Slogan

A slogan is a memorable motto or phrase used in a clan or a political, commercial, religious, or other context as a repetitive expression of an idea or purpose, with the goal of persuading members of the public or a more defined target group. The Oxford Dictionary of English defines a slogan as "a short and striking or memorable phrase used in advertising".[1] A slogan usually has the attributes of being memorable, very concise and appealing to the audience.[2]

Etymology

[edit]The word slogan is derived from slogorn, which was an Anglicisation of the Scottish Gaelic and Irish sluagh-ghairm (sluagh 'army', 'host' and gairm 'cry').[3] George E. Shankel's (1941, as cited in Denton 1980) research states that "English-speaking people began using the term by 1704". The term at that time meant "the distinctive note, phrase or cry of any person or body of persons". Slogans were common throughout the European continent during the Middle Ages; they were used primarily as passwords to ensure proper recognition of individuals at night or in the confusion of battle.[4]

Likability

[edit]Crimmins' (2000, as cited in Dass, Kumar, Kohli, & Thomas, 2014) research suggests that brands are an extremely valuable corporate asset, and can constitute much of a business's total value. With this in mind, if we take into consideration Keller's (1993, as cited in Dass, Kumar, Kohli, & Thomas, 2014) research, which suggests that a brand is made up of three different components. These include, name, logo and slogan. Brands names and logos both can be changed by the way the receiver interprets them. Therefore, the slogan has a large job in portraying the brand (Dass, Kumar, Kohli, & Thomas, 2014).[5] Therefore, the slogan should create a sense of likability in order for the brand name to be likable and the slogan message very clear and concise.

Dass, Kumar, Kohli, & Thomas' (2014) research suggests that there are certain factors that make up the likability of a slogan. The clarity of the message the brand is trying to encode within the slogan. The slogan emphasizes the benefit of the product or service it is portraying. The creativity of a slogan is another factor that had a positive effect on the likability of a slogan. Lastly, leaving the brand name out of the slogan will have a positive effect on the likability of the brand itself.[5] Advertisers must keep into consideration these factors when creating a slogan for a brand, as it clearly shows a brand is a very valuable asset to a company, with the slogan being one of the three main components to a brands' image.

Usage

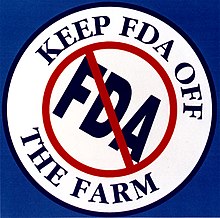

[edit]The original usage refers to the usage as a clan motto among Gaelic armies. Marketing slogans are often called taglines in the United States or straplines in the United Kingdom. Europeans use the terms baselines, signatures, claims or pay-offs.[6] "Sloganeering" is a mostly derogatory term for activity which degrades discourse to the level of slogans.[7]

Slogans are used to convey a message about the product, service or cause that it is representing. It can have a musical tone to it or written as a song. Slogans are often used to capture the attention of the audience it is trying to reach. If the slogan is used for commercial purposes, often it is written to be memorable/catchy in order for a consumer to associate the slogan with the product it is representing.[8][9] A slogan is part of the production aspect that helps create an image for the product, service or cause it is representing. A slogan can be a few simple words used to form a phrase that can be used in a repetitive manner. In commercial advertising, corporations will use a slogan as part of promotional activity.[9] Slogans can become a global way of identifying a good or service, for example Nike's slogan 'Just Do It' helped establish Nike as an identifiable brand worldwide.[10]

Slogans should catch the audience's attention and influence the consumer's thoughts on what to purchase.[11] The slogan is used by companies to affect the way consumers view their product compared to others. Slogans can also provide information about the product, service or cause it is advertising. The language used in the slogans is essential to the message it wants to convey. Current words used can trigger different emotions that consumers will associate that product with.[11] The use of good adjectives makes for an effective slogan; when adjectives are paired with describing nouns, they help bring the meaning of the message out through the words.[12] When a slogan is used for advertising purposes its goal is to sell the product or service to as many consumers through the message and information a slogan provides.[13] A slogan's message can include information about the quality of the product.[13] Examples of words that can be used to direct the consumer preference towards a current product and its qualities are: good, beautiful, real, better, great, perfect, best, and pure.[14] Slogans can influence that way consumers behave when choosing what product to buy.

Slogans offer information to consumers in an appealing and creative way. A slogan can be used for a powerful cause where the impact of the message is essential to the cause.[15][16] The slogan can be used to raise awareness about a current cause; one way is to do so is by showing the truth that the cause is supporting.[16] A slogan should be clear with a supporting message. Slogans, when combined with action, can provide an influential foundation for a cause to be seen by its intended audience.[17] Slogans, whether used for advertising purpose or social causes, deliver a message to the public that shapes the audiences' opinion towards the subject of the slogan.

"It is well known that the text a human hears or reads constitutes merely 7% of the received information. As a result, any slogan merely possesses a supportive task." (Rumšienė & Rumšas, 2014).[18] Looking at a slogan as a supportive role to a brand's image and portrayal is helpful to understand why advertisers need to be careful in how they construct their slogan, as it needs to mold with the other components of the brand image, being logo and name. For example, if a slogan was pushing towards "environmentally friendly", yet the logo and name seemed to show very little concern for the environment, it would be harder for the brand to integrate these components into a successful brand image, as they would not integrate together towards a common image.

In Protest

[edit]Slogans have been used widely in protests dating back hundreds of years, however increased rapidly following the advent of mass media, particularly with the creation the Gutenberg's printing press and later modern mass media in the early 20th century. Examples of slogans being used in the context of protest in antiquity include the Nika revolt, in which the cry "Nika!" (victory in Greek) was used as a rallying tool and nearly brought down the Byzantine Empire under Justinian I. The basis of slogans have been noted by many political figures and dictators have also noted its effectiveness, in Hitler's Mein Kampf he notes to tell and repeat the same talking points without any regard to if they have any philosophical or factual basis in reality, advising to state "big lies" in politics.[19][20]

The basis of this simple propaganda effect was used by the Nazi and Soviet regimes as noted in their propaganda posters.[21][22][23] In contrast, slogans are oftentimes used in liberal democracies as well as grassroot organisation, in a campaign setting. With the increasing speed and quantity of information in the modern age, slogans have become a mainstay of any campaign, often used by Unions while on strike to make their demands immediately clear.

This has been noted by many scholars, as an example Noam Chomsky notes of the worrying fusion of media and reality in Manufacturing Consent Chomsky discusses this basis as well the potential dangers of this, particularly towards the context of corporations and producing advertisements that either seek to empower or exclude the viewer to encourage an in-group mentality with the goal of getting the viewer to consume. While Manufacturing Consent addresses the use of slogans in the context of national propaganda, Chomsky argues that national and capitalist propaganda are inherently linked and are not clearly exclusive to each other.[24] They are often used in disinformation campaigns, as quick immediate forms of propaganda suited well to modern forms of social media. Earlier writers such George Orwell notes the effective use of quick non-critical slogans to produce a servile population, written primarily in 1984 as a general critique of the manipulation of language.[25]

Politics and racism

[edit]Slogans are often used as a way to dehumanize groups of people. In the United States as anti-communist fever took hold in the 1950s, the phrase "Better dead than Red" became popular anti-communist slogan in the United States, especially during the McCarthy era.[26]

Death to America is an anti-American political slogan and chant. It is used in Iran.[27] Death to Arabs is an anti-Arab slogan which is used by some Israelis.[28]

References

[edit]- ^ Stevenson, A. (2010). Oxford Dictionary of English (Vol. III). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780199571123.001.0001. ISBN 978-0199571123.

- ^ Lim, L.; Loi (2015). "Evaluating slogan translation from the readers' perspective: A case study of Macao". Babel. doi:10.1075/babel.61.2.07lim.

- ^ Merriam-Webster (2003), p. 1174. Irish

- ^ Denton, R. E. Jr. (1980). "The Rhetorical Function of Slogans: Classification and Characteristics". Communication Quarterly. 28 (2): 10–18. doi:10.1080/01463378009369362.

- ^ a b Dass, Mayukh; Kohli, Chiranjeev; Kumar, Piyush; Thomas, Sunil (2014-12-01). "A study of the antecedents of slogan liking". Journal of Business Research. 67 (12): 2504–2511. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2014.05.004.

- ^ Foster, Timothy R. V. "The Art and Science of the Advertising Slogan". adslogans.co.uk.

- ^ Daly, Kathleen (1993). "Class-Race-Gender: Sloganeering in Search of Meaning". Social Justice. 20 (1/2 (51-52)): 56–71. JSTOR 29766732.

- ^ Ke, Qunsheng; Wang, Weiwei (1 February 2013). "The Adjective Frequency in Advertising English Slogans". Theory and Practice in Language Studies. 3 (2). CiteSeerX 10.1.1.735.7047. doi:10.4304/tpls.3.2.275-284.

- ^ a b Ke. Wang 2013, p. 276.

- ^ "Lewis Silkin - Error 404". Lewis Silkin.

- ^ a b Ke. Wang 2013, p. 277.

- ^ Ke. Wang 2013, p. 278.

- ^ a b Ke. Wang 2013, p. 279.

- ^ Ke. Wang 2013, pp. 278–280.

- ^ Kohl F. David. (2011). Getting the Slogan Right. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 37(3), 195–196

- ^ a b Kohl 2011, p. 195.

- ^ Colla, E. (2014). The People Want. Middle East Research and Information Project. Retrieved from www.merip.org/mer/mer263/people-want.

- ^ Rumšienė, G. R.; Rumšas (2014). "Shift of emphasis in advertisement slogan translation". Language in Different Contexts / Kalba Ir Kontekstai.

- ^ "Mein Kampf (My Struggle)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-12-02. Retrieved 2021-11-28.

- ^ Marjorie Van de Water (1938). "Propaganda". The Science News-Letter. 34 (15): 234–235. doi:10.2307/3914714. JSTOR 3914714.

- ^ Lasswell, Harold D. (1951). "The Strategy of Soviet Propaganda". Proceedings of the Academy of Political Science. 24 (2): 66–78. doi:10.2307/1173235. JSTOR 1173235.

- ^ Michael, Robert; Doerr, Karin (2002). "Nazi-Deutsch/Nazi German: An English Lexicon of the Language of the Third Reich" (PDF). Arild Hauges Runer.

- ^ Doob, Leonard W. (1950). "Goebbels' Principles of Propaganda". Public Opinion Quarterly. 14 (3): 419. doi:10.1086/266211. S2CID 145615085.

- ^ Zhang, Yonghong; Lee, Ching Kwan (July 15, 2019). "Manufacturing Consent: How Grassroots Government Assimilates Public Resistance". Urban Chinese Governance, Contention, and Social Control in the New Millennium: 6–38. doi:10.1163/9789004408616_003. ISBN 9789004408623. S2CID 203154512 – via brill.com.

- ^ "The functions of the narrative structure in Nineteen-eighty four: A look into the three-part novel and its relation to the author's warning message. Federal University of Technology – Paraná, By: Maior, Felipe Souto, 28 February 2014" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 December 2021. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

- ^ Coiner, Constance (1998). Better Red: The Writing and Resistance of Tillie Olsen and Meridel Le Sueur (Illini Books ed.). Urbana: University of Illinois Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-252-06695-5. LCCN 97039933.

- ^ Arash Karami: Khomeini Orders Media to End 'Death to America' Chant Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine, Iran Pulse, October 13, 2013

- ^ Mackey, Robert. "Israel's New Leaders Won't Stop "Death to Arabs" Chants, but They Will Feel Bad About Them". The Intercept. Retrieved 4 April 2022.

Further reading

[edit]- Nigel Rees (2011). Don't You Know There's a War On?: Words and Phrases from the World Wars. Batsford. ISBN 978-1906388997.