Eleven-plus

| Purpose | Determining admission to selective secondary schools |

|---|---|

| Year started | 1944 |

| Offered | To Year Six/Year 6 Primary, Seven/Primary 7 school pupils |

| Restrictions on attempts | Single attempt |

| Regions | England and Northern Ireland |

| Fee | Free (England)[citation needed] £50 administration fee (Northern Ireland)[1] |

| Used by | Selective secondary schools |

The eleven-plus (11+) is a standardised examination administered to some students in England and Northern Ireland in their last year of primary education, which governs admission to grammar schools and other secondary schools which use academic selection. The name derives from the age group for secondary entry: 11–12 years.

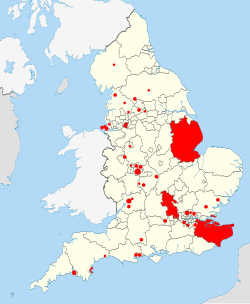

The eleven-plus was once used throughout the UK, but is now only used in counties and boroughs in England that offer selective schools instead of comprehensive schools.[2] Also known as the transfer test, it is especially associated with the Tripartite System which was in use from 1944 until it was phased out across most of the UK by 1976.[3]

The examination tests a student's ability to solve problems using a test of verbal reasoning and non-verbal reasoning, and most tests now also offer papers in mathematics and English. The intention was that the eleven-plus should be a general test for intelligence (cognitive ability) similar to an IQ test, but by also testing for taught curriculum skills it is evaluating academic ability developed over previous years, which implicitly indicates how supportive home and school environments have been.[citation needed]

Introduced in 1944, the examination was used to determine which type of school the student should attend after primary education: a grammar school, a secondary modern school, or a technical school. The base of the Tripartite System was the idea that skills were more important than financial resources in determining what kind of schooling a child should receive: different skills required different schooling.

In some local education authorities the Thorne plan or scheme or system developed by Alec Clegg, named in reference to Thorne Grammar School, which took account of primary school assessment as well as the once-off 11+ examination, was later introduced.[4][5]

Within the Tripartite System

[edit]The Tripartite System of education, with an academic, a technical and a functional strand, was established in the 1940s. Prevailing educational thought at the time was that testing was an effective way to discover the strand to which a child was most suited. The results of the exam would be used to match children's secondary schools to their abilities and future career needs.

When the system was implemented, technical schools were not available on the scale envisaged. Instead, the Tripartite System came to be characterised by fierce competition for places at the prestigious grammar schools. As such, the eleven-plus took on a particular significance. Rather than allocating according to need or ability, it became seen as a question of passing or failing. This led to the exam becoming widely resented by some although strongly supported by others.[6]

Structure

[edit]The structure of the eleven-plus varied over time, and among the different counties which used it. Usually, it consisted of three papers:

- Arithmetic – A mental arithmetic test.

- Writing – An essay question on a general subject.

- General Problem Solving – A test of general knowledge, assessing the ability to apply logic to simple problems.

Some exams have:

- Verbal Reasoning

- Non-Verbal Reasoning

Most children took the eleven-plus in their final year of primary school: usually at age 10 or 11. In Berkshire and Buckinghamshire it was also possible to sit the test a year early – a process named the ten-plus; later, the Buckinghamshire test was called the twelve-plus and taken a year later than usual.

Originally, the test was voluntary; as of 2009[update], some 30% of students in Northern Ireland do not sit for it.[7]

In Northern Ireland, pupils sitting the exam were awarded grades in the following ratios: A (25%), B1 (5%), B2 (5%), C1 (5%), C2 (5%), D (55%). There was no official distinction between pass grades and fail grades.

Current practice

[edit]

There are 163 remaining grammar schools in various parts of England, and 67 in Northern Ireland. In counties in which vestiges of the Tripartite System still survive, the eleven-plus continues to exist. Today it is generally used as an entrance test to a specific group of schools, rather than a blanket exam for all pupils, and is taken voluntarily. For more information on these, see the main article on grammar schools.

Eleven-plus and similar exams vary around the country but will use some or all of the following components:

- Verbal Reasoning (VR)

- Non-Verbal reasoning (NVR)

- Mathematics (MA)

- English (EN)

Eleven-plus tests take place in September of children's final primary school year with results provided to parents in October to allow application for secondary schools. In Lincolnshire children will sit the Verbal Reasoning and Non-Verbal Reasoning. In Buckinghamshire children sit tests in Verbal Reasoning, Mathematics and Non-Verbal reasoning. In Kent, where the eleven-plus test is more commonly known as the Kent Test, children sit all four of the above disciplines; however the Creative Writing, which falls as part the English test, will only be used in circumstances of appeal.[9] In the London Borough of Bexley from September 2008, following a public consultation, pupils sitting the Eleven-Plus exam are only required to do a Mathematics and Verbal Reasoning paper. In Essex, where the examination is optional, children sit Verbal Reasoning, Mathematics and English. Other areas use different combinations. Some authorities/areas operate an opt-in system, while others (such as Buckinghamshire) operate an opt-out system where all pupils are entered unless parents decide to opt out. In the North Yorkshire, Harrogate/York area, children are only required to sit two tests: Verbal and Non-Verbal Reasoning.

Independent schools in England generally select children at the age of 13, using a common set of papers known as the Common Entrance Examination.[10] About ten do select at eleven; using papers in English, Mathematics and Science. These also have the Common entrance exam name.[11]

Scoring

[edit]This section possibly contains original research. (April 2023) |

| Authority/consortium | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|

| Bishop Wordsworth | 100 | 15 |

| Chelmsford | 100 | 15 |

| Dover Grammar School for Boys | 100 | 15 |

| Folkestone | 100 | 15 |

| Gloucester | 100 | 15 |

| Harvey | 100 | 15 |

| Heckmondwike | 100 | 15 |

| Henrietta Barnett School | 100 | 15 |

| Kendrick School | 100 | 15 |

| Mayfield | 100 | 15 |

| Reading School | 100 | 15 |

| Redbridge | 100 | 15 |

| The Latymer School | 100 | 15 |

| Torbay and Devon Consortium | 100 | 15 |

| West Midland Boys | 100 | 15 |

| West Midland Girls | 100 | 15 |

| Buckinghamshire | 100 | 43 |

| Dame Alice Owen | 106 | 15 |

| Slough Consortium | 106 | 15 |

| South West Herts | 106 | 15 |

| Bexley | 200 | 30 |

| King Edwards Consortium | 200 | 30 |

| Warwickshire | 200 | 30 |

| Wirral Borough Council | 234 | 15 |

| Altrincham | 315 | 30 |

| Sale | 318 | 30 |

| Stretford | 327 | 30 |

| Urmston | 328 | 30 |

England has 163 grammar schools 155 of which control their own admissions including the choice of test. (143 Academy Converters, six Foundation schools and six Voluntary aided schools control their own admissions. Admissions for the remaining seven Community Schools and one Voluntary Controlled school are determined by the local authority.; [12] [13]

Over 95% of grammar schools now determine their own admissions policies, choosing what tests to set and how to weight each component. Although some form consortia with nearby schools to agree on a common test, there may be as many as 70 different 11+ tests set across the country [14] meaning it is not possible to refer to the eleven plus test as a single entity.

Tests are multiple choice. The number of questions varies but the guidance provided by GLA [15] shows that full length Maths and English Comprehension tests are both 50 minutes duration and consist of about 50 questions. Verbal Reasoning is 60 minutes containing 80 questions. Non-Verbal Reasoning is 40 minutes broken into four 10-minute separately-timed sections each containing 20 questions. At a rate of one question every 30 seconds, it could be argued that the test is one of speed rather than intelligence.

One mark is awarded for each correct answer. No marks are deducted for incorrect or un-attempted responses. [16] There are usually five possible answers, one of which is always correct meaning a random guess has a 20% chance of being correct and a strategy of guessing all un-attempted questions in the last few seconds of the exam will, if anything, gain the candidate a few additional marks which may make the difference needed to gain a place.

The actual marks from these tests, referred to as raw marks, are not disclosed by all schools, and instead parents are given Standard Age Scores (SAS). A standard score shows how well the individual has performed relative to the mean (average) score for the population although the term population is open to interpretation. GL Assessment, who set the majority of 11+ tests, say it should be, "a very large, representative sample of students usually across the UK";[17] however, grammar schools may standardise their tests against just those children who apply to them in a given year, as this enables them to match supply to demand.

Test results follow a normal distribution resulting in the familiar bell curve which reliably predicts how many test takers gain each different score. For example, only 15.866% score more than one standard deviation above the mean (+1σ generally represented as 115 SAS) as can be seen by adding up the proportions in this graph based on the original provided by M. W. Toews).

By standardising on just the cohort of applicants, a school with for example, 100 places which regularly gets 800 applications can set a minimum pass mark of 115 which selects approximately 127 applicants filling all of the places and leaving about 27 on the waiting list. The downside of this local standardisation, as it has been called, is parents are frequently unaware that their children are being judged as much by the standard of other applicants as their own abilities.

Another issue with the lack of national standards in testing is it prevents any comparison between schools. Public perception may be that only pupils who are of grammar school standard are admitted to grammar schools; however, other information such as the DfE league tables[18][19] calls into question the existence of any such standard. Competition for places at Sutton Grammar School is extremely fierce with, according to an online forum[20] over 2,500 applicants in 2016. At the other end of the scale, Buckinghamshire council website says, "If your child's STTS is 121 or above, they qualify for grammar school. We expect that about 37% of children will get an STTS of 121 or more."[21] Official statistics show 100% of those admitted to Sutton Grammar School have, "high prior attainment at the end of key stage 2", compared to only 44% of those who attend Skegness Grammar School. The Grammar Schools Heads Association's Spring 2017 newsletter[22][23] says the government are considering a national selection test which would remove the lack of consistency between different 11+ tests.

Between them, GL (Granada Learning) and CEM (Centre for Evaluation and Monitoring) earn an estimated £2.5m annually[24] from setting and marking the 11+ tests. Releasing the raw marks would bring some clarity to the admissions process but attempts to do so have generally been unsuccessful. GL have used the fact that they are not covered by Freedom of Information legislation to withhold information[25] made for information relating to the 11+ exams used by Altrincham Grammar School for Boys, who stated, "Our examination provider, GL Assessment Limited (GL) is not subject to the Freedom of Information Act 2000 (FOI) as it is not a public body.“, whilst their main rival CEM successfully argued in court[26][27] that, "one of the benefits of its 11+ testing is that it is 'tutor proof'” and releasing the raw marks would undermine this unique selling point.

When a standard score is calculated the results is a negative value for any values below the mean. As it would seem very strange to be given a negative score Goldstein and Fogelman (1974)[28] explain, "It is common to 'normalise' the scores by transforming them to give a distribution with a mean of 100 and a standard deviation of 15."[29] Thus a normalised SAS of 100 indicates the mean (average) achievement whilst a score of 130 would be two standard deviations above the mean. A score achieved by only 2.2% of the population. Most, but not all, authorities normalise follow this convention. The following table[30] showing the normalisation values used by some for 2017 entry (tests taken in 2016).

Northern Ireland

[edit]The system in Northern Ireland differed from that in England. The last eleven-plus was held in November 2008.[31] A provision in the Education Order (NI) 1997 states that "the Department may issue and revise guidance as it thinks appropriate for admission of pupils to grant-aided schools". Citing this on 21 January 2008, Northern Ireland's Education Minister Caitríona Ruane passed new guidelines regarding post-primary progression as regulation rather than as legislation. This avoided the need for the proposals to be passed by the Northern Ireland Assembly, where cross-party support for the changes did not exist.[32][33] Some schools, parents and political parties object to the new legal framework. As a result, many post-primary schools are setting their own entrance examinations.

Controversy

[edit]

The 11-plus was a result of major changes which took place in English and Welsh education in the years up to 1944. In particular, the Hadow Report of 1926 called for the division of primary and secondary education to take place on the cusp of adolescence at 11 or 12. The implementation of this break by the Butler Act seemed to offer an ideal opportunity to implement streaming, since all children would be changing school anyway. Thus testing at 11 emerged largely as an historical accident, without other specific reasons for testing at that age.

The test, composed of Maths, English and Verbal Reasoning could not be passed by 10-year-olds who had not been trained for the test.[according to whom?] Martin Stephen a former High Master of Manchester Grammar School asserted on BBC Radio 4's The Moral Maze that no child who had not seen the verbal reasoning tests that formed the basis of the 11-plus before attempting them would have a "hope in hell" of passing them, and he had dispensed with the 11-plus as "worthless". Instead he used personal interviews.[34] Children in school were drilled in the 11-plus until it was "coming out of their ears".[citation needed] Families had to play the system, little booklets were available from local newsagents that showed how to pass the exam and contained many past papers with all the answers provided, which the children then learned by rote.[34]

Criticism of the 11-plus arose on a number of grounds, though many related more to the wider education system than to academic selection generally or the 11-plus specifically. The proportions of schoolchildren gaining a place at a grammar school varied by location and sex. 35% of pupils in the South West of England secured grammar school places as opposed to 10% in Nottinghamshire.[35] In some areas, because of the continuance of single-sex schooling in those areas, there were sometimes fewer places for girls than for boys. Some areas were coeducational and had equal number of places for each sex.

Critics of the 11-plus also claimed that there was a strong class bias in the exam. JWB Douglas, studying the question in 1957, found that children on the borderline of passing were more likely to get grammar school places if they came from middle-class families.[36] For example, questions about the role of household servants or classical composers were far easier for middle-class children to answer than for those from less wealthy or less educated backgrounds.[citation needed] In response, the 11-plus was redesigned during the 1960s to be more like an IQ test. However, even after this modification, grammar schools were largely attended by middle-class children while secondary modern schools were attended by mostly working-class children.[37][38][39] By testing cognitive skills the child's innate ability is evaluated as a predictor to future academic performance and is largely independent of background and support [citation needed]. The problem lies with the testing of academic subjects, such as Maths and English, where a child from a working class background with a less supportive school and less educated parents is being measured on their learning environment instead of potential to succeed [citation needed].

Passing – or not passing – the 11-plus was a "defining moment in many lives", with education viewed as "the silver bullet for enhanced social mobility."[40] Richard Hoggart claimed in 1961 that "what happens in thousands of homes is that the 11-plus examination is identified in the minds of parents, not with 'our Jimmy is a clever lad and he's going to have his talents trained', but 'our Jimmy is going to move into another class, he's going to get a white-collar job' or something like that."[41]

References

[edit]- ^ https://seagni.co.uk/

- ^ Adams, Richard (6 September 2024). "English grammar schools raising funds with charge for mock 11-plus exam". The Guardian.

- ^ Moonsammy, Ashminnie (7 May 2025). "Education officials fan out for 11-Plus exams". nationnews.com.

- ^ Wainwright, Martin (7 December 1999). "The great grammar divide". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 November 2024.

- ^ "Medway: Parents raise concerns over this year's 11-plus exam". www.bbc.com. 19 September 2024.

- ^ Fletcher, Tony (1998). Dear Boy: The Life of Keith Moon. Omnibus Press. pp. 9, 11. ISBN 978-1-84449-807-9.

- ^ "Transfer Procedure – Department of Education, Northern Ireland". Deni.gov.uk. Retrieved 17 October 2009.

- ^ The Education (Grammar School Ballots) Regulations 1998, Statutory Instrument 1998 No. 2876, UK Parliament.

- ^ "Kent Test Guidance". How2Become.

- ^ "Common Entrance at 13+". www.iseb.co.uk. Retrieved 9 June 2018.

- ^ "Common Entrance at 11+". www.iseb.co.uk. Retrieved 9 June 2018.

- ^ DfE Schools Pupils and Characteristics datasetSchool level data. Department for Education.

- ^ West, Anne and David Wolfe. Academies, autonomy, equality and democratic accountability: Reforming the fragmented publicly funded school system in England. London Review of Education (2019)

- ^ CEM set tests for 28 different LAs, consortia and individual schools and claim to have 40% of the market. Extrapolating would suggest there are approx. 70 different sets of tests in total.

- ^ Free familiarisation materials[1]. Granada Learning Assessment (GLA).

- ^ Freedom of Information[2]. Buckinghamshire Grammar Schools.

- ^ GL Assessment A short guide to standardised tests. 013 GL Assessment Limited.

- ^ "Download data – GOV.UK – Find and compare schools in England". Find and compare schools in England.

- ^ Data source: England_ks4final.csv. Field 39, PTPRIORHI shows the Percentage of pupils at the end of key stage 4 with high prior attainment at the end of key stage 2.

- ^ "11 plus Surrey, Grammar School Admissions". www.elevenplusexams.co.uk.

- ^ Marking the Secondary Transfer Test[3]. Buckinghamshire Council.

- ^ "GSHA Newsletter" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 October 2018.

- ^ "The Grammar Schools Heads Association's website went offline in early July 2017 but a copy of their Spring newsletter is still available from Schools Week's website" (PDF).

- ^ Coombs v Information Commissioner, EA/2015/0226, 22 April 2016, p. 11. CEM told the Information Commissioner they earn £1m from 40% of the market making £2.5m a reasonable estimate for 100% of the market.

- ^ "Request for report on 11+ exam – a Freedom of Information request to Altrincham Grammar School For Boys". 23 May 2016.

- ^ "Case no. EA/2015/0226" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 May 2020.

- ^ Coombs v Information Commissioner (ibid), p. 5.

- ^ "Age standardisation and seasonal effects in mental testing" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 May 2015.

- ^ "Goldstein H and Fogelman K, 1974, Age standardisation and seasonal effects in mental testing. Downloaded from /www.bristol.ac.uk" (PDF).

- ^ "CEM 11+ test results 2014 – 2016. – a Freedom of Information request to Durham University". 6 October 2016.

- ^ "Future uncertain as 11-plus ends". BBC News Online. 21 November 2008. Retrieved 27 June 2009.

- ^ Anne Murray (3 February 2009). "Ruane urged to publish legal advice on transfer plans – Education, News". Belfasttelegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 17 October 2009.

- ^ "The tricky path from peace to harmony". Public Service. 21 January 2008. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 17 October 2009.

- ^ a b Horrie, Chris (4 May 2017). "Grammar schools: back to the bad old days of inequality". The Guardian. Retrieved 16 October 2018.

- ^ Szreter, S. Lecture, University of Cambridge, Lent Term 2004.

- ^ Sampson, A. Anatomy of Britain Today, London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1965, p. 195.

- ^ Hart, R.A., Moro M., Roberts J.E., 'Date of birth, family background, and the Eleven-Plus exam: short- and long-term consequences of the 1944 secondary education reforms in England and Wales', Stirling Economics Discussion Paper 2012-10 May 2012 pp. 6 to 25. "Working Papers". Archived from the original on 5 July 2011. Retrieved 19 February 2013.

- ^ "Reflecting Education". reflectingeducation.net.

- ^ Sampson, A., Anatomy of Britain Today, Hodder and Stoughton, 1965, pp. 194–195.

- ^ David Kynaston, Modernity Britain: A Shake of the Dice 1959–62, Bloomsbury, 2014, pp.179–182.

- ^ Kynaston, p. 192.

External links

[edit]- Taylor, Matthew (28 July 2005). "PAT, dissenting teaching union, calls for return of 11-plus". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 October 2009.

- Beckett, Francis (15 October 2002). "Not so special after all". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 October 2009.

- Baker, Mike (15 February 2003). "What future for grammar schools?". BBC News. Retrieved 17 October 2009.

- "School admissions 'socially divisive'". BBC News. 31 January 2003. Retrieved 17 October 2009.

- "State schools 'failing brightest pupils'". The Guardian. 23 May 2005. Retrieved 17 October 2009.