Los Angeles Philharmonic

| Los Angeles Philharmonic | |

|---|---|

| Orchestra | |

Los Angeles Philharmonic concert at the Hollywood Bowl | |

| Short name | LA Phil |

| Founded | 1919 |

| Location | Los Angeles, United States |

| Concert hall | Walt Disney Concert Hall Hollywood Bowl |

| Music director | Gustavo Dudamel |

| Website | www |

The Los Angeles Philharmonic (LA Phil) is an American orchestra based in Los Angeles, California. The orchestra holds a regular concert season from October until June at the Walt Disney Concert Hall and a summer season at the Hollywood Bowl from July until September. Gustavo Dudamel is the current Musical Director, while Esa-Pekka Salonen serves as Conductor Laureate, Zubin Mehta as Conductor Emeritus, and Susanna Mälkki as Principal Guest Conductor. John Adams is the orchestra’s current Composer-in-Residence.

This orchestra has been received well among critics, with some stating it as "contemporary minded",[1] "forward thinking",[2] "talked about and innovative",[3] and "venturesome and admired".[4] "We are interested in the future", Conductor Salonen said, "We are not trying to re-create the glories of the past, like so many other symphony orchestras".[1]

The orchestra's former chief executive officer, Deborah Borda, said, "Our intention has been to integrate 21st-century music into the orchestra's everyday activity, especially since we moved into the new hall".[5]

Since the opening of the Walt Disney Concert Hall on October 23, 2003, the Los Angeles Philharmonic has presented 57 world premieres, one North American premiere, and 26 U.S. premieres, and has commissioned or co-commissioned 63 new works.

History

[edit]1919–1933: Founding the Philharmonic

[edit]

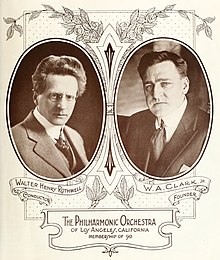

The orchestra was founded and single-handedly financed in 1919 by William Andrews Clark, Jr., a copper baron, arts enthusiast, and part-time violinist. He originally asked Sergei Rachmaninoff to be the Philharmonic's first music director; however, Rachmaninoff had only recently moved to New York, and he did not wish to move again. Clark then selected Walter Henry Rothwell, former assistant to Gustav Mahler, as music director, and hired away several principal musicians from East Coast orchestras and others from the competing and soon-to-be defunct Los Angeles Symphony. The orchestra played its first concert in the Trinity Auditorium in the same year,[6] eleven days after its first rehearsal. Clark himself would sometimes sit and play with the second violin section.[7]

After Rothwell's death in 1927, subsequent Music Directors in the decade of the 1920s included Georg Schnéevoigt and Artur Rodziński.

1933–1950: Harvey Mudd rescues orchestra

[edit]Otto Klemperer became Music Director in 1933, part of the large group of German emigrants fleeing Nazi Germany. He conducted many LA Phil premieres, and introduced Los Angeles audiences to new works by Igor Stravinsky and Arnold Schoenberg. The orchestra responded well to his leadership, but Klemperer had a difficult time adjusting to Southern California, a situation exacerbated by repeated manic-depressive episodes.

The situation grew more challenging when founder William Andrews Clark died without leaving the orchestra an endowment. The newly formed Southern California Symphony Association was created with the goal to stabilize the orchestra's funding, with the association's president, Harvey Mudd, stepping up to personally guarantee Klemperer's salary. The Philharmonic's concerts at the Hollywood Bowl also brought in much needed revenue.[7][8] As a result, the orchestra navigated the challenges of the Great Depression and remained intact.

After completing the 1939 summer season at the Hollywood Bowl, Klemperer visited Boston, where he was diagnosed with an acoustic neuroma. Brain surgery left him partially paralyzed in the face and with impaired hearing in his right ear. He went into a depressive state and was institutionalized. When he escaped, The New York Times ran a cover story declaring him missing. After he was found in New Jersey, a picture of him behind bars was printed in the New York Herald Tribune. He subsequently lost the post of Music Director, though he still would occasionally conduct the Philharmonic. He led some notable concerts, including the orchestra's premiere performance of Stravinsky's Symphony in Three Movements in 1946.[7][9]

John Barbirolli was offered the position of Music Director after his contract with the New York Philharmonic expired in 1942. He declined the offer and chose to return to England instead.[10] The following year, Alfred Wallenstein was chosen by Mudd to lead the orchestra. The former principal cellist of the New York Philharmonic, he had been the youngest member of the Los Angeles Philharmonic when it was founded in 1919. He turned to conducting at the suggestion of Arturo Toscanini. He had conducted the L.A. Philharmonic at the Hollywood Bowl on a number of occasions and, in 1943, took over as Music Director.[11] Among the highlights of Wallenstein's tenure were recordings of concertos with fellow Angelenos, Jascha Heifetz and Arthur Rubinstein.[7]

1951–1968: Dorothy Buffum Chandler's influence

[edit]By the mid-1950s, department store heiress and wife of the publisher of the Los Angeles Times, Dorothy Buffum Chandler became the de facto leader of the orchestra's board of directors. She led on efforts to create a performing arts center for the city, which would eventually become the Los Angeles Music Center and serve as the Philharmonic's new home. In addition, she and others sought a more prominent conductor to lead the orchestra. Following Wallenstein's departure, Chandler led efforts to hire Eduard van Beinum, then principal conductor of the Concertgebouw Orchestra, as the LAPO music director. The Philharmonic's musicians, management and audience all held Beinum in high regard, but in 1959, he suffered a fatal heart attack while on the podium during a rehearsal of the Concertgebouw Orchestra.[8]

In 1960, the orchestra, under Chandler's leadership, signed Georg Solti to a three-year contract as music director. This followed his guest conducting appearances in winter concerts downtown, at the Hollywood Bowl, and in other Southern California locations including CAMA concerts in Santa Barbara.[12] Solti was scheduled to officially begin his tenure in 1962, and the Philharmonic anticipated he would lead the orchestra when it moved into its new home at the then yet-to-be-completed Dorothy Chandler Pavilion. He had even began appointing musicians to the orchestra.[13] However, in 1961, Solti abruptly resigned the before officially taking the post after claiming that the Philharmonic board of directors did not consult him before naming then 26-year-old Zubin Mehta to be assistant conductor of the orchestra.[14] Mehta was subsequently named to replace Solti.

1969–1997: Ernest Fleischmann's tenure

[edit]In 1969, the orchestra hired Ernest Fleischmann to be Executive Vice President and General Manager. During his tenure, the Philharmonic instituted several ideas, including the creation of the Los Angeles Philharmonic Chamber Music Society and the Los Angeles Philharmonic New Music Group and its "Green Umbrella" concerts. These adjunct groups, composed of the orchestra's musicians, offered performance series separate and distinct from traditional Philharmonic concerts. These initiatives were later adopted by other orchestras worldwide. This concept, considered innovative for its time, stemmed from Fleischmann's philosophy, which he articulated in his May 16, 1987, commencement address at the Cleveland Institute of Music titled, "The Orchestra is Dead. Long Live the Community of Musicians."

When Zubin Mehta left for the New York Philharmonic in 1978, Fleischmann convinced Carlo Maria Giulini to take over as Music Director. Giulini's tenure with the orchestra was well regarded, but he resigned after his wife became ill and returned to Italy.

In 1985, Fleischmann turned to André Previn, hoping that his conducting credentials and experience at Hollywood Studios would bring a local flair and strengthen the connection between conductor, orchestra, and city. While Previn's tenure was musically solid, other conductors including Kurt Sanderling, Simon Rattle, and Esa-Pekka Salonen, achieved greater box office success. Previn frequently clashed with Fleischmann, notably over Fleischmann’s decision to name Salonen as "Principal Guest Conductor" without consulting Previn. This mirrored the earlier Solti/Mehta controversy. Due to Previn's objections, the offer of the position and an accompanying Japan tour to Salonen was withdrawn. Shortly after, in April 1989, Previn resigned, and four months later, Salonen was named Music Director Designate, officially assuming the post in October 1992.[15] Salonen's U.S. conducting debut with the orchestra had been in 1984.

Salonen's tenure began with a residency at the 1992 Salzburg Festival in concert performances and as the pit orchestra in a production of the opera Saint François d'Assise by Olivier Messiaen. This marked the first time an American orchestra was given that opportunity. Salonen later led the orchestra on numerous tours across the United States, Europe, and Asia, as well as residencies at the Lucerne Festival in Switzerland, The Proms in London, a festival in Cologne dedicated to Salonen's own works, and in 1996 at the Théâtre du Châtelet in Paris for a Stravinsky festival conducted by Salonen and Pierre Boulez. During the Paris residency, key Philharmonic board members heard the orchestra perform in improved acoustics, inspiring renewed fundraising efforts for the soon-to-be-built Walt Disney Concert Hall.

Under Salonen's leadership, the Philharmonic became known as a highly innovative and respected orchestra. Alex Ross of The New Yorker said:

The Salonen era in L.A. may mark a turning point in the recent history of classical music in America. It is a story not of an individual magically imprinting his personality on an institution—what Salonen has called the "empty hype" of conductor worship—but of an individual and an institution bringing out unforeseen capabilities in each other, and thereby proving how much life remains in the orchestra itself, at once the most conservative and the most powerful of musical organisms. ... no American orchestra matches the L.A. Philharmonic in its ability to assimilate a huge range of music on a moment's notice. [Thomas] Adès, who first conducted his own music in L.A. [in 2005] and has become an annual visitor, told me, "They always seem to begin by finding exactly the right playing style for each piece of music—the kind of sound, the kind of phrasing, breathing, attacks, colors, the indefinable whole. That shouldn't be unusual, but it is." John Adams calls the Philharmonic "the most Amurrican [sic] of orchestras. They don't hold back and they don't put on airs. If you met them in twos or threes, you'd have no idea they were playing in an orchestra, that they were classical-music people."[1]

1998–2009

[edit]When Fleischmann decided to retire in 1998 after 28 years at the helm, the orchestra named Willem Wijnbergen as its new Executive Director. Wijnbergen, a Dutch pianist and arts administrator, was the managing director of the Concertgebouw Orchestra in Amsterdam. Initially, his appointment was hailed as a major coup for the orchestra. One notable decision during his tenure was to revise Hollywood Bowl programming by increasing the number of jazz concerts and appointing John Clayton as the orchestra's first Jazz Chair. In addition, he established a new World Music series with Tom Schnabel as programming director.[16] Despite some successes, Wijnbergen departed the orchestra in 1999 after a year marked by controversy. It remains unclear whether he resigned or was dismissed by the Philharmonic's board of directors.[17]

Later that year, Deborah Borda, then Executive Director of the New York Philharmonic, was hired to lead the orchestra's executive management. She began her tenure in January 2000 and was later given the title of President and Chief Executive Officer. Following the financial challenges of Wijnbergen's brief tenure, Borda focused on stabilizing the organization's finances. Described as "a formidable executive who runs the orchestra like a lean company, not like a flabby non-profit," she is credited with putting the "organization on solid financial footing."[1] Borda is widely recognized, along with Salonen, Frank Gehry, and Yasuhisa Toyota, for the orchestra's successful transition to Walt Disney Concert Hall, and for supporting and complementing Salonen's artistic vision. One example cited by Alex Ross:

Perhaps Borda's boldest notion is to give visiting composers such as [John] Adams and Thomas Adès the same royal treatment that is extended to the likes of Yo-Yo Ma and Joshua Bell; Borda talks about "hero composers." A recent performance of Adams's monumental California symphony "Naïve and Sentimental Music" in the orchestra's Casual Fridays series ... drew a nearly full house. Borda's big-guns approach has invigorated the orchestra's long-running new-music series, called Green Umbrella, which Fleischmann established in 1982. In the early days, it drew modest audiences, but in recent years attendance has risen to the point where as many as sixteen hundred people show up for a concert that in other cities might draw thirty or forty. The Australian composer Brett Dean recently walked onstage for a Green Umbrella concert and did a double-take, saying that it was the largest new-music audience he'd ever seen.[1]

On July 13, 2005, Gustavo Dudamel made his debut with the LA Philharmonic at the orchestra's summer home, the Hollywood Bowl.[18] On January 4, 2007, Dudamel made his Walt Disney Concert Hall debut with the LA Philharmonic.[19] On April 9, 2007, the symphony board announced the departure of Esa-Pekka Salonen as music director at the end of the 2008–2009 season, and the appointment of Dudamel as Salonen's successor.[13][14][15] In 2007, two years before Dudamel's officially became music director, the LA Philharmonic established YOLA (Youth Orchestra Los Angeles). "The model for YOLA – a nonprofit initiative that supplies underprivileged children with free instruments, instruction, and profound lessons about pride, community, and commitment – is El Sistema, Venezuela's national music training program which, 27 years ago, nurtured the talents of a 5-year-old violin prodigy named Gustavo."[20] On May 11, 2009, shortly before the start of his inaugural season with the LA Philharmonic, Dudamel, was included as a finalist in Time's "The Time 100: The World's Most Influential People."[21]

2009–present

[edit]Dudamel began his official tenure as music director of the Los Angeles Philharmonic in 2009 with concerts at both the Hollywood Bowl (¡Bienvenido Gustavo!) on October 3, 2009[22] and the Inaugural Gala at Walt Disney Concert Hall on October 8, 2009.[23] In 2010 and 2011, Dudamel and the LA Phil received the Morton Gould Award for Innovative Programming by the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP),[13][24][25] and in 2012 Dudamel and the orchestra won the first place Award for Programming Contemporary Music by ASCAP.[26]

In 2012, Dudamel, the Los Angeles Philharmonic and the Simón Bolívar Symphony Orchestra of Venezuela performed all nine of Mahler's symphonies over three weeks in Los Angeles and one week in Caracas. The project was described as both "a mammoth tribute to the composer" and "an unprecedented conducting feat for the conductor."[27] That same year, the orchestra launched a three-year project to present the Mozart/Da Ponte operas, directed by Christopher Alden with each designed in collaboration with famous architects (sets) and clothing designers.[28] The series launched in 2012 with Frank Gehry and Rodarte designing Don Giovanni[28] and continued in 2013 with Jean Nouvel and Azzedine Alaïa designing Le Nozze di Figaro.[29] In 2014, the featured designers for the Così fan tutte production were Zaha Hadid and Hussein Chalayan.[30]

In October 2011, Dudamel was named Gramophone Artist of the Year.[31] In 2012, Dudamel and the LA Phil were awarded a Grammy award for Best Orchestral Performance for their recording of Brahms' Fourth Symphony.[32] Dudamel was also named Musical America's 2013 Musician of the Year.[33] In 2020 and 2021, Dudamel and the LA Phil were awarded consecutive Grammy awards for Best Orchestral Performance for their recordings of Andrew Norman's Sustain (2020),[34] and for the collected symphonies of Charles Ives (2021).[35] In 2024, Dudamel and the LA Phil won the Best Orchestral Performance Grammy award for a fourth time, with their performance of Adès: Dante (2020) by Thomas Adès.[36]

In February 2023, the orchestra announced that Dudamel is to conclude his tenure as its music director at the close of his current contract, at the end of the 2025–2026 season.[37] In May 2024, the orchestra announced the appointment of Kim Noltemy as its next president and chief executive officer, effective July 2024.[38][39]

Performance venues

[edit]

The orchestra played its first season at Trinity Auditorium at Grand Ave and Ninth Street. In 1920, it moved to Fifth Street and Olive Ave, in a venue that had previously been known as Clune's Auditorium, but was renamed Philharmonic Auditorium.[40] From 1964 to 2003, the orchestra played its main subscription concerts in the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion of the Los Angeles Music Center. In 2003, it moved to the new Walt Disney Concert Hall designed by Frank Gehry adjacent to the Chandler. Its current "winter season" runs from October through late May or early June.

Since 1922, the orchestra has played outdoor concerts during the summer at the Hollywood Bowl, with the official "summer season" running from July through September.

The LA Philharmonic has played at least one concert a year in its sister city, Santa Barbara, presented by the Community Arts Music Association (CAMA), along with other regular concerts throughout various Southern California cities such as Costa Mesa as part of the Orange County Philharmonic Society's series, San Diego, Palm Springs, among many others. In addition, the orchestra plays a number of free community concerts throughout Los Angeles County.

Conductors

[edit]Music Directors

[edit]- Walter Henry Rothwell (1919–1927)

- Georg Schnéevoigt (1927–1929)

- Artur Rodziński (1929–1933)

- Otto Klemperer (1933–1939)

- Alfred Wallenstein (1943–1956)

- Eduard van Beinum (1956–1959)

- Zubin Mehta (1962–1978)

- Carlo Maria Giulini (1978–1984)

- André Previn (1985–1989)

- Esa-Pekka Salonen (1992–2009)

- Gustavo Dudamel (2009–present)

Georg Solti accepted the post in 1960, but resigned in 1961 without officially beginning his tenure.[41]

Conductor Laureate

[edit]- 2009–present Esa-Pekka Salonen

Before Salonen's last concert as Music Director of the Los Angeles Philharmonic on April 19, 2009, the orchestra announced his appointment as its first ever Conductor Laureate "as acknowledgement of our profound gratitude to him and to signify our continuing connection."[42] In response, Salonen said:

When the Board asked me if I would accept the position of Conductor Laureate I was overwhelmed. This organization has been at the very center of my musical life for 17 years. I am very proud and honored that they would even consider me for such a prestigious title and it gives me great pleasure to accept. The Los Angeles Philharmonic will always play an important role in my life and this is a symbol of our continuing relationship.[42]

Conductor Emeritus

[edit]- 2019–present Zubin Mehta

During the intermission of a concert on January 3, 2019, Simon Woods, CEO of the orchestra, announced that Zubin Mehta has been awarded the title of Conductor Emeritus. Woods remarked on Mehta's contributions to the orchestra, noting: "Zubin Mehta is one of the treasures of the classical world. He was responsible for hiring over 80 musicians during his tenure at the LA Philharmonic, and it was during this remarkable era that the orchestra rose to a position of international prominence and launched a commitment to deep community engagement that was truly ahead of its time. Today's appointment is an acknowledgment of that incredible past and rich present, and a signal of our profound gratitude for the role he has played in shaping this orchestra."[43]

Mehta commented: "This is indeed a great honor and I'm very pleased to accept. The Los Angeles Philharmonic has always held a very special place in my heart; they took a chance and accepted me as a very young conductor. I remain grateful to the orchestra and I'm happy to continue our relationship in this way."[43]

Principal Guest Conductors

[edit]

|

Rattle and Tilson Thomas were named Principal Guest Conductor concurrently under Carlo Maria Giulini, though Tilson Thomas's tenure ended much earlier. Until 2016, they were the only two conductors to officially hold the title as such (though as stated above, Esa-Pekka Salonen was initially offered the position under Previn before having the offer withdrawn).

Beginning in the summer of 2005, the Philharmonic created the new position of Principal Guest Conductor of the Los Angeles Philharmonic at the Hollywood Bowl. Leonard Slatkin was initially given a two-year contract, and in 2007 he was given a one-year extension. In March 2008, Bramwell Tovey was named to the post for an initial two-year contract beginning Summer of 2008; he subsequently received a one-year extension. After Tovey's term ended, no conductor has since held the position at the Hollywood Bowl.[44][45]

In April 2016, the LA Phil announced Susanna Mälkki as the orchestra's next principal guest conductor, becoming first woman to hold the post. Her tenure began with the 2017–2018 season under an initial contract of three years.[46] She held the post through the 2021–2022 season.

Other notable conductors

[edit]Other conductors with whom the orchestra has had close ties include Sir John Barbirolli, Bruno Walter, Leopold Stokowski, Albert Coates, Fritz Reiner, and Erich Leinsdorf;[47] more recently, others have included Kurt Sanderling, Pierre Boulez, Leonard Bernstein, Charles Dutoit, Christoph Eschenbach, and Rafael Frühbeck de Burgos.

Many composers have conducted the Philharmonic in concerts and/or world premieres of their works, including Igor Stravinsky, William Kraft, John Harbison, Witold Lutosławski, Aaron Copland, Pierre Boulez, Steven Stucky, John Williams, Jerry Goldsmith, John Adams, Thomas Adès, and Esa-Pekka Salonen.

A number of the Philharmonic's Assistant/Associate Conductors have gone on to have notable careers in their own rights. These include Lawrence Foster, Calvin E. Simmons, and William Kraft under Mehta, Sidney Harth and Myung-whun Chung under Giulini, Heiichiro Ohyama and David Alan Miller under Previn, and Grant Gershon, Miguel Harth-Bedoya, Kristjan Järvi, and Alexander Mickelthwate under Salonen. Lionel Bringuier was originally named Assistant Conductor under Salonen before being promoted to Associate Conductor and, finally, Resident Conductor under Dudamel; since then, Mirga Gražinytė-Tyla has served as Assistant Conductor and Associate Conductor under Dudamel.

Other resident artists

[edit]Composers

[edit]- 1981–1985: William Kraft

- 1985–1988: John Harbison

- 1987–1989: Rand Steiger

- 1988–2009: Steven Stucky

- 2009–present: John Adams

Kraft and Harbison held the title "Composer-in-Residence" as part of a Meet the Composer (MTC) sponsorship. Steiger was given the title "Composer-Fellow", serving as an assistant to both Harbison and Stucky.[48]

Stucky was also a MTC "Composer-in-Residence" from 1988 to 1992, but was kept on as "New Music Advisor" after his official MTC-sponsored tenure ended; in 2000, his title was again changed to "Consulting Composer for New Music." In the end, his 21-year residency with the orchestra was the longest such relationship of any composer with an American orchestra.[48][49]

Adams has been named the orchestra's "Creative Chair" beginning in Fall 2009.

Artistic director and creative chairs for Jazz

[edit]- 2002–2006: Dianne Reeves

- 2006–2010: Christian McBride

- 2010–present: Herbie Hancock

Reeves was named the first "Creative Chair for Jazz" in March 2002. Instead of just focusing on summer programming, the new position involved the scheduling of jazz programming and educational workshops year round; as such, she led the development of the subscription jazz series the orchestra offered when it moved into Walt Disney Concert Hall. In addition, she was the first performer at the 2003 inaugural gala at the Walt Disney Concert Hall. Her contract was initially for two years, and was subsequently renewed for an additional two years.[50]

McBride took over the position in 2006 for an initial two-year position that was subsequently renewed for an additional two years through to the start of the 2010 summer season at the Hollywood Bowl. In 2009, the orchestra introduced Hancock as McBride's eventual replacement.

In 1998, prior to the establishment of the Creative Chair for Jazz, John Clayton was given the title "Artistic Director of Jazz" at the Hollywood Bowl for a three-year term beginning with the 1999 summer season. His band, the Clayton-Hamilton Jazz Orchestra, acted as the resident jazz ensemble.[15]

Recordings

[edit]The orchestra occasionally made 78-rpm recordings and LPs in the early years with Alfred Wallenstein and Leopold Stokowski for Capitol Records, and began recording regularly in the 1960s, for London/Decca, during the tenure of Zubin Mehta as music director. A healthy discography continued to grow with Carlo Maria Giulini on Deutsche Grammophon and André Previn on both Philips and Telarc Records. Michael Tilson Thomas, Leonard Bernstein, and Sir Simon Rattle also made several recordings with the orchestra in the 1980s, adding to their rising international profile. In recent years, Esa-Pekka Salonen has led recording sessions for Sony and Deutsche Grammophon. A recording of the Concerto for Orchestra by Béla Bartók released by Deutsche Grammophon in 2007 was the first recording by Gustavo Dudamel conducting the LA Phil.

The Los Angeles Philharmonic has performed music for motion pictures, such as the 1963 Stanley Kramer film It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World (composed by Ernest Gold), the pilot film of the original Battlestar Galactica TV show (composed by Stu Phillips and Glen A. Larson), and the most recent 2021 film version of the Broadway musical West Side Story (composed by Leonard Bernstein). The LA Philharmonic also performed the first North American concert for the Final Fantasy franchise game music, Dear Friends: Music From Final Fantasy by Nobuo Uematsu. The orchestra has most recently recorded the sound track for the video game: BioShock 2 as composed by Garry Schyman.

The album Fandango includes a performance of Alberto Ginastera's Four Dances from Estancia, recorded live at Walt Disney Concert Hall in October 2022 and Arturo Márquez's new violin concerto Fandango, written for violinist Anne Akiko Meyers.[51]

Recent world premieres

[edit]| Season | Date | Composer | Composition | Conductor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011–12[52] | October 20, 2011 | Enrico Chapela | Concerto for Electric Guitar | Gustavo Dudamel |

| November 11, 2011 | Richard Dubugnon | Battlefield | Semyon Bychkov | |

| November 25, 2011 | Anders Hillborg | Sirens | Esa-Pekka Salonen | |

| December 2, 2011 | Dmitri Shostakovich (posth.) | Prologue to Orango (reconstructed by Gerard McBurney) | Esa-Pekka Salonen | |

| April 10, 2012 | Oscar Bettison | Livre de Sauvages | John Adams | |

| May 8, 2012 | Joseph Pereira | Percussion Concerto | Gustavo Dudamel | |

| May 31, 2012 | John Adams | The Gospel According to the Other Mary | Gustavo Dudamel | |

| 2012–13[53] | September 28, 2012 | Steven Stucky | Symphony | Gustavo Dudamel |

| October 16, 2012 | Daníel Bjarnason | Over Light Earth | John Adams | |

| January 18, 2013 | Peter Eötvös | DoReMi | Pablo Heras-Casado | |

| February 26, 2013 | Unsuk Chin | Graffiti | Gustavo Dudamel | |

| February 26, 2013 | Joseph Pereira | Concerto for Percussion and Chamber Orchestra | Gustavo Dudamel | |

| April 16, 2013 | Matt Marks | TBD | Alan Pierson | |

| April 18, 2013 | Ted Hearne | But I Voted for Shirley Chisholm | Joshua Weilerstein | |

| 2014–15[54] | November 20, 2014 | Stephen Hartke | Symphony No. 4 "Organ" | Gustavo Dudamel |

| May 14, 2015 | Kaija Saariaho | True Fire | Gustavo Dudamel | |

| May 26, 2015 | Christopher Cerrone Sean Friar Dylan Mattingly |

The Pieces That Fall to Earth Finding Time Seasickness and Being (in love) |

John Adams | |

| May 28, 2015 | Bryce Dessner Philip Glass |

Quilting Concerto for Two Pianos |

Gustavo Dudamel | |

| May 29, 2015 | Steven Mackey | Mnemosyne's Pool | Gustavo Dudamel | |

| 2015–16 | 2016-02-25 | Andrew Norman | Play: Level 1 | Gustavo Dudamel |

| 2016-05-06 | Louis Andriessen | Theatre of the World | Reinbert de Leeuw | |

| 2016-05-28 | Arvo Pärt | Greater Antiphons | Gustavo Dudamel | |

| 2016–17 | 2017-02-24 | James Matheson | Unchained | James Gaffigan |

| 2017-04-15 | María Huld Markan Sigfúsdóttir | Aequora | Esa-Pekka Salonen | |

| 2017–18 | 2017-10-12 | Gabriela Ortiz | Téenek – Invenciones de territorio | Gustavo Dudamel |

| 2017-10-15 | Arturo Marquez | Danzón No. 9 | Gustavo Dudamel | |

| 2017-12-02 | Tania Leon | Ser (Being) | Miguel Harth-Bedoya | |

| 2018-01-25 | Joseph Pereira | Concerto for timpani and two percussion | Gustavo Dudamel | |

| 2018-02-23 | Nico Muhly | Organ Concerto | James Conlon | |

| 2018-03-31 | Isaac Pross

Adam Karelin Benjamin Beckman |

Under the Table

Constructs a(de)scendance |

Ruth Reinhardt | |

| 2018-04-13 | Esa-Pekka Salonen | Pollux | Gustavo Dudamel | |

| 2018–19 | 2018-09-27 | Julia Adolphe | Underneath the Sheen | Gustavo Dudamel |

| 2018-09-30 | Paul Desenne | Guasamacabra | Gustavo Dudamel | |

| 2018-10-04 | Andrew Norman | Sustain | Gustavo Dudamel | |

| 2018-11-01 | Steve Reich | Music for Ensemble and Orchestra | Susanna Malkki | |

| 2018-11-18 | Christopher Cerrone | The Insects Became Magnetic | Roderick Cox | |

| 2019-01-10 | Philip Glass | Symphony No. 12 Lodger | John Adams | |

| 2019-02-07 | Du Yun | Thirst | Elim Chan | |

| 2019-02-17 | Adolphus Hailstork | Still Holding On | Thomas Wilkins | |

| 2019-03-07 | John Adams | Must the Devil Have All the Good Tunes? | Gustavo Dudamel | |

| 2019-04-05 | Unsuk Chin | SPIRA | Mirga Gražinytė-Tyla | |

| 2019-05-02 | Louis Andriesson | The only one | Esa-Pekka Salonen | |

| 2019-05-10 | Thomas Ades | Inferno | Gustavo Dudamel | |

| 2019–20 | 2019-10-03 | André Previn | Can Spring be Far Behind? | Gustavo Dudamel |

| 2019-10-10 | Esteban Benzecry | Piano Concerto "Universos infinitos" | Gustavo Dudamel | |

| 2019-10-19 | Esa-Pekka Salonen | Castor | Esa-Pekka Salonen | |

| 2019-10-24 | Daníel Bjarnason | From Space I saw Earth for three conductors | Gustavo Dudamel, Zubin Mehta, Esa-Pekka Salonen | |

| 2019-10-26 | Esa-Pekka Salonen | Castor and Pollux (Gemini) | Esa-Pekka Salonen | |

| 2019-10-27 | Gabriela Ortiz | Yanga | Gustavo Dudamel | |

| 2020-01-18 | Julia Wolfe | Flower Power | John Adams | |

| 2020-03-22 | Julia Adolphe | Cello Concerto (Postponed) | Karen Kamensek | |

| 2020–21 | 2021-08-24 | Arturo Marquez | Fandango -Violin Concerto, written for Anne Akiko Meyers | Gustavo Dudamel |

| 2021–22 | 2021-12-03 | Julia Adolphe | Woven Loom, Silver Spindle | Xian Zhang |

Awards

[edit]2010 & 2011, ASCAP Morton Gould Award for Innovative Programming

2012, ASCAP Award for Programming Contemporary Music

Grammy Award for Best Instrumental Soloist(s) Performance (with orchestra)

- 1997, The Three Piano Concertos by Béla Bartók, conducted by Esa-Pekka Salonen

Grammy Award for Best Orchestral Performance

- 2012, Symphony No. 4 by Johannes Brahms, conducted by Gustavo Dudamel

- 2020, Sustain by Andrew Norman, conducted by Gustavo Dudamel

- 2021, Complete Symphonies by Andrew Norman, conducted by Gustavo Dudamel

- 2024, Dante by Thomas Adès, conducted by Gustavo Dudamel

Grammy Award for Best Choral Performance

- 2022, Symphony No. 8 by Gustav Mahler, conducted by Gustavo Dudamel

Management

[edit]Funding

[edit]The Los Angeles Philharmonic's endowment grew significantly in the early 21st century, reaching around $255 million in 2017. In 2002, it received its largest gift to date when the Walt and Lilly Disney family donated $25 million to endow the music directorship. David Bohnett donated $20 million in 2014 to endow the orchestra's top administrative post and create a fund for technology and innovation.[55]

As of 2019, the Los Angeles Philharmonic's annual budget is at approximately $125 million.[56]

Chief executives

[edit]- 1969–1997: Ernest Fleischmann

- 1998–2000: Willem Wijnbergen

- 2000–2017: Deborah Borda

- 2017–2019: Simon Woods[57][56]

- 2019–present: Chad Smith[58]

See also

[edit]- Hollywood Bowl Orchestra

- Los Angeles Junior Philharmonic Orchestra

- Los Angeles Philharmonic discography

- Los Angeles Philharmonic Institute

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Ross, Alex (April 30, 2007). "The Anti-maestro; How Esa-Pekka Salonen transformed the Los Angeles Philharmonic". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved November 7, 2017.

- ^ Ross, Alex (January 7, 2008). "Maestra; Marin Alsop leads the Baltimore Symphony". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved November 7, 2017.

- ^ Patner, Andrew (April 10, 2007). "'Say it ain't so,' music fans lament; Triumphant CSO debut makes pain of losing him worse". Chicago Sun-Times.

- ^ Page, Tim (April 10, 2007). "Dudamel, 26, to Lead L.A. Orchestra". The Washington Post.

- ^ Jacobs, Tom. "A Conversation with Deborah Borda, President of the Los Angeles Philharmonic". The Independent. Archived from the original on September 27, 2013. Retrieved September 25, 2013.

- ^ Vincent, Roger (September 19, 2005). "Another L.A. Comeback: A landmark auditorium will reopen as part of the conversion of a defunct downtown hotel into the Gansevoort West". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 10, 2015.

- ^ a b c d Swed, Mark (August 31, 2003). "The Salonen-Gehry Axis". The Los Angeles Times Magazine. Archived from the original on March 11, 2007. Retrieved May 3, 2008.

- ^ a b Rich, Alan. "Los Angeles Philharmonic Story". The Los Angeles Philharmonic Inaugurates Walt Disney Concert Hall. PBS. Archived from the original on August 7, 2008. Retrieved May 3, 2008.

- ^ Glass, Herbert. "About the Piece: Symphony in Three Movements". Los Angeles Philharmonic. Archived from the original on January 27, 2013. Retrieved May 20, 2008.

- ^ Kennedy, Michael. Barbirolli, Sir John (1899–1970) Archived August 8, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edition, October 2009, (subscription required), accessed February 7, 2010.

- ^ Meckna, Michael (Fall 1998). "Alfred Wallenstein: An American Conductor at 100". The Society for American Music Bulletin. XXIV (3). Archived from the original on September 16, 2017. Retrieved June 12, 2010.

- ^ "Los Angeles Philharmonic Concert Listings, 1950–1960". CAMA Archives. Santa Barbara Community Arts Music Association. Archived from the original on June 2, 2008. Retrieved May 3, 2008.

- ^ a b c Leeds, Jeff (September 6, 1997). "Sir Georg Solti: Led Chicago Symphony to World Renown". The Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved November 6, 2017.

- ^ a b "Buffie & the Baton". Time. April 14, 1961. Archived from the original on February 4, 2011. Retrieved November 8, 2007.

- ^ a b c Bernheimer, Martin (October 8, 1989). "The Tyrant of Philharmonic". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Dutka, Elaine (November 11, 1998). "Bowl Reveals Tempo Changes". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 7, 2019. Retrieved September 23, 2009.

- ^ Holland, Bernard (August 22, 1999). "Off-the-Podium Intrigue Surrounds Two Leading Jobs". The New York Times. Retrieved May 3, 2008.

- ^ Swed, Mark (September 15, 2005). "He holds Bowl in palm of his hands". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on August 20, 2024. Retrieved August 15, 2024.

- ^ Swed, Mark (January 6, 2007). "Indoors or out, this guy's the real deal". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 17, 2023. Retrieved August 15, 2024.

- ^ "The Kids Are Alright". Spirit Magazine. March 2013.

- ^ Raftery, Brian (May 11, 2009). "The 2009 TIME 100 Finalists". Time.

- ^ Swed, Mark (October 3, 2009). "Bowled over by L.A.'s new maestro". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 1, 2013. Retrieved September 26, 2013.

- ^ Swed, Mark (October 9, 2009). "Music review: L.A. Phil embraces a new generation with Dudamel". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on September 21, 2017. Retrieved November 6, 2017.

- ^ "ASCAP Announces Year 2010 Orchestra Awards For "Adventurous Programming" at League of American Orchestras Conference in Atlanta" (Press release). ASCAP. June 18, 2010. Archived from the original on September 27, 2013. Retrieved September 26, 2013.

- ^ "ASCAP "Adventurous Programming" Awards Presented at League of American Orchestras Conference in Minneapolis" (Press release). ASCAP. June 9, 2011. Archived from the original on August 13, 2011. Retrieved July 29, 2011.

- ^ "ASCAP "Adventurous Programming" Awards Presented at League of American Orchestras Conference" (Press release). ASCAP. June 8, 2012. Retrieved November 6, 2017.

- ^ Swed, Mark (January 8, 2012). "Gustavo Dudamel's Mahler project". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on August 8, 2024. Retrieved August 15, 2024.

- ^ a b Swed, Mark (May 21, 2012). "Review: 'Don Giovanni' feels right at home in Disney Hall". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on August 19, 2024. Retrieved August 15, 2024.

- ^ Farber, Jim (May 19, 2013). "A Sublime Marriage of Figaro From L.A. Phil". San Francisco Classical Voice. Archived from the original on September 28, 2013. Retrieved September 26, 2013.

- ^ Jim Farber (May 27, 2014). "Sensual Success in L.A. Phil Così fan tutte". San Francisco Classical Voice. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ Tilden, Imogen (October 6, 2011). "Gustavo Dudamel named artist of the year at Gramophone awards". The Guardian. Manchester.

- ^ Ng, David (February 12, 2012). "Grammy Awards 2012: Gustavo Dudamel, L.A. Philharmonic win". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Boehm, Mike (November 7, 2012). "Gustavo Dudamel named musician of the year by Musical America". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 19, 2024. Retrieved August 15, 2024.

- ^ "Gustavo Dudamel and the Los Angeles Philharmonic win Grammy® Award for Best Orchestral Performance for Andrew Norman's Sustain". Los Angeles Philharmonic. January 26, 2020. Archived from the original on September 28, 2020. Retrieved March 30, 2021.

- ^ "LA Phil wins Grammy Award for Best Orchestral Performanc". Los Angeles Philharmonic. March 14, 2021. Archived from the original on March 30, 2021. Retrieved March 30, 2021.

- ^ "Adès' Dante wins Grammy Award for Best Orchestral Performance". Faber Music. February 9, 2024. Archived from the original on May 26, 2024. Retrieved May 18, 2024.

- ^ "Statement from the Los Angeles Philharmonic regarding the appointment of Gustavo Dudamel to the New York Philharmonic" (Press release). TLos Angeles Philharmonic. February 7, 2023. Archived from the original on February 8, 2023. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ "Los Angeles Philharmonic Association Appoints Kim Noltemy as President & Chief Executive Officer" (Press release). May 2, 2024. Archived from the original on May 6, 2024. Retrieved May 6, 2024.

- ^ Javier C. Hernández (May 1, 2024). "Kim Noltemy, Orchestra Veteran, Is Tapped to Lead L.A. Philharmonic". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 2, 2024. Retrieved May 2, 2024.

- ^ "History of the Los Angeles Philharmonic". Los Angeles Philharmonic. Archived from the original on January 14, 2008. Retrieved January 18, 2008.

- ^ Halpert, Marta (December 16, 2022). ""Für mein Leben habe ich kämpfen müssen"". Wina – Das jüdische Stadtmagazin (in German). Retrieved December 31, 2024.

- ^ a b "Los Angeles Philharmonic Creates New Honor for Esa-Pekka Salonen" (Press release). Los Angeles Philharmonic. April 19, 2009. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved November 6, 2017.

- ^ a b Haven, CK Dexter (January 4, 2019). "Zubin Mehta named LA Phil "Conductor Emeritus," will return in 2019/20 season". All is Yar (allisyar.com). Archived from the original on January 5, 2019. Retrieved January 4, 2019.

- ^ "Conductor Leonard Slatkin Opens Los Angeles Philharmonic's 2007 Season at Hollywood Bowl with Fireworks" (Press release). Los Angeles Philharmonic Association. July 10, 2007. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved July 10, 2007.

- ^ Pasles, Chris (March 18, 2000). "New conductors at Bowl Unveiled". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 7, 2019. Retrieved June 22, 2008.

- ^ Michael Cooper (April 6, 2016). "Susanna Malkki Named Principal Guest Conductor of Los Angeles Philharmonic". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 9, 2024. Retrieved May 6, 2024.

- ^ Muggeridge, Donald (1977). "A History of the Los Angeles Philharmonic". To the World's Oboists. 5 (2). The International Double Reed Society. Archived from the original on December 5, 2008. Retrieved June 18, 2008.

- ^ a b "Los Angeles Philharmonic New Music Group Celebrates 20th Anniversary" (Press release). Los Angeles Philharmonic. January 29, 2002. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved November 6, 2017.

- ^ "About the Composer: Steven Stucky". Los Angeles Philharmonic. Archived from the original on August 2, 2009. Retrieved September 23, 2009.

- ^ Haithman, Diane (March 28, 2002). "L.A. Phil Names Jazz Leader". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved November 7, 2017.

- ^ "Fandango". LA Phil. Archived from the original on November 15, 2024. Retrieved December 29, 2024.

- ^ Los Angeles Philharmonic announces 2011–12 season. Los Angeles Times, February 6, 2011.

- ^ 2012–13 schedule Los Angeles Philharmonic Archived November 18, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ 2013–14 schedule Los Angeles Philharmonic Archived November 18, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Geoff Edgers (December 10, 2014), A $20 million gift for the Los Angeles Philharmonic Archived May 3, 2021, at the Wayback Machine Washington Post.

- ^ a b Michael Cooper (September 17, 2019), Los Angeles Philharmonic's Chief Executive Abruptly Leaves Archived September 17, 2019, at the Wayback Machine New York Times.

- ^ Deborah Vankin (September 16, 2019), L.A. Phil Chief Executive Simon Woods resigns, leaving supporters 'stunned' Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Michael Cooper (October 1, 2019), This Time, the Los Angeles Philharmonic Promotes From Within Archived October 20, 2019, at the Wayback Machine New York Times.