Historic centre of Córdoba

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

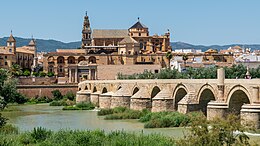

Views of the Historic centre of Córdoba from the Guadalquivir River. | |

| Location | Córdoba, Andalusia, Spain |

| Includes | Cathedral of Córdoba, Roman bridge of Córdoba, Calahorra Tower, Alcázar de los Reyes Cristianos, San Basilio, Córdoba, Roman walls of Córdoba, Puerta de Almodóvar, Caliphal Baths, Episcopal Palace of Cordoba, San Sebastián Hospital |

| Criteria | Cultural: (i), (ii), (iii), (iv) |

| Reference | 313bis |

| Inscription | 1984 (8th Session) |

| Extensions | 1994 |

| Coordinates | 37°52′45.1″N 4°46′47″W / 37.879194°N 4.77972°W |

The historic centre of Córdoba, Spain is one of the largest of its kind in Europe. In 1984, UNESCO registered the Mosque–Cathedral of Córdoba as a World Heritage Site. A decade later, it expanded the inscription to include much of the old town.[1] The historic centre has a wealth of monuments preserving large traces of Roman, Islamic, and Christian times.

Historical background

[edit]First a Carthaginian township, Córdoba was captured by the Romans in 206 BC, soon becoming the capital of Hispania Citerior with fine buildings and imposing fortifications. In the 6th century, with the crumbling of the Roman Empire, the city fell to the Visigoths until the beginning of the 8th century when it was conquered by the Moors. In 716, Córdoba became a provincial capital and, in 766, capital of the Muslim emirate of al-Andalus. By the 10th century, as the Caliphate of Córdoba it had become one of the most advanced cities in the world, recognized for its culture, learning and religious tolerance. In addition to a huge library, the city enclosed over 300 mosques and a multitude of palaces and administrative buildings.[2][3]

In 1236, King Ferdinand III took the city, built new defences and converted the Grand Mosque into a cathedral. The Christian city grew up around the cathedral with palaces, churches, and a fortress. Although the city lost its political significance under Christian rule, it continued to play an important role in commerce thanks to the nearby Sierra Morena copper mines.[2][3]

Geographic boundaries

[edit]

The historic centre as defined by UNESCO comprises the buildings and narrow winding streets around the cathedral. It is bordered on the south by the River Guadalquivir so as to include the Roman Bridge and the Calahorra Tower, on the east by the Calle San Fernando, and on the north by the commercial centre. To the west, it includes the Alcázar and the San Basilio district.[3]

Monuments

[edit]Evidence of the Roman period can be seen in the 16-span bridge over the Guadalquivir, the mosaics in the Alcázar, the columns of the Roman temple, and the remains of the Roman walls. In addition to the Caliphal Baths, the Moorish influence in the city's design is evident in the Alcázar gardens adjacent to the former Grand Mosque. Minarets from the period survive in the churches of Santiago, San Lorenzo, San Juan and the Santa Clara Hermitage. The Jewish presence during Muslim rule can be seen in the La Judería district in which the synagogue was used until 1492.[3]

The Alcázar, originally a Moorish castle, was adapted to serve as a residence for the Christian kings in the 14th century while the Calahorra Tower, built by the Almohads, was comprehensively reworked by King Henry II in 1369.[4] The little Chapel of San Bartolomé was completed in the Gothic-Mudéjar style in 1410. Originally a church, the former San Sebastián Hospital, now the Congress Centre, was completed in 1516 in a combination of Gothic, Mudéjar and Renaissance styles.[5] Other churches from the period include San Nicolás and San Francisco.[3]

There are also a number of important 16th-century buildings including the San Pelagio Seminary, the Puerta del Puente, and the Palacio del Marqués de la Fuensanta del Valle designed by Hernán Ruiz.[6] Also of note is the 18th-century Hospital del Cardenal Salazar with its Baroque facade.[7]

Other historic monuments in the old town include the Episcopal Palace built on the remains of the former Visigoth palace and now the Diocesan Fine Arts Museum,[8] and the Royal Stables built by King Philip II in 1570 as part of the Alcázar.[9]

Jewish Cordoba

[edit]Cordoba had been a seat of Jewish life in Andalusia for centuries.[citation needed] The Rambam (Maimonides), who was one of the most influential medieval Rabbis, was a notable resident of the town. There is a Historic Jewish Quarter, from the Medieval Era, that houses one of the oldest synagogues of the world; the Cordoba synagogue (built 1314-15).[10]

Gallery

[edit]-

San Bartolome Chapel

-

San Nicolás's Church

-

Former San Sebastián Hospital

-

Roman mosaic

-

Roman columns

References

[edit]- ^ "Historic Centre of Cordoba". UNESCO. Retrieved 29 December 2013.

- ^ a b "Córdoba en la Historia" (in Spanish). Córdoba: Patrimonio de la Humanidad. Archived from the original on 8 November 2013. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- ^ a b c d e "Historic Centre of Cordoba". UNESCO. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- ^ "Torre de la Calahorra". Córdoba24. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- ^ "El Hospital de San Sebastián" (in Spanish). Artencordoba.com. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- ^ "Conservatorio Superior de Música Rafael Orozco de Córdoba" (in Spanish). Gobierno de España. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- ^ "Hospital del Cardenal Salazar, Córdob" (in Spanish). Córdoba: ciudad de encuentro. Archived from the original on 29 December 2015. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- ^ "Episcopal Palace". Córdoba: ciudad de encuentro. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- ^ "Royal Stables". Córdoba: ciudad de encuentro. Archived from the original on 13 March 2016. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- ^ https://omeka.library.american.edu/s/infinite-geometries/page/synagogue [bare URL]