Pegida

Patriotische Europäer gegen die Islamisierung des Abendlandes | |

| |

| Abbreviation | Pegida |

|---|---|

| Formation | 11 October 2014[4] |

| Legal status | Eingetragener Verein[5] (registered voluntary association) |

| Purpose | |

| Location |

|

Official language | German |

Chair | Lutz Bachmann |

Patriotic Europeans Against the Islamisation of the West[1][6][3] (German: Patriotische Europäer gegen die Islamisierung des Abendlandes), abbreviated Pegida (German: [peˈɡiːda], stylised in its logo as PEGIDA), is a German, anti-Islam, far-right extremist political movement.[7][8] Pegida believes that Germany is being increasingly Islamicised.[9]

Pegida wants to curb immigration into Germany and it accuses the authorities of failure to enforce related laws.[10] Pegida has held many demonstrations, often accompanied by counter-demonstrations.[11] In 2015, Lutz Bachmann, the founder of Pegida, resigned from the movement after a doctored photograph appeared where he appeared to be posing as Adolf Hitler and making racist statements on Facebook.[12] He was later reinstated.[13]

Though nationalism is a central feature, Pegida offshoots have formed in various countries. It is a grassroots part of the counter-jihad movement.[14]

History

[edit]Origin

[edit]

Pegida was founded in October 2014 by Lutz Bachmann, who runs a public relations agency in Dresden.[18] Bachmann's impetus for starting Pegida was witnessing a rally by alleged supporters of the Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK) against the siege of Kobani by the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) on 10 October 2014 in Dresden,[19] which he posted on YouTube on the same day.[20] The next day he founded a Facebook group called Patriotische Europäer Gegen die Islamisierung des Abendlandes ('Patriotic Europeans against Islamisation of the Occident').[9][21]

On 7 October, Yazidis and Muslim Chechens had violently clashed in Celle.[22] On 26 October, out of 5,000 protesters, "at least 400 right-wing extremists went on a rampage in downtown Cologne during a demonstration" by "Hooligans Against Salafists".[9] Bachmann mentioned these events in a release for his first demonstration.[23]

First wave of demonstrations

[edit]The first demonstration, or "evening stroll" (according to Pegida),[7] took place on 20 October 2014, and attracted only a handful of people.[9][24] During the following days, the movement began gaining wider public attention, and, subsequently, the weekly Monday demonstrations drew larger numbers of people. Among the 7,500 participants on 1 December 2014, the police identified 80 to 120 hooligans. The demonstration grew to 10,000 people on 8 December 2014.[24][25]

During the weekly demonstrations on Monday evenings, Pegida supporters carried banners with slogans such as "For the preservation of our culture", "Against religious fanaticism, against any kind of radicalism, together without violence" and "Against religious wars on German soil".[26]

On 19 December 2014, PEGIDA e.V. was legally registered in Dresden under the registration ID VR 7750,[27] with Bachmann as chairman, Rene Jahn as vice-chairman and Kathrin Oertel as treasurer. Pegida also formally applied for the status of a nonprofit organization.[28]

Aftermath of Charlie Hebdo shooting and rising tensions

[edit]

While the demonstration on 29 December 2014 was cancelled by the organizers, the movement continued to draw large numbers of participants in early January 2015. After the Charlie Hebdo shooting on 7 January 2015 in Paris, politicians (including ministers Thomas de Maizière and Heiko Maas) warned Pegida against misusing the attack on Charlie Hebdo for its own political agenda. On Saturday 10 January 2015 some 35,000[29] anti-Pegida protesters gathered to mourn the victims of Paris, observing a minute's silence in front of the Frauenkirche.

On 12 January 2015, Pegida organizers organised a rally of some 25,000 participants. Pegida's main organizer, Bachmann, declared the six central political objectives of Pegida, which include calls for selective immigration and the expulsion of religious extremists, the right and duty to integrate, and tighter internal security.[30]

On 15 January 2015, a young Eritrean immigrant, Khaled Idris Bahray, was found stabbed to death in his Dresden high-rise apartment. International media correspondents portrayed an "atmosphere of hatred and resentment" and published social media comments of Pegida sympathizers, who had expressed disdain for the dead Eritrean. Pegida's organizers rejected any possible connection.[31] One week later, the police investigation led to the arrest and eventual conviction of one of the victim's Eritrean housemates.[32][33]

Dresden police did not permit the demonstration planned for 19 January 2015, due to a definite threat against one of Pegida's leadership members in form of an Arabic-language tweet labelling Pegida an "enemy of Islam".[34] Pegida cancelled its 13th demonstration and stated in a post on its Facebook page that there was an explicit threat against a leadership member, and "his execution had been ordered by ISIS terrorists".[35]

Resignations

[edit]On 21 January 2015, Bachmann resigned from his position in Pegida after coming under fire for a number of Facebook posts.[36] Excerpts from a closed Facebook conversation incriminated Bachmann as having referred to immigrants with the insults "animals", "scumbags"[37] and "trash",[38] which are classified as hate speech in Germany. He was also quoted as commenting that extra security was needed at the welfare office "to protect employees from the animals".[39] A self-portrait of Bachmann allegedly posing as a reincarnation of Adolf Hitler, titled "He's back!" (which the Sächsische Zeitung later discovered to be a forgery, reporting that the moustache was added after the photo was taken),[13] went viral on social media[38] and was printed on front pages worldwide. On another occasion, Bachmann had posted a photo of a man wearing the uniform of the US white supremacist organisation Ku Klux Klan accompanied by the slogan: "Three Ks a day keeps the minorities away".[36] The Dresden state prosecutors opened an investigation for suspected Volksverhetzung (incitement to hatred), and Deputy Chancellor Sigmar Gabriel said the real face of Pegida had been exposed: "Anyone who puts on a Hitler disguise is either an idiot or a Nazi. People should think carefully about running after a pied piper like this".[39]

Der Spiegel reported that Pegida's media spokeswoman, Kathrin Oertel, turned to the Alternative for Germany (German: Alternative für Deutschland, AfD) for advice, and that the Sächsische Zeitung and Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung both confirmed there was a phone conversation between the AfD's Frauke Petry and Oertel. Petry said to Oertel that Bachmann should no longer be supported ("Ich habe ihr gesagt, dass Bachmann nicht mehr zu halten ist"). On that same day Oertel announced Bachmann's resignation.[40]

On 28 January, Oertel resigned as well, citing "the massive hostility, threats and career disadvantages" as the reason.[41] At the same time four other leading figures of Pegida stepped back.[42] On 2 February 2015 Oertel and six other former Pegida members founded Direkte Demokratie für Europa ('Direct Democracy for Europe') to distance themselves from the far-right tendencies of Pegida.[43]

Reinstatement

[edit]In February 2015, Pegida confirmed on its Facebook page that Lutz Bachmann had been re-elected as chairman by the six other members of the organisation's leadership committee, after the Sächsische Zeitung published a report that the Hitler moustache on the now infamous photo had been added after the photo was taken.[13]

Dresden mayoral election, 2015

[edit]In June 2015, following the resignation of CDU incumbent Helma Orosz on health grounds, Tatjana Festerling, who was dismissed from Pegida's leadership circle in June 2016,[44] ran for the mayoral office of Dresden, polling 9.6% in the first round with support from the far-right National Democratic Party of Germany (NPD).[45] On 7 July 2015, Bachmann announced that Pegida would participate in all future federal elections in Germany.[46]

Renewed protests

[edit]

The European migrant crisis revived the movement, which drew as many as 20,000 supporters to a 19 October 2015 rally in Dresden.[47][48] At the same time, observers perceived a further radicalisation of the crowd.[49]

On 28 September, two journalists were injured when Pegida participants kicked a local newspaper reporter and punched another TV reporter in the face.[50] On 12 October, Pegida demonstrators carried a mock gallows showing nooses reserved for Chancellor Angela Merkel and her deputy Sigmar Gabriel.[51] Bachmann derided the demonstrators who made it, calling it a "laughable piece of work with spelling errors" ("lächerliche Bastelarbeit mit Schreibfehlern"), a reference to the fact that the name Sigmar had been written with an "ie" (Siegmar).[52]

At Pegida's anniversary event on 19 October 2015, keynote speaker Akif Pirinçci named the Muslim refugees as invaders, with Germany becoming a "Muslim garbage dump".[53] Pirinçci said that politicians were acting like "Gauleiter against their own people",[54] as they wanted critics of Germany's refugee policy to leave the country. Addressing the crowd shouting "Resistance!", he claimed that the majority of Germans were held in contempt by the political class and that politicians wished that there were "other alternatives [to fight Pegida supporters[55]] – but the concentration camps are unfortunately out of order at the moment".[56] The crowd applauded and laughed, and let him continue his speech for another 20 minutes before calling upon him to finish.[57]

When 1,500 to 2,000 people celebrated Pegida in Leipzig's first anniversary, dozens of hooligans protested, vandalizing foreign-owned shops. Over 100 people were arrested. Mayor Burkhard Jung called it "open street terror".[58]

Party founding

[edit]The founder of Pegida, Lutz Bachmann, has set up a new political party, the Freiheitlich Direktdemokratische Volkspartei ("Liberal Direct Democratic People's Party", or FDDV). The FDDV was established on 13 June 2016.[59] Tommy Robinson founded a branch of Pegida in the United Kingdom.[60]

Position paper

[edit]

At the beginning of December 2014, Pegida published an undated and anonymous one-page manifesto of 19 bulleted position statements.[61]

Pegida's specific demands were initially unclear, largely because Pegida has refused a dialogue, considering the press to be a politically correct conspiracy.[62] Demonstrators have been observed chanting Lügenpresse (lying press), a term that has a long history in German politics.[63]

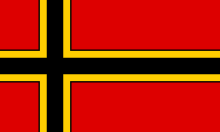

Alongside the German national flag, supporters of the movement have often been seen with a variant of the "Wirmer flag", a flag proposed by resistance member Josef Wirmer in 1944 for use after World War II.[64][65][note 1]

According to a Deutsche Welle report from December 2014, Pegida considers Islamism a misogynist and violent ideology.[69][70] In January 2015 The Guardian described Pegida as a far-right movement,[7] The New York Times labelled Pegida as anti-immigrant, and Angela Merkel has repeatedly questioned the motives underlying its anti-immigrant message.[7][71]

The State Authority for the Protection of the Constitution (German: Landesamt für Verfassungsschutz) of Thuringia considers Sügida (the regional Pegida branch of South Thuringia) to be steered by right-wing nationalists.[72]

In February 2015 the 19 positions were revised and broken down to the ten "Theses of Dresden".[73][74][75]

On 10 September 2015, Pegida demanded ten changes to the German refugee policy. They called for an immediate stop for asylum seekers and for a German 'asylum-emergency law'.[citation needed]

Participants and supporters

[edit]| Date | participants per day |

|---|---|

| 20 October 2014 | |

| 27 October 2014 | |

| 3 November 2014 | |

| 10 November 2014 | |

| 17 November 2014 | |

| 24 November 2014 | |

| 1 December 2014 | |

| 8 December 2014 | |

| 15 December 2014 | |

| 22 December 2014 | |

| 5 January 2015 | |

| 12 January 2015 | |

| 25 January 2015 | |

| 9 February 2015 | |

| 16 February 2015 | |

| 23 February 2015 | |

| 2 March 2015 | |

| 9 March 2015 | |

| 16 March 2015 | |

| 23 March 2014 | |

| 30 March 2015 | |

| 6 April 2015 | |

| 13 April 2015 | |

| 11 May 2015 | |

| 18 May 2015 | |

| 25 May 2015 | |

| 1 June 2015 |

According to Frank Richter, director of Saxony's Federal Agency for Civic Education, Pegida is "a mixed group—known figures from the National Democratic Party of Germany, soccer hooligans, but also a sizable number of ordinary citizens".[24] Werner Schiffauer, director of the Migration Council, has pointed out that the movement is strongest where people have hardly any experience with foreigners, and among "easterners who never really arrived in the Federal Republic and who now feel they have no voice".[62]

In December, Gordian Meyer-Plath, president of Saxony's State Authority for the Protection of the Constitution, said that initial suspicion that Pegida might tie in with the riots staged by Hogesa earlier in Cologne were not substantiated, so the movement was not put under official surveillance. He said there were no indications that the organizers were embracing right-wingers. This assessment was contested by the weekly Die Zeit who researched the ideological proximity of Pegida organizer Siegfried Däbritz to the German Defence League or the European Identitarian movement.[103] In a Tagesspiegel interview on 19 January, Meyer-Plath reaffirmed that the participant spectrum was very diverse and that there was no evidence of radicalisation.[104]

Dresden University of Technology (TU) interviewed 400 Pegida demonstrators on 22 December 2014 and 12 January 2015. According to the poll, the main reasons of their participation were dissatisfaction with the political situation (54 percent), "Islam, Islamism and Islamisation" (23 percent), criticism of the media and the public (20 percent), and reservations regarding asylum seekers and migrants (15 percent). In all, 42 percent had reservations regarding Muslims or Islam, 20 percent were concerned about a 'high rate of crimes' committed by asylum seekers, or feared socio-economic disadvantages.[105] The author, Vorländer, did not see Pegida as a movement of right-wing extremists, pensioners or the unemployed, but stated that the rallies served as a way to express feelings and resentments against a political and opinion-making elite which have not been publicly articulated before.[106]

A group of social scientists led by Dieter Rucht from the Social Science Research Centre of Berlin (Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung, WZB) collected data both by flyer and online survey. Despite a participation rate of only 18 percent in the online survey, it largely had similar results to the survey in Dresden. According to data from the WZB, Pegida was a male-dominated group, participants were mostly employees with a relatively high level of education, they had no confidence in institutions and they sympathised with AfD. In some cases the participants demonstrated far-right and right-wing extremist attitudes. The conclusion emphasised that Pegida supporters cannot be viewed as 'ordinary citizens', since they articulate group-focused enmity and racism.[107][108][109]

As of January 2016[update] on Facebook, the Pegida fan page had about 200,000 supporters.[110] According to political consultant Martin Fuchs, the fanpage allows the users there to present and more easily spread their ideas, which are not represented in the mainstream media.[111]

In December 2014, representatives of the NPD encouraged people to participate in Pegida rallies,[112] as did the German Defence League and the internet blog Politically Incorrect in an uploaded 'propaganda clip'.[113] According to the police, a few hundred "violent hooligans" have been participating in the Dresden rallies since December 2014.[114] The journalist Felix Menzel supports Pegida with his new right youth magazine Blaue Narzisse.[115]

Reactions

[edit]Counterdemonstrations

[edit]

Numerous protests against Pegida and affiliated movements in cities across Germany have drawn up to 35,000 demonstrators in Dresden[116][117] and up to 100,000 nationwide in January 2015, considerably more than Pegida's own concurrent demonstrations.[118]

In protest against a Pegida march, the floodlights of the Catholic Cologne Cathedral were switched off on the evening of 5 January 2015.[119] Dresden's Volkswagen plant used the same method of protest.[120]

German tabloid newspaper Bild launched a petition against Pegida, including former Chancellors Helmut Schmidt and Gerhard Schröder, as well as actress Karoline Herfurth and former footballer Oliver Bierhoff.[120]

Polls

[edit]According to a survey by the Emnid institute conducted in December 2014, 53% of East Germans and 48% of West Germans showed understanding for Pegida demonstrations. Differentiated by political parties, supporters consisted of 86% of all surveyed AfD members, 54% of all CDU members, 46% of all SPD members and 19% of all questioned supporters of The Left and Alliance '90/The Greens respectively.[121] 43% of all Germans participating in the survey thought that Pegida protesters are mainly concerned about the "spread of Islam". 33% believed that mainly right wing extremists attend their demonstrations.[122]

On behalf of German newspaper Die Zeit, YouGov conducted a survey from 12 to 15 December 2014. The survey showed that 30% of all 1107 surveyed felt sympathetic with regards to the demonstrations. Another 19% said they were understanding rather than the opposite. 26% approved at least partially of the demonstrations, while 10% showed little sympathy and a further 13% no understanding at all.[123]

A survey by TNS Infratest conducted in December 2014 on behalf of German magazine Der Spiegel showed that 65% of all surveyed German citizens felt that the government did not respond appropriately to their concerns about asylum policy and immigration. 28% disagreed, while 34% observed an increasing Islamisation in Germany.[124]

A representative survey by Emnid conducted from 17 to 18 December 2014 showed that 85% of all 1006 surveyed were not willing to participate in demonstrations for Pegida policy. Only 9%, more than half of all surveyed AfD followers, said they were in fact willing to demonstrate.[125]

On 18 December 2014, the Forsa Institute conducted a survey which showed that 67% of all surveyed Germans considered the danger of Islamisation exaggerated. 29%, consisting of 71% of all surveyed AfD supporters, felt too strong an Islamic influence in Germany and deemed respective demonstrations justified. 13% said they would participate in protests near their residence. 10%, consisting of 57% of all surveyed AfD followers, would even vote for an anti-Islamic party.[126]

A special report by the Bertelsmann Foundation, complemented by a TNS Emnid survey from November 2014, showed that a majority of German citizens considered Islam dangerous. Consequently, there seemed to be a "strong sympathy" for "Pegida slogans". In absolute numbers, 57% of all surveyed thought of Islam as a danger. 40% felt like "foreigners in their own country", while 24% stated that they would like to prevent further Muslim immigration. These opinions were not exclusive to any political camps or social classes.[127]

Political opponents

[edit]Former chancellor Angela Merkel criticised Pegida, saying that the leaders of Pegida "have prejudice, coldness, even hatred in their hearts".[128] The Federal Minister of the Interior Thomas de Maizière said that among the participants of the mass rallies were many ordinary people who expressed their concerns about the challenges of today's society.[129] Bernd Lucke, the leader of the political party Alliance for Progress and Renewal, has said he considers most of the positions of Pegida to be legitimate.[130] According to Lucke, the people taking part in these demonstrations did not feel that their concerns were being understood by politicians.[131] Similarly, the Dresden city council's AfD faction welcomed Pegida's weekly demonstrations.[132]

Josef Schuster, chairman of the Central Council of Jews in Germany, voiced his opposition to the group, saying that the possibility of an Islamic conquest of Germany would be as "absurd" as a resurrection of the Nazi regime. Schuster described Pegida as being "highly dangerous": "It starts with verbal assault and leads to actual attacks like the one on a planned refugee hostel in Bavaria". He referred to an arson attack on a home for asylum-seekers that was ready for occupation. After the attack, swastika graffiti was found at the scene. Schuster said that Pegida is a combination of "neo-Nazis, far-right parties and citizens who think they are finally allowed to show their racism and xenophobia openly". He condemned the movement, stating that the fear of Islamist terror was being exploited to disparage an entire religion.[133]

Aiman Mazyek from the Central Council of Muslims in Germany stated that again and again right-wing extremists gave the public the false impression of a racist Germany. The slogans of the protesters showed that xenophobia and anti-Semitic racism had become socially acceptable.[contradictory][citation needed]

Pegida has been criticised by Lutheran clergy, including the Bishop of Hamburg Kirsten Fehrs.[134]

Bachmann's credibility as a leader has been criticised because he has numerous criminal convictions, including "16 burglaries, drink-driving or driving without a licence and even dealing in cocaine".[24] In 1998 he fled to South Africa to avoid German justice, but was finally extradited and served his two-year jail sentence.[7][135]

In November 2014, Saxony's Interior Minister, Markus Ulbig (CDU), claimed that foreign criminals stayed in Germany too long. He announced the creation of a special police unit to deal with criminal immigrants in Dresden and the rest of Saxony. Investigators and specialists in criminal and immigrant law would collaborate to process foreign criminals in the criminal justice system, and prevent those not eligible for asylum from obtaining the right to stay in Germany.[136] Ulbig admitted that there had been a number of criminal acts committed by immigrants near the homes for asylum-seekers, but these were a minority and should not be allowed to undermine solidarity with the great majority of law-abiding refugees. He said police worked on criminal immigrant cases too slowly.[137]

On the night of 5 January 2015, the lights illuminating the Brandenburg Gate were completely turned off in protest against the Berlin offshoot named Bärgida[138][139] and also the lights of the Catholic cathedral Kölner Dom in Cologne in repudiation against Kögida.[140] The exterior lighting of the Semperoper in Dresden was also kept dark during the weekly Pegida marches. Both rallies in Berlin and Cologne were successfully blocked and disbanded by counter-demonstrations.[141]

On 26 January 2015 the US Overseas Security Advisory Council published an online security message entitled "Demonstration Notice Riots/Civil Unrest", stating U.S. citizens in Berlin, Frankfurt and Munich may "encounter Pegida and counter-Pegida demonstrations" on 26 January and 16 February 2015 in Düsseldorf, and "should avoid areas of demonstrations".[142]

Reactions from political scientists

[edit]Political scientist Werner J. Patzelt[143] from Dresden believes that politicians are "clueless" when it comes to dealing with Pegida. He says that this points to a serious problem in society, which neither the left wing nor parties of the political middle ground concern themselves with. This allows new social initiatives critical of Islam and immigrants to form.[144] According to him, the demonstrators are normal people approachable by the CDU, if only the party stopped following ostrich policy concerning immigration.[145]

Far-right politics expert Hans-Gerd Jaschke thinks that the demands in Pegida's position paper stem from the middle class centre-right and could as well be the content of CDU/CSU's position papers.[146] Social psychologist Andreas Zick from the Institute for Interdisciplinary Research on Conflict and Violence (IKG) assesses the party as a "middle-class right-wing populist movement".[146]

According to right-wing extremism researcher Johannes Kies, Pegida states what many people think.[147] Kies says that these opinions are widespread in society and that great anti-democratic potential is erupting there.[148] According to political scientist Alexander Häusler Germany is facing "a right-wing oriented group of enraged citizens" that "mingles with members of the right-wing scene and even hooligans".[149] Political scientist Hajo Funke sees a connection between Pegida and the great increase in attacks on asylum seekers in 2014. He says that because politics did not react to the population's fear of ever-increasing numbers of asylum seekers, these groups could use these fears and fan them further.[150]

In his article for the German newspaper Zeit Online, political scientist and historian Michael Lühmann called it "cynical to want to place Pegida in the tradition of 1989". The demonstrators in Dresden do not align themselves with the philosophy of the extreme right-wing, he says, but they fit the bill for "extremism of the centre ground", which is widespread in Saxony and for whose "group-based misanthropy ... at times the CDU, but prevalently the NPD and as of now the AfD stand" in parliament.[151]

In a similar fashion, historian Götz Aly traces the fact that Pegida were able to form in Dresden back to the city's history. In one of his columns in the Berliner Zeitung he referred to the Jewish emancipation of 19th century Saxony, where the comparatively few resident Jews were faced with unequally difficult legal obstacles. Aly concluded that in Dresden "freedom, self-aggrandising local presumption and fear of foreigners" have long belonged together.[152]

Political philosopher Jürgen Manemann considers Pegida an anti-political movement. According to Manemann, political action serves the common good and thus requires politicians to voice especially the interests of minorities. While politics was based on pluralism, Pegida was in fact anti-pluralistic and thus anti-political. In Manemann's eyes, the movement has neither an appreciation of otherness nor empathy, which he sees as the basic virtue of political action.[153]

Explaining especially those protests against the actually non-existent threat of Islamisation from people with middle-class backgrounds, political scientist Gesine Schwan referred to results from studies on prejudice. These studies indicate that aggressive prejudices do not originate from those groups met with resentment, but are rather a result of the situation of those who have them. In addition, fear of social decline often seems to be expressed through aggression. This is then directed especially against those minorities which may seem dangerous, but are in reality unable to defend themselves, often due to a perceived unpopularity within the respective society. In the first half of the 20th century, it was the Jewish minority who were imputed with plans for world domination. Today, it is the Muslim minority who is accused of plotting an Islamisation of Europe.[154]

In an interview about Pegida, researcher on prejudice Wolfgang Benz referred to his previous warnings about right-wing extremists using the fear of foreign infiltration for their ends. It was not the formation but the attendance figures that really surprised him.[155]

Political scientist and researcher on extremism Armin Pfahl-Traughber considers Pegida demonstrations "a new phenomenon of xenophobia".[156] In an interview, he accused Pegida leaders of fuelling "hostility and hatred against people of different ethnicity or religion".[157]

On 5 January 2015, the Council on Migration called for a new general orientation in German society. Since, in their eyes, migration was controllable only to a limited extent, they suggested an orientation committee. Consisting of politicians and representatives of immigrants and minorities, this would work together in order to analyse and redefine "German identity and solidarity in a pluralist republican society". Their results were to be included in German schools' curricula in order to emphasize the historical importance of migration in Germany. In the eyes of the council, German policy has been influenced for far too long by the CDU's guiding principle of "Germany not being a land of immigration". Thus, a concept of integration should include foreigners and refugees in German society. According to the council, German integration policy should not only focus on immigrants, but also provide courses on integration for groups such as Pegida. Praising German Chancellor Angela Merkel's distancing herself from Pegida, the Council stressed that an immigration society is a very complex construct.[158]

Political theorist Wolfgang Jäger considers Pegida a part of increasingly right-wing populist tendencies in Europe, in their Islamophobia possibly being the heir to widespread antisemitism. He claims that the demonstrations themselves expose the movement's moderate position paper as a fig leaf for "blatantly unconstitutional xenophobia". Thus, democrats should not sympathize with the movement, as their referring in particular to Judeo-Christian values was contrary to their actual demands. Jäger also voiced concerns about the "ghosts of the old nationalism re-entering Germany through the back door". According to political theorists, a democracy needs to be measured by how it protects its minorities. A knowledge of foreign cultures should be taught in schools. Only in this way would it be possible to understand globalisation as a chance for cultural enrichment in the face of global terrorism.[159]

International reactions

[edit]The controversy around Pegida sparked reactions from international media as well. In France, Le Monde wrote that Islamophobia divided German society, while Libération and L'Opinion discussed possible parallels to the French far-right National Front.[160] Several French and francophone cartoonists published a flyer aimed against a funeral march by Pegida in the wake of the Charlie Hebdo shooting in January 2015. The signatories – among them a surviving member of Charlie Hebdo's editorial staff – disapproved of Pegida using the mourning to gather attention for their own cause. They stated that Pegida symbolised everything Charlie Hebdo had fought against and asked the population of Dresden for more tolerance and to be open towards different cultures.[161]

The Times claimed that, for the first time since 1945, a German populist movement was publicly complaining about an ethnic minority. This would frighten the establishment. BBC News said that Germany is not used to such large numbers of demonstrators supporting such positions.[162] The Guardian described Pegida as an emerging campaign against immigrants that would eventually endanger tourism.[163]

The New York Times claimed that, because of its communist history, East Germany was more xenophobic than the rest of the country. The paper claimed that, in light of the low numbers of Muslims living in Saxony, the fear of Islamisation was bizarre.[164]

Russia Today reported comprehensively on Pegida. Its subsidiary Ruptly broadcast several rallies live on the internet.[165]

Turkey's Hürriyet and Sabah reported on Pegida and counterrallies. Sabah interpreted the demonstrations as a "rise of the radical right in Europe". In an interview with the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, Turkish prime minister Ahmet Davutoğlu compared Pegida followers with members of the terror organisation IS. He said that both had an archaic mindset and that Turkey was "very concerned about Pegida". He called the movement a "threat to Turks, Muslims and Germany itself".[166]

The Arabic news network Al Jazeera primarily reported on counter-demonstrations.[162]

Offshoots and variations

[edit]In Germany

[edit]Pegida has spawned a number of smaller offshoots across Germany, including Legida in Leipzig, Sügida in southern Thuringia,[72] Kagida in Kassel, Wügida in Würzburg, Bogida in Bonn, Dügida in Düsseldorf,[69] and Fragida in Frankfurt.[167] After some internal disputes, representatives of Pegida NRW, an affiliate aiming to operate in the federal state of North Rhine Westphalia, distanced itself from the Bogida, Dügida and Kögida clones in North Rhine–Westphalia. The latter were said to have been taken over by members of the openly xenophobic right-wing splinter party Pro NRW.[168] In January 2015, Pegida NRW replaced their media representative Melanie Dittmer with Sebastian Nobile, a member of the German Defence League, an anti-Islamist organisation modelled on the English Defence League.[169]

In December 2014, rival right-wing forces founded an anti-American Facebook group under the name PEGADA (German: Patriotische Europäer gegen die Amerikanisierung des Abendlandes, or "Patriotic Europeans Against the Americanisation of the West"), claiming the true problem was not the phenomenon of Islamism but the suspected American forces behind it. On 25 January they held a first rally in Erfurt under the title EnDgAmE (Engagierte Demokraten gegen die Amerikanisierung Europas, or "Committed democrats against the Americanisation of Europe"). Promoted by a number of activists of the Third Position Mahnwachen-Movement and by Hooligans against Salafists (Hogesa).[170] They attracted some 1,000 protesters, but were opposed by 800 mostly left-wing counter-demonstrators[171] including Erfurt's mayor Andreas Bausewein and trade union members, Jusos and the local Antifa.[72]

Another offshoot, Nügida, drew scrutiny after several of its members became involved in a neo-Nazi plot to bomb a refugee centre.[172]

International

[edit]

In January 2015, Pegida sympathizers held their first rally in Oslo, Norway, with around 200 protesters led by Max Hermansen,[173] but this support quickly collapsed.[174][175] In neighbouring Denmark, around 200 protesters marched in the capital, Copenhagen.[176] In the same month, a Spanish branch applied for a protest outside the main mosque in Madrid, which was rejected by government officials.[177] Marches were planned in Switzerland and Antwerp, Belgium, but not permitted due to anti-terrorism raids in Verviers one week earlier.[178] The Antwerp demonstration was finally held on 2 March 2015 without the mayor's permission. About 350 persons were present and about 227 of them were fined for participating in an unauthorised demonstration.

On 28 February 2015, Pegida UK held its first protest in Newcastle upon Tyne, with around 400 attending. Around 1,000 people turned up to oppose, led by former MP George Galloway.[179] There was a small Pegida demonstration in London on 4 April 2015, with a counter-demonstration by anti-fascist groups.[180]

The first Pegida demonstration in Sweden gathered eight people in Malmö and 5,000 opponents.[181][182] When Pegida called a demonstration in Linköping they gathered four persons.[183] In Uppsala, Pegida managed to gather about ten persons.[184] Following several failed demonstrations and internal strife the Swedish branch dissolved.[185]

A demonstration on 28 March 2015 in Montreal, Canada, by sympathizers of Pegida was cancelled when hundreds of people gathered to counter-protest.[186] A demonstration on 19 September 2015 in Toronto was attended by about a dozen members of Pegida Canada. The demonstration ended in a melee with counter-protesters who outnumbered Pegida members about twenty to one.[187][self-published source]

Political scientist Farid Hafez argues that Pegida was not able to settle down in Austria, since the far right FPÖ already represented the ideology of Pegida in parliament and absorbed most of the far right human resources.[188]

Pegida Ireland had planned to have its inaugural rally in Dublin on 6 February 2016, during which Identity Ireland's Peter O’Loughlin, who was also to be chairman of Pegida Ireland, was to speak. While on his way to the rally on a tram, he and members of the movement were attacked by a group of men wearing black masks.[189][190] The planned rally never took place. A group of Pegida supporters was attacked and chased into a store by a group who broke away from a counter-demonstration.[191][192]

Fortress Europe

[edit]On 23 January 2016, representatives of 14 like-minded allies, including Pegida Austria, Pegida Bulgaria, and Pegida Netherlands, met with Lutz Bachmann and Tatjana Festerling in the Czech Republic to sign the Prague Declaration, which states their belief that the "history of Western civilisation could soon come to an end through Islam conquering Europe", thus formalizing their membership in the Fortress Europe coalition against that eventuality. Other signatories present were the Czech organizations Bloc Against Islam, Odvaha and Dawn – National Coalition, with the Polish National Movement, the Conservative People's Party of Estonia, and Italy's Lega Nord. Dawn's Marek Černoch said that the meeting was, among other things, a reaction to the attacks on women in Cologne in Germany on New Year's Eve, which took place as celebrations were being held to usher in 2016. At the end of the Prague Declaration, above the signatures, it is stated that there would be demonstrations on 6 February 2016 to manifest their determination. Others who joined Fortress Europe or participated in Pegida-organised demonstrations are: Identity Ireland, Pegida Switzerland, Pegida UK, Riposte Laïque, Republican Resistance, For Frihed, Reclaim Australia, and former French Foreign Legion General Christian Piquemal's group in Calais.[193][194][195][196]

Literature

[edit]- Patzelt, Werner J.; Klose, Joachim (2016). PEGIDA. Warnsignale aus Dresden (in German). Thelem.

See also

[edit]- Birlikte

- Counter-jihad

- Eurabia

- Islamic fundamentalism

- Jihad and Jihadism

- Stop Islamisation of Europe

- Demographics of Europe

- Identitarian movement

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ The use of the flag gained particular attention in Norway after confusion due to the flag's close resemblance, especially under certain light conditions, with Norway's national flag.[66][67][68]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Virchow, Fabian (2016), "PEGIDA: Understanding the Emergence and Essence of Nativist Protest in Dresden", Journal of Intercultural Studies, 37 (6): 541–555, doi:10.1080/07256868.2016.1235026, S2CID 151752919

- ^ "PEGIDA in Germany".

- ^ a b "The Pegida Movement and German Political Culture: Is Right-Wing Populism Here to Stay?"

- ^ Popp, Maximilian; Wassermann, Andreas (12 January 2015). "Prying into Pegida: Where Did Germany's Islamophobes Come From". Der Spiegel. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- ^ Amtsgericht Dresden, Aktenzeichen: VR 7750.

- ^ "PEGIDA in Germany".

- ^ a b c d e Connolly, Kate (6 January 2015). "Pegida: what does the German far-right movement actually stand for?". The Guardian. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- ^

- Alexander I. Stingl (16 December 2015). The Digital Coloniality of Power: Epistemic Disobedience in the Social Sciences and the Legitimacy of the Digital Age. Lexington Books. ISBN 978-1-4985-0193-4.

has led, induced by the media event that is ISIS, to the resurgence of a populist demonstration culture in PEGIDA (Patriotic Europeans Against the Islamisation of the Occident) on the extreme Right, which has found supporters in the ...

- "PEGIDA in Germany".

- "The Pegida Movement and German Political Culture: Is Right-Wing Populism Here to Stay?"

- Bayraklı, Enes; Farid Hafez (23 March 2016). European Islamophobia Report 2015. SETA. p. 56. ISBN 978-605-4023-68-4.

Although founded in neighbouring Germany, PEGIDA has gained some support in Belgium. Support for the far-right and Islamophobic organisation is more keenly seen in Dutch-speaking Flanders, than in francophone Wallonia and Brussels.

- Margetts, Helen; John, Peter; Hale, Scott A.; Yasseri, Taha (2016). Political turbulence: how social media shape collective action. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. p. 3. ISBN 9780691159225.

Some have seen the rise of far-right and anti-Islamist groups, as in Germany where protests by the Patriotic Europeans Against the Islamisation of the Occident (PEGIDA) have been attended by thousands, matched by a counter-movement of ...

- Greg Albo; Leo Panitch (22 December 2015). The Politics of the Right: Socialist Register 2016. Monthly Review Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-58367-575-5.

Pegida is a classic far-right anti-immigration movement.

- Shannon Latkin Anderson (19 November 2015). Immigration, Assimilation, and the Cultural Construction of American National Identity. Taylor & Francis. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-317-32875-9.

In Germany, the far-right anti-Islam movement Pegida found massive audience in its anti-Islamic, anti-immigration marches

- "Anti-Islam Organization PEGIDA Is Exporting Hate Across Europe". Newsweek.

The 200 or so demonstrators trudging down the road are supporters of PEGIDA, a far-right German group whose name is an acronym for Patriotic Europeans Against the Islamization of the Occident.

- "France bans march through Calais by far-right Pegida group". International Business Times.

- "Germany's refugee crisis is fueling the far-right Pegida movement". Public Radio International.

- "Germany reveals plans to relax deportation rules for foreign criminals". CNN.

Protesters from the far-right PEGIDA movement attend a rally in Leipzig on Monday

- Alexander I. Stingl (16 December 2015). The Digital Coloniality of Power: Epistemic Disobedience in the Social Sciences and the Legitimacy of the Digital Age. Lexington Books. ISBN 978-1-4985-0193-4.

- ^ a b c d "The End of Tolerance? Anti-Muslim Movement Rattles Germany". Der Spiegel. 21 December 2014. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ^ "Who goes to German Pegida 'anti-Islamisation' rallies". BBC News. 13 January 2015.

- ^ "Germany anti-Islamic protests: Biggest Pegida march ever in Dresden as rest of Germany shows disgust with lights-out". The Independent. 5 January 2015. Archived from the original on 5 January 2015.

- ^ "Germany's Pegida anti-Islam movement unravelling". The Daily Telegraph. 28 January 2015.

- ^ a b c Knight, Ben (23 February 2015). "Pegida head Lutz Bachmann reinstated after furore over Hitler moustache photo". The Guardian. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

- ^ Perwee, Ed (2020). "Donald Trump, the anti-Muslim far right and the new conservative revolution". Ethnic and Racial Studies. 43 (16): 211–230. doi:10.1080/01419870.2020.1749688. S2CID 218843237.

- ^ Bremer, Nils (5 January 2015). "Auch die Gegner organisieren sich". Journal Frankfurt. Retrieved 21 June 2016.

- ^ Iskandar, Katharina (27 January 2015). "Auch die Gegner organisieren sich". Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. Retrieved 21 June 2016.

- ^ Weiß, Volker (12 December 2014). "Islam-Gegner und rechte Szene: Pegida ist die neue Abkürzung für 'Ausländer raus'". Der Spiegel. Retrieved 21 June 2016.

- ^ Connolly, Kate (15 December 2014). "Estimated 15,000 people join 'pinstriped Nazis' on march in Dresden". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ "PEGIDA-Erfinder: Wir hören erst auf, wenn die Asyl-Politik sich ändert! – Dresden". Bild (in German). 1 December 2014. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- ^ Bachmann, Lutz. "Kurden Demo Dresden" (in German). Retrieved 5 January 2015 – via YouTube.

- ^ Popp, Maximilian; Wassermann, Andreas (12 January 2015). "Prying into Pegida: Where Did Germany's Islamophobes Come From?". Der Spiegel. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- ^ "Kurds and Islamists brawl in Hamburg". The Local. 8 October 2014. Retrieved 17 March 2019.

- ^ Locke, Stefan (25 January 2016). "Pegida: Bewegung gegen Islamisierung des Abendlandes". Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- ^ a b c d Smale, Alison (7 December 2014). "In German City Rich With History and Tragedy, Tide Rises Against Immigration". The New York Times. Retrieved 16 December 2014.

- ^ Kirschbaum, Erik (16 December 2014). "Patriotic Europeans Against the Islamisation of the West quickly gathering support in Germany". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 16 December 2014.

- ^ Stute, Dennis (7 December 2014). "Anti-Islamist protests with right-wing ties expand in Germany". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 9 December 2014.

- ^ "Dresdner Tafel will kein Geld von PEGIDA". Morgenpost Sachsen. 22 December 2014. Archived from the original on 19 January 2015. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- ^ Fischer, Christian (12 January 2015). "So will Pegida mit den Demos Geld machen". Bild (in German). Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- ^ "35.000 Dresdner demonstrieren für Toleranz" (in German). Mitteldeutscher Rundfunk. 13 January 2015. Archived from the original on 11 January 2015. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- ^ Brady, Kate (12 January 2015). "Record turnout at Dresden PEGIDA rally sees more than 25,000 march". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- ^ Connolly, Kate (15 January 2015). "Killing of Eritrean refugee in Dresden exposes racial tensions in Germany". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- ^ "Arrest made over the death of Dresden asylum seeker". Deutsche Welle. 22 January 2015. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- ^ "Fünf Jahre Haft wegen Totschlags". Mitteldeutsche Rundfunk Sachsen. 6 November 2015. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- ^ Sommers, Jack (18 January 2015). "Pegida Cancel Lastest [sic] Dresden Demonstration After Threats". Huffington Post UK. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- ^ "Dresdner Polizei verbietet Demos wegen Anschlagsgefahr". Reuters. 18 January 2015. Archived from the original on 19 January 2015. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- ^ a b Wagstyl, Stefan (21 January 2015). "German populist leader quits after Hitler pose emerges". Financial Times. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- ^ "PEGIDA founder Bachmann quits after Hitler mustache photo". Deutsche Welle. 21 January 2015.

- ^ a b Connolly, Kate (21 January 2015). "Photograph of Germany's Pegida leader styled as Adolf Hitler goes viral". The Guardian. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- ^ a b Chambers, Madeline (21 January 2015). "German PEGIDA leader investigated after Hitler pose". Reuters. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- ^ "Skandal um Lutz Bachmann: AfD beriet Pegida in Hitler-Affäre". Der Spiegel. 23 January 2015. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- ^ Brown, Stephen; Hudson, Alexandra (28 January 2015). "German anti-Islam group PEGIDA loses second leader in a week". Reuters. Archived from the original on 18 December 2015. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- ^ "Germany Pegida: Leader Kathrin Oertel quits protest group". BBC News. 28 January 2015. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- ^ Connolly, Kate (3 February 2015). "Former Pegida head starts 'less radical' splinter group". The Guardian. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- ^ "Bachmann stellt Vertrauensfrage". Sächsische Zeitung. 20 June 2016. Retrieved 27 June 2016.

- ^ "Merkel's CDU suffers setback in Dresden mayoral poll". Deutsche Welle. 8 June 2013. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- ^ "Pegida will bei Landtagswahlen antreten". Süddeutsche Zeitung. 7 July 2015. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- ^ Smale, Alison (21 October 2015). "Anti-Immigrant Violence in Germany Spurs New Debate on Hate Speech". The New York Times. Retrieved 22 October 2015.

- ^ Huggler, Justin (20 October 2015). "Warnings over resurgence of German far-Right movement Pegida sparked by refugee crisis". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 22 October 2015.

- ^ Janosch Delcker (6 October 2015). "German anti-immigrant protests revive – and radicalize". Politico Europe. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- ^ "Two Journalists Injured While Reporting on Pegida Movement in Germany". The Typewriter. 1 October 2015.

- ^ "Germany: prosecutors probe mock gallows at PEGIDA rally". The Washington Post. 13 October 2015. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- ^ "Lächerliche Bastelarbeit mit Schreibfehlern". Stern. 13 October 2015. Retrieved 25 January 2016.

- ^ "Warnings over resurgence of German far-Right movement Pegida sparked by refugee crisis". The Daily Telegraph. 20 October 2015. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- ^ "Eklat bei Pegida-Demo: 'Die KZs sind ja leider derzeit außer Betrieb'". Der Spiegel. 20 October 2015. Retrieved 5 March 2016.

- ^ Niggemeier, Stefan (1 November 2015). "Die Unwahrheit über Akif Pirinçcis 'KZ-Rede'". Journalist. Retrieved 5 March 2016.

- ^ "Germany's PEGIDA condemned over 'concentration camp' speech". The Times of Israel. 20 October 2015. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- ^ "Outrage over concentration camp quip at PEGIDA speech". Deutsche Welle. 20 October 2015. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- ^ "Leipzig police arrest hundreds after far-right hooligans' violent rampage". Deutsche Welle. 12 January 2016.

- ^ "Dresden: Pegida-Anhänger gründen offenbar eigene Partei". Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (in German). 19 July 2016. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

- ^ Allchorn, William (2016), Cut from the same cloth? Pegida UK looks like a sanitised version of the EDL, British Politics and Policy at LSE

- ^ "Pegida Positionspapier" (PDF) (in German). menschen-in-dresden.de. 10 December 2014.

- ^ a b "The uprising of the decent". The Economist. 10 January 2015. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- ^ "Lying Press? Germans Lose Faith in the Fourth Estate". Spiegel Online. 24 February 2016. Retrieved 5 August 2016.

- ^ "Hundreds attend anti-immigration rally in wake of Cologne sex attacks". Yahoo! News. 9 January 2015.

- ^ "Symbolik bei Demos: Warum bei Pegida die Kreuz-Fahne weht". Der Spiegel. 29 July 2015.

- ^ "Norsk-lignende flagg i Pegida-demonstrasjoner". Dagen. 26 January 2015.

- ^ "Nei, det er ikke det norske flagget". NRK. 21 October 2015.

- ^ "10 000 demonstrerte mot islam i Tyskland. Dette er flagget de veiver med". Dagbladet. 12 October 2015.

- ^ a b Knight, Ben (15 December 2014). "PEGIDA determining political debate in Germany". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- ^ Honnigfort, Bernhard (15 December 2014). "Pegida veröffentlicht Positionspapier". Frankfurter Rundschau (in German). Retrieved 16 December 2014.

- ^ Eddy, Melissa (21 January 2015). "German Anti-Immigrant Figure Quits Post After Posing as Hitler". The New York Times.

- ^ a b c "Knapp 2.000 Teilnehmer bei Kundgebungen". Mitteldeutscher Rundfunk (in German). 24 January 2015. Archived from the original on 27 January 2015. Retrieved 24 January 2015.

- ^ "The Theses of Dresden" (PDF) (in German). Pegida. February 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016 – via i-finger.de.

- ^ "Lutz Bachmann und Pegida: Der Thesenanschlag von Dresden". Tagesspiegel. Retrieved 18 February 2016.

- ^ "'Dresdner Thesen': PEGIDA radikalisiert sich nun auch schriftlich". Netz Gegen Nazis (in German). Archived from the original on 6 February 2017. Retrieved 18 February 2016.

- ^ "Demo in Dresden bleibt friedlich – Teilnehmerzahl weit unter Erwartungen". DNN-Online (in German). 27 October 2014. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- ^ "Polizeieinsatz" (in German). Polizei Sachsen. 3 November 2014. Archived from the original on 23 December 2014. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- ^ "Polizei Sachsen" (in German). Polizei Sachsen. 10 November 2014. Archived from the original on 16 December 2014. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- ^ "Polizeieinsatz" (in German). Polizei Sachsen. 17 November 2014. Archived from the original on 23 December 2014. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- ^ Locke, Stefan (23 December 2014). "Demonstration in Dresden: Spezialeinheit Abendland". FAZ Net (in German). FAZ. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- ^ "Polizeieinsatz" (in German). Polizei Sachsen. 1 December 2014. Archived from the original on 15 December 2014. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- ^ "Polizeieinsatz" (in German). Polizei Sachsen. 8 December 2014. Archived from the original on 15 December 2014. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- ^ "Polizeieinsatz" (in German). Polizei Sachsen. 15 December 2014. Archived from the original on 16 December 2014. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- ^ "Polizeieinsatz" (in German). Polizei Sachsen. 22 December 2014. Archived from the original on 23 December 2014. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- ^ Tiede, Peter (22 December 2014). "Evangelische Kirche Deutschlands Pegida ist unchristlich". Bild (in German). Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- ^ "Polizeieinsatz" (in German). Polizei Sachsen. 5 January 2015. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- ^ Polizeieinsatz. In: Polizei Sachsen. Januar 12, 2015

- ^ "Germany: Anti-Islam Pegida protest rally draws record 25,000 in Dresden". International Business Times. 12 January 2015. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- ^ "Polizeieinsatz". Polizei Sachsen. 25 January 2015. Archived from the original on 5 February 2015. Retrieved 26 January 2015.

- ^ "Polizeieinsatz". Polizei Sachsen. 9 February 2015. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- ^ "Polizeieinsatz". Polizei Sachsen. 16 February 2015. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- ^ "Polizeieinsatz". Polizei Sachsen. 23 February 2015. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- ^ "Polizeieinsatz". Polizei Sachsen. 2 March 2015. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- ^ "Polizeieinsatz". Polizei Sachsen. 9 March 2015. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- ^ "Polizeieinsatz". Polizei Sachsen (in German). 16 March 2015. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- ^ "Polizeieinsatz" (in German). Polizei Sachsen. 22 December 2014. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- ^ "Polizeieinsatz" (in German). Polizei Sachsen. 5 January 2015. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- ^ "Polizeieinsatz" (in German). Polizei Sachsen. 6 April 2015. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- ^ "Wilders beschert Pegida nicht erhofften Zulauf". MDR Sachsen. 13 April 2015. Archived from the original on 22 October 2015. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- ^ "Polizeieinsatz" (in German). Polizei Sachsen. 5 May 2015. Retrieved 12 January 2016.

- ^ "Polizeieinsatz" (in German). Polizei Sachsen. 25 May 2015. Retrieved 12 January 2016.

- ^ "Polizeieinsatz" (in German). Polizei Sachsen. 1 June 2015. Retrieved 12 January 2016.

- ^ "Neues aus der Tabuzone". Die Zeit (in German). 17 December 2014. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- ^ Jansen, Frank (19 January 2015). "Sachsen im Fokus der Dschihadisten". Der Tagesspiegel (in German). Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- ^ Huber, Joachim (18 December 2014). "Pegida und die 'Lügenpresse'. 'Wort im Mund umdrehen'". Der Tagesspiegel. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- ^ Federl, Fabian; Meisner, Matthias (21 January 2015). "Hitler-Verkleidung, Flüchtlinge als 'Viehzeug'. Die Hintergründe zum Fall Lutz Bachmann". Der Tagesspiegel. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- ^ "Pegida: Das sind die Köpfe der Bewegung". Merkur Online. 12 February 2015.

- ^ Hauser, Uli (15 December 2014). "Die Köpfe hinter Pegida. Wutbürger, die nicht reden wollen". Der Stern.

- ^ Locke, Stefan (16 December 2014). "Pegida-Organisatoren. Die im Dunkeln sieht man nicht". Frankfurter Allgemeine.

- ^ Dobmeier, Steffi; Jacobson, Lenz (9 December 2014). "Dresden. Die wichtigsten Thesen von Pegida". Die Zeit.

- ^ Meier, Albrecht; Niewendick, Martin (9 December 2014). "Kundgebung der Islam-Hasser in Dresden Innenminister de Maizière: 'Pegida ist eine Unverschämtheit'". Der Tagesspiegel.

- ^ Dieckmann, Christoph; Fuchs, Christian (17 December 2014). "Schwerpunkt: Pegida – vereint in Wut und Angst. Neues aus der Tabuzone". Die Zeit.

- ^ Pollmer, Cornelius; Schneider, Jens; Bielicki, Jan (3 December 2014). "Demos gegen Islamisten. Rechts orientierte Wutbürger". Süddeutsche Zeitung.

- ^ "Vereinsregister des Amtsgerichts Dresden". Blatt VR 7750.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Pegida will Steuerbegünstigung". Die Zeit. 10 January 2015.

- ^ "Dresden setzt Zeichen für Weltoffenheit – 35.000 Menschen bei Kundgebung gegen Pegida". DNN online. 11 January 2015. Archived from the original on 13 January 2015. Retrieved 12 January 2015.

- ^ "Germany protests: Dresden marches against anti-Islamists Pegida". BBC News. 10 January 2015. Archived from the original on 11 January 2015. Retrieved 12 January 2015.

- ^ "Deutschlandweit Proteste gegen Islamfeinde". Frankfurter Allgemeine. 12 January 2015. Retrieved 12 January 2015.

- ^ "Cologne Cathedral to turn out the lights in protest at anti-Muslim march". Reuters. 2 January 2015. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ^ a b "Germany Pegida protests: 'Islamisation' rallies denounced". BBC News Online. 6 January 2015. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- ^ "Anti-Islam-Bewegung 'Pegida': Mehrheit der Ostdeutschen zeigt Verständnis". N24. 14 December 2014. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ^ "Deutsche vermuten Neonazis und besorgte Bürger hinter PEGIDA". Presseportal. 11 December 2014. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ^ "Anti-Islam-Proteste: Jeder Zweite sympathisiert mit Pegida". Die Zeit. 15 December 2014. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ^ "Spiegel-Umfrage zur Flüchtlingspolitik: Deutsche fühlen sich von Regierung übergangen". Der Spiegel. 13 December 2014. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ^ "Protest gegen angebliche Islamisierung – So viele Deutsche würden bei Pegida mitmarschieren". Focus. 20 December 2014. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ^ Mathes, Werner (1 January 2015). "Stern-Umfrage: 13 Prozent der Deutschen würden für Pegida marschieren". Stern. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ^ Löbbert, Raoul (8 January 2015). "Religionsmonitor: 57 Prozent der Deutschen fühlen sich vom Islam bedroht". Zeit Online. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ^ "Angela Merkel issues New Year's warning over rightwing Pegida group". The Guardian. 30 December 2014. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- ^ "Protest-Märsche: De Maizière zeigt Verständnis für Pegida-Demonstranten". Der Spiegel. 12 December 2014. Retrieved 16 December 2014.

- ^ Hill, Jenny (16 December 2014). "Anti-Islam 'Pegida' march in German city of Dresden". BBC News Online. Retrieved 16 December 2014.

- ^ Hugglet, Justin (10 December 2014). "German Eurosceptics embrace anti-Islam protests". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 16 December 2014.

- ^ "Erklärung der AfD-Fraktion im Stadtrat der Landeshauptstadt Dresden zu den Demonstrationen von PEGIDA" (in German). Alternative for Germany. 20 November 2014. Archived from the original on 5 January 2015. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- ^ "German Council of Jews chairman condemns 'immensely dangerous' PEGIDA movement". Deutsche Welle. 20 December 2014. Retrieved 22 December 2014.

- ^ "Bischof will ehrlichen Dialog mit Muslimen über IS" [Bishop wants honest dialogue with Muslims on IS]. Die Welt (in German). 24 December 2014. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- ^ "German xenophobia: Peaceful, but menacing". The Economist. 20 December 2014.

- ^ "Pläne in Sachsen: Sondereinheit soll gegen straffällige Asylbewerber 'durchgreifen'" [Plans in Saxony: Special unit to clamp down on criminal asylum seekers]. Der Spiegel (in German). 24 November 2014. Retrieved 9 January 2015.

- ^ Kuhne, Robert (24 November 2014). "Innenminister Ulbig zur Asylpolitik". MOPO24 (in German) – via YouTube.

- ^ "Bärgida und Gegendemonstration beendet". Tagesspiegel (in German). 5 January 2015. Retrieved 20 November 2015.

- ^ "Licht aus am Brandenburger Tor" [Lights off at Brandenburg Gate] (in German). Rundfunk Berlin-Brandenburg. 5 January 2015. Archived from the original on 13 May 2015. Retrieved 20 November 2015.

- ^ "Anti-islamisation rally in Germany met with countrywide protests". 5 January 2015. Archived from the original on 20 November 2015. Retrieved 20 November 2015 – via Storify.

- ^ "Licht aus gegen Pegida" [Lights off against Pegida]. Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (in German). 5 January 2015. Retrieved 20 November 2015.

- ^ "Security Message for U.S. Citizens: Berlin (Germany), Demonstration Notice". Overseas Security Advisory Council, Bureau of Diplomatic Security, U.S. Department of State. 26 January 2015. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- ^ "Philosophische Fakultät – Lehrstuhlinhaber" (in German). TU Dresden. 19 January 2015. Archived from the original on 8 January 2015. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- ^ Hach, Oliver (28 November 2014). "Pegida – oder: Die Welle". FreiePresse. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ^ "Des 'patriotes' allemands se mobilizent contre l'immigration" [German "patriots" mobilising against immigration]. Le Temps (in French). 11 December 2014. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ^ a b Pabst, Sabrina (17 February 2015). "Jaschke: Jetzt ist die Zivilgesellschaft gefragt". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ^ Lachmann, Harald (8 December 2014). "Dresden und der Pegida-Protest: Sorge um die weltoffene Stadt". Stuttgarter Zeitung. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ^ Bohmann, Christin (1 December 2014). "Extremismus-Forscher: 'Pegida spricht aus, was die Leute denken'". Mitteldeutscher Rundfunk. Archived from the original on 19 February 2015. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ^ Gensing, Patrick (1 December 2014). "Pegida- und HoGeSa-Demonstrationen: Gegen Islamismus, für 'Heimatschutz'". Tagesschau. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ^ Kandzora, Jan (8 December 2014). "Proteste gegen Asyl und Islam: Das steckt hinter Pegida und Bagida". Augsburger Allgemeine. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ^ Lühmann, Michael (16 December 2014). "Dresden: Pegida passt nach Sachsen". Die Zeit. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ^ Aly, Götz (15 December 2014). "Pegida, eine alte Dresdner Eigenheit". Berliner Zeitung. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ^ Manemann, Jürgen (22 December 2014). "InDebate: Pegida ist eine anti-politische Bewegung!". Philosophie Indebate. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ^ Schwan, Gesine (30 December 2014). "Fremdenhass: Pegida ist überall". Zeit Online. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ^ Cordsen, Knut (17 December 2014). "Patriotismus oder Vorurteile? Historiker Wolfgang Benz über die Pegida-Proteste". Bayerischer Rundfunk. Archived from the original on 20 January 2015. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ^ Cordsen, Knut (5 January 2015). "Die Pegida-Demonstrationen als neues Phänomen für Fremdenfeindlichkeit". Endstation Rechts. Archived from the original on 9 January 2015. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ^ Kurz, Peter (2 January 2014). "Politologe Pfahl-Traughber zu Pegida: 'Bevormundung der Basis'". Westdeutsche Zeitung. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ^ Reimann, Anna (5 January 2014). "Umgang mit Pegida: Forscher fordern neues Deutschland-Bild in Lehrplänen". Der Spiegel. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ^ Jäger, Wolfgang (10 January 2014). "Die Gespenster des völkischen Nationalismus". Badische Zeitung. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ^ Wiegel, Michaela. "Ist Pegida ein deutscher Front National?". Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- ^ "Französische Karikaturisten wehren sich gegen Pegida". Die Zeit. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- ^ a b "Das moderne Deutschland ist das nicht gewohnt". Die Zeit. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- ^ Salloum, Raniah (16 December 2014). "Ausländische Medien über Pegida: 'Im Tal der Ahnungslosen'". Der Spiegel. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- ^ Smale, Alison (8 December 2014). "In German City Rich With History and Tragedy, Tide Rises Against Immigration". The New York Times. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- ^ Reimann, Anna (6 January 2015). "Weltpresse über deutsche Islamfeinde: 'Die Rhetorik von Pegida ist armselig'". Der Spiegel. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- ^ "Türkischer Regierungschef vergleicht Pegida mit IS". Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- ^ Gedziorowski, Lukas (15 December 2014). "Pegida wird Fragida". Journal Frankfurt (in German). Retrieved 16 December 2014.

- ^ Burger, Reiner (12 January 2015). "Schwarze Pädagogik, die wir nicht nötig haben". Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (in German). Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- ^ "Pegida-NRW feuert Pressesprecherin und will Köln künftig meiden". Kölner Stadt-Anzeiger (in German). 6 January 2015. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- ^ Freires, Horst (22 January 2015). "Pegada statt Pegida". Blick nach Rechts (in German). Retrieved 24 January 2015.

- ^ "Scuffles as anti-American protesters meet resistance in Germany". Europe Online. 24 January 2015. Retrieved 24 January 2015.

- ^ "Police foil right-wing extremist plot to bomb German migrant shelters with 'highly dangerous explosives'". National Post. 23 October 2015.

- ^ Chambers, Madeline (14 January 2015). "PEGIDA's anti-Muslim calls shake up German politics". Reuters. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- ^ "Pegida sees 'complete failure' in Norway". The Local. 10 February 2015. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- ^ "Pegida i Norge i full oppløsning" (in Norwegian). NRK Trøndelag. 24 March 2015. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- ^ Brabant, Malcolm (23 January 2015). "PEGIDA Denmark takes cue from Germany". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 24 January 2015.

- ^ "Anti-Islamist movement Pegida surfaces in Spain". The Daily Telegraph. 14 January 2015. Retrieved 24 January 2015.

- ^ "Antwerp cancels PEGIDA Flanders demonstration over security fears". Reuters. 22 January 2015. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- ^ "'Anti-Islamisation' group Pegida UK holds Newcastle march". BBC News. 28 February 2015. Retrieved 2 March 2015.

- ^ Dearden, Lizzie. "Pegida in London: British supporters of anti-'Islamisation' group rally in Downing Street". The Independent. Archived from the original on 25 May 2022. Retrieved 4 April 2015.

- ^ "Åtta från Pegida – 5 000 motdemonstranter". Sydsvenskan (in Swedish). 9 February 2015. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- ^ Andreas Örwall Lovén (9 February 2015). "Få deltog i första Pegida-aktionen". Svenska Dagbladet (in Swedish). Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- ^ "Endast fyra demonstrerade med Pegida i Linköping". Expo (in Swedish).

- ^ "Kravallstaket runt Forumtorget". Upsala Nya Tidning. 16 May 2015.

- ^ "Svenska Pegida lägger ner".

- ^ Lindeman, Tracey (28 March 2015). "PEGIDA Québec cancels march after anti-racist groups convene. Anti-Islam group with European roots and National Front sympathies organizes in Quebec". CBC News.

- ^ Rias, Liberta (23 September 2015). "Antifascists Crush 'PEGIDA Canada'" – via Vimeo.

- ^ Hafez, Farid (1 December 2016). "Pegida in Parliament? Explaining the Failure of Pegida in Austria". German Politics and Society. 34 (4): 101–118. doi:10.3167/gps.2016.340407.

- ^ Roche, Barry (9 February 2016). "Varadkar concerned by rise of anti-Islamic group Pegida". The Irish Times. Retrieved 14 March 2016.

- ^ Roche, Barry (30 January 2016). "Anti-Islamic group Pegida Ireland to be launched at Dublin rally". The Irish Times. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- ^ Clancy, Paddy (11 February 2016). "Anti-Islam group chased by anti-racism protesters in Dublin (VIDEO)". IrishCentral. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- ^ Griffin, Dan (7 February 2016). "RTÉ to file complaint after cameraman is injured in protest". The Irish Times. Retrieved 12 March 2016.

- ^ Nissen, Anita (2022). Europeanisation of the Contemporary Far Right: Generation Identity and Fortress Europe. Routledge. p. 18. ISBN 9781000547085.

- ^ "Pegida meets with European allies in the Czech Republic". Deutsche Welle. 23 January 2016. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- ^ Roche, Barry (30 January 2016). "Anti-Islamic group Pegida Ireland to be launched at Dublin rally". The Irish Times. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- ^ Lüssi, Marco (7 March 2016). "Pegida Schweiz wirft Ignaz Bearth raus". 20 Minuten (in German). Retrieved 13 March 2016.

Further reading

[edit]- Rosellini, Jay. The German New Right: AfD, PEGIDA and the Re-Imagining of National Identity (Hurst, 2020) online review

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to PEGIDA at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to PEGIDA at Wikimedia Commons