com pages; the site has received contributions from over 2,500 individuals, and some contributors have earned over US$100,000, according to the company.[49] The contributor system has been criticized for enabling "pay-to-play journalism" and the repackaging of public relations material as news.[50] Forbes currently allows advertisers to publish blog posts on its website alongside regular editorial content through a program called BrandVoice, which accounts for more than 10 percent of its digital revenue.[51] In July 2018 Forbes deleted an article by a contributor who argued that libraries should be closed, and Amazon should open bookstores in their place.[52]

As of 2019 the company published 100 articles each day produced by 3,000 outside contributors who were paid little or nothing.[53] This business model, in place since 2010,[54] "changed their reputation from being a respectable business publication to a content farm", according to Damon Kiesow, the Knight Chair in digital editing and producing at the University of Missouri School of Journalism.[53] Similarly, Harvard University's Nieman Lab deemed Forbes "a platform for scams, grift, and bad journalism" as of 2022.[50]

In 2017 the website blocked internet users using ad blocking software from accessing articles, demanding that the website be put on the ad blocking software's whitelist before access was granted.[55] Forbes argued that this is done because customers using ad blocking software do not contribute to the site's revenue. Malware attacks have been noted to occur from the Forbes site.[56]

Forbes won the 2020 Webby People's Voice Award for Business Blog/Website.[57]

Forbes8

[edit]In November 2019, Forbes launched a streaming platform Forbes8, highlighting notable entrepreneurs and sharing business tips.[58][59][60] In 2020, the network announced the release of several documentary series including Forbes Rap Mentors, Driven Against the Odds, Indie Nation and Titans on the Rocks.[61][62]

See also

[edit]- Forbes 30 Under 30

- Forbes 400

- Forbes 500

- Forbes Global 2000

- The World's Billionaires

- World's 100 Most Powerful Women

- World's Most Powerful People

References

[edit]- ^ Romenesko, Jim (August 9, 2011). "Randall Lane returns to Forbes as editor". Poynter.org. Archived from the original on February 22, 2014.

- ^ "Consumer Magazines". Alliance for Audited Media. Archived from the original on July 31, 2024.

- ^ a b "Forbes Media Agrees To Sell Majority Stake to a Group of International Investors To Accelerate The Company's Global Growth". Forbes (Press release). July 18, 2014. Retrieved July 24, 2015.

- ^ a b "Forbes Sells to Hong Kong Investment Group". Recode. July 18, 2014. Archived from the original on January 24, 2017. Retrieved August 27, 2018.

- ^ Silva, Emma (November 30, 2017). "Mike Federle Succeeds Mike Perlis As CEO Of Forbes". Folio.

- ^ "Forbes Media names Main Line resident and Delco native next CEO".Philadelphia Business Journal, Dec 11, 2024

- ^ Delbridge, Emily (November 21, 2019). "The 8 Best Business Magazines of 2020". The Balance Small Business. New York City: Dotdash. Best for Lists: Forbes. Retrieved February 8, 2020.

- ^ McClellan, Steve (October 24, 2012). "'Forbes' Launches New Tagline, Brand Campaign". MediaPost Communications. Retrieved January 24, 2020.

- ^ a b Praneeth (July 6, 2007). "Notes of a Business Quizzer: Forbes". Retrieved August 27, 2018.

- ^ a b c Gorman, Robert F. (ed.) (2007) "September 15, 1917: Forbes Magazine is founded" The Twentieth Century, 1901–1940 (Volume III) Salem Press, Pasadena, California, pp. 1374–1376 [1375], ISBN 978-1-58765-327-8

- ^ "Media Kit 2013" (PDF). Forbes Middle East. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 5, 2014. Retrieved September 18, 2014.

- ^ Commerce and Industry Association of New York (November 18, 1922) "The Association Prepares for New Demands: The Volunteer Workers" Greater New York: Bulletin of the Merchants' Association of New York Commerce and Industry Association of New York City, p. 6, OCLC 2447287

- ^ a b 'Forbes Announce Elevation Partners Investment in Family Held Company' Archived August 13, 2006, at the Wayback Machine Elevation Partners press release, August 6, 2006.

- ^ Pérez-Peña, Richard (October 4, 2007). "James Michaels, Longtime Forbes Editor, Dies at 86". The New York Times. Retrieved January 5, 2008.

- ^ "National Magazine Awards Database". Archived from the original on May 26, 2011. Retrieved January 5, 2008.

- ^ "NussbaumOnDesign Bono Buys into Forbes, Launches Product Red in US and Expands His Brand". Bloomberg BusinessWeek. Archived from the original on August 9, 2006. Retrieved January 5, 2008.

- ^ a b c Carr, David (June 14, 2009). "Even Forbes is Pinching Pennies". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 1, 2012. Retrieved June 15, 2009.

- ^ a b Trachtenberg, Jeffrey A (July 19, 2014). "Forbes sold to Asian investors". MarketWatch. Market Watch, Inc. Archived from the original on July 20, 2014. Retrieved June 18, 2017.

- ^ Norris, Ashley (December 1, 2021). "Forbes reports a return to profit in 2021". FIPP. Retrieved July 25, 2024.

- ^ a b "Forbes Business Model | How does Forbes Make Money?". StartupTalky. July 17, 2022. Retrieved July 25, 2024.

- ^ "Forbes Sells Building to N.Y.U." New York Times Media Decoder. January 7, 2010. Retrieved February 5, 2013.

- ^ Schneider, Mike (December 18, 2014). "Forbes Moves Across the Hudson to Jersey City". WNET – NJTV. Retrieved June 14, 2015.

- ^ "Forbes moving into Jersey City offices on Monday, report says". The Jersey Journal. December 11, 2014. Retrieved June 14, 2015.

- ^ Haughney, Christine; Gelles, David (November 15, 2013). "Forbes Says It Is for Sale". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 16, 2013. Retrieved November 25, 2013.

- ^ a b Doctor, Ken (January 16, 2014). "The Newsonomics of Forbes' real performance and price potential". Nieman Lab.

- ^ Fish, Isaac Stone (December 14, 2017). "Chinese ownership is raising questions about the editorial independence of a major U.S. magazine". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on December 15, 2017. Retrieved November 22, 2020.

When a Chinese company buys a major American magazine, does the publication censor its coverage of China? There is only one example so far, and the results are discouraging. In 2014, a Hong Kong-based investment group called Integrated Whale Media purchased a majority stake in Forbes Media, one of the United States' best-known media companies. It's hard to demonstrate causality in such cases. But since that purchase, there have been several instances of editorial meddling on stories involving China that raise questions about Forbes magazine's commitment to editorial independence.

- ^ Burtsztynsky, Jessica (August 26, 2021). "Forbes announces plan to go public via SPAC". CNBC. Retrieved August 26, 2021.

- ^ Wilson, Tom (February 10, 2022). "Crypto exchange Binance to invest $200 mln in U.S. media firm Forbes". Reuters.

- ^ Osipovich, Alexander (February 10, 2022). "Crypto Exchange Binance to Invest $200 Million in Forbes". Wall Street Journal.

- ^ Ramkumar, Amrith (June 1, 2022). "SeatGeek and Forbes Nix SPAC Deals During Market Pullback". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ Mullin, Benjamin; Hirsch, Lauren (August 2, 2022). "Forbes Explores Sale After SPAC Deal Collapses". The New York Times.

- ^ a b "Russian tycoon claims he is behind Forbes purchase, audiotapes show". The Washington Post. October 20, 2023. Retrieved October 22, 2023.

- ^ "Forbes to be acquired by Luminar Technologies' Austin Russell". Axios. May 12, 2023. Retrieved December 22, 2023.

- ^ Bruell, Alexandra (May 12, 2023). "Automotive Tech Billionaire Austin Russell to Acquire Majority Stake in Forbes". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ Fischer, Sara (November 21, 2023). "Forbes deal dead as Austin Russell fails to raise cash by deadline". Axios.

- ^ "DocSend - Simple, intelligent, modern content sending". DocSend. Retrieved October 30, 2024.

- ^ "Forbes anuncia su llegada a Paraguay" [Forbes announces its arrival in Paraguay]. Última Hora (in Spanish). May 2, 2024. Archived from the original on May 3, 2024. Retrieved August 2, 2024.

- ^ "With The May 14 Announced Separation: Twelve-Year-Old "American Legacy"/"Forbes" Partnership Was Mutually Beneficial". Archived from the original on September 3, 2014. Retrieved September 1, 2014.

- ^ McGrath, Charles (May 17, 2007). "Magazine Suspends Its Run in History". The New York Times.

- ^ "Thank You for Your Feedback on the American Heritage Winter 2008 Issue". American Heritage. Archived from the original on December 30, 2010.

- ^ Powell, Laura (April 24, 2018). "An Inside Look at the Forbes Travel Guide". Skift. Retrieved July 25, 2024.

- ^ "Forbes School of Business & Technology Board of Advisors". University of Arizona Global Campus. Retrieved April 22, 2021.

- ^ Patel, Sahil (December 21, 2018). "Amid media doom and gloom, Forbes says revenue was up and profits highest in a decade". Digiday. Retrieved May 12, 2019.

- ^ "Forbes Is The First Magazine To Launch Its Own Social Network With "Stream"". Forbes. January 6, 2014. Archived from the original on October 7, 2023.

- ^ "Hello, My Name Is Stephen Glass, and I'm Sorry". The New Republic. ISSN 0028-6583. Retrieved May 16, 2024.

- ^ "Jobs: Motley to Leave Time Inc., Plus More Job-Hopping Fun". Gawker. Archived from the original on February 18, 2008. Retrieved January 5, 2008.

- ^ Tognini, Giacomo. "The Richest Real Estate Billionaires In America 2023". Forbes. Retrieved July 25, 2024.

- ^ Edmonston, Peter (August 28, 2006). "At Forbes.com, Lots of Glitter but Maybe Not So Many Visitors". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 16, 2012. Retrieved May 2, 2011.

- ^ a b Bartlett, Rachel (September 26, 2013). "The Forbes contributor model: Technology, feedback and incentives". journalism.co.uk. Retrieved October 13, 2013.

- ^ a b Benton, Joshua (February 9, 2022). "An incomplete history of Forbes.com as a platform for scams, grift, and bad journalism". Nieman Lab. Retrieved August 22, 2023.

- ^ "Forbes gives advertisers an editorial voice". emedia. Archived from the original on November 9, 2013.

- ^ Weissman, Cale (July 23, 2018). "Forbes deleted its controversial article about Amazon replacing libraries". Fast Company.

- ^ a b Hsu, Tiffany (July 19, 2019). "Jeffrey Epstein pushed a new narrative; these sites published it". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 7, 2023. Retrieved August 22, 2023.

- ^ Sonderman, Jeff (May 29, 2012). "What the Forbes model of contributed content means for journalism". Poynter. Retrieved August 22, 2023.

- ^ Bloomberg, Jason. "Ad Blocking Battle Drives Disruptive Innovation". Forbes. Retrieved April 14, 2017.

- ^ Hruska, Joel. "Forbes forces readers to turn off ad blockers, promptly serves malware". Extreme Tech. Retrieved April 14, 2017.

- ^ Kastrenakes, Jacob (May 20, 2020). "Here are all the winners of the 2020 Webby Awards". The Verge. Retrieved May 22, 2020.

- ^ "Forbes8". Inc.

- ^ Releases, Forbes Press. "Forbes8, Forbes' On-Demand Video Network For Entrepreneurs, Debuts New Slate Of Original Content". Forbes. Retrieved August 5, 2020.

- ^ Kene-Okafor, Tage (May 25, 2020). "Forbes8 launches digital startup accelerator, calls for applications". Techpoint Africa. Retrieved August 5, 2020.

- ^ "Forbes8 Original Series: 6 icons of entrepreneurship show you how to become your own boss". Grit Daily News. October 23, 2019. Retrieved August 5, 2020.

- ^ "Forbes Councils". Forbes. Retrieved February 9, 2022.

Further reading

[edit]- Merid, Fevin (2023) "Big Business: The disarray and discontent at Forbes" Columbia Journalism Review [1]

- Benton, Joshua (2022) "An incomplete history of Forbes.com as a platform for scams, grift, and bad journalism" NiemanLabs [2]

- Forbes, Malcolm S. (1973). Fact and Comment. Knopf, New York, ISBN 0-394-49187-4; twenty-five years of the editor's columns from Forbes

- Grunwald, Edgar A. (1988). The Business Press Editor. New York University Press, New York, ISBN 0-8147-3016-7

- Holliday, Karen Kahler (1987). A Content Analysis of Business Week, Forbes and Fortune from 1966 to 1986. Master's of Journalism thesis from Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, 69 pages, OCLC 18772376, available on microfilm

- Kohlmeier, Louis M.; Udell, Jon G. and Anderson, Laird B. (eds.) (1981). Reporting on Business and the Economy. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, ISBN 0-13-773879-X

- Kurtz, Howard (2000). The Fortune Tellers: Inside Wall Street's Game of Money, Media, and Manipulation. Free Press, New York, ISBN 0-684-86879-2

- Pinkerson, Stewart (2011). The Fall of the House of Forbes: The Inside Story of the Collapse of a Media Empire. New York City: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0312658595.

- Tebbel, John William and Zuckerman, Mary Ellen (1991). The Magazine in America, 1741–1990. Oxford University Press, New York, ISBN 0-19-505127-0

- Parsons, D. W. (1989). The Power of the Financial Press: Journalism and Economic Opinion in Britain and America. Rutgers University Press, New Jersey, ISBN 0-8135-1497-5

External links

[edit]- Forbes

- 1917 establishments in the United States

- Magazines established in 1917

- Business magazines published in the United States

- Biweekly magazines published in the United States

- Companies based in Jersey City, New Jersey

- Magazines published in New Jersey

- Mass media in Hudson County, New Jersey

- 2014 mergers and acquisitions