Interstate 40 in Tennessee

I-40 highlighted in red | ||||

| Route information | ||||

| Maintained by TDOT | ||||

| Length | 455.28 mi[1] (732.70 km) | |||

| Existed | August 14, 1957[2]–present | |||

| History | ||||

| NHS | Entire route | |||

| Major junctions | ||||

| West end | ||||

| East end | ||||

| Location | ||||

| Country | United States | |||

| State | Tennessee | |||

| Counties | Shelby, Fayette, Haywood, Madison, Henderson, Carroll, Decatur, Benton, Humphreys, Hickman, Dickson, Williamson, Cheatham, Davidson, Wilson, Smith, Putnam, Cumberland, Roane, Loudon, Knox, Sevier, Jefferson, Cocke | |||

| Highway system | ||||

| ||||

Interstate 40 (I-40) is part of the Interstate Highway System that runs 2,556.61 miles (4,114.46 km) from Barstow, California, to Wilmington, North Carolina.[1] The highway crosses Tennessee from west to east, from the Mississippi River at the Arkansas border to the Blue Ridge Mountains at the North Carolina border. At 455.28 miles (732.70 km), the Tennessee segment of I-40 is the longest of the eight states through which it passes and the state's longest Interstate Highway.[5]

I-40 passes through Tennessee's three largest cities—Memphis, Nashville, and Knoxville—and serves the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, the most-visited national park in the United States. It crosses all of Tennessee's physiographic regions and Grand Divisions—the Mississippi embayment and Gulf Coastal Plain in West Tennessee, the Highland Rim and Nashville Basin in Middle Tennessee, and the Cumberland Plateau, Cumberland Mountains, Ridge-and-Valley Appalachians, and Blue Ridge Mountains in East Tennessee. Landscapes on the route vary from flat, level plains and swamplands in the west to irregular rolling hills, cavernous limestone bluffs, and deep river gorges in the central part of the state, to plateau tablelands, broad river valleys, narrow mountain passes, and mountain peaks in the east.[6]

The Interstate parallels the older U.S. Route 70 (US 70) corridor for its entire length in the state. It has interchanges and concurrencies with four other mainline Interstate Highways, and has five auxiliary routes: I-140, I-240, I-440, I-640, and I-840. I-40 in Tennessee was mostly complete by the late 1960s, having been constructed in segments. The stretch between Memphis and Nashville, completed in 1966, was the state's first major Interstate segment to be finished. The last planned section was completed in 1975, and much of the route has been widened and reconstructed since then.

The I-40 corridor between Memphis and Nashville is known as Music Highway because it passes through a region which was instrumental in the development of American popular music. In Memphis, the highway is also nationally significant due to a 1971 U.S. Supreme Court case which established the modern process of judicial review of infrastructure projects. Community opposition to the highway's proposed routing through Overton Park led to a nearly-25-year activist campaign which culminated in the case. This resulted in the state abandoning the highway's original alignment and relocating it onto what was originally a section of I-240.

Route description

[edit]I-40 runs for 455.28 miles (732.70 km) through Tennessee, making it the second-longest stretch of Interstate Highway within a single state east of the Mississippi River.[1] It is the only Interstate Highway to pass through all three of the state's Grand Divisions and all nine physiographic regions.[6] The highway is maintained by the Tennessee Department of Transportation (TDOT). The busiest stretch of highway in Tennessee is on the segment concurrent with I-75 in Knoxville between a connector to US 11/70 and Papermill Road, which had an average daily traffic volume of 218,583 vehicles in 2022.[7] The lowest daily traffic volume that year was 26,985 vehicles at the North Carolina state line.[7] The busiest weigh station in the country is on I-40/I-75 in Farragut, a suburb of Knoxville, which serves more than 2.4 million trucks annually.[8][9]

West Tennessee

[edit]Memphis

[edit]

I-40 enters Tennessee from Arkansas in a direct east–west alignment via the six-lane Hernando de Soto Bridge, a tied-arch bridge which spans the Mississippi River and has a total length of about 1.8 miles (2.9 km).[10] Entering the city of Memphis (Tennessee's second-largest city), the Interstate crosses the southern half of Mud Island before crossing the Wolf River Harbor and Mississippi Alluvial Plain into Downtown Memphis, where the bridge ends next to the Memphis Pyramid.[11] The highway then intersects US 51 (Danny Thomas Boulevard) and, just beyond this point, abruptly turns 90 degrees north near Midtown at an interchange with the western terminus of I-240, a southern bypass route around the central city. It then intersects SR 14 (Jackson Avenue). Proceeding north, the highway crosses the Wolf River and reaches the eastern terminus of SR 300, a controlled-access connector to US 51. The Interstate then shifts due east, bypassing central Memphis to the north. Passing near the neighborhoods of Frayser and Raleigh, I-40 intersects a number of surface streets and crosses the Wolf River for a second time about five miles (8.0 km) later. It then meets SR 14 again and turns southeast.[12][13]

A few miles later, I-40 reaches a complex four-level stack interchange with US 64/70/79 (Summer Avenue) and the eastern ends of I-240 and Sam Cooper Boulevard; a pair of overpasses carries its traffic northeast. Entering a straightaway, the Interstate crosses the Wolf River for a third (and final) time; over the next several miles, it passes through the suburban neighborhoods of East Memphis and Cordova and the incorporated suburb of Bartlett in eastern Shelby County.[13] This stretch has eight lanes; the left lanes serve as high-occupancy vehicle (HOV) lanes during rush hour, and it has several interchanges with local thoroughfares.[14] The highway then intersects US 64 and narrows to four lanes.[15] After passing through Lakeland, the Interstate reaches a cloverleaf interchange with the eastern ends of I-269 and SR 385 near the suburb of Arlington.[12][13]

Gulf coastal plain

[edit]

Leaving the Memphis area, I-40 enters Fayette County east of Arlington; about five miles (8 km) later, it crosses the Loosahatchie River and adjacent wetlands. Over the next 30 miles (50 km), the Interstate crosses a level expanse of farmland and some woodlands and swamplands in a straight alignment, bypassing most cities and communities.[16] An interchange with SR 59 is at exit 35, which provides access to Covington and Somerville.[12] The highway enters Haywood County near the site of Ford Motor Company's Blue Oval City manufacturing facility.[17] Beyond this point, it turns north and enters Hatchie National Wildlife Refuge; the highway crosses the Hatchie River and a number of streams and swamps in a long straightaway. I-40 turns east after the refuge and passes southeast of Brownsville, where it intersects SR 76, SR 19, and US 70. The highway then enters Madison County.[12]

Crossing a mix of level farmland and swamplands, I-40 enters Jackson beyond this point and crosses the South Fork of the Forked Deer River.[16][18][19] Passing through northern Jackson, the Interstate widens to six lanes and has six urban interchanges.[15] In quick succession, the highway intersects US 412, which connects to Alamo and Dyersburg; the US 45 Bypass (US 45 Byp.); and US 45 (North Highland Avenue), which also provides access to Humboldt and Milan. The Interstate passes through a residential area and reaches US 70, which connects to Huntingdon. I-40 then shrinks back to four lanes.[15][20]

The highway continues east-northeast through farmland and woodlands with low, rolling hills.[12][16] After entering Henderson County, I-40 crosses the Middle Fork of the Forked Deer River.[11] It intersects SR 22, a major north–south corridor in West Tennessee which accesses Lexington and Huntington, near the town of Parkers Crossroads. The Interstate then crosses the Big Sandy River before proceeding through the northern half of Natchez Trace State Park. Over the next few miles, the highway transitions several times between Henderson and Carroll counties before entering Decatur County. It reaches US 641/SR 69, another major north–south corridor connecting Camden and Decaturville, at the Decatur–Benton county line. About six miles (10 km) later, the Interstate descends about 300 feet (100 m) on a steep grade over one mile (1.6 km) into the Western Valley of the Tennessee River; the westbound lanes have a truck-climbing lane. Entering Tennessee National Wildlife Refuge at the bottom of the grade, I-40 crosses Kentucky Lake, a Tennessee River reservoir, on the 0.5-mile (800 m) Jimmy Mann Evans Memorial Bridge into Middle Tennessee.[11][21][22]

Middle Tennessee

[edit]Western Highland Rim

[edit]

Crossing the Tennessee River into Humphreys County, I-40 exits the refuge after a few miles and traverses vast woodlands in the rugged hills of the Western Highland Rim. This section is characterized by several ascents and descents, with the route roughly following a crooked stream valley.[21][23] About six miles (10 km) beyond the river, the highway crosses the Buffalo River and intersects SR 13, which connects to Linden and Waverly. It then descends another steep grade, again with a westbound truck-climbing lane, and crosses into Hickman County.[22] It soon reaches SR 50, which connects to Centerville, and crosses the Duck River. The highway enters Dickson County several miles later, where it reaches SR 48 and access to Centerville and Dickson.[24] I-40 then crosses the Piney River.[12]

Several miles beyond this point is an interchange with SR 46, the primary exit for Dickson, which also provides access to Centerville and Columbia. Near the town of Burns, I-40 reaches the western terminus of I-840, the outer southern beltway around Nashville. The highway continues through woodlands and rugged terrain and, crossing into Williamson County, ascends steeply for a short distance with an eastbound truck-climbing lane.[12][22] Along this ascent is an interchange with SR 96, which connects to the Nashville suburbs of Fairview and Franklin.[25] The Interstate enters Cheatham County a few miles later, and gradually descends into the Nashville Basin.[26] It then passes the towns of Kingston Springs and Pegram, and crosses the Harpeth River twice in quick succession.[12]

Nashville

[edit]

Around milepost 191, I-40 enters Davidson County and crosses the Harpeth River for the third time a few miles later.[27] Entering the urbanized parts of the Nashville metropolitan area, the Interstate widens to six lanes near Bellevue.[15] The highway enters the outskirts of Nashville, the state capital and Tennessee's largest city, and intersects US 70S near a bend in the Cumberland River. It then reaches Old Hickory Boulevard (SR 251) and intersects US 70 (Charlotte Avenue) a few miles later.[27] I-40 then widens to eight lanes, and has a four-level interchange with SR 155 (Briley Parkway, White Bridge Road) which includes the western terminus of a northern controlled-access beltway around Nashville.[15] South of Tennessee State University is the western terminus of I-440, the southern loop around central Nashville, where I-40 goes down to six lanes.[15][27]

The highway briefly passes through the Jefferson Street neighborhood before entering downtown Nashville near Fisk University, where it begins a brief concurrency with I-65 and turns southeast.[12] As part of the Inner Loop encircling downtown Nashville, the two concurrent Interstates have interchanges in quick succession with US 70 (Charlotte Avenue), US 70S/431 (Broadway), Church Street, and Demonbreun Street.[28] Next they shift east-northeast near Music Row and the neighborhoods of The Gulch and SoBro, where I-65 turns south toward Huntsville, Alabama. Briefly independent for about one mile (1.6 km), I-40 crosses a viaduct and intersects US 31A/US 41A (4th Avenue, 2nd Avenue) before beginning a brief concurrency with I-24.[27] The concurrent Interstates turn southeast, expanding back to eight lanes.[15] I-24 then turns southeast towards Chattanooga, and I-40 shifts eastward. The eastern terminus of I-440 and a connector road to US 41/70S (Murfreesboro Road) are accessible from the westbound lanes of I-40 at this interchange.[12][27]

Entering the Donelson neighborhood, I-40 intersects SR 155 (Briley Parkway) near Nashville International Airport.[12][27] Beginning here, the left lanes are HOV lanes during rush hour.[14] A partial exit accesses an airport connector road; immediately beyond is a second airport access road at SR 255 (Donelson Pike). Shifting northeast, I-40 crosses the Stones River near J. Percy Priest Dam. Entering the southern fringes of the Hermitage neighborhood, the highway meets Old Hickory Boulevard again at an interchange with SR 45 and once again shifts eastward into a straightaway.[27] I-40 enters Wilson County and then has an interchange with SR 171 in the suburb of Mount Juliet. Entering another long straightaway, the highway intersects SR 109 after some distance, which provides access to Gallatin to the north. A few miles later, it has a trumpet interchange with the eastern terminus of I-840 east of Lebanon. I-40 then enters Lebanon, shrinking back to four lanes,[15] and interchanges with US 231 and US 70.[12][29]

Eastern Nashville Basin, Eastern Highland Rim, and Cumberland Plateau

[edit]The highway continues primarily across farmland for about 25 miles (40 km), passing a number of small communities.[12][16] East of Lebanon, it enters Smith County and begins a steep ascent with an eastbound truck-climbing lane.[22] Beyond this point is an interchange with SR 53 in Gordonsville and near Carthage.[12] Between mileposts 263 and 266, the highway crosses the meandering Caney Fork River five times before entering Putnam County. I-40 then again intersects SR 96 in Buffalo Valley, where it shifts southeast and begins climbing out of the Nashville Basin onto the Eastern Highland Rim.[26] The moderately-steep grade is about four miles (6.4 km) long. Near the top, the Interstate reaches an elevation of 1,000 feet (300 m) for the first time in Tennessee, close to Silver Point.[30] The highway then curves northeast and begins a concurrency with SR 56, which connects to Smithville and McMinnville to the south.[12]

I-40 then gradually shifts eastward for several miles before reaching Baxter, where SR 56 splits off and heads north toward Gainesboro. The Interstate has five interchanges in Cookeville, including one with SR 111 (a major north–south connector to Chattanooga) and another with US 70N. It then crosses Falling Water River and begins a steep, approximately five-mile (8.0 km) ascent onto the Cumberland Plateau, reaching an elevation of nearly 2,000 feet (610 m) at the top.[12] The speed limit along this section reduces to 65 mph (105 km/h) – 55 mph (89 km/h) for trucks on the westbound descent. The Interstate then continues through a wooded area before reaching Monterey and turning southeast. Here it has two interchanges with US 70N, the first of which has a concurrency with SR 84. After a few miles, the highway reaches an elevation of 2,000 feet (610 m) just before crossing into Cumberland County and East Tennessee.[12][31]

East Tennessee

[edit]Cumberland Plateau and Tennessee Valley

[edit]

After climbing the Cumberland Plateau, I-40 remains moderately flat and straight as it continues east through a mix of wooded areas and farmland.[16][31] The highway crosses the Tennessee Valley Divide, where the Cumberland and Tennessee river watersheds meet, at mile marker 308.[32] The Interstate reaches Crossville, where it crosses the Obed River, about 10 miles (16 km) later. This city has three interchanges, including one with US 127 to Jamestown.[12][33] East of Crossville, the Crab Orchard Mountains (the southern range of the Cumberland Mountains) come into view; the road descends several hundred feet, and the westbound highway has a truck-climbing lane.[34][35]

After a few miles, I-40 intersects a connector road to US 70 near the town of Crab Orchard.[12] It winds through Crab Orchard Gap, a narrow pass at the base of the Cumberland Mountains which was once prone to rockslides.[36] The Interstate then briefly ascends, with the eastbound lanes adding a truck-climbing lane.[22] At the top it enters Roane County, also transitioning from Central to Eastern Time.[33] The Interstate then curves northeast and begins a descent from the Cumberland Plateau to the Ridge-and-Valley Appalachians, also known as the Tennessee Valley or Great Valley of East Tennessee.[32] On the descent, the eastbound speed limit drops to 60 mph (97 km/h).[33] The highway hugs the slopes of the plateau's Walden Ridge escarpment for several miles, containing what the geologist Harry Moore called "dramatic views" of the Tennessee Valley, before reaching the base of the plateau about 800 feet (240 m) below.[32][37][38] I-40 then shifts eastward between Harriman and Rockwood, interchanging with US 27.[12]

The highway then crosses a series of parallel ridges and valleys characteristic of the region's topography. It intersects SR 29 and crosses the Clinch River, with the Kingston Fossil Plant and its 1,000-foot (300 m) twin smokestacks dominating the view to the north.[32][39] After an interchange with SR 58 southbound in Kingston, the Interstate begins a brief concurrency with this route. It climbs a short, relatively-steep ridge out of the Clinch River Valley, and SR 58 splits off to the north toward Oak Ridge.[38][40] Continuing through rugged terrain and across additional ridges, the Interstate enters Loudon County and intersects US 321/SR 95 near Lenoir City before reaching I-75.[12][41]

Knoxville

[edit]

I-40 merges with I-75, which continues southwest to Chattanooga, about 20 miles (32 km) west-southwest of downtown Knoxville.[12] The two routes turn east-northeast, carrying six through lanes,[15] and enter Knox County.[42] After climbing a ridge, the Interstates have a long straightaway and pass through the Knoxville suburb of Farragut.[12] The road widens to eight lanes at SR 131 (Lovell Road) and intersects the Pellissippi Parkway (SR 162 northbound, I-140 eastbound), which connects to Oak Ridge and Maryville respectively.[15] Proceeding through West Knoxville, the two routes intersect local roads before reaching a connector to US 11/70 (Kingston Pike) near the West Hills neighborhood. An interchange with SR 332 (Northshore Drive) and Papermill and Weisgarber Roads follows. The routes reach the western terminus of I-640, a beltway which bypasses downtown to the north, two miles (3.2 km) later. Here I-75 splits off from I-40 onto a brief concurrency with I-640 to Lexington, Kentucky. The Interstate then enters downtown Knoxville with six through lanes and several short segments of auxiliary lanes between exits.[12][15]

Passing near the main campus of the University of Tennessee and several residential neighborhoods, the Interstate intersects the northern terminus of US 129 (Alcoa Highway), a controlled-access highway accessing McGhee Tyson Airport and Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Next is an exit for SR 62 (Western Avenue), followed by a three-level interchange with the southern terminus of I-275; the eastbound lanes also have access to US 441 southbound (Henley Street). The highway crosses a long viaduct over a rail yard before reaching an interchange with SR 158 (James White Parkway) westbound, a controlled-access spur which accesses downtown Knoxville and the University of Tennessee to the south. I-40 then curves north and northeast before an interchange with a connector to US 441. It enters a predominantly-residential area, passing Zoo Knoxville, and reaches an interchange with US 11W (Rutledge Pike). The Interstate then reaches the eastern terminus of I-640, shifting eastward and beginning a brief, unsigned concurrency with US 25W and SR 9. These routes split off at an interchange with US 11E/70 (Asheville Highway). Leaving Knoxville, the Interstate crosses the Holston River.[12][42]

Smoky Mountains and Pigeon River gorge

[edit]

Continuing east as a six-lane highway, I-40 travels through Strawberry Plains before entering Sevier County several miles later.[15][42] Near Kodak is Exit 407 with SR 66 and the northern terminus of the Great Smoky Mountains Parkway, where the Interstate begins an unsigned concurrency with the former. This interchange is the primary access to the Great Smoky Mountains National Park and tourist attractions in Sevierville, Pigeon Forge, and Gatlinburg, and is one of Tennessee's busiest non-Interstate exits.[43] Gradually turning northeast, the highway enters Jefferson County.[12][44] After a gradual ascent of about five miles (8.0 km), the highway intersects US 25W/70 near Dandridge, where SR 66 also splits off.[45][46] It then enters northern Dandridge, where it meets SR 92. I-40 intersects the southern terminus of I-81, which runs into northeast Tennessee to the Tri-Cities of Bristol, Kingsport, and Johnson City. Here, I-40 reduces to four lanes and turns 90 degrees southeast.[15][47]

Beginning a moderate descent, the highway crosses the Douglas Lake reservoir of the French Broad River a few miles later and enters Cocke County after a gradual climb.[47][48] Near Newport is an interchange with US 25W/70, near the northern terminus of US 411.[12] Traversing the northern foothills of English Mountain, the Interstate turns south to an interchange with US 321.[49] After leaving Newport, the road crosses the Pigeon River, intersects SR 73 near Cosby, and again turns south for a view of 4,928-foot (1,502 m) Mount Cammerer at the northeastern end of the Great Smoky Mountains.[32] The highway crosses the Pigeon River again and intersects the eastern terminus of the Foothills Parkway before crossing the river a final time and curving sharply east.[12] I-40 then enters the Cherokee National Forest and snakes through the Pigeon River gorge between the Great Smoky Mountains on the south and the Bald Mountains on the north, following the river's north bank.[50][51] Due to hazardous curves, the speed limit is reduced to 55 mph (89 km/h) and trucks are prohibited from using the left lane.[52] This stretch is also prone to rockslides, and has mesh nets along some of the cliff slopes. The route gradually curves southeast near Hartford and, after several miles, crosses the Appalachian Trail and enters North Carolina.[12][53]

"Music Highway" and honorary designations

[edit]

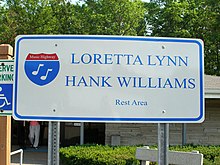

"Music Highway" refers to the section of I-40 between Memphis and Nashville, which was designated as such by the Tennessee General Assembly in 1997. The designation is "from the eastern boundary of Davidson County to the Mississippi River in Shelby County", a distance of about 222 miles (357 km). It commemorates the roles played by Memphis, Nashville, and the areas in between in the development of American popular music. Memphis is known as "the Home of the Blues and the Birthplace of Rock and Roll", and Nashville is known as "Music City" for its influence on country music. Several cities and towns between the cities, including Jackson, Brownsville, Nutbush, and Waverly, were birthplaces (or homes) of singers and songwriters. Signs with the words "Music Highway" and musical notes are along I-40 in both directions throughout this section, and rest areas are named for associated musicians or bands.[54][55]

Several sections of I-40 also bear honorary names in Tennessee. In Memphis, the freeway was designated as "Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Expressway" in 1971 after the civil rights leader who was assassinated there in 1968.[56] The stretch in eastern Shelby County was named "Isaac Hayes Memorial Highway" in 2010 after a singer-songwriter who was one of the creative forces behind Stax Records in Memphis.[57] The stretch between Nashville and Crossville was named "Senator Tommy Burks Memorial Highway" in 1999 after a state senator who was assassinated the previous year and commonly drove the route between the state capitol and his home in Cookeville.[58][59] In 1990, the segment from near Farragut to the North Carolina line was named "Troy A. McGill Memorial Highway" after a Knoxville-born U.S. Army soldier who posthumously received the Medal of Honor for his actions during the Admiralty Islands campaign in World War II.[60] The name was changed to "Troy A. McGill Medal of Honor Memorial Highway" in 2022.[61] In 2023, the stretch through Cocke County was named "Charles L. McGaha Medal of Honor Memorial Highway" after a soldier from Cosby who won the Medal of Honor for service in the 1944–1945 Philippines campaign in World War II.[62] A number of short sections, bridges, and interchanges are named for state troopers and TDOT employees killed in the line of duty, as well as local politicians and other prominent citizens.[63][64] On September 24, 2008, a monument at the Smith County Rest Area that lists the names of each TDOT worker killed in the line of duty since 1948 was dedicated.[65]

Several major bridges on I-40 also have honorary names. The "Hernando de Soto Bridge" is named for the 16th century Spanish explorer and conquistador who was the first European to cross the Mississippi River.[66] The "Jimmy Mann Evans Memorial Bridge" is named for a TDOT commissioner who served from 1987 until his death in 1992.[67] The "Samuel T. Rayburn Memorial Bridge" over the Clinch River is named for a Texas congressman who was the longest serving Speaker of the US House of Representatives.[68] The Holston River bridge is named for both Ralph K. Adcock and Bid Anderson, two state representatives from the area.[69] The "Frances Burnett Swann Memorial Bridge" across the French Broad River was designated in 1963 for the wife of Alfred Swann, who served in the Confederate Army during the American Civil War.[70]

History

[edit]Predecessor highways

[edit]

Before the settlement of Tennessee by European Americans, a series of Native American trails existed in what is now the I-40 corridor. The Cumberland Trace (also known as Tollunteeskee's Trail) was a Cherokee trail which passed through the central Cumberland Plateau, and was first used by settlers and explorers in the 1760s.[71] The North Carolina General Assembly (which controlled present-day Tennessee) authorized in 1787 construction of a trail between the southern end of Clinch Mountain (near present-day Knoxville) and the Cumberland Association, which included modern-day Nashville. Completed the following year, the trail became known as Avery's Trace and followed several Native American trails.[72] After the creation of the Southwest Territory, the territorial legislature on July 10, 1795, authorized a wagon trail to be constructed between Knoxville and Nashville. The trail, officially named the Cumberland Turnpike, became popularly known as the Walton Road for one of its surveyors: William Walton, an American Revolutionary War veteran.[71] Built from 1799 to 1801 at a cost of $1,000 (equivalent to $22,312 in 2023[73]), it was constructed from portions of Tollunteeskee's Trail, Avery's Trace, and the Emery Road (an earlier trail cleared by settlers) and passed through Kingston, Carthage, and Gallatin.[74]

In 1911, a series of Tennessee businesspeople formed the Memphis to Bristol Highway Association to encourage the state to improve the roads which ran between Memphis and Bristol.[75] After the 1915 formation of the Tennessee Department of Highways and Public Works, the predecessor to TDOT, the agency designated these roads as the Memphis to Bristol Highway,[5] and numbered them SR 1 eight years later.[76] When the United States Numbered Highway System was formed in 1926, the route connecting Memphis and Knoxville became part of US 70 and US 70S; the route from Knoxville to Bristol was designated as part of US 11 and US 11W.[75][77][78] The highway became part of the Broadway of America auto trail linking California and New York in the late 1920s.[79]

Planning

[edit]

The first segment included in Tennessee's I-40 was a 1.09-mile-long (1.75 km) controlled-access highway in Knoxville, the state's first, which was constructed by state and local governments.[80][81] Known initially as the Magnolia Avenue Expressway and later renamed the Frank Regas Expressway, the highway originated from a 1945 plan which recommended that a number of expressways be constructed in Knoxville to relieve congestion on surface streets.[81][82] Planners intended these highways to be integrated into the proposed nationwide highway network that became the Interstate Highway System, which was expected to be authorized by Congress.[83] The highway's location and design was finalized in a 1948 plan,[80][84] and construction began on October 1, 1951.[85] The first segment, between Unaka Street and Tulip Avenue, was completed on November 14, 1952;[86] the second segment, joining Tulip Avenue and Gay Street, was completed on December 10, 1955.[87] The Magnolia Avenue Expressway had a cloverleaf interchange which was reused for the intersection with I-75 (now I-275) and US 441.[80][81] This configuration quickly developed a reputation for severe congestion and a high accident rate, and became known locally as "Malfunction Junction".[80][88]

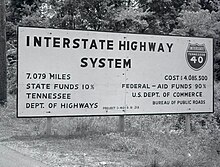

The general location of the highway which became I-40 was included in the National Interregional Highway Committee's 1944 report, "Interregional Highways",[89] and a 1947 plan produced by the Public Roads Administration of the Federal Works Agency.[90] The only area which presented a challenge to planners was the Blue Ridge Mountains, with residents of Western North Carolina divided over whether the Interstate should follow the Pigeon River or the French Broad River to the north. Surveys for both routes were authorized in 1945, and the first survey for the former was made in 1948.[91][92] After additional studies, the North Carolina Highway Commission recommended the Pigeon River gorge route in 1955;[93] this was approved by the Bureau of Public Roads (predecessor to the Federal Highway Administration) on April 12, 1956.[94] The Tennessee leg of I-40 was among 1,047.6 miles (1,685.9 km) of Interstate Highways authorized for the state by the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956, commonly known as the Interstate Highway Act.[5][95] Its numbering was approved by the American Association of State Highway Officials on August 14, 1957.[2] At 451.8 miles (727.1 km) long, I-40 in Tennessee was initially the longest segment of Interstate Highway in a single state east of the Mississippi River until an extension of I-75 in Florida was authorized by the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1968.[2][96] The first design contract for I-40 in Tennessee was awarded on March 4, 1956, for a short section in Davidson County. Within a year, design contracts had been awarded for sections in Davidson, Knox, Roane, Haywood, Madison, Jefferson, and Cocke counties. By 1958, design work was underway for most of the entire Tennessee route.[97]

Earlier construction

[edit]

The first contract for construction of I-40 in Tennessee as part of the Interstate Highway System was awarded on August 2, 1957, for a 4.8-mile (7.7 km) section in Roane County near Kingston, between the Clinch River and SR 58; construction began the following month.[99][100] Construction of I-40 between Memphis and Nashville began on September 18, 1958, in Madison County near Jackson.[101] On October 19, 1961, the bridge over the Clinch River – constructed at a cost of $2.4 million (equivalent to $18.7 million in 2023[73]) – was dedicated and opened to traffic by Governor Buford Ellington.[68] The 21.5-mile (34.6 km) section linking US 70 east of Brownsville and US 70 in Jackson, known at the time as the Jackson Bypass, was opened to traffic on December 1, 1961.[102] The following day, the 31-mile (50 km) segment opened between the Clinch River bridge in Kingston and Papermill Road in Knoxville.[103][104] On October 31, 1962, the section connecting SR 113 near Dandridge and US 25W/70 in Newport opened.[105] The first section of I-40 in Middle Tennessee to be completed was the 14.5-mile (23.3 km) stretch from SR 96 in Williamson County and US 70S in Bellevue, which opened on November 1, 1962.[106][107] The following day, the 16.5-mile (26.6 km) segment joining SR 56 near Silver Point and US 70N in Cookeville saw its first traffic.[108] The segment from US 70S in Bellevue and US 70 in western Nashville opened on November 15, 1962.[107]

In Memphis, the segment between I-240/Sam Cooper Boulevard and US 64/70/79 – then part of I-240 – was dedicated on October 9, 1963, by Governor Frank G. Clement and opened to traffic 14 days later.[109][110] That same month, contracts for the last sections between Memphis and Nashville were let.[111][112] Clement opened and dedicated the 31-mile (50 km) stretch linking SR 59 near Braden and US 70 east of Brownsville on December 17, 1963.[113] Four days later, the 15-mile (24 km) segment from SR 53 in Gordonsville to SR 56 near Silver Point opened.[114] On June 2, 1964, the nine-mile (14 km) segment connecting SR 46 in Dickson and SR 96 in Williamson County was completed.[115] The opening of the Knoxville stretch linking Papermill Road and Liberty Street was announced on September 4, 1964.[116] Two non-contiguous sections – between US 27 in Harriman and the Clinch River Bridge in Kingston, and from Liberty to Unaka Street in downtown Knoxville – were opened on December 4, 1964.[117][118] Two separate stretches, 23 miles (37 km) linking I-240 in Memphis and SR 59 in Braden, and 21 miles (34 km) connecting US 70 in Jackson and SR 22 in Parkers Crossroads, were dedicated by Clement 10 days later.[119] In Nashville, the link between Fesslers and Spence Lanes (including the eastern interchange with I-24) was declared complete on January 11, 1965.[120] The adjacent link to the west, between the western interchange with I-24 and Fesslers Lane, was partially opened in late December 1963 with the nearby Silliman Evans Bridge;[121] it fully opened on April 19, 1965.[122]

Work began on the bridge over the Tennessee River on November 29, 1962, and was completed on July 21, 1965, at a cost of $4.62 million (equivalent to $34.1 million in 2023[73]).[123] Several segments of the western portion of the 26-mile (42 km) stretch connecting Spence Lane in Nashville and US 70 in Lebanon were opened to local traffic in 1963;[121][124] the entire stretch was dedicated by Clement on August 26, 1965.[125][126] The 10.5-mile (16.9 km) segment from SR 13 in Humphreys County and SR 230 in Hickman County was completed on November 24, 1965.[123] On December 20, 1965, four segments were declared complete by the state highway department: the 19-mile (31 km) stretch connecting US 70 in Lebanon to SR 53 in Gordonsville, the eight-mile (13 km) segment from the Tennessee River to SR 13 in Humphreys County, the 11-mile (18 km) stretch linking US 70N in Cookeville and US 70N in Monterey, and the three-mile (4.8 km) segment from US 25W/70 to US 321 in Newport.[127][128] On July 24, 1966, I-40 was completed between Memphis and Nashville with the opening of the 64-mile (103 km) segment from SR 22 in Parkers Crossroads to SR 46 near Dickson after seven months of weather-related delays.[129][130] The Nashville section between US 70 and 46th Avenue was also completed.[101][131] A dedication ceremony, officiated by Clement and US Senator Albert Gore Sr., was held on the Tennessee River Bridge.[129][130] This was the first Interstate Highway segment between two major cities in Tennessee, and cost $109.87 million (equivalent to $788 million in 2023[73]).[101][132]

Later construction

[edit]The section joining US 25W/70 to SR 113 in Jefferson County, including the interchange with I-81, was completed in December 1966.[133][134] On April 11, 1967, the segment in Knoxville from Gay Street to US 11W opened.[135][136] The 16-mile (26 km) segment linking US 70N in Monterey and US 127 in Crossville opened to traffic on December 1 of that year.[137] The final section of I-40 in Knoxville to be completed was the segment connecting US 11W and US 11E/25W/70, which opened on December 19, 1967, to eastbound traffic and on June 21, 1968, to westbound traffic.[138][139] The 12-mile-long (19 km) segment from US 127 in Crossville to US 70 in Crab Orchard opened on September 12, 1968.[140] The adjacent section, extending to SR 299 near the eastern escarpment of the Cumberland Plateau, followed on September 26, 1969.[141] The section through the Pigeon River Gorge in Cocke County into North Carolina was initially believed by some engineers to be impossible to build and was among the nation's most difficult and laborious highway projects, requiring thousands of tons of earth and rock to be moved.[142] It was one of the most expensive highway construction projects per mile, at a cost of $19 million (equivalent to $127 million in 2023[73]).[143][144] Work began in 1961;[144] grading and bridge construction was complete by the end of 1964, but paving was delayed to allow additional progress in North Carolina.[145] On October 24, 1968, the 37-mile (60 km) stretch between US 321/SR 32 in Newport and US 276 in Haywood County, North Carolina, was opened to traffic by both states with a dedication ceremony.[146]

In Nashville, the segment linking 46th Avenue with I-65 opened to traffic on March 15, 1971.[147] The Memphis section from US 51 to Chelsea Avenue, including the Midtown interchange with I-240 (then I-255), opened on July 14 of that year.[148] Work on the final segment between Memphis and Knoxville, approximately 5.5 miles (8.9 km) from the interchange with I-65 to the western split with I-24 southeast of downtown Nashville (including the concurrency with I-65), began in May 1969 and opened on March 3, 1972. This completed all of I-40 from Memphis to SR 299, near Rockwood, and the last stretch in Middle Tennessee.[149] The last segment of the planned I-40 in West Tennessee to be completed was the Hernando de Soto Bridge in Memphis; construction began on May 2, 1967, and the bridge opened to traffic on August 2, 1973.[150][151] The bridge, which cost $57 million (equivalent to $299 million in 2023[73]), was dedicated by Tennessee Governor Winfield Dunn and Arkansas Governor Dale Bumpers on August 17, 1973.[152][153]

The nine-mile (14 km) segment from SR 299 to US 27 near Harriman and Rockwood, including the descent down Walden Ridge, was the last section of I-40 completed between Memphis and Knoxville, and was repeatedly delayed by geological problems. The westbound lanes opened to two-way traffic on November 18, 1972,[154][155] and the complete section opened on August 19, 1974.[156] Work started on this section in early 1966, and was originally expected to be completed by late 1968.[157] The final segment of the planned route of I-40 in Tennessee, 21.5 miles (34.6 km) connecting US 11E/25W/70 east of Knoxville to US 25W/70 in Dandridge, was dedicated by Dunn and partially opened to traffic on December 20, 1974;[158][159] it fully opened on September 12, 1975.[3] Initially planned with four lanes, engineers chose to expand this segment to six lanes in 1972 after construction had begun, based on studies projecting a higher-than-average traffic volume.[160] This segment, one of the nation's first rural six-lane highways, was also dedicated on the same day that the last sections of I-75 and I-81 in Tennessee were opened.[158][161] The last section of I-40 in Tennessee to be completed linked Chelsea Avenue and US 64/70/79 in Memphis, and was originally part of I-240.[162] Due to its location within a floodplain, an artificial fill of 23 million cubic yards (18×106 m3) of sand and silt was required for the roadbed, most of which was dredged and pumped from the bottom of the Mississippi River via a pipeline.[163][164] Contracts for this work were let in May and July 1974.[165][166] Dredging and fill work was complete by the end of 1977,[167][168] and the section was opened to traffic by Governor Lamar Alexander on March 28, 1980.[162]

Controversies

[edit]

I-40 was originally planned to pass through Overton Park in Memphis, a 342-acre (138 ha) public park. This location was announced in 1955, and was approved by the Bureau of Public Roads in November 1956.[169][170] The park consists of a wooded refuge, the Memphis Zoo, the Memphis Brooks Museum of Art, the Memphis College of Art, a nine-hole golf course, an amphitheater which was the site of Elvis Presley's first paid concert in 1954, and other amenities. When the state announced the routing through the park, a group of local citizens spearheaded by a group of older women called "little old ladies in tennis shoes" by media outlets began a campaign to halt construction. The organizers collected over 10,000 signatures, and founded Citizens to Preserve Overton Park in 1957.[171] The movement was also backed by environmentalists, who feared that the Interstate's construction would upset the park's ecological balance; the wooded area had become an important stopover for migratory birds.[172]

The organization filed a lawsuit in the US District Court for the Western District of Tennessee in December 1969 after the Secretary of Transportation John A. Volpe authorized the state to solicit bids the previous month.[173] The suit was dismissed on February 26, 1970, by Judge Bailey Brown,[174] which was subsequently upheld by the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals on September 29, 1970.[175] The case was then appealed to the US Supreme Court, which reversed the lower-court rulings in the landmark decision of Citizens to Preserve Overton Park v. Volpe on March 2, 1971. The court found that Volpe had violated clauses of the Department of Transportation Act of 1966 and the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1968, which prohibit the approval of federal funding for highway projects through public parks with feasible alternative routes.[169] Tennessee continued exploring options to route I-40 through Overton Park for many years after this decision including tunneling under the park or constructing the highway below grade, but concluded that the alternatives were too expensive.[170][176] On January 9, 1981, Governor Alexander submitted a request to Secretary of Transportation Neil Goldschmidt to cancel the route through Overton Park, which was approved seven days later.[177][178]

On June 28, 1982, the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials approved an application by TDOT to redesignate the northern portion of I-240 as the remainder of I-40;[179] this added about 3.4 miles (5.5 km) to the route.[11][180] About four miles (6.4 km) of a controlled-access highway was built within the I-240 loop east of the park before the cancellation; this portion of highway was named Sam Cooper Boulevard in December 1986,[181] and terminates at East Parkway in the Binghampton neighborhood near the park.[13] Right-of-way was also acquired west of the park, and many structures were demolished to make way for the Interstate; some of these empty lots have since been built on.[182] When the route was canceled, about $280 million (equivalent to $795 million in 2023[73]) had been budgeted by the federal government for its construction; these funds were then diverted for other transportation improvements in the Memphis metropolitan area.[178][182]

I-40 passes through the Jefferson Street community in western Nashville, a predominantly Black neighborhood which contains three historically Black colleges and was home to a large African American middle class in the early-to-mid-20th century.[183][184] Planners considered placing this section near Vanderbilt University, but settled on the current alignment by the mid-1950s.[185] Before construction began, many residents believed that the Interstate would lead to the economic decline of their neighborhood and divide it from the rest of the city.[185] Some also believed that the routing was an act of racial discrimination, and criticized the state for a lack of transparency about its plans.[185] In October 1967, several residents of Jefferson Street formed the I-40 Steering Committee and filed a lawsuit against the state in the US District Court for the Middle District of Tennessee in the hope forcing a reroute of the Interstate.[185] Judge Frank Gray Jr. ruled against the committee on November 2, saying that there was no feasible alternate route.[186] Gray conceded, however, that the methods used by the state to notify residents about the project were unsatisfactory and the route would have an adverse effect on their community.[185] The organization appealed the decision to the Sixth Circuit, which unanimously upheld the lower court's decision on December 18; and to the Supreme Court, which refused to hear the case on January 29, 1968.[186] The construction of I-40 through Jefferson Street resulted in many Black residents being displaced to the Bordeaux area of North Nashville, and led to the predicted economic downturn in the neighborhood.[187][188]

Major projects and expansions

[edit]Memphis projects

[edit]

The first high-occupancy vehicle (HOV) lanes in the Memphis area opened on September 15, 1997, on the 7.5-mile (12.1 km) section between I-240 and US 64 in Bartlett with the completion of a project widening the section from four to eight lanes.[189] The cancellation of the section of I-40 through Overton Park rendered both interchanges with I-240 inadequate to handle the unplanned traffic patterns, necessitating their reconstruction;[182] both interchanges also contained ramps with hazardously sharp curves.[190] The eastern interchange was reconstructed with two projects.[191] The first, which began in January 2001 and finished in October 2003, constructed a two-lane overpass from I-40 westbound to I-240 westbound; this replaced a one-lane loop ramp and widened the approach of I-240 south of the interchange.[192][193] I-40 north of the interchange was also reconstructed in preparation for the second project, and the interchanges with US 64/70/79 (Summer Avenue) and White Station Road were modified.[191]

The second project, initially scheduled to begin in January 2004,[191] was delayed until October 2013 due to funding and redesign complications.[194] A two-lane overpass was built to carry I-40 eastbound traffic through the interchange, replacing a one-lane ramp. The single-lane ramp carrying I-40 westbound traffic through the interchange was repurposed as the exit ramp for Summer Avenue, and was replaced with a two-lane overpass connecting to the overpass constructed in the first project. This project also widened the ramp connecting I-240 eastbound and I-40 eastbound to three lanes, widened both approaches to the interchange on I-40, which required a new 14-lane bridge over the Wolf River, widened the approach on I-240 south of the interchange, added through lanes to Sam Cooper Boulevard, and reconfigured the SR 204 (Covington Pike) interchange.[195] It cost $109.3 million (equivalent to $136 million in 2023[73]), the most expensive contract in state history at the time,[194] and was completed on December 15, 2016.[196][197]

The interchange with the western terminus of I-240 near midtown Memphis was reconstructed between June 2003 and December 2006.[198] This project converted the interchange into a directional T configuration, which required the demolition of several unused ramps and bridges which had been built in the expectation that I-40 would continue east of the interchange.[199] The nearby cloverleaf interchange with SR 14 (Jackson Avenue) was reduced to a partial cloverleaf interchange, and several additional auxiliary lanes and slip ramps were constructed. The northern merge point between I-40 and I-240 was moved north of the SR 14 interchange.[200]

Nashville area

[edit]

In November 1977, TDOT installed a system to detect tailgating vehicles in the westbound lanes of the concurrent segment with I-24: sensors embedded in the roadway which were connected to overhead warning signs with flashing lights and horns.[201][202] The system (the first of its kind in the country) experienced technical problems, was criticized as ineffective, and was decommissioned in July 1980.[203] This segment of I-40 was widened from six to eight lanes between July 1979 and January 1980 by removing the right shoulders, narrowing the lanes by one foot (30 cm), and shifting traffic slightly to the left.[204][205]

The short segment of I-40 from east of the split with I-24/I-440 and east of SR 255 (Donelson Pike) in eastern Nashville was widened to six lanes from August 1986 to December 1987.[206] From October 1987 to November 1989, the 4.7-mile (7.6 km) segment from east of SR 255 to east of SR 45 was widened from four to eight lanes.[207] West of downtown Nashville, the three-mile (4.8 km) section between SR 155 (Briley Parkway/White Bridge Road) and US 70 (Charlotte Pike) was expanded to six lanes from February 1988 to December 1989. From April 1991 to December 1992, the 5.9-mile (9.5 km) section in Bellevue linking US 70 and US 70S was widened to six lanes.[208]

The first HOV lanes on I-40 in Tennessee were opened to traffic on November 14, 1996, with the completion of a project which widened the eight-mile (13 km) section between west of SR 45 (Old Hickory Boulevard) in eastern Nashville and east of SR 171 in Mount Juliet from four to eight lanes.[209] They were Tennessee's second set of HOV lanes.[210] The project, which began in early 1995, was the state's first to use split Jersey barriers in the median every few miles to allow police enforcement from the left shoulder.[211] The short stretch between SR 155 (Briley Parkway/White Bridge Road) and the western terminus of I-440 was modified from November 2002 to July 2005; it was widened to eight through lanes, auxiliary lanes were added, access to local thoroughfares was improved and expanded, and two overpasses provided partial access control to the southern end of Briley Parkway.[212][213] The second phase (from July 2009 to August 2011) constructed an overpass between I-40 and Briley Parkway, converting the interchange to full access control, modified the White Bridge Road interchange, and widened a short stretch of I-40 west of the interchange.[214][215]

A project from January 2004 to January 2007 widened the three-mile (4.8 km) section connecting I-24/440 to SR 255 from six to eight through lanes, added auxiliary lanes between interchanges, and reconstructed the interchange with SR 155 (Briley Parkway) for controlled access.[216][217] Work to widen six miles (9.7 km) of I-40 from four to eight lanes from east of SR 171 to east of SR 109 in Lebanon began in July 2012 and was completed in July 2014.[218][219] The four-mile (6.4 km) stretch from east of SR 109 to east of I-840 in Lebanon was widened from four to eight lanes between April 2019 and September 2021.[220][221]

Knoxville projects

[edit]

Beginning in early May 1980, the segment of I-40 in Knoxville between Papermill Road and Gay Street was modified in a project which modified the interchanges with 17th Street, Western Avenue, and Gay Street; widened the segment to a minimum of six through lanes; added frontage roads; and reconstructed the gridlock-prone cloverleaf interchange with I-75 known as "Malfunction Junction" into a stack interchange with overpasses.[222][223] The non-contiguous segment between US 11W (Rutledge Pike) and US 11E/25W/70 (Asheville Highway) was also widened to six lanes.[224] Work was completed on March 30, 1982, with a ceremony officiated by Governor Alexander.[225] While these projects were underway, the concurrent part of I-75 on this segment was rerouted around the western leg of I-640 (completed in December 1980) and the short segment of I-75 north of this segment became I-275.[226] These projects were part of a $250 million (equivalent to $668 million in 2023[73]) multi-phase improvement project for area roads which was accelerated in preparation for the 1982 World's Fair.[227][228] They were followed by widening I-40 to six lanes between Broadway and US 11W from July 1990 to October 1991.[208][229]

By the mid-1970s, the concurrent segment of I-40 with I-75 between Lenoir City and western Knoxville was congested. The FHWA authorized TDOT in 1978 to widen the section from the I-75 interchange near Lenoir City to the Pellissippi Parkway to six lanes and the segment from the Pellissippi Parkway to I-640 to eight lanes, and to reconstruct interchanges along this section. TDOT announced plans to proceed with the project in May 1981, initially choosing to widen the entire segment to six lanes due to the need for immediate congestion relief and additional right-of-way required by the larger project.[230] The six-lane project began in July 1984 with the segment between Papermill Road and the Pellissippi Parkway, and was completed in December 1985.[231] The remainder of the project, located between the Pellissippi Parkway and the I-75 split, was done from June 1985 to July 1986.[232]

On October 9, 1986, the FHWA approved an environmental impact statement (EIS) for the remainder of the I-40/I-75 improvement project.[230] The first phase, between August 1990 and August 1994, widened the section east of the Pellissippi Parkway and east of Cedar Bluff Road and reconstructed the Cedar Bluff Road interchange.[233][234] In preparation for the second phase, Gallaher View Road was extended north to the Interstate between April 1994 and July 1996 with a new overpass and on-ramp.[235][236] The second phase, from May 1996 to December 1999, widened the section from east of Cedar Bluff Road to east of Gallaher View Road and extended Bridgewater Road to the Interstate.[237][238] The interchange with Walker Springs Road was replaced, providing access to all three roads via collector–distributor frontage roads.[235] The third phase, from early 2000 to late 2002, widened the segment linking Papermill Road to I-640 from six to 10 lanes. The fourth phase, from September 2000 to July 2003, improved the interchange with SR 131 and widened the section to the Pellissippi Parkway.[239] The final phase, from January 2003 to December 2006, widened the section connecting Gallaher View Road to Papermill Road and reconfigured the interchanges with the US 11/70 connector and Papermill Road.[240][241] A collector–distributor facility serving the westbound ramps was built along the Papermill interchange, and ramps to Weisgarber Road and SR 332 were constructed.[242]

In 1989, TDOT began preliminary planning work to widen the four-lane section from east of I-275 to Broadway/Hall of Fame Drive, and reconstruct the accident-prone interchange with SR 158 (James White Parkway), which contained left-hand entrance and exit ramps. Preliminary engineering began in 1995, and the FHWA approved an EIS for the project on February 28, 2002.[243] On June 14, 2004, the two-phase project was unveiled to the public with the name SmartFIX40.[244] The first phase, from July 6, 2005, to September 21, 2007,[245] rebuilt and realigned the interchanges with SR 158, Broadway/Hall of Fame Drive, and Cherry Street; and built collector–distributor ramps between these interchanges.[246][247] For the second phase, I-40 between SR 158 and Broadway/Hall of Fame Drive was closed between May 1, 2008, and June 12, 2009.[248] This allowed crews to widen this section to six lanes with additional auxiliary lanes and rebuild the SR 158 interchange on an accelerated timeline.[249] Through traffic used I-640 or surface streets during the closure, and inbound and outbound ramps connecting I-40 and I-640 at both interchanges were temporarily widened to three lanes to accommodate the extra volume.[250] Both phases of SmartFIX40 received an America's Transportation Award from the AASHTO in 2008 and 2010.[251][252] At a cost of $203.7 million (equivalent to $281 million in 2023[73]), SmartFIX40 was the largest project ever coordinated by TDOT at the time and the second of its kind in the US.[253]

Other projects

[edit]

Between July 1997 and November 1999, the six-mile (9.7 km) section from US 25W/70 to I-81 in Jefferson County was widened to six lanes.[254] A 2008 TDOT study of the I-40 and I-81 corridors identified a number of steep grades which were difficult for trucks to climb, causing congestion and safety hazards, and the department constructed truck climbing lanes throughout the corridor in response. In 2018, three westbound truck lanes – a two-mile-long (3.2 km) lane immediately west of the Tennessee River in Benton County, a two-mile (3.2 km) lane in Humphreys and Hickman counties, and a one-mile (1.6 km) lane east of Crossville – were completed.[35][255][256] Two additional projects, a four-mile (6.4 km) lane in Dickson and Williamson counties and a three-mile (4.8 km) lane in western Smith County (both eastbound), were completed the following year.[256] In 2020, a truck lane was built on a two-mile (3.2 km) eastbound segment in eastern Cumberland County.[257]

In Jackson, I-40 was widened to six lanes and interchanges were improved in three phases. The first phase, which began on October 2, 2017, widened I-40 between west of US 45 Byp. and east of US 45, a distance of about 2.9 miles (4.7 km); added auxiliary lanes between these interchanges and the interchange with US 412; converted the cloverleaf interchange with the US 45 Byp. into a partial cloverleaf interchange and the cloverleaf with US 70 into a single-point urban interchange (SPUI); and replaced bridges and improved intersections on both routes near the interchanges.[258][259] The first phase finished in early July 2021.[260] The second phase, which began on November 4, 2020, widened I-40 from east of US 45 to east of US 70/412, a distance of about 5.5 miles (8.9 km), added auxiliary lanes, and replaced bridges.[261] It was completed on November 7, 2022.[262] The final phase, which began on July 10, 2022, and was completed ahead of schedule on December 13, 2023, widened the 1.2-mile (1.9 km) segment from west of US 412 to west of US 45 Byp.[263]

Geological difficulties

[edit]East Tennessee's rugged terrain presented a number of challenges to I-40 construction crews and engineers. Rockslides, especially along the eastern Cumberland Plateau and in the Pigeon River gorge, have been a persistent problem during and since the road's construction.[36]

Crab Orchard and Walden Ridge area

[edit]On December 17, 1986, a truck driver was killed when his truck struck a boulder which had fallen across the road just east of Crab Orchard.[264] In response to the incident, between January 1987 and December 1988, workers flattened the cut slopes along this stretch of the Interstate and moved a 1,000-foot (300 m) section of the road 60 feet (18 m) from the problematic cliffside.[36][265]

While I-40 was under construction, 20 rockslides occurred along the Walden Ridge section (miles 341–346) of the eastern plateau in 1968. This prompted remedial measures throughout the 1970s, including rock buttresses, gabion walls, and horizontal drains.[36] Minor rockslides shut down the westbound lanes of this section on June 20, 1989, and on May 6, 2013.[266][267]

Pigeon River gorge

[edit]

The Pigeon River gorge is prone to rockslides, especially near the Tennessee–North Carolina state line.[268] This stretch of I-40 was repeatedly shut down by rockslides during the 1970s, sometimes for weeks at a time. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, workers dug over 24,000 feet (7,300 m) of horizontal drains, blasted out a large number of unstable rocks, and installed mesh catchment fences.[36] However, rockslides in 1985 and 1997 again forced the closure of I-40 in the Pigeon River gorge for several weeks.[269] Additional stabilization measures were implemented, including the blasting of loose rock, the installation of rock bolts, and improved drainage.[270] Another rockslide in the gorge on October 26, 2009, blocked all lanes just across the border at North Carolina mile 3; the section was closed to traffic in both directions until April 25, 2010.[271] On January 31, 2012, the westbound lanes of I-40 were closed for a few weeks because of a rockslide near the North Carolina border.[272] Torrential flooding in the Pigeon River from the aftermath of Hurricane Helene washed away a small section of the eastbound shoulder and embankment near the state line on September 27, 2024, closing the roadway to all traffic.[273]

Sinkholes

[edit]Sinkholes are a consistent issue along highways in East Tennessee. One particularly problematic stretch is a section of I-40 between miles 365 and 367 in Loudon County, which is underlain by cavernous rock strata. TDOT employed a number of stabilization measures in this area during the 1970s and 1980s, including backfilling existing sinkholes with limestone, collapsing potential sinkholes, and paving roadside ditches to prevent surface water from seeping into unstable soil.[36]

Incidents and closures

[edit]On December 23, 1988, a tanker truck hauling liquified propane overturned on a one-lane ramp carrying I-40 traffic through the Midtown interchange with I-240 in Memphis, poking a small hole in the front of the tank.[274][275] The leaking gas ignited in a boiling liquid expanding vapor explosion (BLEVE), producing a fireball that set nearby vehicles and structures on fire and instantly killed five motorists (including the truck driver).[276][277] The tank was propelled from the crash site by the remaining combusting gas, striking a nearby overpass and crashing into a duplex apartment about 125 yards (114 m) away. One occupant was killed, and additional fires spread to other buildings.[278] A total of seven additional cars were destroyed, and 10 cars, six houses, and a residential complex were damaged.[276] Ten people were injured, and two people who were inside of homes impacted by the fires later died from their injuries.[279] Another truck driver was killed when he crashed into a traffic jam caused by the accident.[280] This event, one of Tennessee's deadliest and most destructive motor-vehicle accidents, spurred the eventual reconstruction of the interchange.[198]

Inspectors discovered a crack on a tie girder of the Hernando de Soto Bridge on May 11, 2021, resulting in the closure of the bridge.[281] A subsequent investigation indicated that the crack had existed since at least May 2019, and reports later surfaced that the crack had probably existed since August 2016.[282][283] TDOT awarded an emergency repair contract for the bridge on May 17, 2021, and the repair was made in two phases.[284][285] In the first phase, completed on May 25, 2021, fabricated steel plates were attached to both sides of the fractured beam.[286] The second phase consisted of the installation of additional steel plating and removal of part of the damaged beam.[284] The bridge's eastbound lanes reopened on July 31, 2021,[287] and the westbound lanes reopened two days later.[288] A report released later that year concluded that the crack resulted from a welding flaw during the beam's fabrication.[289]

Exit list

[edit]| County | Location | mi[290][a] | km | Exit | Destinations | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mississippi River | 0.00– 1.18 | 0.00– 1.90 | Continuation into Arkansas | |||

| Hernando de Soto Bridge Tennessee–Arkansas line | ||||||

| Shelby | Memphis | 0.92 | 1.48 | 1 | Front Street, Riverside Drive – Downtown Memphis | Western end of Music Highway designation |

| 1.09– 1.16 | 1.75– 1.87 | 1A | Second Street, Third Street (SR 3, SR 14) | Westbound exit and eastbound entrance | ||

| 1.55 | 2.49 | 1B | Signed as exits 1C (south) and 1D (north) westbound | |||

| 2.23– 2.69 | 3.59– 4.33 | 1E | East end of I-55 Alt. concurrency; I-240 exit 31; former I-255 south; semi-directional T interchange; I-240 serves Memphis International Airport; westbound ramp to I-240 southbound and ramp from I-240 northbound to I-40 eastbound merge north of exit 1F via collector–distributor facilities | |||

| 3.13 | 5.04 | 1F | Westbound exit and eastbound entrance | |||

| 3.89– 4.14 | 6.26– 6.66 | 2 | Chelsea Avenue, Smith Avenue | |||

| 4.78– 5.49 | 7.69– 8.84 | 2A | Access via unsigned SR 300 west; directional-T interchange | |||

| 5.51 | 8.87 | 3 | Watkins Street | |||

| 7.44 | 11.97 | 5 | Hollywood Street | |||

| 8.60 | 13.84 | 6 | Warford Street | |||

| 10.42 | 16.77 | 8 | Signed as exits 8A (north) and 8B (south) westbound | |||

| 12.50 | 20.12 | 10 | ||||

| 13.37– 14.39 | 21.52– 23.16 | 12A | Eastbound exit only; westbound access via Sam Cooper Blvd. | |||

| 14.39 | 23.16 | 10A | Westbound exit follows Sam Cooper Blvd. numbering; no exit number eastbound; I-240 exit 12C; four-level stack interchange | |||

| 14.39 | 23.16 | — | Sam Cooper Boulevard | Westbound left exit and eastbound left entrance | ||

| 15.67 | 25.22 | 12 | Sycamore View Road – Bartlett | |||

| 17.27 | 27.79 | 14 | Whitten Road | |||

| 18.79 | 30.24 | 15 | Appling Road | Signed as exits 15A (south) and 15B (north) eastbound | ||

| 20.15 | 32.43 | 16 | Signed as exits 16A (south) and 16B (north) westbound | |||

| Memphis–Bartlett line | 21.47 | 34.55 | 18 | |||

| Lakeland | 23.87 | 38.42 | 20 | Canada Road – Lakeland | ||

| Arlington | 27.95 | 44.98 | 24 | Signed as exits 24A (south) and 24B (north); I-269 exit 19; cloverleaf interchange | ||

| 28.74 | 46.25 | 25 | ||||

| Fayette | Hickory Withe–Gallaway line | 32.48 | 52.27 | 28 | ||

| | 38.90 | 62.60 | 35 | |||

| | 39 | To serve an extension of SR 194 for Blue Oval City[17][291] | ||||

| | 45.80 | 73.71 | 42 | |||

| Haywood | | 51.25 | 82.48 | 47 | ||

| | 55.72 | 89.67 | 52 | |||

| Brownsville | 59.028 | 94.996 | 56 | |||

| | 62.60 | 100.74 | 60 | |||

| | 68.35 | 110.00 | 66 | |||

| Madison | | 70.68 | 113.75 | 68 | ||

| | 77.11 | 124.10 | 74 | Lower Brownsville Road | ||

| Jackson | 78.81 | 126.83 | 76 | |||

| 81.57 | 131.27 | 79 | ||||

| 82.83 | 133.30 | 80 | Signed as exits 80A (south) and 80B (north) | |||

| 84.29 | 135.65 | 82 | Formerly signed as exits 82A (south) and 82B (north) | |||

| 85.56 | 137.70 | 83 | Campbell Street, Old Medina Road | Opened June 13, 2003[292] | ||

| 87.15 | 140.25 | 85 | Christmasville Road, Dr. F.E. Wright Drive – Jackson | Opened December 14, 1987[293] | ||

| | 89.31 | 143.73 | 87 | |||

| | 95.87 | 154.29 | 93 | |||

| Henderson | | 103.11 | 165.94 | 101 | ||

| Parkers Crossroads | 110.34 | 177.58 | 108 | |||

| Henderson–Carroll county line | | 118.47 | 190.66 | 116 | ||

| Decatur–Benton county line | | 128.34 | 206.54 | 126 | ||

| Benton | | 135.42 | 217.94 | 133 | ||

| Tennessee River | 136.82– 137.32 | 220.19– 221.00 | Jimmy Mann Evans Memorial Bridge | |||

| Humphreys | | 139.14 | 223.92 | 137 | Cuba Landing | |

| | 145.30 | 233.84 | 143 | |||

| Hickman | | 150.64 | 242.43 | 148 | ||

| Bucksnort | 154.92 | 249.32 | 152 | |||

| Dickson | | 166.19 | 267.46 | 163 | ||

| Dickson | 175.19 | 281.94 | 172 | |||

| | 179.29 | 288.54 | 176 | Western terminus and exits 1A-B on I-840; former SR 840; half-cloverleaf interchange | ||

| Williamson | Fairview | 184.58 | 297.05 | 182 | ||

| Cheatham | Kingston Springs | 190.53 | 306.63 | 188 | ||

| Davidson | Nashville | 195.22 | 314.18 | 192 | McCrory Lane – Pegram | |

| 199.01 | 320.28 | 196 | ||||

| 201.76 | 324.70 | 199 | ||||

| 203.60 | 327.66 | 201 | Signed as exits 201A (east) and 201B (west) eastbound | |||

| 206.39 | 332.15 | 204 | Signed as exits 204A (north) and 204B (south) westbound; SR 155 exit 6; four-level stack interchange | |||

| 206.93– 207.31 | 333.02– 333.63 | 205 | 51st Avenue, 46th Avenue – West Nashville | |||

| 208.17– 208.61 | 335.02– 335.73 | 206 | Left exit westbound; semi-directional T interchange | |||

| 208.88 | 336.16 | 207 | 28th Avenue | Westbound exit and eastbound entrance | ||

| 209.33 | 336.88 | Jefferson Street | Eastbound exit and westbound entrance | |||

| 209.91– 210.28 | 337.82– 338.41 | 208 | Left exit eastbound, left entrances; signed as exit 208B eastbound; western end of I-65 overlap; I-65 exit 84B southbound; former I-265; directional-T interchange | |||

| 211.00 | 339.57 | 209 | Church St. not signed eastbound | |||

| 211.20 | 339.89 | 209A | Church Street | Eastbound signage Westbound signage | ||

| 211.38– 211.52 | 340.18– 340.41 | 209B | Westbound signed as "Demonbreun St." only | |||

| 212.04– 212.52 | 341.25– 342.02 | 210 | Eastern end of I-65 overlap; left exit and entrance westbound; signed as exit 210B westbound; I-65 exit 82B northbound; directional-T interchange | |||

| 212.71– 212.83 | 342.32– 342.52 | 210C | ||||

| 213.10– 213.48 | 342.95– 343.56 | 211 | Western end of I-24 overlap; left exit and entrance eastbound; signed as exit 211B eastbound; I-24 exit 50B eastbound; former I-65 north; directional-T interchange | |||

| 213.91 | 344.25 | 212 | Hermitage Avenue | Westbound exit; eastbound entrance from Green Street; access to unsigned US 70 | ||

| 214.42 | 345.08 | Fesslers Lane | Eastbound exit and westbound entrance | |||

| 215.21– 215.78 | 346.35– 347.26 | 213A | Eastern end of I-24 overlap; eastbound exit and westbound left entrance; directional-T interchange | |||

| Westbound left exit and eastbound entrance; I-24 exit 52B | ||||||

| 215.78 | 347.26 | 213 | Westbound exit only; eastbound access via exit 213A | |||

| 217.28 | 349.68 | 215 | Signed as exits 215A (south) and 215B (north); SR 155 exit 27 southbound; not signed northbound; cloverstack interchange | |||

| 218.42 | 351.51 | 216A | Eastbound exit and westbound entrance | |||

| 219.11 | 352.62 | 216B | ||||

| 216C | ||||||

| 221.55 | 356.55 | 219 | Stewarts Ferry Pike – J. Percy Priest Dam | |||

| 222.51 | 358.10 | 221A | Eastbound exit and westbound entrance; Eastern end of Music Highway designation | |||

| 223.41 | 359.54 | 221B | Old Hickory Boulevard | |||

| Wilson | Mount Juliet | 228.49 | 367.72 | 226 | Signed as exits 226A (SR 171 south), 226B (SR 171 north), and 226C (Belinda/Providence) eastbound; Belinda Pky./Providence Way not signed westbound | |

| 231.67 | 372.84 | 229 | Beckwith Road, Golden Bear Gateway | Signed as exits 229A (south) and 229B (north) eastbound; Golden Bear Gtwy. not signed eastbound | ||

| Lebanon | 234.49 | 377.38 | 232 | Signed as exits 232A (south) and 232B (north) eastbound | ||

| 237.56 | 382.32 | 235 | Eastern terminus and exits 76A-B on I-840; former SR 840; trumpet interchange | |||

| 239.03 | 384.68 | 236 | S. Hartmann Drive | Opened on October 18, 2002[294] | ||

| 240.54 | 387.11 | 238 | ||||

| 242.25 | 389.86 | 239 | Signed as exits 239A (east) and 239B (west) eastbound | |||

| Tuckers Crossroads | 247.43 | 398.20 | 245 | Linwood Road | ||

| Smith | New Middleton | 256.86 | 413.38 | 254 | ||

| Gordonsville | 261.06 | 420.14 | 258 | |||

| Caney Fork River | 265.68– 269.95 | 427.57– 434.44 | Five total crossings on five separate bridges | |||

| Putnam | Buffalo Valley | 270.78 | 435.78 | 268 | ||

| Silver Point | 275.88 | 443.99 | 273 | Western end of SR 56 overlap; eastbound exit ramp includes direct access to SR 141 west | ||

| Boma | 278.53 | 448.25 | 276 | Old Baxter Road | ||

| Baxter | 282.54 | 454.70 | 280 | Eastern end of SR 56 overlap | ||

| Cookeville | 285.33 | 459.19 | 283 | Tennessee Avenue, Highland Park Boulevard | Opened on June 20, 2018[295] | |

| 288.27 | 463.93 | 286 | ||||

| 289.77 | 466.34 | 287 | ||||

| 291.08 | 468.45 | 288 | ||||

| 292.72 | 471.09 | 290 | ||||

| Monterey | 303.62 | 488.63 | 300 | |||

| 304.27 | 489.68 | 301 | ||||

| Cumberland | | 313.44 | 504.43 | 311 | Plateau Road | |

| Crossville | 320.26 | 515.41 | 317 | |||

| 322.42 | 518.88 | 320 | ||||

| 324.66 | 522.49 | 322 | ||||

| Crab Orchard | 332.00 | 534.30 | 329 | |||

| | 341.13 | 549.00 | 338 | Western end of SR 299 overlap | ||

| Cumberland–Roane county line | | 343.16 | 552.26 | 340 | Eastern end of SR 299 overlap; transition from Central Time Zone to Eastern Time Zone | |

| Roane | Harriman | 350.34 | 563.82 | 347 | ||

| 353.05 | 568.18 | 350 | ||||

| Clinch River | 354.27– 354.54 | 570.14– 570.58 | Sam Rayburn Memorial Bridge | |||

| Kingston | 355.40 | 571.96 | 352 | Western end of SR 58 overlap | ||

| 358.25 | 576.55 | 355 | Lawnville Road | |||

| 359.31 | 578.25 | 356 | Eastern end of SR 58 overlap; signed as exits 356A (north) and 356B (south) westbound | |||

| | 363.09 | 584.34 | 360 | Buttermilk Road | ||

| | 364.09 | 585.95 | 362 | Industrial Park Road – Roane Regional Business and Technology Park | Opened on October 8, 2008.[296] | |

| Loudon | Lenoir City | 366.65 | 590.07 | 364 | ||

| | 370.22– 370.89 | 595.81– 596.89 | 368 | Western end of I-75 overlap; left exit and entrance westbound; I-75 exits 84A-B northbound; directional-T interchange | ||

| Knox | | 371.87 | 598.47 | 369 | Watt Road | |

| Farragut | 375.67 | 604.58 | 373 | Campbell Station Road – Farragut | ||

| Knoxville | 377.46 | 607.46 | 374 | |||

| 378.31– 379.62 | 608.83– 610.94 | 376 | Signed as exits 376A (north) and 376B (east); I-140 exits 1C-D westbound, not signed eastbound; cloverstack interchange | |||

| 380.68 | 612.65 | 378 | Cedar Bluff Road | Signed as exits 378A (south) and 378B (north) westbound | ||

| 381.95– 382.16 | 614.69– 615.03 | 379 | Bridgewater Road, Walker Springs Road | |||

| 382.55 | 615.65 | 379A | Gallaher View Road | Eastbound access is via exit 379 | ||

| 383.51 | 617.20 | 380 | ||||

| 385.54– 386.05 | 620.47– 621.29 | 383 | Complete access to Papermill Road; westbound exit and entrance only for Weisgarber Road; eastbound exit and entrance only for SR 332 (Northshore Drive); westbound entrance and exit ramps accessible via collector-distributor slip ramp | |||

| 387.64– 388.35 | 623.85– 624.99 | 385 | Eastern end of I-75 overlap; semi-directional T interchange | |||

| 389.20 | 626.36 | 386A | University Avenue, Middlebrook Pike | Westbound access is part of exit 386B; unsigned access to SR 169 | ||

| 389.20– 389.91 | 626.36– 627.50 | 386B | Semi-directional T interchange | |||

| 390.10– 390.33 | 627.81– 628.18 | 387 | Westbound access via Ailor Avenue | |||

| 390.20– 390.82 | 627.97– 628.96 | 387A | I-275 exit 0; former I-75 north; three-level stack interchange | |||

| 390.59 | 628.59 | 388 | Eastbound entrance only, access to SR 62 (Western Avenue) and Summit Hill Drive unsigned on I-40 | |||

| 390.92– 391.19 | 629.12– 629.56 | Broadway, Gay Street, Magnolia Avenue | Removed during reconstruction from 1980–1982[222] | |||

| 391.39 | 629.88 | 388A | Western end of SR 158 overlap (unsigned); semi-directional T interchange | |||

| 391.82 | 630.57 | 389 | SR 71 is unsigned | |||

| 393.00 | 632.47 | 390 | Cherry Street | |||

| 394.78 | 635.34 | 392 | Signed as exits 392A (south) and 392B (north) | |||

| 395.22– 395.98 | 636.04– 637.27 | 393 | I-640 exit 10; western end of US 25W/SR 9 overlap; semi-directional T interchange | |||

| 396.73 | 638.48 | 394 | Eastern end of US 25W/SR 9 overlap | |||

| Holston River | 397.55– 397.78 | 639.79– 640.16 | Ralph K. Adcock Memorial Bridge | |||

| | 400.67 | 644.82 | 398 | Strawberry Plains Pike – Strawberry Plains | ||

| | 405.05 | 651.86 | 402 | Midway Road – Seven Islands State Birding Park | ||

| Sevier | Sevierville | 410.31 | 660.33 | 407 | Western end of SR 66 overlap; reconstructed into a diverging diamond interchange (first in Tennessee) in 2015[297] | |

| | 408 | To serve a proposed connector road between SR 139 and Dumplin Valley Road[298] | ||||

| Jefferson | | 415.24 | 668.26 | 412 | Deep Springs Road – Douglas Dam | |

| | 418.42 | 673.38 | 415 | Eastern end of SR 66 overlap | ||

| Dandridge | 420.77 | 677.16 | 417 | |||

| | 424.01– 424.69 | 682.38– 683.47 | 421 | Left exit and entrance eastbound; southern terminus of I-81; I-81 exits 1A-B southbound; directional-T interchange | ||

| | 427.35 | 687.75 | 424 | |||

| French Broad River | 427.57– 428.04 | 688.11– 688.86 | Frances Burnett Swann Memorial Bridge | |||

| Cocke | Newport | 434.49 | 699.24 | 432 | Signed as exits 432A (south) and 432B (east) westbound; formerly exits 432A (south) and 432B (east) eastbound | |

| 438.23 | 705.26 | 435 | Currently a temporarily incomplete interchange with only eastbound exit and westbound entrance due to eastbound closure from damage by Hurricane Helene[299] | |||

| Wilton Springs | 443.27 | 713.37 | 440 | Temporarily closed due to severe damage from Hurricane Helene[299] | ||

| | 446.14 | 717.99 | 443 | Foothills Parkway – Gatlinburg, Cosby, Great Smoky Mountains National Park | Temporarily closed due to severe damage from Hurricane Helene[299] | |

| Hartford | 450.14 | 724.43 | 447 | Hartford Road | Temporarily closed due to severe damage from Hurricane Helene[299] | |

| | 453.73 | 730.21 | 451 | Waterville Road | Temporarily closed due to severe damage from Hurricane Helene[299] | |

| | 454.65 | 731.69 | Continuation into North Carolina; temporarily closed due to severe damage from Hurricane Helene[299] | |||

1.000 mi = 1.609 km; 1.000 km = 0.621 mi

| ||||||

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ While the stretch of I-40 in Tennessee is officially 455.28 miles (732.70 km) long, mileposts and exits remain numbered according to the original planned routing through Overton Park in Memphis, which was approximately 3.5 miles (5.6 km) shorter.[11]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Starks, Edward (January 27, 2022). "Table 1: Main Routes of the Dwight D. Eisenhower National System of Interstate and Defense Highways". FHWA Route Log and Finder List. Federal Highway Administration. Archived from the original on July 3, 2017. Retrieved February 23, 2023.

- ^ a b c Public Roads Administration (August 14, 1957). Official Route Numbering for the National System of Interstate and Defense Highways as Adopted by the American Association of State Highway Officials (Map). Washington, DC: Public Roads Administration. Archived from the original on July 19, 2017. Retrieved June 14, 2018 – via Wikimedia Commons.

- ^ a b "I-40 Link Opening Near Knoxville". The Tennessean. Nashville. Associated Press. September 11, 1975. p. 11. Archived from the original on April 19, 2022. Retrieved April 18, 2019.