Penobscot

Pαnawάhpskewi | |

|---|---|

Seal of the Penobscot Indian Nation | |

| Total population | |

| 2,278 enrolled members[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 2,278 (0.2%) | |

| Languages | |

| Abenaki, English | |

| Religion | |

| Wabanaki mythology, Christianity | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Abenaki, Wolastoqiyik, Mi'kmaq, Passamaquoddy | |

The Penobscot (Abenaki: Pαnawάhpskewi) are an Indigenous people in North America from the Northeastern Woodlands region. They are organized as a federally recognized tribe in Maine and as a First Nations band government in the Atlantic provinces and Quebec.[citation needed]

The Penobscot Nation, formerly known as the Penobscot Tribe of Maine, is the federally recognized tribe of Penobscot in the United States.[2] They are part of the Wabanaki Confederacy, along with the Abenaki, Passamaquoddy, Wolastoqiyik, and Miꞌkmaq nations, all of whom historically spoke Algonquian languages. The Penobscots' main settlement is now the Penobscot Indian Island Reservation, located within the state of Maine along the Penobscot River.

Name

[edit]The Penobscot's name for themselves, Pαnawάhpskewi, means "the people of where the white rocks extend out". It originally referred to their territory on the portion of the Penobscot River between present-day Old Town and Verona Island, Maine. It was misheard by European colonizers as "Penobscot", which gives them their name today.

Government

[edit]The Penobscot Nation is headquartered in Penobscot Indian Island Reservation, Maine. The tribal chief is Kirk Francis.[2] The vice-chief is Bill Thompson. The Penobscot are invited to send a nonvoting representative to the Maine House of Representatives.

In 2005, Penobscot Nation began a relationship with Venezuela's government led by Hugo Chavez. It accepted aid in the form of heating oil. Tribal chief Kirk Francis traveled to New York City to meet with Chavez.[3]

History

[edit]Pre-contact

[edit]Indigenous peoples are thought to have inhabited Maine and surrounding areas for at least 11,000 years.[4] They had a hunting-gathering society, with the men hunting beaver, otters, moose, bears, caribou, fish, seafood (clams, mussels, fish), birds, and possibly marine mammals such as seals. The women gathered and processed bird eggs, berries, nuts, and roots, all of which were found locally.[5]

People on the present-day Maine coast practiced some agriculture, but not to the same extent as that of Indigenous peoples in southern New England, where the climate was more temperate.[6] Food was potentially scarce only toward the end of the winter, in February and March. For the rest of the year, the Penobscot and other Wabanaki likely had little difficulty surviving because the land and ocean waters offered much bounty, and the number of people was sustainable.[5] The bands moved seasonally, following the patterns of game and fish.

Contact and colonization

[edit]

During the 16th century the Penobscot had contact with Europeans through the fur trade. It was lucrative and the Penobscot were willing to trade pelts for European goods such as metal axes, guns, and copper or iron cookware. Hunting for fur pelts reduced the game, however, and the European trade introduced alcohol to Penobscot communities for the first time. It has been argued that the people are genetically vulnerable to alcoholism, a racist sentiment with no evidence which Europeans frequently tried to exploit in dealings and trade. Penobscot people and other nations made pine beer, which had vitamin C; in addition to being an alcoholic beverage, it had the benefit of allaying the onset of scurvy.

When European colonizers arrived, they brought alcohol in quantity. Europeans may have slowly developed enzymes, metabolic processes, and social mechanisms for dealing with a normalized high intake of alcohol, but Penobscot people, though familiar with alcohol, had never had access to the gross quantity of alcohol that Europeans offered.

The Europeans carried endemic infectious diseases of Eurasia to the Americas, and the Penobscot had no acquired immunity. Their fatality rates from the introduction of measles, smallpox and other infectious diseases was high. The population also declined due to further encroachment by settlers who cut off access to the Penobscot's main food source of running fish through the process of damming the Penobscot River, the loss of big game through the process of clear cutting of forests for the logging industry and through massacres carried out by settlers. This catastrophic population depletion may have contributed to Christian conversion (among other factors); the people could see that the European priests did not suffer from the pandemics. The latter said that the Penobscot had died because they did not believe in Jesus Christ.[5]

At the beginning of the 17th century, Europeans began to live year-round in Wabanaki territory.[5] At this time, there were probably about 10,000 Penobscot (a number which fell to below 500 by the early 19th century).[7] As contact became more permanent, after about 1675, conflicts arose through differences in cultures, conceptions of property, and competition for resources. Along the Atlantic Coast in present-day Canada, most settlers were French; in New England they were generally English speaking.

The Penobscot sided with the French during the French and Indian War in the mid-18th century (the North American front of the Seven Years' War) after British colonists demanded the Penobscot join their side or be considered hostile. In 1755, governor of Massachusetts Spencer Phips placed a scalp bounty on Penobscot.[8] With a smaller population and greater acceptance of intermarriage, the French posed a lesser threat to the Penobscots' land and way of life.[5]

After the French defeat in the Battle of Quebec in 1759, the Penobscot were left in a weakened position as they had lost their main European ally. During the American Revolution, the Penobscot sided with the Patriots and played an important role in the conflicts which occurred around the border between British Canada and the United States. Despite this the new American government did not seem to recognize their contributions. Anglo-American settlers continued to encroach on Penobscot lands.[5]

In the following centuries, the Penobscot attempted to make treaties in order to hold on to some form of land, but, because they had no power of enforcement in Massachusetts or Maine, Americans kept encroaching on their lands. From about 1800 onward, the Penobscot lived on reservations, specifically, Indian Island, which is an island in the Penobscot River near Old Town, Maine. The Maine state government appointed a Tribal Agent to oversee the tribe. The government believed that they were helping the Penobscot, as stated in 1824 by the highest court in Maine that "...imbecility on their parts, and the dictates of humanity on ours, have necessarily prescribed to them their subjection to our paternal control."[5] This sentiment of "imbecility" set up a power dynamic in which the government treated the Penobscot as wards of the state and decided how their affairs would be managed. The government treated as charitable payments those Penobscot funds derived from land treaties and trusts, which the state had control over and used as it saw fit.[5]

Land claims

[edit]

In 1790, the young United States government enacted the Nonintercourse Act, which stated that the transfer of reservation lands to non-tribal members had to be approved by the United States Congress. Between the years of 1794 and 1833, the Penobscot and Passamaquoddy tribes ceded the majority of their lands to Massachusetts (then to Maine after it became a state in 1820) through treaties that were never ratified by the US Senate and that were illegal under the constitution, as only the federal government had the power to make such treaties. They were left only the Penobscot Indian Island Reservation.

In the 1970s, at a time of increasing assertions of sovereignty by Native Americans, the Penobscot Nation sued the state of Maine for land claims, calling for some sort of compensation in the form of land, money, and autonomy for the state's violation of the Nonintercourse Act in the 19th century. The disputed land accounted for 60% of all of the land in Maine, and 35,000 people (the vast majority of whom were not tribal members) lived in the disputed territory.

The Penobscot and the state reached a settlement, Maine Indian Claims Settlement Act (MICSA), in 1980, resulting in an $81.5-million-dollar settlement that the Penobscot could use to acquire more tribal land. The terms of the settlement provided for such acquisition, after which the federal government would hold some of this land in trust for the tribe, as is done for reservation land. The tribe could also purchase other lands in the regular manner. The act established the Maine Indian Tribal-State Commission, whose function was to oversee the effectiveness of the Act and to intervene in certain areas such as fishing rights, etc. in order to settle disputes between the state and the Penobscot or Passamaquoddy.[9]

Because it is a federally recognized sovereign nation with direct relations with the federal government, the Penobscot have disagreed with state assertions that it has the power to regulate hunting and fishing by tribal members. The Nation filed suit against the state in August 2012, contending in Penobscot Nation v. State of Maine, that the 1980 MICSA settlement gave the Nation jurisdiction and regulatory authority over hunting and fishing in the "Main Stem" of the Penobscot River as well as on its reservation.[10]

At the request of the Nation, the US Department of Justice has joined the suit on behalf of the tribe. In addition, in an unprecedented step, five members of the Congressional Native American Caucus representing other jurisdictions filed an amici curiae brief in support of the Penobscot in this case. In addition to its reservation, the Nation owns islands in the river extending 60 mi (97 km) upriver; it also acquired hundreds of thousands of acres of land elsewhere in the state, as a result of the 1980 settlement of its land claim. Some analysts predict that this case will be as significant to Indian law and sovereignty as the fishing rights cases of Native American tribes in the Pacific Northwest in the 1970s, which resulted in the 1974 Boldt decision affirming their rights to fishing and hunting in their former territories.[10] The five members of the Congressional Native American Caucus who filed are Betty McCollum (D-MN), co-chair of the Congressional Native American Caucus with Tom Cole (R-OK) (Chickasaw); Raúl Grijalva, (D-AZ), vice chair of the Congressional Native American Caucus; Ron Kind (D-WI), vice chair of the Congressional Native American Caucus; and Ben Ray Luján (D-NM), vice chair of the Congressional Native American Caucus.

Language

[edit]Penobscot people historically spoke a dialect of Eastern Abenaki, an Algonquian language. It is very similar to the languages of the other members of the Wabanaki Confederacy. There are no fluent speakers and the last known Penobscot speaker of Eastern Abenaki, Madeline Tower Shay,[11] died in the 1990s. A dictionary was compiled by Frank Siebert.[12] The elementary school and the Boys and Girls Club on Indian Island are making an effort to reintroduce the language by teaching it to the children.[13] The written Penobscot language was developed with a modified Roman alphabet; distinct characters have been developed to represent sounds that do not exist in the Roman alphabet.[14][12]

In 1643, Roger Williams wrote A Key into the Language of America. In this work, Williams explained that the language of the Narragansett people (and tribes they'd overtaken or forced into submission) used a language differing only from the northern Algonquian people, in dialect. He wrote that if one tribe's language was known, communication with the other tribe was possible; this was the case all the way north to remote areas of Labrador. Natives in Labrador spoke Algonquian and the Labrador neighbors were of same linguistic stock as the Narragansett tribe. (Williams wrote that this was not the case with the drastically different Iroquois language.) Fluent in many languages, Williams had lived with native people to improve his native language skill before embarking on missionary work and authoring prayer conversion booklets. His opinion, Williams wrote, was that the Narragansett (hence the Algonquian) in many cases had words that were Hebrew or in a few cases Greek that he recognized from his work in old Hebrew and Greek biblical text translations. His book A Key into the Language of America includes a phonetic English dictionary that Williams wished to publish so that his knowledge of this Native American language would not die with him.[15]

The Penobscot smear the sap of Abies balsamea over sores, burns, and cuts.[16]

Visual art

[edit]

Baskets

[edit]The Penobscot traditionally made baskets out of sweet grass, brown ash, and birch bark. These materials grow in wetlands throughout Maine. However, the species are threatened due to habitat destruction and the emerald ash borer. This insect threatens to destroy all ash trees in Maine, much as it already has devastated ash forests in the Midwest.

The baskets were traditionally made for practical use, but after European contact, the Penobscot began making "fancy baskets" for trade with the Europeans. Basket-making is traditionally a woman's skill passed down in families. Many members of the tribe have been learning traditional forms and creating new variations.[17]

Birchbark canoes

[edit]The birch bark canoe was at one time an important mode of transportation for all nations of the Wabanaki Confederacy. Each nation makes a characteristic shape of canoe. The vessels are each made from one piece of bark from a white birch tree. If done correctly, the large piece of bark can be removed without killing the tree.[18]

Spirituality

[edit]The Penobscot have a rich history of connection to the land and all of its bounties in Maine which is apparent in their folklore and reverence towards all things. Their rich spiritual cosmology informs their efforts of preserving land and natural resources in their sacred homeland. The landscapes of Maine are extremely valuable to the survival and beliefs of the Penobscot; their namesake river is personified, and most dear to them. Annette Kolodny describes "how deeply rooted the Penobscot cosmology is within the Maine landscape; their ethic of mutual obligation to a land full of spirits, animal-people, and daunting power is fundamentally geographic, every place name helping to orient a traveler in relation to both physical space and spiritual power."[19]

Their reverence is also based on their cosmology starting with their origin story where Klose-kur-beh (Gluskbe) is the central character. Klose-kur-beh provides the Penobscot with "spiritual knowledge" and "practical knowledge (like how to construct a canoe)" as well instilling their "ethical precepts through" twelve 'episodes' which instill the importance of each unique value.[20] Klose-kur-beh provides humans and animals with practical skills needed to thrive in the unforgiving climate of the North East and punishes those who operated outside of his code. Since Klose-kur-beh dates back to creation, according to Penobscot cosmology he was aware of other races and warned of the arrival of the white man, "What makes the white man dangerous is the lethal combination of his greed ('he [. . .] wanted the whole earth') and his lust for power ('he wants the power over all the earth'). That combination leads him to 'reach forth his hand to grasp all things for his comfort' and, in the process, virtually destroy the world".[20] This warning from such a prominent figurehead in Penobscot beliefs highlights that they upheld the values of preservation and protection of Maine's land and ecological resources.

The French missionaries converted many Penobscot people to Christianity. In the 21st century, some members practice traditional spirituality; others on Indian Island are Catholic or Protestant.[5]

Nature

[edit]Through their folklore, the Penobscot are taught "that the plants and animals were their helpers and companions, just as the people, in their turn, were to act as kin and companions to the living world around them.... Such stories embed their listeners in a universe of mutually interacting and intimate reciprocal relationships."[20] This starkly contrasts the European view which saw the land as something to be owned and commodified, highlighting the need for advocacy to improve and protect the culture and land of the Penobscot.

Gambling

[edit]In 1973 the nation opened Penobscot High Stakes Bingo on Indian Island. This was one of the first commercial gambling operations on a reservation in the United States. Bingo is open one weekend every six weeks. The Penobscot tribe has pushed for state legislation allowing them to add slot machines to their bingo hall, which has been granted.[21]

In popular culture

[edit]The climax of the 1825 novel Brother Jonathan by Maine native John Neal is set on Indian Island during the American Revolutionary War. The novel features a protagonist of mixed Penobscot-English descent and describes the island as "the last encampment of the Penobscot Red men".[22]

Notable Penobscot

[edit]- Maulian Bryant, first Penobscot tribal ambassador, daughter of former chief Barry Dana.

- Donna M. Loring, author, broadcaster, and tribal representative of the Penobscot

- Madockawando, a sachem, led his people against the English settlers during King William's War

- Sherri Mitchell, an attorney, author, teacher and activist

- Wayne Mitchell, politician, was elected by the Penobscot Tribe of Maine to serve as a non-voting tribal representative to the Maine House of Representatives

- Horace Nelson, political leader and the father of dancer and actress Molly Spotted Elk

- Old John Neptune, medicine man and tribal leader mentioned by Henry David Thoreau

- Joseph Nicolar, Tribal Representative to Maine Legislature and celebrated author of The Life and Traditions of the Red Man (1893)

- Joseph Orono, sachem who urged his tribesmen to side with the Americans against the English

- Lucy Nicolar Poolaw, entertainer billed as "Princess Watahwaso", businesswoman, and activist

- Darren Ranco, anthropologist at the University of Maine

- June Sapiel, activist

- Rebecca Sockbeson, Wabanaki scholar, activist, and associate professor at the University of Alberta

- Theresa Secord, artist, basketmaker, geologist and activist, related to Horace Nelson

- Charles Norman Shay, a Penobscot Tribal Elder and decorated (Bronze Star, Silver Star, Légion d'honneur) veteran of both World War II and the Korean War.[23]

- Andrew Sockalexis, a marathon runner who competed in the 1912 Stockholm Olympics, inducted into the Maine Running Hall of Fame in 1989[24]

- Louis Sockalexis, the first Native American to play in major league baseball (Cleveland Guardians).

- Molly Spotted Elk (Mary Alice "Molly Dellis" Nelson Archambaud), 1903–1977, internationally known dancer who starred in the classic film, The Silent Enemy[25]

- ssipsis, poet, social worker, visual artist, writer, editor and storyteller, her work was focused on and inspired by the advancement of Indigenous peoples

- Kiayaun Williams-Clark, American actor most notably from Saints of Newark, Power, and Guild

- Carla Knapp, National Vice President of Native Services, Boys & Girls Clubs of America

Many Penobscots moved to urban areas around the World War II era to Boston, Connecticut, New York City, New Jersey, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh; and the Cleveland, Ohio area to settled in the West Side (of the Cuyahoga River) or "Cuyahoga" neighborhood; and in Baltimore and Washington DC.

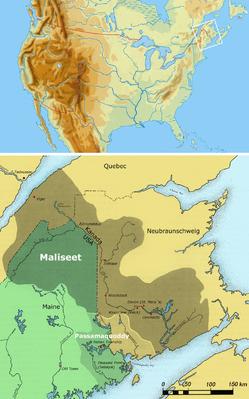

Maps

[edit]Maps showing the approximate locations of areas occupied by members of the Wabanaki Confederacy (from north to south):

-

Eastern Abenaki (Penobscot, Kennebec, Arosaguntacook, Pigwacket/Pequawket)

-

Western Abenaki (Arsigantegok, Missisquoi, Cowasuck, Sokoki, Pennacook

See also

[edit]- Maine Wabanaki-State Truth and Reconciliation Commission

- Maine penny

- Penobscot Building

- St. Anne's Church and Mission Site

- Joint Tribal Council of the Passamaquoddy Tribe v. Morton

References

[edit]- ^ "Penobscot Indian Nation". US Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved 30 August 2012.

- ^ a b "Tribal Directory". National Congress of American Indians. Retrieved 30 August 2012.

- ^ "Penobscot Nation's relationship with Hugo Chavez". Bangor Daily News. 6 March 2013. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- ^ The Wabanakis of Maine and the Maritimes. American Friends Service Committee, 1989.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Wabanakis of Maine and the Maritimes[full citation needed]

- ^ Sr, Francis; Eric, James (2008). "Burnt Harvest: Penobscot People and Fire". Maine History. 44 (1): 4–18.

- ^ "History", Penobscot Nation.

- ^ Phips Bounty Proclamation

- ^ Scully, Diana (14 February 1995). "Maine Indian Claims Settlement: Concepts, Context, and Perspectives". Indian Tribal-State Commission Documents. The Maine Indian Tribal-State Commission.

- ^ a b Gale Courey Toensing, "Congress Members Support 'Penobscot v. Maine' in Unprecedented Court Filing.", Indian Country Today, 5 May 2015, accessed 5 May 2015

- ^ "Abnaki, Eastern". Ethnologue. Retrieved 30 August 2012.

- ^ a b Gregory, Alice (2021-04-12). "How Did a Self-Taught Linguist Come to Own an Indigenous Language?". The New Yorker. Retrieved 2021-06-29.

- ^ "Penobscot Nation Boys & Girls Club". penobscotnation.org. Retrieved 14 January 2011.

- ^ "Indian Island School". Archived from the original on 2009-10-12. Retrieved 2009-08-05.

- ^ A Key into the Language of America. Roger Williams & Howard Chapin. 1643 Gregory Dexter,London. Publisher,

- ^ Speck, Frank G. (December 1917). Medicine Practices of the Northeastern Algonquians. Proceedings of the nineteenth International congress of Americanists. pp. 303–321.

- ^ "Penobscot Nation". www.penobscotnation.org. Retrieved 5 July 2017.

- ^ "Penobscot River Restoration Project - Birch Bark Canoe". www.penobscotriver.org. 25 September 2013. Archived from the original on 8 March 2012. Retrieved 5 July 2017.

- ^ Kucich, John J. (2011). "Lost in the Maine Woods: Henry David Thoreau, Joseph Nicolar, and the Penobscot World". The Concord Saunterer. 19/20: 22–52. JSTOR 23395210.

- ^ a b c Kolodny, Annette (2007). "Rethinking the 'Ecological Indian': A Penobscot Precursor". Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment. 14 (1): 1–23. doi:10.1093/isle/14.1.1. JSTOR 44086555.

- ^ "Townsquare Interactive". penobscotbingo.com. Retrieved 5 July 2017.

- ^ Richards, Irving T. (1933). The Life and Works of John Neal (PhD thesis). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University. pp. 685–686. OCLC 7588473.

- ^ "Charles N. Shay". Archived from the original on 2015-04-02. Retrieved 2015-03-24.

- ^ "History3.gif". Archived from the original on 2007-02-23. Retrieved 2006-12-23.

- ^ See McBride, Bunny. 1995. Molly Spotted Elk: A Penobscot in Paris. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press

External links

[edit]- Penobscot Indian Nation, official website

- "The Ancient Penobscot, or Panawanskek". Historical Magazine, February 1872

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Penobscot Bingo

- Entirely by hand... from the ground up, Tom Hennessey" Archived 2008-08-20 at the Wayback Machine, Bangor Daily News

- Wabanaki Ethnography, National Park Service

- Harrison, Judy. "Indian Reservation Priests Follow a 300 year old tradition", Bangor Daily News

- Indian Treaties