Larissa Reissner

Larissa Reissner | |

|---|---|

Лариса Рейснер | |

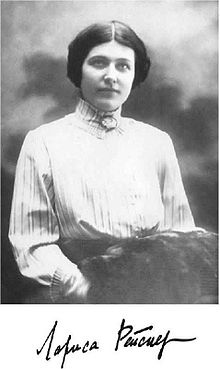

Larissa Reissner in 1920 | |

| Born | May 1, 1895 Lublin, Congress Poland, Russian Empire |

| Died | February 9, 1926 (aged 30) Moscow, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union |

| Alma mater | St. Petersburg Psychoneurological Institute |

| Spouse(s) | Fyodor Raskolnikov Karl Radek |

| Father | Mikhail Reisner |

Larissa Mikhailovna Reissner (Russian: Лариса Михайловна Рейснер; 13 [O.S. 1 May] May 1895 – 9 February 1926) was a Russian writer and revolutionary.[1] She is best known for her leadership roles on the side of the Bolsheviks in the Russian Civil War that followed the October Revolution and for her friendships with several Russian poets of the early 20th century.

Biography

[edit]Larissa Reissner was born in Lublin, Congress Poland, to Mikhail Andreevich Reisner, a jurist of Baltic German origin, then on the staff of the nearby Puławy Agricultural Institute, and his wife Ekaterina of the Russian noble Khitrovo family.[2][3]

She spent her early childhood in Tomsk, where her father was appointed Professor of Law at the University in 1897.[4] Between 1903 and 1907, she and her family resided in Berlin, Germany, where the family fled because of the father's political activity, with Larisa attending a primary school in the Zehlendorf district.[5] In the aftermath of the 1905-06 Russian Revolution, they moved to Saint Petersburg[6] where she passed her final school exams with a gold medal in 1912 and went on to study at St. Petersburg University, including studying courses at the Faculty of Law and Philology as well as psychoneurology at the Bekhterev Research Institute.[7]

During the First World War, she published an anti-war literary journal, Rudin, financially supported by her parents who pawned their possessions to fund it.[8][9]

Affair with Gumilyov

[edit]At the age of 20, Reisner met the poet Nikolai Gumilyov, then aged 29, in the audience at a cabaret called the 'Comedian's Halt', which opened in October 1915, and they became lovers, with nicknames for one another. She called him 'Gafiz'; he called her 'Lefi'. He was her first lover; she idolised him, and tried to imitate his poetry. She also met Gumilyov's wife, the poet Anna Akhmatova, at the Comedian's Halt (or Stray Dog according to Larissa Reissner "Autobiographic Novel") and burst into tears of gratitude when Akhmatova shook hands with her. Akhmatova later said: "What was this all about? ... How could I have known then that she was having an affair with Gumilyov? And even if I had known — why wouldn't I have given her my hand?"[10] He wrote passionate letters to her while he was away on war service, and may also have offered to marry her, but during 1916 she learnt that he was simultaneously having an affair with another woman. They met for the last time in April 1917, and in his last postcard to her, he urged her not to get involved in politics.[11]

Revolution and the Civil War

[edit]After the February Revolution, Larisa began to write for Maxim Gorky's paper Novaya Zhizn (New Life).[9][12] She also took part in the Provisional Government's spelling reform programme, teaching at workers' and sailors' clubs in Petrograd.[13]

A week after the Bolshevik Revolution, Reisner helped the newly appointed People's Commissar Anatoly Lunacharsky to issue an appeal to Petrograd's artists and cultural workers to assemble at an evening meeting in the Smolny Institute, where the Bolsheviks had their headquarters, to show support for the regime. The turnout was so poor that "there was enough room to sit on one sofa" — but it included three major figures in Russian culture, the poets Alexander Blok and Vladimir Mayakovsky and the theatre director Vsevolod Meyerhold, who spent hours discussing how to organise the intelligentsia.[14] Later, she worked at the Smolny Institute with Lunacharsky, cataloguing art treasures.[15][16] In 1917, as part of Maxim Gorky's team, she helped the Jewish plea, presented by Joseph Kruk, whom later testified for this episode, to avoid collecting weapons from Jews, gathered already in the times of the Zar regime, as part of Jewish organizing themselves for self-defence vis-a-vis threats made by The Black Hundreds also after the revolution. With her intermediation Gorky ensured that Lenin will see that anti Jewish riots will be prevented.

She became a member of the Bolshevik Party in 1918, marrying Fyodor Raskolnikov in the summer of that year.[17] During the Civil War, she was a soldier and a political commissar of the Red Army. She served as chief of an intelligence section of the Volga River flotilla in August 1918 battle for Sviazhsk.[18] During 1919, she served as the Commissar at the Naval Staff Headquarters in Moscow.[19]

Relations with poets

[edit]Reisner was on friendly terms with Osip Mandelstam, who prevailed upon her in 1918 to accompany him in approaching Felix Dzerzhinsky, head of the feared Cheka, to plead for the life of an aristocratic art historian — whom neither of them knew — who was under sentence of death. Mandelstam was evidently impressed both by her determination — he described her as "heavy artillery" — and by elegance of her movements. "She danced along like a wave on the sea," he said.[20] In 1921, Reisner invited Mandelstam and his wife Nadezhda to accompany her to Afghanistan. They wanted to go, but Raskolnikov, who did not like Mandelstam, vetoed the idea.[21]

In 1920, she took revenge on Gumilyov for his infidelity, by arranging for the rations he was receiving from the Baltic Fleet to be cancelled. She sent a bag of rice to Anna Akhmatova, who was close to starvation, and met her to complain bitterly about how Gumilyov had treated her. After the meeting, in Reisner's flat overlooking the Neva, she gave Akhmatova a lift home in her horse drawn cab, and told her: "I would give everything, absolutely everything to be Anna Akhmatova." She presumably meant that she wished she had Akhmatova's poetic gift, but Akhmatova was not flattered. She told Lydia Chukovskaya: "stupid words, aren't they? What does that mean — everything? Three windows on the Neva?"[22] While she was in Kabul, Reisner learnt that Blok had died, and wrote a passionate letter to Akhmatova, saying: "Now, when he no longer exists, your equal, your only spiritual brother... Most tender poet. are you still writing poems?... don't be silent — do not die while still alive."[23]

Shortly afterwards, she heard that Gumilyov had been executed, and wished that she had been on hand to intervene and save his life. Her mother, who was in Russia, also bitterly regretted not realising the danger Gumilyov was in when she heard that he had been arrested. Nadezhda Mandelstam believed that Reisner might have saved Gumilyov, because "the one thing Larisa could not overcome was her love of poetry... Larisa not only loved poetry, but she also secretly believed in its importance, and for her the only blot on the Revolution's record was the shooting of Gumilyov... I somehow believe that if she had been in Moscow when Gumilyov was arrested, she would have got him out of jail, and if she had been alive and still in favour with the regime during the time when M. (Osip Mandelstam) was being destroyed, she would have moved heaven and earth to try and save him."[24]

International affairs

[edit]In 1921, while married to Raskolnikov, she and her husband traveled to Afghanistan as representatives of the Soviet Republic, carrying out diplomatic negotiations.[25]

In October 1923 she traveled illegally to Germany to witness the revolution there first-hand and write about it, producing collections of articles entitled Berlin, October 1923[26] and Hamburg at the Barricades.[27]

During her stay in Germany she had become Karl Radek's lover.[28] On her return to Russia she and Raskolnikov divorced in January 1924.[29] The failure of the German revolution provoked furious arguments in the USSR about whose fault it was. Aino Kuusinen, wife of Otto Kuusinen, secretary of the Comintern, described one such dispute that broke out when visitors gathered in her husband's flat:

There was another knock: this time it was Karl Radek, whom I knew, accompanied by a very good-looking woman. He introduced her; the name meant nothing to me. A third knock Bela Kun appeared... A furious argument began between him and Ernst Thälmann, each accusing the other...I sat on the sofa with Radek's friend, while the two men remained standing and continued to argue fiercely. I was amazed that they did so in the presence of an outsider, for the young woman did not belong to the Comintern and I had no notion why she was there. Radek was calm at first, but suddenly he joined in the quarrel and all three men shouted at once...Suddenly, to my astonishment, the woman jumped up and stood between Radek and Thälmann, shaking her fist at the latter and calling him a brainless prize-fighter and other uncomplimentary things....Suddenly the woman flew at Thälmann, tugging at his coat and hammering with her fists...To Otto, when they left our apartment, I said: 'Isn't it disgraceful of the men to go on like that in front of an outsider. He replied: 'She's not an outsider - she's Radek's friend, Larissa Reissner.[30]

It has also been suggested that she was briefly the lover of Liu Shaoqi, who rose to be the third most powerful leader in the communist China.[31] This story appears to have originated from a biography of Liu by a German communist named Hans Heinrich Wetzel, a book scathingly likened by one reviewer to Ian Fleming's novel From Russia with Love.[32] Reisner was in Kabul during the entire time that Liu was in Moscow, where the 'affair' is supposed to have been conducted.

Final years

[edit]During 1924–1925, she worked as a special correspondent for Izvestiya, first in the Northern Urals where she adopted a boy by the name of Alyosha Makarov.[33] Her later writings came from Hamburg, whilst she was visiting a malaria clinic near Wiesbaden.[34] She also wrote articles on a corruption scandal in Byelorussia.[35] During this time, she also worked on Leon Trotsky's Commission for Improvement of Industrial Products.[36]

Larissa Reissner died on 9 February 1926, in the Kremlin Hospital, Moscow, from typhoid; she was 30 years old.[37]

Tributes

[edit]In his autobiography My Life the Bolshevik leader and founder of the Red Army Leon Trotsky paid tribute to her:

"Larissa Reisner [...] was herself prominent in the Fifth army, as well as in the revolution as a whole. This fine young woman flashed across the revolutionary sky like a burning meteor, blinding many. With her appearance of an Olympian goddess, she combined a subtle and ironical mind with the courage of a warrior. After the capture of Kazan by the Whites, she went into the enemy camp to reconnoitre, disguised as a peasant woman. But her appearance was too extraordinary, and she was arrested. While she was being cross-examined by a Japanese intelligence officer, she took advantage of an interval to slip through the carelessly guarded door and disappear. After that, she engaged in intelligence work. Later, she sailed on war-boats and took part in battles. Her sketches about the civil war are literature. With equal gusto, she would write about the Ural industries and the rising of the workers in the Ruhr. She was anxious to know and to see all, and to take part in everything. In a few brief years, she became a writer of the first rank. But after coming unscathed through fire and water, this Pallas of the revolution suddenly burned up with typhus in the peaceful surroundings of Moscow."[38]

Almost every memoirist who knew Reisner, apart from Trotsky, felt moved to remark on her beauty. Anna Akhmatova described her as "a beautiful young woman" later remarking: "No-one would ever have imagined I would outlive Larisa... She wanted so much to live; she was cheerful, healthy, beautiful."[39] Nadezhda Mandelstam remembered her as "beautiful in a heavy and striking Germanic way."[40] The critic Viktor Shklovsky variously described her as "the young lovely", and "beautiful"[41] Alexander Barmine described her as "a slender young woman with auburn curls and the beauty of a Minerva without her helmet."[42] Alexander Voronsky wrote that "her noble face was both strong-willed and feminine, reminding one of the legendary Amazons, and was framed by chestnut... this beautiful and truly rare example of the human species."[43]

References

[edit]- ^ "Larisa Mikhailovna Reisner".

- ^ Radek, K. (1977) "Larissa Reisner" In Reissner, L. Hamburg At the Barricades and Other Writings of Weimar Germany London: Pluto pg.186

- ^ Porter, C. (1988) Larissa Reisner, London: Virago pg.9

- ^ Porter, C. (1988) Larissa Reisner, London: Virago pg.11

- ^ Porter, C. (1988) Larissa Reisner, London: Virago pg.12

- ^ Radek, K. (1977) "Larissa Reisner" In Reissner, L. Hamburg At the Barricades and Other Writings of Weimar Germany London: Pluto pg.187

- ^ Porter, C. (1988) Larissa Reisner, London: Virago pg.22-23

- ^ Porter, C. (1988) Larissa Reisner, London: Virago pg.32-33

- ^ a b Radek, K. (1977) "Larissa Reisner" In Reissner, L. Hamburg At the Barricades and Other Writings of Weimar Germany London: Pluto pg.189

- ^ Reeder, Roberta (1995). Anna Akhmatova, Poet & Prophet. London: Allison & Busby. pp. 92–93. ISBN 0-85031-998-6.

- ^ Reeder. Anna Akhmatova. p. 116.

- ^ Porter, C. (1988) Larissa Reisner, London: Virago pg.41

- ^ Porter, C. (1988) Larissa Reisner, London: Virago pg.42

- ^ Woroszylski, Wiktor (1970). The Life of Mayakovsky. New York: The Orion Press. pp. 186–7.

- ^ Porter, C. (1988) Larissa Reisner, London: Virago pg.45-46

- ^ Radek, K. (1977) "Larissa Reisner" In Reissner, L. Hamburg At the Barricades and Other Writings of Weimar Germany London: Pluto pg.189-190

- ^ Porter, C. (1988) Larissa Reisner, London: Virago pg.53

- ^ Pennington, Reina (2003). Amazons to Fighter Pilots - A Biographical Dictionary of Military Women (Volume Two). Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. p. 358. ISBN 978-0-313-32708-7.

- ^ Radek, K. (1977) "Larissa Reisner" In Reissner, L. Hamburg At the Barricades and Other Writings of Weimar Germany London: Pluto pg.191

- ^ Gerstein, Emma (2004). Moscow Memoirs. Woodstock, New York: The Overlook Press. pp. 7–8. ISBN 978-1-58567-595-1.

- ^ Mandelstam, Nadezhda (1971). Hope Against Hope, a Memoir. London: Collins & Harvill. pp. 105–06, 111. ISBN 0-00-262501-6.

- ^ Reeder. Anna Akhmatova. pp. 129–130.

- ^ Reeder. Anna Akhmatova. p. 141.

- ^ Mandelstam. Hope Against Hope. pp. 109, 111.

- ^ Porter, C. (1988) Larissa Reisner, London: Virago pg.112

- ^ Larissa Reissner (1924). "Berlin, October 1923". marxists.org. Marxists Internet Archive. Retrieved 19 September 2014.

- ^ Larissa Reissner (1924). "Hamburg at the Barricades". marxists.org. Marxists Internet Archive. Retrieved 19 September 2014.

- ^ Porter, C. (1988) Larissa Reisner, London: Virago pg.143

- ^ Porter, C. (1988) Larissa Reisner, London: Virago pg.149

- ^ Kuusinen, Aino (1972). Before and After Stalin. London: Michael Joseph. pp. 64–65. ISBN 0-7181-1248-2.

- ^ eg see Jung Chang, and Joh Halliday (2006). Mao, the Unknown Story. London: Vintage. p. 263. ISBN 9780099507376.

- ^ Boorman, Howard L. (July–September 1965). "Liu Shao Chi: le moine rouge by Hans Heinrich Wetzel". The China Quarterly. 23 (23): 187–89. doi:10.1017/S0305741000010018. JSTOR 651737. S2CID 154680288.

- ^ Porter, C. (1988) Larissa Reisner, London: Virago pg.154-155

- ^ Porter, C. (1988) Larissa Reisner, London: Virago pg.158

- ^ Porter, C. (1988) Larissa Reisner, London: Virago pg.160

- ^ Porter, C. (1988) Larissa Reisner, London: Virago pg.159-160

- ^ Porter, C. (1988) Larissa Reisner, London: Virago pg.172

- ^ Trotsky, Leon (1975). My Life: An Attempt at an Autobiography. Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin. pp. 425–26.

- ^ Reeder. Anna Akhmatova. pp. 93, 141.

- ^ Mandelstam. Hope Against Hope. pp. 111–112.

- ^ Worosylski. The Life of Mayakovsky. pp. 154, 172.

- ^ Barmine, Alexander (1945). One Who Survived, The Life Story of a Russian under the Soviets. New York: G.P.Putnam's Sons. p. 139.

- ^ Voronsky, Aleksandr (1998). Art as the Cognition of Life, Selected Writings 1911-1936. Oak Park, Michigan: Mehring Books. pp. 248–9. ISBN 978-0-929087-76-4.