Names of Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka (Sinhala: ශ්රී ලංකා, romanized: Śrī Lankā; Tamil: சிறி லங்கா / இலங்கை, romanized: Ilaṅkai), officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an island country in the northern Indian Ocean which has been known under various names over time.

At the outset of the 6th century BC, Sri Lanka was known as Silam,[1][2] from the Pali Sihalam[2] (or Simhalam,[3] Sihalan,[4] Sihala[5]). It became Saylan mentioned from the 9th century.[6] It was transcribed as Ceilão by the Portuguese in 1505, later in English as Ceylon. Ceylon was used until it was replaced by Sri Lanka in 1972; the honorific Sri has been added to Lanka, a place mentioned in ancient texts and assumed to refer the country between the 10th[7] and the 12th centuries CE.[3]

Other ancient names used to refer to Sri Lanka included Serendip in Persian, Turkic (Serendib/Särändib) and Eelam in Tamil. In the 19th century, it was said that the oldest recorded name of Sri Lanka was Tamraparni.[8] (= Taprobane).

From 6th century BCE to 9th century CE : Silam, Sihala, Sailan

[edit]At the outset of the 6th century BC, Sri Lanka was known as Silam,[1][2] from the Pali Sihalam[2](or Simhalam,[3] Sihalan,[4] Sihala[9]). Silam was transliterated as Sinhale in Sinhala,[10] and Ilam in Tamil (from Silam without the initial sibilant).[4]

In the Dīpavaṃsa (the Buddhist oldest historical record of Sri Lanka, 3rd to 4th century CE), it is written that "The island of Lanka was formerly called Sihala".[11] Sihala means lion's abode[4](from Siha = lion)

In the 2nd century CE, Ptolemy called the inhabitants of the island Salai.[12][13][2] Salai derives from Sihalam (pronounced Silam).[2][1]

In Chinese sources, the Buddhist monk Faxian (3rd and 4th century CE) called the island the Lion Kingdom (師子國) or Sinhala,[14][15] while the 7th century monk Yijing also used the term Lion country (師子洲). Xuanzang called the country Sengjialuo (僧伽羅) for Sinhala in Records of the Western Regions.[16] Lengjia (楞伽) for Lanka was also used.[17]

Cosmas Indicopleustes (6th century CE) named it Σιελεδίβα : Sielediba or SieleDiva[4][2] (Diva, Dwipa meaning Island). Siele also derives from Sihalam.[2] In the 9th century, the forms Sailan and Saylan were used.[6]

Taprobana, Tamraparni

[edit]

Tamraparni is said to be the oldest recorded name of Sri Lanka, for example as asserted by Robert Caldwell.[8] According to some legends, Tamraparni is the name given by Prince Vijaya when he arrived on the island. The word can be translated as "copper-coloured leaf", from the words Thamiram (copper in Sanskrit) and Varni (colour). Another scholar states that Tamara means red and parani means tree, therefore it could mean "tree with red leaves".[18] Tamraparni is also a name of Tirunelveli, the capital of the Pandyan kingdom in Tamil Nadu.[19] The name was adopted in Pali as Tambaparni.

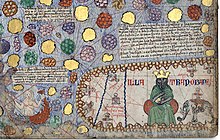

The name was adopted into Greek as Taprobana, used by Megasthenes in the 4th century BC.[20] The Greek name was adopted in medieval Irish (Lebor Gabála Érenn) as Deprofane (Recension 2) and Tibra Faine (Recension 3), off the coast of India, supposedly one of the countries where the Milesians / Gaels, ancestors of today's Irish, had sojourned in their previous migrations.[21][22]

The name remained in use in early modern Europe, alongside the Persianate Serendip, with Traprobana mentioned in the first strophe of the Portuguese national epic poem Os Lusíadas by Luís de Camões.

John Milton borrowed this for his epic poem Paradise Lost and Miguel de Cervantes mentions a fantastic Trapobana in Don Quixote.[23]

Some sources also identify Taprobane with Sumatra.[24]

From 9th century to 15th century CE : Sailan, Saylan, Silan, Seilan

[edit]From Silam came the names :

- Sailan and Saylan, mentioned on the 9th century CE,[6][25]

- Ilam in Tamil[26]),

- Siyalan and Silan (mentioned on the 10th century CE[27]), etc.

Marco Polo, in 1298 CE, names it Seilan.[28] In the Chinese Mao Kun map (17th century but believed to date from the early 15th century), the name appears as Xilan (锡闌), also Xilan (細蘭) in the 13th century Chinese work Zhu Fan Zhi.[29]

During the 13th and 14th centuries, the forms Sailan,[30] Sílán,[31] Sillan,[32] and Seyllan,[33] were used

From the 16th century : Ceilão, Lanka ; Zeylan, Ceylon

[edit]

With the Portuguese colonization in the 16th century, the original local names Silam, Sihala and Sailan were adopted as Ceilão in Portuguese (from 1505), and later as Zeilan or Zeylan in Dutch, and Ceylon in English. After independence in 1948, the name Ceylon was still used until 1972.

Lanka appears later and in parallel, between the 10th[34] and the 12th centuries CE.[3] The name Lanka, a Sanskrit word, comes from the Hindu text the Ramayana, where Lanka is the abode of King Ravana.

The Ramayana Lanka began to be considered as the present-day Sri Lanka between the 10th[34] and the 12th centuries CE.[3] Then from the 16th century, in opposition to colonization, the assertion that the Ramayana Lanka was the present-day Sri Lanka became part of the Sinhalese Buddhist mythology,[34] and started to be used by locals in opposition to the Portuguese colonial name Ceilão.

Sri Lanka

[edit]The name of Sri Lanka was introduced by the Marxist Lanka Sama Samaja Party founded in 1935.

The Sanskrit honorific Sri was introduced in the name of the Sri Lanka Freedom Party (Sinhala: ශ්රී ලංකා නිදහස් පක්ෂය, romanized: Sri Lanka Nidahas Pakshaya) founded in 1952.

In 1972, the Republic of Sri Lanka was officially adopted as the country's name with the new constitution[35] and changed to "Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka" in the constitution of 1978.

Other names

[edit]Serendip

[edit]The names Serendip, Seren-dip, Sarandib or Sarandīp are Persian and Arab[4] or Hindustani[36] names for Sri Lanka suggested to have been derived from the words Sinhala-dvipa (Sinhala Isle, dvipa or dipa means Island), or Suvarna-dvipa meaning "golden-isle".[36] Another proposal suggested the Tamil Cheran (a Tamil tribe) and tivu (island) as the origin.[37] The English word "serendipity" was coined from Serendip.[38][39][40]

Lakdiva

[edit]Another traditional Sinhala name for Sri Lanka was Lakdiva, with diva also meaning "island".[41] A further traditional name is Lakbima.[42] In both cases, Lak is derived from Lanka. The same name could have been adopted in Tamil as Ilangai; the Tamil language commonly adds "i" before initial "l".

Eelam

[edit]The earliest use of the word is found in a Tamil-Brahmi inscription as well as in the Sangam literature. The Tirupparankunram inscription found near Madurai in Tamil Nadu and dated on palaeographical grounds to the 1st century BCE, refers to a person as a householder from Eelam (Eela-kudumpikan).[43]

The most favoured explanation derives it from a word for the spurge (palm tree),[44] via the application to a caste of toddy-drawers, i.e. workers drawing the sap from palm trees for the production of palm wine.[45] The name of the palm tree may conversely be derived from the name of the caste of toddy drawers, known as Eelavar, cognate with the name of Kerala, from the name of the Chera dynasty, via Cheralam, Chera, Sera and Kera.[46][47][unreliable source?]

The stem Eela is found in Prakrit inscriptions dated to 2nd century BC in Sri Lanka in personal names such as Eela-Vrata/Ela-Bharat and Eela-Naga.[citation needed] The meaning of Eela in these inscriptions is unknown although one could deduce that they are either from Eela a geographic location or were an ethnic group known as Eela.[48][unreliable source?][49] From the 19th century onwards, sources appeared in South India regarding a legendary origin for caste of toddy drawers known as Eelavar in the state of Kerala. These legends stated that Eelavar were originally from Eelam.

There have also been proposals of deriving Eelam from Simhala (comes from Elam, Ilam, Tamil, Helmand River, Himalayas). Robert Caldwell (1875), following Hermann Gundert, cited the word as an example of the omission of initial sibilants in the adoption of Indo-Aryan words into Dravidian languages.[50] The University of Madras Tamil Lexicon, compiled between 1924 and 1936, follows this view.[44] Peter Schalk (2004) has argued against this, showing that the application of Eelam in an ethnic sense arises only in the early modern period, and was limited to the caste of "toddy drawers" until the medieval period.[45]

Thomas Burrow, in contrast, argued that the word was likely to have been Dravidian in origin, on the basis that Tamil and Malayalam "hardly ever substitute (Retroflex approximant) 'ɻ' peculiarly Dravidian sound, for Sanskrit -'l'-." He suggests that the name "Eelam" came from the Dravidian word "Eelam" (or Cilam) meaning "toddy", referring to the palm trees in Sri Lanka, and later absorbed into Indo-Aryan languages. This, he says, is also likely to have been the source for the Pali '"Sihala".[51] The Dravidian Etymological Dictionary, which was jointly edited by Thomas Burrow and Murray Emeneau, marks the Indo-Aryan etymology with a question mark.[52]

Suggested Biblical names

[edit]- Tarshish. According to James Emerson Tennent, Galle was said to be the ancient city of Tarshish where King Solomon drew ivory, peacocks, and others. Cinnamon was exported from Sri Lanka as early as 1400 BC and as the root of the word cinnamon itself is Hebrew,[53] Galle may have been the port of entry for the spice.[54]

- Ophir. There is a Jewish tradition that associates the land of Ophir with modern-day India and Sri Lanka. David ben Abraham al-Fasi, a 10th-century lexicographer, cites Ophir as Serendip, as the country was known to the Persians.[55]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Cosmas (Indicopleustes), The Christian Topography of Cosmas, an Egyptian Monk: Translated from the Greek, and Edited with Notes and Introduction, Hakluyt Society, 1897, p. 363

- ^ a b c d e f g h J. W. McCrindle, Hakluyt Society, Works Issued by the Hakluyt Society, B. Franklin, Volume 98, 1897

- ^ a b c d e J. Dodiya, Critical Perspectives on the Rāmāyaṇa, Sarup & Sons, 2001, p. 166-181

- ^ a b c d e f Henry Yule, A. C. Burnell, Hobson-Jobson : The Anglo-Indian Dictionary, 1903

- ^ S. K. Aiyangar, Some Contributions of South India to Indian Culture, Asian Educational Services, 1995

- ^ a b c R. A. Donkin, Beyond Price: Pearls and Pearl-fishing, Origins to the Age of Discoveries, American Philosophical Society, 1998

- ^ Dr. Deborah de Koning, PhD (2022), "Ravanisation": The Revitalisation of Ravana among Sinhalese Buddhists in Post-War Sri Lanka, LIT Verlag, Münster, pages 108-110

- ^ a b Caldwell, Robert (1989). A History of Tinnevelly. Asian Educational Services. pp. 9–10. ISBN 978-81-206-0161-1.

- ^ S. K. Aiyangar, Some Contributions of South India to Indian Culture, Asian Educational Services, 1995

- ^ M. M. M. Mahroof, An Ethnological Survey of the Muslims of Sri Lanka: From Earliest Times to Independence, Sir Razik Fareed Foundation, 1986, p. XVI

- ^ Donald W. Ferguson, The Indian Antiquary, A journal of Oriental Research, Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Archæological Survey of India, 1884, Volume 13, page 34

- ^ Ven. Dr. Kalalelle Sekhara, Early Buddhist Saghas and Viharas in Sri Lanka (up to 4th century A.D.),

- ^ Indicopleustes, Cosmas; McCrindle, J. W. (24 June 2010). The Christian Topography of Cosmas, an Egyptian Monk: Translated from the Greek, and Edited with Notes and Introduction. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-01295-9.

- ^ "佛國記". CBETA.

- ^ J. Barthelemy Saint-Hilaire (1860), Le Bouddha et sa religion, page 321

- ^ "斯里兰卡奇迹之旅".

- ^ Raguin, Yves (1985). Terminologie raisonée du bouddhisme chinois. Association Française pour le Développement Culturel et Scientifique en Asie. p. 223.

- ^ Caldwell, Bishop R. (1 January 1881). History of Tinnevelly. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 9788120601611.

- ^ Arumugam, Solai; GANDHI, M. SURESH (1 November 2010). Heavy Mineral Distribution in Tamiraparani Estuary and Off Tuticorin. VDM Publishing. ISBN 978-3-639-30453-4.

- ^ Friedman, John Block; Figg, Kristen Mossler (4 July 2013). Trade, Travel, and Exploration in the Middle Ages: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-59094-9. Archived from the original on 15 October 2018. Retrieved 17 March 2016.

- ^ Macalister, Robert Alexander Stewart (1 September 1939). "Lebor Gabála Érenn: The Book of the Taking of Ireland – Volume 2 (1939)". Retrieved 1 September 2023 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ In the early 1800s, Welsh pseudohistorian Iolo Morganwg published what he claimed was mediaeval Welsh epic material, describing how Hu Gadarn had led the ancestors of the Welsh in a migration to Britain from Taprobane or "Deffrobani", aka "Summerland", said in his text to be situated "where Constantinople now is." However, this work is now considered to have been a forgery produced by Iolo Morganwg himself.

- ^ Don Quixote, Volume I, Chapter 18: the mighty emperor Alifanfaron, lord of the great isle of Trapobana.

- ^ Van Duzer, C. (2020). "The Long Legends: Transcription, Translation, and Commentary". Martin Waldseemüller's 'Carta marina' of 1516. pp. 55–150. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-22703-6_2. ISBN 978-3-030-22702-9.

- ^ mentioned by Al-Jahiz in 868

- ^ Robert Caldwell (1989), A History of Tinnevelly, pages 9 and 10

- ^ Buzurg Ibn Shahriyar, Kitāb ‘Ajāyab-ul-Hind or Livre des Merveilles de l’Inde, Text Arab par P.A. Van der Lith, traduction francaise L. M. Devic, E.J. Brill, (Leiden, 1883–1886), p. 124, p. 265.

- ^ Marco Polo, Book III, chapiter 14.

- ^ Yang, Shao-yun (August 2024). "A Chinese Gazetteer of Foreign Lands: A new translation of Part 1 of the Zhufan zhi 諸蕃志 (1225)".

- ^ in 1275, Kazvini, Gildemeister, 203

- ^ Rashíduddín, in Elliot, I. 70.

- ^ Odoric of Pordenone, in Cathay and the Way Thither, I, 98.

- ^ Giovanni de' Marignolli, in Cathay and the Way Thither, II, 346.

- ^ a b c Dr. Deborah de Koning, PhD (2022), "Ravanisation": The Revitalisation of Ravana among Sinhalese Buddhists in Post-War Sri Lanka, LIT Verlag, Münster, pages 108–110

- ^ Articles 1 and 2 of the 1972 constitution: "1. Sri Lanka (Ceylon) is a Free, Sovereign and Independent Republic. 2. The Republic of Sri Lanka is a Unitary State."

- ^ a b Goodman, Leo A. (May 1961). "Notes on the Etymology of Serendipity and Some Related Philological Observations". Modern Language Notes. 76 (5): 454–457. doi:10.2307/3040685. JSTOR 3040685.

- ^ Sachi Sri Kantha (January 2016). "Serendipity: a synopsis of its 260 year life as an English word". doi:10.13140/RG.2.1.1107.8163.

- ^ Ramachandran, M.; Mativāṇan̲, Irāman̲ (1 January 1991). The spring of the Indus civilisation. Prasanna Pathippagam. p. 62.

- ^ Barber, Robert K. Merton, Elinor (2006). The Travels and Adventures of Serendipity : A Study in Sociological Semantics and the Sociology of Science (Paperback ed.). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. pp. 1–3. doi:10.1515/9781400841523.1. ISBN 0-691-12630-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Boyle, Richard (30 July 2000). "The Three Princes of Serendip". The Sunday Times.

- ^ Silvā, Ṭī Em Jī Es (1 January 2001). Lakdiva purāṇa koḍi (in Sinhala). Sūriya Prakāśakayō. ISBN 9789558425398.

- ^ Bandara, C. M. S. J. Madduma (1 January 2002). Lionsong: Sri Lanka's Ethnic Conflict. Sandaruwan Madduma Bandara. ISBN 9789559796602.

- ^ Civattampi, Kārttikēcu (2005). Being a Tamil and Sri Lankan. Aivakam. pp. 134–135. ISBN 9789551132002.

- ^ a b University of Madras (1924–1936). "Tamil lexicon". Madras: University of Madras. Archived from the original on 12 December 2012.

- ^ a b Schalk, Peter (2004). "Robert Caldwell's Derivation īlam < sīhala: A Critical Assessment". In Chevillard, Jean-Luc (ed.). South-Indian Horizons: Felicitation Volume for François Gros on the occasion of his 70th birthday. Pondichéry: Institut Français de Pondichéry. pp. 347–364. ISBN 2-85539-630-1..

- ^ Nicasio Silverio Sainz (1972). Cuba y la Casa de Austria. Ediciones Universal. p. 120. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- ^ M. Ramachandran, Irāman̲ Mativāṇan̲ (1991). The spring of the Indus civilisation. Prasanna Pathippagam, pp. 34. "Srilanka was known as "Cerantivu' (island of the Cera kings) in those days. The seal has two lines. The line above contains three signs in Indus script and the line below contains three alphabets in the ancient Tamil script known as Tamil ...

- ^ Akazhaan. "Eezham Thamizh and Tamil Eelam: Understanding the terminologies of identity". Tamilnet. Retrieved 2 October 2008.

- ^ Indrapala, Karthigesu (2007). The evolution of an ethnic identity: The Tamils in Sri Lanka C. 300 BCE to C. 1200 CE. Colombo: Vijitha Yapa. ISBN 978-955-1266-72-1.p. 313

- ^ Caldwell, Robert (1875). A comparative grammar of the Dravidian or South-Indian Family of Languages. London: Trübner & Co. p. pt. 2 p. 86.

- ^ Burrow, Thomas (1947). "Dravidian Studies VI — The loss of initial c/s in South Dravidian". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 12 (1): 132–147. doi:10.1017/s0041977x00079969. JSTOR 608991. S2CID 162621555. at p. 133

- ^ Burrow, T.A.; Emeneau, M.B., eds. (1984). "A Dravidian Etymological Dictionary" (2nd ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. Archived from the original on 7 July 2012. (Online edition at the University of Chicago)

- ^ "Cinnamon". A Dictionary of First Names. Oxford University Press. January 2006. ISBN 978-0-19-861060-1.

- ^ https://web.archive.org/web/20140728201052/http://www.econsortium.info/Psychosocial_Forum_District_Data_Mapping/galle.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ Culture (4 October 2020). "Does the Bible Make Reference to Sri Lanka and South India? | Indo-Christian". medium.com. Retrieved 1 September 2023.

External links

[edit]![]() The dictionary definition of names of sri lanka at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of names of sri lanka at Wiktionary