Seraphim of Sarov

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

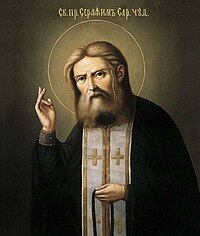

Seraphim of Sarov | |

|---|---|

Russian icon of Saint Seraphim of Sarov | |

| Confessor and Wonderworker | |

| Born | 30 July 1754 Kursk, Russian Empire |

| Died | 2 January 1833 (aged 78) Sarov, Russian Empire |

| Venerated in | Eastern Orthodox Church Anglican Communion |

| Canonized | 19 July 1903 (O.S.), Sarov Monastery by Holy Governing Synod |

| Major shrine | Diveevo Convent, Russia |

| Feast | 2 January, 19 July (opening of relics) |

| Attributes | Wearing peasant clothing, often kneeling with his hands upraised in prayer; crucifix worn about his neck; hands crossed over chest |

Seraphim of Sarov (Russian: Серафим Саровский; 30 July [O.S. 19 July] 1754 or 1759 – 14 January [O.S. 2 January] 1833), born Prókhor Isídorovich Moshnín (Mashnín) [Про́хор Иси́дорович Мошни́н (Машни́н)], is one of the most renowned Russian saints and is venerated in the Eastern Orthodox Church[1] and the Anglican Communion.[2] He is generally considered the greatest of the 18th-century startsy (elders). Seraphim extended the monastic teachings of contemplation, theoria and self-denial to the layperson. He taught that the purpose of the Christian life was to receive the Holy Spirit. Perhaps his most popular quotation amongst his devotees is "Acquire the Spirit of Peace, and thousands around you will be saved."

Seraphim was glorified by the Russian Orthodox Church in 1903.

Life

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2019) |

Born 19 July (O.S.) 1754, Seraphim was baptized with the name of Prochor, after Prochorus, one of the first Seven Deacons of the Early Church and the disciple of John the Evangelist. His parents, Isidore and Agathia Moshnin, lived in Kursk, Russia. His father was a merchant. He took part in the building of the Sergievsko-Kazansky Cathedral in Kursk, but died before its completion. His mother would take young Prochor to visit the church while under construction. On one occasion, the seven-year-old accidentally fell from the bell tower.[1] According to Eastern Orthodox Church tradition, a wonderworking icon of the Theotokos (Virgin Mary), Our Lady of Kursk, protected the young boy.

In 1775, at the age of 17, he visited Dorothea of Kiev. In 1777, at the age of 19, he joined the Sarov monastery as a novice (poslushnik). He was officially tonsured (took his monastic vows) in 1786 and given the religious name of Seraphim (which refers to Seraph-angels in the Bible). Shortly afterwards, he was ordained a hierodeacon (monastic deacon). In 1793, he was ordained as a hieromonk (monastic priest)[3] and became the spiritual leader of the Diveyevo Convent, which has since come to be known as the Seraphim-Diveyevo Convent.

Soon after this, Seraphim retreated to a log cabin in the woods outside Sarov monastery and led a solitary lifestyle as a hermit for 25 years. During this time his feet became swollen to the point that he had trouble walking. Sarov's eating and fasting habits became more strict. At first he ate bread obtained from the monastery and vegetables from his garden, then only vegetables. For three years, he ate only grass.[3]

One day, while chopping wood, Seraphim was attacked by a gang of thieves who beat him mercilessly with the handle of his own axe. He never resisted, and was left for dead. The robbers never found the money they sought, only an icon of the Theotokos (Virgin Mary) in his hut. Seraphim had a hunched back for the rest of his life. However, at the thieves' trial he pleaded to the judge for mercy on their behalf. He spent five months in the monastery, recovering from his injuries and then returned to the wilderness.[3]

After this incident Seraphim spent 1,000 successive nights on a rock in continuous prayer with his arms raised to the sky, a feat of asceticism deemed miraculous by the Eastern Orthodox Church, especially considering the pain from his injuries.

In 1815, in obedience to a reputed spiritual experience that he attributed to the Virgin Mary, Seraphim began admitting pilgrims to his hermitage as a confessor. He soon became immensely popular due to his reputation for healing powers and gift of prophecy. Hundreds of pilgrims per day visited him, drawn as well by his ability to answer his guests' questions before they could ask.

As extraordinarily harsh as Seraphim often was to himself, he was kind and gentle toward others – always greeting his guests with a prostration, a kiss, and exclaiming "Christ is risen!", and calling everyone "My joy". He died while kneeling before a tenderness icon of the Theotokos which he called "Joy of all Joys". This icon is kept currently in the chapel of the residence of the Patriarch of Moscow.

Relics, canonization and veneration

[edit]

There was a widespread popular belief in Russia that a saint's remains were supposed to be incorrupt, which was not the case with Seraphim as was officially ascertained by a commission that researched his grave in January 1903. This, however, did not deter canonisation, spearheaded by archimandrite Seraphim Chichagov as well as popular veneration.[a] At the end of January (O.S.) 1903, the Most Holy Synod, having received approval from Emperor Nicholas II, announced Seraphim's forthcoming glorification.[5] In early July 1903, his relics were transferred from their original burial place to the church of Saints Zosimus and Sabbatius. Nicholas II and Tsarina Alexandra provided a new cypress coffin to receive the relics. The solemn canonisation (discovery of the relics) festivities took place in Sarov on 19 July (1 August) 1903 and were attended by the Tsar, his wife, his mother Empress Maria Feodorovna, his sister-in-law Grand Duchess Elizabeth Feodorovna and other senior members of the Imperial Family.[6][7]

On 18 July 1903, Metropolitan Anthony Vadkovsky of St. Petersburg officiated at the Last Pannikhida (Memorial Service) in the Dormition Cathedral at Sarov, with the royal family in attendance. These would be the last prayers offered for Seraphim as a departed servant of God; from that time forward, prayers would instead be addressed to him as a saint. On 19 July, Seraphim's birthday, the late liturgy began at 8:00.[clarification needed] At the Little Entrance, twelve archimandrites lifted the coffin from the middle of the church and carried it around the holy table (altar), then placed it into a special shrine which had been constructed for it.

The festivities at Sarov ended with the consecration of the first two churches dedicated to Saint Seraphim. The first had been constructed over his monastic cell in the wilderness of Sarov. The second church was consecrated on 22 July at the Diveyevo convent.

Following the Bolshevik Revolution, Soviet authorities severely persecuted religious groups. As part of their persecution of Christians, they confiscated many relics of saints, including Seraphim. Furthermore, his biographer Seraphim Chichagov, who came to become a metropolitan, was arrested, sentenced to death and executed by firing squad in 1937 (and is also celebrated as a Russian Orthodox saint).

In 1991, Seraphim's relics were rediscovered after being hidden in a Soviet anti-religious museum for seventy years. This caused a sensation in post-Soviet Russia and throughout the Orthodox world. A crucession (religious procession) escorted the relics, on foot, all the way from Moscow to Diveyevo Convent, where they remain to this day.

On 19 October 2016, some relics of Seraphim were launched into space aboard the Soyuz MS-02.[8]

Seraphim is remembered in the Anglican Communion with a commemoration on 2 January.[9][failed verification][10]

In his book, Crossing the Threshold of Hope, Pope John Paul II referred to Seraphim of Sarov as a saint.[11]

On 15 September 2016, Metropolitan Hilarion of Volokolamsk, head of the Department for External Church Relations of the Moscow Patriarchate, presented to Pope Francis a relic of Seraphim from Patriarch Kirill of Moscow.[12] The Pope keeps the relic by his bedside and venerates it daily with a prayer for unity.[13]

Quotes

[edit]"Acquire a peaceful spirit, and around you thousands will be saved." "It is necessary that the Holy Spirit enter our heart. Everything good that we do, that we do for Christ, is given to us by the Holy Spirit, but prayer most of all, which is always available to us."[citation needed]

Seraphim and Old Believers

[edit]

The available information about relations between Seraphim of Sarov and Russian Old Believers tradition is somewhat contradictory. On the one hand, in all the memoirs and biographies, and in the collections of his sayings, he is undoubtedly portrayed as a convinced supporter of the reforms in the church and the official hierarchy.[14][better source needed] On the other hand, on icons of Seraphim he is usually depicted with a lestovka in his left hand,[15] and in some cases even in old Russian, Old-Believers-style monastic garments (with a peculiar klobuk, and an old-fashioned cast bronze cross), as it is with these objects that he is depicted on the only lifetime portrait of him.[16][unreliable source] The lestovka used by St.Seraphim is preserved up to this time among his personal belongings.[17][better source needed]

According to some sources, the known problems with the beatification of Seraphim of Sarov did happen exactly due to his general support and sympathy towards the Old Believers tradition,[18][19] in which case the negative assessment of the old rite, ascribed to him, would have been interpreted as inventions of his followers, who tried to put their teacher in the most favorable light in the eyes of the official church functionaries.[20] It was also suggested that Seraphim could have descended from a family of Old Ritualists,[18] or from a family of secret, cryptic Old Believers (that were widespread in northern and eastern areas of Russia),[16][unreliable source] possibly with consequent gradual shift towards edinoverie.[17]

In spite of some (alleged) controversy, Seraphim was known, at least at the level of official hagiography, for his rejection of the Russian old rites.[21] The majority of old believers authors doubt virtually all the facts known about Seraphim, as well as the very legitimacy of his beatification,[22][23] and his name is often used in interdenominational polemics.[16][unreliable source]

Notes

[edit]- ^ A manual for Russian clergy published in Kiev in 1913 had a special detailed explanation for this case that stressed that incorruptibility of a saint′s remains was not a sine qua non:

″Некоторые утверждают, будто мощи святых всегда и непременно суть совершенно нетленные, то есть совершенно целые, нисколько неразрушенные и неповрежденные тела. Но понимание слова „мощи“ непременно в смысле целого тела, а не частей его и преимущественно костей, – неправильно, и вводит в разногласие с греческой церковию, так как у греков вовсе не проповедуется учения, что мощи означают целое тело, и мощи наибольшей части святых в Греции и на Востоке (равно как и на Западе) суть кости. Самое нетление мощей всецерковным сознанием не считается общим непременным признаком для прославления святых угодников. История прославления святых показывает, что некоторые из чтимых нами святых были прославлены до открытия их мощей, некоторые прославлены спустя то или другое время и даже очень значительное время после открытия их мощей; мощи довольно многих прославленных святых никогда не были открываемы. Мощи многих святых и в настоящее время находятся под спудом: в большей части случаев это значит, что мощи совсем не были открываемы, в меньшей части значит, что были открываемы, но потом опять закрыты. Мощи святых, когда они нетленны, составляют чудо, но лишь дополнительное к тем чудесам, которые творятся чрез их посредство. Доказательство святости святых составляют те чудеса, которые творятся при их гробах, или от их мощей, а мощи, целые тела или только кости, суть дарованные нам, для поддержания в нас живейшего памятования о небесных молитвенниках за нас, священные и святые останки некоторых святых, которых мы должны чтить, как таковые, и суть те земные посредства, чрез которые Господь наиболее прославляет Свою чудодейственную силу.″

(С. В. Булгаков). [4]tr. "Some argue that the relics of the saints are always and certainly completely incorruptible, that is, completely whole, not at all undisturbed and undamaged bodies. But the understanding of the word "power" is certainly in the sense of the whole body, and not of its parts and mainly of the bones, is wrong, and introduces it into disagreement with the Greek Church, since the Greeks do not preach the doctrine at all that relics mean the whole body, and the power of the largest part the saints in Greece and in the East (as well as in the West) are bones. The very incorruption of relics by the all-church consciousness is not considered a common indispensable sign for the glorification of saints. The history of the glorification of the saints shows that some of the saints we venerate were glorified before the discovery of their relics, some were glorified after one time or another and even a very significant time after the discovery of their relics; the relics of quite a few illustrious saints have never been revealed. The relics of many saints are still under wraps: in most cases this means that the relics were not opened at all, in a smaller part it means that they were opened, but then closed again. The relics of the saints, when they are incorruptible, constitute a miracle, but only in addition to those miracles that are performed through them. Proof of the holiness of the saints are the miracles that are performed at their tombs, or from their relics, and relics, whole bodies or only bones, are those given to us, to maintain in us the most vivid remembrance of heavenly prayer books for us, the sacred and holy remains of some saints, which we must honor, as such, and are those earthly means through which the Lord most glorifies His miraculous power."

See also

[edit]- Hesychasm

- Diveevo convent

- Saint Seraphim of Sarov Church, Turnaevo

- Serafimovskoe Cemetery

- Thaumaturgy

- Tabor light

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Repose of Venerable Seraphim, Wonderworker of Sarov".

- ^ "The Calendar". The Church of England. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ a b c Johnston, William M. (4 December 2013). Encyclopedia of Monasticism. Routledge. p. 1146. ISBN 978-1-136-78716-4. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- ^ Настольная книга для священно-церковно-служителей (tr. "Handbook for clergymen"). Kiev, 1913, р. 272 (footnote).)

- ^ "Деяние Святейшаго Синода 29 января 1903 г. о канонизации преподобного Серафима Саровского" [Deed of the Holy Synod on January 29, 1903 on the canonization of the Monk Seraphim of Sarov]. www.pravoslavie.ru. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- ^ "Саровские торжества 1903 года" [Sarov celebrations of 1903]. www.ippo.ru. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- ^ "1 августа – обретение мощей преподобного Серафима, Саровского чудотворца / Статьи / Патриархия.ru" [August 1 – uncovering of the relics of St. Seraphim, the miracle worker of Sarov / Articles / Patriarchy.ru]. Патриархия.ru. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- ^ "Soyuz MS-02 spacecraft docking the International Space Station". Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- ^ "The Calendar". The Church of England. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ "For All the Saints / For All the Saints – A Resource for the Commemorations of the Calendar / Worship Resources/ Karakia/ ANZPB-HKMOA / Resources / Home – Anglican Church in Aotearoa, New Zealand and Polynesia". www.anglican.org.nz. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ Pope John Paul II (1994). Crossing the Threshold of Hope. Internet Archive. New York: Knopf. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-679-44058-1.

- ^ "Metropolitan Hilarion of Volokolamsk meets with Pope Francis of Rome". Russian Orthodox Church Department for External Church Relations. Retrieved 3 January 2025.

- ^ "Address of His Holiness Pope Francis to the Delegation of the Orthodox Patriarchate of Moscow". The Holy See. Retrieved 4 January 2025.

- ^ "Преподобный Серафим Саровский и старообрядцы"[permanent dead link] (tr. "Venerable Seraphim of Sarov and the Old Believers") – an article at serafimushka.ru

- ^ Iconography of St. Seraphim of Sarov at diveevo.ru (in Russian)

- ^ a b c Discussion at a religious history forum Archived 8 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine kuraev.ru

- ^ a b Сергей Чесноков. От отступничества к единоверию ("Sergey Chesnokov. From apostasy to common faith") Archived 13 January 2013 at archive.today

- ^ a b Кутузов Б.П. Церковная «реформа» ("Kutuzov B.P. Church "reform"") XVII века. М., 2003.

- ^ В.А. Степашкин. Преподобный Серафим Саровский: предания и факты ("V.A. Stepashkin. Venerable Seraphim of Sarov: legends and facts")

- ^ Преподобный старообрядец Серафим Саровский (tr. "Venerable Old Believer Seraphim of Sarov") – a chapter from a book of В.В. Смирнов "Падение III Рима"

- ^ Православные святые об еретичестве старообрядцев (tr. "Orthodox saints about the hereticism of the Old Believers") – in a journal "Меч и трость. Православный монархический журнал" ("Sword and cane. Orthodox monarchist magazine")

- ^ Никонианское «старчество» (tr. Nikonian "old age") – Андрей Езеров, as published atstaropomor.ru

- ^ В отсутствие святых (tr. "In the absence of the saints")] – Павел де Рико, Александр Духов (Paul de Rico, Alexander Dukhov), as published at staropomor.ru

Further reading

[edit]- Dmitri Mereschkowski et al. Der letzte Heilige – Seraphim von Sarow und die russische Religiosität. Stuttgart 1994

- Archimandrite Lazarus Moore: St. Seraphim of Sarov – a Spiritual Biography. Blanco (Texas) 1994.

- Michaela-Josefa Hutt: Der heilige Seraphim von Sarow, Jestetten 2002, Miriam-Verlag, ISBN 978-3-87449-312-3

- Igor Smolitsch: Leben und Lehre der Starzen. Freiburg 2004

- Metropolit Seraphim: Die Ostkirche. Stuttgart 1950, pp. 282 ff.

- Paul Evdokimov: "Saint Seraphim of Sarow", in: The Ecumenical Review, April 1963

- Iwan Tschetwerikow: "Das Starzentum", in: Ev. Jahresbriefe; 1951/52, pp. 190 ff.

- Claire Louise Claus: "Die russischen Frauenklöster um die Wende des 18. Jahrhunderts", in: Kirche im Osten, Band IV, 1961.

- Bezirksrichter Nikolai Alexandrowitsch Motowilow: Die Unterweisungen des Seraphim von Sarow. Sergijew Possad 1914 (in Russian)

- Bishop Alexander (Mileant), "Saint Seraphim of Sarov", Orthodoxy and the world, December 2007.

External links

[edit]- Quotes by St. Seraphim of Sarov at Orthodox Church Quotes

- St. Seraphim of Sarov life, writings and icons Archived 14 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine on Kursk Root (Korennaya) Icon Hermitage of the Birth of the Holy Theotokos site

- On the Acquisition of the Holy Spirit Spiritual conversation of Saint Seraphim

- A wonderful revelation to the world, www.stseraphim.org

- Uncovering of the relics of the Venerable Seraphim of Sarov Orthodox icon and synaxarion

- Glorification of Saint Seraphim. Sarov, 1903

- Photos of St. Seraphim glorification solemnity in Sarov (1903), Martha and Mary Convent site

- Photos of St. Seraphim glorification in Sarov (high res images), sarov.net

- St. Seraphim's biography by Archimandrite Nektarios Serfes

- Portal devoted to 100-th anniversary of St. Seraphim of Sarov glorification (in Russian)

- English page on Sarov monastery web-site

- 1759 births

- 1833 deaths

- 18th-century Christian saints

- 18th-century Christian mystics

- 19th-century Christian saints

- 19th-century Christian mystics

- Christian ascetics

- Eastern Orthodox mystics

- Russian Eastern Orthodox priests

- Russian saints of the Eastern Orthodox Church

- Hesychasts

- Starets

- Miracle workers

- 18th-century Eastern Orthodox priests

- 19th-century Eastern Orthodox priests

- Anglican saints