Immigration to New Zealand

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2022) |

Migration to New Zealand began only very recently in human history, with Polynesian settlement in New Zealand, previously uninhabited, about 1250 CE to 1280 CE. European migration provided a major influx, especially following the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840. Subsequent immigrants have come chiefly from the British Isles, but also from continental Europe, the Pacific, the Americas and Asia.

Given the isolation of the archipelago, people generally do not come to New Zealand casually: one cannot wander across a border or gradually encroach on neighbouring land in order to reach remote South Pacific islands. Settlement usually takes place deliberately, with waves of people transported from afar by successive boats or aeroplanes, and often landing in specific locales (rohe, colonies and provinces). This process results in relatively distinct groups of residents; nevertheless, repeated attempts have taken place to declare, define or meld such groups as a single common people or nation.

Polynesian settlement

[edit]Polynesians in the South Pacific were the first to discover the landmass of New Zealand. Eastern Polynesian explorers had settled in New Zealand by approximately the thirteenth century CE with most evidence pointing to an arrival date of about 1280. Their arrival gave rise to the Māori culture and the Māori language, both unique to New Zealand, although very closely related to analogues in other parts of Eastern Polynesia. Evidence from Wairau Bar and the Chatham Islands shows that the Polynesian colonists maintained many parts of their east Polynesian culture such as burial customs for at least 50 years. Especially strong resemblances link Māori to the languages and cultures of the Cook and Society Islands, which are regarded as the most likely places of origin.[1] Moriori settled the Chatham Islands during the 15th century from mainland New Zealand.

European settlement

[edit]Due to New Zealand's geographic isolation, several centuries passed before the next phase of settlement, that of Europeans. Only then did the original inhabitants need to distinguish themselves from the new arrivals, using the adjective "māori" which means "ordinary" or "indigenous" which later became a noun although the term New Zealand native was common until about 1890. Māori thought of their tribe (iwi) as a nation.[citation needed]

James Cook claimed New Zealand for Britain on his arrival in 1769. The establishment of British colonies in Australia from 1788 and the boom in whaling and sealing in the Southern Ocean brought many Europeans to the vicinity of New Zealand, with some settling. Whalers and sealers were often itinerant and the first real settlers were missionaries and traders in the Bay of Islands area from 1809. By 1830 there was a population of about 800 non-Māori, which included about 200 runaway convicts and seamen who often married into the Māori community.[citation needed] The seamen often lived in New Zealand for a short time before joining another ship a few months later. In 1839 there were 1100 Europeans living in the North Island. Regular outbreaks of extreme violence, mainly between Māori hapu, known as the Musket Wars, resulted in the deaths of between 20,000 and 50,000 Māori up until 1843.[citation needed] Violence against European shipping, cannibalism and the lack of established law and order made settling in New Zealand a risky prospect. By the late 1830s many Māori were nominally Christian and had freed many of the Māori slaves that had been captured during the Musket Wars. By this time, many Māori, especially in the north, could read and write Māori and, to a lesser extent, English.

Migration from 1840

[edit]

European migration has resulted in a deep legacy being left on the social and political structures of New Zealand. Early visitors to New Zealand included whalers, sealers, missionaries, mariners, and merchants, attracted to natural resources in abundance.

New Zealand was administered from New South Wales from 1788[dubious – discuss] and the first permanent settlers were Australians. Some were escaped convicts, and others were ex-convicts that had completed their sentences. Smaller numbers came directly from Great Britain, Ireland, Germany (forming the next biggest immigrant group after the British and Irish),[2] France, Portugal, the Netherlands, Denmark, The United States, and Canada.

In 1840 representatives of the British Crown signed the Treaty of Waitangi with 240 Māori chiefs throughout New Zealand, motivated by plans for a French colony at Akaroa and land purchases by the New Zealand Company in 1839. British sovereignty was then proclaimed over New Zealand in May 1840 and by 1841 New Zealand had ceased being an Australian colony.

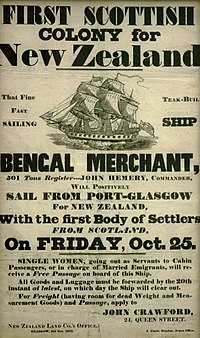

Following the formalising of sovereignty, organised and structured flow of migrants from Great Britain and Ireland began. Government-chartered ships like the clipper Gananoque and the Glentanner carried immigrants to New Zealand. Typically clipper ships left British ports such as London and travelled south through the central Atlantic to about 43 degrees south to pick up the strong westerly winds that carried the clippers well south of South Africa and Australia. Ships would then head north once in the vicinity of New Zealand. The Glentanner migrant ship of 610 tonnes made two runs to New Zealand and several to Australia carrying 400 tonne of passengers and cargo. Travel time was about 3 to 3+1⁄2 months to New Zealand. Cargo carried on the Glentanner for New Zealand included coal, slate, lead sheet, wine, beer, cart components, salt, soap and passengers' personal goods. On the 1857 passage the ship carried 163 official passengers, most of them government assisted. On the return trip the ship carried a wool cargo worth 45,000 pounds.[3] In the 1860s discovery of gold started a gold rush in Otago. By 1860 more than 100,000 British and Irish settlers lived throughout New Zealand. The Otago Association actively recruited settlers from Scotland, creating a definite Scottish influence in that region, while the Canterbury Association recruited settlers from the south of England, creating a definite English influence over that region.[4]

In the 1860s most migrants settled in the South Island due to gold discoveries and the availability of flat grass covered land for pastoral farming. The low number of Māori (about 2,000) and the absence of warfare gave the South Island many advantages. It was only when the New Zealand wars ended that the North Island again became an attractive destination. In order to attract settlers to the North Island the Government and Auckland Provisional government initiated the Waikato Immigration Scheme which ran from 1864 and 1865.[5][6] The central government originally intended to bring about 20,000 immigrants to the Waikato from the British Isles and the Cape Colony in South Africa to consolidate the government position after the wars and develop the Waikato area for European settlement. The immigration scheme settlers were allocated quarter-acre town sections and ten-acre rural sections. They were required to work on and improve the sections for two years after which a Crown Grant would be issued, giving them ownership.[7] In all, 13 ships travelled to New Zealand under the scheme, arriving from London, Glasgow and Cape Town.[8]

In the 1870s, Premier Julius Vogel borrowed millions of pounds from Britain to help fund capital development such as a nationwide rail system, lighthouses, ports and bridges, and encouraged mass migration from Britain. By 1870 the non-Māori population reached over 250,000.[9]

Other smaller groups of settlers came from Germany, Scandinavia, and other parts of Europe as well as from China and India, but English, Scottish and Irish settlers made up the vast majority, and did so for the next 150 years. Today, the majority of New Zealanders have some sort of English, Scottish, Welsh and Irish ancestry. This comes with last names (mainly English, Irish, and Scottish) as well.

Between 1881 and the 1920s, the New Zealand Parliament passed legislation that intended to limit Asiatic migration to New Zealand, and prevented Asians from naturalising.[10] In particular, the New Zealand government levied a poll tax on Chinese immigrants up until the 1930s. New Zealand finally abolished the poll tax in 1944. Large numbers of Dalmatians fled from the Austro-Hungarian empire to settle in New Zealand around 1900. They settled mainly in West Auckland and often worked to establish vineyards and orchards or worked on gum fields in Northland.

An influx of Jewish refugees from central Europe came in the 1930s.

Many of the persons of Polish descent in New Zealand arrived as orphans via Siberia and Iran during World War II.

Post World War II migration

[edit]With the various agencies of the United Nations dealing with humanitarian efforts following World War II, New Zealand accepted about 5,000 refugees and displaced persons from Europe, and more than 1,100 Hungarians between 1956 and 1959 (see Refugees in New Zealand). The post-WWII immigration included more people from Greece, Italy, Poland and the former Yugoslavia.

New Zealand limited immigration to those who would meet a labour shortage in New Zealand. To encourage those to come, the government introduced free and assisted passages in 1947, a scheme expanded by the National Party administration in 1950. However, when it became clear that not enough skilled migrants would come from the British Isles alone, recruitment began in Northern European countries. New Zealand signed a bilateral agreement for skilled migrants with the Netherlands, and tens of thousands of Dutch immigrants arrived in New Zealand. Others came in the 1950s from Denmark, Germany, Switzerland and Austria to meet needs in specialised occupations.

While New Zealand did not have implicitly racist immigration legislation after the abolition of the Head Tax in 1944, the Immigration Act 1919 permitted the Minister of Immigration to arbitrarily reject immigration applications where he or she saw fit. Given the prevailing social attitudes at the time, the practical effect of the legislation was to allow the Minister to pursue an immigration policy which gave preference to persons regarded as being of adequate racial characteristics – namely, those of European ancestry. A Department of External Affairs memorandum in 1953 would state: "Our immigration is based firmly on the principle that we are and intend to remain a country of European development. It is inevitably discriminatory against Asians—indeed against all persons who are not wholly of European race and colour. Whereas we have done much to encourage immigration from Europe, we do everything to discourage it from Asia."[11][12]

By 1967, the policy of excluding people based on nationality had shifted to take account of economic needs. The economic boom of the 1960's caused a demand for unskilled labour, particularly Pacific Island workers. As such, New Zealand encouraged migrants from the South Pacific to fill labour shortages, which were pronounced in the manufacturing sector. The change in immigration policy saw Pasifika in New Zealand grow to 45,413 by 1971, with Auckland being home to the largest Polynesian population in the world.[13]

A record number of immigrants then arrived between 1971 and 1975, with net immigration exceeding 100,000 for the first time. While the overwhelming majority of migrants were from the United Kingdom and Australia, some 26,000 Pacific Islanders settled in New Zealand between 1972 and 1978, compared with 70,000 Britons and 35,000 Australians. By 1978, this trend had reversed. The decline of the New Zealand economy, marked by high inflation and rising unemployment, caused a net loss of population between 1976 and 1980, a trend that was only reversed in the 1980's. Issues of crime and housing added to increasing unease about Polynesian immigration, which was a major theme in the 1975 election campaign.[14] [15][16]

Skills-based immigration, 1980s–present

[edit]Increased multiculturalism

[edit]

Source: New Zealand Department of Labour[17]

Along with New Zealand adopting a radically new direction of economic practice, Parliament passed the Immigration Act 1987 into law. This would end the preference for migrants from Britain, Europe or Northern America based on their race, and instead classify migrants on their skills, personal qualities, and potential contribution to New Zealand economy and society. The introduction of the points-based system came under the Fourth National Government, which pursued immigration reform even more vigorously than the previous Labour government. This system closely resembled that of Canada and came into effect in 1991. The New Zealand Immigration Service now ranked the priority of immigration applications using this points-based system. In 2009, the new Immigration Act 2009 replaced all existing protocols and procedures in the 1987 Act and 1991 amendment to it.[citation needed]

The shift towards a skills-based immigration system resulted in a wide variety of ethnicities in New Zealand, with people from over 120 countries represented. Between 1991 and 1995 the numbers of those given approval grew rapidly: 26,000 in 1992; 35,000 in 1994; 54,811 in 1995. The minimum target for residency approval was set at 25,000. The number approved was almost twice what was targeted. The Labour-led governments of 1999–2008 made no change to the Immigration Act 1987, although some changes were made to the 1991 amendment.[citation needed]

In December 2002, the minimum IELTS level for skilled migrants was raised from 5.5 to 6.5 in 2002, following concerns that immigrants who spoke English as a second language encountered difficulty getting jobs in their chosen fields.[18] Since then, migration from Britain and South Africa has increased, at the expense of immigration from Asia. However, a study-for-residency programme for foreign university students has mitigated this imbalance somewhat.[citation needed]

In 2004–2005 Immigration New Zealand set a target of 45,000, representing 1.5% of the total population. However, the net effect was a population decline, since more left than arrived. 48,815 arrived, and overall the population was 10,000 or 0.25% less than the previous year. Overall though, New Zealand has one of the highest populations of foreign born citizens. In 2005, almost 20% of New Zealanders were born overseas, one of the highest percentages of any country in the world.

Subsequent amendments

[edit]The Department of Labour's sixth annual Migration Trends report showed a 21 per cent rise in work permits issued in the 2005/06-year compared with the previous year. Nearly 100,000 people were issued work permits to work in sectors ranging from IT to horticulture in the 2005/06-year. This compares with around 35,000 work permits issued in 1999–2000. Around 52,000 people were approved for permanent New Zealand residence in 2005/06. Over 60 per cent were approved under the skilled or business categories.[citation needed]

By 2005, New Zealand had accepted 60% of the applicants under the Skilled/Business category that awarded points for qualifications and work experience, or business experience and funds they had available.[citation needed]

In December 2006, the New Zealand Government published the results of an immigration review.[19]

Changes to the point system have also given more weight to job offers as compared to educational degrees. Some Aucklanders cynically joke that most taxi drivers in Auckland tend to be highly qualified engineers or doctors who are unable to then find jobs in their fields once in the country.[20]

In May 2008, Massey University economist Dr Greg Clydesdale released to the news media an extract of a report, Growing Pains, Evaluations and the Cost of Human Capital, which claimed that Pacific Islanders were "forming an underclass".[21] The report, written by Dr Clydesdale for the "Academy of World Business, Marketing & Management Development 2008 Conference" in Brazil, and based on data from various government departments, provoked highly controversial debate.[22] Pacific Islands community leaders and academic peer reviewers strongly criticised the report, while a provisional review was lodged by Race Relations Commissioner Joris de Bres.[23][24]

Tightening immigration criteria

[edit]In March 2012, a draft paper leaked to the New Zealand Labour Party showed that Immigration New Zealand was planning to create a two-tier system which would favour wealthy immigrants over poor ones who spoke little or no English. This means that applications from parents sponsored by their higher income children, or those who bring a guaranteed income or funds, would be processed faster than other applications.[25][26]

During the 2017 New Zealand general election the New Zealand First party campaigned on cutting net immigration to 10,000 per year.[27] NZ First leader Winston Peters said that unemployed New Zealanders would be trained to take jobs as the number is reduced, and the number of older immigrants will be limited, with more encouraged to settle in the regions.[28]

According to Statistics New Zealand estimates, New Zealand's net migration (long-term arrivals minus long-term departures) in the June 2016/17 year was 72,300.[29] That was up from 38,300 in the June 2013/14 year.[30] Of those migrants specifying a region of settlement, 61 percent settled in the Auckland region.[31]

In May 2022, Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern announced that the Government would be introducing a new "green list" to attract migrants for "high-skilled" and "hard-to-fill" positions from 4 July 2022. Green list applicants would have streamlined residency pathways. This Green List seeks to address skills shortages in the construction, engineering, healthcare and technology sectors.[32][33] The exclusion of nurses, teachers, and dairy farm managers from the visa residency "green list" was also criticised by the New Zealand Nurses Organisation, the Secondary Principals' Association, and Federated Farmers.[34] In early August 2022, the Government acknowledged that it had not consulted professional nursing bodies and the district health boards about its nursing "green list" visa scheme.[35] On 8 August, the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment admitted that only nine nurses had applied for the Green List visa residency scheme by late July 2022.[36]

In addition, the Government also revised its student visa policy to limit the working rights of international student holders to degree-level students and above and prevent applications from applying for a second post-study work visa in order to gain residency.[37]

In December 2022, the Government added nurses and midwives to the immigration green list, making them eligible for immediate residency in New Zealand. In addition, the Government established a temporary residence immigration pathway for bus and truck drivers. In addition teachers and tradespeople including drain layers and motor mechanics were added to the work to residence immigration pathway. These changes came in response to a national labour shortage across different sectors in the New Zealand economy.[38]

Key legislation and policies

[edit]Contemporary regulations state that immigrants must be of good character.[39]

Immigration Advisers Licensing Act 2007

[edit]Effective in New Zealand from 4 May 2007, the Immigration Advisers Licensing Act requires anyone providing immigration advice to be licensed. It also established the Immigration Advisers Authority to manage the licensing process, both in New Zealand and offshore.[citation needed]

From 4 May 2009 it became mandatory for immigration advisers practising in New Zealand to be licensed unless they are exempt.[40] The introduction of mandatory licensing for New Zealand-based immigration advisers was designed to protect migrants from unscrupulous operators and provide support for licensed advisers.

The licensing managed by the Immigration Advisers Authority Official website establishes and monitors industry standards and sets requirements for continued professional development. As an independent body, the Authority can prosecute unlicensed immigration advisers. Penalties include up to seven years imprisonment and/or fines up to $NZ100,000 for offenders, as well as the possibility of court-ordered reparation payments. It can refer complaints made against licensed advisers to an Independent Tribunal, i.e. Immigration Advisers Complaints & Disciplinary Tribunal.

The Immigration Advisers Authority does not handle immigration applications or inquiries. These are managed by Immigration New Zealand.[citation needed]

Immigration Act 2009

[edit]Statements by the government in the mid-2000s emphasised that New Zealand must compete for its share of skilled and talented migrants, and David Cunliffe, the former immigration minister, has argued that New Zealand was "in a global race for talent and we must win our share".[41]

With this in mind, a bill (over 400 pages long) was prepared which was sent to Parliament in April 2007. It follows a review of the immigration act. The bill aims to make the process more efficient, and achieves this by giving more power to immigration officers. Rights of appeal were to be streamlined into a single appeal tribunal. Furthermore, any involvement of the Human Rights Commission in matters of immigration to New Zealand would be removed (Part 11, Clause 350).

The new Immigration Act, which passed into law in 2009 replacing the 1987 Act, is aimed at enhancing border security and improving the efficiency of the immigration services. Key aspects of the new Act include the ability to use biometrics, a new refugee and protection system, a single independent appeals tribunal and a universal visa system.[42]

Other migrant quotas

[edit]New Zealand accepts 1000 refugees per year (set to grow to 1500 by 1 July 2020) in co-operation with the UNHCR with a strong focus on the Asia-Pacific region.[43]

As part of the Pacific Access Category, 650 citizens come from Fiji, Tuvalu, Kiribati, and Tonga. 1,100 Samoan citizens come under the Samoan Quota scheme. Once resident, these people can apply to bring other family members to New Zealand under the Family Sponsored stream. Any migrant accepted under these schemes receives permanent residency in New Zealand.[44]

Issues and controversies

[edit]Public opinion

[edit]As in some other countries, immigration can become a contentious issue; the topic has provoked debate from time to time in New Zealand.[citation needed]

As early as the 1870s, political opponents fought against Vogel's immigration plans.[45]

The political party New Zealand First (founded in 1993) has frequently criticised immigration on economic, social and cultural grounds.[citation needed] New Zealand First leader Winston Peters has on several occasions characterised the rate of Asian immigration into New Zealand as too high; in 2004, he stated: "We are being dragged into the status of an Asian colony and it is time that New Zealanders were placed first in their own country."[46] On 26 April 2005, he said: "Māori will be disturbed to know that in 17 years' time they will be outnumbered by Asians in New Zealand" – an estimate disputed by Statistics New Zealand, the government's statistics bureau. Peters quickly rebutted that Statistics New Zealand had underestimated the growth-rate of the Asian community in the past.[47]

In April 2008, then deputy New Zealand First Party leader Peter Brown drew widespread attention after voicing similar views and expressing concern at the increase in New Zealand's ethnic Asian population: "We are going to flood this country with Asian people with no idea what we are going to do with them when they come here."[48] "The matter is serious. If we continue this open door policy there is real danger we will be inundated with people who have no intention of integrating into our society. The greater the number, the greater the risk. They will form their own mini-societies to the detriment of integration and that will lead to division, friction and resentment."[49]

Overstayers and deportations

[edit]Between 1974 and 1979, dawn raids were carried out by the New Zealand Police to remove overstayers. These raids controversially targeted Pasifika peoples; many of whom had migrated to the New Zealand during the 1950s and 1960s due to a demand for labour to fuel the country's economic development.[50] While Pasifika comprised one-third of overstayers, they accounted for 86% of those arrested and prosecuted.[44][51] In response to domestic opposition, criticism from New Zealand's Pacific neighbours, and the failure of the raids to ease New Zealand's economic problems, the Third National Government ended the Dawn Raids in 1979.[52][53]

In 2000, the Fifth Labour Government granted an amnesty to 7,000 long-term overstayers, which allowed them to apply for New Zealand citizenship. In 2020, three separate petitions seeking an amnesty for overstayers and other changes to help migrants were submitted to the New Zealand Parliament. According to figures released by the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE) in 2017, the top five nationalities with the highest number of overstayers in New Zealand were Tongans (2,498), Samoans (1,549), Chinese (1,529), Indians (1,310), and Malaysians (790).[54] These individuals were temporary visa holders who had either not returned to their home countries once their visas had expired, renewed them, or upgraded them to residency visas. Overstayers can appeal their deportation notices to the Immigration and Protection Tribunal which has granted residency on humanitarian grounds such as family connections to New Zealand.[54][55]

In February 2022, a study published by Unitec Institute of Technology estimated there were between 13,000 and 14,000 overstayers or undocumented migrants in New Zealand, citing an interview with Immigration New Zealand Stephen Vaughan. This figure included around 500–600 Tuvaluans. These overstayers are people who have overstayed their work and study visas and been unable to renew them. Many of these overstayers have trouble accessing education, health, and social services due to their undocumented status.[56][57]

In February 2022, a report published by the Australian think tank Lowy Institute found that New Zealand had deported 1,040 people to the Pacific Islands between 2013 and 2018. Of this number, 400 were criminals including members of the Head Hunters Motorcycle Club. The report's author Jose Sousa-Santos argued that New Zealand, Australia and the United States' deportation policies were fuelling a spike in organised crime and drug trafficking in several Pacific countries including Samoa, Tonga, Fiji, Kiribati, Nauru, Tuvalu and Vanuatu. The Sousa-Santos report estimated that most of the deportees were males between the ages of 25 and 35 years, who had spent more than twelve years away from their countries of origin. Several had connections to organised crime in their former host countries.[58][59] In response to the Sousa-Santos report, Immigration Minister Kris Faafoi stated that the New Zealand Government carefully considered deportations including family and individual circumstances while retaining the right to deport those who had breached their visa conditions and the law while living and working in New Zealand.[59]

Repatriation to New Zealand

[edit]In December 2014, Peter Dutton became the new Australian Minister for Immigration and Border Protection. That same month, the Australian Government amended the Migration Act 1958 to impose a character test (known as Section 501) on non-citizens and visa applications. Under the new law, individuals who had served a prison term of at least twelve months are eligible to have their visas cancelled and be deported. Prior to 2015, Australia had deported between 50 and 85 New Zealanders per year. As Immigration Minister, Dutton swiftly implemented the new character test policy. Between 1 January 2015 and 30 August 2019, 1,865 New Zealanders were repatriated back to New Zealand. In addition, the number of New Zealanders held at Australian immigration detention centres rose to 300 in 2015.[60] By December 2019, New Zealand nationals accounted for over half (roughly 51–56%) of Australian visa cancellations.[61]

Australia has a large New Zealand diaspora community, which numbered 650,000 as of December 2019.[61] While New Zealanders are eligible for a non-permanent Special Category Visa (SCV) which allows them unique rights to live and work in Australia, SCV holders are ineligible for Australian social security benefits, student loans, and lack a clear path to acquiring Australian citizenship. Following a tightening of Australian immigration policies in 2001, New Zealanders residing in Australia were required to obtain permanent residency before applying for Australian citizenship, which led to a decline in the number of New Zealanders acquiring Australian citizenship. By 2016, only 8.4 per cent of the 146,000 New Zealand–born migrants who arrived in Australia between 2002 and 2011 had acquired Australian citizenship. Of this figure, only 3 per cent of New Zealand–born Māori had acquired Australian citizenship by 2018. During that same period the number of New Zealand-born prisoners in Australian prisons rose by 42% between 2009 and 2016.[62]

Following high-level meetings between New Zealand Prime Minister John Key and his Australian counterparts Tony Abbott and Malcolm Turnbull, the Australian Government agreed to give New Zealand authorities more warning about the repatriation of deportees and to allow New Zealanders detained at Australian immigration detention centres to fly home while they appealed their visa cancellations.[60] The Fifth National Government also passed Returning Offenders (Management and Information) Act 2015 in November 2015 which established a strict monitoring returning for 501 returnees. The law allows the chief executive of the Department of Corrections to apply to a district court to impose special conditions on returning prisoners including submitting photographs and fingerprints. While the Returning Offenders Act's strict monitoring regime reduced recidivism rates from 58% in November 2015 to 38% by March 2018, the New Zealand Law Society expressed concern that the Act potentially violated the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act 1990 by imposing "retroactive penalties and double jeopardy" on former offenders.[63][64][60]

In December 2019, Stuff reported that a total of 1,865 New Zealanders had been deported from Australia between January 2015 and August 2019. Since many former deportees lacked family ties, jobs, or homes in New Zealand, many subsequently relapsed into criminal behaviour. According to figures released by the New Zealand Police, one third of these deportees had been convicted of at least one offense since their arrival including dishonesty (1,065), traffic offenses (789), violence (578), and drugs/anti-social behaviour (394). In addition, the repatriation of New Zealanders led to a surge in organised criminal activity in New Zealand. Several repatriated members of Australian bikie gangs including the Comanchero and Mongols expanded their operations. According to Detective Superintendent Greg Williams, the repatriated "bikies" introduced a new level of "professionalism, criminal tradecraft, encrypted technologies and significant international connections" to the New Zealand criminal underworld. In addition to boosting the methamphetamine black market, the Comanchero and Mongols used social media and luxury goods to recruit young people.[65]

By early March 2022, 2,544 New Zealanders had been repatriated from Australia, which accounted for 96% of deportations to New Zealand since 2015. The repatriation of New Zealanders from Australia led to a surge in crime in New Zealand. According to Newshub, former 501 deportees accounted for more than 8,000 offences since 2015 including over 2,000 dishonesty convictions, 1,387 violent crime convictions, 861 drug and anti-social behavior offenses and 57 sexual crime offenses.[66] Both Police Commissioner Andrew Coster and New Zealand National Party leader Christopher Luxon attributed the increasingly aggressive nature of the New Zealand criminal underworld and growth in gang membership to the influx of former 501 deportees.[66][67]

On 20 December 2022, High Court Judge Cheryl Gwyn ruled in favour of a former 501 deportee known as "G," who successfully challenged the Government's authority to impose special conditions upon his return to New Zealand. Gwyn ruled that special conditions such as ordering "G" to reside at a particularly address, supplying fingerprints and DNA, and attending rehabilitative and treatment programmes violated the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act 1990 and constituted an act of double jeopardy since he had already served time for crimes in Australia which had led to his repatriation to New Zealand. Gwyn's decision has implications for the Returning Offenders (Management and Information) Act 2015, which allowed the New Zealand Government to impose special conditions on returning prisoners.[63] On 21 December, the Crown Law Office appealed against Gwyn's High Court ruling, citing its implications on the monitoring regime established by the Returning Offenders (Management and Information) Act 2015.[64]

Statistics

[edit]| Country | Gross arrivals | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | |

| 8,957 | 4,681 | 2,413 | 7,753 | 27,644 | |

| 8,338 | 2,160 | 3,048 | 9,882 | 24,780 | |

| 5,597 | 1,506 | 1,231 | 7,096 | 21,703 | |

| 16,537 | 14,614 | 14,930 | 15,587 | 10,415 | |

| 1,681 | 572 | 424 | 2,568 | 8,784 | |

| 11,185 | 7,018 | 6,481 | 6,783 | 8,181 | |

| 9,174 | 3,296 | 1,016 | 4,908 | 7,339 | |

| 4,388 | 2,912 | 2,463 | 3,639 | 5,100 | |

| 1,034 | 420 | 250 | 1,595 | 4,640 | |

| 1,075 | 420 | 191 | 780 | 4,515 | |

| 2,507 | 684 | 581 | 1,347 | 2,951 | |

| 1,065 | 679 | 629 | 1,009 | 2,701 | |

| 3,710 | 1,105 | 331 | 1,682 | 2,639 | |

| 1,074 | 639 | 906 | 1,728 | 2,465 | |

| 2,708 | 1,024 | 528 | 1,444 | 2,453 | |

| 3,220 | 859 | 498 | 1,666 | 2,406 | |

| 1,874 | 589 | 1,222 | 1,444 | 2,119 | |

| 2,733 | 1,252 | 1,128 | 1,615 | 1,897 | |

| 727 | 137 | 67 | 723 | 1,759 | |

| 1,064 | 420 | 614 | 1,594 | 1,599 | |

| 933 | 230 | 64 | 855 | 1,564 | |

| 725 | 291 | 336 | 921 | 1,536 | |

| 835 | 470 | 455 | 816 | 1,444 | |

| 580 | 143 | 223 | 573 | 1,356 | |

| 519 | 278 | 44 | 380 | 1,327 | |

| 684 | 214 | 102 | 598 | 1,068 | |

| 1,100 | 446 | 339 | 736 | 1,001 | |

| Total | 110,473 | 55,278 | 48,815 | 95,114 | 185,204 |

| Country | 2001 census | 2006 census | 2013 census | 2018 census[71] | 2023 census | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| 2,890,869 | 80.54 | 2,960,217 | 77.09 | 2,980,824 | 74.85 | 3,370,122 | 72.60 | |||

| 178,203 | 4.96 | 202,401 | 5.27 | 215,589 | 5.41 | 210,915 | 4.54 | 208,428 | ||

| 38,949 | 1.09 | 78,117 | 2.03 | 89,121 | 2.24 | 132,906 | 2.86 | 145,371 | ||

| 20,892 | 0.58 | 43,341 | 1.13 | 67,176 | 1.69 | 117,348 | 2.53 | 142,920 | ||

| 10,134 | 0.28 | 15,285 | 0.40 | 37,299 | 0.94 | 67,632 | 1.46 | 99,264 | ||

| 26,061 | 0.73 | 41,676 | 1.09 | 54,276 | 1.36 | 71,382 | 1.54 | 95,577 | ||

| 56,259 | 1.57 | 62,742 | 1.63 | 62,712 | 1.57 | 75,696 | 1.63 | 86,322 | ||

| 25,722 | 0.72 | 37,746 | 0.98 | 52,755 | 1.32 | 62,310 | 1.34 | 68,829 | ||

| 47,118 | 1.31 | 50,649 | 1.32 | 50,661 | 1.27 | 55,512 | 1.20 | 61,494 | ||

| 13,344 | 0.37 | 17,748 | 0.46 | 21,462 | 0.54 | 27,678 | 0.60 | 31,779 | ||

| 17,931 | 0.50 | 28,809 | 0.75 | 26,601 | 0.67 | 30,975 | 0.67 | 31,689 | ||

| 18,051 | 0.50 | 20,520 | 0.53 | 22,416 | 0.56 | 26,856 | 0.58 | |||

| 28,680 | 0.80 | 29,016 | 0.76 | 25,953 | 0.65 | 26,136 | 0.56 | |||

| 11,460 | 0.32 | 14,547 | 0.38 | 16,353 | 0.41 | 19,860 | 0.43 | |||

| 22,239 | 0.62 | 22,104 | 0.58 | 19,815 | 0.50 | 19,329 | 0.42 | |||

| 8,379 | 0.23 | 10,761 | 0.28 | 12,942 | 0.32 | 16,605 | 0.36 | |||

| 615 | 0.02 | 642 | 0.02 | 2,088 | 0.05 | 14,601 | 0.31 | |||

| 6,168 | 0.17 | 7,257 | 0.19 | 9,582 | 0.24 | 14,349 | 0.31 | |||

| 8,622 | 0.24 | 9,573 | 0.25 | 10,269 | 0.26 | 13,107 | 0.28 | |||

| 7,773 | 0.22 | 8,994 | 0.23 | 9,576 | 0.24 | 11,928 | 0.26 | |||

| 15,222 | 0.42 | 14,697 | 0.38 | 12,954 | 0.33 | 11,925 | 0.26 | |||

| 11,301 | 0.31 | 7,686 | 0.20 | 7,059 | 0.18 | 10,992 | 0.24 | |||

| 6,729 | 0.19 | 6,888 | 0.18 | 9,045 | 0.23 | 10,494 | 0.23 | |||

| 12,486 | 0.35 | 10,764 | 0.28 | 8,988 | 0.23 | 10,440 | 0.22 | |||

| 5,154 | 0.14 | 6,159 | 0.16 | 7,722 | 0.19 | 10,251 | 0.22 | |||

| 3,948 | 0.11 | 4,875 | 0.13 | 6,153 | 0.15 | 9,291 | 0.20 | |||

| 2,886 | 0.08 | 8,151 | 0.21 | 8,100 | 0.20 | 8,685 | 0.19 | |||

| 5,787 | 0.16 | 6,756 | 0.18 | 6,711 | 0.17 | 7,776 | 0.17 | |||

| 2,916 | 0.08 | 4,581 | 0.12 | 5,466 | 0.14 | 7,776 | 0.17 | |||

| 657 | 0.02 | 1,764 | 0.05 | 3,588 | 0.09 | 7,719 | 0.17 | |||

| 4,773 | 0.13 | 5,856 | 0.15 | 6,570 | 0.16 | 7,689 | 0.17 | |||

| 1,617 | 0.05 | 2,472 | 0.06 | 3,759 | 0.09 | 7,539 | 0.16 | |||

| 3,909 | 0.11 | 4,857 | 0.13 | 5,370 | 0.13 | 6,741 | 0.15 | |||

| 3,792 | 0.11 | 4,614 | 0.12 | 4,914 | 0.12 | 6,627 | 0.14 | |||

| 4,848 | 0.14 | 6,024 | 0.16 | 5,484 | 0.14 | 5,757 | 0.12 | |||

| 1,320 | 0.04 | 2,211 | 0.06 | 2,850 | 0.07 | 5,691 | 0.12 | |||

See also

[edit]- European settlers in New Zealand

- Demographics of New Zealand

- Europeans in Oceania

- Chinese immigration to New Zealand

- The Vogel Era

References

[edit]- ^ "History unearthed". Otago.ac.nz. University of Otago. 16 June 2014.

- ^ Germans: First Arrivals (from the Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand)

- ^ Glentanner. B. Lansley. Dornie Publishing. Invercargill 2013.

- ^ Taonga, New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage Te Manatu. "4. – History of immigration – Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand". Teara.govt.nz. Retrieved 20 July 2019.[dead link]

- ^ "Archives New Zealand || Migration". Archives.govt.nz.

- ^ Taonga, New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage Te Manatu. "6. – History of immigration – Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand". Teara.govt.nz. Retrieved 20 July 2019.[dead link]

- ^ "Pokeno Community Committee – Our Place". Pokenocommunity.nz. Archived from the original on 19 December 2018. Retrieved 10 November 2017.

- ^ "Waikato Immigration Scheme". Freepages.rootsweb.com.

- ^ Taonga, New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage Te Manatu. "5. – History of immigration – Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand". Teara.govt.nz. Retrieved 20 July 2019.[dead link]

- ^ "1881–1914: restrictions on Chinese and others". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

- ^ Quoted in Stuart William Greif, ed., Immigration and national identity in New Zealand: one people, two peoples, many peoples? Palmerston North: Dunmore, 1995, p. 39.

- ^ "Immigration and National Identity in 1970s New Zealand" (PDF). ourarchive.otago.ac.nz. Retrieved 19 March 2024.

- ^ Parker 2005, pp. 28–29.

- ^ "Immigration chronology: selected events 1840–2008". Parliament.nz. Retrieved 17 May 2016.

- ^ "Immigration regulation, Page 1". Teara.govt.nz. Retrieved 17 May 2016.

- ^ "Immigration and National Identity in 1970s New Zealand" (PDF). ourarchive.otago.ac.nz. Retrieved 19 March 2024.

- ^ "Migration Trends 2004/05" (PDF). Department of Labour. December 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 April 2008. Retrieved 8 December 2007.

- ^ "Documents confirm April consideration of language requirement change". Beehive.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 20 December 2002. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 6 November 2007.

- ^ "Comprehensive immigration law closer". Beehive.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 5 December 2006. Archived from the original on 7 March 2007. Retrieved 6 November 2007.

- ^ Collins, Simon (24 April 2007). "Migrants firm's secret weapon". The New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 14 May 2022. Retrieved 14 May 2022.

- ^ "'Islanders drain on economy' report under investigation". The New Zealand Herald. New Zealand Press Association. 24 May 2018. Archived from the original on 14 May 2022. Retrieved 14 May 2022.

- ^ "Academy of World Business, Marketing & Management Development 2008 Conference". Academy of World Business. Archived from the original on 30 August 2007. Retrieved 14 May 2022.

- ^ "Review: Pacific Peoples in New Zealand". Human Rights Commission. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 7 October 2013.

- ^ "TVNZ ondemand navigation". 1News. TVNZ. Archived from the original on 6 June 2008. Retrieved 8 June 2008.

- ^ Levy, Danya (6 March 2012). "Immigration changes give preference to wealthy". Stuff. Archived from the original on 22 December 2019. Retrieved 5 April 2012.

- ^ "Editorial – Immigration disquiet". Waikato Times. Stuff. 12 March 2012. Archived from the original on 20 February 2020. Retrieved 5 April 2012.

- ^ "Winston Peters delivers bottom-line binding referendum on abolishing Maori seats". Stuff.co.nz. 16 July 2017.

- ^ "Policy series: where do the parties stand on immigration?". The New Zealand Herald. 22 August 2017. Archived from the original on 19 November 2020. Retrieved 14 May 2002.

- ^ "National Population Estimates: At 30 June 2017". Statistics New Zealand. 14 August 2017.

- ^ "National Population Estimates: At 30 June 2014". Statistics New Zealand. 14 August 2017.

- ^ "International Travel and Migration: June 2017 – tables". Statistics New Zealand. Archived from the original on 6 September 2017. Retrieved 1 March 2018.

- ^ "New Zealand border fully reopening by July 2022". Immigration New Zealand. 11 May 2022. Archived from the original on 11 May 2022. Retrieved 12 May 2022.

- ^ Corlett, Eva (11 May 2022). "New Zealand to fully reopen borders for first time since Covid pandemic started". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 11 May 2022. Retrieved 12 May 2022.

- ^ "Shock after nurses left off fast tracked residence list". 1News. 12 May 2022. Archived from the original on 14 May 2022. Retrieved 14 May 2022.

- ^ Bonnett, Gill (3 August 2022). "DHBs not in 'targeted consultation' over Green List nursing question". Radio New Zealand. Archived from the original on 8 August 2022. Retrieved 10 August 2022.

- ^ "Nine nurses apply in first four weeks of new residency visa, MBIE figures show". Radio New Zealand. 8 August 2022. Archived from the original on 8 August 2022. Retrieved 10 August 2022.

- ^ "New Zealand border reopening fully from end of July". Radio New Zealand. 11 May 2022. Archived from the original on 11 May 2022. Retrieved 12 May 2022.

- ^ McConnell, Glenn (12 December 2022). "Government changes immigration rules for nurses, teachers and bus drivers". Stuff. Archived from the original on 12 December 2022. Retrieved 12 December 2022.

- ^ "New Zealand Visas | Immigration New Zealand". Immigration.govt.nz.

- ^ "Who can give New Zealand Immigration Advice?". Carmento. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- ^ "Where to for Immigration?". New Zealand Government. 19 November 2005. Retrieved 6 November 2007.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Immigration Act passes third reading | Scoop News". Scoop.co.nz.

- ^ "Refugee quota lifting to 1500 by 2020". Stuff.co.nz. 19 September 2018. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- ^ a b Beaglehole, Ann. "Controlling Pacific Island immigration". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 30 October 2020.

- ^ The Great Public Works Policy of 1870, – Part III by N. S Woods, in New Zealand Railways Magazine, Volume 10, 1935. "The first appropriation which Vogel asked for in 1870 was £1,500,000 for immigration. He met with opposition [...]."

- ^ "Winston Peters' memorable quotes", The Age, 18 October 2005

- ^ Berry, Ruth (27 April 2005). "Peter's Asian warning". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 4 October 2011.

- ^ "Peters defends deputy's anti-Asian immigration comments", TV3, 3 April 2008

- ^ New Zealand Herald: "NZ First's Brown slammed for 'racist' anti-Asian remarks" 3 April 2008

- ^ "The dawn raids: causes, impacts and legacy". New Zealand History. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. 15 September 2021. Archived from the original on 13 March 2022. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- ^ Cooke, Henry; Basagre, Bernadette (14 June 2021). "Government to formally apologise for race-based dawn raids". Stuff. Archived from the original on 14 June 2021. Retrieved 14 May 2022.

- ^ Mitchell, James (July 2003). Immigration and National Identity in 1970s New Zealand (PDF) (PhD). University of Otago. Retrieved 14 May 2022.

- ^ Damon Fepulea'I, Rachel Jean, Tarx Morrison (2005). Dawn Raids (documentary). TVNZ, Isola Publications.

- ^ a b Kilgallon, Steve (16 May 2021). "Illegal: How the Covid lockdown revived the role of a 'Tongan Robin Hood' last at work for overstayers in the 1980s". Stuff. Archived from the original on 28 June 2021. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- ^ "Woman who has overstayed in NZ for 16 years granted residence due to family ties". Stuff. 9 May 2022. Archived from the original on 9 May 2022. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- ^ Hoa Thi Nguyen; David Kenkel (February 2022). Hidden Gems – Lived Experiences of Tuvaluan Hope Seekers and Their Families in Aotearoa New Zealand (PDF) (Report). Unitec Institute of Technology.

- ^ "New research sheds light on undocumented families". Radio New Zealand. 10 February 2022. Archived from the original on 10 February 2022. Retrieved 19 February 2022.

- ^ Sousa-Santos, Jose (16 February 2022). "Drug trafficking in the Pacific Islands: The impact of transnational crime". Lowy Institute. Archived from the original on 17 February 2022. Retrieved 19 February 2022.

- ^ a b Stevens, Ric (20 February 2022). "New Zealand deported 400 criminals to Pacific countries over five years". The New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 24 February 2022. Retrieved 19 February 2022.

- ^ a b c Vance, Andrea; Ensor, Blair; McGregor, Iain (December 2019). "It's fashionable to beat up on New Zealand". Stuff. Archived from the original on 21 April 2021. Retrieved 3 May 2022.

- ^ a b "A Product of Australia: A three-part Stuff investigation". Stuff. December 2019. Archived from the original on 4 May 2022. Retrieved 8 May 2022.

- ^ O'Regan, Sylvia Varnham (3 July 2018). "Why New Zealand Is Furious About Australia's Deportation Policy". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 3 July 2018. Retrieved 19 July 2018.

- ^ a b Young, Audrey (20 December 2022). "Court decision on 501 deportee set to force rethink by Parliament". Radio New Zealand. Archived from the original on 27 December 2022. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- ^ a b "Crown Law appeal decision over treatment of 501 deportees". 1News. TVNZ. 21 December 2022. Archived from the original on 21 December 2022. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- ^ Vance, Andrea; Ensor, Blair; McGregor, Iain (December 2019). "Con Air: Flying to New Zealand in handcuffs". Stuff. Archived from the original on 16 March 2021. Retrieved 3 May 2022.

- ^ a b Small, Zane (5 March 2022). "Impact of Australia's 'cruel' deportations and number of 501 crimes in New Zealand revealed". Newshub. Archived from the original on 25 March 2022. Retrieved 3 May 2022.

- ^ "Luxon wants 'tough on crime' approach to 501 deportees". 1News. TVNZ. 30 March 2022. Archived from the original on 27 April 2022. Retrieved 3 May 2022.

- ^ "International travel and migration: December 2017". Statistics New Zealand. Retrieved 3 March 2018.

- ^ Stats NZ Infoshare – Table: Permanent & long-term migration by EVERY country of residence and citizenship (Annual-Dec)

- ^ "2013 Census QuickStats about culture and identity – tables". Statistics New Zealand. Archived from the original on 24 May 2014. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- ^ "2018 Census totals by topic – national highlights | Stats NZ". www.stats.govt.nz. Archived from the original on 23 September 2019. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

Bibliography

[edit]- King, Michael, 2003, The Penguin History of New Zealand, Penguin, Auckland

- McMillan, K., 2006, "Immigration Policy", pp. 639–650 in New Zealand Government and Politics, ed. R. Miller, AUP

- Parker, John (2005). Frontier of Dreams: The Story of New Zealand—Into the 21st Century, 1946–2005. Auckland: TVNZ and Scholastic. pp. 28–29, 64–65.

- History of Immigration at Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand

- News release from Caritas NZ