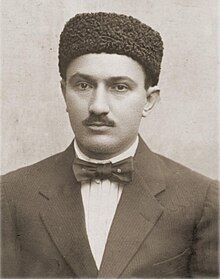

Garegin Apresov

His Excellency Garegin Abramovich Apresov | |

|---|---|

| Гарегин Абрамович Апресов | |

| |

| Soviet Consul General in Urumqi | |

| In office December 1933 – March 1937 | |

| Preceded by | Moisei Nemchenko |

| Succeeded by | Adi Malikov |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 6 January 1890 Qusar, Baku Governorate, Russian Empire |

| Died | 11 September 1941 (aged 51) Medvedev Forest, Oryol, Soviet Union |

| Cause of death | Execution |

| Citizenship | Soviet Union |

| Nationality | Armenian |

| Political party | Communist Party of the Soviet Union |

| Alma mater | Moscow State University |

| Profession | Diplomat |

| Awards | Order of Lenin |

Garegin Abramovich Apresov (Russian: Гарегин Абрамович Апресов; 6 January 1890 – 11 September 1941) was a Soviet diplomat, intelligence officer, and Comintern figure most notable for his tenure in Xinjiang during Sheng Shicai's rule.

Life

[edit]Early years

[edit]Garegin A. Apresov (Apresoff, Apresof) was born to an Armenian family in Qusar in what was then Baku Governorate in Caucasus Viceroyalty of the Russian Empire. His parents lived in Baku, but they had a dacha in Qusar. As a 6th grade student at the gymnasium, in 1908 he joined the revolutionary movement.[1][2][3] He took part in Baku-wide strikes, publishing leaflets and a student magazine. At the end of 1908, the Baku gendarmerie conducted a search of the Apresovs' house, and G. A. Apresov was arrested. He spent several days under arrest.[1]

He studied law at the Moscow University and graduated in 1914. In Moscow he also took part in student protests.[1]

He spoke several foreign languages.[4]

In 1915 he was called up for military service[5] and served as a soldier on the Caucasian Front in the city of Kars. He was later sent to the ensign school in Tiflis. After finishing school, he served on the Persian border in the 4th Cavalry Border Regiment, from where, for anti-war work among the soldiers, he was transferred under supervision to the detachment headquarters and appointed to the position of adjutant of the headquarters.[1]

After the Revolution

[edit]Apresov joined the Communist Party in 1918.[6]

From 1917 to 1918 he was the President of the Lankaran Municipal Council. In March 1918 he was named a member of a government's directorate in Baku and later a member of the Directorate for Food in Baku. He provided assistance in organizing food supplies to Baku, which was experiencing a severe food crisis.[4]

From 1918 - member of the Revolutionary Tribunal in Saratov, where, according to his autobiography, he moved due to illness.[1]

From 1918 to 1919 he was the Leader of the Provincial Justice Department in Saratov.[5]

In 1920, he was involved in underground activity in the Caucasus.[5] Before the Sovietization of Azerbaijan, he worked for the underground Regional Committee, carrying out special tasks for the latter, which mainly boiled down to organizing the financial and monetary operations of the Regional Committee.[1]

From 1921 to 1921, Apresov served as Deputy People's Commissar for Justice of the Azerbaijan SSR and as a commander of a brigade of the Red Army, head of the border troops.[1] Between 1921 and 1922 he was a member of the Collegiate of the People's Commissars for Justice in the Georgian SSR.[5]

Work in Persia

[edit]From 1922 to 1923 he served as the Soviet Consul in Rasht, Persia, from 1924 to 1925 in Isfahan, Persia, and from 1923 to 1926 in Mashhad, Persia. He was also a representative of the Foreign Department of the Joint State Political Directorate (INO OGPU) and Soviet Interim Commissioner for Persia (1923–24).[5][7] According to defector G.S. Agabekov, he was also a representative of Soviet military intelligence and the Comintern.[8] G.S. Agabekov spoke about G.A. Apresov as follows:[8]

Apresov, holding the position of Soviet consul and resident, was simultaneously a representative of the Military Intelligence Directorate and the Comintern and brought the work in Meshed to the proper level. A lawyer by training, very intelligent, well versed in the psychology of the East, fluent in Persian and the Turkic dialect, loving risk and adventure, he was created by nature to work in the OGPU in the East. In addition, he had some practice in his work. While being the Soviet consul in Rasht, he managed to steal the consul's archive through the mistress of the English consul in Rasht, thereby winning the full trust of this institution.

Apresov got to work, and by the middle of 1923, copies of all the secret correspondence of the British consulate in Meshed with the British envoy in Tehran and with the Indian general staff began to arrive from him.

...Despite Apresov’s successes, the OGPU was not satisfied with him, because he sent copies of his reports to the Military Intelligence Directorate and the People’s Commissariat of Foreign Affairs, and the OGPU likes to have a monopoly on information.

He was also described by British diplomats as an ardent communist and energetic propagandist. According to their testimony, the governor of Gilan was completely "under the thumb" of Apresov and supported the communist program.[9] Apresov actively worked with the Armenian diaspora in Persia and tried to influence the church policy of the local Armenian church.[10]

G. A. Apresov was an employee of the Executive Committee of the Comintern.[11]

In 1926 he was summoned to Moscow and removed from his post after an error in his political analysis of the uprising in Khorasan.[10]

In 1927 Apresov was characterized by the plenipotentiary representative of the USSR in Persia, K.K. Yurenev, as an excellent intelligence officer, but also as an employee somewhat inclined to self-promotion and adventurism. Nevertheless, he was recommended by Yurenev for "serious work".[12]

Work in USSR

[edit]Between September 1927 and July 1928, Apresov served as a member of the Military Collegiate of the Supreme Court of the Soviet Union, but resigned at his own request.[13] From 1927 to 1932 he was a People's Commissariat for Foreign Affairs (NKID) agent in Baku. He was NKID's plenipotentiary before the Council of People's Commissars of the Azerbaijan SSR in 1929 and the Uzbek SSR[5] and the Soviet Central Asia in 1930.[7]

Work in China

[edit]

In 1933, Apresov was named the Soviet General Consul with special powers[1] and Representative of the INO OGPU in Urumqi, Xinjiang, China.

The 1930s were marked by a period of close cooperation between the USSR and the Sheng Shicai government in Xinjiang. Soviet agents played a key role in the governance of the region. Three waves of Soviet agents (1931, 1935, and 1936), consisting mainly of Han Chinese living in the USSR, infiltrated the Xinjiang secret police, the People's Anti-Imperialist Association, the Border Affairs Department (which also dealt with intelligence), and other important institutions. This allowed the USSR to exercise significant influence over the governance of the province, and Sheng was often forced to appoint Soviet-trained agents to high positions. All of this activity was coordinated by G.A. Apresov. At a meeting in 1935, Soviet representatives declared their intention to eliminate Sheng if necessary if he no longer met Soviet interests.[14]

In 1935 Apresov became the Commissioner of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks, whose tasks included ensuring that representatives of all departments pursue a single line; employees of other people's commissariats were prohibited from taking any actions that had or could have political significance for the USSR without the prior permission of the Commissioner of the Central Committee.[1][15] Thus, Apresov found himself under dual operational subordination - to the People's Commissariat of Foreign Affairs and the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks). This state of affairs could not please the People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs M.M. Litvinov, who was forced to repeatedly appeal to Stalin with requests to influence his subordinate, who was inclined to lead the local Chinese authorities. "Although Apresov is listed as a plenipotentiary representative," the People's Commissar wrote to I.V. Stalin in December 1936, "he is actually outside my influence, so instructions from me will not achieve their goal."[15] Apresov wielded so much power in Xinjiang that he became generally known as "Tsar" Apresoff.[16] Thus, the British Lieutenant Colonel R. Schomberg noted in this regard: "In a city like Urumqi, the central figure is the Soviet consul. What he does, what he says, what he thinks, where he is going - his every action is of great interest to everyone."[17]

As Consul General, Apresov actively advocated for the accelerated development of Xinjiang's rich natural resources (especially oil). In the summer of 1935, while on vacation in the USSR, he discussed this topic with Stalin.[18]

In 1935 he was awarded the Order of Lenin.[19]

From 1935 to 1936 he was Chief of the Second Eastern Department of the People's Commissariat of Foreign Affairs of the Soviet Union (NKID).[5][7]

There is a known story of Apresov’s involvement in the fate of Yu Xiusong, one of the first members of the Chinese Communist Party, who had a relationship with Sheng Shitong, the younger sister of Sheng Shicai. However, their relationship encountered resistance from Sheng’s family, especially her brother, who doubted the advisability of this union. Apresov played a key role in overcoming these obstacles. Realizing that the marriage could strengthen the relations between the USSR and Sheng Shicai, Apresov personally intervened to convince Sheng Shicai to agree to the wedding. In 1936, a lavish ceremony took place, attended by high-ranking officials, including representatives of the Soviet side. Through Apresov, Stalin gave the newlyweds a box of clothes as a gift.[20] However, in 1937, Yu Xiusong was arrested on charges of belonging to Trotskyists and sent to the USSR, where he was later executed. Sheng Shitong, left alone, devoted her life to finding the truth about her husband’s fate and restoring his good name. After many years of efforts, in 1996, already at an advanced age, she achieved his rehabilitation - The General Prosecutor's Office of the Russian Federation officially restored the reputation of Yu Xiusong, recognizing his complete innocence.[21][20]

There are reviews of Apresov from European travelers. For example, Swedish traveler Sven Hedin, who met Apresov in Urumqi, described him as an open, good-natured and cheerful person.[22] Apresov significantly helped Hedin in obtaining permits from the Chinese authorities to organize his expedition. Hedin was also warmly received at the USSR Consulate General, and a large banquet was organized in honor of the meeting. English traveler and diplomat Eric Teichman was also warmly received at the USSR Consulate General and even participated in the lavish 12-hour celebration of October Revolution Day, which ended with a screening of a Soviet film about Chapayev.[23] After Apresov was arrested by NKVD officers in 1937, he was, among others, accused of espionage with Teichman.[24]

Arrest and death

[edit]In 1937, Chinese warlord Sheng Shicai launched his own purge to coincide with Stalin's Great Purge. He received assistance from the NKVD. Sheng and the Soviets alleged a massive Trotskyist conspiracy and a "Fascist Trotskyite plot" to destroy the Soviet Union. G. A. Apresov was among the 435 alleged conspirators; moreover, he allegedly led the conspiracy.[25][26]

In March 1937[13] he was recalled from service in China and arrested. He was dismissed from the NKID on 13 July 1937.

At first he was held in Butyrka prison in Moscow, and his case was handled by NKVD investigator T. M. Dyakov. Apresov was accused of spying for Britain. Later, Dyakov himself was arrested as an enemy of the people and testified against the Deputy People's Commissar of the NKVD of the USSR L. N. Belsky, who, according to him, gave the order to obtain a confession from G. A. Apresov.[24] Subsequently, both Dyakov and Belsky were shot.

On March 10, 1939, the first session of the Military Collegium of the Supreme Court of the USSR was held, where Apresov's case was heard. During the session, Apresov did not admit his guilt, stating that the confessions he had given earlier were fictitious and had been obtained by the investigator as a result of the use of cruel methods of physical pressure. He pointed out the absurdity of the accusation of connections with British intelligence in light of the fact that he had successfully fought against British influence in Xinjiang. Thus, Apresov stated the following: "in 1933-1934, at my insistence, 60 British agents were arrested in Xinjiang" and "under my leadership, a coup d'etat was carried out in the government in Xinjiang". The court decided to conduct an additional investigation, after which Apresov was transferred to the Sukhanovo special security prison for important political prisoners ("particularly dangerous enemies of the people")[27] nearby Moscow. In this prison, Apresov began to be tortured and tormented and again began to give confessions.[24]

On July 9, 1940, the second session of the Military Collegium of the Supreme Court of the USSR was held to consider the Apresov case. At the session, Apresov again denied his guilt; he stated that he had previously incriminated himself as a result of the use of physical methods of influence, and accused head of NKVD Nikolay Yezhov's former first deputy Mikhail Frinovsky, of slander, with whom he had had a tense relationship since the time they both worked in Baku in 1930. By that time, Frinovsky had already been subjected to repression and was shot. At the court session, G. A. Apresov also stated that as a result of the use of physical methods of influence in Sukhanovo Prison, his teeth were knocked out and he became deaf in one ear. Nevertheless, at this session he was sentenced to 10 years' imprisonment on charges of anti-Soviet activities under Art. 58-10 RSFSR Penal Code. However, charges under Articles 58-8 and 58-11 were dropped against Apresov.[citation needed]

On the same day, July 9, 1940 he wrote a letter to the chairman of the Military Collegium of the Supreme Court of the USSR, in which he stated that "he was forced to incriminate himself under torture" and that "for health reasons he could not endure torture". In the letter, he also said that in his testimony he intentionally introduced fantasy foreign agents with unusual names, which in different languages, including Armenian, mean "Forced Untruth," "All Untruth," "Pure Untruth," "Big Untruth." He called for an assessment of this circumstance and an additional investigation.[24]

In 1941, during the attack of Nazi Germany on the USSR, G. A. Apresov was in prison in the city of Oryol. From the very beginning of the war, the Oryol region was declared under martial law. All cases of crimes against defense, public order and state security were transferred to military tribunals, which received the right to consider cases after 24 hours from the moment the indictment was served. On 8 September 1941, on the basis of Decree No. GKO-634ss, without initiating a criminal case and conducting preliminary and trial proceedings, the Military Collegium of the Supreme Court of the USSR, chaired by Vasiliy Ulrikh (members of the collegium D. Ya. Kandibin and Vasiliy Bukanov), sentenced Apresov and 161 prisoners of the Oryol Prison to death penalty under Art. 58-10 RSFSR Penal Code.[13] He was shot on 11 September 1941 in the Medvedev Forest near Oryol, in an event known as the Medvedev Forest massacre.[5] The execution was initiated by the People's Commissar of Internal Affairs of the USSR L. P. Beria and sanctioned by the State Defense Committee of the USSR headed by I. V. Stalin. All those sentenced were accused of "conducting defeatist agitation and attempts to prepare escapes for the resumption of subversive work."[citation needed]

G. A. Apresov was rehabilitated in 1956.[28][29]

Family

[edit]

Wife - Lidiya Artemyevna Apresova

Brother - Sergei Abramovich Apresov (10.1.1895, Baku - 4.7.1938) - graduate of the Military Medical Academy, head of the hospital in Baku. He was arrested on March 3, 1938, and charged under Art. 21/64, 21/70, 73, 72 of the Criminal Code of the AzSSR by the Military Collegium of the Supreme Court of the USSR. On July 4, 1938, he was sentenced to capital punishment and shot on the same day. S. A. Apresov was rehabilitated by the Military Collegium of the Supreme Court of the USSR on April 14, 1956, for lack of corpus delicti.[30]

Brother - Konstantin Abramovich Apresov

Brother - Tsovak Abramovich Apresov

Brother - Gurgen Abramovich Apresov

Brother - Grigory Abramovich Apresov

In literature

[edit]- Tatiana Ovanessoff's novel "Spy's apprentice: a novel inspired by true events in Persia".[31]

- Alexander Gorokhov's novel "Employee of the Foreign Department of the NKVD".[32]

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i Garegin Apresov Long Autobiography 1937.

- ^ Garegin Apresov Short Autobiography 2.

- ^ Garegin Apresov Short Autobiography 1.

- ^ a b "ASMRB / Sinkiang". asmrb.pbworks.com. Retrieved 2023-11-15.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Апресов, Гарегин Абрамович. Энциклопедия фонда «Хайазг».

- ^ Апресов Георгий (Гарегин) Абрамович

- ^ a b c "АПРЕСОВ Гарегин Абрамович". Archived from the original on 2017-08-15. Retrieved 2017-11-12.

- ^ a b Агабеков, Георгий (2022-04-16). Секретный террор Сталина. Исповедь резидента (in Russian). Litres. ISBN 978-5-457-57347-5.

- ^ "Notes on Garegin Apresov". sso.passport.yandex.ru. Retrieved 2025-02-15.

- ^ a b Minassian, Taline Ter (2019-06-15). Komintern'in Seyyar Militanları: Sovyetler Birliği ve Ortadoğu’daki Azınlıklar (in Turkish). YORDAM KİTAP. ISBN 978-605-172-342-6.

- ^ ИнфоРост, Н. П. "Дело 94. Личное дело АПРЕСОВ Г.А." komintern.dlibrary.org. Retrieved 2025-03-04.

- ^ Yurenev's characteristics of Garegin Apresov, retrieved 2025-02-13

- ^ a b c Zvyagintsev 2005, p. 54.

- ^ Zi Yang "Stalin’s Spies Versus Stalin’s Pawn: The Rise and Recoil of Soviet Influence in Interwar Xinjiang", 2024

- ^ a b "Архив 9 номера 2022 года Советская дипломатическая служба в 1930-х годах: китайское направление". Журнал Международная жизнь. Retrieved 2023-11-15.

- ^ Oriental Affairs: A Monthly Review. 1935.

- ^ "Notes on Garegin Apresov".

- ^ ЕВДОШЕНКО Ю.В. "ВНЕШНЕЭКОНОМИЧЕСКИЕ ПРОЕКТЫ СТАЛИНСКОЙ ПОРЫ: НЕФТЬ СИНЬЦЗЯНА И СОВЕТСКИЙ СОЮЗ (1935-1955 ГГ.)" ЭКОНОМИЧЕСКАЯ ИСТОРИЯ: ЕЖЕГОДНИК, Том: 2020, Год: 2021, Стр.: 264-318.

- ^ "01068". www.knowbysight.info. Retrieved 2023-11-15.

- ^ a b Sotnikova, Irina (2019-12-05). "From the Cohort of the Firsts: Yu Xiusung". Problemy dalnego vostoka (5(2)): 94–106. doi:10.31857/S013128120007508-9. ISSN 0131-2812.

- ^ "苦寻15年,才知丈夫已牺牲,为给丈夫申冤嫁小叔子,83岁得偿所愿_俞秀松_盛世才_新疆". m.sohu.com. Retrieved 2025-03-18.

- ^ Hedin Sven (1936). The Silk Road.

- ^ Teichman, Eric (1937). Journey to Turkistan.

- ^ a b c d The Central Archive of the FSB, archival criminal case No. R-23732 against Apresov Garegin Abramovich.

- ^ Chen, Yong-ling (1990). The Rule of Sinkiang by Feudal Warlord Sheng Shih-ts'ai, a Chameleon in Communist and Nationalist Garb: (1933 - 1944). Stanford Univ., Anthropology Department.

- ^ Whiting and Shih-ts'ai (1958). Sinkiang--Pawn or Pivot.

- ^ "Каталог мемуаров архива общества Мемориал". memoirs.memo.ru. Retrieved 2023-11-15.

- ^ "Списки жертв - дополнения". lists.memo.ru. Retrieved 2023-11-22.

- ^ "Спецобъект 110 СУХАНОВКА: Списки узников". Спецобъект 110 СУХАНОВКА. Retrieved 2023-11-22.

- ^ "Апресов Сергей Абрамович (1895)". Открытый список (in Russian). Retrieved 2023-11-22.

- ^ "The Spy's Apprentice: A Novel Inspired By True Events In Persia". Dorrance Bookstore. Retrieved 2025-02-21.

- ^ Горохов, Александр (2024-07-24). Сотрудник иностранного отдела НКВД (in Russian). Litres. ISBN 978-5-04-662609-4.

Books

[edit]- Zvyagintsev, Vyacheslav Yegorovich (2005). Война на весах Фемиды: война 1941–1945 гг. в материалах следственно-судебных дел (in Russian). Терра.

- 1890 births

- 1941 deaths

- People from Qusar District

- People from Baku Governorate

- Soviet Armenians

- Armenian communists

- Soviet consuls in China

- Moscow State University alumni

- Great Purge victims from Armenia

- People executed by the Soviet Union by firearm

- Members of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union executed by the Soviet Union