Dracula (1958 film)

| Dracula | |

|---|---|

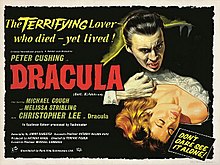

UK theatrical release poster by Bill Wiggins | |

| Directed by | Terence Fisher |

| Screenplay by | Jimmy Sangster |

| Based on | Dracula by Bram Stoker |

| Produced by | Anthony Hinds |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Jack Asher |

| Edited by | Bill Lenny |

| Music by | James Bernard |

| Color process | Technicolor |

Production company | |

| Distributed by |

|

Release dates |

|

Running time | 82 minutes[3] |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Budget | £81,412[4][5] |

| Box office | $3.5 million (worldwide rentals)[6] |

Dracula is a 1958 British gothic horror film directed by Terence Fisher and written by Jimmy Sangster based on Bram Stoker's 1897 novel of the same name. The first in the series of Hammer Horror films starring Christopher Lee as Count Dracula, the film also features Peter Cushing as Doctor Van Helsing, along with Michael Gough, Melissa Stribling, Carol Marsh, and John Van Eyssen. In the United States, the film was retitled Horror of Dracula to avoid confusion with the U.S. original by Universal Pictures, 1931's Dracula.

Production began at Bray Studios on 17 November 1957 with an investment of £81,000.[4] As Count Dracula, Lee fixed the image of the fanged vampire in popular culture.[7] Christopher Frayling writes, "Dracula introduced fangs, red contact lenses, décolletage, ready-prepared wooden stakes and – in the celebrated credits sequence – blood being spattered from off-screen over the Count's coffin."[8] Lee also introduced a dark, brooding sexuality to the character, with Tim Stanley stating, "Lee's sensuality was subversive in that it hinted that women might quite like having their neck chewed on by a stud."[9]

In 2017, a poll of 150 actors, directors, writers, producers and critics for Time Out magazine saw Dracula ranked the 65th best British film ever.[10] Empire magazine ranked Lee's portrayal as Count Dracula the 7th Greatest Horror Movie Character of All Time.[11]

Plot

[edit]

In 1885, Jonathan Harker arrives at Count Dracula's castle near Klausenburg to take up his post as librarian. Inside, he is startled by a young woman who claims to be a prisoner and begs for his help. Dracula arrives, greets Harker, and guides him to his room. Alone, Jonathan writes in his diary, revealing his true intentions: he is a vampire hunter and has come to flush out Dracula.

Sometime later, Harker again is confronted by the woman. She reveals herself to be a vampire and bites his neck. Dracula arrives and pulls her away as Harker passes out. After awakening in his room in daylight, Harker discovers the bite marks on his neck. He realizes he has lost nearly an entire period of daylight. Harker writes a final entry in his journal and hides the book outside the castle. He descends into a crypt to find Dracula and the vampire woman resting in their coffins. Harker first stakes the woman, who withers to old age and dies. He then turns to Dracula's coffin and finds it empty. Dracula, awakened and angry, closes the door to the crypt, trapping Harker.

Days pass, and Doctor Van Helsing arrives in Klausenburg, looking for Harker. An innkeeper's daughter gives him Harker's journal. He travels to Dracula's castle and finds it deserted, but comes across the portrait that Harker had of his fiancée Lucy Holmwood, with the photos now gone. He finds Harker in Dracula's coffin in the crypt, transformed into a vampire. Van Helsing stakes him before leaving for the town of Karlstadt and delivering the news of Harker's death to Arthur Holmwood and his wife Mina, brother and sister-in-law of Lucy, who is ill. When night falls, Lucy opens the doors to her terrace and lays bare her neck—already, it bears the mark of a vampire bite. Dracula then arrives and bites her again.

Mina seeks out Van Helsing's aid in treating Lucy, who begs the maid Gerda to remove his prescribed garlic bouquets and is found dead the next day. Van Helsing turns over Harker's journal to Arthur. Three days after her burial, an undead Lucy lures Gerda's daughter Tania to a graveyard, where Arthur has found Lucy's tomb empty. Van Helsing appears and wards Lucy off with a cross. He explains to Arthur that Lucy was targeted to replace the woman Harker killed. Van Helsing suggests using her to lead them to Dracula, but Arthur refuses, and Van Helsing stakes her in her coffin. Arthur takes one final look at Lucy's body and sees her at peace.

Van Helsing and Arthur travel to the border crossing at Ingolstadt to track down Dracula's coffin. Meanwhile, Mina receives a message supposedly from Arthur, telling her to go to Karlstadt, where Dracula waits. The next day, Arthur and Van Helsing visit the undertaker but find Dracula's coffin missing. Later, Arthur tries to give Mina a cross to wear, which burns her, revealing that she is turning into a vampire herself. During the night, Dracula appears inside the house and bites her. Arthur agrees to give her a blood transfusion administered by Van Helsing. When Arthur asks Gerda to fetch some wine, she tells him Mina forbade her to go down to the cellar. Upon hearing this, Van Helsing bolts downstairs and finds Dracula's coffin, which is empty. Dracula has escaped with Mina, intent on making her his new vampire bride.

A chase ensues as Dracula rushes to return to his castle before sunrise. He attempts to bury Mina alive outside the crypt but is interrupted by Van Helsing and Arthur. Pursuing Dracula inside the castle, Van Helsing struggles with the vampire before eventually tearing down the curtains to let in the sunlight. Van Helsing forms a cross with two candlesticks, driving Dracula into the sun's rays, and he crumbles into dust as Van Helsing looks on. Mina recovers and the cross-shaped scar fades from her hand while Dracula's ashes blow away in the morning breeze, leaving only his clothes and ring behind.

Cast

[edit]- Peter Cushing as Doctor Van Helsing

- Christopher Lee as Count Dracula

- Michael Gough as Arthur Holmwood

- Melissa Stribling as Mina Holmwood

- Carol Marsh as Lucy Holmwood

- John Van Eyssen as Jonathan Harker

- Valerie Gaunt as Vampire Woman

- Olga Dickie as Gerda

- Janina Faye as Tania

- Charles Lloyd-Pack as Doctor Seward

- George Merritt as Policeman

- George Woodbridge as Landlord

- George Benson as Frontier Official

- Miles Malleson as Undertaker

- Geoffrey Bayldon as Porter

- Barbara Archer as Inga

- Paul Cole as Lad

Production

[edit]Concept

[edit]

As Christopher Lee remarked in an interview in Leonard Wolf's A Dream of Dracula: "I was always against the whole tie and tails rendition. Surely it is the height of the ridiculous for a vampire to step out of the shadows wearing white tie, tails, patent leather shoes and a full cloak". Lee said that he never watched any other performances of Dracula until well after making his films, and that when he got the first [Dracula] role with little time to prepare he "had to hurry off to read the book...[and] played it fresh, with no knowledge of previous performances."[12]

In the same interview, Lee said the following about Dracula: "He had also to have an erotic element about him (and not because he sank his teeth into women)... It's a mysterious matter and has something to do with the physical appeal of the person who's draining your life. It's like being a sexual blood donor... Women are attracted to men for any of hundreds of reasons. One of them is a response to the demand to give oneself, and what greater evidence of giving is there than your blood flowing literally from your own bloodstream? It's the complete abandonment of a woman to the power of a man."[13]

Lee believed he had discovered something in the character that hadn't been done before: "And also because I had read the book and I had perhaps discovered something in the character which other people hadn't or hadn't noticed or hadn't decided to present, and that is that the character is heroic, erotic and romantic."[14] He also saw a certain tragedy in Dracula and tried to inject it into playing him: "I've always tried to put an element of sadness, which I've termed the loneliness of evil, into his character. Dracula doesn't want to live, but he's got to! He doesn't want to go on existing as the undead, but he has no choice."[15]

Lee also felt that it was important to stay faithful to Stoker's novel and was frustrated with his Hammer Dracula films: "The stories as I've had them given to me have had almost no relation to the book...which is my reiterated complaint." "My one great regret has always been that I have never been able to present the Count exactly as Bram Stoker described him in every way. This was always due to poor scripts and a lack of imagination on the part of people who never seemed to understand the full potential of the story."[12][16]

Filming

[edit]When Hammer asked for an adaptation of Stoker's novel, screenwriter Jimmy Sangster decided to streamline it to fit it into less than ninety minutes of screen time, and shooting on a low budget within the confines of Bray Studios and its surrounding estate. Working under these limitations, Sangster posited that Jonathan Harker travels to Dracula's castle intending to destroy Dracula (not to complete a real estate transaction, as in the novel) and gets killed, made Arthur Holmwood into Mina's husband and Lucy into Harker's fiancée and Arthur's sister. The characters Renfield and Quincey Morris were dropped completely. The subplot of the harrowing voyage of the ship that carries Dracula and his coffins to England was also abandoned and is replaced in the film by a short hearse ride because all of the action takes place in a relatively small area of Central Europe. The character of Van Helsing also differed from the figure in the original novel. Cushing explained the transformation: "The Curse of Frankenstein became this enormous success, and there I was when I was a younger man, and audiences got used to me looking like that. And I said, 'Now look here, what do we do with Van Helsing? I mean, do you cast a little old man with a beard who speaks Double Dutch or me? It's silly to make me up like that. Why don't you get someone who looks like him?' So we all decided, well, let's forget that and play him as I am, as I was then."[17]

Dracula's ability to transform [into wolf, bat or mist] was dropped for the sake of realism - according to Sangster: "I thought that the idea of being able to change into a bat or a wolf or anything like that made the film seem more like a fairy tale than it needed to be. I tried to ground the script to some extent to reality."[18]

Terence Fisher believed: "My greatest contribution to the Dracula myth was to bring out the underlying sexual element in the story. He [Dracula] is basically sexual. At the moment he bites it is the culmination of a sexual experience."[18] According to Fisher “Dracula preyed upon the sexual frustrations of his woman victims. The (Holmwood) marriage was one in which she [Mina] was not sexually satisfied and that was her weakness as far as Dracula’s approach to her was concerned.”[19] In the scene where Mina returns after a night with Dracula, Fisher's directions to the actress were frank and unambiguous: "When she arrived back after having been away all night she said it all in one close-up at the door. She'd been done the whole night through, please! I remember Melissa [Stribling] saying 'Terry, how should I play the scene?' So I told her, 'Listen, you should imagine you have had one whale of a sexual night, the one of your whole sexual experience. Give me that in your face!'"[18]

According to producer Anthony Hinds when it came to casting Dracula "it never occurred to any of us to use anyone else but Chris Lee". For his role in Horror of Dracula Lee earned £750.[17] Speaking of filming and doing his take on the character, Lee recalled that he "tried to make the character all that he was in the book—heroic, romantic, erotic, fascinating, and dynamic."[17]

Shooting began at Bray Studios on 11 November 1957. Principal photography came to an end on Christmas Eve 1957. Special effects work continued, with the film finally wrapping on 3 January 1958.[18]

Release

[edit]The film received its world premiere in Milwaukee, Wisconsin in the United States on 8 May 1958 as Horror of Dracula.[20][1] It played as a double feature with the Universal-International film The Thing That Couldn't Die.[21] The film opened at the Gaumont Haymarket in London on 21 May 1958.[2]

Critical reception

[edit]

Dracula was well received by critics and fans of Stoker's works. The trade journal reviews from 1958 were very positive. Film Bulletin noted, "As produced by Anthony Hinds in somber mid-Victorian backgrounds... and directed by Terence Fisher with an immense flair for the blood-curdling shot, this Technicolor nightmare should prove a real treat. The James Bernard score is monumentally sinister and the Jack Asher photography full of foreboding atmosphere."[22] Variety called Peter Cushing's performance impressive and wrote that the "serious approach to the macabre theme...adds up to lotsa tension and suspense."[21]

Harrison's Reports was particularly enthusiastic: "Of all the 'Dracula' horror pictures thus far produced, this one, made in Britain and photographed in Technicolor, tops them all. Its shock impact is, in fact, so great that it may well be considered as one of the best horror films ever made. What makes this picture superior is the expert treatment that takes full advantage of the story's shock values."[23]

Vincent Canby in Motion Picture Daily said, "Hammer Films, the same British production unit which last year restored Mary Shelley's Frankenstein to its rightful place in the screen's chamber of horrors, has now even more successfully brought back the granddaddy of all vampires, Count Dracula. It's chillingly realistic in detail (and at times as gory as the law allows). The physical production is first rate, including the settings, costumes, Eastman Color photography and special effects.".[24]

The film holds an approval rating of 89% on Rotten Tomatoes based on 44 reviews, with an average rating of 7.7/10. The website's critical consensus states: "Trading gore for grandeur, Horror of Dracula marks an impressive turn for inveterate Christopher Lee as the titular vampire, and a typical Hammer mood that makes aristocracy quite sexy."[25]

Box office

[edit]The film earned around $3.5 million in theatrical rentals worldwide.[6] It had a record ten-day run in Milwaukee in its premiere engagement.[26] It was one of the twelve most popular films at the British box office in 1958.[27] It earned domestic rentals in North America of $1 million.[28]

Home media

[edit]The film made its first appearance on DVD in 2002 in a U.S. stand-alone disc and was later re-released on 6 November 2007 in a film pack retitled as Horror of Dracula along with Dracula Has Risen from the Grave, Taste the Blood of Dracula, and Dracula A.D. 1972; which was part of Warner Bros. and New Line Cinema's "4 Film Favorites" line of DVDs.[29] On 7 September 2010, Turner Classic Movies released the film in a four-pack along with Dracula Has Risen from the Grave, The Curse of Frankenstein and Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed. The film was released on DVD in the U.K. in October 2002 alongside The Curse of Frankenstein and The Mummy in a box-set entitled Hammer Horror Originals.

The film was digitally restored and re-released in the U.K. by the BFI in 2007. When the film was originally released in the U.K., the BBFC gave it an X rating, being cut, while the 2007 uncut re-release was given a 12A.

For many years, historians pointed to the fact that an even longer, more explicit, version of the film played in Japanese and European cinemas in 1958. Efforts to locate the legendary "Japanese version" of Dracula had been fruitless.

In September 2011, Hammer announced that part of the Japanese release had been found by writer and cartoonist Simon Rowson in the National Film Center at the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo.[30] The first five reels of the film held by the center were destroyed in a fire in 1984, but the last four reels were recovered. The recovered reels include the last 36 minutes of the film and includes two extended scenes, one of which is the discovery of a nearly-complete version of the film's iconic disintegration scene. Some experts rightly note that there is still footage missing from the disintegration scene, as evidenced by stills and the memories of those who had seen the sequence decades before. The announcement mentioned a HD telecine transfer of all four reels with a view for a future U.K. release.[30]

On 29 December 2012, Hammer announced that the restored film would be released on a three-disc, double play Blu-ray Disc set in the U.K. on 18 March 2013. This release contains the 2007 BFI restoration, along with the 2012 high-definition Hammer restoration, which includes footage which was previously believed to be lost.[31] The set contains both Blu-ray Disc and DVD copies of the film, as well as several bonus documentaries covering the film's production, censorship and restoration processes.

The film was further digitally restored by the current domestic rights holder, Warner Bros. Pictures, in association with the BFI, for release in December 2018 on DVD and Blu-ray by the Warner Archive Collection. This version is different from 2002 and 2007 U.S. DVD releases, as the original Universal-International name and logo are restored and the opening credits bear the original Dracula title rather than Horror of Dracula. It also does not contain any of the additional footage that Hammer previously restored.

Sequels

[edit]After the success of Dracula, Hammer went on to produce eight sequels, six of which feature Lee reprising the titular role, and four of which feature Cushing reprising the role of Van Helsing.

- The Brides of Dracula (1960)

- Dracula: Prince of Darkness (1966)

- Dracula Has Risen from the Grave (1968)

- Taste the Blood of Dracula (1970)

- Scars of Dracula (1970)

- Dracula A.D. 1972 (1972)

- The Satanic Rites of Dracula (1973)

- The Legend of the 7 Golden Vampires (1974)

Comic book adaptation

[edit]- The House of Hammer #1 (October 1976), adapted by Dez Skinn and Paul Neary.[32]

See also

[edit]- Dracula (Hammer film series)

- Hammer filmography

- The Curse of Frankenstein (1957), another Hammer film directed by Fisher and starring Cushing and Lee

- Gothic film, a style of cinema rooted in Gothic fiction

- The Mummy (1959 film), another Hammer film directed by Fisher and starring Cushing and Lee

- Vampire films

References

[edit]- ^ a b "When did HORROR OF DRACULA premiere? An Answer. – Where the Long Tail Ends". Where the Long Tail Ends. 25 August 2018. Archived from the original on 26 August 2018. Retrieved 25 August 2018.

- ^ a b Written at London. "Horror Pix Producers to N.Y. 'Dracula' Preem". Variety. New York (published 21 May 1958). 20 May 1958. p. 5. Retrieved 23 January 2021 – via Archive.org.

- ^ "DRACULA (12A)". British Board of Film Classification. 6 August 2013. Archived from the original on 25 March 2017. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

- ^ a b * Rigby, Jonathan (2000). English Gothic: A Century of Horror Cinema. Richmond: Reynolds & Hearn. p. 256. ISBN 9781903111017. OCLC 45576395.

- ^ Vincent L. Barnett (2014) Hammering out a Deal: The Contractual and Commercial Contexts of The Curse of Frankenstein (1957) and Dracula (1958), Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, 34:2, 231–252, DOI: 10.1080/01439685.2013.847650

- ^ a b "Hammer: Five-a-Year for Columbia". Variety. 18 March 1959. p. 19. Retrieved 23 June 2019 – via Archive.org.

- ^ Jackson, Kevin (31 October 2009). "Fangs for the memories: The A-Z of vampires". The Independent. Archived from the original on 4 January 2018. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ^ "Hallowe'en: Why Dracula just won't die". The Telegraph (London). 31 October 2007. Archived from the original on 21 November 2020. Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- ^ "Why Christopher Lee's Dracula didn't suck". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 29 September 2017. Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- ^ Calhoun, Dave; Huddleston, Tom; Jenkins, David; Adams, Derek; Andrew, Geoff; Davies, Adam Lee; Fairclough, Paul; Hammond, Wally (17 February 2017). "The 100 best British movies". Time Out London. Time Out Group. Archived from the original on 3 April 2019. Retrieved 17 October 2024.

- ^ "The 100 best horror movie characters" Archived 3 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Empire. Retrieved 2 December 2017

- ^ a b Michael Bibby, Lauren M. E. Goodlad (2007) "Goth: Undead Subculture", p.298

- ^ Roxana Stuart (1997): "Stage Blood: Vampires of the 19th Century Stage", p.239

- ^ “Listen Back To A 1990 Interview With Actor Christopher Lee” Archived 16 June 2020 at the Wayback Machine. NPR. Retrieved 18 July 2021

- ^ John L. Flynn (1992) Cinematic vampires: the living dead on film and television p.86

- ^ Robert W. Pohle Jr., Douglas C. Hart, Rita Pohle Baldwin (2017): The Christopher Lee Film Encyclopedia, p.120

- ^ a b c Mark A. Miller, David J. Hogan (2020): Christopher Lee and Peter Cushing and Horror Cinema, second edition

- ^ a b c d Berriman, Ian (26 May 2013). "Dracula From the SFX Archives". GamesRadar+. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- ^ Peter Hutchings (2001) Terence Fisher

- ^ "Horror of Dracula (1958) - IMDb". Archived from the original on 7 June 2022. Retrieved 13 August 2022 – via www.imdb.com.

- ^ a b Gilb. (7 May 1958). "Film Reviews: Horror of Dracula". Variety. p. 22. Retrieved 23 January 2021 – via Archive.org.

- ^ "Horror of Dracula". Film Bulletin. Film Bulletin Company. 12 May 1958. p. 12. Retrieved 21 June 2015.

- ^ "'Horror Of Dracula' with Peter Cushing, Christopher Lee and Melissa Stribling". Harrison's Reports. 10 May 1958. p. 74. Retrieved 21 June 2015.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (6 May 1958). "Horror of Dracula". Motion Picture Daily. Quigley Publishing Company. p. 4. Retrieved 21 June 2015.

- ^ "Horror of Dracula (1958)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Archived from the original on 11 November 2020. Retrieved 9 November 2024.

- ^ "National Boxoffice Survey". Variety. New York. 28 May 1958. p. 4. Retrieved 23 January 2021 – via Archive.org.

- ^ "Britain's Money Pacers, 1958". Variety. 15 April 1959. p. 60. Retrieved 23 January 2021 – via Archive.org.

- ^ "Top Grossers of 1958". Variety. 7 January 1959. p. 48. Please note figures are for US and Canada only and are domestic rentals accruing to dsitributors as opposed to theatre gross

- ^ 4 Film Favorites: Draculas (Dracula A.D. 1972, Dracula Has Risen from the Grave, Horror of Dracula, Taste the Blood of Dracula) (DVD). Burbank: Warner Home Video. 2007. ASIN B000U1ZV7G. ISBN 9781419859076. OCLC 801718535.

- ^ a b Hearn, Marcus (14 September 2011). "Dracula Resurrected!". Hammer Films. Archived from the original on 23 November 2011. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ^ "DRACULA on UK Blu-ray". Hammer Films. 29 December 2012. Archived from the original on 30 January 2013. Retrieved 1 February 2013.

- ^ "The House of Hammer #v1#1". Grand Comics Database.

External links

[edit]- Dracula at IMDb

- Dracula at the TCM Movie Database

- Dracula at AllMovie

- Dracula at the BFI's Screenonline

- Dracula at BritMovie (archived)

- 1958 films

- 1958 horror films

- British supernatural horror films

- Dracula films

- Dracula (Hammer film series)

- Films adapted into comics

- Films based on horror novels

- Films directed by Terence Fisher

- Films scored by James Bernard

- Films set in castles

- Films set in Transylvania

- Films set in 1885

- Films shot in Berkshire

- Films shot in England

- Films with screenplays by Jimmy Sangster

- Gothic horror films

- Reboot films

- Hammer Film Productions horror films

- American supernatural horror films

- Universal Pictures films

- Films shot at Bray Studios

- British exploitation films

- 1950s English-language films

- 1950s American films

- 1950s British films

- English-language horror films