Topological insulator

This article reads like a scientific review article and potentially contains biased syntheses of primary sources. |

A topological insulator is a material whose interior behaves as an electrical insulator while its surface behaves as an electrical conductor,[3] meaning that electrons can only move along the surface of the material.

A topological insulator is an insulator for the same reason a "trivial" (ordinary) insulator is: there exists an energy gap between the valence and conduction bands of the material. But in a topological insulator, these bands are, in an informal sense, "twisted", relative to a trivial insulator.[4] The topological insulator cannot be continuously transformed into a trivial one without untwisting the bands, which closes the band gap and creates a conducting state. Thus, due to the continuity of the underlying field, the border of a topological insulator with a trivial insulator (including vacuum, which is topologically trivial) is forced to support a conducting state.[5]

Since this results from a global property of the topological insulator's band structure, local (symmetry-preserving) perturbations cannot damage this surface state.[6] This is unique to topological insulators: while ordinary insulators can also support conductive surface states, only the surface states of topological insulators have this robustness property.

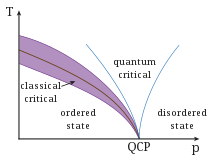

This leads to a more formal definition of a topological insulator: an insulator which cannot be adiabatically transformed into an ordinary insulator without passing through an intermediate conducting state.[5] In other words, topological insulators and trivial insulators are separate regions in the phase diagram, connected only by conducting phases. In this way, topological insulators provide an example of a state of matter not described by the Landau symmetry-breaking theory that defines ordinary states of matter.[6]

The properties of topological insulators and their surface states are highly dependent on both the dimension of the material and its underlying symmetries, and can be classified using the so-called periodic table of topological insulators. Some combinations of dimension and symmetries forbid topological insulators completely.[7] All topological insulators have at least U(1) symmetry from particle number conservation, and often have time-reversal symmetry from the absence of a magnetic field. In this way, topological insulators are an example of symmetry-protected topological order.[8] So-called "topological invariants", taking values in or , allow classification of insulators as trivial or topological, and can be computed by various methods.[7]

The surface states of topological insulators can have exotic properties. For example, in time-reversal symmetric 3D topological insulators, surface states have their spin locked at a right-angle to their momentum (spin-momentum locking). At a given energy the only other available electronic states have different spin, so "U"-turn scattering is strongly suppressed and conduction on the surface is highly metallic.

Despite their origin in quantum mechanical systems, analogues of topological insulators can also be found in classical media. There exist photonic,[9] magnetic,[10] and acoustic[11] topological insulators, among others.

Prediction

[edit]The first models of 3D topological insulators were proposed by B. A. Volkov and O. A. Pankratov in 1985,[12] and subsequently by Pankratov, S. V. Pakhomov, and Volkov in 1987.[13] Gapless 2D Dirac states were shown to exist at the band inversion contact in PbTe/SnTe[12] and HgTe/CdTe[13] heterostructures. Existence of interface Dirac states in HgTe/CdTe was experimentally verified by Laurens W. Molenkamp's group in 2D topological insulators in 2007.[14]

Later sets of theoretical models for the 2D topological insulator (also known as the quantum spin Hall insulators) were proposed by Charles L. Kane and Eugene J. Mele in 2005,[15] and also by B. Andrei Bernevig and Shoucheng Zhang in 2006.[16] The topological invariant was constructed and the importance of the time reversal symmetry was clarified in the work by Kane and Mele.[17] Subsequently, Bernevig, Taylor L. Hughes and Zhang made a theoretical prediction that 2D topological insulator with one-dimensional (1D) helical edge states would be realized in quantum wells (very thin layers) of mercury telluride sandwiched between cadmium telluride.[18] The transport due to 1D helical edge states was indeed observed in the experiments by Molenkamp's group in 2007.[14]

Although the topological classification and the importance of time-reversal symmetry was pointed in the 2000s, all the necessary ingredients and physics of topological insulators were already understood in the works from the 1980s.

In 2007, it was predicted that 3D topological insulators might be found in binary compounds involving bismuth,[19][20][21][22] and in particular "strong topological insulators" exist that cannot be reduced to multiple copies of the quantum spin Hall state.[23]

Experimental realization

[edit]2D Topological insulators were first realized in system containing HgTe quantum wells sandwiched between cadmium telluride in 2007.

The first 3D topological insulator to be realized experimentally was Bi1 − x Sb x.[24][25][26] Bismuth in its pure state, is a semimetal with a small electronic band gap. Using angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy, and many other measurements, it was observed that Bi1 − xSbx alloy exhibits an odd surface state (SS) crossing between any pair of Kramers points and the bulk features massive Dirac fermions.[25] Additionally, bulk Bi1 − xSbx has been predicted to have 3D Dirac particles.[27] This prediction is of particular interest due to the observation of charge quantum Hall fractionalization in 2D graphene[28] and pure bismuth.[29]

Shortly thereafter symmetry-protected surface states were also observed in pure antimony, bismuth selenide, bismuth telluride and antimony telluride using angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (ARPES).[30][31][32][33][34] and bismuth selenide.[34][35] Many semiconductors within the large family of Heusler materials are now believed to exhibit topological surface states.[36][37] In some of these materials, the Fermi level actually falls in either the conduction or valence bands due to naturally-occurring defects, and must be pushed into the bulk gap by doping or gating.[38][39] The surface states of a 3D topological insulator is a new type of two-dimensional electron gas (2DEG) where the electron's spin is locked to its linear momentum.[31]

Fully bulk-insulating or intrinsic 3D topological insulator states exist in Bi-based materials as demonstrated in surface transport measurements.[40] In a new Bi based chalcogenide (Bi1.1Sb0.9Te2S) with slightly Sn - doping, exhibits an intrinsic semiconductor behavior with Fermi energy and Dirac point lie in the bulk gap and the surface states were probed by the charge transport experiments.[41]

It was proposed in 2008 and 2009 that topological insulators are best understood not as surface conductors per se, but as bulk 3D magnetoelectrics with a quantized magnetoelectric effect.[42][43] This can be revealed by placing topological insulators in magnetic field. The effect can be described in language similar to that of the hypothetical axion particle of particle physics.[44] The effect was reported by researchers at Johns Hopkins University and Rutgers University using THz spectroscopy who showed that the Faraday rotation was quantized by the fine structure constant.[45]

In 2012, topological Kondo insulators were identified in samarium hexaboride, which is a bulk insulator at low temperatures.[46][47]

In 2014, it was shown that magnetic components, like the ones in spin-torque computer memory, can be manipulated by topological insulators.[48][49] The effect is related to metal–insulator transitions (Bose–Hubbard model).[citation needed]

Floquet topological insulators

[edit]Topological insulators are challenging to synthesize, and limited in topological phases accessible with solid-state materials.[50] This has motivated the search for topological phases on the systems that simulate the same principles underlying topological insulators. Discrete time quantum walks (DTQW) have been proposed for making Floquet topological insulators (FTI). This periodically driven system simulates an effective (Floquet) Hamiltonian that is topologically nontrivial.[51] This system replicates the effective Hamiltonians from all universal classes of 1- to 3-D topological insulators.[52][53][54][55] Interestingly, topological properties of Floquet topological insulators could be controlled via an external periodic drive rather than an external magnetic field. An atomic lattice empowered by distance selective Rydberg interaction could simulate different classes of FTI over a couple of hundred sites and steps in 1, 2 or 3 dimensions.[55] The long-range interaction allows designing topologically ordered periodic boundary conditions, further enriching the realizable topological phases.[55]

Properties and applications

[edit]Spin-momentum locking[31] in the topological insulator allows symmetry-protected surface states to host Majorana particles if superconductivity is induced on the surface of 3D topological insulators via proximity effects.[56] (Note that Majorana zero-mode can also appear without topological insulators.[57]) The non-trivialness of topological insulators is encoded in the existence of a gas of helical Dirac fermions. Dirac particles which behave like massless relativistic fermions have been observed in 3D topological insulators. Note that the gapless surface states of topological insulators differ from those in the quantum Hall effect: the gapless surface states of topological insulators are symmetry-protected (i.e., not topological), while the gapless surface states in quantum Hall effect are topological (i.e., robust against any local perturbations that can break all the symmetries). The topological invariants cannot be measured using traditional transport methods, such as spin Hall conductance, and the transport is not quantized by the invariants. An experimental method to measure topological invariants was demonstrated which provide a measure of the topological order.[58] (Note that the term topological order has also been used to describe the topological order with emergent gauge theory discovered in 1991.[59][60]) More generally (in what is known as the ten-fold way) for each spatial dimensionality, each of the ten Altland—Zirnbauer symmetry classes of random Hamiltonians labelled by the type of discrete symmetry (time-reversal symmetry, particle-hole symmetry, and chiral symmetry) has a corresponding group of topological invariants (either , or trivial) as described by the periodic table of topological invariants.[61]

The most promising applications of topological insulators are spintronic devices and dissipationless transistors for quantum computers based on the quantum Hall effect[14] and quantum anomalous Hall effect.[62] In addition, topological insulator materials have also found practical applications in advanced magnetoelectronic and optoelectronic devices.[63][64]

Thermoelectrics

[edit]Some of the most well-known topological insulators are also thermoelectric materials, such as Bi2Te3 and its alloys with Bi2Se3 (n-type thermoelectrics) and Sb2Te3 (p-type thermoelectrics).[65] High thermoelectric power conversion efficiency is realized in materials with low thermal conductivity, high electrical conductivity, and high Seebeck coefficient (i.e., the incremental change in voltage due to an incremental change in temperature). Topological insulators are often composed of heavy atoms, which tends to lower thermal conductivity and are therefore beneficial for thermoelectrics. A recent study also showed that good electrical characteristics (i.e., high electrical conductivity and Seebeck coefficient) can arise in topological insulators due to warping of the bulk band structure, which is driven by band inversion.[66] Often, the electrical conductivity and Seebeck coefficient are conflicting properties of thermoelectrics and difficult to optimize simultaneously. Band warping, induced by band inversion in a topological insulator, can mediate the two properties by reducing the effective mass of electrons/holes and increasing the valley degeneracy (i.e., the number of electronic bands that are contributing to charge transport). As a result, topological insulators are generally interesting candidates for thermoelectric applications.

Synthesis

[edit]Topological insulators can be grown using different methods such as metal-organic chemical vapor deposition (MOCVD),[67]

physical vapor deposition (PVD),[68] solvothermal synthesis,[69] sonochemical technique[70] and molecular beam epitaxy

(MBE).[34] MBE has so far been the most common experimental technique. The growth of thin film topological insulators is governed by weak van der Waals interactions.[71] The weak interaction allows to exfoliate the thin film from bulk crystal with a clean and perfect surface. The van der Waals interactions in epitaxy also known as van der Waals epitaxy (VDWE), is a phenomenon governed by weak van der Waals interactions between layered materials of different or same elements[72] in which the materials are stacked on top of each other. This approach allows the growth of layered topological insulators on other substrates for heterostructure and integrated circuits.[72]

MBE growth of topological insulators

Molecular beam epitaxy (MBE) is an epitaxy method for the growth of a crystalline material on a crystalline substrate to form an ordered layer. MBE is performed in high vacuum or ultra-high vacuum, the elements are heated in different electron beam evaporators until they sublime. The gaseous elements then condense on the wafer where they react with each other to form single crystals.

MBE is an appropriate technique for the growth of high quality single-crystal films. In order to avoid a huge lattice mismatch and defects at the interface, the substrate and thin film are expected to have similar lattice constants. MBE has an advantage over other methods due to the fact that the synthesis is performed in high vacuum hence resulting in less contamination. Additionally, lattice defect is reduced due to the ability to influence the growth rate and the ratio of species of source materials present at the substrate interface.[73] Furthermore, in MBE, samples can be grown layer by layer which results in flat surfaces with smooth interface for engineered heterostructures. Moreover, MBE synthesis technique benefits from the ease of moving a topological insulator sample from the growth chamber to a characterization chamber such as angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (ARPES) or scanning tunneling microscopy (STM) studies.[74]

Due to the weak van der Waals bonding, which relaxes the lattice-matching condition, TI can be grown on a wide variety of substrates[75] such as Si(111),[76][77] Al

2O

3, GaAs(111),[78]

InP(111), CdS(0001) and Y

3Fe

5O

12 .

PVD growth of topological insulators

[edit]The physical vapor deposition (PVD) technique does not suffer from the disadvantages of the exfoliation method and, at the same time, it is much simpler and cheaper than the fully controlled growth by molecular-beam epitaxy. The PVD method enables a reproducible synthesis of single crystals of various layered quasi-two-dimensional materials including topological insulators (i.e., Bi

2Se

3, Bi

2Te

3).[79] The resulted single crystals have a well-defined crystallographic orientation; their composition, thickness, size, and the surface density on the desired substrate can be controlled.

The thickness control is particularly important for 3D TIs in which the trivial (bulky) electronic channels usually dominate the transport properties and mask the response of the topological (surface) modes. By reducing the thickness, one lowers the contribution of trivial bulk channels into the total conduction, thus forcing the topological modes to carry the electric current.[80]

Bismuth-based topological insulators

[edit]Thus far, the field of topological insulators has been focused on bismuth and antimony chalcogenide based materials such as Bi

2Se

3, Bi

2Te

3, Sb

2Te

3 or Bi1 − xSbx, Bi1.1Sb0.9Te2S.[41] The choice of chalcogenides is related to the van der Waals relaxation of the lattice matching strength which restricts the number of materials and substrates.[73] Bismuth chalcogenides have been studied extensively for TIs and their applications in thermoelectric materials. The van der Waals interaction in TIs exhibit important features due to low surface energy. For instance, the surface of Bi

2Te

3 is usually terminated by Te due to its low surface energy.[34]

Bismuth chalcogenides have been successfully grown on different substrates. In particular, Si has been a good substrate for the successful growth of Bi

2Te

3 . However, the use of sapphire as substrate has not been so encouraging due to a large mismatch of about 15%.[81] The selection of appropriate substrate can improve the overall properties of TI. The use of buffer layer can reduce the lattice match hence improving the electrical properties of TI.[81] Bi

2Se

3 can be grown on top of various Bi2 − xInxSe3 buffers. Table 1 shows Bi

2Se

3, Bi

2Te

3, Sb

2Te

3 on different substrates and the resulting lattice mismatch. Generally, regardless of the substrate used, the resulting films have a textured surface that is characterized by pyramidal single-crystal domains with quintuple-layer steps. The size and relative proportion of these pyramidal domains vary with factors that include film thickness, lattice mismatch with the substrate and interfacial chemistry-dependent film nucleation. The synthesis of thin films have the stoichiometry problem due to the high vapor pressures of the elements. Thus, binary tetradymites are extrinsically doped as n-type (Bi

2Se

3, Bi

2Te

3 ) or p-type (Sb

2Te

3 ).[73] Due to the weak van der Waals bonding, graphene is one of the preferred substrates for TI growth despite the large lattice mismatch.

| Substrate | Bi 2Se 3 % |

Bi 2Te 3 % |

Sb 2Te 3 % |

|---|---|---|---|

| graphene | −40.6 | −43.8 | −42.3 |

| Si | −7.3 | −12.3 | −9.7 |

| CaF 2 |

−6.8 | −11.9 | −9.2 |

| GaAs | −3.4 | −8.7 | −5.9 |

| CdS | −0.2 | −5.7 | −2.8 |

| InP | 0.2 | −5.3 | −2.3 |

| BaF 2 |

5.9 | 0.1 | 2.8 |

| CdTe | 10.7 | 4.6 | 7.8 |

| Al 2O 3 |

14.9 | 8.7 | 12.0 |

| SiO 2 |

18.6 | 12.1 | 15.5 |

Identification

[edit]The first step of topological insulators identification takes place right after synthesis, meaning without breaking the vacuum and moving the sample to an atmosphere. That could be done by using angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (ARPES) or scanning tunneling microscopy (STM) techniques.[74] Further measurements includes structural and chemical probes such as X-ray diffraction and energy-dispersive spectroscopy but depending on the sample quality, the lack of sensitivity could remain. Transport measurements cannot uniquely pinpoint the topology by definition of the state.

Classification

[edit]Bloch's theorem allows a full characterization of the wave propagation properties of a material by assigning a matrix to each wave vector in the Brillouin zone.

Mathematically, this assignment creates a vector bundle. Different materials will have different wave propagation properties, and thus different vector bundles. If we consider all insulators (materials with a band gap), this creates a space of vector bundles. It is the topology of this space (modulo trivial bands) from which the "topology" in topological insulators arises.[7]

Specifically, the number of connected components of the space indicates how many different "islands" of insulators exist amongst the metallic states. Insulators in the connected component containing the vacuum state are identified as "trivial", and all other insulators as "topological". The connected component in which an insulator lies can be identified with a number, referred to as a "topological invariant".[7]

This space can be restricted under the presence of symmetries, changing the resulting topology. Although unitary symmetries are usually significant in quantum mechanics, they have no effect on the topology here.[82] Instead, the three symmetries typically considered are time-reversal symmetry, particle-hole symmetry, and chiral symmetry (also called sublattice symmetry). Mathematically, these are represented as, respectively: an anti-unitary operator which commutes with the Hamiltonian; an anti-unitary operator which anti-commutes with the Hamiltonian; and a unitary operator which anti-commutes with the Hamiltonian. All combinations of the three together with each spatial dimension result in the so-called periodic table of topological insulators.[7]

Future developments

[edit]The field of topological insulators still needs to be developed. The best bismuth chalcogenide topological insulators have about 10 meV bandgap variation due to the charge. Further development should focus on the examination of both: the presence of high-symmetry electronic bands and simply synthesized materials. One of the candidates is half-Heusler compounds.[74] These crystal structures can consist of a large number of elements. Band structures and energy gaps are very sensitive to the valence configuration; because of the increased likelihood of intersite exchange and disorder, they are also very sensitive to specific crystalline configurations. A nontrivial band structure that exhibits band ordering analogous to that of the known 2D and 3D TI materials was predicted in a variety of 18-electron half-Heusler compounds using first-principles calculations.[83] These materials have not yet shown any sign of intrinsic topological insulator behavior in actual experiments.

See also

[edit]- Topological order

- Topological quantum computer

- Topological quantum field theory

- Topological quantum number

- Quantum Hall effect

- Quantum spin Hall effect

- Periodic table of topological invariants

- Bismuth selenide

- Photonic topological insulator

References

[edit]- ^ Moore, Joel E. (2010). "The birth of topological insulators". Nature. 464 (7286): 194–198. Bibcode:2010Natur.464..194M. doi:10.1038/nature08916. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 20220837. S2CID 1911343.

- ^ Hasan, M.Z.; Moore, J.E. (2011). "Three-Dimensional Topological Insulators". Annual Review of Condensed Matter Physics. 2: 55–78. arXiv:1011.5462. Bibcode:2011ARCMP...2...55H. doi:10.1146/annurev-conmatphys-062910-140432. S2CID 11516573.

- ^ Kane, C. L.; Mele, E. J. (2005). "Z2 Topological Order and the Quantum Spin Hall Effect". Physical Review Letters. 95 (14): 146802. arXiv:cond-mat/0506581. Bibcode:2005PhRvL..95n6802K. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.95.146802. PMID 16241681. S2CID 1775498.

- ^ Zhu, Zhiyong; Cheng, Yingchun; Schwingenschlögl, Udo (2012-06-01). "Band inversion mechanism in topological insulators: A guideline for materials design". Physical Review B. 85 (23): 235401. Bibcode:2012PhRvB..85w5401Z. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.85.235401. hdl:10754/315777. ISSN 1098-0121.

- ^ a b Qi, Xiao-Liang; Zhang, Shou-Cheng (2011-10-14). "Topological insulators and superconductors". Reviews of Modern Physics. 83 (4): 1057–1110. arXiv:1008.2026. Bibcode:2011RvMP...83.1057Q. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.83.1057. ISSN 0034-6861. S2CID 118373714.

- ^ a b Hasan, M. Z.; Kane, C. L. (2010-11-08). "Colloquium: Topological insulators". Reviews of Modern Physics. 82 (4): 3045–3067. arXiv:1002.3895. Bibcode:2010RvMP...82.3045H. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.82.3045. S2CID 16066223.

- ^ a b c d e Kitaev, Alexei (2009-05-14). "Periodic table for topological insulators and superconductors". AIP Conference Proceedings. 1134 (1): 22–30. arXiv:0901.2686. Bibcode:2009AIPC.1134...22K. doi:10.1063/1.3149495. ISSN 0094-243X. S2CID 14320124.

- ^ Senthil, T. (2015-03-01). "Symmetry-Protected Topological Phases of Quantum Matter". Annual Review of Condensed Matter Physics. 6 (1): 299–324. arXiv:1405.4015. Bibcode:2015ARCMP...6..299S. doi:10.1146/annurev-conmatphys-031214-014740. ISSN 1947-5454. S2CID 12669555.

- ^ Khanikaev, Alexander B.; Hossein Mousavi, S.; Tse, Wang-Kong; Kargarian, Mehdi; MacDonald, Allan H.; Shvets, Gennady (March 2013). "Photonic topological insulators". Nature Materials. 12 (3): 233–239. arXiv:1204.5700. Bibcode:2013NatMa..12..233K. doi:10.1038/nmat3520. ISSN 1476-4660. PMID 23241532. S2CID 39748656.

- ^ Tokura, Yoshinori; Yasuda, Kenji; Tsukazaki, Atsushi (February 2019). "Magnetic topological insulators". Nature Reviews Physics. 1 (2): 126–143. Bibcode:2019NatRP...1..126T. doi:10.1038/s42254-018-0011-5. ISSN 2522-5820. S2CID 53694955.

- ^ He, Cheng; Ni, Xu; Ge, Hao; Sun, Xiao-Chen; Chen, Yan-Bin; Lu, Ming-Hui; Liu, Xiao-Ping; Chen, Yan-Feng (December 2016). "Acoustic topological insulator and robust one-way sound transport". Nature Physics. 12 (12): 1124–1129. arXiv:1512.03273. Bibcode:2016NatPh..12.1124H. doi:10.1038/nphys3867. ISSN 1745-2473. S2CID 119255437.

- ^ a b Volkov, B. A.; Pankratov, O. A. (1985-08-25). "Two-dimensional massless electrons in an inverted contact". JETP Letters. 42 (4): 178–181.

- ^ a b Pankratov, O. A.; Pakhomov, S. V.; Volkov, B. A. (1987-01-01). "Supersymmetry in heterojunctions: Band-inverting contact on the basis of Pb1-xSnxTe and Hg1-xCdxTe". Solid State Communications. 61 (2): 93–96. Bibcode:1987SSCom..61...93P. doi:10.1016/0038-1098(87)90934-3. ISSN 0038-1098.

- ^ a b c König, Markus; Wiedmann, Steffen; Brüne, Christoph; Roth, Andreas; Buhmann, Hartmut; Molenkamp, Laurens W.; Qi, Xiao-Liang; Zhang, Shou-Cheng (2007-11-02). "Quantum Spin Hall Insulator State in HgTe Quantum Wells". Science. 318 (5851): 766–770. arXiv:0710.0582. Bibcode:2007Sci...318..766K. doi:10.1126/science.1148047. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 17885096. S2CID 8836690.

- ^ Kane, C. L.; Mele, E. J. (2005-11-23). "Quantum Spin Hall Effect in Graphene". Physical Review Letters. 95 (22): 226801. arXiv:cond-mat/0411737. Bibcode:2005PhRvL..95v6801K. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.95.226801. PMID 16384250. S2CID 6080059.

- ^ Bernevig, B. Andrei; Zhang, Shou-Cheng (2006-03-14). "Quantum Spin Hall Effect". Physical Review Letters. 96 (10): 106802. arXiv:cond-mat/0504147. Bibcode:2006PhRvL..96j6802B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.96.106802. PMID 16605772. S2CID 2618285.

- ^ Kane, C. L.; Mele, E. J. (2005-09-28). "${Z}_{2}$ Topological Order and the Quantum Spin Hall Effect". Physical Review Letters. 95 (14): 146802. arXiv:cond-mat/0506581. Bibcode:2005PhRvL..95n6802K. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.95.146802. PMID 16241681. S2CID 1775498.

- ^ Bernevig, B. Andrei; Hughes, Taylor L.; Zhang, Shou-Cheng (2006-12-15). "Quantum Spin Hall Effect and Topological Phase Transition in HgTe Quantum Wells". Science. 314 (5806): 1757–1761. arXiv:cond-mat/0611399. Bibcode:2006Sci...314.1757B. doi:10.1126/science.1133734. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 17170299. S2CID 7295726.

- ^ Roy, Rahul (2009-05-21). "Three dimensional topological invariants for time reversal invariant Hamiltonians and the three dimensional quantum spin Hall effect". Physical Review B. 79: 195322. arXiv:cond-mat/0607531. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.79.195322. S2CID 119407081.

- ^ Liang Fu; C. L. Kane; E. J. Mele (2007-03-07). "Topological insulators in three dimensions". Physical Review Letters. 98 (10): 106803. arXiv:cond-mat/0607699. Bibcode:2007PhRvL..98j6803F. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.98.106803. PMID 17358555. S2CID 6037351.

- ^ Fu, Liang; C. L. Kane (2007-07-02). "Topological insulators with inversion symmetry". Physical Review B. 76 (4): 045302. arXiv:cond-mat/0611341. Bibcode:2007PhRvB..76d5302F. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.76.045302. S2CID 15011491.

- ^ Shuichi Murakami (2007). "Phase transition between the quantum spin Hall and insulator phases in 3D: emergence of a topological gapless phase". New Journal of Physics. 9 (9): 356. arXiv:0710.0930. Bibcode:2007NJPh....9..356M. doi:10.1088/1367-2630/9/9/356. ISSN 1367-2630. S2CID 13999448.

- ^ Kane, C. L.; Moore, J. E. (2011). "Topological Insulators" (PDF). Physics World. 24 (2): 32–36. Bibcode:2011PhyW...24b..32K. doi:10.1088/2058-7058/24/02/36.

- ^ Fu, Liang; Kane, C. L. (2007-07-02). "Topological insulators with inversion symmetry". Physical Review B. 76 (4): 045302. arXiv:cond-mat/0611341. Bibcode:2007PhRvB..76d5302F. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.76.045302. S2CID 15011491.

- ^ a b Hasan, M. Zahid; Moore, Joel E. (2011). "Three-Dimensional Topological Insulators". Annual Review of Condensed Matter Physics. 2 (1): 55–78. arXiv:1011.5462. Bibcode:2011ARCMP...2...55H. doi:10.1146/annurev-conmatphys-062910-140432. ISSN 1947-5454. S2CID 11516573.

- ^ Hsieh, David; Dong Qian; Andrew L. Wray; Yuqi Xia; Yusan Hor; Robert Cava; M. Zahid Hasan (2008). "A Topological Dirac insulator in a quantum spin Hall phase". Nature. 452 (9): 970–4. arXiv:0902.1356. Bibcode:2008Natur.452..970H. doi:10.1038/nature06843. PMID 18432240. S2CID 4402113.

- ^ Buot, F. A. (1973-09-01). "Weyl Transform and the Magnetic Susceptibility of a Relativistic Dirac Electron Gas". Physical Review A. 8 (3): 1570–81. Bibcode:1973PhRvA...8.1570B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.8.1570.

- ^ Kane, C. L.; Mele, E. J. (2005-11-23). "Quantum Spin Hall Effect in Graphene". Physical Review Letters. 95 (22): 226801. arXiv:cond-mat/0411737. Bibcode:2005PhRvL..95v6801K. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.95.226801. PMID 16384250. S2CID 6080059.

- ^ Behnia, Kamran; Balicas, Luis; Kopelevich, Yakov (2007-09-21). "Signatures of Electron Fractionalization in Ultraquantum Bismuth". Science. 317 (5845): 1729–31. arXiv:0802.1993. Bibcode:2007Sci...317.1729B. doi:10.1126/science.1146509. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 17702909. S2CID 15306515.

- ^ Hasan, M. Zahid; Kane, Charles L. (2010). "Topological Insulators". Reviews of Modern Physics. 82 (4): 3045–67. arXiv:1002.3895. Bibcode:2010RvMP...82.3045H. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.82.3045. S2CID 16066223.

- ^ a b c Hsieh, D.; Xia, Y.; Qian, D.; Wray, L.; et al. (2009). "A tunable topological insulator in the spin helical Dirac transport regime". Nature. 460 (7259): 1101–5. arXiv:1001.1590. Bibcode:2009Natur.460.1101H. doi:10.1038/nature08234. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 19620959. S2CID 4369601.

- ^ Hsieh, D.; Xia, Y.; Wray, L.; Qian, D.; Pal, A.; Dil, J. H.; Osterwalder, J.; Meier, F.; Bihlmayer, G.; Kane, C. L.; et al. (2009). "Observation of Unconventional Quantum Spin Textures in Topological Insulators". Science. 323 (5916): 919–922. arXiv:0902.2617. Bibcode:2009Sci...323..919H. doi:10.1126/science.1167733. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 19213915. S2CID 118353248.

- ^ Hasan, M. Zahid; Xu, Su-Yang; Neupane, Madhab (2015), "Topological Insulators, Topological Dirac semimetals, Topological Crystalline Insulators, and Topological Kondo Insulators", Topological Insulators, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, pp. 55–100, doi:10.1002/9783527681594.ch4, ISBN 978-3-527-68159-4

- ^ a b c d Chen, Xi; Ma, Xu-Cun; He, Ke; Jia, Jin-Feng; Xue, Qi-Kun (2011-03-01). "Molecular Beam Epitaxial Growth of Topological Insulators". Advanced Materials. 23 (9): 1162–5. Bibcode:2011AdM....23.1162C. doi:10.1002/adma.201003855. ISSN 0935-9648. PMID 21360770. S2CID 33855507.

- ^ Chiatti, Olivio; Riha, Christian; Lawrenz, Dominic; Busch, Marco; Dusari, Srujana; Sánchez-Barriga, Jaime; Mogilatenko, Anna; Yashina, Lada V.; Valencia, Sergio (2016-06-07). "2D layered transport properties from topological insulator Bi

2Se

3 single crystals and micro flakes". Scientific Reports. 6 (1): 27483. arXiv:1512.01442. Bibcode:2016NatSR...627483C. doi:10.1038/srep27483. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 4895388. PMID 27270569. - ^ Chadov, Stanislav; Xiao-Liang Qi; Jürgen Kübler; Gerhard H. Fecher; Claudia Felser; Shou-Cheng Zhang (July 2010). "Tunable multifunctional topological insulators in ternary Heusler compounds". Nature Materials. 9 (7): 541–5. arXiv:1003.0193. Bibcode:2010NatMa...9..541C. doi:10.1038/nmat2770. PMID 20512154. S2CID 32178219.

- ^ Lin, Hsin; L. Andrew Wray; Yuqi Xia; Suyang Xu; Shuang Jia; Robert J. Cava; Arun Bansil; M. Zahid Hasan (July 2010). "Half-Heusler ternary compounds as new multifunctional experimental platforms for topological quantum phenomena". Nat Mater. 9 (7): 546–9. arXiv:1003.0155. Bibcode:2010NatMa...9..546L. doi:10.1038/nmat2771. ISSN 1476-1122. PMID 20512153.

- ^ Hsieh, D.; Y. Xia; D. Qian; L. Wray; F. Meier; J. H. Dil; J. Osterwalder; L. Patthey; A. V. Fedorov; H. Lin; A. Bansil; D. Grauer; Y. S. Hor; R. J. Cava; M. Z. Hasan (2009). "Observation of Time-Reversal-Protected Single-Dirac-Cone Topological-Insulator States in Bi

2Te

3 and Sb

2Te

3". Physical Review Letters. 103 (14): 146401. Bibcode:2009PhRvL.103n6401H. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.103.146401. PMID 19905585. - ^ Noh, H.-J.; H. Koh; S.-J. Oh; J.-H. Park; H.-D. Kim; J. D. Rameau; T. Valla; T. E. Kidd; P. D. Johnson; Y. Hu; Q. Li (2008). "Spin-orbit interaction effect in the electronic structure of Bi

2Te

3 observed by angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy". EPL. 81 (5): 57006. arXiv:0803.0052. Bibcode:2008EL.....8157006N. doi:10.1209/0295-5075/81/57006. S2CID 9282408. - ^ Xu, Y; Miotkowski, I.; Liu, C.; Tian, J.; Nam, H.; Alidoust, N.; Hu, J.; Shih, C.-K; Hasan, M.Z.; Chen, Y.-P. (2014). "Observation of topological surface state quantum Hall effect in an intrinsic three-dimensional topological insulator". Nature Physics. 10 (12): 956–963. arXiv:1409.3778. Bibcode:2014NatPh..10..956X. doi:10.1038/nphys3140. S2CID 51843826.

- ^ a b Kushwaha, S. K.; Pletikosić, I.; Liang, T.; et al. (2015). "Sn-doped Bi1.1Sb0.9Te2S bulk crystal topological insulator with excellent properties". Nature Communications. 7: 11456. arXiv:1508.03655. doi:10.1038/ncomms11456. PMC 4853473. PMID 27118032.

- ^ Qi, Xiao-Liang; Hughes, Taylor L.; Zhang, Shou-Cheng (2008-11-24). "Topological field theory of time-reversal invariant insulators". Physical Review B. 78 (19). American Physical Society (APS): 195424. arXiv:0802.3537. Bibcode:2008PhRvB..78s5424Q. doi:10.1103/physrevb.78.195424. ISSN 1098-0121. S2CID 117659977.

- ^ Essin, Andrew M.; Moore, Joel E.; Vanderbilt, David (2009-04-10). "Magnetoelectric Polarizability and Axion Electrodynamics in Crystalline Insulators". Physical Review Letters. 102 (14): 146805. arXiv:0810.2998. Bibcode:2009PhRvL.102n6805E. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.102.146805. ISSN 0031-9007. PMID 19392469. S2CID 1133717.

- ^ Wilczek, Frank (1987-05-04). "Two applications of axion electrodynamics". Physical Review Letters. 58 (18). American Physical Society (APS): 1799–1802. Bibcode:1987PhRvL..58.1799W. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.58.1799. ISSN 0031-9007. PMID 10034541.

- ^ Wu, Liang; Salehi, M.; Koirala, N.; Moon, J.; Oh, S.; Armitage, N. P. (2016). "Quantized Faraday and Kerr rotation and axion electrodynamics of a 3D topological insulator". Science. 354 (6316): 1124–7. arXiv:1603.04317. Bibcode:2016Sci...354.1124W. doi:10.1126/science.aaf5541. PMID 27934759.

- ^ Samuel Reich, Eugenie (2012). "Hopes surface for exotic insulator: Findings by three teams may solve a 40-year-old mystery". Nature. 492 (7428). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 165. Bibcode:2012Natur.492..165S. doi:10.1038/492165a. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 23235853.

- ^ Dzero, Maxim; Sun, Kai; Galitski, Victor; Coleman, Piers (2010-03-12). "Topological Kondo Insulators". Physical Review Letters. 104 (10): 106408. arXiv:0912.3750. Bibcode:2010PhRvL.104j6408D. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.104.106408. ISSN 0031-9007. PMID 20366446. S2CID 119270507.

- ^ "Weird materials could make faster computers". Science News. Retrieved 2014-07-23.

- ^ Mellnik, A. R; Lee, J. S; Richardella, A; Grab, J. L; Mintun, P. J; Fischer, M. H; Vaezi, A; Manchon, A; Kim, E. -A; Samarth, N; Ralph, D. C (2014). "Spin-transfer torque generated by a topological insulator". Nature. 511 (7510): 449–451. arXiv:1402.1124. Bibcode:2014Natur.511..449M. doi:10.1038/nature13534. PMID 25056062. S2CID 205239604.

- ^ Ando, Yoichi (2013-10-15). "Topological Insulator Materials". Journal of the Physical Society of Japan. 82 (10): 102001. arXiv:1304.5693. Bibcode:2013JPSJ...82j2001A. doi:10.7566/jpsj.82.102001. ISSN 0031-9015. S2CID 55912821.

- ^ Cayssol, Jérôme; Dóra, Balázs; Simon, Ferenc; Moessner, Roderich (2013-01-28). "Floquet topological insulators". Physica Status Solidi RRL. 7 (1–2): 101–108. arXiv:1211.5623. Bibcode:2013PSSRR...7..101C. doi:10.1002/pssr.201206451. ISSN 1862-6254. S2CID 52082807.

- ^ Kitaev, Alexei; Lebedev, Vladimir; Feigel'man, Mikhail (2009). "Periodic table for topological insulators and superconductors". AIP Conference Proceedings. 1134 (1). AIP: 22–30. arXiv:0901.2686. Bibcode:2009AIPC.1134...22K. doi:10.1063/1.3149495. S2CID 14320124.

- ^ Panahiyan, S.; Fritzsche, S. (2021-01-05). "Toward simulation of topological phenomena with one-, two-, and three-dimensional quantum walks". Physical Review A. 103 (1): 012201. arXiv:2005.08720. Bibcode:2021PhRvA.103a2201P. doi:10.1103/physreva.103.012201. ISSN 2469-9926. S2CID 218674364.

- ^ Kitagawa, Takuya; Rudner, Mark S.; Berg, Erez; Demler, Eugene (2010-09-24). "Exploring topological phases with quantum walks". Physical Review A. 82 (3): 033429. arXiv:1003.1729. Bibcode:2010PhRvA..82c3429K. doi:10.1103/physreva.82.033429. ISSN 1050-2947. S2CID 21800060.

- ^ a b c Khazali, Mohammadsadegh (2022-03-03). "Discrete-Time Quantum-Walk & Floquet Topological Insulators via Distance-Selective Rydberg-Interaction". Quantum. 6: 664. arXiv:2101.11412. Bibcode:2022Quant...6..664K. doi:10.22331/q-2022-03-03-664. S2CID 246635019.

- ^ Fu, L.; C. L. Kane (2008). "Superconducting Proximity Effect and Majorana Fermions at the Surface of a Topological Insulator". Phys. Rev. Lett. 100 (9): 096407. arXiv:0707.1692. Bibcode:2008PhRvL.100i6407F. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.096407. PMID 18352737. S2CID 7618062.

- ^ Potter, Andrew C.; Lee, Patrick A. (23 March 2012). "Topological superconductivity and Majorana fermions in metallic surface states". Physical Review B. 85 (9): 094516. arXiv:1201.2176. Bibcode:2012PhRvB..85i4516P. doi:10.1103/physrevb.85.094516. ISSN 1098-0121. S2CID 59462024.

- ^ Hsieh, D.; D. Hsieh; Y. Xia; L. Wray; D. Qian; A. Pal; J. H. Dil; F. Meier; J. Osterwalder; C. L. Kane; G. Bihlmayer; Y. S. Hor; R. J. Cava; M. Z. Hasan (2009). "Observation of Unconventional Quantum Spin Textures in Topological Insulators". Science. 323 (5916): 919–922. arXiv:0902.2617. Bibcode:2009Sci...323..919H. doi:10.1126/science.1167733. PMID 19213915. S2CID 118353248.

- ^ Read, N.; Sachdev, Subir (1991). "Large-N expansion for frustrated quantum antiferromagnets". Phys. Rev. Lett. 66 (13): 1773–6. Bibcode:1991PhRvL..66.1773R. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.66.1773. PMID 10043303.

- ^ Wen, Xiao-Gang (1991). "Mean Field Theory of Spin Liquid States with Finite Energy Gaps". Phys. Rev. B. 44 (6): 2664–2672. Bibcode:1991PhRvB..44.2664W. doi:10.1103/physrevb.44.2664. PMID 9999836.

- ^ Chiu, C.; J. Teo; A. Schnyder; S. Ryu (2016). "Classification of topological quantum matter with symmetries". Rev. Mod. Phys. 88 (35005): 035005. arXiv:1505.03535. Bibcode:2016RvMP...88c5005C. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.88.035005. S2CID 119294876.

- ^ Chang, Cui-Zu; Zhang, Jinsong; Feng, Xiao; Shen, Jie; Zhang, Zuocheng; Guo, Minghua; Li, Kang; Ou, Yunbo; Wei, Pang (2013-04-12). "Experimental Observation of the Quantum Anomalous Hall Effect in a Magnetic Topological Insulator". Science. 340 (6129): 167–170. arXiv:1605.08829. Bibcode:2013Sci...340..167C. doi:10.1126/science.1234414. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 23493424. S2CID 29455044.

- ^ Yue, Zengji; Cai, Boyuan; Wang, Lan; Wang, Xiaolin; Gu, Min (2016-03-01). "Intrinsically core-shell plasmonic dielectric nanostructures with ultrahigh refractive index". Science Advances. 2 (3): e1501536. Bibcode:2016SciA....2E1536Y. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1501536. ISSN 2375-2548. PMC 4820380. PMID 27051869.

- ^ Yue, Zengji; Xue, Gaolei; Liu, Juan; Wang, Yongtian; Gu, Min (2017-05-18). "Nanometric holograms based on a topological insulator material". Nature Communications. 8: ncomms15354. Bibcode:2017NatCo...815354Y. doi:10.1038/ncomms15354. PMC 5454374. PMID 28516906.

- ^ Witting, Ian T.; Chasapis, Thomas C.; Ricci, Francesco; Peters, Matthew; Heinz, Nicholas A.; Hautier, Geoffroy; Snyder, G. Jeffrey (June 2019). "The Thermoelectric Properties of Bismuth Telluride". Advanced Electronic Materials. 5 (6). doi:10.1002/aelm.201800904. ISSN 2199-160X.

- ^ Toriyama, Michael; Snyder, G. Jeffrey (2023-11-06), Are Topological Insulators Promising Thermoelectrics?, doi:10.26434/chemrxiv-2023-3nvl3, retrieved 2024-01-07

- ^ Alegria, L. D.; Schroer, M. D.; Chatterjee, A.; Poirier, G. R.; Pretko, M.; Patel, S. K.; Petta, J. R. (2012-08-06). "Structural and Electrical Characterization of Bi

2Se

3 Nanostructures Grown by Metal–Organic Chemical Vapor Deposition". Nano Letters. 12 (9): 4711–4. arXiv:1108.4978. Bibcode:2012NanoL..12.4711A. doi:10.1021/nl302108r. ISSN 1530-6984. PMID 22827514. S2CID 28030427. - ^ Tu, Ngoc Han, Tanabe, Yoichi; Satake, Yosuke, Huynh, Khuong Kim; Le, Phuoc Huu, Matsushita, Stephane Yu; Tanigaki, Katsumi (2017). "Large-Area and Transferred High-Quality Three-Dimensional Topological Insulator Bi2–x Sb x Te3–y Se y Ultrathin Film by Catalyst-Free Physical Vapor Deposition". Nano Letters. 17 (4): 2354–60. arXiv:1601.06541. Bibcode:2017NanoL..17.2354T. doi:10.1021/acs.nanolett.6b05260. PMID 28337910. S2CID 206738534.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wang, Debao; Yu, Dabin; Mo, Maosong; Liu, Xianming; Qian, Yitai (2003-06-01). "Preparation and characterization of wire-like Sb

2Se

3 and flake-like Bi

2Se

3 nanocrystals". Journal of Crystal Growth. 253 (1–4): 445–451. Bibcode:2003JCrGr.253..445W. doi:10.1016/S0022-0248(03)01019-4. ISSN 0022-0248. - ^ Cui, Hongmei; Liu, Hong; Wang, Jiyang; Li, Xia; Han, Feng; Boughton, R.I. (2004-11-15). "Sonochemical synthesis of bismuth selenide nanobelts at room temperature". Journal of Crystal Growth. 271 (3–4): 456–461. Bibcode:2004JCrGr.271..456C. doi:10.1016/j.jcrysgro.2004.08.015. ISSN 0022-0248.

- ^ Jerng, Sahng-Kyoon; Joo, Kisu; Kim, Youngwook; Yoon, Sang-Moon; Lee, Jae Hong; Kim, Miyoung; Kim, Jun Sung; Yoon, Euijoon; Chun, Seung-Hyun (2013). "Ordered growth of topological insulator Bi

2Se

3 thin films on dielectric amorphous SiO2 by MBE". Nanoscale. 5 (21): 10618–22. arXiv:1308.3817. Bibcode:2013Nanos...510618J. doi:10.1039/C3NR03032F. ISSN 2040-3364. PMID 24056725. S2CID 36212915. - ^ a b Geim, A. K.; Grigorieva, I. V. (2013). "Van der Waals heterostructures". Nature. 499 (7459): 419–425. arXiv:1307.6718. doi:10.1038/nature12385. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 23887427. S2CID 205234832.

- ^ a b c Heremans, Joseph P.; Cava, Robert J.; Samarth, Nitin (2017-09-05). "Tetradymites as thermoelectrics and topological insulators". Nature Reviews Materials. 2 (10): 17049. Bibcode:2017NatRM...217049H. doi:10.1038/natrevmats.2017.49. ISSN 2058-8437.

- ^ a b c "Topological Insulators: Fundamentals and Perspectives". Wiley.com. 2015-06-29. Retrieved 2018-07-29.

- ^ a b He, Liang; Kou, Xufeng; Wang, Kang L. (2013-01-31). "Review of 3D topological insulator thin-film growth by molecular beam epitaxy and potential applications". Physica Status Solidi RRL. 7 (1–2): 50–63. Bibcode:2013PSSRR...7...50H. doi:10.1002/pssr.201307003. ISSN 1862-6254. S2CID 97544002.

- ^ Bansal, Namrata; Kim, Yong Seung; Edrey, Eliav; Brahlek, Matthew; Horibe, Yoichi; Iida, Keiko; Tanimura, Makoto; Li, Guo-Hong; Feng, Tian; Lee, Hang-Dong; Gustafsson, Torgny; Andrei, Eva; Oh, Seongshik (2011-10-31). "Epitaxial growth of topological insulator Bi

2Se

3 film on Si(111) with atomically sharp interface". Thin Solid Films. 520 (1): 224–9. arXiv:1104.3438. Bibcode:2011TSF...520..224B. doi:10.1016/j.tsf.2011.07.033. ISSN 0040-6090. S2CID 118512981. - ^ Zhang, Guanhua; Qin, Huajun; Teng, Jing; Guo, Jiandong; Guo, Qinlin; Dai, Xi; Fang, Zhong; Wu, Kehui (2009-08-03). "Quintuple-layer epitaxy of thin films of topological insulator Bi

2Se

3". Applied Physics Letters. 95 (5): 053114. arXiv:0906.5306. Bibcode:2009ApPhL..95e3114Z. doi:10.1063/1.3200237. ISSN 0003-6951. - ^ Richardella, A.; Zhang, D. M.; Lee, J. S.; Koser, A.; Rench, D. W.; Yeats, A. L.; Buckley, B. B.; Awschalom, D. D.; Samarth, N. (2010-12-27). "Coherent heteroepitaxy of Bi

2Se

3 on GaAs (111)B". Applied Physics Letters. 97 (26): 262104. arXiv:1012.1918. Bibcode:2010ApPhL..97z2104R. doi:10.1063/1.3532845. ISSN 0003-6951. - ^ Kong, D.; Dang, W.; Cha, J.J.; Li, H.; Meister, S.; Peng, H. K.; Cui, Y (2010). "SFew-layer nanoplates of Bi

2Se

3 and Bi

2Te

3 with highly tunable chemical potential". Nano Letters. 10 (6): 2245–50. arXiv:1004.1767. Bibcode:2010NanoL..10.2245K. doi:10.1021/nl101260j. PMID 20486680. S2CID 37687875. - ^ Stolyarov, V.S.; Yakovlev, D.S.; Kozlov, S.N.; Skryabina, O.V.; Lvov, D.S. (2020). "Josephson current mediated by ballistic topological states in Bi2Te2.3Se0.7 single nanocrystals". Communications Materials. 1 (1): 38. Bibcode:2020CoMat...1...38S. doi:10.1038/s43246-020-0037-y. S2CID 220295733.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- ^ a b Ginley, Theresa P.; Wang, Yong; Law, Stephanie (2016-11-23). "Topological Insulator Film Growth by Molecular Beam Epitaxy: A Review". Crystals. 6 (11): 154. doi:10.3390/cryst6110154.

- ^ "10 symmetry classes and the periodic table of topological insulators". topocondmat.org. Retrieved 2022-10-11.

- ^ Zhang, X.M.; Liu, E.K.; Liu, Z.Y.; Liu, G.D.; Wu, G.H.; Wang, W.H. (2013-04-01). "Prediction of topological insulating behavior in inverse Heusler compounds from first principles". Computational Materials Science. 70: 145–149. arXiv:1210.5816. doi:10.1016/j.commatsci.2012.12.013. ISSN 0927-0256. S2CID 53506226.

Further reading

[edit]- Hasan, M. Zahid; Kane, Charles L. (2010). "Topological Insulators". Reviews of Modern Physics. 82 (4): 3045–67. arXiv:1002.3895. Bibcode:2010RvMP...82.3045H. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.82.3045. S2CID 16066223.

- Kane, Charles L.; Moore, Joel E. (2011). "Topological Insulators" (PDF). Physics World. 24 (2): 32–36. Bibcode:2011PhyW...24b..32K. doi:10.1088/2058-7058/24/02/36.

- Hasan, M. Zahid; Xu, Su-Yang; Neupane, M (2015). "Topological Insulators, Topological Dirac semimetals, Topological Crystalline Insulators, and Topological Kondo Insulators". In Ortmann, F.; Roche, S.; Valenzuela, S. O. (eds.). Topological Insulators. Wiley. pp. 55–100. doi:10.1002/9783527681594.ch4. ISBN 9783527681594.

- Brumfiel, G. (2010). "Topological insulators: Star material". Nature (Nature News). 466 (7304): 310–1. doi:10.1038/466310a. PMID 20631773.

- Murakami, Shuichi (2010). "Focus on Topological Insulators". New Journal of Physics.

- Moore, Joel E. (July 2011). "Topological Insulators". IEEE Spectrum.

- Ornes, S. (2016). "Topological insulators promise computing advances, insights into matter itself". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 113 (37): 10223–4. doi:10.1073/pnas.1611504113. PMC 5027448. PMID 27625422.

- "The Strange Topology That Is Reshaping Physics". Scientific American. 2017.