Music of Seattle

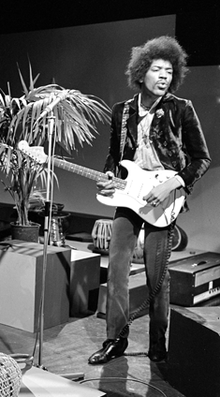

Seattle is the largest city in the U.S. state of Washington and has long played a major role in WA state's musical culture as well as an influential international role on music. The original birthplace of guitarist Jimi Hendrix, the Seattle music scene has popularized particular genres of alternative rock such as grunge, and was also the origin and home of major bands like Alice in Chains, Soundgarden, Pearl Jam, Screaming Trees, Mudhoney, Foo Fighters, and Nirvana.[1]

Seattle is home to the globally influential public radio station KEXP-FM. The city and surrounding metropolitan area also remains home to several influential artists, bands, labels, and venues, and is home to several symphony orchestras; and world-class choral, ballet and opera companies, as well as amateur orchestras and big-band era ensembles.

History

[edit]1800s–1945: Founding

[edit]Seattle's music history begins in the mid-19th century, when the first European settlers arrived. In 1909, amidst the boosterism engendered by the city's first world's fair, the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition, the Seattle City Council adopted "Seattle, the Peerless City" (words by Arthur O. Dillon; music by Glenn W. Ashley) as Seattle's official song.[2]

By the early 20th century, Seattle had an upper-class society that established an urban culture, which included music;[citation needed] the city's high culture was, however, shadowed by that of San Francisco, which was then the major cultural center of the West Coast. Seattle also became an important stop for vaudeville tours, put on by large chains like Pantages and Considine; the city also produced a major attraction in the exotic dancer Gypsy Rose Lee. The Whangdoodle Entertainers was one of Seattle's first jazz bands. By the 1920s, Seattle had also come to support a politically radical American folk scene, inspired in part by several lengthy stays in the region by folk singer Woody Guthrie; Seattle's folk performers included Ivar Haglund, who later founded a chain of successful seafood restaurants. The Seattle jazz scene included Jelly Roll Morton for several years in the early part of the century, as well as Vic Meyers, a local performer and nightclub owner who became Lieutenant Governor in 1932.[3] E. Russell "Noodles" Smith, founder of the Dumas Club and the Entertainers Club, was another important name in the Seattle Jazz scene of the day.[4][page needed]

Early musical establishments of the "classical" vein included the art school founded by Nellie Cornish, which saw residencies from both John Cage and Martha Graham, and the Seattle Symphony, which gave its first concert in 1903. From 1941 to 1943, Thomas Beecham was on a world-wide tour and served as the conductor of the Seattle Symphony as well as the New York Metropolitan Opera (and apparently an occasional gig with the Vancouver Symphony). Thomas Beecham either described Seattle as a "cultural dustbin" or warned that it could become one.[5] The passage of time would prove different.

1945–1975: Postwar era and popular music expansion

[edit]World War II brought a "flourishing" vice scene, where "booze, gambling and prostitution" were unchecked by "paid-off cops". The Showbox Ballroom was a center for these activities; it was open twenty-four hours a day, geared towards active members of the military, featuring popular performers like the racy Gypsy Rose Lee. In addition to the Showbox, Washington Hall, Parker's, Odd Fellows Temple and Trianon were also major big band ballrooms, all of which eventually became major rock music venues.

Police officers also tolerated an after-hours jazz scene, based in Chinatown, Seattle and including most famously the Black and Tan Club. This period produced a few local performers of note, including Ray Charles, who recorded his first single and made his debut television appearances and radio broadcasts in Seattle, and Bumps Blackwell. Blackwell was a bandleader whose band included the instrumentalist Quincy Jones. Harry Everett Smith was a college student in the 1940s when he found a number of recordings of folk music about to be recycled at a Salvation Army depot. He rescued the recordings, which became hot commodities when released by Folkways on the landmark Anthology of American Folk Music.[6]

Music patriarch Frank D. Waldron was an early member of the just formed black musicians' union, AFM Local 458. African Americans challenged and changed the Jazz culture within Seattle with great force.[7]

Changes to local regulations in 1949 prompted a shift from "private clubs" to "restaurant-lounge combinations" which "didn't support much in the line of creative nightlife"[citation needed] and even helped to drive out the city's jazz nightclub scene. Boeing emerged in the 1940s and 1950s as one of the city's largest employers, and, according to local music historian Clark Humphrey, helped give the city a reputation as "quiet, orderly (and) dull"; in the mid-1950s, Seattle Post-Intelligencer reporter Emmett Watson was asked to begin a column on Seattle's happenings, but he responded that there was nothing worth writing about.

The early 1960s saw Seattle become home to a local dance scene built around venues like the Trianon and Parker's. The city also became the major center for recorded popular music in the Pacific Northwest, and had the first American pop hit from the region with the Fleetwoods "Come Softly to Me" in 1959.

That same year, the DJ Pat O'Day began working for KJR, and then mounted a series of teen dances featuring bands like the Fabulous Wailers, later to become famous as the Wailers with hits like "Tall Cool One." The Wailers first album came out on Golden Crest Records; subsequent releases came out on Etiquette, the first record label owned by the band that recorded for it. The Wailers only had one more national hit, "Mau Mau", but released a long series of regionally popular recordings. Though the Wailers were popular in the Seattle area, they were actually from Tacoma, as were several other regional bands including the Swaggerz.[8]

O'Day worked with a number of local bands, several of whom had regional hits like the Frantics' "Werewolf" and "Straight Flush". The Frantics, the Wailers, and most other local rock bands in the Pacific Northwest were basically instrumental combos, with limited vocals or none at all. the Ventures and the Viceroys were both largely instrumental, with the former gaining national acclaim as a surf band.

Though most of the regionally important bands in the 1960s were dominated by white men, Seattle also produced a few female country rock performers, most notably Merrilee Rush and Bonnie Guitar. The city's black music scene include Ron Holden, a soul singer whose "Love You So" was a Top Ten hit, vocal group the Gallahads and R&B instrumentalist Dave Lewis, who had several hits like "David's Mood" and "Little Green Thing".

Seattle's most famous musical export is Jimi Hendrix, who began performing in the city but did not gain a national reputation until moving to England.[9] Though Hendrix had to move to England to start his recording career, the reverse also became true for the musicologist Ian Whitcomb, who performed in the city in the 1960s. He recorded "This Sporting Life" with Gerry Rosalie of the Sonics, and the song became a major hit, and an early anthem for the gay community.

Sax/conga drum vocalist Gerald Brashear and Wanda Brown were fixtures in the Seattle jazz scene from the 1930s to the 80s.[4][page needed]

1975–1985: Counterculture

[edit]Music author Steven Blush described the Seattle music scene of the late 1970s and early 1980s as crucial in its "vibe and ethic" which inspired grunge music. The earliest local alternative music scene was based around a gay glam theater group called Ze Whiz Kids, one of whose members, Tomata du Plenty, became a fixture in New York before returning in 1976 as part of the Tupperwares with long-time boyfriend Gorilla Rose; Blush described this as the first punk rock in the area.[10] The first punk concert in Seattle was the Tupperwares backed by the Telepaths at the grand premiere of Pink Flamingos at the Moore Theater on New Years night, 1976. Tomata and Gorilla left for Los Angeles in 1977, but a new wave of local bands emerged in their wake, congregating at a local venue called The Bird. These bands included the Enemy, the Lewd, the Mentors, Chinas Comidas, the Telepaths, the Beakers, Red Dress, X-15 and the Meyce.

Following The Bird, local punk centered around an old theatre called The Showbox, where touring bands from Los Angeles, New York, London and elsewhere played. Other, smaller venues included The Gorilla Room and Wrex, which later became Vogue. Hardcore punk, a loud, intense and angry form of punk, first came to Seattle in the band Solger,[citation needed] which formed in 1980. They were followed by the Fartz, who included Paul Solger of Solger, and became well known in hardcore scenes across the West Coast, and touring with Black Flag and the Dead Kennedys. The Fartz dissolved in 1982, just as their EP World Full of Hate was released by Alternative Tentacles. Other local bands included the Fags, the Refuzors, the Rejectors, and the DT's; both the Refuzors and the DT's were led by Mike Refuzor née Michael Lambert. The Fastbacks were affiliated with the scene, but were not considered either hardcore or punk. Also of note from this time frame is the national emergence of progressive heavy metal artists Queensrÿche (from Bellevue, a suburb of Seattle).

Fifteen bands of that era, including the Blackouts, the Pudz, the Fastbacks and the Fartz contributed songs to the first edition of the "Seattle Syndrome" compilation, released in late 1981 on Engram Records and regarded by music historian Stephen Tow as "a critical yardstick in the history of underground Seattle music".[11]

Heart, fronted by sisters Ann and Nancy Wilson of Bellevue, got their start in the Seattle area in local bands while still in their teens. Their fame was achieved while residing in Vancouver B.C. Canada, with their 1975 debut album Dreamboat Annie. Ann's boyfriend Mike Fisher, brother of original Heart guitarist Roger Fisher, was evading the Vietnam draft in Canada. Ann met and followed him to Vancouver. Mike was the band's original manager. Upon amnesty granted by President Carter, on January 21, 1977, Heart returned to the United States and signed with Capitol Records. Heart was inducted into the Rock and Rock Hall of Fame in April 2013.

1985–1997: Grunge music

[edit]Prior to the mid-1980s, the local hardcore and metal scenes were often violently confrontational with each other. The opening of the Gorilla Gardens venue changed that by offering two separate shows at the same time; as a result, both hardcore and metal were frequently played on the same nights. The softening of relations between the two groups helped inspire the look and sound of grunge,[citation needed] a term allegedly coined by Mark Arm of the brief joke band Mr. Epp and the Calculations who gained some local notoriety.

Two local bands later become well-known icons of the era: The U-Men and Green River, the latter of which has been cited as the true beginning of grunge.[12] Local music author Clark Humphrey has attributed the rise of grunge, in large part, to the scene's "supposed authenticity", to its status as a "folk phenomenon, a community of ideas and styles that came up from the street" rather than "something a couple of packagers in a penthouse office" dreamed of, as well as Seattle's isolation from the mainstream record industry.[13][14] Rebee Garofalo attributes to the unlikely rise of Seattle's alternative rock to the legacy of local rock left behind by the Ventures and Jimi Hendrix.[15]

The grunge scene revolved around Sub Pop, a record label founded by Bruce Pavitt and Jonathan Poneman in 1986. Sub Pop was founded by Bruce Pavitt, who began with a local radio show and began releasing tapes of local bands.[16] Radio stations like KJET, KGRG and KCMU and local music press like Backlash and Seattle Rocket and City Heat Magazine also played a vital role. Grunge's entrance into the mainstream is usually traced to the release of Nirvana's Nevermind in 1991, though others point to the signing of Soundgarden to A&M Records in 1988 and their Grammy-nominated Ultramega OK. Though Soundgarden failed to bring in large national audiences at the time, record executives saw enough promise to send scouts out to the major bands, many of whom signed to large labels.

The 1991 release of Nevermind catapulted the local scene into international fame. Nirvana, Pearl Jam, Alice in Chains, Soundgarden, and other grunge bands became bestselling national groups; many of their earlier fans greeted this development with cries of selling out, and the bands themselves struggled with the irony of alternative rock bands entering mainstream pop culture. Seattle grunge as national fare declined within a few years, however, beginning with the suicide of Nirvana frontman Kurt Cobain in 1994[17] and ending with Soundgarden's breakup in 1997.[18]

During the 1990s other forms of music also existed, including bands such as the Posies, Kill Switch...Klick, Faith & Disease, Sky Cries Mary, and Harvey Danger.

1997–present: Expansion and global Influence

[edit]In 2001, the University of Washington affiliated KCMU station changed their call sign to KEXP-FM. The station gained major technological updates with funding from Paul Allen, as the station's engineers developed the radio industry's first real-time playlist, and launched the industry's first online streaming archive by 2002. While the station unveiled its live video-streaming service via YouTube in 2014, KEXP quickly attracted over 500 million viewers worldwide by 2016[19] and more than 1 million subscribers by 2019, becoming a global influence for established artists while also continuing to champion emerging Seattle music.[20] In 2024, the station surpassed 3 million subscribers on YouTube and announced the launching of a broadcast station in San Francisco as well.[21][22]

Even though the prolific grunge-era had faded by the late 1990s, Seattle music has continued to maintain a strong influence in the independent music world via the expansion of KEXP, as well as through the sustained work of Seattle labels like Sub Pop, Suicide Squeeze Records (est. 1996) and Barsuk Records (est. 1998), who signed and promoted influential Seattle and Northwest-regional bands such as Modest Mouse, Sleater-Kinney, Sunny Day Real Estate, Death Cab for Cutie, Band of Horses, Fleet Foxes, The Head and the Heart, Shabazz Palaces, David Bazan, Minus the Bear, This Will Destroy You and Kinski (band). Seattle has also become an established home of influential hip hop music, with Sir Mix-a-Lot and Ishmael Butler of Shabazz Palaces being followed by the likes of the Blue Scholars, Macklemore, Common Market, Oldominion, Jake One, Lil Mosey, THEESatisfaction, DoNormaal, Gifted Gab, Travis Thompson and Clipping (band).[23]

While the grunge-era venue The Crocodile Cafe closed in 2007 (i.e. where Nirvana played some of their earliest live shows), the venue reopened again in March 2009 and later relocated into a larger space within Seattle's Belltown Neighborhood in 2021.[24][25] Numerous cherished venues such as the Vera Project,[26] Neumos, Sunset Tavern and the Tractor Tavern have all continued to adapt and showcase live performances of both nationally touring acts and local bands.[27] The Tractor tavern celebrated 30 years of live music from Seattle's Ballard neighborhood in 2024, and the beloved Conor Byrne Pub also re-opening under a cooperative model in the same year.[28][29]

Despite the adverse impacts on independent artists caused by rising cost of living in Seattle over this time,[30][31] Seattle's robust DIY and feminist punk scene flourished through the 2000's and 2010's, led by bands such as Tacocat, Childbirth, and Thunderpussy among many others.[32][33] DIY lables like Help Yourself Records[34] and the Sub Pop imprint Hardly Art[35] led the promotion and curation of many emerging PNW acts in this time such as Versing, Dude York, The Moondoggies, and Chastity Belt (band), with other significant bands like Great Grandpa and Special Explosion emerging onto the national indie music scene in the late 2010's. DIY upstarts such as Freakout Records[36] Youth Riot Records,[37] and Den Tapes[38] all also emerged in the late 2010's as champions for local and regional musicians.[39] Other more experimental lables in this period included Hush Hush Records, Sublime Frequencies[40], and the influential Light in the Attic Records, which established itself in Seattle in 2002 and grew to become one of the "most successful re-issue lables in the world" by 2016.[41]

Seattle's electronic music scene and festival scene has also become well known throughout the country as well as internationally. Emerging electronic artists like Chong the Nomad,[42][43] and established acts like the electronic duo Odesza[44] have garnered critical acclaim particularly for their live productions. The Gorge Amphitheatre in George, Washington became an established destination venue for festivals in the Pacific Northwest via the EDM Paradiso Festival held there from 2012-2019, as well as the prominence of Sasquatch! Music Festival from 2002-2018, and the Watershed Music Festival held at the Gorge from 2012-present. Seattle also remains well known today for the Capitol Hill Block Party and Bumbershoot music festivals, both held annually in urban Seattle neighborhoods.[45]

Venues

[edit]Below is a partial list of notable venues:

- Chop Suey

- Conor Byrne Pub

- Crocodile Cafe

- Moore Theatre

- Neptune Theatre

- Neumos

- Paramount Theatre

- The Clock-Out Lounge

- The Sunset Tavern

- The Tractor Tavern

- The Triple Door

- The Vera Project

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Humphrey 1999, p. vii.

- ^ "Seattle City Song". seattle.gov. 2020-06-19. Archived from the original on 2021-09-27.

- ^ Humphrey 1999, pp. 2–3.

- ^ a b De Barros & Calderón 1993.

- ^ Humphrey 1999, pp. 1–2; Humphrey does not cite a specific source for the Beecham incident, but claims that his reported words vary depend "on whose account you read".

- ^ Humphrey 1999, p. 4.

- ^ Keller 2013, p. 11.

- ^ Humphrey 1999, pp. 9–10.

- ^ Humphrey 1999, pp. 11–12.

- ^ "The Tupperwares".

- ^ Tow & Peterson 2011, p. 41.

- ^ Blush & Petros 2001, pp. 263–263.

- ^ Humphrey 1999, pp. vii–viii.

- ^ Garofalo 1997, p. 447 Garofalo also notes Seattle's isolation as a cause of the rise of a distinctive and self-sustained alternative rock scene

- ^ Garofalo 1997, p. 47.

- ^ Blush & Petros 2001, p. 265.

- ^ Garofalo 1997, p. 447.

- ^ Strong 2016, p. 55.

- ^ "KEXP Reaches 500 Million Views on YouTube!". www.kexp.org. Retrieved 2025-02-11.

- ^ Blecha, Peter. "KEXP-FM Radio (Seattle)". www.historylink.org. Retrieved 2025-02-11.

- ^ Alexander, Sean. "After the Show: How KEXP Remains Relevant in a Declining Radio Environment". The Spectator. Retrieved 2025-02-12.

- ^ Vaziri, Aidin. "KEXP amplifies Bay Area presence with KQED partnership, new local music showcase". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on 2024-08-25. Retrieved 2025-02-12.

- ^ Abe, Daudi (2023-08-07). "How Seattle rap crashed the mainstream by swimming against the current". NPR. Retrieved 2025-02-11.

- ^ "Our History". The Crocodile. 2021-02-24. Archived from the original on 2021-05-16.

- ^ "A legendary grunge venue reopens in a new space with larger capacity, more food options and 17 hotel rooms". The Seattle Times. 2021-12-02. Retrieved 2025-02-11.

- ^ Brusse, Holly (2024-12-05). "Creating community at the Vera project". The Seattle Collegian. Retrieved 2025-02-12.

- ^ "The Sunset Tavern is a piece of Ballard history". Seattle Weekly. 2014-09-11. Retrieved 2025-02-12.

- ^ Whiting, Corinne (2024-02-07). "Ballard's beloved Tractor Tavern celebrates 30 years". Seattle Refined. Retrieved 2025-02-12.

- ^ "Seattle's beloved Conor Byrne Pub will reopen under a new business model". The Seattle Times. 2024-07-25. Retrieved 2025-02-12.

- ^ "Seattle's Music Community Is Broken: Here's How We Can Begin to Fix It". The Stranger. Retrieved 2025-02-12.

- ^ Jocom, Juan Miguel (2022-12-24). "Dear The Stranger, Seattle's music scene is not broken, sincerely: The Seattle music scene". The Seattle Collegian. Retrieved 2025-02-12.

- ^ Cortes, Amber (2016-03-31). "Feminist punk scene thrives in Seattle, 'laughing at the patriarchy'". The Seattle Times. Retrieved 2024-01-29.

- ^ May, Emma (2015-11-30). "Forget Flannel: Seattle's New Artistic Hope Is its Feminist Punk Scene". VICE. Retrieved 2024-01-29.

- ^ Henry, Dusty (2019-06-19). "Cassette Crews & Cosmic Cohorts: Seattle's Emerging Labels And Collectives". NPR. Retrieved 2025-02-12.

- ^ "Sub Pops Hardly Art Is Hardly Starving". Seattle Weekly. 2009-09-15. Retrieved 2025-02-12.

- ^ "Watch out, Seattle punks are organizing: Freakout Festival goes nonprofit". The Seattle Times. 2023-05-10. Retrieved 2025-02-12.

- ^ Peterson, Jorn (2022-07-08). "5 Seattle-area Record Labels You Should Know". Seattle Magazine. Retrieved 2025-02-12.

- ^ "Seattle's Den Tapes Cassette Label Celebrates 4 Years of Local Hitmakers and a "No Jerks" Community". kexp.org. Retrieved 2025-02-12.

- ^ Moura, Rob. "Den Tapes' Kay Redden Is the Champion Seattle's DIY Music Scene Needs". The Stranger. Retrieved 2025-02-12.

- ^ Quietus, The (2019-03-14). "The Strange World Of... Sublime Frequencies". The Quietus. Retrieved 2025-02-12.

- ^ Weiss, Passion of the. "How Light In The Attic Became One Of The Most Successful Re-Issue Labels In the World". Forbes. Retrieved 2025-02-11.

- ^ "Meet five Northwest women whose art inspires". king5.com. 2024-03-18. Retrieved 2025-02-11.

- ^ "Your Favorite Producer's Favorite Producer". Billboard. 2024-10-09. Retrieved 2025-02-11.

- ^ "Death Cab for Cutie and ODESZA join forces for a benefit show Saturday in Bellingham, the city where they got their start". The Seattle Times. 2019-05-11. Retrieved 2025-02-11.

- ^ jseattle (2024-07-22). "A Capitol Hill Block Party 2024 hangover: Pike/Pine festival bends but doesn't break despite massive Chappell Roan crowd". CHS Capitol Hill Seattle News. Retrieved 2025-02-12.

Sources

[edit]- Blush, Steven; Petros, George (2001). American Hardcore: A Tribal History. Los Angeles, CA, US: Feral House. ISBN 978-0-922915-71-2. OCLC 48658495 – via Internet Archive.

- De Barros, Paul; Calderón, Eduardo (1993). Jackson Street After Hours: The Roots of Jazz in Seattle. Seattle: Sasquatch Books. ISBN 978-0-912365-86-2. OCLC 28212362.

- Garofalo, Reebee (1997). Rockin' Out: Popular Music in the USA. Boston: Allyn and Bacon. ISBN 978-0-205-13703-9. OCLC 35192297.

- Humphrey, Clark (December 17, 1999). Loser: The Real Seattle Music Story. Art Chantry (photographer) (Second ed.). Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 1-929069-24-3.

- Keller, David (2013). The Blue Note: Seattle's Black Musician's Union, a Pictorial History. Seattle, WA: Our House Publishing. ISBN 978-0-615-86781-6. OCLC 869739663.

- Strong, Catherine (2016). Grunge : music and memory. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-12435-1. OCLC 953862305.

- Tow, Stephen; Peterson, Charles (2011). The Strangest tribe : how a group of Seattle rock bands invented grunge. New York: Sasquatch Books. ISBN 978-1-57061-787-4. OCLC 756484526.