Iridium(IV) oxide

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Other names

Iridium dioxide

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.031.572 |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| IrO2 | |

| Molar mass | 224.22 g/mol |

| Appearance | blue-black solid |

| Density | 11.66 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 1,100 °C (2,010 °F; 1,370 K) decomposes |

| insoluble | |

| +224.0·10−6 cm3/mol | |

| Structure | |

| Rutile (tetragonal) | |

| Octahedral (Ir); Trigonal (O) | |

| Hazards | |

| Flash point | Non-flammable |

| Related compounds | |

Other anions

|

iridium(IV) fluoride, iridium disulfide |

Other cations

|

rhodium dioxide, osmium dioxide, platinum dioxide |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Iridium(IV) oxide, IrO2, is the only well-characterised oxide of iridium. It is a blue-black solid, used with other rare oxides to coat anodes.

Synthesis

[edit]As described by its discoverers, it can be formed by treating the green form of iridium trichloride with oxygen at high temperatures:

- 2 IrCl3 + 2 O2 → 2 IrO2 + 3 Cl2

A hydrated form is also known.[1]

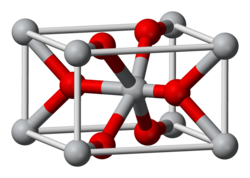

Structure

[edit]The compound adopts the TiO2 rutile structure, featuring six coordinate iridium and three coordinate oxygen.[2] It forms a tetragonal lattice with lattice parameters of 4.5Å and 3.15Å.[3]

Mechanical properties

[edit]Oxide materials are typically hard and brittle.[4] Indeed, iridium oxide does not easily deform under stress,[5] instead cracking easily.[6] Measured deflections of a thin, cantilevered iridium oxide film indicate a Young’s modulus of 300 ± 15 GPa,[5] substantially lower than the Young's modulus of metallic iridium (517 GPa).[7]

Applications

[edit]Iridium dioxide can be used to make coated electrodes[8] for industrial electrolysis or as microelectrodes for electrophysiology.[9] In electrolytic applications, IrO2 films evolve O2 efficiently.[10]

Electrode manufacture typically requires high-temperature annealing.[11]

Fracture and delamination are well-known problems when fabricating devices that incorporate iridium oxide film. One cause of delamination is lattice mismatch between iridium oxide and the substrate. Sputtering iridium oxide on a liquid crystal polymer has been proposed to avoid mismatch,[12] but sputtered films spontaneously delaminate during cyclic voltammetry if the maximum potential bias exceeds 0.9 V.[13]

References

[edit]- ^ H. L. Grube (1963). "The Platinum Metals". In G. Brauer (ed.). Handbook of Preparative Inorganic Chemistry, 2nd Ed. NY: Academic Press. p. 1590.

- ^ Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- ^ Bestaoui, N.; Prouzet, E.; Deniard, P.; Brec, R. (1993). "Structural and analytical characterization of an iridium oxide thin layer". Thin Solid Films. 235 (1–2): 35–42. Bibcode:1993TSF...235...35B. doi:10.1016/0040-6090(93)90239-l. ISSN 0040-6090.

- ^ Dillingham, Giles; Roberts, Rose (2023). Advances in Structural Adhesive Bonding (Second Edition) (2nd ed.). Woodhead Publishing. pp. 289–325. ISBN 9780323984379.

- ^ a b Rivas, Manuel; Rudy, Ryan Q.; Sanchez, Bradley; Graziano, Milena B.; Fox, Glen R.; Sunal, Paul; Nataraj, Latha; Sandoz-Rosado, Emil; Leff, Asher C.; Huey, Bryan D.; Polcawich, Ronald G.; Hanrahan, Brendan (2020-08-01). "Iridium oxide top electrodes for piezo- and pyroelectric performance enhancements in lead zirconate titanate thin-film devices". Journal of Materials Science. 55 (24): 10351–10363. Bibcode:2020JMatS..5510351R. doi:10.1007/s10853-020-04766-5. ISSN 1573-4803.

- ^ Mailley, S.C; Hyland, M; Mailley, P; McLaughlin, J.M; McAdams, E.T (2002). "Electrochemical and structural characterizations of electrodeposited iridium oxide thin-film electrodes applied to neurostimulating electrical signal". Materials Science and Engineering: C. 21 (1–2): 167–175. doi:10.1016/s0928-4931(02)00098-x. ISSN 0928-4931.

- ^ "Young's Modulus, Tensile Strength and Yield Strength Values for some Materials". www.engineeringtoolbox.com. Retrieved 2024-05-12.

- ^ "改性二氧化铱电极研制--《无机盐工业》1998年03期". www.cnki.com.cn. Retrieved 2021-05-21.

- ^ Cogan, Stuart F. (August 2008). "Neural Stimulation and Recording Electrodes". Annual Review of Biomedical Engineering. 10 (1): 275–309. doi:10.1146/annurev.bioeng.10.061807.160518. ISSN 1523-9829. PMID 18429704.

- ^ Wendt, Hartmut; Kolb, Dieter M.; Engelmann, Gerald E.; Ziegler, Jörg C. (15 Oct 2011). "Electrochemistry, 1: Fundamentals". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a09_183.pub4. ISBN 978-3-527-30673-2.

- ^ Dong, Qiuchen; Song, Donghui; Huang, Yikun; Xu, Zhiheng; Chapman, James H.; Willis, William S.; Li, Baikun; Lei, Yu (2018). "High-temperature annealing enabled iridium oxide nanofibers for both non-enzymatic glucose and solid-state pH sensing". Electrochimica Acta. 281: 117–126. doi:10.1016/j.electacta.2018.04.205. ISSN 0013-4686.

- ^ Wang, K.; Chung-Chiun Liu; Durand, D.M. (2009). "Flexible Nerve Stimulation Electrode With Iridium Oxide Sputtered on Liquid Crystal Polymer". IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering. 56 (1): 6–14. doi:10.1109/TBME.2008.926691. ISSN 0018-9294. PMC 2738844. PMID 19224713.

- ^ Cogan, Stuart F.; Ehrlich, Julia; Plante, Timothy D.; Smirnov, Anton; Shire, Douglas B.; Gingerich, Marcus; Rizzo, Joseph F. (2009). "Sputtered iridium oxide films for neural stimulation electrodes". Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part B: Applied Biomaterials. 89B (2): 353–361. doi:10.1002/jbm.b.31223. ISSN 1552-4973. PMC 7442142. PMID 18837458.