Miguel de la Madrid

Miguel de la Madrid | |

|---|---|

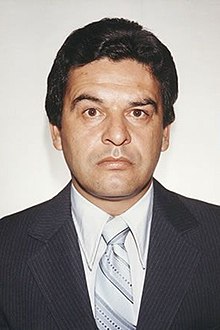

Official portrait, 1982 | |

| 59th President of Mexico | |

| In office 1 December 1982 – 30 November 1988 | |

| Preceded by | José López Portillo |

| Succeeded by | Carlos Salinas de Gortari |

| Director of the Fund of Economic Culture | |

| In office 15 January 1990 – 13 December 2000 | |

| Preceded by | Enrique González Pedrero |

| Succeeded by | Gonzalo Celorio Blasco |

| Secretary of Programming and the Budget of Mexico | |

| In office 16 May 1979 – 30 September 1981 | |

| President | José López Portillo |

| Preceded by | Ricardo García Sainz |

| Succeeded by | Ramón Aguirre Velázquez |

| Deputy Secretary of Finance and Public Credit of Mexico | |

| In office 29 September 1975 – 16 May 1979 | |

| President | Luis Echeverría (1975–76) José López Portillo (1976–79) |

| Secretary | Mario Ramón Beteta (1975–76) Julio Rodolfo Moctezuma (1976–77) David Ibarra Muñoz (1976–79) |

| Preceded by | Mario Ramón Beteta |

| Succeeded by | Jesús Silva-Herzog Flores |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Miguel de la Madrid Hurtado 12 December 1934[1] Colima, Mexico |

| Died | 1 April 2012 (aged 77) Mexico City, Mexico |

| Resting place | Iglesia de Santo Tomás |

| Political party | Institutional Revolutionary Party |

| Spouse | [2] |

| Children | 5 including Enrique |

| Alma mater | National Autonomous University of Mexico (LLB) Harvard University (MPA) |

Miguel de la Madrid Hurtado (Spanish pronunciation: [miˈɣel de la maˈðɾið uɾˈtaðo]; 12 December 1934 – 1 April 2012) was a Mexican politician affiliated with the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) who served as the 59th president of Mexico from 1982 to 1988.[1]

Inheriting a severe economic and financial crisis from his predecessor José López Portillo as a result of the international drop in oil prices and a crippling external debt on which Mexico had defaulted months before he took office, De la Madrid introduced sweeping neoliberal policies to overcome the crisis, beginning an era of market-oriented presidents in Mexico, along with austerity measures involving deep cuts in public spending. In spite of these reforms, De la Madrid's administration continued to be plagued by negative economic growth and inflation for the rest of his term, while the social effects of the austerity measures were particularly harsh on the lower and middle classes, with real wages falling to half of what they were in 1978 and with a sharp rise in unemployment and in the informal economy by the end of his term.[3]

De la Madrid's administration was also famous for his "Moral Renovation" campaign, whose purported goal was to fight the government corruption that had become widespread under previous administrations, leading to the arrests of top officials of the López Portillo administration.

In addition, his administration was criticized for its slow response to the 1985 Mexico City earthquake, and the handling of the controversial 1988 elections in which the PRI candidate Carlos Salinas de Gortari was declared winner, amid accusations of electoral fraud.

Early life and education

[edit]Miguel de la Madrid was born in the city of Colima, Colima, Mexico. He was the son of Miguel de la Madrid Castro, a notable lawyer (who was assassinated when his son was only two),[4] and Alicia Hurtado Oldenbourg. His grandfather was Enrique Octavio de la Madrid, the governor of Colima.

He graduated with a bachelor's degree in law from the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) and received a master's degree in Public Administration from the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University, in the United States.[1]

In 1953, he was introduced to Paloma Cordero by her older brother.[5] The couple began dating in 1955 and married four years later at the Santa Rosa de Lima Church in Cuauhtémoc in 1959.[5] Cordera and de la Madrid had five children - Margarita, Miguel, Enrique Octavio, Federico Luis and Gerardo Antonio.[5]

Early career

[edit]He worked for the Bank of Mexico and lectured in law at UNAM before he got a position at the Secretariat of Finance in 1965. Between 1970 and 1972, he was employed by Petróleos Mexicanos, Mexico's state-owned petroleum company, after which he held several other bureaucratic posts in the government of Luis Echeverría. In 1979, he was chosen to serve in José López Portillo's cabinet as Secretary of Budget and Planning, replacing Ricardo García Sainz.[1]

1982 election

[edit]De la Madrid had no political experience as an elected official prior to becoming the candidate for the PRI. In the assessment of political scientist Jorge G. Castañeda, López Portillo designated De la Madrid as a candidate by elimination, not by choice, and that De la Madrid remained in contention as a candidate because he was never the bearer of bad news to the president. Other contenders were Javier García Paniagua and David Ibarra Muñoz.[6] When his candidacy was revealed, his "candidacy was greeted with unusual hostility from some sectors of the political establishment--an indication of the emerging rift between the old políticos and emerging technocrats."[7] De la Madrid did not run against a strong opposition candidate. His campaign rhetoric emphasized traditional liberal values of representation, federalism, strengthening of the legislature and the judiciary. There was massive turnout in the election, for the first time in many years, voting overwhelmingly for De la Madrid.[8]

Presidency

[edit]De la Madrid inherited the financial catastrophe from his predecessor; Mexico experienced per capita negative growth for his entire term. De la Madrid's handling of the devastating 1985 Mexico City earthquake was his own major misstep. The end of his administration was even worse, with his choice of Carlos Salinas de Gortari as his successor, the split in the PRI with the exit of Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas, and the government's handling of balloting with election results deemed fraudulent. His administration did have some bright spots, with Mexico's becoming a member of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) in 1985. Mexico also was part of the Contadora process to find a solution of the conflicts in Central America.[9]

Economic policy

[edit]

Unlike previous Mexican leaders, he was a market-oriented president. Inflation increased on an average of 100% a year and reached to an unprecedented level of 159% in 1987. The underemployment rate soared to 25% during the mid-1980s, income declined, and economic growth was erratic since prices rose usually much faster than incomes.

All that was a stark reminder of the gross mismanagement and policies of his two immediate predecessors, particularly the financing of development with excessive overseas borrowing, which was often countered by high internal capital flights.[10] De la Madrid himself had been Minister of Budget and Programming under López Portillo, and as such he was perceived by many as being co-responsible for the crisis that he himself had to deal with upon taking office. As an immediate reaction to the economic crisis, he first presented the Immediate Economic Reorganization Program (Programa Inmediato de Reordenación Económica) and, a couple of months later, the National Development Plan (Plan Nacional de Desarrollo). Some of the measures proposed were a reduction of public spending, fiscal reforms, a restructuring of the bureaucracy, and employment protection.[11]

During his presidency, De la Madrid introduced neoliberal economic reforms that encouraged foreign investment, widespread privatization of state-run industries, and reduction of tariffs, a process that continued under his successors, and which immediately caught the attention of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and other international observers. In January 1986, Mexico entered the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) following its efforts at reforming and decentralizing its economy. The number of state-owned industries went down from approximately 1,155 in 1982 to 412 in 1988. De la Madrid re-privatized companies that had been made state-run under his predecessors. He sought better public-private sector relations, but the private sector began backing opposition candidates nonetheless. Given the dire economic circumstances he inherited from his predecessor, he pursued policies of economic austerity, rather than deficit spending.[12]

Domestic elections

[edit]President De la Madrid initially stated that further democratization of the country was necessary, and the political system opened up to greater competition. As other parties showed the potential for their electoral success, however, his attitude later seemed to be hostile to the advance of opposition parties, instead allowing the PRI to maintain near-absolute power of the country[13][14] (at the time, the PRI still governed all of the Mexican states plus the Federal District, in addition to holding 299 of the 400 seats in the Chamber of Deputies and 63 of the 64 seats in the Senate). However, it was during his administration that the opposition National Action Party (also known as "PAN" for its initials in Spanish) started to become popular with the masses, especially in Northern Mexico.

In 1983, during the municipal elections in the northern state of Chihuahua, the PAN won the state's nine biggest Municipalities, which held 70% of its population. The border state had been one of the most affected by the government's policies, specially the nationalization of the Bank decreed in the last months of former President López Portillo's administration.[15] Rather than accepting that the unpopularity and corruption of the PRI in Chihuahua had led to such a defeat, the local PRI bosses claimed that the Catholic Church, the local businessmen and even "foreign influences" had persuaded voters to support the PAN. Most importantly, the local PRI stated that the electoral defeat was a "tragic disaster" that should never be repeated.[16]

The 1986 gubernatorial elections in that same state [es] were marked by accusations of Electoral fraud. Although the PRI candidate, Fernando Baeza, was officially pronounced winner, the PAN candidate Francisco Barrio Terrazas, who officially ended in second place with 35.16% of the vote (at the time, the biggest percentage of votes that an opposition candidate had earned in Chihuahua) did not recognize the results, and the PAN promoted acts of civil disobedience to resist the alleged fraud. Many other local elections were marked by accusations of fraud in those years, sometimes ending with violent clashes. In some small municipalities of Veracruz and Oaxaca, the local population even seized or burned the local Town halls in response to alleged electoral frauds.[15]

Electoral reform

[edit]In response to these controversies, an electoral reform was conducted in 1986:

- The number of members of the Chamber of Deputies being elected by proportional representation (plurinominales) was increased from 100 to 200 and allowed for a better representation of opposition parties.

- The Senate is composed of two senators from each state and two from the Federal District of Mexico. An election of half of its members takes place every three years.

- The Legislative Assembly of the Federal District of Mexico was created.[17]

Attempt to legalize abortion

[edit]Since his campaign for the presidency, De la Madrid had mentioned the importance of discussing the topic of abortion, given the high national demographic growth and the scarce resources that the country had to deal with the necessities of an ever-growing population, specially in the middle of the economic crisis.[18]

Upon becoming President, De la Madrid and the Attorney General Sergio García Ramírez attempted to reform the Penal Code of the Federal District to decriminalize abortion during the first trimester of pregnancy "due to failure of the contraceptive methods, fetal alterations and pregnancies due to rape, with previous medical authorization and carried out at a hospital center".[19] However, due to the highly negative reaction of the Catholic church and the conservative sectors, the initiative was finally withdrawn.[20][21]

1984 Molotov cocktail attack

[edit]On 1 May 1984, an anti-government activist named José Antonio Palacios Marquina, along with others, threw Molotov cocktails at the balcony of the Presidential Palace, where De la Madrid was reviewing the May Day parade. Although the President was unharmed, the incident left many officials and guests injured, including the then-director of the ISSTE, Alejandro Carrillo.[22][23][24]

San Juanico explosions

[edit]

On 19 November 1984, a massive series of explosions occurred at a liquid petroleum gas (LPG) tank farm in the town of San Juan Ixhuatepec (outside of Mexico City, Mexico).[25] The disaster was initiated by a gas leak on the site, likely caused by a pipe rupture during transfer operations, which caused a plume of LPG to concentrate at ground level for 10 minutes. The plume eventually grew large enough to drift on the wind towards the west end of the site, where the facility's waste-gas flare pit was located. The explosions devastated the town of San Juan Ixhuatepec, and resulted in 500-600 deaths and 7,000 people with severe injuries.

The tragedy sparked a national outrage, and President De la Madrid visited the affected area on 20 November. He instructed the creation of a commission to help the survivors and to rebuild the destroyed homes. On 22 December, the Procuraduría General de Justicia found the state-run oil company Pemex to be responsible for the incident, and was ordered to pay indemnification to the victims. Due to the tragedy apparently having been caused by corruption and incompetence at the state-run company, the public further resented the Government and public institutions.[26]

1985 Earthquake

[edit]

In the morning of 19 September 1985, an 8.0 magnitude earthquake devastated Mexico City and caused the deaths of at least 5,000 people. De La Madrid's mishandling of the disaster damaged his popularity because of his initial refusal of international aid. It placed Mexico's delicate path to economic recovery in an even more precarious situation, as the destruction extended to other parts of the country.[2]

The federal government's first public response was President de la Madrid's declaration of a period of mourning for three days starting from 20 September 1985.[27]

De la Madrid initially refused to send the military to assist on the rescue efforts, and it was later deployed to patrol streets only to prevent looting after a curfew was imposed.[28]

The earthquake created many political difficulties for the then-ruling Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI) or Institutional Revolutionary Party. The crisis was severe enough to have tested the capabilities of wealthier countries, but the government from local PRI bosses to President de la Madrid himself exacerbated the problem aside from the lack of money. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs declared it would not request aid.[29]

It was also widely reported in the days after the earthquake that the military assisted factory owners in retrieving their machinery rather than in removing the bodies of dead factory workers.[30]

President de la Madrid was also criticized for refusing to cut foreign debt payments to use the money to help with the recovery effort (at the time, his administration destined around 30% of the federal budget towards the payments of the foreign debt). The government's response to the earthquake was widely criticized at various levels of Mexican society, being seen as both authoritarian and incompetent.[29] As most of the collapsed buildings were of recent construction and public works projects, the government was seen at fault due to mismanagement and corruption in these constructions.[31] The government itself realized that it could not handle the crisis alone through already-established institutions and decided to open the process up to "opposition groups".[29]

1986 FIFA World Cup

[edit]During his administration, Mexico hosted the 1986 FIFA World Cup. There were some protests against the tournament, as Mexico was going through an economic crisis at the time and the country was still recovering from the 1985 earthquake, therefore the World Cup was considered by many as a lavish and unnecessary expense.[32] During the World Cup's inauguration at the Estadio Azteca on 31 May, just before the opening match Italy vs Bulgaria, De la Madrid was jeered by a crowd of 100,000 while trying to give a speech,[33] apparently in protest over his administration's poor reaction to the 1985 earthquake.[34][35][36] An official who was present at the event recalled that "[The President's] words were completely drowned out by boos and whistles [...] I was dying with embarrassment, but it seemed to be the right metaphor for the mood of the country."[37]

Split in the PRI

[edit]In October 1986, a group of politicians from the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) led by Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas, Porfirio Muñoz Ledo and Ifigenia Martínez, announced the creation of the Democratic Current (Corriente Democrática) within the PRI. The Democratic Current demanded the establishment of clear rules for the selection of the party's presidential candidate. When they failed, Cárdenas, Muñoz Ledo and Martínez left the PRI the following year and created the National Democratic Front (Frente Democrático Nacional), a loose alliance of left-wing parties.[38]

Drug trafficking

[edit]

As the U.S. consumption of illegal substances grew in the 1960s and 1970s, the U.S. became interested in strengthening enforcement of drug trafficking in Mexico. In the 1980s U.S. Presidents Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush expanded the so-called "war on drugs" to stop drugs at ports of entry from Mexico. More importantly, the U.S. began asserting extraterritorial jurisdiction over drug trafficking in Mexican national territory.[39] The crackdown on drug trafficking resulted in higher prices for drugs, since there was more risk involved, but trafficking in this era boomed. Drug trafficking organizations in Mexico grew in size and strength. As the U.S. asserted jurisdiction over trafficking in Mexico, Mexico could no longer pursue an autonomous drug policy. Agents of the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) began operating in Mexico without the consent of Mexican authorities. "In 1987, De la Madrid declared drug trafficking a national security problem and completely reorganized Mexican antidrug policy" and more government financial and personnel resources were devoted to the policy. Arrests in 1987 for drug trafficking reached 17,000. Front-line enforcement agents of the Mexican police were often corrupted by bribes from drug traffickers. Violence between traffickers and the police increased in this period.[40] A major incident in the drug war and in U.S.-Mexican relations was the kidnap, torture, and murder of DEA agent Enrique "Kiki" Camarena in 1985. In 1984, the Mexican government had staged a raid on a suspected site of drug trafficking in Chihuahua state. Traffickers suspected Camarena of providing information to the Mexican government and he was abducted in February 1985, tortured and killed; his body was found a month later. The U.S. responded by sending a special unit of the DEA to coordinate the investigation in Mexico. In the investigation, Mexican government officials were implicated, including Manuel Ibarra Herrera, past director of Mexican Federal Judicial Police, and Miguel Aldana Ibarra, the former director of Interpol in Mexico.[41] Drug trafficking as an issue has continued in Mexico in succeeding presidential administrations.

Foreign policy

[edit]

In 1983, the Contadora Group was launched by Colombia, Panama, Venezuela and Mexico to promote peace in Latin America and to deal with the armed conflicts in El Salvador, Nicaragua, and Guatemala.[42]

On 31 March 1986, the Mexicana Flight 940 crashed in the state of Michoacán, killing everyone on board. Initially, two Middle Eastern terrorist groups claimed responsibility for this crash, along with the bombing of TWA Flight 840, which occurred just two days later. An anonymous letter signed by those groups claimed that a suicide mission had sabotaged the plane in retaliation against the United States.[43][44] However, sabotage was later dismissed as a cause of the crash, and the investigations carried out by the U.S. National Transportation Safety Board and Mexican aeronautical authorities concluded that the cause of the accident was that the center landing gear tire was filled with compressed air, instead of nitrogen.[45]

1988 election

[edit]Galloping inflation, the controversial privatization program and austerity measures imposed by his administration caused the ruling party to lose ground, leading up to the controversial elections of 1988. In the assessment of political scientist Roderic Ai Camp, "It would be fair to say that the election of Carlos Salinas de Gortari in 1988 marked the low point of that office as well as the declining legitimacy of the state."[46] In 1987, an internal conflict led to a division in the PRI, as President De la Madrid, like previous PRIísta Presidents had traditionally done, handpicked his successor for the Presidency and appointed the Secretary of Budget and Programming, Carlos Salinas de Gortari, as the PRI candidate for the 1988 elections.[47] A group of left-wing PRI politicians, led by Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas (the son of former President Lázaro Cárdenas) and Porfirio Muñoz Ledo, protested Salinas' appointment as they demanded that the PRI should put an end to the practice of the President choosing his own successor, and proposed that the PRI Presidential candidate should be democratically chosen by all of the PRI members through a convention. They also claimed that President De la Madrid had gone too far with his austerity and free-market reforms, and that his protégée Salinas represented a continuation of such policies.[47] After many public discussions and proposals, the leadership of the PRI stood by President De la Madrid and confirmed Salinas as the party's presidential candidate, while expelling Cárdenas and Muñoz Ledo from the PRI, along with their followers.[47]

For the first time since the PRI took power in 1929, the elections featured two strong opposition candidates with enough popularity to beat the PRI candidate. On one hand, after he and Muñoz Ledo were expelled from the PRI, Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas was nominated presidential candidate by the Frente Democrático Nacional, a coalition of leftist parties. Cárdenas attained massive popularity as result of his efforts at democratizing the PRI, his successful tenure as Governor of Michoacán, his opposition to the austerity reforms and his association with his father's nationalist policies.[48] On the other hand, the right-wing opposition party PAN nominated Manuel Clouthier as their presidential candidate. A businessman-turned-politician, Clouthier became popular, specially in Northern Mexico, for his populist rhetoric and his dennouncement of the political establishment and the media.

On Election Day 1988, the computer system used to count the votes shut down, as Cárdenas held an initial lead. That event is remembered by the phrase se cayó el sistema ("the system crashed"). When the system was restored, Carlos Salinas was declared the winner.[49] The expression "se cayó el sistema" became a euphemism for electoral fraud. All the opposition candidates refused to recognize the official results and claimed that a massive electoral fraud had been orchestrated by the government. Nevertheless, Salinas was confirmed by the Chamber of Deputies, controlled by the PRI, as the winner.

Post-presidency

[edit]Director of Fondo de Cultura Económica

[edit]After completing his term, he became the director of the Fondo de Cultura Económica (FCE) in 1990. He implanted modernization programs in production and administration. It incorporated the most advanced techniques in book publishing and graphic arts and maintained the openness and plurality features in the publication policy of the company.

On 4 September 1992, he inaugurated the new facilities, on 227 Picacho-Ajusco Road. Surrounded by garden and offices, it hosts cultural unity Jesús Silva Herzog, the Gonzalo Robles Library, which houses the growing publishing history of the Fund, and the seller Alfonso Reyes.

On the international scene in 1990, the existing facilities were remodeled subsidiaries. The presence of the Economic Culture Fund acquired a larger projection in the Americas: on 7 September 1990, the subsidiary in San Diego, California, was founded. On 21 June 1991 Seller Azteca opened its doors in São Paulo, Brazil. In 1994 FCE facilities were inaugurated in Venezuela, and in 1998, another subsidiary was established in Guatemala. This Thus, the FCE reached a significant presence in Latin America with nine subsidiaries: Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Chile, Spain, United States, Guatemala, Peru and Venezuela.

In publishing field, under his direction, 21 new collections were launched: in 1990, Keys (Argentina) in 1991, A la Orilla del Viento, Mexican Codices, University Science and Special Editions of At the Edge of the wind; in 1992, Breviary of Contemporary Science (Argentina) and New Economic Culture, in 1993 Library Prospective, Mexican Library, Library Cervantes Prize (Spain), and History of the Americas Trust and Cruises, in 1994, Word of Life and Indians A Vision of America and the Modernization of Mexico; Files, Sunstone (Peru), Entre Voces, Reading and Designated Fund 2000; Encounters (Peru) History of Mexico, and five periodicals: Galeras Fund, Periolibros, Images, Spaces for Reading and the Fund page.

During his administration, the FCE received several awards, among them: in 1992, FILIJ Book Award (CNCA) to children's books, in 1993 Golden Laurel Award (Department of Culture of the City of Madrid) in 1993, honorable mention Juan García Bacca (Peruvian Cultural Association) Award, and Gold Aztec Calendar (Mexican Association of Radio and Television). In 1994 and 1995 Award Book Bank of Venezuela for children's books.

The Spanish Council for Latin American Studies, distinguished him for his contributions to the development of reading in the Spanish language, received in 1997 the IUS Award by the Faculty of Law of the UNAM, and in 1998 the government of France awarded him the Academic Palms in rank of Commander for his contribution to cultural development. In 1999, Mr. De la Madrid received the medal Picasso Gold (UNESCO), for their work on the diffusion of Latin American culture.

Controversial statements

[edit]De la Madrid made headlines in May 2009 after a controversial interview with journalist Carmen Aristegui. During the interview, he said that his choice of Carlos Salinas de Gortari to succeed him in the Presidency had been a mistake and that he felt "very disappointed" in his successor, lamenting the widespread corruption of the Salinas administration. De la Madrid then directly accused Salinas of having stolen the money of the Presidential slush fund, and also accused his brother Raúl Salinas de Gortari of having ties to drug lords.[50][51]

Only two hours after the interview had been broadcast, a group of PRI leaders, including Emilio Gamboa Patrón, Ramón Aguirre, Francisco Rojas, and De la Madrid's sons Enrique and Federico, arrived at De la Madrid's home and reportedly asked him to retract his statements, arguing that they could damage the party. As a result, on the same day De la Madrid issued a statement retracting the comments he had made during the interview with Aristegui, claiming that due to his advanced age and his poor health, he was not able to "correctly process" the questions.[52][53]

Death

[edit]De la Madrid died on 1 April 2012, at 7:30 am in a Mexican hospital, following a lengthy hospitalization due to complications from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, which led to acute kidney injury and cardiac arrest.[54]

Public image and legacy

[edit]

Unlike his predecessors (specially Luis Echeverría and José López Portillo), President De la Madrid was noted for making relatively few speeches and keeping a more reserved and moderate public image. Although that has been attributed to a strategy to break with his predecessors' populist legacies, President De la Madrid's public image was considered "gray" by critics.[55] This perception worsened with his government's slow response to the 1985 Earthquake, when President De la Madrid also rejected International aid in the immediate aftermath of the tragedy.

President De la Madrid's biggest legacy may have been his implementation of economic neoliberal reforms in Mexico, breaking with decades of economic nationalism, and beginning mass privatization of state-run companies, a process which would be further deepened during the administration of his successor, Carlos Salinas de Gortari. De la Madrid was also the first of the so-called Technocrats to become president.[56] On the other hand, those reforms and his unwillingness to allow a primary election to choose the PRI candidate for the 1988 Presidential elections are credited as the factors which led to the split of the party in 1987, with Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas and Porfirio Muñoz Ledo founding the Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD by its initials in Spanish) in 1989, taking a great number of former priístas with them.

Under his "Moral Renovation" campaign, his administration attempted to fight corruption at all Government levels, fulfilling Mexico's foreign debt compromises, and creating the Secretaría de la Contraloría General de la Federación (Secretariat of the General Inspectorate of the Federation) to guarantee fiscal discipline and to keep an eye on possible corrupt officials. Nevertheless, his administration still had some corruption scandals of its own, the most notorious being the murder of journalist Manuel Buendía in 1984 by agents of the Federal Security Directorate (Buendía had been investigating possible ties between Drug cartels, the CIA and the FSD itself).[57] De la Madrid shut down the FSD in 1985, although in its place similar Intelligence agencies would be created in subsequent years.

Finally, his administration's handling of the 1986 elections in Chihuahua and, specially, the 1988 Presidential elections, remains highly controversial.

In a 1998 interview for a documentary produced by Clío TV about his administration, De la Madrid himself concluded:

"What hurts me the most, is that those years of economic adjustment and structural change, were also characterized by a deterioration of the income distribution, a depression of the real wages, and an insufficient creation of jobs. In summary, by a deterioration of the social conditions."[58]

In a national survey conducted in 2012, 36% of the respondents considered that the De la Madrid administration was "very good" or "good", 26% responded that it was an "average" administration, and 30% responded that it was a "very bad" or "bad" administration.[59]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Encyclopædia Britannica (2008). "Miguel de la Madrid". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 1 July 2008.

- ^ a b Ortiz de Zárate, Roberto (10 May 2007). "Miguel de la Madrid Hurtado" (in Spanish). Fundació CIDOB. Archived from the original on 20 May 2015. Retrieved 1 July 2008.

- ^ Zamora, Gerardo (July–September 1990). "La política laboral del Estado Mexicano: 1982-1988". Revista Mexicana de Sociología. 52 (3): 111–138. doi:10.2307/3540710. JSTOR 3540710.

- ^ Carlos Valdez Ramírez (19 August 2016). "Fuerte de carácter y muy íntegro Miguel de la Madrid (in Spanish, fifth paragraph)". El Noticiero. Retrieved 1 July 2017.

- ^ a b c "Muere Paloma Cordero, viuda del expresidente Miguel de la Madrid". El Financiero. 11 May 2020. Archived from the original on 18 May 2020. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- ^ Jorge G. Castañeda, Perpetuating Power, New York: The New Press 2000, pp. 45, 177

- ^ John W. Sherman, "Miguel de la Madrid" in Encyclopedia of Mexico. Fitzroy Dearborn 1997, p. 400.

- ^ Enrique Krauze, Mexico: Biography of Power. New York: HarperCollins 1997, p. 763.

- ^ Castañeda, Perpetuating Power, p. 178.

- ^ Duncan, Richard; Kelly, Harry (21 June 2005). "An Interview with Miguel de la Madrid". Time. Archived from the original on 21 December 2008. Retrieved 1 July 2008.

- ^ Rivera Ayala, Clara (2008). Historia de México II. Cengage Learning Editores. p. 381.

- ^ Camp, "the Time of the Technocrats and Deconstruction of the Revolution", pp. 613-14.

- ^ Roderic Ai Camp, "The Time of the Technocrats and Deconstruction of the Revolution" in The Oxford History of Mexico, Michael C. Meyer and William H. Beezley, eds. New York: Oxford University Press 2000, p.613.

- ^ Collado, Maria del Carmen (December 2011). "Autoritarismo en tiempos de crisis. Miguel de la Madrid 1982-1988". Historia y Grafía (37): 149–177. Retrieved 10 July 2018.

- ^ a b Fernandez Menendez, Jorge (1 June 1992). "Chihuahua otra vez". Retrieved 10 July 2018.

- ^ Fuentes Mares, Jose (1985). Historia ilustrada de México: De Hernán Cortés a Miguel de la Madrid. Océano. p. 467. ISBN 968-493-160-3.

- ^ Delgado de Cantú, Gloria M. (2003). México, estructuras política, económica y social. Pearson Educación. pp. 123–124.

- ^ Hurtado, Miguel de la Madrid; Nolan], [James (1982). "Miguel de la Madrid on Population Policy in Mexico". Population and Development Review. 8 (2): 435–438. doi:10.2307/1973019. JSTOR 1973019. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- ^ González de León Aguirre, Deyanira (Spring 1994). "El aborto y la salud de las mujeres en México". Salud Problema (25): 38. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- ^ Lamas, Marta (March–April 2009). "La despenalización del aborto en México". Nueva Sociedad (220). Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- ^ Brito Domínguez, Myriam (2001). "Abortion in Mexico, Year 2000" (PDF). Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- ^ "Molotov en Palacio Nacional". Milenio (in Spanish). 11 November 2014. Retrieved 14 October 2017.

- ^ Fabrizio Mejía Madrid, "Insurgentes" in The Mexico City Reader (University of Wisconsin Press, 2004), ed. Rubén Gallo, trans. Lorna Scott Fox & Rubén Gallo, p. 73.

- ^ Castigo al Pato: 23 años de cárcel y el pago del traje de Carrillo Castro, Proceso (30 August 1986).

- ^ Arturson, G. (April 1987). "The tragedy of San Juanico--the most severe LPG disaster in history". Burns Incl Therm Inj. 13 (2): 87–102. doi:10.1016/0305-4179(87)90096-9. PMID 3580941.

- ^ De Anda Torres, Abigaíl (2006). La reconstrucción de la identidad de San Juan Ixhuatepex, Tlalnepantla de Baz Estado de México, 1984-2006. Ensayo para obtener tesis, UNAM, México, 100pp.

- ^ "Suicidios in Tlatelolco:Sismo en Mexico" (in Spanish). Mexico City: La Prensa. 14 September 2005. p. 2.

- ^ Velasco Molina, Carlos (20 September 1985). "Estricto Patrullaje Militar Para Garantizar paz: Aguirre" (in Spanish). Mexico City: Excélsior. pp. 1a, 22a.

- ^ a b c Haber, Paul Lawrence (1995). "Earthquake of 1985". Concise Encyclopedia of Mexico. Taylor & Frances Ltd. pp. 179–184.

- ^ Kirkwood, Burton (2000). History of Mexico. Westport, CT, USA: Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. p. 203. ISBN 0-313-00243-6.

- ^ "El terremoto en Mexico de 1985" (in Spanish). Retrieved 4 October 2008.

- ^ "No queremos goles, queremos frijoles". El País (in Spanish). 8 May 1986. Retrieved 20 February 2018.

- ^ "INAUGURACION MUNDIAL "MÉXICO '86"... ABUCHEAN Y SE LA MIENTAN AL PRESIDENTE MIGUEL DE LA MADRID..." YouTube. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- ^ "LAS RECHIFLAS AL PRESIDENTE MARCARON LA INAUGURACION: AL SEGUNDO JUEGO ASISTIO SIGILOSAMENTE" (in Spanish). Proceso. 7 June 1986. Archived from the original on 13 June 2018. Retrieved 20 February 2018.

- ^ "HACE 25 AÑOS SE INAUGURÓ EL MUNDIAL DE MÉXICO 1986" (in Spanish). Record. 1 January 2013. Retrieved 20 February 2018.

- ^ ¿Por Qué Perdimos?: Reflexiones Desde El Anonimato De Un Ciudadano Sin Futuro (in Spanish). Palibrio. 12 March 2013. ISBN 9781463352714. Retrieved 20 February 2018.

- ^ Riding, Alan (25 June 1986). "MEXICANS, HURT IN THE OIL CRISIS, TURN THEIR ANGER ON DE LA MADRID". The New York Times. Retrieved 25 November 2021.

- ^ Foweraker, Joe (1990). Popular Movements and Political Change in Mexico. Lynne Rienner Publishers. p. 129.

- ^ Nadelman, Ethan A. Cops Across Borders: The Internationalization of U.S. Criminal Law Enforcement. University Park: Penn State Press 1993.

- ^ María Celia Toro. "Drug Trade" in Encyclopedia of Mexico. Fitzroy Dearborn 1997, pp. 419-20.

- ^ Weinstein, Henry (1 February 1990). "2 Ex-Officials in Mexico Indicted in Camarena Murder : Narcotics: One-time high-ranking lawmen are alleged to have participated in the 1985 slaying. So far, 19 people have been charged in the drug agent's death". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 15 April 2018. Retrieved 25 June 2018.

- ^ Rivera Ayala, Clara (2008). Historia de México II. Cengage Learning Editores. p. 387.

- ^ Levi, Isaac A. (4 April 1986). Mexican jet pilots claim plane crash caused by explosion. Kentucky New Era (AP).

- ^ "The Montreal Gazette - Google News Archive Search". news.google.com. Retrieved 8 January 2018.

- ^ "The Crash of Mexicana de Aviacion Flight 940". ecperez.blogspot.co.nz. 29 September 2009. Retrieved 8 January 2018.

- ^ Camp, "The Time of the Technocrats", p. 615.

- ^ a b c Delgado de Cantú, Gloria (2002). Historia de México, Volumen 2. Pearson Educación. ISBN 970-26-0356-0.

- ^ Werner, Michael. Concise Encyclopedia of Mexico. Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers.

- ^ "1988: La caída del sistema". CNN. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 26 October 2013.

- ^ Castillo, Eduardo (17 May 2009). "Ex-president of Mexico criticizes his successor, igniting scandal in PRI". The Morning Call. Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- ^ "La corrupción de Raúl Salinas, según el ex presidente De la Madrid". Aristegui Noticias (in Spanish). Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- ^ "Por miedo, Miguel de la Madrid se retractó de acusaciones contra CSG". La Jornada. 16 May 2009. Retrieved 11 August 2019.

- ^ "Las polémicas confesiones de Miguel de la Madrid Hurtado". SDP Noticias. April 2012. Retrieved 11 August 2019.

- ^ "Murió Miguel de la Madrid a causa de enfisema pulmonar". www.milenio.com. Archived from the original on 5 April 2012. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- ^ Montalvo, Tania (April 2012). "MIGUEL DE LA MADRID, EL PRESIDENTE DEL QUIEBRE PRIISTA". Retrieved 10 July 2018.

- ^ Granados, Omar. "¿Cómo fue el sexenio de Miguel de la Madrid?". Retrieved 10 July 2018.

- ^ Becerril, Andres. "El de Buendía, el primer crimen de narcopolítica". Excelsior. Retrieved 10 July 2018.

- ^ "Miguel de la Madrid - Oportunidades perdidas". Sexenios (in Spanish). Clío TV.

- ^ Beltran, Ulises (29 October 2012). "Zedillo y Fox los ex presidentes de México más reconocidos". Imagen Radio. Archived from the original on 26 January 2020. Retrieved 26 August 2023.

Further reading

[edit]- Castañeda, Jorge G. Perpetuating Power: How Mexican Presidents Were Chosen. New York: The New Press 2000. ISBN 1-56584-616-8

- Krauze, Enrique, Mexico: Biography of Power. New York: HarperCollins 1997. ISBN 0-06-016325-9

External links

[edit]- Biography by CIDOB (in Spanish)

- Miguel de la Madrid at Find a Grave

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- 20th-century presidents of Mexico

- Candidates in the 1982 Mexican presidential election

- Institutional Revolutionary Party politicians

- 20th-century Mexican lawyers

- 1934 births

- 2012 deaths

- National Autonomous University of Mexico alumni

- Academic staff of the National Autonomous University of Mexico

- Harvard Kennedy School alumni

- Politicians from Colima City

- Members of the Order of Jamaica

- Collars of the Order of Isabella the Catholic

- Grand Crosses with Diamonds of the Order of the Sun of Peru

- 20th-century Mexican politicians

- Neoliberalism

- Respiratory disease deaths in Mexico

- Deaths from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- Mexican Roman Catholics