Battle of Olympus (1941)

| Battle of Olympus | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Balkans Campaign during World War II | |||||||

Nazi Germany's attack on Greece | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Axis: |

Allies: | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Germany: 2nd Panzer Division 5th Mountain Division 100+ tanks [1] |

New Zealand: 5th Infantry Brigade 28th (Māori) Battalion 21st Battalion 22nd Battalion 23rd Battalion Australia: 2/1st Australian Infantry Battalion Unknown number of artillery | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

Germany: Unknown number of men killed or wounded 12 trucks 2 tanks |

New Zealand: 40 men killed 50 wounded 130 captured 9 artillery 10 Bren gun carriers 20 trucks | ||||||

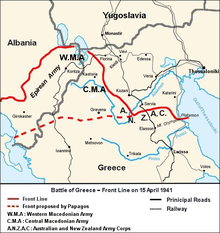

The German invasion of Greece on 6 April 1941 had already been anticipated by the Allied forces. So a defense line was created across the mountain passes near Mount Olympus consisting of British, Australian and New Zealand troops which would prevent the German forces from capturing Thessaly and thereby denying them the opportunity to advance into mainland Greece. However, the speed of the German invasion force had made sure that the endurance of the defending troops and the strength of their defences were very quickly going to be put to the test.[1]

Background

[edit]Greece entered the Second World War on the side of the Allies following an Italian invasion from Albania on 28 October 1940. Greece repulsed the initial Italian attack and a counter-attack in March 1941. Coming to the aid of its struggling ally, Nazi Germany launched an invasion of its own known as Operation Marita, which began on 6 April. While the bulk of the Greek Army was deployed on the Albanian front, German troops invaded from Bulgaria, creating a second front. The Greek army found itself outnumbered in its effort to defend against both Italian and German troops. As a result, the Metaxas defensive line did not receive adequate troop reinforcements and was quickly overrun by the Germans, who then outflanked the Greek forces at the Albanian front, forcing their surrender.[2] Lieutenant-General Henry Maitland Wilson decided to withdraw all Allied forces to the Thermopylae line so they could mound a defence against the invading German Army, and possibly cover their own troops in case an evacuation out of Greece was deemed necessary.[1]

Preparations

[edit]The New Zealand 5th Infantry Brigade under the command of Brigadier James Hargest established blocking positions at the Olympus Pass. The defending forces consisted of the New Zealand 22nd Battalion (Lieutenant Colonel Leslie Andrew), 23rd Battalion (Lieutenant Colonel A. S. Falconer) and 28th (Māori) Battalion (Lieutenant Colonel George Dittmer) who were spread from left to right across the pass where they dug themselves in and constructed defences alongside placing barbed and concertina wire. Meanwhile, the 2/1st Australian Infantry Battalion (lieutenant colonel Ian Ross Campbell) was positioned in Livadero in able to defend the major Allied transport hub at Larissa further south. Finally the New Zealand 21st Battalion (Lieutenant Colonel Neil Lloyd Macky) dug themselves in near a ruined castle on the Platamon Ridge, a high escarpment that blocks the coastal pass to Platamon, so they could await the oncoming German Army. They were ordered to hold their defences until 16 April 1941 with the purpose of delaying the enemy before withdrawing further inland.[3] A final set of patrols were carried out along the Mavroneri riverbed in the night of 13 April after a German party had tried to cross a bridge over the Aliakmon River the evening before, but yielded no enemy contact.[4]

The Battle

[edit]The first encounter of the battle occurred on 14 April 1941 when the German 5th Mountain Division (Major General Julius Ringel) advanced towards the positions held by the New Zealand 22nd Battalion and 28th (Māori) Battalion in the Petra Pass. The German soldiers called out to the New Zealand troops in English in order to confuse the defenders while they defused the mines which were placed by the Allies, but their attempts were unsuccessful. As the 5th Mountain Division continued their assault on the New Zealand positions, they came under artillery and mortar fire which forced them to retreat. At the same time the New Zealand 21st Battalion fended off a series of attacks from the 2nd Panzer Division (Generalleutnant Rudolf Veiel) who were attempting to flank the 2nd New Zealand Division.[5] The Battalion reported the attack which included armoured vehicles, but the ANZAC Corps headquarters initially discounted those claims and told the New Zealand commander that the terrain ahead of his positions were less than ideal for tanks to operate, and that only infantry attacks were expected from there on out.[5]

As the morning of 15 April rolled around, the soldiers of the 28th (Māori) Battalion spotted lines of trucks, troop carriers, tanks and motorcycles, stretching 22.5 kilometers (14 miles) back to Katerini. That night the German motorcycle battalion supported by a tank battalion attacked the ridge where the New Zealand 21st Battalion was stationed. The attack was repelled and inflicted heavy losses on both parties.[6]

The German Army was reinforced during the night of 15 to 16 April and reassembled their tank battalion and motorcycle battalion. Only this time they were joined by an infantry battalion. By 8.30 am the New Zealand artillery had managed to destroy 12 German trucks and 2 tanks. But this didn't halt the 2nd Panzer Division's second assault on the New Zealand held Platamon Ridge. First the German infantry attacked the 21st Battalion's left flank while the tanks advanced along the coast.[7] At the same time the 28th Battalion spotted a number of German troops advancing through the mountains towards their left flank. The 23rd Battalion engaged the nearing enemy and managed to halt their progress at the cost of many men.[1]

When the sun had set and after repelling several infantry attacks, the defenders realised that they were surrounded on nearly all sides. And after having learned of the defeat of the Western Macedonia Army at Korçë against the Italian 9th Army on 15 April.[8] It was decided that the time had come to retreat their posts and fall back to the Thermopylae Line. With the cover of night, the New Zealand 23rd Battalion climbed over part of Mount Olympus in order to head south. They also attempted to take the artillery pieces with them on their retreat, but eventually had to destroy them by throwing them into a ravine so they wouldn't fall into enemy hands. As most of the defending force's transport vehicles had been destroyed by the German attacks,[9] the withdrawal had to be carried out on foot before they could be collected by trucks when they reunited with the main army.[10] The defenders were still attacked by the German forces on their retreat and suffered light casualties before they reached the meet-up point of Pinios Groge across the Pineios river.[11] There the 21st Battalion linked up with the 2/1st Australian Infantry Battalion and covered the retreat of their fellow soldiers from the 2nd New Zealand Division and the Australian 6th Division.[7] The remaining divisions and battalions followed suit while covering their fellow soldiers from the advancing Germans.[12]

Aftermath

[edit]The battle ended up wounding 50 New Zealand soldiers with 40 being killed in action and 130 taken POW alongside the loss of 9 Artillery pieces, 10 Bren gun carriers and 20 trucks. German casualties remain unknown, but they ended up losing 12 trucks and 2 tanks.[13]

British command would eventually decide to abandon Greece and evacuate all Allied troops on 21 April 1941, with all participating troops in the Battle of Olympus making it to the evacuating point on the beaches of the Peloponnese and then Crete.[14] Although Greece was ultimately lost, the defending forces at Mount Olympus were able to halt the German advance for 36 hours which gave the Allies valuable time to regroup their forces and evacuate with as little loss of life as possible.[11]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d "When hell came to the Olympus Pass". neoskosmos.com. 11 May 2018. Retrieved 23 November 2021.

- ^ Dear & Foot 1995, pp. 102–104.

- ^ Cody 1956, p. 51

- ^ Pugsley 2014, p. 78.

- ^ a b Pugsley 2014, p. 85.

- ^ "Story of the 28th". 28maoribattalion.org.nz. Retrieved 23 November 2021.

- ^ a b Blau 1986, p. 98.

- ^ van Crevald 1973, p. 162.

- ^ Pugsley 2014, pp. 87–89.

- ^ Pugsley 2014, p. 91.

- ^ a b Pugsley 2014, pp. 85–87.

- ^ McClymont 1959, pp. 260–262.

- ^ Henderson 1958, pp. 11–31.

- ^ McClymont 1959, pp. 402–403.

Sources

[edit]- Blau, George E. (1986) [1953]. The German Campaigns in the Balkans (Spring 1941) (reissue ed.). Washington, DC: United States Army Center of Military History. OCLC 16940402. CMH Pub 104-4. Archived from the original on 2009-06-19. Retrieved 2022-05-29.

- Cody, J.F (1956). 28 (Maori) Battalion. The Official History of New Zealand in the Second World War 1939–45. Wellington: Historical Publications Branch. OCLC 10848095.

- Dear, I. C. B.; Foot, M. R. D. (1995). The Oxford Companion to the Second World War. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-866225-9.

- Henderson, Jim (1958). 22 Battalion. The Official History of New Zealand in the Second World War 1939–1945. Wellington, New Zealand: Historical Publications Branch.

- McClymont, W. G. (1959). To Greece. Official History of New Zealand in the Second World War 1939–45. Wellington, NZ: War History Branch, Department of Internal Affairs. OCLC 4373298. Retrieved 8 April 2014.

- Pugsley, Christopher (2014). A Bloody Road Home: World War Two and New Zealand's Heroic Second Division. Auckland, New Zealand: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-143-57189-6.

- van Crevald, Alan (1973). Hitler's Strategy 1940–1941: The Balkan Clue. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-052-120-143-8.