Battle of Satala (530)

40°03′00″N 39°36′00″E / 40.050°N 39.600°E

| Battle of Satala | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Iberian War | |||||||

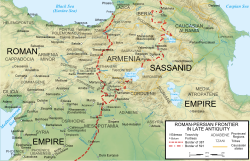

Map of the Byzantine-Persian frontier | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Byzantine Empire | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Mihr-Mihroe |

Sittas Dorotheus | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 30,000[2] | 15,000[3] | ||||||

The Battle of Satala was fought between the forces of the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire and the Sassanid (Persian) Empire in summer 530, near Satala in Byzantine Armenia. The Persian army approached the city to lay siege, when it was attacked in the rear by a small Byzantine force. The Persians turned back to meet them, but were then attacked by the main army from inside the city. A determined attack by a Byzantine unit led to the loss of the Persian general's flag, causing the panicking Persians to retreat.

Background

[edit]In spring 530, the Persian attack in Mesopotamia met with defeat at the Battle of Dara. At the same time, however, the Persians had gained ground in the Caucasus, having subdued Iberia and invaded Lazica. The Persian shah, Kavadh I (r. 488–531), decided to take advantage of this and sent an army into Byzantium's Armenian provinces. For this task, he chose the general Mihr-Mihroe (Mermeroes).[4]

Mihr-Mihroe began assembling his forces near the Byzantine border fortress of Theodosiopolis (Erzurum). According to Procopius, his army composed mostly of levies from Persian-ruled Armenia and Sunitae from the northern Caucasus, as well as 3,000 Sabirs.[5] The Byzantine commanders were Sittas, who had just been promoted from magister militum per Armeniam to magister militum praesentalis, and his successor in the former post, Dorotheus. As soon as news of the ongoing Persian preparations reached them, they sent two of their guards to spy on them. One was captured, but the other returned with information that allowed the Byzantines to launch a surprise attack the Persian camp. The Persian army scattered with some loss, and after looting their camp, the Byzantines returned to their base.[6][7]

Battle

[edit]Once Mihr-Mihroe had finished assembling his army, however, he invaded Byzantine territory. Bypassing Theodosiopolis, he headed for Satala, and set up his camp some distance from the city walls. The Byzantine forces, about half as strong as the Persians according to Procopius, did not engage him. Sittas, with a thousand men, occupied the hills around the city, while the bulk of the Byzantine army remained with Dorotheus inside the walls.[8]

On the next day, the Persians advanced and began to surround the city, preparing for a siege. At this point, Sittas with his detachment sallied forth from the hills. The Persians, seeing them raising much dust and thinking that they were the main Byzantine army, quickly gathered their forces and turned to meet them. Dorotheus then led his own men to attack the Persian rear.[9] Despite their bad tactical position, facing attack from both front and rear, the Persian army resisted effectively, due to its greater numbers. At one point, however, a Byzantine commander, Florentius the Thracian, charged his unit into the Persian centre and managed to capture Mihr-Mihroe's battle standard. Although he was killed soon after, the loss of the flag caused fear among the Persian ranks. Their army began to retreat to their camp, abandoning the battlefield.[10]

Aftermath

[edit]The next day, the Persians departed and returned to Persian Armenia, unmolested by the Byzantines, who were satisfied with their victory over a far larger force.[1] This victory was a major success for Byzantium, and was followed by the defections of a number of Armenian chieftains to the Empire (the brothers Narses, Aratius, and Isaac), as well as by the capture or surrender of a number of important fortresses, like Bolum and Pharangium.[7] Negotiations between Persia and Byzantium also resumed after the battle, but they led nowhere, and in spring 531 war resumed, with the campaign that led to the Battle of Callinicum.[11]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b Procopius. Persian War, I.XV.17.

- ^ Heather, P. J. (Peter J.) (2018). Rome resurgent : war and empire in the age of Justinian. New York, NY. p. 106. ISBN 9780199362745. OCLC 1007044617.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Heather, P. J. (Peter J.) (2018). Rome resurgent : war and empire in the age of Justinian. New York, NY. p. 106. ISBN 9780199362745. OCLC 1007044617.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Greatrex & Lieu 2002, pp. 88–91.

- ^ Procopius. Persian War, I.XV.1–2.

- ^ Procopius. Persian War, I.XV.3–8.

- ^ a b Greatrex & Lieu 2002, p. 91.

- ^ Procopius. Persian War, I.XV.9–11.

- ^ Procopius. Persian War, I.XV.10–13.

- ^ Procopius. Persian War, I.XV.14–16.

- ^ Greatrex & Lieu 2002, pp. 91–92.

Sources

[edit]- Greatrex, Geoffrey; Lieu, Samuel N. C. (2002). The Roman Eastern Frontier and the Persian Wars (Part II, 363–630 AD). New York, New York and London, United Kingdom: Routledge (Taylor & Francis). ISBN 0-415-14687-9.