Battle of Myonessus

| Battle of Myonessus | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Roman–Seleucid War | |||||||

Relief of a Rhodian galley | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Roman Republic Rhodes | Seleucid Empire | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Lucius Aemilius Regillus Eudamus | Polyxenidas | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 80 ships | 89 ships | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

2 ships sunk 1 ship captured |

29 ships sunk 13 ships captured | ||||||

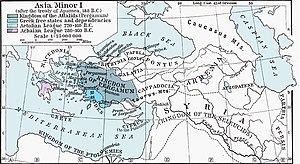

Approximate location of the Battle of Myonessus | |||||||

The Battle of Myonessus took place in September 190 BC. It was fought as part of the Roman–Seleucid War, pitting the fleets of the Roman Republic led by Admiral Lucius Aemilius Regillus and its Rhodian allies under Eudamus against a Seleucid fleet of Polyxenidas.

Polyxenidas attacked his adversaries as they were putting to sea between Myonessus and the Corycus peninsula. The Roman–Rhodian fleet withstood the first assault, managing to assume battle formation. Eudamus then led the Rhodian squadron to the right flank of the Romans, thwarting a Seleucid attempt at encirclement and overpowering the Seleucid seaward wing. Polyxenidas withdrew, having lost half of his fleet. The battle cemented Roman control over the Aegean Sea, enabling them to launch an invasion of Seleucid Asia Minor.

Background

[edit]Following his return from his Bactrian (210–209 BC)[1] and Indian (206–205 BC)[2] campaigns, the Seleucid King Antiochus III the Great forged an alliance with Philip V of Macedon, seeking to jointly conquer the territories of the Ptolemaic Kingdom. In 198 BC, Antiochus emerged victorious in the Fifth Syrian War, taking over Coele-Syria and securing his south-eastern border. He then focused his attention on Asia Minor, launching a successful campaign against coastal Ptolemaic possessions.[3] In 196 BC, Antiochus used the opportunity of Attalus I's death to assault cities controlled by the Attalid dynasty of Pergamon. Fearing that Antiochus would seize the entirety of Asia Minor, the independent cities Smyrna and Lampsacus decided to appeal for protection from the Roman Republic.[4] In the early spring of 196 BC, Antiochus' troops crossed to the European side of the Hellespont and began rebuilding the strategically important city of Lysimachia. In October 196 BC, Antiochus met with a delegation of Roman diplomats in Lysimachia. The Romans demanded that Antiochus withdraw from Europe and restore the autonomous status of Greek city states in Asia Minor. Antiochus countered by claiming that he was simply rebuilding the empire of his ancestor Antiochus II Theos and criticized the Romans for meddling in the affairs of Asia Minor states, whose rights were traditionally defended by Rhodes.[5]

In late winter 196/195 BC, Rome's erstwhile chief enemy, Carthaginian general Hannibal, fled from Carthage to Antiochus' court in Ephesus. Despite the emergence of a pro-war party led by Scipio Africanus, the Roman Senate exercised restraint. The Seleucids expanded their holdings in Thrace from Perinthus to Maroneia at the expense of Thracian tribesmen. Negotiations between the Romans and the Seleucids resumed, coming to a standstill once again, over differences between Greek and Roman law on the status of disputed territorial possessions. In the summer of 193 BC, a representative of the Aetolian League assured Antiochus that the Aetolians would take his side in a future war with Rome, while Antiochus gave tacit support to Hannibal's plans of launching an anti-Roman coup d'état in Carthage.[6] The Aetolians began spurring Greek states to jointly revolt under Antiochus' leadership against the Romans, hoping to provoke a war between the two parties. The Aetolians then captured the strategically important port city of Demetrias, killing the key members of the local pro-Roman faction. In September 192 BC, the Aetolian general Thoantas arrived at Antiochus' court, convincing him to openly oppose the Romans in Greece. The Seleucids selected 10,000 infantry, 500 cavalry, 6 war elephants and 300 ships to be transferred for their campaign in Greece.[7]

Prelude

[edit]The Seleucid fleet sailed via Imbros and Skiathos, arriving at Demetrias where Antiochus' army disembarked.[8] The Achaean League declared war on the Seleucids and Aetolians, with the Romans following suit in November 192 BC. Between December 192 and March 191 BC, Antiochus campaigned in Thessaly and Acarnania.[9] A combined counter offensive conducted by the Romans and their Macedonian allies erased all of Antiochus' gains in Thessaly within a month. On 26 April 191 BC, the two sides faced off at the Battle of Thermopylae, Antiochus' army suffered a devastating defeat and he returned to Ephesus shortly afterwards.[10]

The Romans intended to invade the Seleucid base of operations in Asia Minor which could only be done by crossing the Aegean Sea, the Hellespont being the preferable option due to logistical concerns. Antiochus saw his fleet as disposable, believing that he could still rout the Romans on land. His adversaries on the other hand, could not afford a major defeat at sea, since the manpower to commandeer a new fleet would not be available for months. All while the Roman infantry would struggle to sustain itself, while remaining grounded in mainland Greece.[11] Both sides began hastily reequipping their navies, constructing new warships and drafting seamen.[12] A Roman naval force under Gaius Livius Salinator consisting of 81 ships arrived at Piraeus too late to impact the campaign in mainland Greece. It was therefore dispatched to the Thracian coast, where it was to unite with the navies of the Rhodians and the Attalids. The Seleucids attempted to intercept the Roman fleet before this could be achieved. In September 191 BC, the Roman fleet defeated the Seleucids in the Battle of Corycus, enabling it to take control of several cities including Dardanus and Sestos on the Hellespont.[13]

Following the Battle of Corycus, the Roman–Pergamene fleet at Canae was made up of 77 Roman and 50 Pergamene ships, half of the latter being apertae (merchant galleys capable of fighting[14]). The main Seleucid fleet under Admiral Polyxenidas consisted of 23 large ships, 47 triremes and approximately 100 apertae and was stationed at Ephesus. Hannibal had amassed a second fleet of 37 large ships in Cilicia. Separating the two Seleucid fleets was the Rhodian navy which numbered 75 large ships, mainly quadriremes.[15] In spring 190 BC, the Rhodians dispatched 36 ships under Pausistratos to reinforce the Romans. The Rhodians were blockaded by Polyxenidas at Parormos harbor, Samos. Polyxenidas destroyed the Rhodian fleet through perfidy. A Rhodian exile himself, he convinced Pausistratos that he intended to surrender the Seleucid fleet to the Rhodians. Polyxenidas killed the Rhodian admiral, his erstwhile political opponent, while also capturing 20 ships and sinking 9.[16] The Roman fleet nevertheless managed to rendezvous with 20 Rhodian ships off Samos, where Roman Admiral Lucius Aemilius Regillus took overall command.[17] In August 190 BC, a Rhodian fleet under Admiral Eudamus clashed with Hannibal's fleet at the Battle of the Eurymedon. The more experienced Rhodians managed to outmaneuver Hannibal's ships, destroying half of his fleet.[18] Polyxenidas now found himself outnumbered and isolated, as many independent Asia Minor states had sided with the Romans.[19] In September 190 BC, Aemilius dispatched a part of his fleet to the Hellespont in order to assist the Roman army in its invasion of Asia Minor, Polyxenidas seized the opportunity to attack the Romans at sea.[20]

Battle

[edit]The Roman–Rhodian fleet under Aemilius numbered 58 Roman and 22 Rhodian warships. The Seleucid fleet commanded by Polyxenidas consisted of 89 warships, but while numerically superior its crews were less experienced than those of their adversaries.[21] The allied fleet sailed from its base at Samos to Chios in order to obtain grain, a secondary objective being to relieve the allied city of Notion which had been besieged by Antiochus.[22] While Notion was strategically unimportant, Antiochus anticipated the siege would provoke the Roman navy to intervene.[23] Upon approaching Chios, the Romans took notice of 15 light ships raiding the island. Aemilius rightly assumed that the ships belonged to the Seleucids, chasing them away. The raiders managed to escape to Myonessus, informing Polyxenidas that the allied fleet was likely heading on a punitive expedition to Teos.[22] Teos had abandoned its status as an asylum in order to side with Antiochus.[24] Polyxenidas set up an ambush, hiding his fleet behind the island of Makris and waiting for the Roman–Rhodian fleet to emerge from Teos' narrow northern harbor.[22] The Romans had indeed landed at Teos to force the city to provide them with wine. Unbeknownst to Polyxenidas, a Tean peasant had warned Aemilius that the Seleucid navy was at sea close to the city. Aemilius therefore quickly sailed to the safer southern harbor.[25]

The allied fleet put to sea between Myonessus and the Corycus peninsula, when it was attacked by Polyxenidas.[21] Despite the initial confusion, the Roman–Rhodian fleet managed to assume battle formation. Aemilius held the line until his entire force could exit the straits and then led a counter attack in echelon on the Seleucid right–center. This maneuver exposed the Roman right (seaward) flank to attack and possible encirclement by the numerically superior Seleucids. The Rhodian squadron was positioned on the Roman left (landward) flank and had not yet engaged the enemy due to the long distance between the two sides. Eudamus who commanded the Rhodians, ordered his men to row behind the allied center towards the Roman right wing to reinforce it. While the Seleucids initially outnumbered the Roman right wing by approximately 10 ships, they now found themselves face to face with the entire Rhodian squadron.[26] The Rhodians employed firebaskets, spreading panic on their opponents.[21] The Seleucid landward wing found itself at a considerable distance from the engaging forces,[26] while Aemilius broke through the center and struck the Seleucid seaward wing from the rear.[21]

Polyxenidas realizing that the battle was all but lost, withdrew with his intact landward wing.[21] The Seleucids lost 29 ships sunk and 13 ships captured. While the Roman–Rhodian force suffered two ships sunk and one ship captured. Polyxenidas took what remained of the Seleucid navy, 47 ships in total to Ephesus. The Romans navy cruised outside the city in a show of force before departing to Chios for repairs. The battle solidified Roman control of the Mediterranean Sea for the next six centuries.[26]

Aftermath

[edit]

Aemilius sent a messenger informing consul Lucius Cornelius Scipio Asiaticus that control of the Aegean Sea had been secured. He then sent 30 Roman ships and the Rhodian squadron to the Hellespont to assist with the crossing. The rest of the Rhodian navy blockaded Hannibal at Megiste, while Aemilius led his fleet against Phocaea.[27] Having lost the war at sea, Antiochus withdrew his armies from Thrace, while simultaneously offering to cover half of the Roman war expenses and accept the demands made in Lysimachia in 196 BC. Yet the Romans were determined to crush the Seleucids once and for all.[21]

References

[edit]- ^ Lerner 1999, pp. 45–48.

- ^ Overtoom 2020, p. 147.

- ^ Sartre 2006, pp. 89–90.

- ^ Sartre 2006, pp. 91–92.

- ^ Sarikakis 1974, pp. 57–58.

- ^ Sarikakis 1974, pp. 60–62.

- ^ Sarikakis 1974, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Sarikakis 1974, p. 64.

- ^ Sarikakis 1974, pp. 66–67.

- ^ Sarikakis 1974, pp. 68–69.

- ^ Graigner 2002, pp. 279–281.

- ^ Sarikakis 1974, pp. 72–73.

- ^ Sarikakis 1974, pp. 73–74.

- ^ Graigner 2002, pp. 37.

- ^ Graigner 2002, pp. 281–282.

- ^ Graigner 2002, p. 283.

- ^ Sarikakis 1974, p. 74.

- ^ Sarikakis 1974, pp. 76–77.

- ^ Graigner 2002, p. 284.

- ^ Sarikakis 1974, p. 77.

- ^ a b c d e f Sarikakis 1974, p. 78.

- ^ a b c Graigner 2002, pp. 302–303.

- ^ Waterfield 2014, p. 126.

- ^ Taylor 2013, p. 142.

- ^ Graigner 2002, pp. 303–304.

- ^ a b c Graigner 2002, p. 304.

- ^ Graigner 2002, pp. 304–305.

Sources

[edit]- Graigner, John (2002). The Roman War of Antiochus the Great. Boston: Brill. ISBN 9789004128408.

- Lerner, Jeffrey (1999). The Impact of Seleucid Decline on the Eastern Iranian Plateau: The Foundations of Arsacid Parthia and Graeco-Bactria. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag. ISBN 9783515074179.

- Overtoom, Nikolaus Leo (2020). Reign of Arrows: The Rise of the Parthian Empire in the Hellenistic Middle East. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190888329.

- Sarikakis, Theodoros (1974). "Το Βασίλειο των Σελευκιδών και η Ρώμη" [The Seleucid Kingdom and Rome]. In Christopoulos, Georgios A. & Bastias, Ioannis K. (eds.). Ιστορία του Ελληνικού Έθνους, Τόμος Ε΄: Ελληνιστικοί Χρόνοι [History of the Greek Nation, Volume V: Hellenistic Period] (in Greek). Athens: Ekdotiki Athinon. pp. 55–91. ISBN 978-960-213-101-5.

- Sartre, Maurice (2006). Ελληνιστική Μικρασία: Aπο το Αιγαίο ως τον Καύκασο [Hellenistic Asia Minor: From the Aegean to the Caucaus] (in Greek). Athens: Patakis Editions. ISBN 9789601617565.

- Taylor, Michael (2013). Antiochus The Great. Barnsley: Pen and Sword Military. ISBN 9781848844636.

- Waterfield, Robin (2014). Taken at the Flood: The Roman Conquest of Greece. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199916894.