Royal charter

| Part of the Politics series |

| Monarchy |

|---|

|

|

|

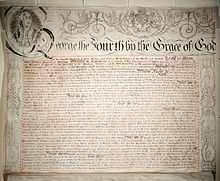

A royal charter is a formal grant issued by a monarch under royal prerogative as letters patent. Historically, they have been used to promulgate public laws, the most famous example being the English Magna Carta (great charter) of 1215, but since the 14th century have only been used in place of private acts to grant a right or power to an individual or a body corporate.[1][2][3] They were, and are still, used to establish significant organisations such as boroughs (with municipal charters), universities, and learned societies.

Charters should be distinguished from royal warrants of appointment, grants of arms, and other forms of letters patent, such as those granting an organisation the right to use the word "royal" in their name or granting city status, which do not have legislative effect.[4][5][6][7] The British monarchy has issued over 1,000 royal charters.[5] Of these about 750 remain in effect.

The earliest charter recorded on the UK government's list was granted to the University of Cambridge by Henry III of England in 1231,[8] although older charters are known to have existed including to the Worshipful Company of Weavers in England in 1150[9] and to the town of Tain in Scotland in 1066.[10] Charters continue to be issued by the British Crown, a recent example being that awarded to the Chartered Institute of Legal Executives (CILEX), and the Chartered Institute of Ergonomics and Human Factors, in 2014.[11]

Historical development

[edit]Charters have been used in Europe since medieval times to grant rights and privileges to towns, boroughs, and cities. During the 14th and 15th centuries the concept of incorporation of a municipality by royal charter evolved.[12] Royal charters were used in England to make the most formal grants of various rights, titles, etc. until the reign of Henry VIII, with letters patent being used for less solemn grants. After the eighth year of Henry VIII, all grants under the Great Seal were issued as letters patent.[13]

Among the past and present groups formed by royal charter are the Company of Merchants of the Staple of England (13th century), the British East India Company (1600), the Hudson's Bay Company, the Chartered Bank of India, Australia and China (since merged into Standard Chartered), the Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation Company (P&O), the British South Africa Company, and some of the former British colonies on the North American mainland, City livery companies, the Bank of England and the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC; see BBC Charter).[14]

Corporations

[edit]Between the 14th and 19th centuries, royal charters were used to create chartered companies – for-profit ventures with shareholders, used for exploration, trade, and colonisation. Early charters to such companies often granted trade monopolies, but this power was restricted to Parliament from the end of the 17th century.[15] Until the 19th century, royal charters were the only means other than an act of parliament by which a company could be incorporated; in the UK, the Joint Stock Companies Act 1844 opened up a route to incorporation by registration, since when incorporation by royal charter has been, according to the Privy Council, "a special token of Royal favour or ... a mark of distinction".[5][16][17]

The use of royal charters to incorporate organisations gave rise to the concept of the "corporation by prescription". This enabled corporations that had existed from time immemorial to be recognised as incorporated via the legal fiction of a "lost charter".[18] Examples of corporations by prescription include Oxford and Cambridge universities.[19][20]

Universities and colleges

[edit]According to the Catholic Encyclopedia, of the 81 universities established in pre-Reformation Europe, 13 were established ex consuetudine without any form of charter, 33 by Papal bull alone, 20 by both Papal bull and imperial or royal charter, and 15 by imperial or royal charter alone. Universities established solely by royal (as distinct from imperial) charter did not have the same international recognition – their degrees were only valid within that kingdom.[21]

The first university to be founded by charter was the University of Naples in 1224, founded by an imperial charter of Frederick II. The first university founded by royal charter was the University of Coimbra in 1290, by King Denis of Portugal, which received papal confirmation the same year. Other early universities founded by royal charter include the University of Perpignan (1349; papal confirmation 1379) and the University of Huesca (1354; no confirmation), both by Peter IV of Aragon; the Jagiellonian University (1364; papal confirmation the same year) by Casimir III of Poland; the University of Vienna (1365; Papal confirmation the same year) by Rudolf IV, Duke of Austria; the University of Caen (1432; Papal confirmation 1437) by Henry VI of England; the University of Girona (1446; no confirmation) and the University of Barcelona (1450; papal confirmation the same year), both by Alfonso V of Aragon; the University of Valence (1452; papal confirmation 1459) by the Dauphin Louis (later Louis XI of France); and the University of Palma (1483; no confirmation) by Ferdinand II of Aragon.[22]

British Isles

[edit]Both Oxford and Cambridge received royal charters during the 13th century. However, these charters were not concerned with academic matters or their status as universities but rather about the exclusive right of the universities to teach, the powers of the chancellors' courts to rule on disputes involving students, and fixing rents and interest rates.[23][24]

The University of Cambridge was confirmed by a papal bull in 1317 or 1318,[25] but despite repeated attempts, the University of Oxford never received such confirmation.[22] The three pre-Reformation Scottish universities were all established by papal bulls: St Andrews in 1413; Glasgow in 1451; and King's College, Aberdeen (which later became the University of Aberdeen) in 1494.[26]

Following the Reformation, establishment of universities and colleges by royal charter became the norm. The University of Edinburgh was founded under the authority of a royal charter granted to the Edinburgh town council in 1582 by James VI as the "town's college". Trinity College Dublin was established by a royal charter of Elizabeth I (as Queen of Ireland) in 1593. Both of these charters were given in Latin.[27]

The Edinburgh charter gave permission for the town council "to build and to repair sufficient houses and places for the reception, habitation and teaching of professors of the schools of grammar, the humanities and languages, philosophy, theology, medicine and law, or whichever liberal arts which we declare detract in no way from the aforesaid mortification" and granted them the right to appoint and remove professors.[28] But, as concluded by Edinburgh's principal, Sir Alexander Grant, in his tercentenary history of the university, "Obviously this is no charter founding a university".[29] Instead, he proposed, citing multiple pieces of evidence, that the surviving charter was original granted alongside a second charter founding the college, which was subsequently lost (possibly deliberately).[30] This would also explain the source of Edinburgh's degree awarding powers, which were used from the foundation of the college.[31]

The royal charter of Trinity College Dublin, while being straightforward in incorporating the college, also named it as "mother of a University", and rather than granting the college degree-awarding powers stated that "the students on this College ... shall have liberty and power to obtain degrees of Bachelor, Master, and Doctor, at a suitable time, in all arts and faculties".[32] Thus the University of Dublin was also brought into existence by this charter, as the body that awards the degrees earned by students at Trinity College.[33][34]

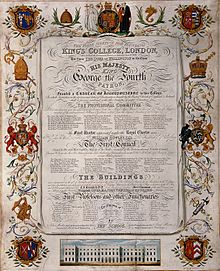

Following this, no surviving universities were created in the British Isles until the 19th century. The 1820s saw two colleges receive royal charters: St David's College, Lampeter in 1828 and King's College London in 1829. Neither of these were granted degree-awarding powers or university status in their original charters. The 1830s saw an attempt by University College London to gain a charter as a university and the creation by Act of Parliament of Durham University, but without incorporating it or granting any specific powers. These led to debate about the powers of royal charters and what was implicit to a university.

The essence of the debate was firstly whether the power to award degrees was incidental to the creation of a university or needed to be explicitly granted and secondly whether a royal charter could, if the power to award degrees was incidental, limit that power – UCL wishing to be granted a royal charter as "London University" but excluding the power to award degrees in theology due to the secular nature of the institute. Sir Charles Wetherell, arguing against the grant of a royal charter to UCL before the Privy Council in 1835, argued for degree-awarding powers being an essential part of a university that could not be limited by charter.[35] Sir William Hamilton, wrote a response to Wetherell in the Edinburgh Review, drawing in Durham University and arguing that the power of universities, including the power to award specific degrees, had always been explicitly granted historically, thus creating a university did not implicitly grant degree-awarding powers.[36] Other historians, however, disagree with Hamilton on the point of whether implicit grants of privileges were made, particularly with regard to the ius ubique docendi – the important privilege of granting universally-recognised degrees that was the defining mark of the studium generale. Hastings Rashdall states that "the special privilege of the jus ubique docendi ... was usually, but not quite invariably, conferred in express terms by the original foundation-bulls; and was apparently understood to be involved in the mere act of erection even in the rare cases where it is not expressly conceded".[37] Similarly, Patrick Zutshi, Keeper of Manuscripts and University Archives in Cambridge University Library, writes that "Cambridge never received from the papacy an explicit grant of the ius ubique docendi, but it is generally considered that the right is implied in the terms of John XXII's letter of 1318 concerning Cambridge's status as a studium generale."[38]

UCL was incorporated by royal charter in 1836, but without university status or degree-awarding powers, which went instead to the University of London, created by royal charter with the explicit power to grant degrees in Arts, Law, and Medicine. Durham University was incorporated by royal charter in 1837 (explicitly not founding the university, which it describes as having been "established under our Royal sanction, and the authority of our Parliament") but although this confirmed that it had "all the property, rights, and privileges which ... are incident to a University established by our Royal Charter" it contained no explicit grant of degree-awarding powers.[39] This was considered sufficient for it to award "degrees in all the faculties",[40] but all future university royal charters explicitly stated that they were creating a university and explicitly granted degree-awarding power. Both London (1878) and Durham (1895) later received supplemental charters allowing the granting of degrees to women, which was considered to require explicit authorisation. After going through four charters and a number of supplemental charters, London was reconstituted by Act of Parliament in 1898.[41]

The Queen's Colleges in Ireland, at Belfast, Cork, and Galway, were established by royal charter in 1845, as colleges without degree awarding powers. The Queens University of Ireland received its royal charter in 1850, stating "We do will, order, constitute, ordain and found an University ... and the same shall possess and exercise the full powers of granting all such Degrees as are granted by other Universities or Colleges in the faculties of Arts, Medicine and Law".[42] This served as the degree awarding body for the Queen's Colleges until it was replaced by the Royal University of Ireland.

The royal charter of the Victoria University in 1880 started explicitly that "There shall be and is hereby constituted and founded a University" and granted an explicit power of awarding degrees (except in medicine, added by supplemental charter in 1883).[43]

From then until 1992, all universities in the United Kingdom were created by royal charter except for Newcastle University, which was separated from Durham via an Act of Parliament. Following the independence of the Republic of Ireland, new universities there have been created by Acts of the Oireachtas (Irish Parliament). Since 1992, most new universities in the UK have been created by Orders of Council as secondary legislation under the Further and Higher Education Act 1992, although granting degree-awarding powers and university status to colleges incorporated by royal charter is done via an amendment to their charter.

United States

[edit]Several of the colonial colleges that predate the American Revolution are described as having been established by royal charter. Except for The College of William & Mary, which received its charter from King William III and Queen Mary II in 1693 following a mission to London by college representatives, these were either provincial charters granted by local governors (acting in the name of the king) or charters granted by legislative acts from local assemblies.[44]

The first charters to be issued by a colonial governor on the consent of their council (rather than by an act of legislation) were those granted to Princeton University (as the College of New Jersey) in 1746 (from acting governor John Hamilton) and 1748 (from Governor Jonathan Belcher). There was concern as to whether a royal charter given by a governor in the King's name was valid without royal approval. An attempt to resolve this in London in 1754 ended inconclusively when Henry Pelham, the prime minister, died. However, Princeton's charter was never challenged in court prior to its ratification by the state legislature in 1780, following the US Declaration of Independence.[45]

Columbia University received its royal charter (as King's College) in 1754 from Lieutenant Governor James DeLancey of New York, who bypassed the assembly rather than risking it rejecting the charter.[46] Rutgers University received its (as Queen's College) in 1766 (and a second charter in 1770) from Governor William Franklin of New Jersey,[47] and Dartmouth College received its in 1769 from Governor John Wentworth of New Hampshire.[48] The case of Dartmouth College v. Woodward, heard before the Supreme Court of the United States in 1818, centred on the status of the college's royal charter.[49] The court found in 1819 that the charter was a contract under the Contract Clause of the US Constitution, meaning that it could not be impaired by state legislation, and that it had not been dissolved by the revolution.[50]

The charter for the College of William and Mary specified it to be a "place of universal study, or perpetual college, for divinity, philosophy, languages and other good arts and sciences", but made no mention of the right to award degrees.[51] However, the Latin text of the charter uses studium generale – the technical term used in the Middle Ages for a university –where the English text has "place of universal study"; it has been argued that this granted William and Mary the rights and status of a university.[52]

The Princeton charter, however, specified that the college could "give and grant any such degree and degrees ... as are usually granted in either of our universities or any other college in our realm of Great Britain".[53] Columbia's charter used very similar language a few years later,[54] as did Dartmouth's charter.[55] The charter of Rutger uses quite different words, specifying that it may "confer all such honorary degrees as usually are granted and conferred in any of our colleges in any of our colonies in America".[56]

Of the other colleges founded prior to the American Revolution, Harvard College was established in 1636 by Act of the Great and General Court of the Massachusetts Bay Colony and incorporated in 1650 by a charter from the same body,[57] Yale University was established in 1701 by Act of the General Assembly of Connecticut,[58] the University of Pennsylvania received a charter from the proprietors of the colony in 1753,[59] Brown University was established in 1764 (as the College of Rhode Island) by an Act of the Governor and General Assembly of Rhode Island,[60] and Hampden-Sydney College was established privately in 1775 but not incorporated until 1783.[61]

Canada

[edit]Eight Canadian universities and colleges were founded or reconstituted under royal charters in the 19th century, prior to Confederation in 1867. Most Canadian universities originally established by royal charter were subsequently reincorporated by acts of the relevant parliaments.[62]

The University of King's College was founded in 1789 and received a royal charter in 1802, naming it, like Trinity College, Dublin, "the Mother of an University" and granting it the power to award degrees.[63][64] The charter remains in force.[65]

McGill University was established under the name of McGill College in 1821, by a provincial royal charter issued by Governor General of British North America the Earl of Dalhousie; the charter stating that the "College shall be deemed and taken to be an University" and should have the power to grant degrees.[66] It was reconstituted by a royal charter issued in 1852 by Queen Victoria, which remains in force.[67]

The University of New Brunswick was founded in 1785 as the Academy of Liberal Arts and Sciences and received a provincial charter as the College of New Brunswick in 1800. In the 1820s, it began giving university-level instruction and received a royal charter under the name King's College as a "College, with the style and privileges of an University", in 1827. The college was reconstituted as the University of New Brunswick by an act of the provincial parliament in 1859.[68][69]

The University of Toronto was founded by royal charter in 1827, under the name of King's College, as a "College, with the style and privileges of an University", but did not open until 1843. The charter was subsequently revoked and the institution replaced by the University of Toronto in 1849, under provincial legislation.[70] Victoria University, a college of the University of Toronto, opened in 1832 under the name of the Upper Canada Academy, giving "pre-university" classes, and received a royal charter in 1836. In 1841. a provincial act replaced the charter, reconstituted the academy as Victoria College, and granted it degree-awarding powers.[71] Another college of the University of Toronto, Trinity College, was incorporated by an act of the legislature in 1851 and received a royal charter in 1852, stating that it, "shall be a University and shall have and enjoy all such and the like privileges as are enjoyed by our Universities of our United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland".[72]

Queen's University was established by royal charter in 1841. This remains in force as the university's primary constitutional document and was last amended, through the Canadian federal parliament, in 2011.[73]

Université Laval was founded by royal charter in 1852, which granted it degree awarding powers and started that it would, "have, possess, and enjoy all such and the like privileges as are enjoyed by our Universities of our United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland".[74] This was replaced by a new charter from the National Assembly of Quebec in 1971.[75]

Bishop's University was founded, as Bishop's College, by an act of the Parliament of the Province of Canada in 1843 and received a royal charter in 1853, granting it the power to award degrees and stating that, "said College shall be deemed and taken to be a University, and shall have and enjoy all such and the like privileges as are enjoyed by our Universities of our United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland".[76]

The University of Ottawa was established in 1848 as the College of Bytown. It received a royal charter under the name College of Ottawa, raising it to university status in 1866.[77]

Australia

[edit]The older Australian universities of Sydney (1850) and Melbourne (1853) were founded by acts of the legislatures of the colonies. This gave rise to doubts about whether their degrees would be recognised outside of those colonies, leading to them seeking royal charters from London, which would grant legitimacy across the British Empire.[78]

The University of Sydney obtained a royal charter in 1858. This stated that (emphasis in the original):

the Memorialists confidently hope that the Graduates of the University of Sydney will not be inferior in scholastic requirements to the majority of Graduates of British Universities, and that it is desirable to have the degrees of the University of Sydney generally recognised throughout our dominions; and it is also humbly submitted that although our Royal Assent to the Act of Legislature of New South Wales hereinbefore recited fully satisfies the principle of our law that the power of granting degrees should flow from the Crown, yet that as that assent was conveyed through an Act which has effect only in the territory of New South Wales, the Memorialists believe that the degrees granted by the said University under the authority of the said Act, are not legally entitled to recognition beyond the limits of New South Wales; and the Memorialists are in consequence most desirous to obtain a grant from us of Letters Patent requiring all our subjects to recognise the degrees given under the Act of the Local Legislature in the same manner as if the said University of Sydney had been an University established within the United Kingdom under a Royal Charter or an Imperial enactment.

The charter went on to (emphasis in the original):

will, grant and declare that the Degrees of Bachelor of Arts, Master of Arts, Bachelor of Laws, Doctor of Laws, Bachelor of Medicine, and Doctor of Medicine, already granted or conferred or hereafter to be granted or conferred by the Senate of the said University of Sydney shall be recognised as Academic distinctions and rewards of merit and be entitled to rank, precedence, and consideration in our United Kingdom and in our Colonies and possessions throughout the world as fully as if the said Degree had been granted by any University of our said United Kingdom.[79]

The University of Melbourne's charter, issued the following year, similarly granted its degrees equivalence with those from British universities.[80]

The act that established the University of Adelaide in 1874 included women undergraduates, causing a delay in the granting of its charter as the authorities in London did not wish to allow this. A further petition for the power to award degrees to women was rejected in 1878 – the same year that London was granted that authority. A charter was finally granted – admitting women to degrees – in 1881.[81][82]

The last of Australia's 19th century universities, the University of Tasmania, was established in 1890 and obtained a royal charter in 1915.[83]

Guilds, learned societies, and professional bodies

[edit]Guilds and livery companies are among the earliest organisations recorded as receiving royal charters. The Privy Council list has the Saddlers Company in 1272 as the earliest, followed by the Merchant Taylors Company in 1326 and the Skinners Company in 1327. The earliest charter to the Saddlers Company gave them authority over the saddlers trade; it was not until 1395 that they received a charter of incorporation.[84] The Merchant Taylors were similarly incorporated by a subsequent charter in 1408.[85]

Royal charters gave the first regulation of medicine in Great Britain and Ireland. The Barbers Company of London in 1462, received the earliest recorded charters concerning medicine or surgery, charging them with the superintendence, scrutiny, correction, and governance of surgery. A further charter in 1540 to the London Guild – renamed the Company of Barber-Surgeons – specified separate classes of surgeons, barber-surgeons, and barbers. The London Company of Surgeons separated from the barbers in 1745, eventually leading to the establishment of the Royal College of Surgeons by royal charter in 1800.[86] The Royal College of Physicians of London was established by royal charter in 1518 and charged with regulating the practice of medicine in the City of London and within seven miles of the City.[87]

The Barbers Guild (the Gild of St Mary Magdalen) in Dublin is said to have received a charter in 1446, although this was not recorded in the rolls of chancery and was lost in the 18th century. A later charter united the barbers with the (previously unincorporated) surgeons in 1577.[88] The Royal College of Physicians of Ireland was established by royal charter in 1667[89] and the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, which evolved from the Barbers' Guild in Dublin, in 1784.[90]

The Royal Society was established in 1660 as Britain's first learned society and received its first royal charter in 1662. It was reincorporated by a second royal charter in 1663, which was then amended by a third royal charter in 1669. These were all in Latin, but a supplemental charter in 2012 gave an English translation to take precedence over the Latin text.[91] The Royal Society of Edinburgh was established by royal charter in 1783 and the Royal Irish Academy was established in 1785 and received its royal charter in 1786.[92]

New professional bodies were formed in Britain in the early 19th century representing new professions that arose after the industrial revolution and the rise of laissez-faire capitalism. These new bodies sought recognition by gaining royal charters, laying out their constitutions and defining the profession in question, often based on occupational activity or particular expertise. To their various corporate objectives, these bodies added the concept of working in the public interest that was not found in earlier professional bodies. This established a pattern for British professional bodies, and the 'public interest' has become a key test for a body seeking a royal charter.[93]

Australia

[edit]Royal charters have been used in Australia to incorporate non-profit organisations. However, since at least 2004 this has not been a recommended mechanism.[94]

Belgium

[edit]The royal decree is the equivalent in Belgium of a royal charter. In the period before 1958, 32 higher education institutes had been created by royal charter. These were typically engineering or technical institutions rather than universities.[95]

However, several non-technical higher education institutions have been founded, or refounded, under royal decree, such as the Fonds de la Recherche Scientifique (National Fund for Scientific Research) in 1928[96] and the Koninklijke Vlaamse Academie van België voor Wetenschappen en Kunsten in 1938.[97]

Since the Belgian state reform of 1988–1989, competency over education was transferred to the federated entities of Belgium. Royal decrees can therefore no longer grant higher education institution status or university status.[98]

Canada

[edit]

In Canada, there are a number of organisations that have received royal charters. However, the term is often applied incorrectly to organisations, such as the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, that have been granted the use of a royal title rather than a royal charter.[99]

Companies and societies

[edit]Companies, corporations, and societies in Canada founded under or augmented by a royal charter include:

- The Canada Company, incorporated by Act of Parliament in June 1825. A royal charter was issued in August 1826 to purchase and develop lands. Purchased the Crown Reserve of 1,384,413 acres and a special grant of 1,100,000 acres in the Huron County area.[100]

- The Literary and Historical Society of Quebec, founded in 1824 as the first learned society in Canada, received its royal charter in 1831.[101]

- The Royal Society of Canada, founded by Act of Parliament and granted a royal charter in 1883.[102]

- The Royal Life Saving Society of Canada, founded 1891 and received royal patronage and style 1904. A royal charter was granted in 1924 by King George V.[103]

British royal chartered corporations operating in Canada:

- The East India Company; granted a royal charter in 1600 by Queen Elizabeth I (tea sales in North America)[100]

- The Hudson's Bay Company; founded by a royal charter issued in 1670 by King Charles II (administration of parts of current Quebec, Northern Ontario, and North West Territories, including Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta, and judicial connections with Upper Canada)[104]

- The Bank of British North America capital raised in Britain, founded by royal charter issued in 1836 (amalgamated with Bank of Montreal 1918).[104]

- The Royal Commonwealth Society; founded by a royal charter issued in 1882 by Queen Victoria[105]

- The Royal Academy of Dance; founded in 1920 as the Association of Teachers of Operatic Dancing; reconstituted by a royal charter issued in 1936 by King George V[106]

- The Boy Scouts Association founded in 1910; incorporated by royal charter in 1912; Canadian General Council, now called Scouts Canada, formed in 1914 and incorporated by Act of the Canadian Parliament in 1914.

Territories and communities

[edit]Cities under royal charter are not subject to municipal Acts of Parliament applied generally to other municipalities, and instead are governed by legislation applicable to each city individually. The royal charter codifies the laws applied to the particular city and lays out the powers and responsibilities not given to other municipalities in the province concerned.[citation needed]

- St. John's; claimed as England's first oversea colony by royal charter issued in 1583 by Queen Elizabeth I

- Nova Scotia; founded by a royal charter issued in 1621 by King James I[107]

- Saint John; founded by a royal charter issued in 1785 by King George III[108]

- Vancouver

- Winnipeg

- Montreal[109]

India

[edit]The Institution of Engineers was incorporated by royal charter in 1935.[110]

Ireland

[edit]A number of Irish institutions were established by or received royal charters prior to Irish independence. These are no longer under the jurisdiction of the British Privy Council and their charters can thus only be altered by a Charter or Act of the Oireachtas (Irish Parliament).[33]

South Africa

[edit]The University of South Africa received a royal charter in 1877.[111] The Royal Society of South Africa received a royal charter in 1908.[112]

United Kingdom

[edit]Royal charters continue to be used in the United Kingdom to incorporate charities and professional bodies, to raise districts to borough status, and to grant university status and degree awarding powers to colleges previously incorporated by royal charter.[citation needed]

Most new grants of royal charters are reserved for eminent professional bodies, learned societies, or charities "which can demonstrate pre-eminence, stability and permanence in their particular field".[113] The body in question has to demonstrate not just pre-eminence and financial stability but also that bringing it under public regulation in this manner is in the public interest.[114] In 2016, the decision to grant a royal charter to the (British) Association for Project Management (APM) was challenged in the court by the (American) Project Management Institute (PMI), who feared it would give a competitive advantage to APM and claimed the criteria had not been correctly applied; the courts ruled that while the possibility of suffering a competitive disadvantage did give PMI standing to challenge the decision, the Privy Council was permitted to take the public interest (in having a chartered body promoting the profession of project management) into account as outweighing any failure to meet the criteria in full.[115] A list of UK chartered professional associations is at List of professional associations in the United Kingdom § Chartered.

Individual chartered designations, such as chartered accountant or chartered engineer, are granted by some chartered professional bodies to individual members that meet certain criteria. The Privy Council's policy is that all chartered designations should be broadly similar, and most require Master's level qualifications (or similar experience).[116]

In January 2007, the UK Trade Marks Registry refused to grant protection to the American Chartered Financial Analyst trademark, as the word "chartered" in the UK is associated with royal charters, thus its use would be misleading.[117] "Charter" and "chartered" continue to be "sensitive words" in company names, requiring evidence of a royal charter or (for "chartered") permission from a professional body operating under royal charter.[118] The use of "chartered" in a collective trade mark similarly requires the association applying for the mark to have a royal charter as otherwise "the mark would mislead the public into believing that the association and its members have chartered status".[119]

Unlike other royal charters, a charter to raise a district to borough status is issued using statutory powers under the Local Government Act 1972 rather than by the royal prerogative.[116]

The company registration number of a corporation with a royal charter is prefixed by "RC" for companies registered in England and Wales, "SR" for companies registered in Scotland, and "NR" for companies registered in Northern Ireland.[120] However, many chartered corporations from outside England have an RC prefix from when this was used universally.[citation needed]

The BBC operates under a royal charter which lasts for a period of ten years, after which it is renewed.[citation needed]

United States

[edit]Royal charters have not been issued in the US since independence. Those that existed prior to that have the same force as other charters of incorporation issued by state or colonial legislatures. Following Dartmouth College v. Woodward, they are "in the nature of a contract between the state, the corporation representing the founder, and the objects of the charity". Case law indicates that they cannot be changed by legislative action in a way that impairs the original intent of the founder, even if the corporation consents.[121]

See also

[edit]- Congressional charter, equivalent document in the United States

References

[edit]- ^ "Charter". The Supplement to the Penny Cyclopaedia of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. Vol. 1. Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. 1845. pp. 331–332. Archived from the original on 22 August 2024. Retrieved 4 February 2019.

- ^ "Magna Carta 1215". British Library. Archived from the original on 3 October 2022. Retrieved 3 February 2019.

- ^ Peter Crooks (July 2015). "Exporting Magna Carta: exclusionary liberties in Ireland and the world". History Ireland. 23 (4). Archived from the original on 1 January 2023. Retrieved 4 February 2019.

- ^ "Granting arms". College of Arms. Archived from the original on 7 September 2023. Retrieved 3 February 2019.

- ^ a b c "Royal Charters". Privy Council. Archived from the original on 14 October 2011. Retrieved 31 December 2023.

- ^ "Guidance: Applications for Protected Royal Titles" (PDF). royal.uk. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 May 2017. Retrieved 3 February 2019.

- ^ "Chelmsford to receive Letters Patent granting city status". BBC News. 6 June 2012. Archived from the original on 1 January 2023. Retrieved 4 February 2019.

- ^ "List of chartered bodies". Privy Council. Archived from the original on 25 January 2019. Retrieved 30 January 2019.

- ^ "Guide to the Worshipful Company of Weavers Charter 1707". University of Chicago. Archived from the original on 1 February 2023. Retrieved 30 January 2019.

- ^ "History and Heritage". Visit Tain. Archived from the original on 30 January 2019. Retrieved 30 January 2019.

- ^ "CIEHF Documents". The Chartered Institute of Ergonomics and Human Factors. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 3 February 2019.

- ^ British Borough Charters. Cambridge University Press. 1923. pp. 25–26.

- ^ "Royal grants in letters patent and charters from 1199". The National Archive. Archived from the original on 25 September 2022. Retrieved 14 July 2022.

- ^ BBC Trust | Charter and Agreement Archived 19 May 2022 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ James Bohun (1993). "Protecting Prerogative: William III and the East India Trade Debate, 1689–1698". Past Imperfect: 63–86.

- ^ M. S. Rix (September 1945). "Company Law: 1844 and To-Day". The Economic Journal. 55 (218/219). Wiley/Royal Economic Society: 242–260. doi:10.2307/2226083. JSTOR 2226093.

- ^ "Royal charter". Turcan Connell. Archived from the original on 4 February 2019. Retrieved 3 February 2019.

- ^ John William Willcock (1827). The Law of Municipal Corporations. J.S. Littell. pp. 21–25. Archived from the original on 22 August 2024. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- ^ "Legal status of the University". Statutes and Regulations. University of Oxford. Archived from the original on 4 January 2014. Retrieved 4 February 2019.

- ^ "The University as a charity". University of Cambridge. 21 March 2013. Archived from the original on 16 April 2021. Retrieved 4 February 2019.

- ^ Edward Pace (1912). Universities. Robert Appleton Company. The founders: popes and civil rulers. Archived from the original on 8 June 2020. Retrieved 7 February 2019 – via new adventure.org.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b Osmo Kivinen; Petri Poikus (September 2006). "Privileges of Universitas Magistrorum Et Scolarium and Their Justification in Charters of Foundation from the 13th to the 21st Centuries". Higher Education. 52 (2): 185–213. doi:10.1007/s10734-004-2534-1. JSTOR 29735011. S2CID 143710561.

- ^ David A. Carpenter (2003). The Struggle for Mastery: Britain, 1066–1284. Oxford University Press. p. 463. ISBN 9780195220001. Archived from the original on 22 August 2024. Retrieved 14 July 2022.

- ^ Trevor Henry Aston; Rosamond Faith (1984). "The Endowments of the University and Colleges to circa 1348". In Trevor Henry Aston (ed.). The History of the University of Oxford: The early Oxford schools. Clarendon Press. p. 274. ISBN 9780199510115. Archived from the original on 22 August 2024. Retrieved 14 July 2022.

- ^ James Heywood (1840). "Papal Bull to the University of Cambridge". Collection of Statutes for the University and the Colleges of Cambridge. William Clowes and Sins. p. 45.

- ^ Winifred Bryan Horne (1993). Nineteenth-century Scottish Rhetoric: The American Connection. Southern Illinois University Press. p. 19. ISBN 9780809314706. Archived from the original on 22 August 2024. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- ^ Jos. M. M. Hermans; Marc Nelissen, eds. (2005). Charters of Foundation and Early Documents of the Universities of the Coimbra Group. Leuven University Press. pp. 109–111. ISBN 9789058674746. Archived from the original on 22 August 2024. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- ^ "Charter by King James VI, 14 April 1582". University of Edinburgh. Archived from the original on 28 November 2021. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- ^ Sir Alexander Grant (1884). The Story of the University of Edinburgh During Its First Three Hundred Years. Vol. 1. Longmans, Green, and Company. p. 123. Archived from the original on 22 August 2024. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- ^ Sir Alexander Grant (1884). The Story of the University of Edinburgh During Its First Three Hundred Years. Vol. 1. Longmans, Green, and Company. pp. 107–132. Archived from the original on 22 August 2024. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- ^ Sir Alexander Grant (1884). The Story of the University of Edinburgh During Its First Three Hundred Years. Vol. 1. Longmans, Green, and Company. p. 143. Archived from the original on 22 August 2024. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- ^ "Charter of Queen Elizabeth I" (English; translated from Latin). Trinity College Dublin. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 April 2016. Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- ^ a b "Legal FAQ". Trinity College Dublin. Archived from the original on 28 May 2018. Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- ^ Christopher Palles (1907). "Note by the Lord Chief Baron on the relation between the College and the University". Royal Commission on Trinity College, Dublin, and the University of Dublin: Final Report of the Commissioners. Archived from the original on 22 August 2024. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ^ Charles Wetherell (1834). Substance of the Speech of Sir Charles Wetherell: Before the Lords of the Privy Council, on the Subject of Incorporating the London University. J. G. & F. Rivington. pp. 77–82.

It will be necessary to examine this subject a little more minutely, and particularly with reference to the power of conferring degrees, and the nature of a university. The only place where I can find any legal discussion on matters so little brought under consideration as these, is the argument of Mr. Attorney General Yorke, in Dr. Bentley's case, which is reported in 2nd Lord Raymond, 1345 ... In this proposition of Mr. Yorke two principles are laid down. The first is that 'granting degrees flows from the Crown;' and the second is, that if 'a University be erected, the power of granting degrees is incidental to the grant.' ... The subject matter granted, is the power of covering degrees; an emanation, as Mr. Yorke expresses it, from the Crown. It is the concession of this power that constitutes the direct purpose and the essential character of a University. ... This question of law arises:– How can this anomalous and strange body be constituted in the manner professed? It is to be a 'University,' but degrees in theology it is not to give. But Mr. Attorney-General Yorke tells us, that the power of giving degrees is incidental to the grant. If this be law, is not the power of conferring theological degrees equally incident to the grant, as other degrees; and if this be so, how can you constitute a University without the power of giving 'all' degrees: The general rule of law undoubtedly is, that where a subject matter is granted which has legal incidents belonging to it, the incidents must follow the subject granted; and this is the general rule as to corporations; and it has been decided upon that principle, that as a corporation, as an incident to its corporate character, has a right to dispose of its property, a proviso against alienation is void.

- ^ Sir William Hamilton (1853). Discussions on philosophy and literature, education and university reform. Longman, Brown, Green and Longman's. pp. 492, 497.

[p. 492] But when it has been seriously argued before the Privy Council by Sir Charles Wetherell, on behalf of the English Universities ... that the simple fact of the crown incorporating an academy under the name of university, necessarily, and in spite of reservations, concedes to that academy the right of granting all possibly degrees; nay when (as we are informed) the case itself has actually occurred, – the 'Durham University,' inadvertently, it seems, incorporated under that title, being in the course of claiming the exercise of this very privilege as a right, necessarily involved in the public recognition of the name: – in these circumstances we shall be pardoned a short excursus, in order to expose the futility of the basis on which this mighty edifice is erected. [p. 497] ... in all the Universities throughout Europe, which were not merely privileged, but created by bull and charter, every liberty conferred was conferred not as an incident through implication, but by express conversion. And this in two ways:– For a university was empowered, either by an explicit grant of certain enumerated rights, or by bestowing on it implicitly the known privileges enjoyed by other pattern Universities

- ^ Hastings Rashdall (1895). The Universities of Europe in the Middle Ages: Volume 1, Salerno, Bologna, Paris. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 11–12.

- ^ Zutshi, Patrick (2011). "When Did Cambridge Become a Studium generale?". In Pennington, Kenneth; Eichbauer, Melodie Harris (eds.). Law as profession and practice in medieval Europe : essays in honor of James A. Brundage. Farnham, Surrey, England: Ashgate. pp. 153–171. ISBN 9781409425748.

- ^ "Royal Charter". Durham University. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- ^ "Universities". Encyclopedia Britannica. Vol. 21. Black. 1860. p. 471. Archived from the original on 22 August 2024. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- ^ "History of the University". The Historical Record (1836–1912). University of London. 1912. pp. 7–24. Archived from the original on 22 August 2024. Retrieved 18 February 2019.

- ^ The Queen's University Calendar. Queens University (Ireland). 1859. p. 16. Archived from the original on 22 August 2024. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

- ^ Univ, Manchester (1882). The Victoria University Calendar. pp. 6–7. Archived from the original on 22 August 2024. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

- ^ Mordechai Feingold, ed. (2002). "Review Essay". History of Universities: Volume XVII 2001–2002. Oxford University Press. p. 192. ISBN 9780199256365. Archived from the original on 22 August 2024. Retrieved 6 February 2019.

- ^ John MacLean (1877). History of the College of New Jersey, at Princeton. Lippincott. pp. 76–79. Archived from the original on 22 August 2024. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- ^ Robert McCaughey (2003). Stand, Columbia: A History of Columbia University. Columbia University Press. p. 21. ISBN 9780231503556. Archived from the original on 22 August 2024. Retrieved 6 February 2019.

- ^ Thomas J. Frusciano (2006). "A Historical Sketch of Rutgers University: Section 1". Rutgers University Libraries. The Founding of Queen's College. Archived from the original on 13 December 2019. Retrieved 6 February 2019.

- ^ "College Charter Granted". Dartmouth College. Archived from the original on 30 August 2019. Retrieved 6 February 2019.

- ^ "Dartmouth College Case Decided By the U.S. Supreme Court". Dartmouth College. 13 October 2018. Archived from the original on 22 August 2024. Retrieved 6 February 2019.

- ^ "Trustees of Dartmouth Coll. v. Woodward, 17 U.S. 518 (1819)". Justia. Archived from the original on 18 January 2021. Retrieved 6 February 2019.

- ^ Elsie Worthington Clews Parsons (1899). Educational Legislation and Administration of the Colonial Governments. Macmillan. pp. 361–378. Archived from the original on 22 August 2024. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- ^ McSweeney, Thomas J.; Ello, Katharine; O'Brien, Elsbeth (2020). "A University in 1693: New Light on William & Mary's Claim to the Title 'Oldest University in the United States'". William and Mary Law Review Online. 61: 4. Archived from the original on 22 August 2024. Retrieved 14 July 2022.

- ^ Elsie Worthington Clews Parsons (1899). Educational Legislation and Administration of the Colonial Governments. Macmillan. p. 330. Archived from the original on 22 August 2024. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- ^ Elsie Worthington Clews Parsons (1899). Educational Legislation and Administration of the Colonial Governments. Macmillan. p. 269. Archived from the original on 22 August 2024. Retrieved 18 February 2019.

- ^ Elsie Worthington Clews Parsons (1899). Educational Legislation and Administration of the Colonial Governments. Macmillan. p. 182. Archived from the original on 22 August 2024. Retrieved 18 February 2019.

- ^ Elsie Worthington Clews Parsons (1899). Educational Legislation and Administration of the Colonial Governments. Macmillan. p. 342. Archived from the original on 22 August 2024. Retrieved 18 February 2019.

- ^ "The Harvard Charter of 1650". Harvard University. Archived from the original on 9 February 2019. Retrieved 6 February 2019.

- ^ "Governance Documents". Yale University. 5 August 2015. Retrieved 6 February 2019.

- ^ Elsie Worthington Clews Parsons (1899). Educational Legislation and Administration of the Colonial Governments. Macmillan. p. 300. Archived from the original on 22 August 2024. Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- ^ "March 1764: College Charter Granted". Brown University Timemline.

- ^ "History of Hampden-Sydney College" (PDF). Hampden-Sydney College. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 February 2019. Retrieved 6 February 2019.

- ^ Shanahan, Theresa; Nilson, Michelle; Broshko, Li Jeen (2016). The Handbook of Canadian Higher Education. McGill-Queen's Press. pp. 59–60. ISBN 9781553395058. Archived from the original on 22 August 2024. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- ^ Hind, Henry Youle (1890). The University of King's College, Windsor, Nova Scotia: 1790–1890. Church Review Company. pp. 26–30.

- ^ "History". University of King's College. Archived from the original on 23 March 2019. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- ^ "King's College Act". NSLegislature.ca. 3 December 1998. Archived from the original on 22 August 2024. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

The Royal Charter, bearing date May 12, 1802, granted by His Majesty King George III, authorizing the 'Governors, President and Fellows of King's College at Windsor in the Province of Nova Scotia' to confer degrees, is not affected by this Act, except in so far as may be necessary to give effect to this Act.

- ^ "1821 Charter". McGill University. Archived from the original on 30 July 2012. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- ^ "1852 Charter". McGill University. Archived from the original on 17 February 2019. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- ^ "King's College, New-Brunswick, January 1, 1829. Inauguration of the Chancellor". The New-Brunswick Religious and Literary Journal. 1: 4–7. 1829.

- ^ "UNB's Heraldic Tapestries". University of New Brunswick. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- ^ "The University's original charter". University of Toronto. Retrieved 15 February 2019.

- ^ "The Cobourg Years: 1829–1849". Victoria University. Archived from the original on 16 February 2019. Retrieved 15 February 2019.

- ^ Reed, Thomas Arthur (1952). A History of the University of Trinity College, Toronto, 1852–1952. University of Toronto Press. pp. 48–49.

- ^ Dorrance, Nancy (2018). "The Queen's royal charter". Queen's Alumni Review. Queen's University. Archived from the original on 22 August 2024. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- ^ "Copy of the Charter for Erecting the Seminary of Quebec into an University". Accounts and Papers of the House of Commons. 1856. Archived from the original on 22 August 2024. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- ^ "Origin and history". Laval University. Archived from the original on 18 February 2019. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- ^ "1843–1853". Bishop's University. Archived from the original on 18 February 2019. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- ^ "Brief history". University of Ottawa Archives. Archived from the original on 22 August 2024. Retrieved 17 February 2018.

- ^ Julia Horne (2017). "The final barrier? Australian women and the nineteenth-century public university". In E. Lisa Panayotidis; Paul Stortz (eds.). Women in Higher Education, 1850–1970: International Perspectives. Routledge. p. 129. ISBN 9781134458240. Archived from the original on 22 August 2024. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- ^ "Royal Charter of the University of Sydney". University of Sydney. 27 February 1858. Archived from the original on 18 June 2019. Retrieved 10 June 2019.

- ^ Kieran Crichton (2016). "Resisting the Empire? Public Music Examinations in Melbourne 1896–1914". In Paul Rodmell (ed.). Music and Institutions in Nineteenth-Century Britain. Routledge. p. 187. ISBN 9781317092476. Archived from the original on 22 August 2024. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- ^ Julia Horne (2017). "The final barrier? Australian women and the nineteenth-century public university". In E. Lisa Panayotidis; Paul Stortz (eds.). Women in Higher Education, 1850–1970: International Perspectives. Routledge. pp. 124, 128–131. ISBN 9781134458240. Archived from the original on 22 August 2024. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- ^ Marjorie R. Theobald (1996). Knowing Women: Origins of Women's Education in Nineteenth-Century Australia. Cambridge University Press. pp. 62–64. ISBN 9780521422321. Archived from the original on 22 August 2024. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- ^ V, George (1 August 2018). "Letters Patent granted to the University of Tasmania, signed 30th August 1915". eprints.utas.edu.au.

- ^ "The Development of the Company". Worshipful Company of Saddlers. Archived from the original on 20 February 2019. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

- ^ "About the Company". Worshipful Company of Merchant Taylors. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

- ^ James Paterson Ross (June 1958). "From Trade Guild to Royal College". Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 22 (6): 416–422. PMC 2413659. PMID 19310142.

- ^ "Timeline". Royal College of Physicians of London. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- ^ Henry F. Berry (30 September 1903). "The Ancient Corporation of Barber-Surgeons, or Gild of St. Mary Magdalene, Dublin". The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland. Fifth Series. 33 (3): 217–238. JSTOR 25507303.

- ^ "History of RCPI". Royal College of Physicians of Ireland. Archived from the original on 31 January 2019. Retrieved 30 January 2019.

- ^ "History of RCSI". Royal College of Surgeons of Ireland. Archived from the original on 12 January 2019. Retrieved 30 January 2019.

- ^ "Supplemental charter" (PDF). The Royal Society. 2012. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- ^ "History". Royal Irish Academy. 12 October 2015. Archived from the original on 31 January 2019. Retrieved 30 January 2019.

- ^ Simon Foxell (2018). Professionalism for the Built Environment. Routledge. pp. 114–125. ISBN 9781317479741. Archived from the original on 22 August 2024. Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- ^ "What is an Organisation formed by Royal Charter or by Special Act of Parliament?". Better Boards. 20 August 2013. Archived from the original on 22 August 2024. Retrieved 4 February 2019.

- ^ Van Vaek, Gilbert; Van Daele, Henk (1979). "Non-University Higher Technical Education in Belgium". European Journal of Education. 14 (1): 25–36. doi:10.2307/1503327. JSTOR 1503327. Archived from the original on 19 August 2020. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ Gilbert Van Vaek and Henk Van Daele Archived 23 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Belgium Royal Historical Commission Archived 13 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ [1] Archived 4 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine When is an institution considered a recognised higher education institution or a university?

- ^ R.A. Rosenfeld (17 July 2013). "The Society's 'Royal' Charter". Royal Astronomical Society of Canada. Archived from the original on 14 February 2019. Retrieved 13 February 2019.

- ^ a b Armstrong, Frederick H. (1985). Handbook of Upper Canadian Chronology: Revised Edition By Frederick H. Armstrong 1841. Dundurn. ISBN 9781770700512. Archived from the original on 22 August 2024. Retrieved 28 July 2014.

- ^ "The Canadian Encyclopedia: Literary and Historical Society of Quebec". Archived from the original on 13 December 2014. Retrieved 11 December 2014.

- ^ "History". Royal Society of Canada. 27 July 2018. Archived from the original on 2 February 2019. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- ^ "Chronological timelines". Royal Life Saving Society of Canada. Archived from the original on 15 August 2016.

- ^ a b "The Charter". Hudson's Bay Company. Archived from the original on 22 August 2024. Retrieved 14 June 2007.

- ^ "Values of the Royal Commonwealth Society". Archived 6 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine. The Royal Commonwealth Society (4 January 2007). Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- ^ "About us". Archived 5 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Royal Academy of Dance Canada. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- ^ Canada4Life; Nova Scotia Archived 4 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Canada4life.ca. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- ^ City Solicitor (June 2000), "Powers of Canadian Cities: The legal framework", Canada's Cities: Unleash our Potential, Toronto: City of Toronto, archived from the original on 17 July 2010, retrieved 23 May 2009

- ^ Canada's Cities: Unleash our Potential Archived 17 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Canadascities.ca (1 September 2001). Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- ^ Text of letters patent (royal charter) of incorporation, dated 9 September 1935. Archived 3 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 8 July 2011.

- ^ "Celebrating 145 years". University of South Africa. Archived from the original on 31 January 2019. Retrieved 30 January 2019.

- ^ "Brief History". Royal Society of South Africa. 5 July 2012. Archived from the original on 17 January 2014.

- ^ "Royal Charters". Privy Council. Archived from the original on 14 October 2011. Retrieved 20 February 2019.

- ^ "Applying for a Royal Charter". Privy Council. Retrieved 20 February 2019.

- ^ "Court of Appeal dismisses judicial review challenge to grant of Royal Charter". Withers. 30 June 2016. Archived from the original on 21 February 2019. Retrieved 20 February 2019.

- ^ a b "Chartered bodies". Privy Council. Archived from the original on 3 December 2019. Retrieved 20 February 2019.

- ^ Allan James (31 October 2006). "Trade mark application No 2226144 by the CFA Institute to register the following trade mark in class 36 and opposition to the registration under No 91541 by the Chartered Insurance Institute" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2012. Retrieved 6 February 2019.

- ^ "Annex A: Sensitive words and expressions specified in regulations that require the prior approval of the Secretary of State to use in a company or business name". Companies House. 9 August 2018. Archived from the original on 21 February 2019. Retrieved 20 February 2019.

- ^ "Certification and collective marks". Trade marks manual. Intellectual Property Office. 14 January 2019. Archived from the original on 21 February 2019. Retrieved 20 February 2019.

- ^ "Company Registration Number Formats" (DOC). HMRC.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 13 July 2018. Retrieved 30 January 2019.

- ^ Gordon R. Clapp (February 1934). "The College Charter". The Journal of Higher Education. 5 (2). Taylor and Francis: 79–87. doi:10.1080/00221546.1934.11772495. JSTOR 1975942.