Hedjet

| Hedjet | |

|---|---|

Hedjet, the white crown of Upper Egypt | |

| Details | |

| Country | Ancient Upper Egypt |

| Successors | Pschent |

| ||

| Hedjet ḥḏt in hieroglyphs | ||

|---|---|---|

Hedjet (Ancient Egyptian: 𓌉𓏏𓋑, romanized: ḥḏt, lit. 'White One') is the White Crown of pharaonic Upper Egypt. After the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt, it was combined with the Deshret, the Red Crown of Lower Egypt, to form the Pschent, the double crown of Egypt. The symbol sometimes used for the White Crown was the vulture goddess Nekhbet shown next to the head of the cobra goddess Wadjet, the uraeus on the Pschent.[1]

History

[edit]

The white crown, along with the red crown, has a long history with each of their respective representations going back into the Predynastic Period, indicating that kingship had been the base of Egyptian society for some time. The earliest image of the hedjet was thought to have been in the Qustul in Nubia. According to Jane Roy, "At the time of Williams’ argument, the Qustul cemetery and the ‘royal’ iconography found there was dated to the Naqada IIIA period, thus antedating royal cemeteries in Egypt of the Naqada IIIB phase. New evidence from Abydos, however, particularly the excavation of Cemetery U and the tomb U-j, dating to Naqada IIIA has shown that this iconography appears earlier in Egypt".[2]

Frank Yurco stated that depictions of pharaonic iconography such as the royal crowns, Horus falcons and victory scenes were concentrated in the Upper Egyptian Naqada culture and A-Group Nubia. He further elaborated that "Egyptian writing arose in Naqadan Upper Egypt and A-Group Nubia, and not in the Delta cultures, where the direct Western Asian contact was made, which further vitiates the Mesopotamian-influence argument".[3] According to David Wengrow, the A-Group polity of the late 4th millenninum BCE is poorly understood since most of the archaeological remains are submerged underneath Lake Nasser.[4]

Stan Hendrick, John Coleman Darnell and Maria Gatto in 2012 excavated petroglyphic engravings from Nag el-Hamdulab in Aswan, the extreme southern region of Egypt that borders the Sudan, which featured representations of boat procession, solar symbolism and the earliest depiction of the white crown with an estimated dating range between 3200BC and 3100BC.[5]

Nekhbet, the tutelary goddess of Nekhebet (modern el Kab) near Hierakonpolis, was depicted as a woman, sometimes with the head of a vulture, wearing the white crown.[6] The falcon god Horus of Hierakonpolis (Egyptian: Nekhen) was generally shown wearing a white crown.[7] A famous depiction of the white crown is on the Narmer palette found at Hierakonpolis in which the king of the South wearing the hedjet is shown triumphing over his northern enemies. The kings of the united Egypt saw themselves as successors of Horus. Vases from the reign of Khasekhemwy show the king as Horus wearing the white crown.[8]

As with the deshret (red crown), no example of the white crown has been found. It is unknown how it was constructed and what materials were used. Felt or leather have been suggested, but this is purely speculative. Like the deshret, the hedjet may have been woven like a basket from plant fiber such as grass, straw, flax, palm leaf, or reed. The fact that no crown has ever been found, even in relatively intact royal tombs such as that of Tutankhamun, suggests the crowns may have been passed from one monarch to the next, much as in present-day monarchies.

-

Small bronze statuary usage with the hedjet, white crown

-

Bronze statuette of a Kushite king wearing the white crown of Upper Egypt; 25th Dynasty, 670 BCE, Neues Museum, Berlin

-

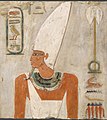

Painted relief of Mentuhotep II from his mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahri; 11th Dynasty, c. 2060–2009 BCE

-

A couple of statuettes which represent a Middle Kingdom pharaoh as King of Upper Egypt (left, with the white crown) and King of Lower Egypt (right, with the red crown); wood, from el-Lisht, 12th dynasty, Middle Kingdom (Egyptian Museum, main floor, room 22, JE44951)

See also

[edit]- Atef – hedjet crown with feathers identified with Osiris

- Khepresh – blue or war crown also called royal crown

References

[edit]- ^ Arthur Maurice Hocart, The Life-Giving Myth, Routledge 2004, p.209

- ^ Roy, Jane (February 2011). The Politics of Trade:Egypt and Lower Nubia in the 4th Millennium BC. Brill. p. 215. ISBN 9789004196117. Retrieved 16 June 2015.

- ^ Frank J.Yurco (1996). "The Origin and Development of Ancient Nile Valley Writing," in Egypt in Africa, Theodore Celenko (ed). Indianapolis, Ind.: Indianapolis Museum of Art. pp. 34–35. ISBN 0-936260-64-5.

- ^ Wengrow, David (2023). "Ancient Egypt and Nubian: Kings of Flood and Kings of Rain" in Great Kingdoms of Africa, John Parker (eds). [S.l.]: THAMES & HUDSON. pp. 1–40. ISBN 978-0500252529.

- ^ Hendrickx, Stan; Darnell, John Coleman; Gatto, Maria Carmela (December 2012). "The earliest representations of royal power in Egypt: the rock drawings of Nag el-Hamdulab (Aswan)". Antiquity. 86 (334): 1068–1083. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00048250. ISSN 0003-598X. S2CID 53631029.

- ^ Cherine Badawi, Egypt, 2004, p.550

- ^ Toby A. H. Wilkinson, Early Dynastic Egypt, Routledge 1999, p.285

- ^ Jill Kamil, The Ancient Egyptians: Life in the Old Kingdom, American Univ in Cairo Press 1996, p.61