Running of the bulls

| Running of the bulls | |

|---|---|

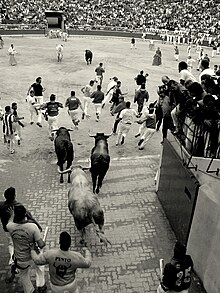

The bull run in Pamplona | |

| Dates | 7–14 July |

| Location(s) | Pamplona and other |

A running of the bulls (Spanish: encierro, from the verb encerrar, 'to corral, to enclose'; Occitan: abrivado, literally 'haste, momentum'; Catalan: bous al carrer 'bulls in the street', or correbous 'bull-runner') is an event that involves running in front of a small group of bulls, typically six[1] but sometimes ten or more, that have been let loose on sectioned-off streets in a town,[1] usually as part of a summertime festival. Particular breeds of cattle may be favored, such as the toro bravo in Spain,[1] also often used in post-run bullfighting, and Camargue cattle in Occitan France, which are not fought. Bulls (non-castrated male cattle) are typically used in such events.

The most famous bull-run is the encierro held in Pamplona during the nine-day festival of Sanfermines in honor of Saint Fermin.[2] It has become a major global tourism event, today very different from the traditional, local festival. More traditional summer bull-runs are held in other places such as towns and villages across Spain and Portugal, in some cities in Mexico,[3] and in the Occitan (Camargue) region of southern France. Bull-running was formerly also practiced in rural England, most famously at Stamford until 1837.

History

[edit]The event has its origins in the old practice of transporting bulls from the fields outside the city, where they were bred, to the bullring, where they would be fought and killed in the evening.[4] During this "run", local youths would jump among them in a display of bravado. In Pamplona and other places, the six bulls that run are also in that afternoon's bullfight.

Spanish tradition holds that bull-running began in northeastern Spain in the early 14th century. Cattle herders who wanted to transport their animals from barges or from the countryside into city centers for sale or bullfights needed an easy way to move their precious animals. While transporting cattle in order to sell them at the market, men would try to speed the process by hurrying their cattle using tactics of fear and excitement. After years of this practice, the transportation and hurrying began to turn into a competition, as young adults would attempt to race in front of the bulls and make it safely to their pens without being overtaken. This tradition is carried on each morning of the San Fermin fiesta in Pamplona, with the bulls being released from their corral at Calle de Santo Domingo to run along a barricaded route through the streets of the old quarter to the bullring at the Plaza de Toros. No longer being driven by their herders as in the past, the bulls are nowadays part of a spectacle in which a large group of runners run ahead of the bulls and attempt to beat them to the Plaza de Toros. The event has become so popular that it is a main feature of the San Fermin festival.[5] The running of the bulls was cancelled in 2020 and 2021 due to the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain, but resumed 7–14 July 2022.[6][7]

Pamplona bull run

[edit]

The Pamplona[2] encierro is the most popular in Spain and has been broadcast live by Televisión Española, the public Spanish national television service, for over 30 years.[8] It is the highest-profile event of the San Fermín festival, which is held every year from 6–14 July.[2] The first bull running is on 7 July, followed by one on each of the following mornings of the festival, beginning every day at 8 am. The rules require participants to be at least 18 years old, run in the same direction as the bulls, not incite the bulls, and not be under the influence of alcohol.[9][10]

Fence

[edit]In Pamplona, a set of wooden fences is erected to direct the bulls along the route and to block off side streets. A double wooden fence is used in those areas where there is enough space, while in other parts the buildings of the street act as barriers. The gaps in the barricades are wide enough for a human to slip through but narrow enough to block a bull. The fence is composed of approximately three thousand separate pieces of wood. Some parts of the fence remain in place for the duration of the fiesta, while others are placed and removed each morning.[11] Spectators can only stand behind the second fence, whereas the space between the two fences is reserved for security and medical personnel and also for participants who need cover during the event.[10]

Preliminaries

[edit]

The encierro begins with runners singing a benediction. It is sung three times, each time being sung both in Spanish and Basque. The benediction is a prayer given at a statue of Saint Fermin, patron of the festival and the city, to ask the saint's protection and can be translated into English as "We ask Saint Fermin, as our Patron, to guide us through the encierro and give us his blessing". The singers finish by shouting "¡Viva San Fermín! and Gora San Fermin! ('Long live Saint Fermin', in Spanish and Basque, respectively).[9] Most runners dress in the traditional clothing of the festival which consists of a white shirt and trousers with a red waistband (faja) and neckerchief (pañuelo). Also some of them hold the day's newspaper rolled to draw the bulls' attention from them if necessary.[9]

The running

[edit]

A first rocket is set off at 8 a.m. to alert the runners that the corral gate is open. A second rocket signals that all six bulls have been released. The third and fourth rockets are signals that all of the herd has entered the bullring and its corral respectively, marking the end of the event.[9] The average duration between the first rocket and the end of the encierro is two minutes, 30 seconds.[9]

The encierro is usually composed of the six bulls to be fought in the afternoon, six steers that run in herd with the bulls, and three more steers that follow the herd to encourage any reluctant bulls to continue along the route. The function of the steers, who run the route daily, is to guide the bulls to the bullring.[9] The average speed of the herd is 24 km/h (15 mph).[9]

The length of the run is 875 meters (957 yards). It goes through four streets of the old part of the city (Santo Domingo, Ayuntamiento, Mercaderes and Estafeta) via the Town Hall Square and the short section "Telefónica" (named for the location of the old telephone office at end of Calle Estafeta) just before entering into the bullring through its callejón (tunnel).[2] The fastest part of the route is up Santo Domingo and across the Town Hall Square, but the bulls often became separated at the entrance to Estafeta Street as they slow down. One or more would slip going into the turn at Estafeta ("la curva"), resulting in the installation of anti-slip surfacing, and now most of the bulls negotiate the turn onto Estafeta and are often ahead of the steers. This has resulted in a quicker run. Runners are not permitted in the first 50 meters of the encierro, which is an uphill grade where the bulls are much faster.[citation needed]

Injuries, fatalities, and medical attention

[edit]

Every year, between 50 and 100 people are injured during the run[9] Not all of the injuries require taking the patients to hospital: in 2013, 50 people were taken by ambulance to Pamplona's hospital, with this number nearly doubling that of 2012.[12]

Goring is much less common but potentially life threatening. In 2013, for example, six participants were gored along the festival, in 2012, only four runners were injured by the horns of the bulls with exactly the same number of gored people in 2011, nine in 2010 and 10 in 2009; with one of these last killed.[12][13] As most of the runners are male, only 5 women have been gored since 1974. Before that date, running was prohibited for women.[14]

Another major risk is runners falling and piling up (a "montón", meaning "heap") at the entrance of the bullring, which acts as a funnel as it is much narrower than the previous street, resulting in a crowd crush. In such cases, injuries come both from asphyxia and contusions to those in the pile and from goring if the bulls crush into the pile. This kind of blocking of the entrance has occurred at least ten times in the history of the run, the last occurring in 2013 and the first dating back to 1878. A runner died of suffocation in one such pile up in 1977.[15]

Overall, since record-keeping began in 1910, 15 people have been killed in the bull running of Pamplona, most of them due to being gored.[9] To minimize the impact of injuries every day 200 people collaborate in the medical attention. They are deployed in 16 sanitary posts (every 50 metres on average), each one with at least a physician and a nurse among their personnel. Most of these 200 people are volunteers, mainly from the Red Cross. In addition to the medical posts, there are around 20 ambulances. This organization makes it possible to have a gored person stabilized and taken to a hospital in less than 10 minutes.[16]

| Year | Name | Age | Origin | Location | Cause of death |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1924 | Esteban Domeño | 22 | Navarre, Spain | Telefónica | Goring[17] |

| 1927 | Santiago Zufía | 34 | Navarre, Spain | Bullring | Goring[17] |

| 1935 | Gonzalo Bustinduy | 29 | San Luis Potosí, Mexico | Bullring | Goring[17] |

| 1947 | Casimiro Heredia | 37 | Navarre, Spain | Estafeta | Goring[17] |

| 1947 | Julián Zabalza | 23 | Navarre, Spain | Bullring | Goring[17] |

| 1961 | Vicente Urrizola | 32 | Navarre, Spain | Santo Domingo | Goring[17] |

| 1969 | Hilario Pardo | 45 | Navarre, Spain | Santo Domingo | Goring[17] |

| 1974 | Juan Ignacio Eraso | 18 | Navarre, Spain | Telefónica | Goring[17] |

| 1975 | Gregorio Gorriz | 41 | Navarre, Spain | Bullring | Goring[17] |

| 1977 | José Joaquín Esparza | 17 | Navarre, Spain | Bullring | Suffocated in a pile-up.[9] |

| 1980 | José Antonio Sánchez | 26 | Navarre, Spain | Town Hall Square | Goring[17] |

| 1980 | Vicente Risco | 29 | Badajoz, Spain | Bullring | Goring[17] |

| 1995 | Matthew Peter Tassio | 22 | Glen Ellyn, Illinois, USA | Town Hall Square | Goring[18] |

| 2003 | Fermín Etxeberria | 62 | Navarre, Spain | Mercaderes | Goring[19] |

| 2009 | Daniel Jimeno Romero | 27 | Alcalá de Henares, Spain | Telefónica | Goring[20][21] |

Dress code

[edit]

Though there is no formal dress code, the very common and traditional attire is white trousers, a white shirt with a red cummerbund around the waist, and a red neckerchief around the neck.[22] Some have large logos on their shirts; in the Internet age this is thought to be a way to highlight someone in a photo. This dress is to honor San Fermin, the center of the celebration, because of his martyr's death; the white outfits represent the purity and holiness of a saint, and the red kerchiefs (pañuelos), represent his death by decapitation. A common alternate color to red is blue.

Media

[edit]

The encierro of Pamplona has been depicted many times in literature, television or advertising, but became known worldwide partly because of the descriptions of Ernest Hemingway in books The Sun Also Rises and Death in the Afternoon.[23]

The cinema pioneer Louis Lumière filmed the run in 1899.[24]

The event is the basis for a chapter in James Michener's 1971 novel The Drifters.

The run is depicted in the 1991 Billy Crystal film City Slickers, where the character "Mitch" (Crystal) is gored (non-fatally) from behind by a bull during a vacation with the other main characters. Filmmakers traveled to Spain to shoot the actual running of the bulls with second unit director, Heston Fraser. City Slickers director, Ron Underwood, recreated the Pamplona location on the Universal Studios backlot to stage the running of the bulls with the actors.

The run appears in the 2011 Bollywood movie Zindagi Na Milegi Dobara, directed by Zoya Akhtar, as the final dare in the bucket list of the three bachelors who have to overcome their ultimate fear; death. At first, the trio run part of the route. They stop at the square, but then recover their nerve, and continue to the end. The completion of the run depicts their freedom as they learn that surviving a mortal danger can bring joy.

Running with Bulls, a 2012 documentary of the festival filmed by Construct Creatives and presented by Jason Farrel, depicts the pros and cons of the controversial tradition.[25]

From 2014 until 2016, the Esquire Network broadcast the running of the bulls live in the United States,[26] with both live commentary and then a recorded 'round up' later in the day by NBCSN commentators the Men in Blazers, including interviews with noted participants such as Madrid-born runner David Ubeda,[27] former US Army soldier turned filmmaker Dennis Clancey,[28] and former British bullfighter and author Alexander Fiske-Harrison.[29]

In 2014, a guidebook authored by Alexander Fiske-Harrison, Ernest Hemingway's grandson John, Orson Welles' daughter Beatrice, and with a foreword by the Mayor of Pamplona, caused headlines around the world when one of the contributors, Bill Hillmann, was gored by a bull soon after its publication. It was republished in 2017 under the title The Bulls Of Pamplona with a replacement chapter by Dennis Clancey.[30]

The award-winning 2015 feature documentary Chasing Red directed by Dennis Clancey, follows four runners during the 2012 fiesta in Pamplona, including Bill Hillmann and David Ubeda.[31][32][33]

Other examples

[edit]

Although the most famous running of the bulls is that of San Fermín,[2] they are held in towns and villages across Spain, Portugal, and in some cities in southern France during the summer. Examples are the bull run of San Sebastián de los Reyes, near Madrid, at the end of August, which is the most popular of Spain after Pamplona; the bull run of Cuéllar, considered as the oldest of Spain since there are documents of its existence dating back to 1215; the Sanjuanes of Coria (Cáceres, Extremadura) since XV century is original and dangerous; the Highland Capeias of the Raia in Sabugal, Portugal, with horses leading the herd crossing old border passes out of Spain and using the medieval 'Forcåo'; and the bull run of Navalcarnero held at night.

Other encierros have also caused fatalities.[34]

Correbous or bous al carrer

[edit]

Bous al carrer, correbou or correbous (meaning in Catalan, 'bulls in the street', 'street-bulls' or 'bull-running') is a typical festivity in many villages in the Valencian region, Terres de l'Ebre, Catalonia, and Fornalutx, Mallorca. Another similar tradition is soltes de vaques, where cows are used instead of bulls. Even though they can take place all along the year, they are most usual during local festivals (normally in August). Compared to encierros, animals are not directed to any bullring.

These festivities are normally organized by the youngsters of the village, as a way for showing their courage and ability with the bull. Some sources consider this tradition a masculine initiation rite to adulthood.[35]

Occitan area of France

[edit]

Numerous bull-running events happen in France in the region around Sommières, in accordance with the Camargues tradition, in which no bulls are intentionally injured or killed. For instance, in Calvisson, the annual event takes place around 20 July over a period of five days. There are four events: the abrivado, in which at least ten bulls are run together through the street guided by a group of twelve gardians mounted on white Camargue horses; the encierro, in which one bull is released outside the foyer and finds his own way back to the pen; the bandido, in which one bull is run, accompanied through the streets; and the bandido de nuit, which is the same thing but after dark. Boys and men run with the bulls and try and separate them from the horses, stop them, and physically turn them away from the horses. [36]

Stamford bull run

[edit]The English town of Stamford, Lincolnshire was host to the Stamford bull run for almost 700 years until it was abandoned in 1837.[37] According to local tradition, the custom dated from the time of King John when William de Warenne, 5th Earl of Surrey, saw two bulls fighting in the meadow beneath. Some butchers came to part the combatants and one of the bulls ran into the town, causing a great uproar. The earl mounted his horse and rode after the animal, and enjoyed the sport so much that he gave the meadow in which the fight began to the butchers of Stamford, on condition that they should provide a bull to be run in the town every 13 November, for ever after. As of 2013 the bull run had been revived as a ceremonial, festival-style community event.

Mock bull runs

[edit]A variation is the nightly "fire bull" where balls of flammable material are placed on the horns. In modern times, the bull is often replaced by a runner carrying a frame on which fireworks are placed, and dodgers, usually children, run to avoid the sparks.

The Encierro de la Villavesa ("running of the town bus") started in Pamplona on 15 July 1984 when, after the end of the festival, youths would run before the earliest urban bus entering the traditional encierro course. Starting in 1990, the Pamplona City Transport detoured the early bus to reduce the risk. Currently,[when?] the youths run before a cyclist in a yellow jersey as an homage to the Navarrese cycling champion Miguel Induráin.[38]

In 2008, Red Bull Racing driver David Coulthard and Scuderia Toro Rosso driver Sébastien Bourdais performed a version of a 'bull running' event in Pamplona, Spain, with the Formula One cars chasing 500 runners through the actual Pamplona route.[39]

The Big Easy Rollergirls roller derby team has performed an annual mock bull run in New Orleans, Louisiana since 2007. The team, dressed as bulls, skates after runners through the French Quarter. In 2012, there were 14,000 runners and over 400 "bulls" from all over the country, with huge before- and after-parties.[40][41][42]

In Ballyjamesduff, Ireland, an annual event called the Pig Run is held, functioning as a mini-encierro but with small pigs in place of bulls.

In Dewey Beach, Delaware, a bar named The Starboard sponsors an annual Running of the Bull [sic], in which hundreds of red- and white-clad beachgoers are chased down the shore by a single "bull" (two people in a pantomime horse-style costume).[43]

In Rangiora, New Zealand, an annual Running of the Sheep is held, in which 1000–2000 sheep are released down the main street of the small farming town.

The Running of the Bulls UK is a pub crawl event that takes place on London's Hampstead Heath and uses fast human runners in place of bulls.

In 2014, Pamplona inaugurated a series of running events in June, the San Fermín Marathon, of a full marathon (42.195 km), half-marathon (21.097 km), or 10 km road race that concludes with the final 900m of each race using the encierro route, runners crossing the finish line inside the bullring.[44]

Since 2008 in Anchorage, Alaska during the Fur Rendezvous Festival, the Running of the Reindeer has participants run down a four-block downtown street with a group of reindeer released behind them.

Opposition

[edit]Many opponents state that bulls are mentally stressed by the harassment and voicing of both participants and spectators, and some of animals may also die because of the stress, especially if they are roped or bring flares in their horns (bou embolat version).[45] Despite all this, the festivities seem to have wide popular support in their villages.[46]

The city of San Miguel de Allende, Mexico, cancelled its Sanmiguelada running of the bulls after 2006, citing public disorder associated with the event.[47] After the event was cancelled in San Miguel, the city of Salvatierra, also in the state of Guanajuato, picked up the event. It is now called La Marquesada and the three-day event is held during the last weekend of the month of September or first weekend of October.

As of 2002, a Running of the Nudes occurs two days before the running of the bulls. The event is supported by animal welfare groups, including PETA, who object to the running of the bulls, claiming that it is cruel and glorifies bullfighting, which the groups oppose.

Further reading

[edit]- Fiske-Harrison, Alexander, ed. (2018). The Bulls Of Pamplona (1 ed.). Mephisto Press. ISBN 978-1986500272.

- Hillmann, Bill (2015). Mozos: A Decade Running with the Bulls of Spain. Chicago, Illinois: Curbside Splendor Publishing. ISBN 978-1-9404-3053-9. Archived from the original on 22 June 2021. Retrieved 27 November 2016.

- Hillmann, Bill (2021). The Pueblos: My Quest to Run 101 Bull Runs in the Small Towns of Spain. Chicago, Illinois: Tortoise Books. ISBN 978-1-9489-5417-4.

- Etxanobe, Ander (2021). The Basque: An American's Journey to Embrace His Roots. Txapela Publishing. ISBN 978-1736948101.

See also

[edit]- Bou embolat or toro embolado – variant in which bulls have flares or fireworks attached to their horns

- Bull-baiting - form of blood sport

- Bullfighting

- Bull-leaping (ancient)

- Course landaise (modern France)

- Recortes (modern Spain)

- Bull running – a similar, defunct tradition in England

- Jallikattu – a similar tradition in Tamil Nadu, India

- Sokamuturra, similar to the encierro, spread over different parts of the Basque Country

References

[edit]Some links may contain graphic content where marked.

- ^ a b c Fiske-Harrison, Alexander (editor) The Bulls Of Pamplona, Mephisto Press, 2018

- ^ a b c d e "Sanfermin guide: Running of the bulls". Kukuxumusu. 2007. Archived from the original on 5 May 2008. Retrieved 21 July 2008.

- ^ "Bull-run hits liquor-fueled town", 2 February 2009. "The tradition, enacted in a handful of Mexican towns, traces its roots back to the centuries-old Pamplona bull-run in Mexico's former colonial power." Retrieved 4 March 2009.

- ^ According to the Mayor of Pamplona in his foreword to the book Fiesta: How to Survive the Bulls of Pamplona

- ^ Ravenscroft, Neil; Matteucci, Xavier (1 January 2003). "The Festival as Carnivalesque: Social Governance and Control at Pamplona's San Fermin Fiesta" (PDF). Tourism Culture & Communication. 4 (1): 5. doi:10.3727/109830403108750777.

- ^ "Running of the Bulls 2021 Officially Cancelled". www.runningofthebulls.com. 26 April 2021. Retrieved 6 July 2021.

- ^ "Running of the Bulls 2022 Dates". www.runningofthebulls.com. 5 April 2021. Retrieved 6 July 2021.

- ^ "27 años de Sanfermines en TVE". RTVE. 2008. Retrieved 21 July 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "The Bull Run". Pamplona.net. Ayuntamiento de Pamplona (Council of Pamplona). 2008. Archived from the original on 29 May 2008. Retrieved 21 July 2008.

- ^ a b "Sección quinta". Bando San Fermin 2014. Ayuntamiento de Pamplona. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- ^ "Encierro bullrun San Fermin festival Sanfermines tourist information on Navarre". Government of Navarre. Retrieved 8 March 2010.

- ^ a b Alonso, Gorka (15 July 2013). "Los encierros se saldan con 50 heridos trasladados y 6 corneados". Noticias de Navarra (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 16 July 2013. Retrieved 15 July 2013.

- ^ "Los encierros de 2012 dejan cuatro heridos por asta, los mismos que en 2011". Diario de Noticias (in Spanish). 14 July 2012. Archived from the original on 19 July 2012. Retrieved 13 July 2013.

- ^ "Quinta mujer corneada en los encierros de San Fermín" (in Spanish). Diario de Navarra. EFE. 14 July 2013. Retrieved 15 July 2013.

- ^ Doria, Javier (13 July 2013). "Montón en el encierro de Sanfermines, un peligro con historia". El País (in Spanish). Retrieved 14 July 2013.

- ^ "Especialistas destacan que el dispositivo sanitario de los encierros "no se puede mejorar" porque es "espectacular"". Diario de Navarra (in Spanish). 18 June 2009. Archived from the original on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 16 July 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "La muerte de hoy es la número quince en la historia del encierro". Terra Noticias (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 12 July 2012. Retrieved 6 July 2012.

- ^ "The last person killed at Pamplona". BBC News. British Broadcasting Corporation. 14 July 2005. Retrieved 10 July 2009.

...Matthew Tassio...22 years old and came from Chicago...The...bull...hit him in the abdomen, severed a main artery, sliced through his kidney and punctured his liver

- ^ "Muere el pamplonés Fermín Etxeberria, de 63 años, herido en el encierro del 8 de julio". DiarioDeNavarra.es (in Spanish). 25 September 2003. Archived from the original on 3 August 2009. Retrieved 10 July 2009.

- ^ "Bull gores man to death in Spain". BBC News. 10 July 2009. Retrieved 10 July 2009.

The 27-year-old was gored in the neck on Friday, during the fourth bull run of the week-long San Fermin festival. Daniel Jimeno Romero, from Madrid, had emergency surgery in hospital but died of his injuries. Earlier reports had described the dead man as British....a veteran Spanish bull-runner died after a fall in 2003

- ^ "One dead in the running of the bull's in Pamplona". EncierroSanFermin.com. 10 July 2009. Archived from the original on 14 July 2009. Retrieved 10 July 2009.

A runner died in today's running of the bulls in the northern spanish city of Pamplona, the bull running held during the famous San Fermin festivities. The man died after being gored in the neck and lung by a bull of the Jandilla ranch, named "Capuchino".The runner, Daniel Jimeno Romero from Alcalá de Henares (Madrid) was at the end of the street run

- ^ Tan, Rebecca (6 July 2018). "As bull run revelry kicks off in Pamplona, hundreds wear black to mourn victims of sexual assault". Washington Post.

- ^ "Hemingway in Spain. A definitive guide to Ernest Hemingway's Spain". 15 March 2022.

- ^ Encierro de toros in the Spanish-language Auñamendi Encyclopedia.

- ^ Running with Bulls at IMDb

- ^ 'Running Of The Bulls', Esquire TV

- ^ Vadillo, Jose Luis. 'Así son los corredores de elite en San Fermín', El Mundo. 6 July 2015

- ^ Editorial Staff. "Pamplona, bull running, bull gorings, Esquire TV and poetry from New York"[usurped], The Pamplona Post. 10 July 2015

- ^ "Running of the Bulls 2015: A Democratic Sport" Archived 17 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Esquire TV

- ^ Fiske-Harrison, Alexander, "The Bulls Of Pamplona

- ^ "The People Trying to Use Technology to Save Nature". 15 May 2021.

- ^ "Chasing Red (2020) - IMDb". IMDb.

- ^ "This Iraq war veteran has been running with the bulls since 2007". 5 February 2020.

- ^ Mari Carmen López del Burgo, aged 48, from Madrid, Spain. "Muere una mujer embestida por un toro en los encierros de Arganda del Rey". ElPais.com (in Spanish). 9 September 2010. Retrieved 9 September 2010.

- ^ Touristic leaflet. Festes de la Costa Blanca, Diputació Provincial d'Alacant, 2006, Alacant.

- ^ "Taurine traditions". OT-Sommieres.com. Office de Tourisme du Pays de Sommières. Archived from the original on 22 August 2017. Retrieved 22 August 2017.

- ^ Chambers Book of Days (1864). W. & R. Chambers Ltd. 1832. 13 November entry

- ^ Rolán, Saioa (8 June 2022). "Encierro de la Villavesa: qué es, cuándo se celebra y curiosidades". diariodenavarra.es (in European Spanish). Retrieved 7 July 2022.

- ^ "Red Bull to visit Pamplona for Bull running". GPUpdate.net. 11 June 2008. Retrieved 30 January 2011.

- ^ Marszalek, Keith I. (24 June 2007). "Big Easy Rollergirls to reinact [sic] famed bull run". Blog.NOLA.com. Archived from the original on 25 July 2011. Retrieved 2 July 2011.

- ^ "San Fermín in Nueva Orleans, The Running of the Roller Girls". Laughing Squid. 20 July 2008. Retrieved 2 July 2011.

- ^ Coviello, Will. "Running of the Bulls 2012". Gambit Weekly. Archived from the original on 17 July 2012. Retrieved 18 July 2012.

- ^

- Cormier, Ryan (23 June 2017). "Turning 21, party time for Running of the Bull". The News Journal. Wilmington, DE.

- Driscoll, Ellen (5 July 2019). "Running of the Bull takes over Dewey Beach". Cape Gazette. Lewes, DE.

- Gonzalez, Lucas (26 June 2019). "Dewey Beach's Running of the Bull: The zany hit of summer". The Daily Times. Salisbury, MD.

- ^ "Home2018 - EDP San Fermín Marathon". SanFerminMarathon.com.

- ^ Article sobre la crueltat dels bous al carrer. Archived 12 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine (in Catalan)

- ^ Article sobre la popularitat dels bous al carrer a les terres de l'Ebre. (in Catalan)

- ^ "No More Bull (Running, That Is) in San Miguel de Allende," Archived 7 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine Austin American-Statesman, 24 May 2007. Retrieved 4 March 2009

External links

[edit]- Definitive Guide to Running with Bulls, Pamplona's Running of the Bulls, How To

- A blog about Pamplona's annual bull-running festival[usurped]

- How to attend or view the Pamplona festival

- Student Travel and Party at Running of the Bulls

- Google Maps Route Map

- Running of the Bulls Tours Archived 30 June 2017 at the Wayback Machine