Sofosbuvir

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Sovaldi, others[1] |

| Other names | PSI-7977; GS-7977 |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a614014 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth[3] |

| Drug class | HCV polymerase inhibitor |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 92% |

| Protein binding | 61–65% |

| Metabolism | Quickly activated to triphosphate (CatA/CES1, HIST1, phosphorylation) |

| Elimination half-life | 0.4 hrs (sofosbuvir) 27 hrs (inactive metabolite GS-331007) |

| Excretion | 80% urine, 14% feces (mostly as GS-331007) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.224.393 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C22H29FN3O9P |

| Molar mass | 529.458 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

Sofosbuvir, sold under the brand name Sovaldi among others, is a medication used to treat hepatitis C.[3] It is taken by mouth.[3][6]

Common side effects include fatigue, headache, nausea, and trouble sleeping.[3] Side effects are generally more common in interferon-containing regimens.[7]: 7 Sofosbuvir may reactivate hepatitis B in those who have been previously infected.[9] In combination with ledipasvir, daclatasvir or simeprevir, it is not recommended with amiodarone due to the risk of an abnormally slow heartbeat.[7] Sofosbuvir is in the nucleotide analog family of medications and works by blocking the hepatitis C NS5B protein.[6]

Sofosbuvir was discovered in 2007 and approved for medical use in the United States in 2013.[7][10][11] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[12][13]

Medical uses

[edit]

Initial HCV treatment

[edit]In 2016, the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Diseases Society of America jointly published a recommendation for the management of hepatitis C. In this recommendation, sofosbuvir used in combination with other drugs is part of all first-line treatments for HCV genotypes 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6, and is also part of some second-line treatments.[14] Sofosbuvir in combination with velpatasvir is recommended for all genotypes with a cure rate greater than 90%, and close to 100% in most cases. The duration of treatment is typically 12 weeks.[14][15]

Sofosbuvir is also used with other medications and longer treatment durations, depending on specific circumstances, genotype and cost-effectiveness–based perspective. For example, for the treatment of genotypes 1, 4, 5, and 6 hepatitis C infections, sofosbuvir can be used in combination with the viral NS5A inhibitor ledipasvir.[16] In genotype 2 and 3 HCV infections, sofosbuvir can be used in combination with daclatasvir. For the treatment of cases with cirrhosis or liver transplant patients, weight-based ribavirin is sometimes added. Peginterferon with or without sofosbuvir is not recommended in an initial HCV treatment.[14]

Compared to previous treatments, sofosbuvir-based regimens provide a higher cure rate, fewer side effects, and a two- to four-fold reduction in therapy duration.[17][18][19] Sofosbuvir allows most people to be treated successfully without the use of peginterferon, an injectable drug with severe side effects that is a key component of older drug combinations for the treatment of hepatitis C virus.[20][21]

Prior failed treatment

[edit]For people who have experienced treatment failure with some form of combination therapy for hepatitis C infection, one of the next possible steps would be retreatment with sofosbuvir and either ledipasvir or daclatasvir, with or without weight-based ribavirin. The genotype and particular combination therapy a person was on when the initial treatment failed are also taken into consideration when deciding which combination to use next. The duration of retreatment can range from 12 weeks to 24 weeks depending on several factors, including which medications are used for the retreatment, whether the person has liver cirrhosis or not, and whether the liver damage is classified as compensated cirrhosis or decompensated cirrhosis.[14]

Pregnancy and breastfeeding

[edit]No adequate human data are available to establish whether or not sofosbuvir poses a risk to pregnancy outcomes.[7] However, ribavirin, a medication that is often given together with sofosbuvir to treat hepatitis C, is assigned a Pregnancy Category X (contraindicated in pregnancy) by the FDA.[22] Pregnant women with hepatitis C who take ribavirin have shown some cases of birth defects and death in their fetus.[23] It is recommended that sofosbuvir/ribarivin combinations be avoided in pregnant females and their male sexual partners in order to reduce harmful fetal defects caused by ribavirin. Females who could potentially become pregnant should undergo a pregnancy test 2 months prior to starting the sofosbuvir/ribavirin/peginterferon combination treatment, monthly throughout the duration of the treatment, and six months post-treatment to reduce the risk of fetal harm in case of accidental pregnancy.[23]

It is unknown whether sofosbuvir and ribavirin pass into breastmilk; therefore, it is recommended that the mother does not breastfeed during treatment with sofosbuvir alone or in combination with ribavirin.[7][23]

Contraindications

[edit]There are no specific contraindications for sofosbuvir when used alone. However, when used in combination with ribavirin or peginterferon alfa/ribavirin, or others, the contraindications applicable to these agents are applied.[7]

Side effects

[edit]Sofosbuvir used alone and in combination with other drugs such as ribavirin with or without a peginterferon has a good safety profile. Common side effects are fatigue, headache, nausea, rash, irritability, dizziness, back pain, and anemia. Most side effects are more common in interferon-containing regimens as compared to interferon-free regimens. For example, fatigue and headache are nearly reduced by half, influenza-like symptoms are reduced to 3–6% as compared to 16–18%, and neutropenia is almost absent in interferon-free treatment.[7]: 7 [24]

Sofosbuvir may reactivate hepatitis B in those who have been previously infected.[9] The European Medicines Agency (EMA) has recommended screening all people for hepatitis B before starting sofosbuvir for hepatitis C in order to minimize the risk of hepatitis B reactivation.[25]

Interactions

[edit]Sofosbuvir (in combination with ledipasvir, daclatasvir or simeprevir) should not be used with amiodarone due to the risk of abnormally slow heartbeats.[7]

Sofosbuvir is a substrate of P-glycoprotein, a transporter protein that pumps drugs and other substances from intestinal epithelium cells back into the gut. Therefore, inducers of intestinal P-glycoprotein, such as rifampicin and St. John's wort, could reduce the absorption of sofosbuvir.[7]

In addition, coadministration of sofosbuvir with anticonvulsants (carbamazepine, phenytoin, phenobarbital, oxcarbazepine), antimycobacterials (rifampin, rifabutin, rifapentine), and the HIV protease inhibitor tipranavir and ritonavir is expected to decrease sofosbuvir concentration. Thus, coadministration is not recommended.[7]

The interaction between sofosbuvir and a number of other drugs, such as ciclosporin, darunavir/ritonavir, efavirenz, emtricitabine, methadone, raltegravir, rilpivirine, tacrolimus, or tenofovir disoproxil, were evaluated in clinical trials and no dose adjustment is needed for any of these drugs.[7][26]

Pharmacology

[edit]Mechanism of action

[edit]Sofosbuvir inhibits the hepatitis C NS5B protein.[6] Sofosbuvir appears to have a high barrier to the development of resistance.[27]

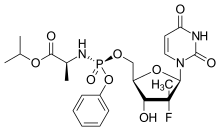

Sofosbuvir is a prodrug of the Protide type, whereby the active phosphorylated nucleotide is granted cell permeability and oral bioavailability. It is metabolized to the active antiviral agent GS-461203 (2'-deoxy-2'-α-fluoro-β-C-methyluridine-5'-triphosphate). GS-461203 serves as a defective substrate for the NS5B protein, which is the viral RNA polymerase, thus acts as an inhibitor of viral RNA synthesis.[28] Although sofosbuvir has a 3' hydroxyl group to act as a nucleophile for an incoming NTP, a similar nucleotide analogue, 2'-deoxy-2'-α-fluoro-β-C-methylcytidine, is proposed to act as a chain terminator because the 2' methyl group of the nucleotide analogue causes a steric clash with an incoming NTP.[29] Sofosbuvir may act in a similar way.[citation needed]

Pharmacokinetics

[edit]Sofosbuvir is only administered orally. The peak concentration after oral administration is 0.5–2 hours post-dose, regardless of initial dose.[30] Peak plasma concentration of the main circulating metabolite GS-331077 occurs 2–4 hours post-dose.[30] GS-331077 is the pharmacologically inactive nucleoside.[7]

Plasma protein binding of sofosbuvir is 61–65%, while GS-331077 has minimal binding.[7]

Sofosbuvir is activated in the liver to the triphosphate GS-461203 by hydrolysis of the carboxylate ester by either of the enzymes cathepsin A or carboxylesterase 1, followed by cleaving of the phosphoramidate by the enzyme histidine triad nucleotide-binding protein 1 (HINT1), and subsequent repeated phosphorylation.[31] Dephosphorylation creates the inactive metabolite GS-331077. The half life of sofosbuvir is 0.4 hours, and the half life of GS-331077 is 27 hours.[7]Following a single 400 mg oral dose of sofosbuvir, 80% is excreted in urine, 14% in feces, and 2.5% in expired air recovery. However, of the urine recovery 78% was the metabolite (GS-331077) and 3.5% was sofosbuvir.[30]

Chemistry

[edit]Prior to the discovery of sofosbuvir, a variety of nucleoside analogs had been examined as antihepatitis C treatments, but these exhibited relatively low potency. This low potency arose in part because the enzymatic addition of the first of the three phosphate groups of the triphosphate is slow. The design of sofosbuvir, based on the ProTide approach, avoids this slow step by building the first phosphate group into the structure of the drug during synthesis. Additional groups are attached to the phosphorus to temporarily mask the two negative charges of the phosphate group, thereby facilitating entry of the drug into the infected cell.[32] The NS5B protein is a RNA-dependent RNA polymerase critical for the viral reproduction cycle.[citation needed]

History

[edit]Sofosbuvir was discovered in 2007 by Michael J. Sofia, a scientist at Pharmasset, and the drug was first tested in people in 2010. In 2011, Gilead Sciences bought Pharmasset for about $11 billion.[11] Gilead submitted the New Drug Application for sofosbuvir in combination with ribavirin in April 2013, and in October 2013 it received the FDA's Breakthrough Therapy Designation.[33] In December 2013, the FDA approved sofosbuvir in combination with ribavirin for oral dual therapy of HCV genotypes 2 and 3, and for triple therapy with injected pegylated interferon (pegIFN) and RBV for treatment-naive people with HCV genotypes 1 and 4.[34][35] Two months before, the FDA had approved another drug, simeprevir, as a hepatitis C treatment.[34]

In 2014, the fixed dose combination drug sofosbuvir/ledipasvir, the latter a viral NS5A inhibitor, was approved; it had also been granted breakthrough status.[36]

Prior to the availability of sofosbuvir, hepatitis C treatments involved 6 to 12 months of treatment with an interferon-based regimen. This regimen provided cure rates of 70% or less and was associated with severe side effects, including anemia, depression, severe rash, nausea, diarrhea, and fatigue. As sofosbuvir clinical development progressed, physicians began to "warehouse" people in anticipation of its availability.[37] Sofosbuvir's U.S. launch was the fastest of any new drug in history.[38]

Society and culture

[edit]Sofosbuvir is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[12][13]

Economics

[edit]Following its approval by the FDA in 2013,[34] the price of sofosbuvir as quoted in various media sources in 2014 ranged from $84,000 to $168,000 depending on course of treatment in the U.S.[39] and £35,000 in the United Kingdom for a 12-week regimine,[40] causing considerable controversy.[41][42] Sofosbuvir was more affordable in Japan and South Korea at approximately $300 and $5900 respectively for a 12-week treatment, with each government covering 99% and 70% of the cost respectively.[43][44] In 2014, Gilead announced it would work with generic manufacturers in 91 developing countries to produce and sell sofosbuvir, and that it would sell a name brand version of the product in India for approximately $300 per course of treatment; it had signed agreements with generic manufacturers by September 2015.[45][46]

United States

[edit]Since its launch, the price of sofosbuvir declined as more competitors entered the direct-acting antiviral (DAA) market.[47] In 2020, the price for a course of sofosbuvir was $64,693 in the United States.[48] In 2014, the list price of a 12-week combination treatment with a sofosbuvir-based regimen ranged from US$84,000 to $94,000.[49][50][51] In April 2014, U.S. House Democrats Henry Waxman, Frank Pallone Jr., and Diana DeGette wrote Gilead Sciences Inc. questioning the $84,000 price for sofosbuvir. They specifically asked Gilead CEO John Martin to "explain how the drug was priced, what discounts are being made available to low-income patients and government health programs, and the potential impact to public health by insurers blocking or delaying access to the medicine because of its cost."[52] Sofosbuvir is cited as an example of how specialty drugs present both benefits and challenges.[52][53][54]

Sofosbuvir also is an excellent example of both the benefit and the challenge of specialty medications. On one hand, this agent offers up to a 95% response rate as part of an interferon-free treatment regimen for hepatitis C. Generally speaking, it is more effective and better tolerated than alternative treatments. Unfortunately, the current per pill cost—$1,000—results in an $84,000 treatment course, creating barriers to therapy for many. Patients, providers, and payors alike have expressed outrage, and the debate has even drawn the attention of the US Congress. Despite these concerns, sofosbuvir rapidly has become a top seller in the United States...[53]

In February 2015, Gilead announced that due in part to negotiated discounts with pharmacy benefit managers and legally mandated discounts to government payers, the average discount-to-list price in 2014 was 22%. The company estimated that the average discount in 2015 would be 46%.[55] According to the California Technology Assessment Forum, a panel of academic pharmacoeconomic experts, representatives of managed care organizations, and advocates for people with hepatitis, a 46% discount would bring the average price of treatment to about $40,000, at which price sofosbuvir-based treatment regimens represent a "high value" for people and healthcare systems.[56][57][58]

Because of sofosbuvir's high price in the United States, by 2017, some states—such as Louisiana—were withholding the medicine from Medicaid patients with hepatitis until their livers were severely damaged.[59] This puts "patients at increased risk of medical complications" and contributes to the "transmission of the hepatitis C virus".[60] In an article published in May 2016 in Health Affairs, the authors proposed the invocation of the federal "government patent use" law which would enable the government to procure "important patent-protected" drugs at lower prices while compensating "the patent-holding companies reasonable royalties ... for research and development."[60] By July 2017, Louisiana's health secretary Rebekah Gee, who described Louisiana as America's "public-health-crisis cradle", was investigating the use of the "government patent use" as a strategy.[59]

Japan and South Korea

[edit]Unlike other comparable Western developed countries, sofosbuvir is far more affordable in Japan and South Korea at approximately $300 and $2165 cost to patients respectively for a 12-week treatment, as each government covers 99% and 70% of the original cost respectively.[43][44][61]

Germany

[edit]In Germany, negotiations between Gilead and health insurers led to a price of €41,000 for 12 weeks of treatment. This is the same price previously negotiated with the national healthcare system in France, except that additional discounts and rebates apply in France depending on the volume of sales and the number of treatment failures.[62]

Switzerland

[edit]In Switzerland, the price is fixed by the government every three years. The price in 2016 was CHF 16,102.50 (about 1:1 to the US dollar) for 24 pills of 400 mg.[63]

United Kingdom

[edit]In 2020, the originator price per course of sofosbuvir was £35,443.[48] In 2013, the price in the United Kingdom was expected to be £35,000 for a 12-weeks course.[40] NHS England established 22 Operational Delivery Networks to roll out delivery, which was approved by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence in 2015, and proposes to fund 10,000 courses of treatment in 2016–17. Each was given a "run rate" of how many people they were allowed to treat, and this was the NHS's single biggest new treatment investment in 2016.[64]

Croatia

[edit]As of 2015, sofosbuvir is included on the list of essential medications in Croatia and its cost is fully covered by the Croatian Health Insurance Fund. As a result of negotiations with the manufacturer, only therapies with successful outcome would be paid by the Fund with the rest being covered by the manufacturer.[65]

India

[edit]In July 2014, Gilead Sciences filed a patent for sofosbuvir in India. If the office of the controller general of patents had granted it, Gilead would have obtained exclusive rights to produce and sell sofosbuvir in the country. However, in January 2015, the Indian Patent Office rejected Gilead's application. Gilead's lawyers moved the Delhi High Court against this decision. That decision was overturned on appeal in February 2015.[66][67] In the meantime, it[clarification needed] granted Indian companies voluntary licenses (VLs), which allowed them to make and sell in a selected few countries at a discounted price. This agreement also granted 7% of the royalties to Gilead. However, the list of countries open to Indian firms under this agreement excluded 73 million people with hepatitis C.[68]

Developing world

[edit]In 2014, Gilead announced it would seek generic licensing agreements with manufacturers to produce sofosbuvir in 91 developing countries, which contained 54% of the world's HCV-infected population. Gilead also said it would sell a name brand version of the product in India for $300 per course of treatment, approximately double a third party estimate of the minimum achievable cost of manufacture.[45] It had signed licenses with generic manufacturers by September 2015.[46] The leader of one Indian activist group called this move inadequate,[46] but nine companies launched products, which "unleashed a fierce marketing war", according to India's The Economic Times.[1]

In Egypt, which had the world's highest incidence of hepatitis C, Gilead offered sofosbuvir at the discounted price of $900 to the Egyptian government. The government in turn made it free to patients. Later, Gilead licensed a generic version to be available in Egypt.[69]

The Access to Medicine Index ranked Gilead first among the world's 20 largest pharmaceutical countries in the Pricing, Manufacturing and Distribution category in both 2013 and 2014, citing Gilead's "leading performance in equitable pricing."[70] In contrast, Jennifer Cohn of Doctors Without Borders and the organization Doctors of the World criticized the price of sofosbuvir as reflecting "corporate greed" and ignoring the needs of people in developing countries.[41][42]

In Algeria, as of 2011 about 70,000 people were infected with hepatitis C.[71] As of August 2015, Gilead had licensed its partners in India to sell sofosbuvir in Algeria.[72][73] It had been criticized for not making the drug available in middle-income countries including Algeria prior to that.[71][72][74]

Controversies

[edit]The price has generated considerable controversy.[41][42] In 2017, the range of costs per treatment varied from about $84,000[75] to about $50.[76]

Patent challenges

[edit]In February 2015, it was reported[77] that Doctors of the World had submitted an objection to Gilead's patent[78] at the European Patent Office, claiming that the structure of sofosbuvir is based on already known molecules.[79] In particular, Doctors of the World argued that the Protide technology powering sofosbuvir was previously invented by the Chris McGuigan team at Cardiff University in the UK, and that the Gilead drug is not therefore inventive.[80][81] The group filed challenges in other developing countries as well.[82] These challenges were unsuccessful.[83]

Medical tourism

[edit]Due to the high cost of sofosbuvir in the U.S., as of 2016 increasing numbers of Americans with hepatitis C were traveling to India to purchase the drug. Similarly, increasing numbers of Chinese were also traveling to India to purchase sofosbuvir, which had not yet been approved for sale in China by the country's State Food and Drug Administration (SFDA).[84]

Research

[edit]Combinations of sofosbuvir with NS5A inhibitors, such as daclatasvir, ledipasvir or velpatasvir, have shown sustained virological response rates of up to 100% in people infected with HCV. Most studies indicate that the efficacy rate is between 94% and 97%; much higher than previous treatment options.[85][86][87] That treatments could be conducted at very low costs was demonstrated by Hill and coworkers who presented data on 1,160 patients who used generic versions of solfosbuvir, ledipasvir, plus daclatasvir from suppliers in India, Egypt, China and other countries and reported over 90% success at costs of about $50 per therapy.[76]

Sofosbuvir has also been tested against other viruses such as the Zika virus[88] and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2).[89]

DIY Home Synthesis

[edit]At DEF CON 32, Mixæl Swan Laufer, a representative of the Four Thieves Vinegar Collective, presented a talk titled "Eradicating Hepatitis C with BioTerrorism." The presentation argued that advancements in open-source tools and chemistry enable individuals to synthesize certain medications, such as Sovaldi, at home, potentially bypassing high pharmaceutical costs.

During the talk, Laufer demonstrated tools and techniques used by the collective to synthesize pharmaceuticals, showcasing examples of the medications created. To illustrate the efficacy and accessibility of the process, he consumed a dose of Sovaldi onstage, despite not having Hepatitis C, as a symbolic gesture of the drug's claimed safety.[90][91]

See also

[edit]- AT-527—a similar drug developed for the treatment of SARS-CoV-2

- Tenofovir alafenamide—a nucleotide reverse-transcriptase inhibitor that uses similar phosphoramidate prodrug technology[92][32]

- Remdesivir—a nucleotide analogue RNA polymerase inhibitor originally intended to treat hepatitis C that uses similar phosphoramidate prodrug technology and displays very similar PK.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Divya Rajagopal for the Economic Times. Sept 12, 2015. Can Indian generic makers find gold with a blockbuster Hepatitis C drug?

- ^ "Sofosbuvir (Sovaldi) Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. 16 December 2019. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

- ^ a b c d "Sofosbuvir". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 1 December 2016. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- ^ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ "Prescription medicines: registration of new chemical entities in Australia, 2014". Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). 21 June 2022. Retrieved 10 April 2023.

- ^ a b c d "Sovaldi 400 mg film coated tablets - Summary of Product Characteristics". UK Electronic Medicines Compendium. September 2016. Archived from the original on 10 November 2016. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "Sovaldi- sofosbuvir tablet, film coated Sovaldi- sofosbuvir pellet". DailyMed. 27 September 2019. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- ^ "Sovaldi Access- sofosbuvir tablet, film coated". DailyMed. Retrieved 26 January 2022.

- ^ a b "Direct-Acting Antivirals for Hepatitis C: Drug Safety Communication - Risk of Hepatitis B Reactivating". FDA. 4 October 2016. Archived from the original on 6 October 2016. Retrieved 6 October 2016.

- ^ "Sofosbuvir (Sovaldi) - Treatment - Hepatitis C Online". www.hepatitisc.uw.edu. Archived from the original on 23 December 2016. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- ^ a b Gounder C (9 December 2013). "A Better Treatment for Hepatitis C". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 20 September 2016.

- ^ a b World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ^ a b World Health Organization (2021). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 22nd list (2021). Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/345533. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2021.02.

- ^ a b c d "Recommendations for Testing, Managing, and Treating Hepatitis C" (PDF). AASLD/IDSA. 27 September 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 November 2016. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- ^ "EPCLUSA (sofosbuvir and velpatasvir) Prescribing information" (PDF). Gilead Sciences, Inc. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 June 2017. Retrieved 16 June 2017.

- ^ "Harvoni- ledipasvir and sofosbuvir tablet, film coated Harvoni- ledipasvir and sofosbuvir tablet, film coated Harvoni- ledipasvir and sofosbuvir pellet". DailyMed. Retrieved 26 January 2022.

- ^ Berden FA, Kievit W, Baak LC, Bakker CM, Beuers U, Boucher CA, et al. (October 2014). "Dutch guidance for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C virus infection in a new therapeutic era". The Netherlands Journal of Medicine. 72 (8): 388–400. PMID 25387551.

- ^ Cholongitas E, Papatheodoridis GV (2014). "Sofosbuvir: a novel oral agent for chronic hepatitis C". Annals of Gastroenterology. 27 (4): 331–337. PMC 4188929. PMID 25332066.

- ^ Tran TT (December 2012). "A review of standard and newer treatment strategies in hepatitis C". The American Journal of Managed Care. 18 (14 Suppl): S340 – S349. PMID 23327540.

- ^ Yau AH, Yoshida EM (September 2014). "Hepatitis C drugs: the end of the pegylated interferon era and the emergence of all-oral interferon-free antiviral regimens: a concise review". Canadian Journal of Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 28 (8): 445–451. doi:10.1155/2014/549624. PMC 4210236. PMID 25229466.

- ^ Calvaruso V, Mazza M, Almasio PL (May 2011). "Pegylated-interferon-α(2a) in clinical practice: how to manage patients suffering from side effects". Expert Opinion on Drug Safety. 10 (3): 429–435. doi:10.1517/14740338.2011.559161. hdl:10447/73456. PMID 21323500. S2CID 207487328.

- ^ "Ribavirin Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. 21 August 2019. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- ^ a b c "Rebetol- ribavirin capsule Rebetol- ribavirin liquid". DailyMed. Retrieved 26 January 2022.

- ^ Bhatia HK, Singh H, Grewal N, Natt NK (October 2014). "Sofosbuvir: A novel treatment option for chronic hepatitis C infection". Journal of Pharmacology & Pharmacotherapeutics. 5 (4): 278–284. doi:10.4103/0976-500X.142464. PMC 4231565. PMID 25422576.

- ^ "Direct-acting antivirals indicated for treatment of hepatitis C (interferon-free)". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 17 September 2018. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- ^ Karageorgopoulos DE, El-Sherif O, Bhagani S, Khoo SH (February 2014). "Drug interactions between antiretrovirals and new or emerging direct-acting antivirals in HIV/hepatitis C virus coinfection". Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases. 27 (1): 36–45. doi:10.1097/QCO.0000000000000034. PMID 24305043. S2CID 24286602.

- ^ Pol S, Corouge M, Vallet-Pichard A (March 2016). "Daclatasvir-sofosbuvir combination therapy with or without ribavirin for hepatitis C virus infection: from the clinical trials to real life". Hepatic Medicine: Evidence and Research. 8: 21–26. doi:10.2147/HMER.S62014. PMC 4786064. PMID 27019602.

- ^ Fung A, Jin Z, Dyatkina N, Wang G, Beigelman L, Deval J (July 2014). "Efficiency of incorporation and chain termination determines the inhibition potency of 2'-modified nucleotide analogs against hepatitis C virus polymerase". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 58 (7): 3636–3645. doi:10.1128/AAC.02666-14. PMC 4068585. PMID 24733478.

- ^ Ma H, Jiang WR, Robledo N, Leveque V, Ali S, Lara-Jaime T, et al. (October 2007). "Characterization of the metabolic activation of hepatitis C virus nucleoside inhibitor beta-D-2'-Deoxy-2'-fluoro-2'-C-methylcytidine (PSI-6130) and identification of a novel active 5'-triphosphate species". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 282 (41): 29812–29820. doi:10.1074/jbc.M705274200. PMID 17698842.

- ^ a b c Kirby BJ, Symonds WT, Kearney BP, Mathias AA (July 2015). "Pharmacokinetic, Pharmacodynamic, and Drug-Interaction Profile of the Hepatitis C Virus NS5B Polymerase Inhibitor Sofosbuvir". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 54 (7): 677–690. doi:10.1007/s40262-015-0261-7. PMID 25822283. S2CID 20488837.

- ^ Dinnendahl V, Fricke U, eds. (2015). Arzneistoff-Profile (in German). Vol. 9 (28 ed.). Eschborn, Germany: Govi Pharmazeutischer Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7741-9846-3.

- ^ a b Murakami E, Tolstykh T, Bao H, Niu C, Steuer HM, Bao D, et al. (November 2010). "Mechanism of activation of PSI-7851 and its diastereoisomer PSI-7977". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 285 (45): 34337–34347. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.161802. PMC 2966047. PMID 20801890.

- ^ "Application Number: 204671Orig1s000: Medical Reviews" (PDF). FDA. 20 November 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 November 2016.

- ^ a b c "FDA approves Sovaldi for chronic hepatitis C". FDA New Release. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 6 December 2013. Archived from the original on 9 December 2013.

- ^ Tucker M (6 December 2013). "FDA Approves 'Game Changer' Hepatitis C Drug Sofosbuvir". Medscape. Archived from the original on 17 May 2015.

- ^ "FDA approves first combination pill to treat hepatitis C". Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 4 May 2015.

- ^ Loftus P (5 March 2013). "Hepatitis C Dilemma: Treat Illness With Interferon Now or Wait? - WSJ". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 2 June 2017.

- ^ Herper M (21 February 2014). "Gilead's Hepatitis C Pill Takes Off Like A Rocket". Forbes. Archived from the original on 31 August 2017.

- ^ Harris G (15 September 2014). "Maker of Costly Hepatitis C Drug Sovaldi Strikes Deal on Generics for Poor Countries". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 31 January 2017.

- ^ a b Boseley S (15 January 2015). "Hepatitis C drug delayed by NHS due to high cost". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 10 November 2016.

- ^ a b c Stanton T (9 December 2013). "Activists pounce on $1,000-a-day price for Gilead's hep C wonder drug, Sovaldi". FiercePharma. Archived from the original on 18 February 2014. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ^ a b c Waldman R. "Gilead's HCV drug sofosbuvir approved by the FDA but accessible for how many?" (PDF). Doctors of the World. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 February 2014. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ^ a b "C형간염 치료제 건강보험 적용". 20 April 2016. Archived from the original on 30 May 2016. Retrieved 2 August 2016.

- ^ a b "C형 간염 치료제 신약, 내달 1일부터 건강보험 적용" [New hepatitis C treatment to be covered by health insurance from the 1st of next month] (in Korean). 20 April 2016. Archived from the original on 31 May 2016. Retrieved 2 August 2016.

- ^ a b van de Ven N, Fortunak J, Simmons B, Ford N, Cooke GS, Khoo S, Hill A (April 2015). "Minimum target prices for production of direct-acting antivirals and associated diagnostics to combat hepatitis C virus". Hepatology. 61 (4): 1174–1182. doi:10.1002/hep.27641. PMC 4403972. PMID 25482139.

- ^ a b c Kalra A, Siddiqui Z (15 September 2014). "Gilead licenses hepatitis C drug to Cipla, Ranbaxy, five others". Reuters India. Archived from the original on 10 December 2014.

- ^ "Analysis of prescription drugs for the treatment of hepatitis C in the United States". www.milliman.com. Retrieved 4 February 2022.

- ^ a b Barber MJ, Gotham D, Khwairakpam G, Hill A (September 2020). "Price of a hepatitis C cure: Cost of production and current prices for direct-acting antivirals in 50 countries". Journal of Virus Eradication. 6 (3): 100001. doi:10.1016/j.jve.2020.06.001. PMC 7646676. PMID 33251019.

- ^ Pollack A (10 October 2014). "Harvoni, a Hepatitis C Drug from Gilead, Wins F.D.A. Approval". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 26 January 2017.

- ^ "Gilead Faces Lawsuit Over Hepatitis C Drug Pricing". Drug Discovery & Development. Advantage Business Media. Associated Press. 11 December 2014. Archived from the original on 13 December 2014.

- ^ Pollack A (6 December 2013). "F. D. A. Approves Pill to Treat Hepatitis". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 3 February 2017.

- ^ a b Armstrong D (21 March 2014). "Gilead's $84,000 Treatment Questioned by U.S. Lawmakers". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- ^ a b Lucio S (February 2015). "The Increasing Impact of High-Cost Specialty Therapies". Pharmacy Purchasing & Products. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 4 December 2015.

- ^ Brennan T, Shrank W (August 2014). "New expensive treatments for hepatitis C infection". JAMA. 312 (6): 593–594. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.8897. PMID 25038617.

- ^ "Gilead Q4 2014 Earnings Call". 3 February 2015. Archived from the original on 22 February 2015.

- ^ "New Lower Prices for Gilead Hepatitis C Drugs Reach CTAF Threshold for High Health System Value" (Press release). 17 February 2015. Archived from the original on 22 February 2015. Retrieved 22 February 2015.

- ^ California Technology Assessment Forum (10 March 2014). "Treatments for Hepatitis C". Archived from the original on 20 October 2014.

- ^ "Medical Groups Question Price of New Hep C Drug". The New York Times. Associated Press. 11 March 2014.

- ^ a b Johnson CY (3 July 2017). "Louisiana considers radical step to counter high drug prices: Federal intervention". Baton Rouge, Louisiana. Archived from the original on 23 September 2017. Retrieved 4 July 2017.

- ^ a b Kapczynski A, Kesselheim AS (May 2016). "'Government Patent Use': A Legal Approach To Reducing Drug Spending" (PDF). Health Affairs. 35 (5): 791–797. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1120. PMID 27140984. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 September 2017. Retrieved 4 June 2017.

- ^ "Medi:gate News 6월 1일부터 하보니·소발디 가격 절반된다…하보니 급여도 확대" [From the 1st of the month, the price of Harboni and Sovaldi will be halved… Harboni salary increase] (in Korean).

- ^ "Gilead strikes Sovaldi price deal in Germany as it picks up speed in EU". 13 February 2015. Archived from the original on 19 February 2015.

- ^ "Sovaldi / Sofosbuvir medication in Switzerland". Archived from the original on 4 October 2016.

- ^ "NHS England rollout of ground-breaking drugs 'changes role of NICE'". Health Service Journal. 4 April 2016. Archived from the original on 5 June 2016. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- ^ "Tri skupa lijeka za hepatitis C od danas na besplatnoj listi HZZO-a".

- ^ Mezher M (4 February 2015). "Follow the Rules, Indian Court Tells Patent Office in Sovaldi Case". Regulatory Affairs Professionals Society. Archived from the original on 1 May 2016.

- ^ Datta J (2 February 2015). "More patent-opposition on Gilead's hepatitis C drug, sofosbuvir". Hindu Business Line. Archived from the original on 23 September 2017.

- ^ Krishnan V, Gahlot M. "How big pharma and the Indian government are letting millions of patients down". The Caravan. Retrieved 25 July 2019.

- ^ "Curing Hepatitis C, in an Experiment the Size of Egypt". New York Times. 15 December 2015.

- ^ "Pricing, Manufacturing & Distribution | Access to Medicine Index 2014". Archived from the original on 6 February 2015.

- ^ a b "Hepatitis C and Drug Pricing: The Need for a Better Balance" (PDF). mfAR, The Foundation for AIDS Research. February 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 April 2016. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- ^ a b "An Alternative Research and Development Strategy to Deliver Affordable Treatments for Hepatitis C Patients" (PDF). Drugs for Neglected Diseases Initiative. April 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 August 2016.

- ^ "Chronic Hepatitis C Treatment Expansion Generic Manufacturing for Developing Countries" (PDF). Gilead. August 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 March 2016.

- ^ "Strategies to Secure Access to Generic Hepatitis C Medicines" (PDF). Doctors without Borders. May 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 January 2017.

- ^ Hill A, Simmons B, Gotham D, Fortunak J (January 2016). "Rapid reductions in prices for generic sofosbuvir and daclatasvir to treat hepatitis C". Journal of Virus Eradication. 2 (1): 28–31. doi:10.1016/S2055-6640(20)30691-9. PMC 4946692. PMID 27482432.

- ^ a b Merlot J (2 November 2017). "Hepatitis C könnte für 50 Dollar geheilt werden". Der Spiegel (in German). Retrieved 2 November 2017.

- ^ "Doctors of the World—Médecins Du Monde opposes sofosbuvir patent in Europe". Médecins du Monde. Archived from the original on 12 February 2015. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- ^ "European Patent EP2203462, granted 21 May 2014". European Patent Register. European Patent Office. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- ^ Kuhrt N (10 February 2015). "Hepatitis-Pille Sovaldi: "Ärzte der Welt" geht gegen Patent vor" [Hepatitis pill Sovaldi: "Doctors of the World" takes action against the patent]. Der Spiegel (in German). Archived from the original on 10 February 2015. Retrieved 10 February 2015.

- ^ "Conflit autour d'un traitement contre l'hépatite C". Le Monde.fr (in French). 10 February 2015. Retrieved 4 March 2015.

- ^ "Charity challenges Gilead's European patent on hepatitis C therapy Sovaldi". 10 February 2015. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 4 March 2015.

- ^ Pollack A (20 May 2015). "High Cost of Sovaldi Hepatitis C Drug Prompts a Call to Void Its Patents". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 23 May 2015.

- ^ "European Patent Office maintain patent on hepatitis C drug sofosbuvir". www.doctorsoftheworld.org.uk. 14 September 2018. Retrieved 30 November 2024.

- ^ "More Americans and Chinese Traveling to India for Hepatitis C Treatment". WebMD China. 3 June 2016. Archived from the original on 30 August 2018. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- ^ Childs-Kean LM, Hand EO (February 2015). "Simeprevir and sofosbuvir for treatment of chronic hepatitis C infection". Clinical Therapeutics. 37 (2): 243–267. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2014.12.012. PMID 25601269.

- ^ Smith MA, Chan J, Mohammad RA (March 2015). "Ledipasvir-sofosbuvir: interferon-/ribavirin-free regimen for chronic hepatitis C virus infection". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 49 (3): 343–350. doi:10.1177/1060028014563952. PMID 25515863. S2CID 20944806.

- ^ "FDA approves Epclusa for treatment of chronic Hepatitis C virus infection". News Release. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 28 June 2016. Archived from the original on 3 June 2017.

- ^ Sacramento CQ, de Melo GR, de Freitas CS, Rocha N, Hoelz LV, Miranda M, et al. (January 2017). "The clinically approved antiviral drug sofosbuvir inhibits Zika virus replication". Scientific Reports. 7 (1): 40920. Bibcode:2017NatSR...740920S. doi:10.1038/srep40920. PMC 5241873. PMID 28098253.

- ^ Mesci P, de Souza JS, Martin-Sancho L, Macia A, Saleh A, Yin X, et al. (November 2022). "SARS-CoV-2 infects human brain organoids causing cell death and loss of synapses that can be rescued by treatment with Sofosbuvir". PLOS Biology. 20 (11): e3001845. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.3001845. PMC 9632769. PMID 36327326.

- ^ "DEF CON 32 - Eradicating Hepatitis C with BioTerrorism - Mixæl Swan Laufer". DEFCON Youtube Channel.

- ^ Koebler J (4 September 2024). "'Right to Repair for Your Body': The Rise of DIY, Pirated Medicine". 404 Media. Retrieved 30 December 2024.

- ^ "Comparison of tenofovir prodrugs: TAF vs TDF". DRUG R&D INSIGHT. 24 January 2015. Archived from the original on 25 November 2015. Retrieved 24 November 2015.

Further reading

[edit]- Dean L (2017). "Sofosbuvir Therapy and IFNL4 Genotype". In Pratt VM, McLeod HL, Rubinstein WS, et al. (eds.). Medical Genetics Summaries. National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). PMID 28520377. Bookshelf ID: NBK409960.

External links

[edit]- "Sofosbuvir". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.