2015 BP519

| |

| Discovery[1][2] | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | Dark Energy Survey |

| Discovery site | Cerro Tololo Obs. |

| Discovery date | 17 January 2015 (first observed only) |

| Designations | |

| 2015 BP519 | |

| Caju (nickname)[a] | |

| TNO[3] · ESDO[4] · ETNO distant[2] | |

| Orbital characteristics[3] | |

| Epoch 27 April 2019 (JD 2458600.5) | |

| Uncertainty parameter 5 | |

| Observation arc | 3.22 yr (1,176 d) |

| Aphelion | 820 AU |

| Perihelion | 35.2 AU |

| 428.03 AU | |

| Eccentricity | 0.9178 |

| 8856 yr (3,234,488 d) | |

| 358.39° | |

| 0° 0m 0.36s / day | |

| Inclination | 54.125° |

| 135.11° | |

| ≈ 7 September 2058[5] ±1 month | |

| 348.37° | |

| Physical characteristics | |

| 524 km (est.)[6] 584 km (est.)[4] | |

| 0.08 (assumed)[6] 0.09 (assumed)[4] | |

| 21.5 | |

| 4.4[2][3] | |

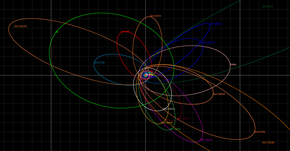

2015 BP519, nicknamed Caju,[a] is an extreme trans-Neptunian object from the scattered disc on a highly eccentric and inclined orbit in the outermost region of the Solar System.[7] It was first observed on 17 January 2015, by astronomers with the Dark Energy Survey at Cerro Tololo Observatory (W84) in Chile.[1][2] It has been described as an extended scattered disc object (ESDO),[4] and fits into the group of extreme objects that led to the prediction of Planet Nine, and has the highest orbital inclination of any of these objects.[a]

Orbit and classification

[edit]2015 BP519 orbits the Sun at a distance of 35.2–821 AU once every 8856 years (3,234,488 days; semi-major axis of 428 AU). Its orbit has an exceptionally high eccentricity of 0.92 and an inclination of 54° with respect to the ecliptic.[3] This makes it a probable outlier among the known extreme trans-Neptunian objects.[3][8]

Planet Nine

[edit]2015 BP519 fits into the group of extreme trans-Neptunian objects that originally led to the prediction of Planet Nine.[a]: 13 The group consists of more than a dozen bodies with a perihelion greater than 30 AU and a semi-major axis greater than 250 AU, with 2015 BP519 having the highest orbital inclination of any of these objects.[a] Subsequently, unrefereed work by de la Fuente Marcos (2018) found that 2015 BP519's current orbital orientation in space is not easily explained by the same mechanism that keeps other extreme trans-Neptunian objects together, suggesting that the clustering in its orbital angles cannot be attributed to Planet Nine's influence.[8] However, regardless of the current direction of its orbit, its high orbital inclination appears to fit into the class of high-semi major axis, high-inclination objects predicted by Batygin & Morbedelli (2017) to be generated by Planet Nine.

Numbering and naming

[edit]The body's observation arc begins with a precovery taken on 27 November 2014 by astronomers with the Dark Energy Survey using the DECam instrument of the Víctor M. Blanco Telescope at Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chile.[2] Its discovery was reported in a paper published by Dark Energy Survey astronomers in 2018.[7]

Physical characteristics

[edit]According to Michael Brown and the Johnston's archive, 2015 BP519 measures 524 and 584 kilometers in diameter based on an assumed albedo of 0.08 and 0.09, respectively.[4] As of 2018, no rotational lightcurve of has been obtained from photometric observations. The body's rotation period, pole and shape remain unknown.[3]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c d e The nickname "Caju" is mentioned in the downloadable PowerPoint presentation "Evaluating the Dynamical Stability of Outer Solar System Objects in the Presence of Planet Nine", by Juliette Becker, Fred Adams, Tali Khain, Stephanie Hamilton, David Gerdes at University of Michigan.

References

[edit]- ^ a b "List Of Centaurs and Scattered-Disk Objects". Minor Planet Center. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- ^ a b c d e "2015 BP519". Minor Planet Center. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f "JPL Small-Body Database Browser: (2015 BP519)" (2018-02-15 last obs.). Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

- ^ a b c d e "List of Known Trans-Neptunian Objects". Johnston's Archive. 7 October 2018. Retrieved 23 October 2018.

- ^ JPL Horizons Observer Location: @sun (Perihelion occurs when deldot changes from negative to positive. Uncertainty in time of perihelion is 3-sigma.)

- ^ a b Brown, Michael E. "How many dwarf planets are there in the outer solar system?". California Institute of Technology. Retrieved 23 October 2018.

- ^ a b Becker, J. C.; Khain, T.; Hamilton, S. J.; Adams, F. C.; Gerdes, D. W.; Zullo, L.; et al. (August 2018). "Discovery and Dynamical Analysis of an Extreme Trans-Neptunian Object with a High Orbital Inclination". The Astronomical Journal. 156 (2): 17. arXiv:1805.05355. Bibcode:2018AJ....156...81B. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/aad042. S2CID 55163842.

- ^ a b de la Fuente Marcos, Carlos; de la Fuente Marcos, Raúl (September 2018). "A Fruit of a Different Kind: 2015 BP519 as an Outlier Among the Extreme Trans-neptunian Objects". Research Notes of the American Astronomical Society. 2 (3): 167. arXiv:1809.02571. Bibcode:2018RNAAS...2c.167D. doi:10.3847/2515-5172/aadfec. S2CID 119433944.

External links

[edit]- Discovery and Dynamical Analysis of an Extreme Trans-Neptunian Object with a High Orbital Inclination, 14 May 2018

- A New World's Extraordinary Orbit Points to Planet Nine 15 May 2018

- 2015 BP519 at AstDyS-2, Asteroids—Dynamic Site

- 2015 BP519 at the JPL Small-Body Database