Milwaukee Art Museum

The Museum's Quadracci Pavilion seen from the south | |

Interactive fullscreen map | |

| Established | 1888 |

|---|---|

| Location | 700 N. Art Museum Drive Milwaukee, Wisconsin |

| Coordinates | 43°2′24″N 87°53′49″W / 43.04000°N 87.89694°W |

| Type | Art museum |

| Collection size | 34,000 works |

| Visitors | 232,000 (2023)[1] |

| Director | Marcelle Polednik |

| Public transit access | |

| Website | www |

The Milwaukee Art Museum (also referred to as MAM) is an art museum in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Its collection of over 34,000 works of art and gallery spaces totaling 150,000 sq. ft. (13,900 m²) make it the largest art museum in the state of Wisconsin and one of the largest art museums in the United States.[1][2][3]

Location and visit

[edit]Located on the lakefront of Lake Michigan, the Milwaukee Art Museum is one of the largest art museums in the Midwestern United States. Aside from its galleries, the museum includes a cafe, named Cafe Calatrava, overlooking Lake Michigan, and a gift shop.[4]

Hours

[edit]Normal operating hours for MAM are Tuesday–Wednesday and Friday–Sunday 10:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m., Thursday 10:00 a.m. to 8:00 p.m.[4][5]

History

[edit]Origins to the 1960s

[edit]Beginning around 1870, multiple organizations were founded in order to bring an art gallery to Milwaukee, as the city was still a growing port town with few or no facilities to hold major art exhibitions. All attempts to build a major art gallery failed despite the presence of active art collectors in town, such as banker Alexander Mitchell, and manufacturers William Henry Metcalf and Charles Allis.[6][7]

In 1883, local businessman Frederick Layton, a British immigrant who made his fortune through wholesale, meatpacking, and railroad ventures in Wisconsin, suggested establishing an art gallery for the city of Milwaukee.[8] He commissioned Scottish architect George Ashdown Audsley, of the firm W. & G. Audsley, to design the building later known as the Layton Art Gallery. Erected at the corner of Mason and Jefferson streets, Audsley's Greek Revival-style, one-story building was inaugurated on April 5, 1888.[9] Layton provided a $100,000 endowment to the new gallery for the acquisition of artworks, while part of his own collection was put on display.[10] Wisconsin painters Edwin C. Eldridge and George Raab served as the gallery's first and second curators, respectively.[11]

-

Eastman Johnson, Frederick Layton, 1893

-

George Ashdown Audsley's design for the Layton Art Gallery, c. 1885

-

The Layton Art Gallery around the time of its opening

-

The Layton Art Gallery's salon-style hang as recreated at MAM, 2023

In parallel, the Milwaukee Art Association (later Milwaukee Art Society), created by a group of German panorama artists and local businessmen, disputed the claim to be the city's first art gallery, having also been established in 1888.[12] In 1911, it relocated to a new building adjacent to the Layton Art Gallery and eventually took on the name of Milwaukee Art Institute five years later. [13] The institute's collection consisted mostly of gifts and purchases from Wisconsin artists, as well as gifts from the personal collection of its first director, Samuel O. Buckner.

-

Lady in Black (1900) by Wisconsin painter Louis Mayer, gifted in 1913

-

Drawing in the Sand (c. 1911) by Spanish painter Joaquín Sorolla, gift from the Buckner collection in 1919

Following Frederick Layton's death, George Raab was replaced by artist and educator Charlotte Partridge as curator and director of the Layton Art Gallery in 1922.[11] Partridge had founded the Layton School of Art two years prior, and would continue to lead it along with her lifelong partner, art instructor Miriam Frink.[14] During her tenure, she focused on contemporary art exhibitions and acquisitions, and additionally served as director of the Federal Art Project for Wisconsin from 1935 to 1939, as part of the Works Progress Administration, a New Deal agency.[15] Meanwhile, the Milwaukee Art Institute came under the direction of German-born painter Alfred Pelikan in 1926, a position he occupied until 1942.[16]

In 1954, Partridge retired from the Layton Art Gallery, while Frink retired from the directorship of the Layton School of Art, where she was replaced by artist Edmund Lewandowski. Three years later, in 1957, the Milwaukee Art Institute and Layton Art Gallery merged their collections to form the Milwaukee Art Center, under the direction of art historian Edward H. Dwight.[17] The institution moved into the newly-built Eero Saarinen-designed Milwaukee County War Memorial.[18]

Kahler Building and growth of collections

[edit]

In 1975, Margaret (Peg) Bradley, the widow of industrialist Harry Lynde Bradley, donated an ensemble of more than 600 European and American Modern artworks to the museum. Highlights of the gift include Fauvist paintings, German Expressionist works by Wassily Kandinsky and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, as well as a group of works by Wisconsin-native Georgia O’Keeffe. The brutalist Kahler Building (1975) was designed by architect David Kahler in response to the donation to house the museum's new Bradley Wing, as well as other suites of galleries for the collection. Peg Bradley herself contributed $1 million to the construction of the addition.[2] In the wake of the Kahler expansion, the name of Milwaukee Art Museum was officially adopted by the institution in 1980.[13]

In 1999, the Milwaukee-based Chipstone Foundation established a partnership with the museum to display part of their collections of American decorative arts and furniture in dedicated galleries on a rotating basis.[19]

Quadracci Pavilion and further expansions (since 2001)

[edit]The Quadracci Pavilion is a multi-purpose 13,197-square-meter (142,050-square-foot) building with areas that include a reception hall, auditorium, exhibition space, and stores. It was designed by Spanish architect Santiago Calatrava and completed in 2001.[20] The construction method of concrete slabs into timber frames was revolutionary in architecture. Windover Hall is a 90-foot (27 m)-tall grand reception area topped with a glass roof. The style and symbolism of the building are based on Gothic architecture and designed to represent the shape of a ship looking over Lake Michigan. As Calatrava stated, “the building’s form is at once formal (completing the composition), functional (controlling the level of light), symbolic (opening to welcome visitors), and iconic (creating a memorable image for the Museum and the city).”[21]

The Quadracci Pavilion contains a movable, wing-like Burke brise soleil that opens up for a wingspan of 217 feet (66 m) during the day, folding over the tall, arched structure at night or during inclement weather. There are sensors on the wings that monitor wind speeds, so if the wind speeds are over 23 miles per hour (37 km/h) for over 3 seconds, the wings close. The pavilion received the 2004 Outstanding Structure Award from the International Association for Bridge and Structural Engineering.[22] This iconic building, often referred to as "the Calatrava", was previously used in the museum logo. The addition brought the total size of the museum to 341,000 square feet.[2]

-

Central vestibule of the Milwaukee Art Museum

-

Reiman Pedestrian Bridge, providing access to downtown Milwaukee

-

Milwaukee Art Museum with the Burke brise soleil closed

-

Windhover Hall and main entrance

-

Baumgartner Galleria

-

Schroeder Galleria and admissions desk

-

Windhover Hall windows overlooking Lake Michigan

The Cudahy Gardens were designed in conjunction with the Quadracci Pavilion by landscape architect Dan Kiley. This garden measures 600 feet by 100 feet, a rectangular shape that is divided into five lawns by a series of ten-foot-tall hedge lines. In this garden there is a center fountain that creates a 4-foot-tall water curtain. There are linden trees and crabapple trees scattered throughout this garden as well. The gardens were named after philanthropist Michael Cudahy, whose donations greatly contributed to their construction.[5]

The year 2001 saw the opening of the Herzfeld Photography, Print, and Drawing Study Center on the lower level of the Kahler Building, following a gift from the Milwaukee-based Richard and Ethel Herzfeld Foundation.[23] In 2004, the museum acquired close to 300 American and European works through the gift of the collection of Maurice and Esther Leah Ritz.[24]

In November 2015, the museum opened a $34 million expansion funded jointly by a museum capital campaign and by Milwaukee County.[25] The expansion was designed by Milwaukee architect James Shields and the HGA firm to provide additional gallery space, including a section devoted to light-based media, photography, and video installations.[26] The two-story building's total size is 120,000 sq. ft., including a new atrium and lakefront-facing entry point for visitors.[27][28] The design emerged after a lengthy process that included the main architect's temporary departure because of design disputes in 2014.[29]

In 2017, the museum grouped its George Peckham Miller Art Research Library (established in 1916), its institutional archives, and its manuscripts under a unique Milwaukee Art Museum Research Center, before relocating a majority of these collections to the historic Judge Jason Downer Mansion, in the neighborhood of Yankee Hill.[30] The house was built in the High Victorian Gothic style for lawyer and former Wisconsin Supreme Court justice Jason Downer in 1874. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1989, along with several properties, as part of the First Ward Triangle Historic District.[31]

In December 2017, the museum announced its purchase of nearby O'Donnell Park from Milwaukee County.[32] The institution had already commissioned the installation of The Calling, a public sculpture by American artist Mark di Suvero, on the site in 1982.[33] In 2023, the park was officially renamed Museum Center Park.[34]

Collection

[edit]The museum houses over 34,000 works of art, a selection of which is presented on four floors, with works from antiquity to the present. Included in the collection are 15th- to 20th-century European and 17th- to 20th-century American paintings, sculpture, prints, drawings, decorative arts, photographs, and folk and self-taught art. Among the best in the collection are the museum's holding of paintings by artists of the Ashcan School, American decorative arts, German Expressionism, folk and Haitian art, and American art after 1960.[35][36][37]

The museum holds one of the largest collections of works by Georgia O'Keeffe in the United States.[38][39][40] Other artists represented include Gustave Caillebotte, Nardo di Cione, Francisco de Zurbarán, Jean-Honoré Fragonard, Winslow Homer, Auguste Rodin, Edgar Degas, Claude Monet, Gabriele Münter, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Frank Lloyd Wright, Pablo Picasso, Joan Miró, Wassily Kandinsky, Mark Rothko, Robert Gober, and Andy Warhol.

It also has paintings by European painters Francesco Botticini, Jan Swart van Groningen, Ferdinand Bol, Jan van Goyen, Hendrick Van Vliet, Franz von Lenbach, Ferdinand Waldmüller, Carl Spitzweg, William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Jean-Léon Gérôme, Gustave Caillebotte, Camille Pissarro, Alfred Kowalski, Jules Bastien-Lepage, and Max Pechstein.[41][42][43][44][45][46][47][48][49][50]

Gallery

[edit]-

A Rus Kolty Pendant, 12th Century

-

Albert Bierstadt, Grizzly Bears, c. 1859

-

Robert S. Duncanson, Minneopa Falls, 1862

-

Carl Spitzweg, Scholar of Natural Sciences, 1875-80

-

Elihu Vedder, Star of Bethlehem, 1879-80

-

Winslow Homer, Hark! The Lark, 1882

-

Jean-Léon Gérôme, The Two Majesties (Les Deux Majestés), 1883

-

William Merritt Chase, Gathering Wild Flowers, c. 1895

-

Claude Monet, Waterloo Bridge, 1900

-

Frank Lloyd Wright, Tree of Life window, from the Darwin D. Martin House, in Buffalo, New York, 1904

-

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Dodo with a Feather Hat (Dodo mit Federhut), 1911

-

Tiffany & Co., Iris corsage ornament

-

Robert Henri, Chinese Lady, 1914

-

Georgia O'Keeffe, The Flag, 1918

-

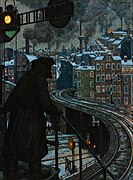

Hans Baluschek, City of Workers (or Working-Class City), 1920

-

Hovsep Pushman, The Incense Burner, before 1921

-

Andy Warhol, Campbell's Soup Cans, 1965

Governance

[edit]Management

[edit]Directors

- 1977–1985 Gerald Nordland

- 1985–2002 Russell Bowman[51]

- 2002–2008 David Gordon – director and CEO[52]

- 2008–2016 Daniel Keegan

- 2016– Marcelle Polednik – Donna and Donald Baumgartner director[53]

Funding

[edit]As of 2015, the museum’s endowment is around $65 million.[54] Endowment proceeds cover a fraction of the museum's expenses, leaving it overly dependent on funds from day-to-day operations such as ticket sales.[55] Daniel Keegan, who has served as the museum's director since 2008, negotiated an agreement with Milwaukee County and the Milwaukee County War Memorial for the long-term management and funding of the facilities in 2013.[56] In 2024, a $3.54 million gift helped establish an endowment to make admission to the museum free for children aged 12 and under.[57]

Controversy

[edit]In June 2015 the museum's display of a work depicting Benedict XVI, composed of 17,000 latex condoms, created outrage among Catholics and others.[58]

In popular culture

[edit]The Quadracci Pavilion makes an appearance in the 2008 EA racing video game Need for Speed: Undercover,[59] as well as the film Transformers: Dark of the Moon, where it stands for the headquarters of car collector Dylan Gould (played by actor Patrick Dempsey).[60][61]

The 2011 comedy film Bridesmaids, set in Milwaukee, features opening aerial shots of the museum.[62]

In 2020, the Quadracci Pavilion also featured in season 2, episode 11 of the comedy television series Joe Pera Talks with You, titled “Joe Pera Shows You How to Do Good Fashion”.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "Milwaukee Art Museum Annual Report 2023" (PDF). www.mam.org. Retrieved 2025-01-27.

- ^ a b c "History". www.mam.org. Retrieved 2025-01-23.

- ^ "Reimagined Milwaukee Art Museum". www.mam.org. Retrieved 2025-01-25.

- ^ a b "Milwaukee Art Museum – Museum Review". Condé Nast Traveler. Retrieved 2022-04-29.

- ^ a b Museum, Milwaukee Art. "Visit | Milwaukee Art Museum". mam.org. Retrieved 2022-04-29.

- ^ "Charles & Sarah". Charles Allis Art Museum. Retrieved 2025-01-27.

- ^ Mooney, Claudia (2013-04-16). "The Layton Art Collection—1888-2013, Part 1". www.mam.org. Retrieved 2025-01-27.

- ^ "Milwaukee Matters". The Weekly Wisconsin. June 27, 1883. p. 4.

- ^ Eastberg, John C.; Vogel, Eric (2013). Layton's Legacy: A Historic American Art Collection, 1888–2013. Milwaukee, WI: Layton Art Collection, Inc. p. 30.

- ^ "The Layton Art Gallery Open". The New York Times. April 6, 1888. p. 1. ISSN 0362-4331.

- ^ a b Merrill, Peter C. (1997). German-American Artists in Early Milwaukee: A Biographical Dictionary. Madison, WI: Max Kade Institute for German-American Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. p. xxii.

- ^ Barry Adams (29 November 2015). "On Wisconsin: Like its director, the Milwaukee Art Museum is transformed". Wisconsin State Journal. Retrieved 17 June 2017.

- ^ a b Schulze, Franz (2001). Building a Masterpiece: Milwaukee Art Museum. Easthampton, MA: Hudson Hills Press. pp. 11–13.

- ^ "Miriam Frink". Wisconsin LGBTQ History Project. Retrieved 2025-01-27.

- ^ "Miriam Frink & Charlotte Partridge". Wisconsin Historical Society. Retrieved 2025-01-27.

- ^ Levy, Hannah Heidi (2004). Famous Wisconsin Artists and Architects. Oregon, WI: Badger Books. p. 129.

- ^ "Edward H. Dwight Papers - Biographical Note". Archives of American Art. Retrieved 2025-01-27.

- ^ Lindsay, Georgia (2016). The User Perspective on Twenty-First-Century Art Museums. New York, NY: Routledge. p. 78.

- ^ Prown, Jonathan (2020-06-01). "A Brief History of the Chipstone Foundation". Chipstone Foundation. Retrieved 2025-01-27.

- ^ Rovito, Rich (2022-05-04). "Calatrava Revisits His Iconic Milwaukee Design, 20+ Years Later". Milwaukee Magazine. Retrieved 2024-11-12.

- ^ "Quadracci Pavilion". www.mam.org. Retrieved 2025-01-27.

- ^ "Milwaukee Art Museum Addition, Milwaukee, Wisconsin". International Association for Bridge and Structural Engineering. Archived from the original on February 28, 2018. Retrieved January 31, 2018.

- ^ Anderson, Lauren (2019-07-03). "Herzfeld Foundation Gives $3.5 Million to Milwaukee Art Museum's Photography Program". BizTimes. Retrieved 2025-01-28.

- ^ "The Maurice and Esther Leah Ritz Collection". www.mam.org. Retrieved 2025-01-27.

- ^ Kilmer, Graham (2015-11-16). "Milwaukee Art Museum Unveils New Addition". Urban Milwaukee. Retrieved 2025-01-28.

- ^ "New Building Opens at Milwaukee Art Museum". The New York Times. 2015-11-23. Retrieved 2025-01-28.

- ^ Schumacher, Mary Louise (2015-11-13). "Milwaukee Art Museum's New Lakefront Atrium a Gracious, Rugged Success". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Retrieved 2025-01-28.

- ^ "New Pathways Welcome, Engage, and Inspire". HGA. Retrieved 2025-01-27.

- ^ Murphy, Bruce (17 November 2015). "Still Controversy Over Art Museum Addition". Urban Milwaukee. Retrieved 24 November 2015.

- ^ Horne, Michael (2018-03-19). "Judge Jason Downer's Home Restored". Urban Milwaukee. Retrieved 2025-01-27.

- ^ Weisiger, Marsha Lee (2017). Buildings of Wisconsin. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press. p. 135.

- ^ Hess, Corrinne (2017-12-18). "Milwaukee Art Museum Takes Ownership of O'Donnell Park Property". BizTimes. Retrieved 2025-01-28.

- ^ Snyder, Molly (2019-09-30). "Milwaukee OG: "The Calling" AKA the Orange Sunburst Sculpture". OnMilwaukee. Retrieved 2025-01-28.

- ^ Sandler, Larry (2023-09-21). "O'Donnell Park Has a New Name, and No One Knows Why". Milwaukee Magazine. Retrieved 2025-01-28.

- ^ Sarah Hauer (17 February 2017). "Art museum's Haitian collection explores spirituality, history, daily life". Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel. Retrieved 16 June 2018.

- ^ "Milwaukee Art Museum". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved 16 June 2018.

- ^ Chris Foran (19 October 2016). "Dark shadows overtake Milwaukee Art Museum". Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel. Retrieved 16 June 2018.

- ^ Kate Silver (9 August 2017). "Things to do in Milwaukee". The Washington Post. Retrieved 16 June 2018.

- ^ Mary Bergin (6 December 2015). "Milwaukee Art Museum gets new look with $34 million overhaul". Eau Claire Leader-Telegram. Retrieved 16 June 2018.

- ^ Amy Bertrand (22 October 2017). "Milwaukee: More than just beer here". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Retrieved 16 June 2018.

- ^ Goldstein, Rosalie (1986). Guide to the permanent collection. Milwaukee: The Museum. p. 248.

- ^ "Triptych with Josiah and the Book of the Law, The Adoration of the Golden Calf and The Transfiguration of Christ and by anonymous artist of the 16th century Netherlands". RDK. 9 November 2015. Retrieved 28 June 2018.

- ^ D'Alessandro, Stephanie (2003). German Expressionist Prints: The Marcia Granvil Specks Collection. Milwaukee: Hudson Hills Press. p. 11. ISBN 0-944110-94-0.

- ^ The Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art. Cleveland: Cleveland Museum of Art. 1994. p. 15.

- ^ Mary Louis Schumacher (21 April 2014). "Milwaukee Public Library may sell famous 'Bookworm' painting by Carl Spitzweg". Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel. Retrieved 28 June 2018.

- ^ Lardinois, A. P. M. H. (2006). Land of Dreams: Greek and Latin Studies in Honour of A.H.M. Kessels. Michigan: Brill. p. 248. ISBN 9789004150614.

- ^ Cass, Jeff (2008). Romantic Border Crossings. Hampshire: Ashgate Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7546-6051-4.

- ^ Brodskaïa, Nathalia (2018). Gustave Caillebotte (1848-1894). Parkstone International. ISBN 9781683256939.

- ^ Sharp, William (1914), The Bay View Magazine, Volume 22, Detroit, MI: Bay View Reading Circle, p. 352

- ^ Morrison, John (2014). Painting Labour in Scotland and Europe, 1850-1900. London: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 9781472415196.

- ^ "Russell Bowman Fine Art, www.bowmanart.com". www.bowmanart.com.

- ^ "Milwaukee Art Museum | Pressroom". www.mam.org. 2007-02-19. Retrieved 2017-01-06.

- ^ "Milwaukee Art Museum Announces New Director". www.mam.org. 2016-05-17. Retrieved 2025-01-28.

- ^ Ted Loos (December 28, 2015), Milwaukee Art Museum Reinvigorates With Renovations The New York Times.

- ^ Mary Louise Schumacher (October 28, 2011), Milwaukee Art Museum expansion began under Bowman Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.

- ^ Mary Louise Schumacher (October 23, 2015), Dan Keegan to leave Milwaukee Art Museum in May Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.

- ^ Rich Rovito (2024-12-03). "A Donation Guarantees Admission for Children Will Be Free at Milwaukee Art Museum". Milwaukee Magazine. Retrieved 2025-01-27.

- ^ Johnson, Annysa (2015-06-29). "Milwaukee Art Museum's embrace of condom portrait of pope draws disgust". Jsonline.com. Retrieved 2017-01-06.

- ^ Need for Speed: Undercover (2008) Game Screenshot – Imgur, retrieved 2022-09-24

- ^ Miller, Anna. "11 of Milwaukee's Most Famous Filming Locations". Milwaukee Magazine. Retrieved 16 December 2024.

- ^ Tanzilo, Bobby. ""Transformers 3" lands in Milwaukee". On Milwaukee. Retrieved 16 December 2024.

- ^ Stephanie Harte (2014-09-16). "MKE Locations, Scenery Utilized in Well-known Films". MarquetteWire. Retrieved 2025-01-27.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Milwaukee Art Museum within Google Arts & Culture

- Milwaukee Art Museum on Atlas Obscura

Media related to Milwaukee Art Museum at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Milwaukee Art Museum at Wikimedia Commons

- 1882 establishments in Wisconsin

- Art museums and galleries established in 1882

- Art museums and galleries in Wisconsin

- Buildings and structures completed in 2001

- High-tech architecture

- Modernist architecture in Wisconsin

- Museums in Milwaukee

- Neo-futurist architecture

- Santiago Calatrava structures

- Tourist attractions in Milwaukee