Richard Nixon's resignation speech

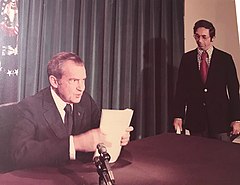

Nixon preparing to deliver the speech | |

| Date | August 8, 1974 |

|---|---|

| Time | 9:01 pm (Eastern Time, UTC-04:00) |

| Duration | 16 minutes |

| Venue | Oval Office, White House, Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Location | Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Cause | Watergate scandal |

| Participants | Richard Nixon |

| Watergate scandal |

|---|

|

| Events |

| People |

On August 8, 1974, U.S. President Richard Nixon delivered a nationally-televised speech to the American public from the Oval Office announcing his intention to resign the presidency the following day due to the Watergate scandal.

Nixon's resignation was the culmination of what he referred to in his speech as the "long and difficult period of Watergate", a 1970s federal political scandal stemming from the break-in of the Democratic National Committee (DNC) headquarters at the Watergate Office Building by five men during the 1972 presidential election and the Nixon administration's subsequent attempts to cover up its involvement in the crime. Nixon ultimately lost much of his popular and political support as a result of Watergate. At the time of his resignation the next day, Nixon faced almost certain impeachment and removal from office.[1]

According to his address, Nixon said he was resigning because "I have concluded that because of the Watergate matter I might not have the support of the Congress that I would consider necessary to back the very difficult decisions and carry out the duties of this office in the way the interests of the nation would require." Nixon also stated his hope that, by resigning, "I will have hastened the start of that process of healing which is so desperately needed in America." Nixon acknowledged that some of his judgments "were wrong," and he expressed contrition, saying: "I deeply regret any injuries that may have been done in the course of the events that led to this decision." He made no explicit mention, however, of the articles of impeachment pending against him.[2]

The following morning, August 9, Nixon submitted a signed letter of resignation to Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, becoming the only U.S. president to resign from office. Vice President Gerald Ford succeeded to the presidency upon Nixon's resignation.[3]

Background

[edit]On August 5, 1974, several of President Richard Nixon's taped Oval Office conversations were released. One of them, which was described as the "smoking gun" tape, was recorded soon after the Watergate break-in, and demonstrated that Richard Nixon had been told of the White House connection to the Watergate burglaries soon after they took place, and approved a plan to thwart the investigation into it. Nixon's popular and political support diminished substantially following the tapes' release.[4]

Nixon met with Republican congressional leaders two days later, on August 7, and was told that he would face certain impeachment in the House and subsequent removal from office in the Senate.

The evening of August 7, knowing that his presidency was effectively over, Nixon finalized his decision to resign.[5][6]

The president's speechwriter Raymond K. Price wrote the resignation speech.[5] It was delivered on the evening of August 8, 1974 from the Oval Office and was carried live on radio and television.[6]

Critical reaction and analysis

[edit]Jack Nelson of the Los Angeles Times wrote that Nixon's speech "chose to look ahead," rather than focus on his term.[7] This attribute of the speech coincides with John Poulakos's definition of sophistical rhetoric in Towards a Sophistic Definition of Rhetoric, because Nixon met the criterion of "[seeking] to capture what was possible"[8] instead of reflecting on his term.

In the British paper The Times the article Mr. Nixon resigns as President; On this day by Fred Emery took a more negative stance on the speech, characterizing Nixon's apology as "cursory" and attacking Nixon's definition of what it meant to serve a full presidential term. Emery suggests Nixon's definition of a full presidential term as "until the president loses support in Congress" implies that Nixon knew he would not win his impending impeachment trial and he was using this definition to quickly escape office.[9]

In his book Nixon: Ruin and Recovery 1973–1990, Stephen Ambrose finds that response from United States media to Nixon's speech was generally favorable. This book cites Roger Mudd of CBS News as an example of someone who disliked the speech. Mudd noted that Nixon re-framed his resignation speech to accent his accomplishments rather than to apologize for the Watergate scandal.[10]

In 1999, 137 scholars of American public address were asked to recommend speeches for inclusion on a list of "the 100 best American political speeches of the 20th century," based on "social and political impact, and rhetorical artistry." Nixon's resignation speech placed 39th on the list.[11]

Text

[edit]Good evening. This is the 37th time I have spoken to you from this office, where so many decisions have been made that shaped the history of this Nation. Each time I have done so to discuss with you some matter that I believe affected the national interest.

In all the decisions I have made in my public life, I have always tried to do what was best for the Nation. Throughout the long and difficult period of Watergate, I have felt it was my duty to persevere, to make every possible effort to complete the term of office to which you elected me.

In the past few days, however, it has become evident to me that I no longer have a strong enough political base in the Congress to justify continuing that effort. As long as there was such a base, I felt strongly that it was necessary to see the constitutional process through to its conclusion, that to do otherwise would be unfaithful to the spirit of that deliberately difficult process and a dangerously destabilizing precedent for the future.

But with the disappearance of that base, I now believe that the constitutional purpose has been served, and there is no longer a need for the process to be prolonged.

I would have preferred to carry through to the finish whatever the personal agony it would have involved, and my family unanimously urged me to do so. But the interest of the Nation must always come before any personal considerations.

From the discussions I have had with Congressional and other leaders, I have concluded that because of the Watergate matter I might not have the support of the Congress that I would consider necessary to back the very difficult decisions and carry out the duties of this office in the way the interests of the Nation would require.

I have never been a quitter. To leave office before my term is completed is abhorrent to every instinct in my body. But as President, I must put the interest of America first.

America needs a full-time President and a full-time Congress, particularly at this time with problems we face at home and abroad.

To continue to fight through the months ahead for my personal vindication would almost totally absorb the time and attention of both the President and the Congress in a period when our entire focus should be on the great issues of peace abroad and prosperity without inflation at home.

Therefore, I shall resign the Presidency effective at noon tomorrow. Vice President Ford will be sworn in as President at that hour in this office.

As I recall the high hopes for America with which we began this second term, I feel a great sadness that I will not be here in this office working on your behalf to achieve those hopes in the next 2 1/2 years. But in turning over direction of the Government to Vice President Ford, I know, as I told the Nation when I nominated him for that office 10 months ago, that the leadership of America will be in good hands.

In passing this office to the Vice President, I also do so with the profound sense of the weight of responsibility that will fall on his shoulders tomorrow and, therefore, of the understanding, the patience, the cooperation he will need from all Americans.

As he assumes that responsibility, he will deserve the help and the support of all of us. As we look to the future, the first essential is to begin healing the wounds of this Nation, to put the bitterness and divisions of the recent past behind us, and to rediscover those shared ideals that lie at the heart of our strength and unity as a great and as a free people.

By taking this action, I hope that I will have hastened the start of that process of healing which is so desperately needed in America.

I regret deeply any injuries that may have been done in the course of the events that led to this decision. I would say only that if some of my judgments were wrong, and some were wrong, they were made in what I believed at the time to be the best interest of the Nation.

To those who have stood with me during these past difficult months, to my family, my friends, to many others who joined in supporting my cause because they believed it was right, I will be eternally grateful for your support.

And to those who have not felt able to give me your support, let me say I leave with no bitterness toward those who have opposed me, because all of us, in the final analysis, have been concerned with the good of the country, however our judgments might differ.

So, let us all now join together in affirming that common commitment and in helping our new President succeed for the benefit of all Americans.

I shall leave this office with regret at not completing my term, but with gratitude for the privilege of serving as your President for the past 5 1/2 years. These years have been a momentous time in the history of our Nation and the world. They have been a time of achievement in which we can all be proud, achievements that represent the shared efforts of the Administration, the Congress, and the people.

But the challenges ahead are equally great, and they, too, will require the support and the efforts of the Congress and the people working in cooperation with the new Administration.

We have ended America's longest war, but in the work of securing a lasting peace in the world, the goals ahead are even more far-reaching and more difficult. We must complete a structure of peace so that it will be said of this generation, our generation of Americans, by the people of all nations, not only that we ended one war but that we prevented future wars.

We have unlocked the doors that for a quarter of a century stood between the United States and the People's Republic of China.

We must now ensure that the one quarter of the world's people who live in the People's Republic of China will be and remain not our enemies but our friends.

In the Middle East, 100 million people in the Arab countries, many of whom have considered us their enemy for nearly 20 years, now look on us as their friends. We must continue to build on that friendship so that peace can settle at last over the Middle East and so that the cradle of civilization will not become its grave.

Together with the Soviet Union we have made the crucial breakthroughs that have begun the process of limiting nuclear arms. But we must set as our goal not just limiting but reducing and finally destroying these terrible weapons so that they cannot destroy civilization and so that the threat of nuclear war will no longer hang over the world and the people.

We have opened the new relation with the Soviet Union. We must continue to develop and expand that new relationship so that the two strongest nations of the world will live together in cooperation rather than confrontation.

Around the world, in Asia, in Africa, in Latin America, in the Middle East, there are millions of people who live in terrible poverty, even starvation. We must keep as our goal turning away from production for war and expanding production for peace so that people everywhere on this earth can at last look forward in their children's time, if not in our own time, to having the necessities for a decent life.

Here in America, we are fortunate that most of our people have not only the blessings of liberty but also the means to live full and good and, by the world's standards, even abundant lives. We must press on, however, toward a goal of not only more and better jobs but of full opportunity for every American and of what we are striving so hard right now to achieve, prosperity without inflation.

For more than a quarter of a century in public life I have shared in the turbulent history of this era. I have fought for what I believed in. I have tried to the best of my ability to discharge those duties and meet those responsibilities that were entrusted to me.

Sometimes I have succeeded and sometimes I have failed, but always I have taken heart from what Theodore Roosevelt once said about the man in the arena, "whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood, who strives valiantly, who errs and comes short again and again because there is not effort without error and shortcoming, but who does actually strive to do the deed, who knows the great enthusiasms, the great devotions, who spends himself in a worthy cause, who at the best knows in the end the triumphs of high achievements and who at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly."

I pledge to you tonight that as long as I have a breath of life in my body, I shall continue in that spirit. I shall continue to work for the great causes to which I have been dedicated throughout my years as a Congressman, a Senator, a Vice President, and President, the cause of peace not just for America but among all nations, prosperity, justice, and opportunity for all of our people.

There is one cause above all to which I have been devoted and to which I shall always be devoted for as long as I live.

When I first took the oath of office as President 5 1/2 years ago, I made this sacred commitment, to "consecrate my office, my energies, and all the wisdom I can summon to the cause of peace among nations."

I have done my very best in all the days since to be true to that pledge. As a result of these efforts, I am confident that the world is a safer place today, not only for the people of America but for the people of all nations, and that all of our children have a better chance than before of living in peace rather than dying in war.

This, more than anything, is what I hoped to achieve when I sought the Presidency. This, more than anything, is what I hope will be my legacy to you, to our country, as I leave the Presidency.

To have served in this office is to have felt a very personal sense of kinship with each and every American. In leaving it, I do so with this prayer: May God's grace be with you in all the days ahead.[12]

Aftermath

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Wertheimer, Linda (August 8, 2014). "Remembering The Emotional Fallout From Nixon's Resignation". Morning Edition. NPR. Retrieved January 2, 2020.

- ^ "Nixon Resigns". The Washington Post. The Watergate Story. Archived from the original on November 25, 2016. Retrieved January 2, 2020.

- ^ "News Summary and Index Saturday, August 10, 1974: The presidency". The New York Times. August 10, 1974. Retrieved January 2, 2020.

- ^ Schmidt, Steffen W. (2013), American Government and Politics Today, 2013–2014 Edition, Wadsworth Publishing, p. 181, ISBN 978-1133602132,

In 1974, President Richard Nixon resigned in the wake of a scandal when it was obvious that public opinion no longer supported him.

- ^ a b Herbers, John (August 8, 1974). "Nixon Resigns". The New York Times. New York, New York. Archived from the original on July 14, 2017. Retrieved March 3, 2017.

- ^ a b Klein, Christopher (August 8, 2014). "The Last Hours of the Nixon Presidency, 40 Years Ago". History in the Headlines. New York: A&E Networks. Retrieved June 22, 2017.

- ^ Nelson, Jack (August 9, 1974). "Nixon Resigns in 'Interests of Nation': Cites His Achievements for Peace as His Legacy". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles. ProQuest 157487215.

- ^ Poulakos, John (1983). "Towards a Sophistic Definition of Rhetoric". Philosophy and Rhetoric. 16: 35.

- ^ Emery, Fred (August 9, 1999). "Nixon Resigns in 'Interests of Nation': Cites His Achievements for Peace as His Legacy". The Times. London, England: Times Newspapers. ProQuest 157487215.

- ^ Ambrose, Stephen E. (1991). Nixon: Ruin and Recovery 1973–1990. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-69188-2.

- ^ "Top 100 Speeches". americanrhetoric.com. Retrieved January 3, 2020.

- ^ Nixon, Richard (August 8, 1974). – via Wikisource.