Idolatry

Idolatry is the worship of an idol as though it were a deity.[1][2][3] In Abrahamic religions (namely Judaism, Samaritanism, Christianity, Islam, and the Baháʼí Faith) idolatry connotes the worship of something or someone other than the Abrahamic God as if it were God.[4][5] In these monotheistic religions, idolatry has been considered as the "worship of false gods" and is forbidden by texts such as the Ten Commandments.[4] Other monotheistic religions may apply similar rules.[6]

For instance, the phrase false god is a derogatory term used in Abrahamic religions to indicate cult images or deities of non-Abrahamic Pagan religions, as well as other competing entities or objects to which particular importance is attributed.[7] Conversely, followers of animistic and polytheistic religions may regard the gods of various monotheistic religions as "false gods" because they do not believe that any real deity possesses the properties ascribed by monotheists to their sole deity. Atheists, who do not believe in any deities, do not usually use the term false god even though that would encompass all deities from the atheist viewpoint. Usage of this term is generally limited to theists, who choose to worship some deity or deities, but not others.[4]

In many Indian religions, which include Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism, idols (murti) are considered as symbolism for the absolute but not the Absolute,[8] or icons of spiritual ideas,[8][9] or the embodiment of the divine.[10] It is a means to focus one's religious pursuits and worship (bhakti).[8][11][9] In the traditional religions of Ancient Egypt, Greece, Rome, Africa, Asia, the Americas and elsewhere, the reverence of cult images or statues has been a common practice since antiquity, and idols have carried different meanings and significance in the history of religion.[7][1][12] Moreover, the material depiction of a deity or more deities has always played an eminent role in all cultures of the world.[7]

The opposition to the use of any icon or image to represent ideas of reverence or worship is called aniconism.[13] The destruction of images as icons of veneration is called iconoclasm,[14] and this has long been accompanied with violence between religious groups that forbid idol worship and those who have accepted icons, images and statues for veneration.[15][16] The definition of idolatry has been a contested topic within Abrahamic religions, with many Muslims and most Protestant Christians condemning the Catholic and Eastern Orthodox practice of venerating the Virgin Mary in many churches as a form of idolatry.[17][18]

The history of religions has been marked with accusations and denials of idolatry. These accusations have considered statues and images to be devoid of symbolism. Alternatively, the topic of idolatry has been a source of disagreements between many religions, or within denominations of various religions, with the presumption that icons of one's own religious practices have meaningful symbolism, while another person's different religious practices do not.[19][20]

Etymology and nomenclature

[edit]

The term idolatry comes from the Ancient Greek word eidololatria (εἰδωλολατρία), which itself is a compound of two words: eidolon (εἴδωλον "image/idol") and latreia (λατρεία "worship", related to λάτρις).[21] The word eidololatria thus means "worship of idols", which in Latin appears first as idololatria, then in Vulgar Latin as idolatria, therefrom it appears in 12th century Old French as idolatrie, which for the first time in mid 13th century English appears as "idolatry".[22][23]

Although the Greek appears to be a loan translation of the Hebrew phrase avodat elilim, (עבודת אלילים) which is attested in rabbinic literature (e.g., bChul., 13b, Bar.), the Greek term itself is not found in the Septuagint, Philo, Josephus, or in other Hellenistic Jewish writings.[citation needed] The original term used in early rabbinic writings is oved avodah zarah (AAZ, worship in strange service, or "pagan"), while avodat kochavim umazalot (AKUM, worship of planets and constellations) is not found in its early manuscripts.[24] The later Jews used the term עֲבוֹדָה זָרָה, avodah zarah, meaning "foreign worship".[25]

Idolatry has also been called idolism,[26] iconolatry[27] or idolodulia in historic literature.[28]

Prehistoric and ancient civilizations

[edit]The earliest so-called Venus figurines have been dated to the prehistoric Upper Paleolithic era (35–40 ka onwards).[29] Archaeological evidence from the islands of the Aegean Sea have yielded Neolithic era Cycladic figures from 4th and 3rd millennium BC, idols in namaste [which?] posture from Indus Valley civilization sites from the 3rd millennium BC, and much older petroglyphs around the world show humans began producing sophisticated images.[30][31] However, because of a lack of historic texts describing these, it is unclear what, if any connection with religious beliefs, these figures had,[32] or whether they had other meaning and uses, even as toys.[33][34][35]

The earliest historic records confirming idols are from the ancient Egyptian civilization, thereafter related to the Greek civilization.[36] By the 2nd millennium BC two broad forms of cult image appear, in one images are zoomorphic (god in the image of animal or animal-human fusion) and in another anthropomorphic (god in the image of man).[32] The former is more commonly found in ancient Egypt influenced beliefs, while the anthropomorphic images are more commonly found in Indo-European cultures.[36][37] Symbols of nature, useful animals or feared animals may also be included by both. The stelae from 4,000 to 2,500 BC period discovered in France, Ireland through Ukraine, and in Central Asia through South Asia, suggest that the ancient anthropomorphic figures included zoomorphic motifs.[37] In Nordic and Indian subcontinent, bovine (cow, ox, -*gwdus, -*g'ou) motifs or statues, for example, were common.[38][39] In Ireland, iconic images included pigs.[40]

The Ancient Egyptian religion was polytheistic, with large idols that were either animals or included animal parts. Ancient Greek civilization preferred human forms, with idealized proportions, for divine representation.[36] The Canaanites of West Asia incorporated a golden calf into their pantheon.[41]

The ancient philosophy and practices of the Greeks, thereafter Romans, were imbued with polytheistic idolatry.[42][43] They debate what is an image and if the use of image is appropriate. To Plato, images can be a remedy or poison to the human experience.[44] To Aristotle, states Paul Kugler, an image is an appropriate mental intermediary that "bridges between the inner world of the mind and the outer world of material reality", the image is a vehicle between sensation and reason. Idols are useful psychological catalysts, they reflect sense data and pre-existing inner feelings. They are neither the origins nor the destinations of thought but the intermediary in the human inner journey.[44][45] Fervid opposition to the idolatry of the Greeks and Romans was of Early Christianity and later Islam, as evidenced by the widespread desecration and defacement of ancient Greek and Roman sculptures that have survived into the modern era.[46][47][48]

Abrahamic religions

[edit]Judaism

[edit]

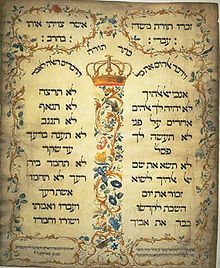

Judaism prohibits any form of idolatry[50] even if they are used to worship the one God of Judaism as occurred during the sin of the golden calf. According to the second word of the decalogue, Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image. The worship of foreign gods in any form or through icons is not allowed.[50][51]

Many Jewish scholars such as Rabbi Saadia Gaon, Rabbi Bahya ibn Paquda, and Rabbi Yehuda Halevi have elaborated on the issues of idolatry. One of the oft-cited discussions is the commentary of Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon (Maimonides) on idolatry.[51] According to the Maimonidean interpretation, idolatry in itself is not a fundamental sin, but the grave sin is the denial of God's omnipresence that occurs with the belief that God can be corporeal. In the Jewish belief, the only image of God is man, one who lives and thinks; God has no visible shape, and it is absurd to make or worship images; instead man must worship the invisible God alone.[51][52]

The commandments in the Hebrew Bible against idolatry forbade the practices and gods of ancient Akkad, Mesopotamia, and Egypt.[53][54] The Hebrew Bible states that God has no shape or form, is utterly incomparable, is everywhere and cannot be represented in a physical form of an idol.[55]

Biblical scholars have historically focused on the textual evidence to construct the history of idolatry in Judaism, a scholarship that post-modern scholars have increasingly begun deconstructing.[19] This biblical polemics, states Naomi Janowitz, a professor of Religious Studies, has distorted the reality of Israelite religious practices and the historic use of images in Judaism. The direct material evidence is more reliable, such as that from the archaeological sites, and this suggests that the Jewish religious practices have been far more complex than what biblical polemics suggest. Judaism included images and cultic statues in the First Temple period, the Second Temple period, Late Antiquity (2nd to 8th century CE), and thereafter.[19][56] Nonetheless, these sorts of evidence may be simply descriptive of Ancient Israelite practices in some—possibly deviant—circles, but cannot tell us anything about the mainstream religion of the Bible which proscribes idolatry.[57]

The history of Jewish religious practice has included idols and figurines made of ivory, terracotta, faience and seals.[19][58] As more material evidence emerged, one proposal has been that Judaism oscillated between idolatry and iconoclasm. However, the dating of the objects and texts suggest that the two theologies and liturgical practices existed simultaneously. The claimed rejection of idolatry because of monotheism found in Jewish literature and therefrom in biblical Christian literature, states Janowitz, has been unreal abstraction and flawed construction of the actual history.[19] The material evidence of images, statues and figurines taken together with the textual description of cherub and "wine standing for blood", for example, suggests that symbolism, making religious images, icon and index has been integral part of Judaism.[19][59][60] Every religion has some objects that represent the divine and stand for something in the mind of the faithful, and Judaism too has had its holy objects and symbols such as Torah scrolls and holy books, Tefillin, the Menorah, mezuzah and many more.[19]

Christianity

[edit]

Ideas on idolatry in Christianity are based on the first of Ten Commandments.

You shall have no other gods before me.[61]

This is expressed in the Bible in Exodus 20:3, Matthew 4:10, Luke 4:8 and elsewhere, e.g.:[61]

Ye shall make you no idols nor graven image, neither rear you up a standing image, neither shall ye set up any image of stone in your land, to bow down unto it: for I am the Lord your God. Ye shall keep my sabbaths, and reverence my sanctuary.

The Christian view of idolatry may generally be divided into two general categories: the Catholic and Eastern Orthodox view which accepts the use of religious images,[63] and the views of many Protestant churches that considerably restrict their use. However, many Protestants have used the image of the cross as a symbol.[64][65]

Catholicism

[edit]The Catholic Church and the Orthodox Church have traditionally defended the use of icons. The debate on what images signify and whether reverence with the help of icons in church is equivalent to idolatry has lasted for many centuries, particularly from the 7th century until the Reformation in the 16th century.[66] These debates have supported the inclusion of icons of Jesus Christ, the Virgin Mary, and the Apostles, the iconography expressed in stained glass, regional saints and other symbols of Christian faith. It has also supported the practices such as the Catholic mass, burning of candles before pictures, Christmas decorations and celebrations, and festive or memorial processions with statues of religious significance to Christianity.[66][67][68]

St. John of Damascus, in his "On the Divine Image", defended the use of icons and images, in direct response to the Byzantine iconoclasm that began widespread destruction of religious images in the 8th century, with support from emperor Leo III and continued by his successor Constantine V during a period of religious war with the invading Umayyads.[69] John of Damascus wrote, "I venture to draw an image of the invisible God, not as invisible, but as having become visible for our sakes through flesh and blood", adding that images are expressions "for remembrance either of wonder, or an honor, or dishonor, or good, or evil" and that a book is also a written image in another form.[70][71] He defended the religious use of images based on the Christian doctrine of Jesus as an incarnation.[72]

St. John the Evangelist cited John 1:14, stating that "the Word became flesh" indicates that the invisible God became visible, that God's glory manifested in God's one and only Son as Jesus Christ, and therefore God chose to make the invisible into a visible form, the spiritual incarnated into the material form.[73][74]

The early defense of images included exegesis of Old and New Testament. Evidence for the use of religious images is found in Early Christian art and documentary records. For example, the veneration of the tombs and statues of martyrs was common among early Christian communities. In 397 St. Augustine of Hippo, in his Confessions 6.2.2, tells the story of his mother making offerings for the tombs of martyrs and the oratories built in the memory of the saints.[75]

Images function as the Bible

for the illiterate, and

incite people to piety and virtue.

The Catholic defense mentions textual evidence of external acts of honor towards icons, arguing that there are a difference between adoration and veneration and that the veneration shown to icons differs entirely from the adoration of God. Citing the Old Testament, these arguments present examples of forms of "veneration" such as in Genesis 33:3, with the argument that "adoration is one thing, and that which is offered in order to venerate something of great excellence is another". These arguments assert, "the honor given to the image is transferred to its prototype", and that venerating an image of Christ does not terminate at the image itself – the material of the image is not the object of worship – rather it goes beyond the image, to the prototype.[77][76][78]

According to the Catechism of the Catholic Church:

The Christian veneration of images is not contrary to the first commandment which proscribes idols. Indeed, "the honor rendered to an image passes to its prototype," and "whoever venerates an image venerates the person portrayed in it." The honor paid to sacred images is a "respectful veneration," not the adoration due to God alone:

Religious worship is not directed to images in themselves, considered as mere things, but under their distinctive aspect as images leading us on to God incarnate. The movement toward the image does not terminate in it as image, but tends toward that whose image it is.[79]

It also points out the following:

Idolatry not only refers to false pagan worship. It remains a constant temptation to faith. Idolatry consists in divinizing what is not God. Man commits idolatry whenever he honors and reveres a creature in place of God, whether this be gods or demons (for example, satanism), power, pleasure, race, ancestors, the state, money, etc.[80]

The manufacture of images of Jesus, the Virgin Mary and Christian saints, along with prayers directed to these has been widespread among the Catholic faithful.[81]

Orthodox Church

[edit]The Eastern Orthodox Church has differentiated between latria and dulia. A latria is the worship due God, and latria to anyone or anything other than God is doctrinally forbidden by the Orthodox Church; however dulia has been defined as veneration of religious images, statues or icons which is not only allowed but obligatory.[82] This distinction was discussed by Thomas Aquinas in section 3.25 of Summa Theologiae.[83]

In Orthodox apologetic literature, the proper and improper use of images is extensively discussed. Exegetical Orthodox literature points to icons and the manufacture by Moses (under God's commandment) of the Bronze Snake in Numbers 21:9, which had the grace and power of God to heal those bitten by real snakes. Similarly, the Ark of the Covenant was cited as evidence of the ritual object above which Yahweh was present.[86][87]

Veneration of icons through proskynesis was codified in 787 AD by the Seventh Ecumenical Council.[88][89] This was triggered by the Byzantine Iconoclasm controversy that followed raging Christian-Muslim wars and a period of iconoclasm in West Asia.[88][90] The defense of images and the role of the Syrian scholar John of Damascus was pivotal during this period. The Eastern Orthodox Church has ever since celebrated the use of icons and images. Eastern Rite Catholics also accepts icons in their Divine Liturgy.[91]

Protestantism

[edit]The idolatry debate has been one of the defining differences between papal Catholicism and anti-papal Protestantism.[92] The anti-papal writers have prominently questioned the worship practices and images supported by Catholics, with many Protestant scholars listing it as the "one religious error larger than all others". The sub-list of erring practices have included among other things the veneration of Virgin Mary, the Catholic mass, the invocation of saints, and the reverence expected for and expressed to pope himself.[92] The charges of supposed idolatry against the Roman Catholics were leveled by a diverse group of Protestants, from Anglicans to Calvinists in Geneva.[92][93]

Protestants did not abandon all icons and symbols of Christianity. They typically avoid the use of images, except the cross, in any context suggestive of veneration. The cross remained their central icon.[64][65] Technically both major branches of Christianity have had their icons, states Carlos Eire, a professor of religious studies and history, but its meaning has been different to each and "one man's devotion was another man's idolatry".[94] This was particularly true not only in the intra-Christian debate, states Eire, but also when soldiers of Catholic kings replaced "horrible Aztec idols" in the American colonies with "beautiful crosses and images of Mary and the saints".[94]

Protestants often accuse Catholics of idolatry, iconolatry, and even paganism; in the Protestant Reformation such language was common to all Protestants. In some cases, such as the Puritan groups denounced all forms of religious objects, regardless of whether it was a statue or sculpture, or image, including the Christian cross.[95] The Waldensians were accused of idolatry by inquisitors.[96]

The body of Christ on the cross is an ancient symbol used within the Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, Anglican, and Lutheran Churches, in contrast with some Protestant groups, which use only a simple cross. In Judaism, the reverence to the icon of Christ in the form of cross has been seen as idolatry.[97] However, some Jewish scholars disagree and consider Christianity to be based on Jewish belief and not truly idolatrous.[98]

Islam

[edit]In Islamic sources, the concept of shirk (triliteral root: sh-r-k) can refer to "idolatry", though it is most widely used to denote "association of partners with God".[99] The concept of Kufr (k-f-r) can also include idolatry (among other forms of disbelief).[100][101] The one who practices shirk is called mushrik (plural mushrikun) in the Islamic scriptures.[102] The Quran forbids idolatry.[102] Over 500 mentions of kufr and shirk are found in the Quran,[100][103] and both concepts are strongly forbidden.[99]

The Islamic concept of idolatry extends beyond polytheism, and includes some Christians and Jews as muširkūn (idolaters) and kafirun (infidels).[104][105] For example:

Those who say, “Allah is the Messiah, son of Mary,” have certainly fallen into disbelief. The Messiah ˹himself˺ said, “O Children of Israel! Worship Allah—my Lord and your Lord.” Whoever associates others with Allah ˹in worship˺ will surely be forbidden Paradise by Allah. Their home will be the Fire. And the wrongdoers will have no helpers.

Shia classical theology differs in the concept of Shirk. According to Twelver theologians, the attributes and names of God have no independent and hypostatic existence apart from the being and essence of God. Any suggestion of these attributes and names being conceived of as separate is thought to entail polytheism. It would be even incorrect to say God knows by his knowledge which is in his essence but God knows by his knowledge which is his essence. Also God has no physical form and he is insensible.[106] The border between theoretical Tawhid and Shirk is to know that every reality and being in its essence, attributes and action are from him (from Him-ness), it is Tawhid. Every supernatural action of the prophets is by God's permission as Quran points to it. The border between the Tawhid and Shirk in practice is to assume something as an end in itself, independent from God, not as a road to God (to Him-ness).[107] Ismailis go deeper into the definition of Shirk, declaring they don't recognize any sort of ground of being by the esoteric potential to have intuitive knowledge of the human being. Hence, most Shias have no problem with religious symbols and artworks, and with reverence for Walis, Rasūls and Imams.

Islam strongly prohibits all form of idolatry, which is part of the sin of shirk (Arabic: شرك); širk comes from the Arabic root Š-R-K (ش ر ك), with the general meaning of "to share". In the context of the Qur'an, the particular sense of "sharing as an equal partner" is usually understood as "attributing a partner to Allah". Shirk is often translated as idolatry and polytheism.[99] In the Qur'an, shirk and the related word (plural Stem IV active participle) mušrikūn (مشركون) "those who commit shirk" refers to the enemies of Islam (as in verse 9.1–15).

Within Islam, shirk is sin that can only be forgiven if the person who commits it asks God for forgiveness; if the person who committed it dies without repenting God may forgive any sin except for committing shirk. [citation needed] In practice, especially among strict conservative interpretations of Islam, the term has been greatly extended and means deification of anyone or anything other than the singular God. [citation needed] In Salafi-Wahhabi interpretation, it may be used very widely to describe behaviour that does not literally constitute worship, including use of images of sentient beings, building a structure over a grave, associating partners with God, giving his characteristics to others beside him, or not believing in his characteristics.[citation needed] 19th century Wahhabis regarded idolatry punishable with the death penalty, a practice that was "hitherto unknown" in Islam.[108][109] However, Classical Orthodox Sunni thought used to be rich in Relics and Saint veneration, as well as pilgrimage to their shrines. Ibn Taymiyya, a medieval theologian that influenced modern days Salafists, was put in prison for his negation of veneration of relics and Saints, as well as pilgrimage to Shrines, which was considered unorthodox by his contemporary theologians.

According to Islamic tradition, over the millennia after Ishmael's death, his progeny and the local tribes who settled around the oasis of Zam-Zam gradually turned to polytheism and idolatry. Several idols were placed within the Kaaba representing deities of different aspects of nature and different tribes. Several heretical rituals were adopted in the Pilgrimage (Hajj) including doing naked circumambulation.[110]

In her book, Islam: A Short History, Karen Armstrong asserts that the Kaaba was officially dedicated to Hubal, a Nabatean deity, and contained 360 idols that probably represented the days of the year.[111] But by Muhammad's day, it seems that the Kaaba was venerated as the shrine of Allah, the High God. Allah was never represented by an idol.[112] Once a year, tribes from all around the Arabian peninsula, whether Christian or pagan, would converge on Mecca to perform the Hajj, marking the widespread conviction that Allah was the same deity worshipped by monotheists.[111] Guillaume in his translation of Ibn Ishaq, an early biographer of Muhammad, says the Ka'aba might have been itself addressed using a feminine grammatical form by the Quraysh.[113] Circumambulation was often performed naked by men and almost naked by women.[110] It is disputed whether al-Lat and Hubal were the same deity or different. Per a hypothesis by Uri Rubin and Christian Robin, Hubal was only venerated by Quraysh and the Kaaba was first dedicated to al-Lat, a supreme god of individuals belonging to different tribes, while the pantheon of the gods of Quraysh was installed in Kaaba after they conquered Mecca a century before Muhammad's time.[114]

Indian religions

[edit]Provenance

[edit]The first attested date in peer-reviewed academic literature for the worship of murti (Sanskrit) or vigraha (Sanskrit) in India is not clear, as different sources have different opinions and interpretations. However, the Indus Valley Civilization (circa 2500 - 1500 BCE) may have produced some of the earliest murtis or vigrahas in India, as evidenced by various terracotta and bronze figurines found in the archaeological sites. Some of these figurines have been interpreted as representations of deities, such as the so-called Pashupati seal, which depicts a horned figure surrounded by animals and possibly identified with Shiva. Another example is the bronze statuette of a Dancing Girl, which some scholars have associated with Parvati or Shakti. However, these interpretations are not universally accepted, and some scholars have argued that the Indus Valley Civilization did not practice murti or vigraha worship, but rather used symbols and signs to express their religious beliefs.[115]

The Vedic period (circa 1500 - 500 BCE) is traditionally considered as the origin of Hinduism proper, but it also did not emphasize murti or vigraha worship, as the Vedic religion was mainly focused on fire sacrifices and hymns to various gods and goddesses. However, some Vedic texts do mention the use of clay or wooden images for ritual purposes, such as the Shatapatha Brahmana (circa 8th - 6th century BCE), which describes how a clay image of Prajapati (the creator god) was made and consecrated for the agnicayana ritual. Another example, is the Aitareya Brahmana (circa 8th - 6th century BCE), which mentions how a wooden image of Varuna (the god of water and law) was installed in a temple and worshipped by the king. These examples suggest that murti or vigraha worship was not unknown in the Vedic period, but it was not widespread nor dominant.[115]

The post-Vedic period (circa 500 BCE - 300 CE) witnessed the emergence and development of various religious movements and schools, such as Buddhism, Jainism, Shaivism, Vaishnavism, Shaktism and others. This period also saw the rise of murti or vigraha worship as a prominent feature of Hinduism, as evidenced by various literary and archaeological sources. For instance, the Ramayana (circa 5th - 4th century BCE) and the Mahabharata (circa 4th - 3rd century BCE) contain several references to murti or vigraha worship, such as Rama worshipping a Shiva linga at Rameshwaram, or Krishna installing an image of Vishnu at Dwarka. Another example, is the Buddhist text Lalitavistara Sutra (circa 3rd century BCE - 3rd century CE), which mentions how Buddha's mother Maya dreamt of a white elephant entering her womb, and how King Suddhodana made an image of this elephant and worshipped it. Moreover, many stone and metal sculptures of various deities and saints have been found from this period onwards, such as the famous Pancha Rathas at Mahabalipuram (circa 7th century CE), which depict five chariots dedicated to different gods and goddesses.[115]

General

[edit]The oldest forms of the ancient religions of India apparently made no use of idols. While the Vedic literature leading up to Hinduism is extensive, in the form of Samhitas, Brahmanas, Aranyakas and Upanishads, and has been dated to have been composed over a period of centuries (1200 BC to 200 BC),[116] historical Vedic religion appears not to have used idols up to around 500 BC at least. The early Buddhist and Jain (pre-200 BC) traditions suggest no evidence of idolatry. The Vedic literature mentions many gods and goddesses, as well as the use of Homa (votive ritual using fire), but it does not mention images or their worship.[116][117] The ancient Buddhist, Hindu and Jaina texts discuss the nature of existence, whether there is or is not a creator deity such as in the Nasadiya Sukta of the Rigveda, they describe meditation, they recommend the pursuit of simple monastic life and self-knowledge, they debate the nature of absolute reality as Brahman or Śūnyatā, yet the ancient Indian texts mention no use of images. Indologists such as the Max Muller, Jan Gonda, Pandurang Vaman Kane, Ramchandra Narayan Dandekar, Horace Hayman Wilson, Stephanie Jamison and other scholars state that "there is no evidence for icons or images representing god(s)" in the ancient religions of India. Use of idols developed among the Indian religions later,[116][118] perhaps first in Buddhism, where large images of the Buddha appear by the 1st century AD.

According to John Grimes, a professor of Indian philosophy, Indian thought denied even dogmatic idolatry of its scriptures. Everything has been left to challenge, arguments and enquiry, with the medieval Indian scholar Vācaspati Miśra stating that not all scripture is authoritative, only scripture which "reveals the identity of the individual self and the supreme self as the non-dual Absolute".[119]

Buddhism

[edit]According to Eric Reinders, icons and idolatry have been an integral part of Buddhism throughout its later history.[120] Buddhists, from Korea to Vietnam, Thailand to Tibet, Central Asia to South Asia, have long produced temples and idols, altars and malas, relics to amulets, images to ritual implements.[120][121][122] The images or relics of Buddha are found in all Buddhist traditions, but they also feature gods and goddesses such as those in Tibetan Buddhism.[120][123]

Bhakti (called Bhatti in Pali) has been a common practice in Theravada Buddhism, where offerings and group prayers are made to Cetiya and particularly images of Buddha.[124][125] Karel Werner notes that Bhakti has been a significant practice in Theravada Buddhism, and states, "there can be no doubt that deep devotion or bhakti / bhatti does exist in Buddhism and that it had its beginnings in the earliest days".[126]

According to Peter Harvey – a professor of Buddhist Studies, Buddha idols and idolatry spread into northwest Indian subcontinent (now Pakistan and Afghanistan) and into Central Asia with Buddhist Silk Road merchants.[127] The Hindu rulers of different Indian dynasties patronized both Buddhism and Hinduism from 4th to 9th century, building Buddhist icons and cave temples such as the Ajanta Caves and Ellora Caves which featured Buddha idols.[128][129][130] From the 10th century, states Harvey, the raids into northwestern parts of South Asia by Muslim Turks destroyed Buddhist idols, given their religious dislike for idolatry. The iconoclasm was so linked to Buddhism, that the Islamic texts of this era in India called all idols as Budd.[127] The desecration of idols in cave temples continued through the 17th century, states Geri Malandra, from the offense of "the graphic, anthropomorphic imagery of Hindu and Buddhist shrines".[130][131]

In East Asia and Southeast Asia, worship in Buddhist temples with the aid of icons and sacred objects has been historic.[132] In Japanese Buddhism, for example, Butsugu (sacred objects) have been integral to the worship of the Buddha (kuyo), and such idolatry considered a part of the process of realizing one's Buddha nature. This process is more than meditation, it has traditionally included devotional rituals (butsudo) aided by the Buddhist clergy.[132] These practices are also found in Korea and China.[122][132]

Hinduism

[edit]In Hinduism, an icon, image or statue is called murti or pratima.[8][133] Major Hindu traditions such as Vaishnavism, Shaivism, Shaktism, and Smartism favor the use of a murti (idol). These traditions suggest that it is easier to dedicate time and focus on spirituality through anthropomorphic or non-anthropomorphic icons. The Bhagavad Gita – a Hindu scripture, in verse 12.5, states that only a few have the time and mind to ponder and fix on the unmanifested Absolute (abstract formless Brahman), and it is much easier to focus on qualities, virtues, aspects of a manifested representation of god, through one's senses, emotions and heart, because the way human beings naturally are.[134][135]

A murti in Hinduism, states Jeaneane Fowler – a professor of Religious Studies specializing on Indian Religions, is itself not god, it is an "image of god" and thus a symbol and representation.[8] A murti is a form and manifestation, states Fowler, of the formless Absolute.[8] Thus a literal translation of murti as idol is incorrect, when idol is understood as superstitious end in itself. Just like the photograph of a person is not the real person, a murti is an image in Hinduism but not the real thing, but in both cases the image reminds of something of emotional and real value to the viewer.[8] When a person worships a murti, it is assumed to be a manifestation of the essence or spirit of the deity, the worshipper's spiritual ideas and needs are meditated through it, yet the idea of ultimate reality – called Brahman in Hinduism – is not confined in it.[8]

Devotional (bhakti movement) practices centered on cultivating a deep and personal bond of love with God, often expressed and facilitated with one or more murti, and includes individual or community hymns, japa or singing (bhajan, kirtana, or arati). Acts of devotion, in major temples particularly, are structured on treating the murti as the manifestation of a revered guest,[11] and the daily routine can include awakening the murti in the morning and making sure that it "is washed, dressed, and garlanded."[136][137][Note 1]

In Vaishnavism, the building of a temple for the murti is considered an act of devotion, but non-murti symbolism is also common wherein the aromatic tulasi plant or shaligrama is an aniconic reminder of the spiritualism in Vishnu.[136] In the Shaivism tradition of Hinduism, Shiva may be represented as a masculine idol, or half-man half woman Ardhanarishvara form, in an anicon linga-yoni form. The worship rituals associated with the murti, correspond to ancient cultural practices for a beloved guest, and the murti is welcomed, taken care of, and then requested to retire.[138][139]

Christopher John Fuller states that an image in Hinduism cannot be equated with a deity and the object of worship is the divine whose power is inside the image, and the image is not the object of worship itself, Hindus believe everything is worthy of worship as it contains divine energy.[140] The idols are neither random nor intended as superstitious objects, rather they are designed with embedded symbolism and iconographic rules which sets the style, proportions, the colors, the nature of items the images carry, their mudra and the legends associated with the deity.[140][141][142] The Vāstusūtra Upaniṣad states that the aim of the murti art is to inspire a devotee towards contemplating the Ultimate Supreme Principle (Brahman).[142] This text adds (abridged):

From the contemplation of images grows delight, from delight faith, from faith steadfast devotion, through such devotion arises that higher understanding (parāvidyā) that is the royal road to moksha. Without the guidance of images, the mind of the devotee may go ashtray and form wrong imaginations. Images dispel false imaginations. (... ) It is in the mind of Rishis (sages), who see and have the power of discerning the essence of all created things of manifested forms. They see their different characters, the divine and the demoniac, the creative and the destructive forces, in their eternal interplay. It is this vision of Rishis, of gigantic drama of cosmic powers in eternal conflict, which the Sthapakas (Silpins, murti and temple artists) drew the subject-matter for their work.

— Pippalada, Vāstusūtra Upaniṣad, Introduction by Alice Boner et al.[143]

Some Hindu movements founded during the colonial era, such as the Arya Samaj and Satya Mahima Dharma reject idolatry.[144][145][146]

Jainism

[edit]

Devotional idolatry has been a prevalent ancient practice in various Jaina sects, wherein learned Tirthankara (Jina) and human gurus have been venerated with offerings, songs and Āratī prayers.[147] Like other major Indian religions, Jainism has premised its spiritual practices on the belief that "all knowledge is inevitably mediated by images" and human beings discover, learn and know what is to be known through "names, images and representations". Thus, idolatry has been a part of the major sects of Jainism such as Digambara and Shvetambara.[148] The earliest archaeological evidence of the idols and images in Jainism is from Mathura, and has been dated to be from the first half of the 1st millennium AD.[149]

The creation of idols, their consecration, the inclusion of Jaina layperson in idols and temples of Jainism by the Jaina monks has been a historic practice.[148] However, during the iconoclastic era of Islamic rule, between the 15th and 17th century, a Lonka sect of Jainism emerged that continued pursuing their traditional spirituality but without the Jaina arts, images and idols.[150]

Sikhism

[edit]Sikhism is a monotheistic Indian religion, and Sikh temples are devoid of idols and icons for God.[151][152] Yet, Sikhism strongly encourages devotion to God.[153][154] Some scholars call Sikhism a Bhakti sect of Indian traditions.[155][156]

In Sikhism, "Nirguni Bhakti" is emphasised – devotion to a divine without Gunas (qualities or form),[156][157][158] but its scripture also accepts representations of God with formless (nirguni) and with form (saguni), as stated in Adi Granth 287.[159][160] Sikhism condemns worshipping images or statues as if it were God,[161] but have historically challenged the iconoclastic policies and Hindu temple destruction activities of Islamic rulers in India.[162] Sikhs house their scripture and revere the Guru Granth Sahib as the final Guru of Sikhism.[163] It is installed in Sikh Gurdwara (temple), many Sikhs bow or prostrate before it on entering the gurdwara.[Note 1] Guru Granth Sahib is ritually installed every morning, and put to bed at night in many Gurdwaras.[170][171][172] In the Dasam Bani, Guru Gobind Singh wrote "I am idol-breaker" on line 95 of his Zafarnamah.[173]

Chinese and Sinosphere Traditions

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (August 2022) |

Japan

[edit]In Japan, there are images of some kami (i.e. deities) such as those of Fūjin and Raijin at the Buddhist temple Sanjūsangen-dō.

North Korean Juche

[edit]Kim Il Sung instituted worship of himself amongst the citizens of North Korea, and this act is considered the only instance of a modern country deifying its ruler.[174][175][176] As many citizens frequently bow before statues and portraits of him, scholars have considered the Juche state religion to be a form of idolatry.[177][178][179]

Traditional religions

[edit]Africa

[edit]Africa has numerous ethnic groups, and their diverse religious idea have been grouped as African Traditional Religions, sometimes abbreviated to ATR. These religions typically believe in a Supreme Being which goes by different regional names, as well as spirit world often linked to ancestors, and mystical magical powers through divination.[180] Idols and their worship have been associated with all three components in the African Traditional Religions.[181]

According to J.O. Awolalu, proselytizing Christians and Muslims have mislabelled idol to mean false god, when in the reality of most traditions of Africa, the object may be a piece of wood or iron or stone, yet it is "symbolic, an emblem and implies the spiritual idea which is worshipped".[182] The material objects may decay or get destroyed, the emblem may crumble or substituted, but the spiritual idea that it represents to the heart and mind of an African traditionalist remains unchanged.[182] Sylvester Johnson – a professor of African American and Religious Studies, concurs with Awolalu, and states that the colonial era missionaries who arrived in Africa, neither understood the regional languages nor the African theology, and interpreted the images and ritualism as "epitome of idolatry", projecting the iconoclastic controversies in Europe they grew up with, onto Africa.[183]

First with the arrival of Islam in Africa, then during the Christian colonial efforts, the religiously justified wars, the colonial portrayal of idolatry as proof of savagery, the destruction of idols and the seizure of idolaters as slaves marked a long period of religious intolerance, which supported religious violence and demeaning caricature of the African Traditional Religionists.[184][185][186] The violence against idolaters and idolatry of Traditional Religion practicers of Africa started in the medieval era and continued into the modern era.[187][188][189] The charge of idolatry by proselytizers, state Michael Wayne Cole and Rebecca Zorach, served to demonize and dehumanize local African populations, and justify their enslavement and abuse locally or far off plantations, settlements or for forced domestic labor.[190][191]

Americas

[edit]

Statues, images and temples have been a part of the Traditional Religions of the indigenous people of the Americas.[193][194][195] The Incan, Mayan and Aztec civilizations developed sophisticated religious practices that incorporated idols and religious arts.[195] The Inca culture, for example, has believed in Viracocha (also called Pachacutec) as the creator deity and nature deities such as Inti (sun deity), and Mama Cocha the goddess of the sea, lakes, rivers and waters.[196][197][198]

In Mayan culture, Kukulkan has been the supreme creator deity, also revered as the god of reincarnation, water, fertility and wind.[200] The Mayan people built step pyramid temples to honor Kukulkan, aligning them to the Sun's position on the spring equinox.[201] Other deities found at Mayan archaeological sites include Xib Chac – the benevolent male rain deity, and Ixchel – the benevolent female earth, weaving and pregnancy goddess.[201] A deity with aspects similar to Kulkulkan in the Aztec culture has been called Quetzalcoatl.[200]

Missionaries came to the Americas with the start of Spanish colonial era, and the Catholic Church did not tolerate any form of native idolatry, preferring that the icons and images of Jesus and Mary replace the native idols.[94][202][193] Aztec, for example, had a written history which included those about their Traditional Religion, but the Spanish colonialists destroyed this written history in their zeal to end what they considered as idolatry, and to convert the Aztecs to Catholicism. The Aztec Indians, however, preserved their religion and religious practices by burying their idols under the crosses, and then continuing their idol worship rituals and practices, aided by the syncretic composite of atrial crosses and their idols as before.[203]

During and after the imposition of Catholic Christianity during Spanish colonialism, the Incan people retained their original beliefs in deities through syncretism, where they overlay the Christian God and teachings over their original beliefs and practices.[204][205][206] The male deity Inti became accepted as the Christian God, but the Andean rituals centered around idolatry of Incan deities have been retained and continued thereafter into the modern era by the Incan people.[206][207]

Polynesia

[edit]The Polynesian people have had a range of polytheistic theologies found across the Pacific Ocean. The Polynesian people produced idols from wood, and congregated around these idols for worship.[208][209]

The Christian missionaries, particularly from the London Missionary Society such as John Williams, and others such as the Methodist Missionary Society, characterized these as idolatry, in the sense of islanders worshipping false gods. They sent back reports which primarily focussed on "overthrow of pagan idolatry" as evidence of their Christian sects triumph, with fewer mentions of actual converts and baptism.[210][211]

Religious tolerance and intolerance

[edit]The term false god is often used throughout the Abrahamic scriptures (Torah, Tanakh, Bible, and Quran) to single out Yahweh[212] (interpreted by Jews, Samaritans, and Christians) or Elohim/Allah[213] (interpreted by Muslims) as the only true God.[4] Nevertheless, the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament itself recognizes and reports that originally the Israelites were not monotheists but actively engaged in idolatry and worshipped many foreign, non-Jewish Gods besides Yahweh and/or instead of him,[214] such as Baal, Astarte, Asherah, Chemosh, Dagon, Moloch, Tammuz, and more, and continued to do so until their return from the Babylonian exile[212] (see Ancient Hebrew religion). Judaism, the oldest Abrahamic religion, eventually shifted into a strict, exclusive monotheism,[5] based on the sole veneration of Yahweh,[215][216][217] the predecessor to the Abrahamic conception of God.[Note 2]

The vast majority of religions in history have been and/or are still polytheistic, worshipping many diverse deities.[221] Moreover, the material depiction of a deity or more deities has always played an eminent role in all cultures of the world.[7] The claim to worship the "one and only true God" came to most of the world with the arrival of Abrahamic religions and is the distinguishing characteristic of their monotheistic worldview,[5][221][222][223] whereas virtually all the other religions in the world have been and/or are still animistic and polytheistic.[221] Some Neopagan religions such as Wicca utilize statues of deities within their worship experience.[224]

The accusations and presumption that all idols and images are devoid of symbolism, or that icons of one's own religion are "true, healthy, uplifting, beautiful symbolism, mark of devotion, divine", while of other person's religion are "false, an illness, superstitious, grotesque madness, evil addiction, satanic, and cause of all incivility" is more a matter of subjective personal interpretation, rather than objective impersonal truth.[19] Regina Schwartz and some other contemporary scholars state allegations that idols only represent false gods, followed by iconoclastic destruction is only little more than religious intolerance.[225][226] The Scottish Enlightenment philosopher David Hume wrote in his essay Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion (1779) that the worship of different gods and idols in Pagan religions is premised on religious pluralism, tolerance, and acceptance of diverse representations of the divine. In contrast, Abrahamic monotheistic religions are intolerant, have attempted to destroy freedom of expression and have violently forced others to accept and worship their conception of God.[20]

Gallery

[edit]-

The Ten Commandments on a monument on the grounds of the Texas State Capitol. The first commandment listed is interpreted as prohibiting idolatry, but the nature of the meaning of idolatry in the Biblical law in Christianity is disputed.

-

Bronze snake (formerly believed to be the one set up by Moses), in the main nave of Sant'Ambrogio basilica in Milan, Italy, a gift from Byzantine emperor Basil II (1007). It stands on an Ancient Roman granite pillar.

See also

[edit]- Buddhist devotion – prayer ritual in Buddhism

- Dambana

- Kemetism

- Deity

- El Tío

- Fetishism

- Jezebel

- Perceptions of religious imagery in natural phenomena

- Puja (Hinduism) – prayer ritual in Hinduism

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Such idol caring practices are found in other religions. For example, the Infant Jesus of Prague is venerated in many countries of the Catholic world. In the Prague Church it is housed, it is ritually cared for, cleaned and dressed by the sisters of the Carmelites Church, changing the Infant Jesus' clothing to one of the approximately hundred costumes donated by the faithfuls as gift of devotion.[164][165] The idol is worshipped with the faithful believing that it renders favors to those who pray to it.[165][166][167] Such ritualistic caring of the image of baby Jesus is found in other churches and homes in Central Europe and Portugal / Spain influenced Christian communities with different names, such as Menino Deus.[166][168][169]

- ^ Although the Semitic god El is indeed the most ancient predecessor to the Abrahamic god,[214][215][218][219] this specifically refers to the ancient ideas Yahweh once encompassed in the Ancient Hebrew religion, such as being a storm- and war-god, living on mountains, or controlling the weather.[214][215][218][219][220] Thus, in this page's context, "Yahweh" is used to refer to God as conceived in the Ancient Hebrew religion, and should not be referenced when describing his later worship in today's Abrahamic religions.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Moshe Halbertal; Avishai Margalit; Naomi Goldblum (1992). Idolatry. Harvard University Press. pp. 1–8, 85–86, 146–148. ISBN 978-0-674-44313-6.

- ^ DiBernardo, Sabatino (2008). "American Idol(atry): A Religious Profanation". The Journal of Religion and Popular Culture. 19 (1): 1–2. doi:10.3138/jrpc.19.1.001., Quote: "Idolatry (...) in the first commandment denotes the notion of worship, adoration, or reverence of an image of God."

- ^ Poorthuis, Marcel (2007). "6. Idolatry and the Mirror: Iconoclasm as a Prerequisite for Inter-Human Relations". Iconoclasm and Iconoclash, Chapter 6. Idolatry and the Mirror: Iconoclasm As A Prerequisite For Inter-Human Relations. BRILL Academic. pp. 125–140. doi:10.1163/ej.9789004161955.i-538.53. ISBN 9789004161955.

- ^ a b c d Angelini, Anna (2021). "Les dieux des autres: entre «démons» et «idoles»". L'imaginaire du démoniaque dans la Septante: Une analyse comparée de la notion de "démon" dans la Septante et dans la Bible Hébraïque. Supplements to the Journal for the Study of Judaism (in French). Vol. 197. Leiden and Boston: Brill Publishers. pp. 184–224. doi:10.1163/9789004468474_008. ISBN 978-90-04-46847-4.

- ^ a b c Leone, Massimo (Spring 2016). Asif, Agha (ed.). "Smashing Idols: A Paradoxical Semiotics" (PDF). Signs and Society. 4 (1). Chicago: University of Chicago Press on behalf of the Semiosis Research Center at Hankuk University of Foreign Studies: 30–56. doi:10.1086/684586. eISSN 2326-4497. hdl:2318/1561609. ISSN 2326-4489. S2CID 53408911. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 September 2017. Retrieved 28 July 2021.

- ^ Wendy Doniger (1999). Merriam-Webster's Encyclopedia of World Religions. Merriam-Webster. p. 497. ISBN 978-0-87779-044-0.

- ^ a b c d Frohn, Elke Sophie; Lützenkirchen, H.-Georg (2007). "Idol". In von Stuckrad, Kocku (ed.). The Brill Dictionary of Religion. Leiden and Boston: Brill Publishers. doi:10.1163/1872-5287_bdr_SIM_00041. ISBN 9789004124332. S2CID 240180055.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Jeaneane D. Fowler (1996), Hinduism: Beliefs and Practices, Sussex Academic Press, ISBN 978-1-898723-60-8, pages 41–45

- ^ a b Karel Werner (1995), Love Divine: Studies in Bhakti and Devotional Mysticism, Routledge, ISBN 978-0700702350, pages 45-46;

John Cort (2011), Jains in the World, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-979664-9, pages 80–85 - ^ Klaus Klostermaier (2010), A Survey of Hinduism, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0-7914-7082-4, pages 264–267

- ^ a b Lindsay Jones, ed. (2005). Gale Encyclopedia of Religion. Vol. 11. Thomson Gale. pp. 7493–7495. ISBN 978-0-02-865980-0.

- ^ Smart, Ninian (10 November 2020) [26 July 1999]. "Polytheism". Encyclopædia Britannica. Edinburgh: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Archived from the original on 11 November 2020. Retrieved 28 July 2021.

- ^ Aniconism, Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Marina Prusac; Kristine Kolrud (2014). Iconoclasm from Antiquity to Modernity. Ashgate. pp. 1–3. ISBN 978-1-4094-7033-5.

- ^ Willem J. van Asselt; Paul Van Geest; Daniela Muller (2007). Iconoclasm and Iconoclash: Struggle for Religious Identity. BRILL Academic. pp. 8–9, 52–60. ISBN 978-90-04-16195-5.

- ^ André Wink (1997). Al-Hind the Making of the Indo-Islamic World. BRILL Academic. pp. 317–324. ISBN 978-90-04-10236-1.

- ^ Barbara Roggema (2009). The Legend of Sergius Bahira: Eastern Christian Apologetics and Apocalyptic in Response to Islam. BRILL Academic. pp. 204–205. ISBN 978-90-04-16730-8.

- ^ Erich Kolig (2012). Conservative Islam: A Cultural Anthropology. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 71 with footnote 2. ISBN 978-0-7391-7424-1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Janowitz, Naomi (2007). "Good Jews Don't: Historical and Philosophical Constructions of Idolatry". History of Religions. 47 (2/3): 239–252. doi:10.1086/524212. S2CID 170216039.

- ^ a b Moshe Halbertal; Donniel Hartman (2007). Monotheism and Violence. Vol. Judaism and the Challenges of Modern Life. Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 105–112. ISBN 978-0-8264-9668-3.

- ^ John Bowker (2005). "Idolatry". The Concise Oxford Dictionary of World Religions. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780192800947.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-861053-3.

- ^ Douglas Harper (2015), Etymology Dictionary, Idolatry

- ^ Noah Webster (1841). An American Dictionary of the English Language. BL Hamlen. p. 857.

- ^ Stern, Sacha (1994). Jewish Identity in Early Rabbinic Writings. BRILL. p. 9 with footnotes 47–48. ISBN 978-9004100121. Retrieved 18 October 2013.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 14 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 288.

- ^ idolism, Merriam Webster;

Anthony Ephirim-Donkor (2012). African Religion Defined: A Systematic Study of Ancestor Worship among the Akan. University Press of America. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-7618-6058-7. - ^ iconolatry, Merriam Webster;

Elmar Waibl (1997). Dictionary of philosophical terms. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 42 see Bilderverehrung. ISBN 978-3-11-097454-6. - ^ John F. Thornton; Susan B. Varenne (2006). Steward of God's Covenant: Selected Writings. Random House. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-4000-9648-0.;

See John Calvin (1537) The Institutes of the Christian Religion, Quote: "The worship which they pay to their images they cloak with the name of εἰδωλοδυλεία (idolodulia), and deny to be εἰδωλολατρεία (idolatria). So they speak, holding that the worship which they call dulia may, without insult to God, be paid to statues and pictures. (...) For the Greek word λατρεύειν having no other meaning than to worship, what they say is just the same as if they were to confess that they worship their images without worshipping them. They cannot object that I am quibbling upon words. (...) But how eloquent soever they may be, they will never prove by their eloquence that one and the same thing makes two. Let them show how the things differ if they would be thought different from ancient idolaters." - ^ "The Cave Art Debate". Smithsonian Magazine. March 2012.

- ^ Richard G. Lesure (2011). Interpreting Ancient Figurines: Context, Comparison, and Prehistoric Art. Cambridge University Press. pp. 11–12. ISBN 978-1-139-49615-5.

- ^ National Museum, Seated Male in Namaskar pose, New Delhi, Government of India;

S Kalyanaraman (2007), Indus Script Cipher: Hieroglyphs of Indian Linguistic Area, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-0982897102, pages 234–236 - ^ a b Peter Roger Stuart Moorey (2003). Idols of the People: Miniature Images of Clay in the Ancient Near East. Oxford University Press. pp. 1–15. ISBN 978-0-19-726280-1.

- ^ S. Diamant (1974), A Prehistoric Figurine from Mycenae, The Annual of the British School at Athens, Vol. 69 (1974), pages 103–107

- ^ JÜRGEN THIMME (1965), DIE RELIGIÖSE BEDEUTUNG DER KYKLADENIDOLE, Antike Kunst, 8. Jahrg., H. 2. (1965), pages 72–86 (in German)

- ^ Colin Beckley; Elspeth Waters (2008). Who Holds the Moral High Ground?. Societas Imprint Academic. pp. 10–11. ISBN 978-1-84540-103-0.

- ^ a b c Barbara Johnson (2010). Moses and Multiculturalism. University of California Press. pp. 50–52. ISBN 978-0-520-26254-6.

- ^ a b Douglas Q. Adams (1997). Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture. Routledge. pp. 44, 125–133, 544–545. ISBN 978-1-884964-98-5.

- ^ Boria Sax (2001). The Mythical Zoo: An Encyclopedia of Animals in World Myth, Legend, and Literature. ABC-CLIO. pp. 48–49. ISBN 978-1-57607-612-5.

- ^ Douglas Q. Adams (1997). Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture. Routledge. pp. 124, 129–130, 134, 137–138. ISBN 978-1-884964-98-5.

- ^ James Bonwick (1894). Irish Druids and Old Irish Religions. Griffith, Farran. pp. 230–231.

- ^ Barbara Johnson (2010). Moses and Multiculturalism. University of California Press. pp. 21–22, 50–51. ISBN 978-0-520-26254-6.

- ^ Sylvia Estienne (2015). Rubina Raja and Jörg Rüpke (ed.). A Companion to the Archaeology of Religion in the Ancient World. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 379–384. ISBN 978-1-4443-5000-5.

- ^ Arthur P. Urbano (2013). The Philosophical Life. Catholic University of America Press. pp. 212–213 with footnotes 25–26. ISBN 978-0-8132-2162-5.

- ^ a b Paul Kugler (2008). Polly Young-Eisendrath; Terence Dawson (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Jung. Cambridge University Press. pp. 78–79. ISBN 978-1-139-82798-0.

- ^ Christopher Norris (1997). New Idols of the Cave: On the Limits of Anti-realism. Manchester University Press. pp. 106–110. ISBN 978-0-7190-5093-0.

- ^ David Sansone (2016). Ancient Greek Civilization. Wiley. pp. 275–276. ISBN 978-1-119-09814-0.

- ^ Sidney H. Griffith (2012). The Church in the Shadow of the Mosque: Christians and Muslims in the World of Islam. Princeton University Press. pp. 143–145. ISBN 978-1-4008-3402-0.

- ^ King, G. R. D. (1985). "Islam, iconoclasm, and the declaration of doctrine". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 48 (2): 267. doi:10.1017/s0041977x00033346. S2CID 162882785.

- ^ "UBA: Rosenthaliana 1768" [English: 1768: The Ten Commandments, copied in Amsterdam Jekuthiel Sofer] (in Dutch). Retrieved 26 April 2012.

- ^ a b Barry Kogan (1992). Proceedings of the Academy for Jewish Philosophy. University Press of America. pp. 169–170. ISBN 978-0-8191-7925-8.

- ^ a b c David Novak (1996). Leo Strauss and Judaism: Jerusalem and Athens Critically Revisited. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 72–73. ISBN 978-0-8476-8147-1.

- ^ Hava Tirosh-Samuelson; Aaron W. Hughes (2015). Arthur Green: Hasidism for Tomorrow. BRILL Academic. p. 231. ISBN 978-90-04-30842-8.

- ^ Shalom Goldman (2012). Wiles of Women/The Wiles of Men, The: Joseph and Potiphar's Wife in Ancient Near Eastern, Jewish, and Islamic Folklore. State University of New York Press. pp. 64–68. ISBN 978-1-4384-0431-8.

- ^ Abraham Joshua Heschel (2005). Heavenly Torah: As Refracted Through the Generations. Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 73–75. ISBN 978-0-8264-0802-0.

- ^ Frank L. Kidner; Maria Bucur; Ralph Mathisen; et al. (2007). Making Europe: People, Politics, and Culture, Volume I: To 1790. Cengage. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-618-00480-5.

- ^ Timothy Insoll (2002). Archaeology and World Religion. Routledge. pp. 112–113. ISBN 978-1-134-59798-7.

- ^ Reuven Chaim Klein (2018). God versus Gods: Judaism in the Age of Idolatry. Mosaica Press. ISBN 978-1946351463.

- ^ Allen Shapiro (2011), Judean pillar figurines: a study, MA Thesis, Advisor: Barry Gittlen, Towson University, United States

- ^ Rachel Neis (29 August 2013). The Sense of Sight in Rabbinic Culture. Cambridge University Press. pp. 99–100 with footnotes. ISBN 978-1-107-03251-4.

- ^ Kalman Bland (2001). Lawrence Fine (ed.). Judaism in Practice: From the Middle Ages Through the Early Modern Period. Princeton University Press. pp. 290–291. ISBN 978-0-691-05787-3.

- ^ a b T. J. Wray (2011). What the Bible Really Tells Us: The Essential Guide to Biblical Literacy. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. pp. 164–165. ISBN 978-1-4422-1293-0.

- ^ Terrance Shaw (2010). The Shaw's Revised King James Holy Bible. Trafford Publishing. p. 74. ISBN 978-1-4251-1667-5.

- ^ Frank K. Flinn (2007). Encyclopedia of Catholicism. Infobase. pp. 358–359. ISBN 978-0-8160-7565-2.

- ^ a b Leora Batnitzky (2009). Idolatry and Representation: The Philosophy of Franz Rosenzweig Reconsidered. Princeton University Press. pp. 147–156. ISBN 978-1-4008-2358-1.

- ^ a b Ryan K. Smith (2011). Gothic Arches, Latin Crosses: Anti-Catholicism and American Church Designs in the Nineteenth Century. University of North Carolina Press. pp. 79–81. ISBN 978-0-8078-7728-9.

- ^ a b Moshe Halbertal; Avishai Margalit; Naomi Goldblum (1992). Idolatry. Harvard University Press. pp. 39–40, 102–103, 116–119. ISBN 978-0-674-44313-6.

- ^ L. A. Craighen (1914). The Practice of Idolatry. Taylor & Taylor. pp. 21–26, 30–31.

- ^ William L. Vance (1989). America's Rome: Catholic and contemporary Rome. Yale University Press. pp. 5–8, 12, 17–18. ISBN 978-0-300-04453-9.

- ^ Stephen Gero (1973). Byzantine Iconoclasm During the Reign of Leo III: With Particular Attention to the Oriental Sources. Corpus scriptorum Christianorum Orientalium: Subsidia. pp. 1–7, 44–45. ISBN 9789042903876.

- ^ Saint John (of Damascus) (1898). St. John Damascene on Holy Images: (pros Tous Diaballontas Tas Agias Eikonas). T. Baker. pp. 5–6, 12–17.

- ^ Hans J. Hillerbrand (2012). A New History of Christianity. Abingdon. pp. 131–133, 367. ISBN 978-1-4267-1914-1.

- ^ Benedict Groschel (2010). I Am with You Always: A Study of the History and Meaning of Personal Devotion to Jesus Christ for Catholic, Orthodox, and Protestant Christians. Ignatius. pp. 58–60. ISBN 978-1-58617-257-2.

- ^ Jeffrey F. Hamburger (2002). St. John the Divine: The Deified Evangelist in Medieval Art and Theology. University of California Press. pp. 3, 18–24, 30–31. ISBN 978-0-520-22877-1.

- ^ Ronald P. Byars (2002). The Future of Protestant Worship: Beyond the Worship Wars. Westminster John Knox Press. pp. 43–44. ISBN 978-0-664-22572-8.

- ^ Kenelm Henry Digby (1841). Mores Catholici : Or Ages of Faith. Catholic Society. pp. 408–410.

- ^ a b Natasha T. Seaman; Hendrik Terbrugghen (2012). The Religious Paintings of Hendrick Ter Brugghen: Reinventing Christian Painting After the Reformation in Utrecht. Ashgate. pp. 23–29. ISBN 978-1-4094-3495-5.

- ^ Horst Woldemar Janson; Anthony F. Janson (2003). History of Art: The Western Tradition. Prentice Hall. p. 386. ISBN 978-0-13-182895-7.

- ^ Henry Ede Eze (2011). Images in Catholicism ...idolatry?: Discourse on the First Commandment With Biblical Citations. St. Paul Press. pp. 11–14. ISBN 978-0-9827966-9-6.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church - Paragraph # 2132. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ^ Catechism of The Catholic Church, passage 2113, p. 460, Geoffrey Chapman, 1999

- ^ Thomas W. L. Jones (1898). The Queen of Heaven: Màmma Schiavona (the Black Mother), the Madonna of the Pignasecea: a Delineation of the Great Idolatry. pp. 1–2.

- ^ Kathleen M. Ashley; Robert L. A. Clark (2001). Medieval Conduct. University of Minnesota Press. pp. 211–212. ISBN 978-0-8166-3576-4.

- ^ Bernard Lonergan (2016). The Incarnate Word: The Collected Works of Bernard Lonergan, Volume 8. University of Toronto Press. pp. 310–314. ISBN 978-1-4426-3111-3.

- ^ Rev. Robert William Dibdin (1851). England warned and counselled; 4 lectures on popery and tractarianism. James Nisbet. p. 20.

- ^ Gary Waller (2013). Walsingham and the English Imagination. Ashgate. p. 153. ISBN 978-1-4094-7860-7.

- ^ Sebastian Dabovich (1898). The Holy Orthodox Church: Or, The Ritual, Services and Sacraments of the Eastern Apostolic (Greek-Russian) Church. American Review of Eastern Orthodoxy. pp. 21–22. ISBN 9780899810300.

- ^ Ulrich Broich; Theo Stemmler; Gerd Stratmann (1984). Functions of Literature. Niemeyer. pp. 120–121. ISBN 978-3-484-40106-8.

- ^ a b Ambrosios Giakalis (2005). Images of the Divine: The Theology of Icons at the Seventh Ecumenical Council. Brill Academic. pp. viii–ix, 1–3. ISBN 978-90-04-14328-9.

- ^ Gabriel Balima (2008). Satanic Christianity and the Creation of the Seventh Day. Dorrance. pp. 72–73. ISBN 978-1-4349-9280-2.

- ^ Patricia Crone (1980), Islam, Judeo-Christianity and Byzantine Iconoclasm, Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam, Volume 2, pages 59–95

- ^ James Leslie Houlden (2003). Jesus in History, Thought, and Culture: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 369–370. ISBN 978-1-57607-856-3.

- ^ a b c Anthony Milton (2002). Catholic and Reformed: The Roman and Protestant Churches in English Protestant Thought. Cambridge University Press. pp. 186–195. ISBN 978-0-521-89329-9.

- ^ James Noyes (2013). The Politics of Iconoclasm: Religion, Violence and the Culture of Image-Breaking in Christianity and Islam. Tauris. pp. 31–37. ISBN 978-0-85772-288-1.

- ^ a b c Carlos M. N. Eire (1989). War Against the Idols: The Reformation of Worship from Erasmus to Calvin. Cambridge University Press. pp. 5–7. ISBN 978-0-521-37984-7.

- ^ Richardson, R. C. (1972). Puritanism in north-west England: a regional study of the diocese of Chester to 1642. Manchester, England: Manchester University Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-7190-0477-3.

- ^ Mankey, J. (2022). The Witches' Sabbath: An Exploration of History, Folklore & Modern Practice. Llewellyn Worldwide, Limited. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-7387-6717-8. Retrieved 14 March 2023.

- ^ Leora Faye Batnitzky (2000). Idolatry and Representation: The Philosophy of Franz Rosenzweig Reconsidered. Princeton University Press. p. 145. ISBN 978-0-691-04850-5.

- ^ Steinsaltz, Rabbi Adin. "Introduction - Masechet Avodah Zarah". The Coming Week's Daf Yomi. Retrieved 31 May 2013., Quote: "Over time, however, new religions developed whose basis is in Jewish belief – such as Christianity and Islam – which are based on belief in the Creator and whose adherents follow commandments that are similar to some Torah laws (see the uncensored Rambam in his Mishneh Torah, Hilkhot Melakhim 11:4). All of the rishonim agree that adherents of these religions are not idol worshippers and should not be treated as the pagans described in the Torah."

- ^ a b c Shirk, Encyclopædia Britannica, Quote: "Shirk, (Arabic: "making a partner [of someone]"), in Islam, idolatry, polytheism, and the association of God with other deities. The definition of Shirk differs in Islamic Schools, from Shiism and some classical Sunni Sufism accepting, sometimes, images, pilgrimage to shrines and veneration of relics and saints, to the more puritan Salafi-Wahhabi current, that condemns all the previous mentioned practices. The Quran stresses in many verses that God does not share his powers with any partner (sharik). It warns those who believe their idols will intercede for them that they, together with the idols, will become fuel for hellfire on the Day of Judgment (21:98)."

- ^ a b Waldman, Marilyn Robinson (1968). "The Development of the Concept of Kufr in the Qur'ān". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 88 (3): 442–455. doi:10.2307/596869. JSTOR 596869.

- ^ Juan Eduardo Campo (2009). Encyclopedia of Islam. Infobase. pp. 420–421. ISBN 978-1-4381-2696-8., Quote: "[Kafir] They included those who practiced idolatry, did not accept the absolute oneness of God, denied that Muhammad was a prophet, ignored God's commandments and signs (singular aya) and rejected belief in a resurrection and final judgment."

- ^ a b G. R. Hawting (1999). The Idea of Idolatry and the Emergence of Islam: From Polemic to History. Cambridge University Press. pp. 47–51, 67–70. ISBN 978-1-139-42635-0.

- ^ Reuven Firestone (1999). Jihad: The Origin of Holy War in Islam. Oxford University Press. pp. 88–89. ISBN 978-0-19-535219-1.

- ^ Hugh Goddard (2000). A History of Christian-Muslim Relations. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 28. ISBN 978-1-56663-340-6., Quote: "in some verses it does appear to be suggested that Christians are guilty of both kufr and shirk. This is particularly the case in 5:72 ... In addition to 9:29, therefore, which has been discussed above and which refers to both Jews and Christians, other verses are extremely hostile to both Jews and Christians, other verses are extremely hostile to Christians in particular, suggesting that they both disbelieve (kafara) and are guilty of shirk."

- ^ Oliver Leaman (2006). The Qur'an: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 144–146. ISBN 978-0-415-32639-1.

- ^ Momen (1985), p. 176

- ^ Motahari, Morteza (1985). Fundamentals of Islamic thought: God, man, and the universe. Mizan Press. OCLC 909092922.

- ^ Simon Ross Valentine (2014). Force and Fanaticism: Wahhabism in Saudi Arabia and Beyond. Oxford University Press. pp. 47–48. ISBN 978-1-84904-464-6., Quote: "In reference to Wahhabi strictness in applying their moral code, Corancez writes that the distinguishing feature of the Wahhabis was their intolerance, which they pursued to hitherto unknown extremes, holding idolatry as a crime punishable by death".

- ^ G. R. Hawting (1999). The Idea of Idolatry and the Emergence of Islam: From Polemic to History. Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–6, 80–86. ISBN 978-1-139-42635-0.

- ^ a b Ibn Ishaq, Muhammad (1955). Ibn Ishaq's Sirat Rasul Allah – The Life of Muhammad Translated by A. Guillaume. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 88–9. ISBN 9780196360331.

- ^ a b Karen Armstrong (2002). Islam: A Short History. Random House Publishing. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-8129-6618-3.

- ^ "Allah – Oxford Islamic Studies Online". www.oxfordislamicstudies.com. Archived from the original on 19 December 2015. Retrieved 25 August 2018.

Only god in Mecca not represented by idol.

- ^ Ibn Ishaq, Muhammad (1955). Ibn Ishaq's Sirat Rasul Allah – The Life of Muhammad Translated by A. Guillaume. The text reads "O God, do not be afraid", the second footnote reads "The feminine form indicates the Ka'ba itself is addressed". Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 85 footnote 2. ISBN 9780196360331.

- ^ Christian Julien Robin (2012). Arabia and Ethiopia. In The Oxford Handbook of Late Antiquity. OUP USA. pp. 304–305. ISBN 9780195336931.

- ^ a b c Source: https://www.oneindia.com/india/why-india-is-a-land-of-murti-and-vigraha-and-not-idols-and-idolators-as-perceived-by-the-west-3455405.html (accessed: Wednesday September 27, 2023)

- ^ a b c Noel Salmond (2006). Hindu Iconoclasts: Rammohun Roy, Dayananda Sarasvati, and Nineteenth-Century Polemics against Idolatry. Wilfrid Laurier University Press. pp. 15–17. ISBN 978-1-55458-128-3.

- ^ Richard Payne (2015). Michael Witzel (ed.). Homa Variations: The Study of Ritual Change Across the Longue Durée. Oxford University Press. pp. 1–5, 143–148. ISBN 978-0-19-935158-9.; Phyllis Granoff (2000), Other people's rituals: Ritual Eclecticism in early medieval Indian religious, Journal of Indian Philosophy, Volume 28, Issue 4, pages 399–424

- ^ Stephanie W. Jamison (2011), The Ravenous Hyenas and the Wounded Sun: Myth and Ritual in Ancient India, Cornell University Press, ISBN 978-0801477324, pages 15-17

- ^ John Grimes (1994). Problems and Perspectives in Religious Discourse. State University of New York Press. pp. 60–61. ISBN 978-0-7914-1791-1.

- ^ a b c Eric Reinders (2005). Francesco Pellizzi (ed.). Anthropology and Aesthetics, Volume 48: Autumn 2005. Harvard University Press. pp. 61–63. ISBN 978-0-87365-766-2.

- ^ Minoru Kiyota (1985), Tathāgatagarbha Thought: A Basis of Buddhist Devotionalism in East Asia, Japanese Journal of Religious Studies, Vol. 12, No. 2/3, pages 207–231

- ^ a b Pori Park (2012), Devotionalism Reclaimed: Re-mapping Sacred Geography in Contemporary Korean Buddhism, Journal of Korean Religions, Vol. 3, No. 2, pages 153–171

- ^ Allan Andrews (1993), Lay and Monastic Forms of Pure Land Devotionalism: Typology and History, Numen, Vol. 40, No. 1, pages 16–37

- ^ Donald Swearer (2003), Buddhism in the Modern World: Adaptations of an Ancient Tradition (Editors: Heine and Prebish), Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195146981, pages 9–25

- ^ Karen Pechelis (2011), The Bloomsbury Companion to Hindu Studies (Editor: Jessica Frazier), Bloomsbury, ISBN 978-1472511515, pages 109–112

- ^ Karel Werner (1995), Love Divine: Studies in Bhakti and Devotional Mysticism, Routledge, ISBN 978-0700702350, pages 45–46

- ^ a b Peter Harvey (2013). An Introduction to Buddhism: Teachings, History and Practices. Cambridge University Press. pp. 194–195. ISBN 978-0-521-85942-4.

- ^ Richard Cohen (2006). Beyond Enlightenment: Buddhism, Religion, Modernity. Routledge. pp. 83–84. ISBN 978-1-134-19205-2., Quote: Hans Bakker's political history of the Vakataka dynasty observed that Ajanta caves belong to the Buddhist, not the Hindu tradition. That this should be so is already remarkable in itself. By all we know of Harisena he was a Hindu; (...).

- ^ Spink, Walter M. (2006). Ajanta: History and Development Volume 5: Cave by Cave. Leiden: Brill Academic. pp. 179–180. ISBN 978-90-04-15644-9.

- ^ a b Geri Hockfield Malandra (1993). Unfolding A Mandala: The Buddhist Cave Temples at Ellora. State University of New York Press. pp. 1–4. ISBN 978-0-7914-1355-5.

- ^ Trudy Ring; Noelle Watson; Paul Schellinger (2012). Asia and Oceania: International Dictionary of Historic Places. Routledge. p. 256. ISBN 978-1-136-63979-1., Quote: "Some had been desecrated by zealous Muslims during their occupation of Maharashtra in the fifteenth, sixteenth and seventeenth centuries."

- ^ a b c Fabio Rambelli; Eric Reinders (2012). Buddhism and Iconoclasm in East Asia: A History. Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 17–19, 23–24, 89–93. ISBN 978-1-4411-8168-8.

- ^ "pratima (Hinduism)". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 21 August 2011.

- ^ Brant Cortright (2010). Integral Psychology: Yoga, Growth, and Opening the Heart. State University of New York Press. pp. 106–107. ISBN 978-0-7914-8013-7.

- ^ "Bhagavad-Gita: Chapter 12, Verse 5".

- ^ a b Klaus Klostermaier (2007) Hinduism: A Beginner's Guide, 2nd Edition, Oxford: OneWorld Publications, ISBN 978-1-85168-163-1, pages 63–65

- ^ Fuller, C. J. (2004), The Camphor Flame: Popular Hinduism and Society in India, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, pp. 67–68, ISBN 978-0-691-12048-5

- ^ Michael Willis (2009), The Archaeology of Hindu Ritual, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-51874-1, pages 96–112, 123–143, 168–172

- ^ Paul Thieme (1984), "Indische Wörter und Sitten," in Kleine Schriften (Wiesbaden), Vol. 2, pages 343–370

- ^ a b Christopher John Fuller (2004). The Camphor Flame: Popular Hinduism and Society in India. Princeton University Press. pp. 58–61. ISBN 978-0-691-12048-5.

- ^ PK Acharya, A summary of the Mānsāra, a treatise on architecture and cognate subjects, PhD Thesis awarded by Rijksuniversiteit te Leiden, published by BRILL, OCLC 898773783, pages 49–56, 63–65

- ^ a b Alice Boner, Sadāśiva Rath Śarmā and Bettina Bäumer (2000), Vāstusūtra Upaniṣad, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-0090-8, pages 7–9, for context see 1–10

- ^ Alice Boner, Sadāśiva Rath Śarmā and Bettina Bäumer (2000), Vāstusūtra Upaniṣad, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-0090-8, page 9

- ^ Naidoo, Thillayvel (1982). The Arya Samaj Movement in South Africa. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 158. ISBN 978-81-208-0769-3.

- ^ Lata, Prem (1990). Swami Dayānanda Sarasvatī. Sumit Publications. p. x. ISBN 978-81-7000-114-0.

- ^ Bhagirathi Nepak. Mahima Dharma, Bhima Bhoi and Biswanathbaba Archived 10 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ John Cort, Jains in the World : Religious Values and Ideology in India, Oxford University Press, ISBN, pages 64–68, 86–90, 100–112

- ^ a b John Cort (2010). Framing the Jina: Narratives of Icons and Idols in Jain History. Oxford University Press. pp. 3, 8–12, 45–46, 219–228, 234–236. ISBN 978-0-19-045257-5.

- ^ Paul Dundas (2002). The Jains, 2nd Edition. Routledge. pp. 39–40, 48–53. ISBN 978-0-415-26606-2.

- ^ Suresh K. Sharma; Usha Sharma (2004). Cultural and Religious Heritage of India: Jainism. Mittal. pp. 53–54. ISBN 978-81-7099-957-7.

- ^ W. Owen Cole; Piara Singh Sambhi (1993). Sikhism and Christianity: A Comparative Study (Themes in Comparative Religion). Wallingford, United Kingdom: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 117–118. ISBN 978-0333541074.

- ^ Mark Juergensmeyer, Gurinder Singh Mann (2006). The Oxford Handbook of Global Religions. US: Oxford University Press. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-19-513798-9.

- ^ S Deol (1998), Japji: The Path of Devotional Meditation, ISBN 978-0-9661027-0-3, page 11

- ^ HS Singha (2009), The Encyclopedia of Sikhism, Hemkunt Press, ISBN 978-81-7010-301-1, page 110

- ^ W. Owen Cole and Piara Singh Sambhi (1997), A Popular Dictionary of Sikhism: Sikh Religion and Philosophy, Routledge, ISBN 978-0700710485, page 22

- ^ a b David Lorenzen (1995), Bhakti Religion in North India: Community Identity and Political Action, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0791420256, pages 1–3

- ^ Hardip Syan (2014), in The Oxford Handbook of Sikh Studies (Editors: Pashaura Singh, Louis E. Fenech), Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0199699308, page 178

- ^ A Mandair (2011), Time and religion-making in modern Sikhism, in Time, History and the Religious Imaginary in South Asia (Editor: Anne Murphy), Routledge, ISBN 978-0415595971, page 188-190

- ^ Mahinder Gulati (2008), Comparative Religious And Philosophies : Anthropomorphism And Divinity, Atlantic, ISBN 978-8126909025, page 305

- ^ W.O. Cole; Piara Singh Sambhi (2016). Sikhism and Christianity: A Comparative Study. Springer. pp. 34–35. ISBN 978-1-349-23049-5.

- ^ W.O. Cole; Piara Singh Sambhi (2016). Sikhism and Christianity: A Comparative Study. Springer. pp. 36–37. ISBN 978-1-349-23049-5.

- ^ John F. Richards (1995). The Mughal Empire. Cambridge University Press. p. 178. ISBN 978-0-521-56603-2.

- ^ Jane Bingham (2007), Sikhism, Atlas of World Faiths, ISBN 978-1599200590, pages 19-20