Siege of Ma'arra

| Siege of Ma'arra | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the First Crusade | |||||||

Capture of the fortress of Ma'arra in the province of Antioch in 1098 by 19th-century painter Henri Decaisne | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Crusaders | City in the realm of Ridwan of Aleppo | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Raymond IV of Toulouse Bohemond of Taranto Robert II of Flanders | Unknown | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Unknown | Local militia and garrison | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| About 20,000 civilians killed | |||||||

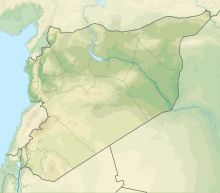

Location within Syria | |||||||

The siege of Ma'arra occurred in late 1098 in the city of Ma'arrat Nu'man, in what is modern-day Syria, during the First Crusade. It is infamous for the claims of widespread cannibalism committed by the Crusaders.

Background

[edit]The First Crusaders, including Raymond IV of Toulouse and Bohemond of Taranto, launched the siege of Antioch in October 1097.[1][2] That December, Bohemond and Robert II of Flanders led 20,000 men to forage and plunder the surrounding countryside of food, opening Raymond IV to counterattack by Seljuk Empire commander and Antioch governor Yaghi-Siyan.[3] The crusaders were suffering widespread hunger by early 1098.[4]

In July 1098, Raymond Pilet d'Alès, a knight in Raymond IV's army, led an expedition against Ma'arra, an important city on the road south towards Damascus. His troops met a much larger Muslim garrison in the town, and they were routed with many casualties.[5] For the rest of the summer, the Crusaders continued their march south, captured many other small towns, and arrived again at Ma'arra in November.

Siege

[edit]On the morning of November 28, 1098, Raymond IV and Robert II, Count of Flanders, launched an unsuccessful assault on Ma'arra. Bohemond joined them that afternoon and attempted a second unproductive attack.[6] The citizens were initially unconcerned since Raymond Pilet's expedition had failed, and they taunted the Crusaders. The Crusaders could also not afford to conduct a lengthy siege, as winter was approaching and they had few supplies, but they were also unable to break through the city's defences, consisting of a deep ditch and strong walls.

The defenders of the city, mostly an urban militia and inexperienced citizens, managed to hold off the attacks for about two weeks.[6] The Crusaders repeatedly sent envoys offering terms of surrender that included security of the Arab population's lives and properties in return for the establishment of a Frankish governor of the city.[7] These terms were rejected. The crusaders spent this time building a siege tower, which allowed them to pour over the walls of the city,[6] while at the same time, a group of knights scaled the undefended walls on the other side of the city.

The Crusaders used the siege tower to destroy a wall on December 11 and began pillaging. The fighting subsided for the night but resumed in a brutal plunder the following morning. Some Muslims negotiated a surrender to Bohemond; these men were killed, and the women and children were enslaved and sold.[8] Meanwhile, Bohemond seized most of the loot. However, Raymond's army had largely secured the city, resulting in the latter claiming the fortification for the bishop of Albara. The armies remained stationary until January 13, 1099, when they resumed the march south to take Jerusalem.[9]

Cannibalism

[edit]

During or after the siege, some of the starving crusaders resorted to cannibalism, feeding on the bodies of Muslims. This fact itself is not seriously in doubt, as it is acknowledged by nearly a dozen Christian chronicles written during the twenty years after the Crusade, all of which are based at least to some degree on eyewitness accounts.[10] The crusaders' cannibalism is also briefly mentioned in an Arab source, which explains it as due to hunger ("racked by dearth").[11]

There is conflicting evidence on when exactly and why the cannibalism happened. Some sources state that enemies were eaten during the siege, while others (a slight majority) state that it happened after the city had been conquered.[12] Another source of tension exists regarding its motives – was it practised secretly due to famine and lack of food, as some sources suggest, or publicly in front of the enemies to shock and frighten them, as others imply?[13]

After the city's fall, the Crusaders stayed there for about a month before continuing their march to Jerusalem while their leaders debated how to divide the lands they had conquered.[14] One group of chronicles suggests that the cannibalism occurred after the end of the siege and was entirely motivated by hunger. The earliest text in this tradition, the Gesta Francorum, states that because of great deprivations after the siege, "Some cut the flesh of dead bodies into strips and cooked them for eating." Peter Tudebode's chronicle gives a similar description, though adding that only Muslims were eaten.[15] Several other works that are partially based on the Gesta Francorum include similar accounts, likewise stating that only Muslims or "Turks" were consumed. Only one of them says that "human flesh was being traded openly", while the others imply that it was only eaten discreetly, out of sight.[16]

Raymond of Aguilers, who seems to have been present at Ma'arra, likewise states that the cannibalism happened after the siege and "in the midst of famine", but adds that human flesh was consumed in public and "with gusto" rather than secretly and shamefully. He adds that these spectacles shocked the Muslims who were terrified by the resolution and cruelty of the crusaders – which is somewhat at odds with his account that these events happened after the fall of the city when all Muslims in the vicinity were either dead or enslaved.[17]

Three other accounts, by Fulcher of Chartres (who was a participant of the Crusade though not personally present at Ma'arra), Albert of Aachen and Ralph of Caen (both of whom based their accounts on interviews with participants) state that the cannibalism happened during the siege and suggest that it was a public spectacle rather than a shameful, hidden episode.[18] Ralph states that "a lack of food compelled them to make a meal of human flesh, that adults were put in the stewpot, and that [children] were skewered on spits. Both were cooked and eaten." He asserts that he heard this "from the very perpetrators of this shame", that is, from some of the cannibals themselves.[19] Albert writes "that the Christians, in the face of the scarcity about which you have heard, did not fear to eat ... the bodies, cooked in fire, not only of the Saracens or Turks they had killed, but also of the dogs that they had caught", thus cynically implying that eating dogs was worse than eating Muslims.[20] Fulcher states that many crusaders "savagely filled their mouths" with cooked "pieces from the buttocks of the Saracens" which they had cut from the bodies of enemies while the siege was still ongoing.[21]

While multiple sources concur on the fact of the cannibalism, both its timing and its motives are thus in doubt. Another issue is whether such acts were limited to Ma'arra or happened also elsewhere during the First Crusade, as several accounts suggest. Some sources describe cannibalism several months earlier, during the siege of Antioch.[22] The Byzantine princess Anna Komnene ascribes it to an even earlier period, the People's Crusade, and describes it in a way similar to Ralph of Caen: "they cut in pieces some of the babies, impaled others on wooden spits, and roasted them over a fire".[23]

Several medieval interpretations of cannibalism during the Crusade, by Guibert of Nogent, William of Tyre, and in the Chanson d'Antioche, interpret it as a deliberate act of psychological warfare, "intended to strike fear in the enemy". This implies it must have happened during rather than after the siege, "while there were still Muslims alive to witness it and to feel the horror that was its intended by-product".[24]

In concluding his discussion of the various accounts of the cannibalism, historian Jay Rubenstein notes that the chroniclers felt discomfort and tried to downplay what had happened, hence tending to give only part of the facts (but without agreeing on which part and interpretation to give).[25] He also notes that the fact that only Muslims were eaten is at odds with hunger as a sole or primary motive – presumably, desperate starving people would not have cared much about the religion of those they consumed.[26] He concludes that Ma'arra was probably only "the most memorable instance of what was likely a periodic response to famine", namely cannibalism, and that it went "beyond poor and hungry people eating from the dead" in secret. He rather supposes that "some of the soldiers must have recognized its potential utility [as a weapon of terror] and, hoping to drive the defenders into a quick surrender, made a spectacle of the eating, and made sure that Muslims were the only ones eaten."[25]

Historian Thomas Asbridge states that, while the "cannibalism at Marrat is among the most infamous of all the atrocities perpetrated by the First Crusaders", it nevertheless had "some positive effects on the crusaders' short-term prospects". Reports and rumours of their brutality in Ma'arra and Antioch convinced "many Muslim commanders and garrisons that the crusaders were bloodthirsty barbarians, invincible savages who could not be resisted". Accordingly, many of them decided to "accept costly and humiliating truces with the Franks rather than face them in battle".[27]

Controversy about the role of the Tafurs

[edit]Some chroniclers, as well as various later sources, blamed the cannibalism at Ma'arra on the Tafurs, a group of crusaders who followed strict oaths of poverty. In recent times, several scholars have continued to identify the Tafurs as the chief perpetrators of cannibalism.[28] Guibert of Nogent was the first to attribute cannibal acts specifically to the Tafurs, at the same time downplaying their significance and declaring that they happened – if at all – only in secret.[29] In the later Chanson d'Antioche, however, the Tafurs reappear as fanatics who "roast Saracen bodies on spits just outside Antioch's walls", shocking the defenders.[30] Rubenstein concludes that a desire of some chroniclers "to blame the poor for the cannibalism ... led them to create the Tafur mythology"[31] and that this mythology flourished in later times because it helped isolate the unpleasant memories of the crusader cannibalism from the armed, heroic crusaders themselves, instead squarely blaming it on a group of poor, unarmed helpers.[32]

Among modern historians, Amin Maalouf is probably the best known who upheld the Tafur thesis:

The inhabitants of the Ma'arra region witnessed behaviour during that sinister winter that could not be accounted for by hunger. They saw, for example, fanatical Franj, the Tafurs, roam through the country-side openly proclaiming that they would chew the flesh of the Saracens and gathering around their nocturnal camp-fires to devour their prey.[33]

Maalouf also notes that the events at Ma'arra helped shape a negative image of the Crusaders in Arab eyes. "For three days they put people to the sword, killing more than a hundred thousand people", one Arab chronicler wrote. While this was widely exaggerated, as the whole city's population had probably been less than ten thousand, it indicates an amount of violence that deeply shocked the Muslim world, while the "barely imaginable fate" of the bodies of victims – to serve as food for the conquerors – was an even more profound shock. After these events, the "Franj" frequently appear in Arab and Turkish sources as brutal "beasts" and "anthropophagi".[34]

Maalouf's argument has come under criticism by other scholars. Rubenstein agrees with him that "Arab historians do remember Ma'arra as the scene of a horrific massacre", but he criticizes Maalouf's claim that "oral tradition" preserved the cannibalistic horrors among the Arabs as "probably an argumentative sleight of hand", pointing out that it was Christian rather than Arab chroniclers who recorded and documented the cannibalism – and that it was some of them, not Arabs, who specifically blamed the Tafurs.[35] Carine Bourget agrees with Maalouf that the tendency of major 20th-century accounts of the crusades to downplay or altogether omit the cannibal episode is problematic,[36] but she reproaches him for engaging in a "rewriting of history" of another kind, by not mentioning the single Arab source that mentions the cannibalism and explains it as due to hunger, to strengthen his "fanaticism" conjecture.[11]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Edgington, Susan; Sweetenham, Carol, eds. (2011). The Chanson D'Antioche: An Old French Account of the First Crusade. Routledge. p. 391.

- ^ Barker, Ernest (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 4 (11th ed.). pp. 135–136.

- ^ Asbridge 2004, p. 248.

- ^ Runciman 1951, pp. 220–223.

- ^ Asbridge 2004, pp. 248–249.

- ^ a b c Runciman 1951, p. 259.

- ^ Asbridge, Thomas (2017). "Knowing the Enemy: Latin Relations with Islam at the Time of the First Crusade". In Housley, Norman (ed.). Knighthoods of Christ: Essays on the History of the Crusades and the Knights Templar, Presented to Malcolm Barber. London: Routledge. Ch. 2. ISBN 978-1-351-92392-7.

- ^ Runciman 1951, pp. 259–260.

- ^ Runciman 1951, pp. 260–261.

- ^ Rubenstein 2008, pp. 526, 537.

- ^ a b Bourget 2006, p. 269.

- ^ Rubenstein 2008, p. 537.

- ^ Rubenstein 2008, pp. 533, 535, 541.

- ^ Rubenstein 2008, p. 526.

- ^ Rubenstein 2008, pp. 530–531.

- ^ Rubenstein 2008, pp. 532–533.

- ^ Rubenstein 2008, pp. 534–535.

- ^ Rubenstein 2008, pp. 534–536.

- ^ Rubenstein 2008, p. 536.

- ^ Rubenstein 2008, p. 535.

- ^ Rubenstein 2008, p. 534.

- ^ Rubenstein 2008, pp. 537–538.

- ^ Rubenstein 2008, pp. 538–539.

- ^ Rubenstein 2008, pp. 539–542.

- ^ a b Rubenstein 2008, p. 550.

- ^ Rubenstein 2008, p. 529.

- ^ Asbridge 2004, pp. 274–275.

- ^ Rubenstein 2008, pp. 526–527.

- ^ Rubenstein 2008, pp. 539–540.

- ^ Rubenstein 2008, p. 541.

- ^ Rubenstein 2008, p. 530.

- ^ Rubenstein 2008, pp. 540, 551–552.

- ^ Maalouf, Amin (1984). The Crusades Through Arab Eyes. London: Al Saqi Books. p. 39. ISBN 0-86356-113-6.

- ^ Maalouf 1984, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Rubenstein 2008, p. 527.

- ^ Bourget 2006, pp. 268 and 282 (note 4).

Bibliography

[edit]- Asbridge, Thomas (2004). The First Crusade: A New History. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-517823-4.

- Bourget, Carine (2006). "The Rewriting of History in Amin Maalouf's The Crusades Through Arab Eyes". Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature. 30 (2, Article 3): 263–287. doi:10.4148/2334-4415.1633. Archived from the original on 19 July 2018.

- Rubenstein, Jay (2008). "Cannibals and Crusaders". French Historical Studies. 31 (4): 525–552. doi:10.1215/00161071-2008-005.

- Runciman, Steven (1951). The History of the Crusades Volume I: The First Crusade and the Foundation of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. Cambridge University Press.

Further reading

[edit]- Heng, Geraldine (2003). Empire of Magic: Medieval Romance and the Politics of Cultural Fantasy. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Lebedev, Claude (2006). Les Croisades, origines et consequences. Éditions Ouest-France. ISBN 2-7373-4136-1.