Epistles (Plato)

The Epistles (Greek: Ἐπιστολαί; Latin: Epistolae[1]) of Plato are a series of thirteen letters traditionally included in the Platonic corpus. With the exception of the Seventh Letter, they are generally considered to be forgeries; many scholars even reject the seventh. They were "generally accepted as genuine until modern times";[2] but by the close of the nineteenth century, many philologists believed that none of the letters were actually written by Plato.

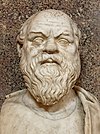

The Epistles focus mostly on Plato's time in Syracuse and his influence on the political figures Dion and Dionysius. They are generally biographical rather than philosophical, although several, notably the Seventh Letter, gesture at the doctrines of Plato's philosophy. Only two, the Second and Seventh, directly reference Plato's teacher Socrates, the major figure within his philosophical dialogues.

Authenticity

[edit]The two letters that are most commonly claimed to have actually been written by Plato are the Seventh and the Eighth, on the supposition that these were open letters and therefore less likely to be the result of invention or forgery. This is not so much because of a presumption in favor of an open letter's authenticity as because of a presumption against that of a private letter: the preservation of the former is unsurprising, while the preservation, dissemination, and eventual publication of the latter requires some sort of explanation.[3]

Nevertheless, even the Seventh Letter has recently been argued to be spurious by prominent scholars, such as Malcolm Schofield,[4] Myles Burnyeat,[5] and Julia Annas.[6] George Boas argues that all of the Epistles, including the Seventh, are spurious,[7] a conclusion accepted also, and more recently, by Terence Irwin.[8]

Structure of the Epistles

[edit]The numbering of each letter is due solely to their placement in traditional manuscripts, and does not appear to follow any discernible principle.[9] The addressees of the Epistles fall into three main categories. Four are addressed to Dionysius II of Syracuse (i, ii, iii, xiii), four to Dionysius' uncle Dion and his associates (iv, vii, viii, x), and five to various others (the Fifth to Perdiccas III of Macedon; the Sixth to Hermias of Atarneus, Erastus, and Coriscus; the Eleventh to Laodamas; and the Ninth and Twelfth to Archytas).

First Letter

[edit]The First Letter is addressed to Dionysius II of Syracuse, and is almost certainly a forgery.[10] In it, Plato supposedly complains of his rude dismissal by Dionysius and predicts an evil end for him. It is interesting mainly for the number of quotations from the tragic poets which it preserves.

The letter purports to have been written to Dionysius the Younger, the tyrant of Syracuse who was introduced to Plato by his uncle Dion in the hopes of turning him to philosophy. It complains of Dionysius' ingratitude for having rudely dismissed Plato after having received such great service from him in the administration of his government and returns the sum which he had provided for travelling expenses as insultingly insufficient. The letter concludes with a number of quotations from tragic poets suggesting that Dionysius will die alone and friendless. R. G. Bury notes that, contrary to the letter's suggestion, Plato never kept watch over Syracuse as a dictator (αυτοκράτωρ),[11] and the account given in this letter of Plato's abrupt dismissal contradicts that given in the Seventh Letter, which has a far greater claim to authenticity. It is consequently valued mostly for preserving the tragic quotations which are hurled at Dionysius.[12]

Second Letter

[edit]The Second Letter is addressed to Dionysius II of Syracuse in response to a supposed complaint he lodged against Plato and his associates that they were slandering him. The letter disclaims any responsibility for these slanders and further denies that they are even occurring. It then counsels Dionysius that a concern for his reputation after his death should incline him to repair his relationship with Plato, since the interactions of political men with the wise is a topic of constant discussion. From this subject, the letter turns to a deliberately enigmatic discussion of "the First," in which Plato warns Dionysius to never write these doctrines down and to burn this letter upon committing its contents to memory. The Second Letter is the source of the oft-cited remark that "no writing of Plato exists or ever will exist, but those now said to be his are those of a Socrates become beautiful and new (καλός καί νέος)."[13]

R. G. Bury argues that the Second Letter is almost certainly inauthentic, based primarily upon conflicts between it and Plato's Seventh Letter and Bury's own conclusion is that its tone and content are decidedly un-Platonic.[14] He considers it to be by the same author as the Sixth Letter.[15]

Third Letter

[edit]The Third Letter is addressed to Dionysius II of Syracuse, complaining of two slanders aimed at Plato, viz. that he had prevented Dionysius II from transforming his tyranny into a monarchy and that Plato was to blame for all the maladministration in Syracuse. The letter responds by recounting Plato's activities in Syracuse, and has the flavor of an open letter.

Bury suggests that the Third Letter, if authentic, was probably written after Plato's third visit to Syracuse in 360 BC, and probably after Dion's seizure of power in 357 BC. He finds the tone to be anachronistic, however, remarks that the parallels to both the Apology of Socrates and the Seventh Letter argue against its authenticity.[16]

Fourth Letter

[edit]The Fourth Letter is addressed to Dion, the uncle and (by this time) ouster of Dionysius II of Syracuse. It encourages Dion in his political efforts, but admonishes him not to forget about the importance of virtue. Bury finds the mixture of flattery and reproof in the letter to be at odds with Plato's friendlier relationship with Dion, even granting that it may be an open letter, and notes conflicts with the Seventh Letter that argue against its authenticity.[17]

Fifth Letter

[edit]The Fifth Letter purports to be a private letter addressed to Perdiccas III, king of Macedon from 365 to 359 BCE. It announces that its author has complied with Perdiccas' request to counsel one Euphraeus to turn his attention to Perdiccas' interests and then proceeds to counsel Perdiccas himself on the advantages of listening to Euphraeus' counsels. Perdiccas is young, and few people are as fit to give advice concerning politics as they claim to be. Echoing the Republic,[18] the letter goes on to say that each form of government (πολιτεία) has its own language or voice (φωνή), and that it is necessary to speak to both gods and men in the voice appropriate to the regime if one is to flourish. Euphraeus will help Perdiccas to explore the speech or logic (λόγος) of monarchy.

The letter next raises a hypothetical objection: Plato himself did not speak to the Athenian democracy, even as the above argument suggests that he knows what would be advantageous to it. It counsels Perdiccas to respond to this objection by saying that Plato was born when his fatherland had already been corrupted beyond the ability of his counsel to benefit it, while the risks of engaging in its politics were great, and that he would probably leave off counseling Perdiccas himself if he thought him incurable.

Bury notes that the discussion of the "voices" of various regimes is borrowed from the Republic[19] and that the explanation of when it is beneficial to give counsel seems borrowed from the Seventh Letter;[20] this suggests that the author had these works before his eyes and was conscientiously trying to sound like Plato when he was writing the Fifth Letter, which would more likely be the case if he were a forger than Plato attempting to be consistent with himself. He also notes that there is no need to defend Plato's abstention from politics given the ostensive purpose of the letter, which is to recommend Euphraeus' competence. Having concluded from this that Plato is not the author, Bury speculates that, "Unless the writer were himself a monarchist, the ascription of this letter to Plato may have been due (as has been suggested) to a malicious desire to paint Plato as a supporter of Macedon and its tyrants."[21]

There is some suggestion that Plato did have some relationship with Perdiccas, though it is difficult to determine the degree to which the Fifth Letter influenced this perception, and thus the relevance of this material in examining its authenticity. A fragment of Carystius' Historical Notes preserved by Athenaeus in Book XI of the Deipnosophistae reports that "Speusippus, learning that Philip was uttering slanders about Plato, wrote in a letter something of this sort: 'As if the whole world did not know that Philip acquired the beginning of his kingship through Plato’s agency. For Plato sent to Perdiccas Euphraeus of Oreus, who persuaded Perdiccas to portion off some territory to Philip. Here Philip kept a force, and when Perdiccas died, since he had this force in readiness, he at once plunged into the control of affairs.'"[22] Demosthenes notes in his Third Philippic that Euphraeus once resided in Athens, and portrays him as being active in politics, albeit in opposition to Philip.[23]

Sixth Letter

[edit]The Sixth Letter is addressed to Hermias, tyrant of Atarneus, and to Erastus and Coriscus, two pupils of Plato residing in Scepsis (a town near Atarneus), advising them to become friends. The letter claims that Plato never met Hermias, contrary to the account given of the latter's life by Strabo; contains a number of parallels to the Second Letter concerning the value of combining wisdom with power, the utility of referring disputes to its author, and the importance of reading and re-reading it; and concludes that all three addresses should publicly swear an oath to strange deities, and to do so half-jestingly. For these reasons, Bury concludes that Sixth Letter is inauthentic and shares its author with the Second Letter.[15]

Seventh Letter

[edit]The Seventh Letter is addressed to the associates and companions of Dion, most likely after his assassination in 353 BC. It is the longest of the Epistles and considered to be the most important. It is most likely an open letter, and contains a defense of Plato's political activities in Syracuse as well as a long digression concerning the nature of philosophy, the theory of the forms, and the problems inherent to teaching. It also espouses the so-called "unwritten doctrine" of Plato which urges that nothing of importance should be committed to writing.

Eighth Letter

[edit]The Eighth Letter is addressed to the associates and companions of Dion, and was probably written some months after the Seventh Letter but before Dion's assassin, Callippus, had been driven out by Hipparinus. It counsels compromise between the parties of Dion and Dionysius the Younger, the former favoring democracy, the latter, tyranny. The compromise would be a monarchy limited by laws.

Ninth Letter

[edit]The Ninth Letter is addressed to Archytas. Cicero attests to its having been written by Plato,[24] but most scholars consider it a literary forgery.

The letter is ostensibly written to Archytas of Tarentum, whom Plato met during his first trip to Sicily in 387 BC. Archytas had sent a letter with Archippus and Philonides, two Pythagoreans who had gone on to mention to Plato that Archytas was unhappy about not being able to get free of his public responsibilities. The Ninth Letter is sympathetic, noting that nothing is more pleasant than to attend to one's own business, especially when that business is the one that Archytas would engage in (viz. philosophy). Yet everyone has responsibilities to one's fatherland (πατρίς), parents, and friends, to say nothing of the need to provide for daily necessities. When the fatherland calls, it is improper not to answer, especially as a refusal will leave politics to the care of worthless men. The letter then declares that enough has been said of this subject, and concludes by noting that Plato will take care of Echecrates, who is still a youth (νεανίσκος), for Archytas' sake and that of Echecrates' father, as well as for the boy himself.

Bury describes the Ninth Letter as "a colourless and commonplace effusion which we would not willingly ascribe to Plato, and which no correspondent of his would be likely to preserve;" he also notes "certain peculiarities of diction which point to a later hand."[25] A character by the name of Echecrates also appears in the Phaedo, though Bury suggests that he, if the same person mentioned here, could hardly have been called a youth by the time Plato met Archytas. Despite the fact that Cicero attests to its having been written by Plato,[26] most scholars consider it a literary forgery.

Tenth Letter

[edit]The Tenth Letter is addressed to an otherwise unknown Aristodorus, who is praised for having remained loyal to Dion, presumably during the latter's exile. Few consider the Tenth Letter to be authentic.[27] It purports to be a private letter of encouragement to an otherwise unknown Aristodorus, commending him for his continued support of Dion, presumably during the latter's exile from Syracuse in his struggle for power with his nephew, Dionysius the Younger. Why such a letter would be preserved is unknown. More damaging to the letter's authenticity is its rather un-Platonic claim that genuine philosophy, which Aristodorus supposedly exhibits to the highest degree, consists entirely of steadfastness, trustworthiness, and sincerity, apparently to the exclusion of any intellectual qualities or even of any particular love of learning: any wisdom or cleverness which tends toward other moral commitments is rightly called "ingenuity" or "daintiness" (Bury translates "parlour-tricks;" Post, "embellishments;" κομψότητας).[28] The treatment of philosophy in simply moral terms, without any reference to intellectual qualities, is foreign enough to Plato's treatment for Bury to declare the letter a forgery.[29] In any event, it consists of a bare three sentences, covering nine lines in the Stephanus pagination.

Eleventh Letter

[edit]The Eleventh Letter is addressed to one Laodamas, who apparently requested assistance in drawing up laws for a new colony. The context of the letter indicates that Laodamas is responsible for helping to institute government in a colony, already understood by the author in the present letter. The author advises that laws alone will be insufficient to govern the colony, or city, without some sort of military or police force which is further tasked with practically enforcing order. It refers to someone named Socrates, though the reference in the letter to the advanced age of Plato means that it cannot be the Socrates who is famous from the dialogues. Bury would allow the authenticity of the letter, were it not for the fact that it claims that this Socrates cannot travel on account of having been enervated by a case of strangury.[30]

Twelfth Letter

[edit]Like the Ninth Letter, the Twelfth Letter is purportedly addressed to Archytas. It thanks him for sending Plato some treatises, which it then goes on to praise effusively, declaring its author worthy of his ancestors and including in their number Myrians, colonists from Troy during the reign of Laomedon. It then promises to send to Archytas some of Plato's unfinished treatises. Diogenes Laërtius preserves this letter in his Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers, as well as a letter from Archytas which presumably occasioned the Twelfth Letter;[31] This letter points to the treatises having been those of Ocellos of Lucania, a Pythagorean. Because the writings which are attributes to Ocellos are forgeries from the First Century BC, the Twelfth Letter is probably also a forgery, and by the same forger, intended to stamp the treatises with Plato's authority.[32] There is no other mention of a Trojan colony in Italy from the reign of Laomedon, let alone of Lucania or the Lucani having been descended from the otherwise unknown "Myrians."[33] R. G. Bury also notes that the Twelfth Letter, along with the Ninth, spell Archytas with an α, whereas Plato spells it in more authoritative epistles with an η (Αρχύτης).[34] Of all the Epistles, it is the only one that is followed by an explicit denial of its authenticity in the manuscripts. In the Stephanus pagination, it spans 359c–e of Vol. III.

Thirteenth Letter

[edit]The Thirteenth Letter is addressed to Dionysius II of Syracuse, and appears to be private in character. The portrait of Plato offered here is in sharp contrast to that the disinterested and somewhat aloof philosopher of the Seventh Letter, leading Bury to doubt its authenticity.[35]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Henri Estienne (ed.), Platonis opera quae extant omnia, Vol. 3, 1578, p. 307.

- ^ Plato's Epistles by Glenn Morrow, 1962, p. 5

- ^ Bury, Introduction to the Epistles, 390–2.

- ^ Malcolm Schofield, "Plato & Practical Politics", in Greek & Roman Political Thought, ed. Schofield & C. Rowe (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 299–302.

- ^ Myles Burnyeat, "The Second Prose Tragedy: a Literary Analysis of the pseudo-Platonic Epistle VII," unpublished manuscript, cited in Malcolm Schofield, Plato (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), 44n19.

- ^ Julia Annas, "Classical Greek Philosophy," in The Oxford History of Greece and the Hellenistic World, ed. Boardman, Griffin and Murray (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991), 285.

- ^ George Boas, "Fact and Legend in the Biography of Plato", 453–457.

- ^ Terence Irwin, "The Intellectual Background," in The Cambridge Companion to Plato, ed. R. Kraut (Cambridge:Cambridge University Press, 1992), 78-79n4.

- ^ Bury, Introduction to the Epistles, 385

- ^ Hamilton and Cairns, Collected Dialogues, 1516

- ^ Plato, Epistle I, 309b

- ^ Bury, Epistle I, 393.

- ^ 314c

- ^ Bury, Epistle II, 398.

- ^ a b Bury, Epistle VI, 454–5.

- ^ Bury, Epistle III, 422–3

- ^ Bury, Epistle IV, 440–1

- ^ Plato, Republic, 493a–c

- ^ Plato, Republic, 493a, b

- ^ Plato, Seventh Letter, 330c ff.

- ^ Bury, Epistle V, 449"

- ^ Athenaeus, Deipnosophistae, 506d–508c.

- ^ Demosthenes, Third Philippic, 59–62.

- ^ Cicero, De Finibus, Bonorum et Malorum, ii. 14; De Officiis, i. 7.

- ^ Bury, Epistle IX, 591.

- ^ Cicero, De Finibus, Bonorum et Malorum, ii. 14; De Officiis, i. 7.

- ^ Bury, Epistle X, 599; Hamilton and Cairns, Collected Dialogues, 1516.

- ^ Bury, Epistle X, 599.

- ^ Bury, Epistle X, 597.

- ^ Bury, Epistle XI, 601.

- ^ Diogenes Laërtius, Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers, Life of Archytus, iv

- ^ Bury, Epistle XII, 607.

- ^ Bury, Epistle XII, 608.

- ^ Bury, Epistle XII, 607; cf. Seventh Letter 338c, 339b, 339d, 350a, Thirteenth Letter 360c.

- ^ Bury, Epistle XIII, 610–3.

References

[edit]- Boas, George. (1949) "Fact and Legend in the Biography of Plato", The Philosophical Review 57 (5): 439–457.

- Bury, R. G. (1929; reprinted 1942) Editor and Translator of Plato's Timaeus, Critias, Cleitophon, Menexenus, Epistles, Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Moore-Blunt, Jennifer (1985) Platonis Epistulae. Teubner.

- Post, L. A. (1925) Thirteen Epistles of Plato. Oxford.

Further reading

[edit]- Harward, John (July–October 1928). "The Seventh and Eighth Platonic Epistles". The Classical Quarterly. 22 (3/4). Cambridge University Press on behalf of The Classical Association: 143–154. doi:10.1017/S0009838800029608. JSTOR 635998.

- Post, L. A. (April 1930). "The Seventh and Eighth Platonic Epistles". The Classical Quarterly. 24 (2). Cambridge University Press on behalf of The Classical Association: 113–115. JSTOR 636598.

- Levison, M.; Morton, A. Q.; Winspear, A. D. (1968). "The Seventh Letter of Plato". Mind. 77 (307). Mind Association: 309–325. doi:10.1093/mind/lxxvii.307.309. JSTOR 2252457.

- Caskey, Elizabeth Gwyn (1974), "Again - Plato's Seventh Letter," Classical Philology 69(3): 220–27.

External links

[edit] Works related to Epistles (Plato) at Wikisource

Works related to Epistles (Plato) at Wikisource- Epistles translated by George Burges

- Free public domain audiobook version of the Epistles

Apocrypha public domain audiobook at LibriVox. Collection includes the Epistles. George Burges, translator (1855).

Apocrypha public domain audiobook at LibriVox. Collection includes the Epistles. George Burges, translator (1855).