Cystadenocarcinoma

| Ovarian Cystadenocarcinoma | |

|---|---|

| Other names | cystadenoma carcinoma |

| |

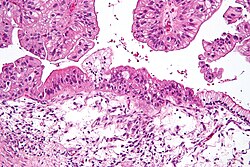

| Intermediate magnification micrograph of a low malignant potential (LMP) mucinous ovarian tumour. H&E stain.

The micrograph shows: Simple mucinous epithelium (right) and mucinous epithelium that pseudo-stratifies (left - diagnostic of a LMP tumour). Epithelium in a frond-like architecture is seen at the top of image. | |

| Specialty | Gynaecological oncology |

| Symptoms | Abdominal pain, Abdominal swelling/distension, Increased abdominal girth, Bloating, ascites, nausea, Vomitting, Unusual Bowel and bladder movement, lack of appetite/early satiety, weightloss, fatigue, vaginal bleeding, acid reflux, shortness of breath |

| Differential diagnosis | ovarian cyst, uterine fibroid, benign uterine lesions, pelvic abscess, pelvic inflammatory disease, adnexal tumours, endometriosis, distended bladder, impacted faecal matter, tumour of appendix, Uterine anomalies, hydro/pyosalpinx, adhesions of bowel or momentum, carcinoma of colon, embryonic adhesions, tracheal cyst, adenocarcinoma of stomach, low-lying caecum, metastasised gastrointestinal carcinoma, ovarian torsion, pelvic kidney, peritoneal cyst, retroperitoneal mass, irritable bowel syndrome. |

| Treatment | surgical debunking surgery with or without chemotherapy |

| Medication | carboplatin, paclitaxel, cisplatin, Liposomal doxorubicin, etoposide, topotecan, gemcitabine, docetaxel, vinorelbine, ifosfamide, fluorouracil, melphalan, altretamine, bevacizumab, olaparib, rucaparib, niraparib, mesna. |

Cystadenocarcinoma is a malignant tumor that arises from glandular epithelial cells and forms cystic structures. It is most commonly found in the ovaries and pancreas, but it can also develop in other organs.[1] The exact cause of cystadenocarcinoma is not well understood, though genetic predisposition, chronic inflammation, and hormonal influences are thought to contribute to its development.[2] The frequency of cystadenocarcinoma varies by type; for example, ovarian cystadenocarcinomas account for a significant proportion of ovarian cancers.[2] This article will cover the different types of cystadenocarcinoma, its pathophysiology, symptoms, diagnosis, treatment, prognosis, and epidemiology.

Epidemiology

[edit]Cystadenocarcinoma incidence varies based on the organ involved.[2] Ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma is the most common subtype of ovarian cancer, with a higher prevalence in postmenopausal women. Risk factors include genetic mutations (e.g., BRCA1/BRCA2), a family history of ovarian or pancreatic cancer, and prolonged exposure to estrogen.[3] Pancreatic mucinous cystadenocarcinoma is rarer, accounting for a small percentage of pancreatic neoplasms, with risk factors including smoking and chronic pancreatitis.[4][5]

Pathophysiology

[edit]Cystadenocarcinomas originate from glandular epithelial cells that undergo malignant transformation. This can lead to the formation of cystic structures filled with retained secretions. Therefore, these tumors are characterized by a proliferation of atypical epithelial cells lining the cystic spaces and often display varying degrees of dysplasia, nuclear atypia, and increased mitotic activity.[2]

The progression from benign cystadenoma to cystadenocarcinoma is driven by genetic and molecular alterations affecting cell proliferation, apoptosis, and invasion. The histological classification of cystadenocarcinomas varies by organ, with ovarian tumors typically exhibiting serous or mucinous differentiation, while pancreatic cystadenocarcinomas often resemble mucinous cystic neoplasms.[2]

Types of Cystadenocarcinoma

[edit]Cystadenocarcinomas can be classified based on their histological features and anatomical location.

Histological Classification

- Serous Cystadenocarcinoma: This type is characterized by the presence of clear, watery fluid within the cysts. The cells typically form a single layer of epithelium with a high degree of nuclear atypia. Serous cystadenocarcinomas are the most common form of cystadenocarcinoma and are often associated with a higher degree of malignancy, especially in ovarian cancers.[2]

- Mucinous Cystadenocarcinoma: These tumors contain thicker, mucous-like secretions within the cysts. The cells are often arranged in a complex architecture with varying degrees of cellular differentiation. Mucinous cystadenocarcinomas are more commonly found in the ovaries and pancreas and have a more variable prognosis depending on their grade.[2][6]

- Papillary Cystadenocarcinoma: This rare subtype is characterized by finger-like projections (papillae) extending into the cystic spaces. Papillary cystadenocarcinomas may be associated with serous or mucinous features and are known for their aggressive nature.[7]

Common Locations

- Ovaries: Ovarian cystadenocarcinomas are the most well-known and studied type, accounting for a significant percentage of ovarian cancers. They are often divided into serous and mucinous subtypes, with serous cystadenocarcinomas being more common. These tumors can be large and may present with symptoms such as abdominal distension, pain, or bloating as they grow.[3]

- Pancreas: These tumors are much less common than ovarian cystadenocarcinomas, representing approximately 1–1.5% of all pancreatic cancers. Pancreatic mucinous cystadenocarcinomas typically occur in middle-aged women and can lead to symptoms such as abdominal pain and jaundice. They are often more difficult to diagnose due to their resemblance to benign cysts on imaging.[4][5]

- Other Locations: Cystadenocarcinomas have also been reported in less common locations such as the breast, liver, colon, rectum, and kidneys. However, these locations are less frequent, and the clinical presentation and prognosis may vary depending on the site of origin.[7]

Signs and Symptoms

[edit]Cystadenocarcinomas can cause many nonspecific symptoms, which vary depending on the tumor's location and progression.[3] Common general symptoms[3] include:

- Abdominal pain, swelling, and distension

- Increased abdominal girth and bloating

- Ascites

- Nausea and vomiting

- Unusual bowel or bladder movements

- Lack of appetite and early satiety

- Weight loss and fatigue

- Vaginal bleeding (in ovarian cystadenocarcinomas)

- Acid reflux or indigestion

- Shortness of breath

These symptoms may worsen as the tumor progresses, with the tumor pressing on nearby organs and leading to more discomfort and potential organ dysfunction. Advanced cases can also cause weight loss, fatigue, and more severe gastrointestinal or respiratory issues.[8]

Diagnosis

[edit]The diagnosis of cystadenocarcinoma involves a combination of imaging, biomarker analysis, and histopathology to confirm malignancy and assess disease progression.[7] Ultrasound is the first-line imaging modality for evaluating ovarian masses, providing an initial assessment of cystic structures. CT and MRI are used to determine tumor size, metastatic spread, and structural involvement, offering a more detailed view of the disease. PET scans help detect distant metastases, aiding in staging and treatment planning.[3]

Biomarker evaluation plays a crucial role in differentiating tumor types. CA-125 is commonly elevated in ovarian serous cystadenocarcinomas and is frequently used to monitor disease progression and response to treatment.[7] In contrast, CEA and CA 19-9 levels may be elevated in pancreatic mucinous cystadenocarcinomas, assisting in diagnosis and prognostic assessment.[4]

Histopathological analysis is essential for definitive diagnosis. Biopsy confirms malignancy and helps differentiate between subtypes based on cellular characteristics. Cytology can also be performed on fluid aspirated from cystic structures, providing further diagnostic insights into the tumor’s nature.[7]

Treatment and Prognosis

[edit]Surgical options are the primary treatment for cystadenocarcinoma, including tumor excision and organ resection (e.g., removal of affected ovaries or other organs).[9] Chemotherapy is commonly used as an adjuvant treatment, with agents such as carboplatin, cisplatin, paclitaxel, etoposide, and gemcitabine showing efficacy in various cases. Other agents like liposomal doxorubicin, docetaxel, and fluorouracil may also be used depending on tumor characteristics and patient response. Emerging therapies include targeted treatments like bevacizumab and PARP inhibitors such as olaparib, rucaparib, and niraparib, which are particularly effective in tumors with specific genetic mutations.[10]

The prognosis for cystadenocarcinoma depends on the tumor's stage, type, and location. Early-stage tumors have a better survival rate, while advanced cases with metastasis have a poorer outlook. Factors affecting prognosis include the tumor’s histological type, response to treatment, and the patient's overall health.[8]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Ovarian papillary cystadenocarcinoma". Female Genital Pathology, WebPath, The Internet Pathology Laboratory for Medical Education. Eccles Health Sciences Library, The University of Utah. Retrieved 2009-03-23.

- ^ a b c d e f g Puls, Larry E.; Powell, Deborah E.; DePriest, Paul D.; Gallion, Holly H.; Hunter, James E.; Kryscio, Richard J.; Van Nagell, J. R. (1992-10-01). "Transition from benign to malignant epithelium in mucinous and serous ovarian cystadenocarcinoma". Gynecologic Oncology. 47 (1): 53–57. doi:10.1016/0090-8258(92)90075-T. ISSN 0090-8258.

- ^ a b c d e "Evaluation and Management of Adnexal Masses". www.acog.org. Retrieved 2025-03-19.

- ^ a b c Wexler A, Waltzman RJ, Macdonald JS (2006-07-11). "Unusual Tumors of the Pancreas". In Raghavan D, Brecher ML, Johnson DH, Meropol NJ, Moots PL, Rose PG (eds.). Textbook of Uncommon Cancer. John Wiley & Sons. p. 368. doi:10.1002/0470030542.ch32. ISBN 978-0-470-03055-4.

- ^ a b King JC, Ng TT, White SC, Cortina G, Reber HA, Hines OJ (October 2009). "Pancreatic serous cystadenocarcinoma: a case report and review of the literature". Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery. 13 (10): 1864–1868. doi:10.1007/s11605-009-0926-3. PMC 2759006. PMID 19459016.

- ^ Hoerl, H. Daniel; Hart, William R. (December 1998). "Primary Ovarian Mucinous Cystadenocarcinomas: A Clinicopathologic Study of 49 Cases With Long-Term Follow-Up". The American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 22 (12): 1449. ISSN 0147-5185.

- ^ a b c d e Dougherty, Cary M.; Aucoin, Ronald; Cotten, Nadalyn (July 1961). "Diagnosis of Cystadenocarcinoma of the Ovary". Obstetrics & Gynecology The Green Journal. 18 (1): 81. ISSN 0029-7844.

- ^ a b Doubeni, Chyke A.; Doubeni, Anna R. B.; Myers, Allison E. (2016-06-01). "Diagnosis and Management of Ovarian Cancer". American Family Physician. 93 (11): 937–944.

- ^ Munnell, Equinn W.; Taylor, Howard C. (1949-11-01). "Ovarian carcinoma: A review of 200 primary and 51 secondary cases". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 58 (5): 943–959. doi:10.1016/0002-9378(49)90201-X. ISSN 0002-9378.

- ^ "Chemotherapy In Advanced Ovarian Cancer: An Overview Of Randomised Clinical Trials". BMJ: British Medical Journal. 303 (6807): 884–893. 1991. ISSN 0959-8138.