Blond Angel case

The Blond Angel case or Petite Maria case started with the search for the biological parents of a blonde girl found by Greek police in a Romani camp on October 16, 2013. Eight days later, after taking on an international dimension with the involvement of Interpol and an appeal for witnesses launched by the child protection association "The Smile of the Child", the investigation led to the identification of the parents, Atanas and Sacha Roussev, in a Romani camp in Bulgaria. Both confirmed that they had entrusted their daughter shortly after her birth to Christos Salis and Eleftheria Dimopoulou, the couple with whom she had been found. On November 9, 2015, they were acquitted of the kidnapping charge for lack of evidence. The child, Maria Roussev, remained in Greece, in the care of the association.

The case led to a series of reforms within the Greek administration, highlighting the shortcomings of the civil registry as one of the factors in the child's situation. Above all, it was the subject of ten days of intense media coverage around the world, and especially in Europe, before disappearing from the news once the biological parents had been found. The media coverage led to the emergence of several similar cases across the continent, notably in Ireland, where two other "blond angels" were taken from their Romani parents by the authorities. Official and associative reactions followed, most notably from the Council of Europe's Commissioner for Human Rights, who denounced the risks of stigmatization associated with the spread of prejudices based on stereotypes.

The case, in which a police investigation triggered a media frenzy that was as intense as it was fleeting, has given rise to numerous analyses. Depending on the angle chosen, those that aim to shed light on the context highlight the vulnerability of Romani minorities to child trafficking, the particular severity of the discrimination they suffer in Greece, the "official invisibility" that surrounds them throughout Europe, or a political climate marked by a continent-wide tightening of national policies against them. From the point of view of social work and the intentions of the police and child protection associations, the case seems emblematic of the perverse effects inherent in the creation and exploitation of a "moral panic". An analysis of the media's treatment of the case highlights the role played by representations of the Romani people, whether in explaining the media frenzy, in the initial dramatization of the case by the Greek press, or in the qualitative shortcomings of its European coverage and across the diversity of national situations. An examination of these representations reveals the racial assumptions behind the image of the "blonde angel" and the fantastical nature of the child-stealing Romani, as opposed to the concrete harm suffered by Romani families and communities.

Course of events

[edit]In Greece

[edit]On October 16, 2013,[1] in a Romani camp near Farsala, in central Greece,[2] police officers conducting a routine[1] search for drugs and weapons[2] were struck by the appearance of a four-to six-year-old girl: her blond hair, very pale skin and green eyes set her apart from both the four matte-skinned children she was playing[1] with and the dark-skinned brunette[3] couple staying nearby.[1] Christos Salis and Eleftheria Dimopoulou, then aged 39 and 40 respectively,[2] claimed to be Maria's adoptive parents,[1] but neither could provide any proof.[4] The police removed the girl from the camp[5] and entrusted her to the care of "The Smile of the Child" association.[1]

DNA tests confirmed that the two Romani men were not the child's biological parents. When questioned, they successively gave several explanations: according to one, she had been entrusted to them in Crete by her father, a Canadian national; according to another, they had found her at the entrance to a supermarket;[1] finally, they declared that they had been given custody of her by her mother, a Bulgarian Romani woman who was unable to look after her, shortly after the birth.[6] Suspected of having kidnapped or bought the little girl to take advantage of welfare benefits and, ultimately, a forced marriage,[4] they were charged on October 21 with kidnapping, as well as with forging documents for the declaration of birth made in 2009 at Athens town hall. The couple have been remanded in custody pending trial.[6]

Internationalization

[edit]

By turning to Interpol, the Greek authorities decided to internationalize the case.[1] The police director for the Larissa region, Vassilis Halatsis, told the press: "We are getting information from all over Europe which shows that this problem, of children going missing and falling into gypsy hands, is a problem throughout the continent".[7] To determine whether the girl has been abducted or trafficked,[8] the international police cooperation organization first compared her genetic profile with those registered in its worldwide database. Failing a match, it asked its 190 member countries to carry out the same check in their national databases.[9] Maria was not found on any of the lists of wanted children.[10]

For its part, the association "The Smile of the Child" launched an appeal for witnesses, which received between 8,000 and 9,000 replies.[1] Eight cases of missing children from several countries,[10] including the United States, Sweden, Poland and France, were extracted and examined in depth.[6] These include the case of Lisa Irwin, reported missing in 2011 at the age of 11 months[1] from Kansas, and that of Greek parents, one of them of Scandinavian origin, who lost a daughter at birth in 2009, whose body was never returned to them, and who after obtaining an exhumation found her coffin empty.[10]

In Bulgaria

[edit]The last version given by the two suspects enabled the search to be traced back to a Romani camp in Nikolaevo, Bulgaria. Many of the camp's inhabitants had the same physical characteristics as the girl. According to a neighbor, a woman named Sacha Roussev was moved when she saw the child found on television. When questioned on October 24, 2013, she photographed the couple to whom she had entrusted her daughter in 2009. DNA tests confirmed that she and her husband Atanas Roussev were Maria's biological parents.[1] A check at Lamía hospital revealed the birth certificate, dated January 31, 2009.[11]

The Bulgarian courts opened an investigation into child abandonment.[1] The authorities plan to remove seven of the Roussevs' children from their care and place them in various foster homes.[12] The testimony of Anton Kolev,[3] a cousin, sheds light on their behavior at the time of their daughter's birth: they were in Greece picking peppers at the time, in an illegal situation and without the necessary means to obtain papers to bring her back to Bulgaria with them.[13] They claim to have received no financial compensation, citing the precariousness of their living conditions since then; according to a relative, they nevertheless received the 300 euros needed for their own return to Bulgaria.[1] The couple explain that they were not in a position to take care of the little girl at the time, but that they now wish to resume responsibility for her.[2]

At the same time, Maria Roussev, under the care of the association "The Smile of the Child", spent several days in hospital, where she underwent a series of medical tests. There was then talk of her being taken in by a Bulgarian welfare center for a few weeks or months, before being placed with a Bulgarian foster family.[1]

Judicial outcome

[edit]On June 30, 2014, the Larissa court decided to leave Maria in the care of the Greek association "The Smile of the Child". Its president, Kostas Giannopoulos, pointed out that he had not made any such request, nor had the biological parents, the only complaint having been made by the Bulgarian child protection agency.[14] Although she used to speak only Romani,[15] according to the association, she has now learned to speak both languages fluently. The two defendants have meanwhile been released, pending trial.[14]

On November 9, 2015, the Larissa Court of Appeal acquitted Christos Salis and Eleftheria Dimopoulou of the kidnapping charge, for lack of evidence. For using false documents, they were sentenced to 18 months' and two years' imprisonment respectively, suspended. At the same time, Maria Roussev was still being cared for in Greece by "The Smile of the Child",[2] and had started school. According to the psychologists looking after her, she is gradually recovering from the traumas she has suffered.[16]

Repercussions

[edit]For the Greek administration

[edit]

The arrest of the suspect couple brought to light the flaws in the birth registration system,[17] identified as one of the causes of the case.[8] At the time of the events, the centralized register had only been in existence for five months.[10] Eleftheria Dimopoulou had registered six children in Larissa since 1993, and another four under a different identity in Trikala, also in Thessaly. Christos Salis, for his part, has registered four children in Farsala. Of the fourteen children declared by the couple (ten of whom are nowhere to be found),[10] six were allegedly born in less than ten months. Maria was registered beyond the legal deadline of one hundred days after birth, and her adoptive mother used a false identity for one of the two testimonies required. In total, the couple received 2,790 euros per month in child benefit.[17]

The prosecutor in charge of the case emphasized that the case was not necessarily unique, and that a similar case could have happened elsewhere in the country.[8] The mayor of Athens launched an audit of the local civil registry; several of the employees in charge of births were suspended[17] and their director dismissed.[6] At national level, the Court of Cassation ordered an investigation into all birth certificates issued since 2008,[8] with the exception of those declared by hospitals.[17] Following this measure, several cases of birth declarations considered suspicious by the authorities were examined by the courts.[18]

For the media

[edit]The case was immediately covered by the media on an unusual scale. In Greece, the discovery and physical characteristics of Maria fueled intense media activity.[19] The country's media widely circulated photos of the little girl, whom they dubbed the "Blond Angel". The nickname was picked up by the world's press[1] when, three days later, the story was picked up[10] by news agencies (AFP, AP and Reuters in particular): by October 19, the child's face was visible in much of the media, in Europe and beyond.[5] In addition to the responses to its appeal for witnesses, "The Smile of the Child" association recorded 200,000 visits to its website, and half a million to its Facebook page.[1]

The media frenzy lasted ten days. Much of the European press endorsed the police theory of kidnapping,[5] and took up the theme of Romani child thieves.[19] In British newspapers, particularly tabloids such as The Sun, The Daily Mail, The Daily Mirror and The Daily Telegraph, each of which published dozens of articles in a week, the stolen-child theory was linked to the cases of missing children that were regularly followed up.[5] Interest in Maria is fuelled in particular by the high-profile disappearance of two blond British children: Madeleine McCann in Portugal in 2007, and Ben Needham in Greece in 1991.[8] In the case of "Maddie" McCann, the Portuguese courts were about to reopen the case that had been closed five years previously.[10]

In addition to mass reproduction of agency dispatches, the media, and in particular the written press, in Europe and elsewhere, often added their own editorial content. Special correspondents like the Sun described the living conditions in the Romani camps.[5] The portrait of little Maria varied. While initially she is most often described as a blonde with green, sometimes gray-green eyes, articles soon declared her eyes to be blue. Others added to her story: the girl had been raised "to be given in marriage at her 12th birthday", or abducted "to be sold"; she had been forced to beg in the streets or dance in front of camp families; a poor-quality video, in which a blonde child does a few dance steps with a couple of adults, was supposed to show "Maria, shimmying with a pale complexion, her eyes haggard".[10]

Some newspapers emphasize the clichés to which the Roma are subjected, and denounce a racial or racist dimension in both the police and media handling of the case. The Guardian criticized media hype and stereotyping. Le Monde and Libération, after relaying the initial dispatches, set out to deconstruct the prejudices underlying the "Blond Angel" theme and the "stolen child" thesis.[5]

When the suspicions of abduction widely shared by the Greek police and the media were disproved, interest waned. Maria Roussev disappeared from the news at the beginning of November.[5]

Other "blonde angels"

[edit]On October 22, it was announced that a second "blond angel"[10] had been found the day before in a Romani camp in Ireland: in Tallaght, on the outskirts of Dublin,[20] following an anonymous tip-off on Facebook,[4] police held a seven-year-old girl for two days,[20] despite the birth certificate and passport given by the family.[8] A similar scenario occurred with a two-year-old boy detained for the same day in Athlone, in the center of the country.[20] In both cases, the Irish authorities took a child away from a Romani family because he was blond and blue-eyed, unlike his siblings; until DNA tests concluded that he was indeed his parents' child.[1]

These new cases of "blond angels" were prompted by media coverage of the Greek affair, on which the Irish media had begun, as elsewhere, to follow the lead of their Greek counterparts. By following suit, the police triggered a reversal of direction. From October 22 onwards, dozens of articles in the daily papers denounced prejudice against the Romani and the family dramas it entailed, as well as the excesses of official services accused of engaging in racial profiling. These criticisms prompt a return to the Greek case, where the same failings are denounced.[5]

In marginalized communities such as Serbia, Romani people were reporting an upsurge in racial discrimination.[8] In Novi Sad, skinheads attempted to kidnap a child in front of his home because his Romani father, Stefan Nikolic, was not as fair-skinned as him;[21] however, the assailants fled when the father threatened to call the police.[22]

Two other cases, which appeared during the same week, were at the same time relaunches of the Ben Needham affair. In Thessaloniki, northern Greece, a young, fair-haired Romani man was suspected of being the blond child who had disappeared on the island of Kos on July 24, 1991, and underwent DNA testing. At the same time, the Kos police received video footage of a religious ceremony filmed near Limassol, in southern Cyprus: in the midst of a group of Roma, a young man with light brown hair and blue eyes appeared, resembling the composite of the missing child.[23] Alerted by Interpol, the Cypriot police issued wanted notices illustrated with images from the video. On October 28, a young man who recognized his photo in the video presented himself to the Limassol police and agreed to take a DNA sample. As in the previous case, the test results were negative.[24]

Reactions

[edit]

In Italy, the Lega Nord reacted to suspicions that the couple who raised Maria had been kidnapped by calling for all Romani communities in the country to be inspected for the presence of lost children. League deputy Gianluca Buonanno announced that he would be sending a petition to the Ministry of the Interior demanding identity checks on camp residents.[21]

Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights, Nils Muižnieks declared: "In the case of the children found in Romani families in Greece and Ireland, most of the media, and not only in Europe, insisted on the ethnicity of the people incriminated, spreading the old myth that makes the Romani look like child abductors";[25] he denounced this attitude as "irresponsible coverage", likely to have significant consequences on the lives of millions of Romani.[19] Its 2013 annual activity report echoed this stance, while resituating the cases in question in the context of "the hysteria aroused by the alleged imminent mass movement of Romani from Romania and Bulgaria to other European Union countries due to the imminent end of restrictions on the free movement of citizens of these countries".[26]

Several non-governmental organizations concerned with the problems of the Romani used the case to demonstrate the presence of negative stereotypes and prejudices against them in European society.[27] Dezideriu Gergely, head of the Budapest-based European Roma Rights Centre (ERRC), pointed out that not all Romani are dark-skinned, and that some are light-skinned and green-eyed,[8] and deplored the effect of the propagation of hostile prejudice in the Irish case. The Center denounced the generalizations that fuel the stigmatization of the community in many European countries.[1]

Kondylia Gogou, responsible for Greece and Cyprus at Amnesty International, accused the Greek media of encouraging misinformation and discrimination by claiming that Romani cannot integrate.[25] On the occasion of its 2014 report on racist violence against Romani in Europe, the organization looks back at the case, which it credits with bringing their treatment in Greece to the fore. The media's lack of interest, once it had been established that the child was Romani, is seen as "an emblematic sign of hostility and rejection towards an already marginalized community".[28]

Regarding the two Irish "blond angels", in a report published in July 2014, Children's Ombudsman Emily Logan concluded that racial profiling had indeed taken place, that the suspicions of abduction had no basis other than preconceived ideas endorsed under the influence of the media hysteria surrounding the Greek case, and that no immediate urgency justified the actions taken. Both families received official apologies from the authorities concerned.[29] Subsequently, training to prevent any form of discrimination or ethnic profiling was introduced in the national police force, the Garda;[30] in October 2015, the parents of the Athlone boy, who took legal action against the Ministry of Justice, the Garda Commissioner and the State, were awarded 60,000 euros in damages for negligence, arbitrary imprisonment and emotional harm.[31]

Analysis

[edit]Context

[edit]Child trafficking and Romani communities

[edit]On the BBC News website, Paul Kirby took up the general data on child trafficking activities around Romani communities: UNICEF estimated that at least 3,000 children in Greece were in the hands of networks originating from Bulgaria, Romania and other Balkan countries; most cases were probably not the result of abductions, but rather purchases and sales concluded for a few thousand euros. For the international organization, Romani communities were often used by traffickers because they were "below the radar of society". Similarly, the European Roma Rights Centre (ERRC), while refusing to link the fact to cultural or community factors, acknowledged that the Romani are a vulnerable group, due to their extreme poverty and low levels of income and education.[8]

Vincent Vantighem, on the website of the French edition of the free daily 20 minutes, summarized the precedents that guided the early stages of the investigation: in 2011, at the height of child trafficking between Bulgaria and Greece, police cooperation between the two countries led to the arrest of ten Bulgarians and two Greeks, accused of taking 17 pregnant Bulgarian women to Greece to sell their newborn babies. According to experts, operations of this type were facilitated by loopholes in Greek adoption legislation, particularly concerning foreign children. According to police sources, intermediaries earn between 15,000 and 20,000 euros per child.[6] In September 2014, while Maria Roussev's parents were still suspected of having sold their daughter, Clémentine Fitaire, on the Aufeminin website, made the connection with a new case of child trafficking that the Greek police had just announced had been dismantled: six individuals, including a pediatrician and a notary, were bringing pregnant women in precarious situations from Bulgaria to Greece, to give birth; the babies were then resold to couples applying for adoption, for around 10,000 euros.[32] In November 2015, when Christos Salis and Eleftheria Dimopoulou were acquitted of kidnapping charges, the Greek website Ekathimerini.com recalled that, according to the Ministry of Justice, dozens of cases of child trafficking and illegal adoptions were being investigated, some of which involved doctors and private clinics; among the explanatory factors cited were the low birth rate and cumbersome adoption procedures.[33]

Romani in Greek society

[edit]Ermal Bubullima, of the Courrier des Balkans, noted that the case had led the Greek media to raise the question, usually passed over in silence, of the economic and social situation of the Romani in the country, which he outlined in broad strokes: first appearing in Greece's history in the 11th century, the Romani, now estimated to number around 300,000, often lived in deplorable conditions and suffer multiple forms of discrimination; the Greek NGO Réseau Rom estimates that 83% of Romani camps had no access to electricity; running water and sanitation were also rare, and settlements were frequently located on noxious sites, near slaughterhouses or landfill sites. In May 2013, Greece, which had already been sanctioned for school segregation in 2008, was condemned (along with the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Slovakia) by the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) for allowing Romani children to be excluded from certain elementary school, and setting up separate schools for them.[25]

On the news and opinion website Equal Times, Katerina Penna recounted how the Greek economic crisis and its aftermath had intensified backlash against minorities and migrants. Faced with disproportionate levels of unemployment and growing discrimination, the Romani are easily blamed for crime, underemployment and instability. Their situation was further worsened by the progress of the far-right Golden Dawn party, which often violently attacked them.[34]

In October 2014, a year after the affair broke, Nikolia Apostolou, an Athenian writer and filmmaker writing on the Open Society Foundations website, noted no significant improvement, but rather a strengthening of prejudice. There were signs of progress here and there: in Examilia, near Corinth, for example, after years of effort, the young players of the Romani soccer team noticed a change in the attitude of the inhabitants of the neighboring town, who now come to watch their matches. But the ten-year program of cooperation with Romani communities, which was supposed to tackle the problems of schooling, health, housing and work, has had trouble finding its way into national and local reality.[35]

Aspects and implications of the administrative situation of the Romani in Europe

[edit]Speaking to The Guardian, Zeljko Jovanovic, himself of Romani origin and director of the Roma Initiative program (an association of the Open Society Foundations network[13]), pointed out that, due to malnutrition and poor housing and hygiene conditions, the 12 million or so Romani living in Europe have a life expectancy 10 years lower on average than the rest of the population.[36] A study carried out in 2012 in eleven European countries also revealed that 90% of Romani families live below the poverty line in their respective countries, and that 15% of them have completed secondary school.[35] In the eyes of the association leader, the absence of a valid birth certificate and papers for Maria illustrated a major cause of this situation of exclusion: the lack of official documents. The resulting "official invisibility" excluded Romani not only from the protection of the law, but also from medical care, schooling, job-seeking and participation in elections.[36]

As Paul Kirby has pointed out, since the mid-1990s, the European Union has been seeking to achieve the full registration of all Romani across Europe. 95% of them are settled, so the operation does not in principle raise any particular administrative problems. However, despite all efforts to register them in national databases, many Romani families continue to fall outside the system.[8]

According to the picture painted by Zeljko Jovanovic, no European country has precise official statistics on the Romani population; many Romani do not have a birth certificate, as they fail to declare themselves, and the cost of the document is sometimes prohibitive; some avoid declaring their identity for fear of discrimination: the hundreds of thousands of victims of Nazism remain a vivid memory in the community, and present fears are not always imaginary (for example, the Swedish police have maintained an illegal list of 4,000 Romani). Added to this are the legal and procedural difficulties which, according to the association leader, often and deliberately prevent people from obtaining identity documents: in his view, they show that the invisibility of the Romani is politically and economically convenient for governments which would otherwise have to guarantee their access to education, health, justice, representation in the civil service, participation in elections, etc. Lack of official identity makes them easier victims of human trafficking or judicial dysfunction, and often subjects them to the risk of being considered stateless.[36]

Direction of political measures and discourse on the Romani in European countries

[edit]For Daniel Bonvoisin, a member of the Média Animation[37] website team, the case and, above all, the media coverage it received, should be seen in the context of the political climate surrounding Europe's Romani minorities at the time: since the 2000s, these populations have been the subject of restrictive national measures aimed at their encampment or, in the case of foreigners, their repatriation to their country of origin, most often in Central and Eastern Europe (Romania, Bulgaria or Kosovo); France, Germany and Italy are particularly prominent in these policies, which have intensified since 2010, with the French government stepping up its expulsions.[5]

According to this analysis, the origin of this situation can be traced back to the accession to the European Union of the countries in the central and eastern part of the continent: this made their Romani nationals fully-fledged European citizens, who were supposed to be able to enjoy the freedom of movement that is at the heart of the Union. In 2013, tensions were heightened as the end of the restrictions imposed on Romania and Bulgaria's integration into the Schengen Area, scheduled for 2014, approached. Added to the general mistrust of these countries' ability to control their migratory flows is concern about the Romani.[5]

Daniel Bonvoisin has noted that there is much rhetoric in favor of strengthening control policies, without always avoiding clichés. The far right was no stranger to this:[5] in Hungary, in 2011, journalist Ferenc Szaniszló compared the Romani to monkeys, though this did not prevent him from subsequently being decorated by Viktor Orbán's government;[38] in France, in July 2013, Jean-Marie Le Pen predicted a flood of 12 million Romani, all of whom he saw "in the starting-blocks".[39] But the theme reached a wider political spectrum. In September 2013, referring to the dismantling of camps, the French Interior Minister, the Socialist Manuel Valls, declared, "These populations have lifestyles that are extremely different from ours, and which are obviously in confrontation, we have to take that into account, it does mean that the Romani are destined to return to Romania or Bulgaria." The following month, on the subject of opening the borders to Bulgarian and Romanian workers, David Cameron, the British Conservative Prime minister, warned: "if people are not here to work — if they are begging or sleeping rough — they will be removed". In the eyes of the specialist in intercultural relations, although they concern different measures, the two speeches communicated the same message about the incompatibility of lifestyles between Romani minorities and what were becoming delicate to call "host societies".[5]

Beyond the immediate context, writer Patrick McGuinness saw in this attitude of hostility, in this "passive-aggressive logic", the expression of a point common to all countries, whether in the West or East of the continent, where the Romani constitute a significant minority: failing to identify with a territory, they seem to question the very idea of national identity, setting in motion a game of mutual exclusion in which the majority cultures, in order to justify rejecting them, presume to be rejected by them.[40]

Child protection and "moral panic"

[edit]In terms of child protection, Jana Hainsworth, from the Eurochild network of associations, has found the case to be an illustration of an all-too-common trend: the demonization of "bad" parents, to the detriment of a more attentive approach to the complexity of families' situations.[12] For both her and Huus Dijksterhuis, of the European Romani advocacy network ERGO, separating a child from his or her family is a solution that should only be considered as a last resort, and should not detract from efforts to help marginalized communities, based on a systemic analysis of the causes of their exclusion. In this respect, both welcome the steps taken in Ireland to implement the recommendations of Emily Logan's report.[41]

For Viviene Cree, an academic specializing in social work, who is developing this analysis with Gary Clapton and Mark Smith,[42] the case had all the hallmarks of a "moral panic":

- social actors perceived as a threat to society: in this case, the "child-stealing" Romani;

- the media portrayed them in a stylized, stereotyped way: in fact, media coverage of the affair was highly emotional, revealing an underlying racism in the evocation of the "Blond Angel";

- the building of "moral barricades" and the production of diagnoses and solutions by socially recognized experts: in this case, it was the media that fulfilled this role, with associations and child specialists generally refraining from any direct involvement;

- evolving methods of treatment, with repercussions that were difficult to control: even before the long-term results of the case could be assessed, it was already possible to point out that, when it comes to social work, "the road to hell is paved with good intentions".[4]

Indeed, according to Viviene Cree, there's no denying that concern for the child's welfare and protection was part of the police officers' motive. And yet, from the very first days after Maria's discovery, it was already clear that she was neither a stranger nor an unloved child in the Farsala camp. According to residents' testimonies, her situation was neither the result of kidnapping nor human trafficking, but rather of a form of informal adoption; moreover, her biological father continued to visit her, most recently five days before the investigators intervened, while her mother was in Sofádes, a village a few dozen kilometers away. Video footage of the little girl dancing, community testimonials and family photos show a happy and pampered child, not only by the Romani couple, but more broadly by the extended family in which she lived. Maria was then placed in a reception center and stayed there. While it would seem possible that she will one day be adopted outright, it is unlikely that it will be by the Romani family in which she spent the first five years of her life. Such an outcome left the specialist sceptical as to its consistency with the initial good intentions.[4]

More generally, this case illustrated the risks of manipulating moral panics. Associations and institutions were inclined to create or maintain these phenomena, to raise awareness and support their own understanding of social problems. However, their consequences were often negative, whether intentional or not, reinforcing stereotypes and attitudes of withdrawal rather than moving towards greater justice and equality. Social workers therefore needed to face up to the complexity of these situations, aware of the role they play in them by virtue of their profession.[42]

Media operations

[edit]Reasons for the media frenzy

[edit]Daniel Bonvoisin's assessment of the media coverage of the case was less remarkable for its content than for its scale: the almost unanimous interest shown by the continent's media was exceptional for a news item concerning the Romani.[5] The French news website Le Huffington Post, seeking to identify the reasons for this hype, first noted the mystery in which the investigation began. On October 19, speaking to the press, the regional police spokesman mentioned several possibilities: abduction from a hospital, as the result of an isolated act or as part of a trafficking operation, abandonment by a single mother. In addition to the multiplicity of hypotheses put forward by the investigators, there was also the multiplicity and obscurity of the versions successively provided by the suspect couple. One of these, attributing a Canadian origin to the child, also led to the involvement of the North American media.[1]

For Jean-Laurent Van Lint, of the weekly Moustique, fascination with the case is also fueled by the image of "threatened purity" conveyed by the figure of the "blond angel", an image behind which unfolds "in filigree the story of a little Aryan girl in the clutches of a barbaric race". According to the journalist, this drift, whether conscious or not, often combined with a sense of misery to frame the case against the Romani, makes the whole affair seem like a "Dickensian novel".[10] In Daniel Bonvoisin's view, these images, and more generally the "imaginary of the Romani", were the driving force behind media discourse. As he noted, clichés remained at the heart of the discourse, even in texts that aim to deconstruct them and denounce their stigmatizing dimension. In his view, the media's treatment of this issue was conditioned by a European discourse that was largely suspicious of the Romani, and the magnitude of the affair shows just how powerfully the media can be driven by prevailing representations of a minority, coupled with a specific political climate towards it.[5]

Analyses all agreed on the emotional effectiveness of the "lost child" theme. Among the calls to "The Smile of the Child" association were those from parents who have lost theirs, and for whom this is a moment of hope.[1] For example, for Ben Needham's family, the start of the investigation reactivated the possibility of a Romani abduction.[10] More generally, for any parent, losing a child is the worst fear of all.[10] And when, as in the Irish press reversal, the dialectic of the cliché and its deconstruction have shown their limits as a factor of dramatization, the defense of the threatened family unit remains a recourse, even if for the benefit of Romanis admitted on this occasion to the status of citizens and parents.[5]

The drop in public interest, once the girl's Romani parents have been identified, marks the exhaustion of these resources.[36] The conclusion of the Moustique article puts it this way: "Since it became known that this was a very poor child entrusted to the care of people who were a little less poor, Maria has disappeared from the headlines.[10]

Greek media coverage

[edit]On the website of the European participative magazine Cafébabel, Giannis Mavris assessed the coverage of the case by the Greek media, which he pointed out were particularly distrusted in this country, not least for having played no warning role before the economic crisis. After the discovery of the little girl and the DNA tests proving that she was not the biological child of the couple raising her, most newspapers did not hesitate to launch the hypothesis of an abduction, with only a few warning against hasty conclusions. What's more, media bias and the exaltation of prejudices to the effect that Romani "are not civilized people" did not spare some of the most reputable press outlets, albeit in barely attenuated form.[43]

On the website of the Institute of Race Relations, Ryan Erfani-Ghettani reminisced about how the Greek television stations (Alpha and Skai) in Farsala exploited family videos and expressions of affection from the neighborhood: to show that the little girl was raised by the whole community with the aim of making money, first through begging, then through the sex trade. Subsequently, due to a reaction of defiance from the camp's inhabitants, the BBC cameras were turned away, leaving the impression that the camp was trying to protect a secret parallel life.[44]

For Giannis Mavris, the outcome of the case – the absence of proven criminal activity and little Maria's Romani ancestry – revealed the power of xenophobic stereotypes. However, the press did not look back. Most newspapers opted for silence, and the outcome of the affair was treated with great sobriety. This lack of self-criticism leaves the observer pessimistic about the possibility of restoring confidence in the media in Greece.[43]

Quality of international news coverage

[edit]As for the international media, according to Natasha Dukach's analysis on the Fair Observer website, they did not sufficiently verify the information produced by the Greek press and repeated a biased presentation of the case, contributing to the promotion of stereotypes. These included their silence on the fact that little Maria's ethnic origin had been stated from the outset of the investigation by the couple who raised her; or the propagation of false information, such as the assertion that the child's biological mother had taken the initiative to claim maternity, when she was only identified following a search and after DNA tests had ruled out all putative parents.[45] Krystal Thomas, author of an academic work on the situation of the Romani in the European Union, highlighted how Maria's "mystery", by occupying the headlines, put these populations under the gaze of the rest of the international community:[46] her instant disappearance, without any analysis of the negative stereotypes that had been disseminated, ultimately led to increased discontent.[47]

Estrella Israël-Garzón and Ricardo Ángel Pomares-Pastor, respectively professor[48] and researcher[49] in communication sciences, for their part studied how the affair was covered by the television news of several European public channels (BBC, France 2, Rai 1 and La 1), from October 19 to 22, 2013. The main finding is that the presentation of the news contributed to the stigmatization of the populations involved, notably through an ethnicization of the facts contrary to the quality standards in use.[50]

The stigmatization was evident first and foremost in the images presented. Views of the Farsala encampment reveal the group's marginality.[51] In the photographs in which Christos Salis and Eleftheria Dimopoulou are shown with the little girl, they are shown side by side, their gazes parallel, as if they didn't know each other.[52] The front and side portraits of both parents, obviously taken by police officers, criminalize them from the outset. The shots of the child are almost all serious and sad.[53] Two of them, commented Isabelle Ligner on the association website Dépêches tsiganes, operate in a "before/after" mode: while the first showed her in crumpled tracksuits, her head disheveled and her face dirty, the second, where a smile appears on a clean face topped by a well-coiffed head of hair, suggested how the good treatment lavished on her by the authorities contrasted with the negligence of the Romani couple.[3]

According to the two academics, it is the primacy given to the emotional over the informative content that leads to the emphasis on the negative, the spectacular and the uncertainty surrounding the identity of the little girl, a "blond angel" surrounded by dark-skinned suspects.[52] The child's appearance was supposed to be enough to rule out the possibility that her parents might be Romani. As for the ethnicization resulting from the insistence on assigning people to an ethnic identity, a common and constant feature of the treatment of the case,[52] its systematic nature contradicted the codes of journalistic deontology established by the television stations themselves.[51] "Through the generalization," they noted, "a division is established between 'us' – the 'whites' thrown into the search for the real parents – and 'them' – the marginalized, kidnappers, child and drug traffickers -".[nb 1][51]

Although mainly based on police sources, the information presented also gave the floor to representatives of the Romani community. A clear effort was made to present all versions of events, which can be seen as progress in the coverage of this type of case. The viewpoint of an NGO ("The Smile of the Child"[54]) was presented, and reference was made to human rights groups. However, in the majority of cases, the contextual information needed for understanding was lacking. The case was presented as a global news item, according to presentation criteria that did not differ significantly between public and private media.[51] As the days passed, attention shifted from the kidnappers to the search for the biological mother; after the identification of the latter in Bulgaria, announced on October 25, media interest, significantly reduced,[55] shifted from the search for the authentic progenitors to the ethnic question.[51]

Ultimately, for the two academics, the coverage of the case, which deviated from the applicable quality standards, showed how "necessary is a more rigorous and plural treatment of information, where intercultural and ethical criteria would help to overcome the barrier of excluding difference".[nb 2][56]

Unity and diversity in European media

[edit]Daniel Bonvoisin's qualitative observation was similar: most European media were content with a simplistic treatment based on agency dispatches and stereotypes. In his view, their convergence around a relatively uniform theme was indicative of the generalization across the continent of the same image of the Romani, who had become a European-wide reprobate. In his view, this trend was in line with the hardening of political discourse on these minorities: a climate devoid of nuance encouraged the press to relay rumors with a single voice.[5]

On this basis, the analyst compared the British, French and Irish press, illustrating how the use of Romani portrayals varied according to national contexts:

- in the UK, the Romani, though relatively few in number, were regularly evoked, and usually negatively: in 2013, the imminent full integration of Bulgaria and Romania into the Schengen area had already given rise to numerous alarmist, sometimes openly xenophobic articles and political speeches; a Daily Mail report had thus anticipated the move to Britain of half a Romani village on January 1, 2014. The undifferentiated treatment given to the case by the country's media, with a few exceptions and illustrated, among other things, by their descriptions of the Pharsalus camp, was in line with political rhetoric hostile to immigrants from the East; above all, it made it possible to exploit the traditional audience spring provided by cases of missing children, an important economic element in particular for the tabloids;

- in France, the Romani question was a recurring theme of public debate; the expulsions and dismantling of camps that marked the presidencies of Nicolas Sarkozy and François Hollande have been joined by news stories: in July 2013, Gilles Bourdouleix's statement, "Hitler may not have killed enough of them", which quickly had this centrist elected official excluded from his party; those, the same month, of right-wing deputy Christian Estrosi, making a point of "subduing" illegal Romani; the Leonarda affair, in October 2013; subsequently, in June 2014, that of the lynching of Darius, a young Romani. The case of the "Blond Angel" was part of an already polarized context, between media outlets primarily concerned with solving the "Romani problem" and others that favored an anti-racist, critical approach. This polarization was reflected in the handling of the affair, which on the one hand saw Le Figaro give the floor to a Greek elected official for comments very similar to those made by certain French mayors, and on the other anthropologists develop in Libération a "myth-buster" capable of countering stereotypes;

- in Ireland, the Romani were relatively under-represented, not only demographically, but also in the media. The media had not yet been trained in the idea of a "Romani problem". On the other hand, they were particularly sensitive to the issue of child abuse in public institutions, which had regularly been the subject of revelations since the 1990s. These circumstances may explain why, in the case of the Irish "blond angels", they have turned their attention to defending Romani families against abuse by the police and social services.[5]

With regard to the Irish case, Ryan Erfani-Ghettani pointed out that, prior to this inflexion, the press, influenced by the Greek case, had indeed succeeded in creating a self-sustaining hysteria, with rumor-driven actions by the authorities becoming evidence of the reality of the abductions; and that Emily Logan's report had also reminded the media of their obligations, notably in terms of privacy protection (the released little girl had not been able to return to her home besieged by journalists).[44]

Portrayals and attitudes towards the Roma

[edit]Racial background of the "Blond Angel" image

[edit]

For historian and political scientist Henri Deleersnijder, the case provided an example of the particularly abusive generalizations that fuel hostility towards the Romani.[57] In Daniel Bonvoisin's view, the magnitude of the affair also provided an ideal opportunity to analyze the media discourse on these populations. He pointed out that it had its origins in a rumor which, like the one in Orléans, combined the theme of kidnapping with a racist slant: non-Romani children, as evidenced by the color of their hair and eyes, were allegedly kidnapped by Romanis, for whom this was a habitual activity. Thus, by subscribing to the police hypothesis of the kidnapping, a large part of the European press subscribed to the prejudices on which it was based, and the media hype revealed first and foremost the racial background that structures the imaginary world of the Romani.[5] In the words of Zeljko Jovanovic, the handling of the case showed "how quickly Europe can lapse into racist hysteria".[36]

In Libération, Patrick McGuinness highlighted the thinly veiled racism conveyed by the nickname "Blond Angel" given to the little girl, the unspoken fact being that she is surrounded by "black demons".[40] For paleoanthropologist Silvana Condemi, writing in the same newspaper, implying that a little girl cannot belong to its population simply on the basis of her physical appearance, or then qualifying her blondness as a "defect in the genes coming from her parents", is still to maintain the idea of homogeneous, "pure", non-mixed populations settled on their soil since the dawn of time. This concept can be compared to the one used by the Nazis when, systematizing earlier censuses and supported by the pretentious scientific work of Robert Ritter and Eva Justin, they used anthropometric measurements of the skull and face to distinguish between "pure Gypsies" and "mixed Gypsies". Paradoxically, their results, which were to justify the worst persecutions, revealed a very high level of "miscegenation" among the German Gypsy population. No population can ever be free of a biological variability that is the product of its history, its movements, its relations with others and with its environment. Which means, for example, that it's perfectly possible to be Romani and blonde.[58]

Reawakening prejudice against Romani children-stealers

[edit]

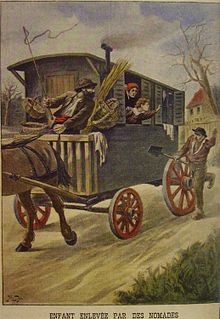

The "anomaly" constituted by the girl's blond hair was, in the words of Daniel Bonvoisin, "exorcised" by another cliché, that of the child-stealing Romani.[5] On the Atlantico website, Emanuela Ignatoiu-Sora, who worked at the University of Florence on the legal protection of the Romani, pointed out that this prejudice has long been part of European fantasies.[59] As Isabelle Ligner has explained, it was widespread in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when it was also propagated by the press in a context of repression of "nomadic" populations, considered an integral part of the "dangerous classes". "Don't dawdle in the street, or the flying camps will take you away", was still heard in the provincial France of the 1970s.[3]

Emanuela Ignatoiu-Sora contrasted this prejudice with the one that accused Jews of killing Christian children to obtain human blood for Easter. She deplored the fact that, at a time when all Romani were increasingly criminalized, the media were fuelling this process by feeding stereotypes. Yet, she highlighted, according to the anthropologists who have studied them, for the Romani, the family is one of their cardinal values, and the child a vital element; classically, Romani parents are keen to pass on their trade to boys and to marry off girls a little earlier than the European average, although this is not true of all communities. She concludes: "All these issues of criminalization, of media-fueled stereotypes, ultimately point to the economic problems and solutions that some of the Romani resort to in order to make a living".[59]

In The Guardian, Romani specialist Thomas Acton asserted that there are no proven cases of children being abducted by Travellers.[10][60] Anthropologists Marc Bordigoni and Leonardo Piasere pointed out in Libération that, in this case, the practice of child abduction by the Romani, developed in literature by Cervantes with the character of La Petite Gitane, once again proves to be a legend, as it has been for the last century in all cases for which there are records. For them, entrusting one's child to others, whether relatives, allies or strangers, as Maria's biological parents did, is a constant in the history of all populations known to ethnologists, in Europe or elsewhere.[61] According to Isabelle Ligner, in the Romani's broad conception of the family, a child can easily be entrusted informally to an uncle or "ally" of his or her biological parents, and it is common for the same couple to raise both numerous biological children and one or more children through informal adoptions.[3] For its part, the CEDR insists on the exceptional nature of Maria's case: while it may happen that children are raised within the extended family, for example by grandparents, it is rare for them to be raised completely outside their biological family.[8]

Targeting of Romani families and communities

[edit]

For political scientist Huub van Baar, the case illustrates, along with many others, the damage that unfounded allegations can cause, especially when the police, media and politicians failed to denounce the abuse of stereotyped images, if they didn't indulge in it themselves. On the other hand, little or no attention has been paid to ethnic profiling practices and the infringements of children's rights to which they give rise. The general, tacit tolerance accorded to such behavior is, for the academic, a sign of the contemporary emergence of a "reasonable anti-gitanism".[62]

In the eyes of Marc Bordigoni and Leonardo Piasere, the fate of the little girl, placed in an institution, as well as that of her adopted siblings, also placed, and the similar fate then envisaged for her biological siblings, all illustrated the same reality: in practice, it is the reinforced institutional control of family life, established in Europe from the 19th century onwards, that results in the removal of children from their family environment, "for their own good". The cases of The Children of Creuse, from 1963 to 1982 in France, and the "Children of the Open Road", from 1926 to 1973 in Switzerland, provide two examples.[61] In The New York Times, Dan Bilefsky expressed the widespread fear among the Romani scattered across Europe that their children would be taken away for no other reason than their cultural identity or skin color.[21]

In the same vein, sociologist Ethel Brooks[63] highlighted the irony of the situation of little Maria, taken away from her family because it was feared that she had been abducted, while the last century was marked, "from the British Isles to the Americas, from France to Spain, from Romania to Russia, from Australia to South Africa", by the forced removal of Romani children from their families. The case showed once again that Romani motherhood is never safe, always open to challenge.[64] As with the other blonde angels, the author saw the treatment of Maria's case as an expression of a rejection of Romani motherhood that points to a wider project, "involving the criticism of Romani mothers, the dismantling of Romani family structures, the destabilization of Romani children". Forced sterilization in the Czech Republic, school segregation in Hungary, police operations – evictions, raids, dismantling – carried out in Romani neighborhoods in Greece, Germany and France have placed the Romani, their families and their communities in a situation of permanent insecurity.[65]

Femininity, forms of motherhood and Romani mothers themselves are delegitimized, even though it is through them that children learn the language and become individuals and members of the Romani community.[64] In the face of these threats, the author called for a Romani feminism which, unlike liberal conceptions, can only be rooted in the community's resistance.[65]

Notes

[edit]- ^ In spanish: "A través de la generalización se establece una brecha entre "nosotros" — los buscadores 'blancos' de los verdaderos padres — y "ellos" — marginales, secuestradores, traficantes de niños y de drogas —".

- ^ In spanish: "se hace necesario un tratamiento más riguroso y plural de la información, donde los criterios interculturales y éticos ayuden a superar la frontera de la diferencia excluyente".

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t (fr) "" Ange blond " : pourquoi cette affaire a-t-elle autant fait parler ?". Le Huffington Post. 25 October 2013..

- ^ a b c d e (fr) M. D. (10 November 2015). "Grèce – Les parents de " l'ange blond " blanchis". Paris Match|Paris Match.com..

- ^ a b c d e (fr) Isabelle Ligner (28 October 2013). "" L'Ange blond " : la violence du racisme à l'égard des Roms". Dépêches tsiganes..

- ^ a b c d e Viviene E. Cree (17 November 2013). "How do you solve a problem like Maria?". ESRC Moral Panic Seminar Series Wordpress.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s (fr) Daniel Bonvoisin (17 November 2014). "Ange blond : les médias et les stéréotypes sur les Roms". Média Animation..

- ^ a b c d e (fr) Vincent Vantighem (22 octobre 2013 et 29 janvier 2014). "Tout comprendre sur l'affaire de « l'Ange blond »". 20 minutes.fr.

- ^ Pettifor, Tom (2013-10-18). "Kate and Gerry's "great hope": Mystery blonde girl found living with gypsies gives boost to Madeleine McCann's parents". The Daily Mirror.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Paul Kirby (23 October 2013). "Roma case in Greece raises child concerns". BBC News..

- ^ Interpol (22 October 2013). "Les autorités grecques demandent l'aide d'Interpol pour identifier une fillette inconnue par comparaison d'ADN". www.interpol.int..

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n (fr) Van Lint, Jean-Laurent (29 October 2013). "La story : l'ange blond". Moustique.be.

- ^ Anastasia Balezdrova (14 January 2014). "Maria will remain in custody of "The Smile of the Child" as decided by the court in Larissa". GR Reporter.

- ^ a b Jana Hainsworth (13–14 novembre 2013). "'Blonde angel' case: Don't demonise 'bad' parents, look at the system". EurActiv.com.

- ^ a b (fr) Dejoie and Harissou 2014, p. 20.

- ^ a b (fr) AFP/NXP (02.06.2014). "L'«ange blond» sera confié à une association". TDG.ch.

- ^ Le Bas 2015, p. 28.

- ^ Africa News Agency via Xinhua (10 November 2015). "Greek Roma couple found not guilty of abduction of girl". www.enca.com.

- ^ a b c d (fr) Gilles Trequesser, Renée Maltezou and Clémence Apetogbor (source Reuters) (23 October 2013). "L'affaire de « l'ange blond » révèle les failles de l'État grec". Capital.fr.

- ^ (fr) Le Figaro.fr (avec AFP) (12 November 2013). "Grèce : une enfant retirée à des Roms". Le Figaro.fr.

- ^ a b c (fr) Le Parisien.fr (avec AFP) (9 November 2015). "Maria, " l'ange blond " : le couple rom accusé d'enlèvement blanchi en Grèce". Le Parisien.fr.

- ^ a b c (fr) L'Express.fr (avec AFP) (24 October 2013). "Pas d'" ange blond " en Irlande : deux enfants roms ont été rendus à leurs parents". L'Express.fr.

- ^ a b c Bilefsky 2013, A1.

- ^ (fr) "Serbie : " l'ange blond " de Novi Sad était bien rom". Le Courrier des Balkans. 23 October 2013..

- ^ (fr) Avec AFP (2013-10-28). "La police chypriote recherche un jeune Anglais kidnappé dans son enfance". 20 minutes.fr.

- ^ (fr) Avec AFP (2013-10-29). "L'homme filmé à Chypre n'est pas le petit Anglais kidnappé en 1991". 20 minutes.fr.

- ^ a b c (fr) Ermal Bubullima (26 October 2013). "Grèce : Les Roms, les " anges blonds " et le racisme de tous les jours". Le Courrier des Balkans..

- ^ (fr) Muižnieks 2014, p. 8.

- ^ Thomas 2014, p. 105.

- ^ (fr) Amnesty International 2014, p. 23.

- ^ Brophy, Daragh (2014.07.01). "'Ethnic profiling' a factor in removal of Roma children, report finds". The Journal.ie.

- ^ Colin Gleeson (5 July 2014). "Garda 'challenging attitudes' in force after Roma controversy". Irish Times.ie.

- ^ Mary Carolan (19 October 2015). "€60,000 for Roma family whose blonde son (2) was removed by gardaí". Irish Times.ie..

- ^ (fr) Clémentine Fitaire (2014.09.25). "Un trafic de bébés démantelé en Grèce". Aufeminin.

- ^ AFP (9 November 2015). "Greek Roma couple cleared in bombshell child-snatching case". Ekathimerini.com..

- ^ (fr) Katerina Penna (28 January 2014). "« La petite Maria » et la discrimination envers les Roms en Grèce". Equal Times.

- ^ a b (fr) Nikolia Apostolou (2014-11-01). "Ce n'est plus une Breaking News : la vie des Roms en Grèce un an après l'épisode " Maria "". Okeanews.fr (in French). ; translated from "Breaking News No More: Life for Roma in Greece a Year after 'Maria'". Open Society Foundations.org. 2014.10.17.

- ^ a b c d e (fr) Zlejko Jovanovic (30 October 2013). "Maria est rom, elle va donc redevenir invisible". Courrier international.com. ; translated from « Maria is Roma – so now she will become invisible once more », in The Guardian.com, 28–29 october 2013.

- ^ (fr) "Daniel Bonvoisin". Média Animation (in French). Retrieved 2016-08-24..

- ^ Thedrel, Arielle (2013-03-18). "Hongrie : Viktor Orban met l'extrême droite à l'honneur". Le Figaro.fr (in French). ISSN 0182-5852..

- ^ AFP (4 July 2013). "À Nice, Jean-Marie Le Pen dérape sur les Roms". Libération.fr..

- ^ a b Patrick McGuinness (17 November 2013). "Roms, le peuple des interstices". Libération.fr..

- ^ Ruus Dijksterhuis; Jana Hainsworth (24 July 2014). "Anti-Roma prejudice rampant in state child protection services". EU Observer..

- ^ a b Cree, Clapton and Smith 2016, abstract.

- ^ a b (fr) Giannis Mavris (12 February 2016). "Grèce : la petite Maria et les grands méchants médias". Cafébabel. Translated by Julien Rochard. translated from "Griechenland: Die kleine Maria und die bösen Medien" (in German). 18 January 2016.

- ^ a b Ryan Erfani-Ghettani (31 July 2014). "A global witch hunt! Media narratives, racial profiling and the Roma". Institute of Race Relations.org.uk..

- ^ Natasha Dukach (26 June 2015). "Media Promote Stereotypes Against Roma People". Fair Observer..

- ^ Thomas 2014, p. 2.

- ^ Thomas 2014, p. 87.

- ^ "Estrella Israel Garzón". Aula Intercultural (in European Spanish). Retrieved 2016-07-04..

- ^ (es) "Pomares Pastor, Ricardo Angel". cuentas.uv.es (in Valencian). University of Valencia. Retrieved 2016-07-04..

- ^ (es) Israel-Garzón and Pomares-Pastor 2015, p. 249.

- ^ a b c d e (es)Israel-Garzón and Pomares-Pastor 2015, p. 266.

- ^ a b c (es)Israel-Garzón and Pomares-Pastor 2015, p. 262.

- ^ (es)Israel-Garzón and Pomares-Pastor 2015, p. 263.

- ^ (es)Israel-Garzón and Pomares-Pastor 2015, p. 264.

- ^ (es)Israel-Garzón and Pomares-Pastor 2015, p. 265.

- ^ (es)Israel-Garzón and Pomares-Pastor 2015, p. 266-267.

- ^ (fr) Deleersnijder 2014, p. 105-106.

- ^ (fr) Condemi 2013, p. 22.

- ^ a b (fr) Emanuela Ignatoiu-Sora (24 October 2013). "Pourquoi les affaires des " anges blonds " réveillent malencontreusement les préjugés sur les Roms, voleurs d'enfants". Atlantico.

- ^ Doughty, Louise (2013-10-22). "An angel kidnapped by Gypsies? In the absence of all the facts, age-old libels are being replayed". The Guardian. Retrieved 2019-09-02.

- ^ a b (fr) Bordigoni and Piasere 2013, p. 22.

- ^ van Baar 2014, p. 30-31.

- ^ "Brooks, Ethel". womens-studies.rutgers.edu. Rutgers University. Retrieved 2016-07-05..

- ^ a b (fr) Brooks 2015, p. 117.

- ^ a b (fr) Brooks 2015, p. 116.

Appendix

[edit]Bibliography

[edit]Publications

[edit]- (fr) Amnesty International, "Nous réclamons justice": L'Europe doit protéger davantage les Roms contre les violences racistes, London, Amnesty International Publications, 2014, 42 p. (read online [archive] [PDF])

- (fr) Laurent Dejoie and Abdoulaye Harissou, Les Enfants fantômes, Albin Michel, 2014, 176 p. (ISBN 978-2-226-31335-5, read online [archive])

- (fr) Henri Deleersnijder, Democracies in peril: Europe faced with the drifts of national-populism, La Renaissance du livre, 2014, 186 p. (ISBN 978-2-507-00376-0, read online [archive])

- (fr) Nils Muižnieks (Commissioner for Human Rights), Annual activity report 2013, Council of Europe, 2014, 66 p. (read online [archive] [PDF])

- Emily Logan (Ombudsman for Children), Special Inquiry Report July 2014: Garda Síochána Act 2005 (Section 42) (Special Inquiries Relating to Garda Síochána) Order 2013, Dublin, Office of the Ombudsman for Children, 2014, 135 p. (read online [archive] [PDF])

- Yaron Matras, The Romani Gypsies, Harvard University Press, 2015, 336 p. (ISBN 978-0-674-74477-6, read online [archive]), pp. 197–198

- Krystal M. Thomas, The European Union and the Roma: The Production and Sustainability of Marginalization through Social Policy, Fairfax / Valletta, George Mason University / University of Malta, 2014, 118 p. (read online [archive] [PDF])

Articles and contributions

[edit]- (fr) Marc Bordigoni and Leonardo Piasere, "Qui sont les voleurs d'enfants?", Libération, November 3, 2013, p. 22 (read online [archive])

- (fr) Ethel Brooks, "Féminisme, communauté, résistance", Chimères, no 87, 2015, p. 114-122 (ISSN 0986-6035, read online [archive] Registration required, accessed July 4, 2016)

- (fr) Silvana Condemi, "Ange blond et noirs démons", Libération, November 3, 2013, p. 22 (read online [archive])

- Huub van Baar, "The Emergence of a Reasonable Anti-Gypsyism in Europe", in Timofey Agarin (editor), When Stereotype Meets Prejudice: Antiziganism in European Societies, Columbia University Press, 2014, 280 p. (ISBN 978-3-8382-6688-6, read online [archive]), p. 27-44 (online excerpt [archive])

- Dan Bilefsky, "Roma, Feared as Kidnappers, See Their Own Children at Risk", The New York Times, October 26, 2013, A1 (read online [archive])

- Viviene E. Cree, Gary Clapton and Mark Smith, "Standing up to complexity: researching moral panics in social work", European Journal of Social Work, vol. 19, 2016, pp. 354–367 (ISSN 1369-1457, doi:10.1080/13691457.2015.1084271, read online [archive], accessed May 24, 2016)

- Damian Le Bas, "Gypsies, Roma and Travellers – and Jews Too?", Jewish Quarterly, vol. 62, 2015, pp. 28–31 (ISSN 0449-010X, doi:10.1080/0449010X.2015.1010390, read online [archive], accessed September 1, 2016)

- (es) Estrella Israel-Garzón and Ricardo Ángel Pomares-Pastor, "Indicadores de calidad para analizar la información televisiva sobre grupos minoritarios. El caso de 'El ángel rubio'", Contratexto, no 24, 2015, pp. 249–269 (ISSN 1993-4904, read online [archive], accessed July 2, 2016)

See also

[edit]External links

[edit]- "Parents sought after child found in Roma camp in Greece" archive, 18 October 2013: call for witnesses launched by the "The Smile of the Child" association.

- "Yellow Notice (Public version): Girl – Greece – October 2013" archive [PDF], 20 October 2013: "yellow notice" issued by Interpol.