History of entheogenic drugs

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2021) |

Entheogenic drugs have been used by various groups for thousands of years. There are numerous historical reports as well as modern, contemporary reports of indigenous groups using entheogens, chemical substances used in a religious, shamanic, or spiritual context.[1][2]

Early history

[edit]One of the oldest known entheogens is peyote, which has been used for at least 5,700 years by Native Americans in Mexico.[3]

20th century

[edit]In 1912 Merck laboratories synthesized the drug 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA), currently known as ecstasy,[4] It was used to enhance psychotherapy beginning in the 1970s and became popular as a street drug in the 1980s.[5][6]

In 1928 Heinrich Klüver was the first to systematically study its psychological effects in a small book called Mescal and Mechanisms of Hallucinations. The book stated that the drug could be used to research the unconscious mind. He coined the term "cobweb figure" in the 1920s to describe one of the four form constant geometric visual hallucinations experienced in the early stage of a mescaline trip: "Colored threads running together in a revolving center, the whole similar to a cobweb". The other three are the chessboard design, tunnel, and spiral. Klüver wrote that "many 'atypical' visions are upon close inspection nothing but variations of these form-constants."[7]

In 1953 Aldous Huxley published The Doors of Perception, in it elaborates on his psychedelic experience under the influence of mescaline in May 1953. Huxley recalls the insights he experienced, ranging from the "purely aesthetic" to "sacramental vision".[8]

MK Ultra

[edit]R. Gordon Wasson had a funded expedition in 1956[9] by the CIA's MK-Ultra subproject 58, as was revealed by documents[10] obtained by John Marks[11] under the Freedom of Information Act. The documents state that Wasson was an 'unwitting' participant in the project.[10]

The funding was provided under the cover name of the Geschickter Fund for Medical Research (credited by Wasson at the end of his subsequent Life piece about the expedition).

On May 13, 1957, Life magazine published an article titled "Seeking the Magic Mushroom", which introduced psychoactive mushrooms to a wide audience for the first time. Just a few days later a personal account by his wife about their research in Mexico was published in the magazine This Week.,[12] it was written by R. Gordon Wasson, ethnomycologist, and Vice President for Public Relations at J.P. Morgan & Co.[13][14][15][16] about the use of psilocybin mushrooms in religious rites of the indigenous Mazatec people of Mexico.

In 1957 Gastón Guzmán Huerta, a Mexican mycologist and anthropologist, was invited by the University of Mexico to assist Rolf Singer, who would arrive to Mexico in 1958 to study the hallucinogenic mushroom genus Psilocybe. While they were in the Huautla de Jiménez region, in their last day of the expeditions, they met R. Gordon Wasson. Guzman became an authority on the genus Psilocybe.

In 1958, the French mycologist Roger Heim brought psilocybin tablets to Mazatec curandera María Sabina, that was the first velada using the active principle of the mushrooms rather than the raw mushrooms themselves took place.[17] In 1962, R. Gordon Wasson and Albert Hofmann went to Mexico to visit her. They also brought a bottle of psilocybin pills.[18] Sandoz was marketing them under the brand name Indocybin—"indo" for both Indian and indole (the nucleus of their chemical structures) and "cybin" for the main molecular constituent, psilocybin. Hofmann gave his synthesized entheogen to the curandera. "Of course, Wasson recalled, Albert Hofmann is so conservative he always gives too little a dose, and it didn't have any effect." Hofmann had a different interpretation: "activation of the pills, which must dissolve in the stomach, takes place after 30 to 45 minutes. In contrast, the mushrooms when chewed, work faster as the drug is absorbed immediately". To settle her doubts about the pills, more were distributed. María, her daughter, and the shaman, Don Aurelio, ingested up to 30 mg each, a moderately high dose by current standards but not perhaps by the more experienced practitioners. At dawn, their Mazatec interpreter reported that María Sabina felt there was little difference between the pills and the mushrooms. She thanked Hofmann for the bottle of pills, saying that she would now be able to serve people even when no mushrooms were available.[19][20]

Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert

[edit]Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert studied and researched the effects of LSD and hallucinogenic mushrooms in the United States and Mexico.

Harvard psilocybin project

[edit]The Harvard Psilocybin Project was a series of experiments in psychology conducted by Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert. The founding board of the project consisted of Leary, Aldous Huxley, David McClelland (Leary's and Alpert's superior at Harvard University),[21] Frank Barron, Ralph Metzner, and two graduate students who were working on a project with mescaline.[22]

In 1960, Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert ordered psilocybin from Swiss-based company Sandoz with the intent to test if different administration modes lead to different experiences. To a greater extent, they believed that psilocybin could be the solution for the emotional problems of the Western man.[23]

Zihuatanejo Project

[edit]The Zihuatanejo Project was a psychedelic training center and intentional community created during the beginning of the counterculture of the 1960s by Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert under the umbrella of their nonprofit group, the International Federation for Internal Freedom (IFIF). The community was located in Zihuatanejo, Guerrero, Mexico, and took up residence at the Hotel Catalina in the summers of 1962 and 1963.[24]

Leary and Alpert first discovered the town of Zihuatanejo in 1960. After the Marsh Chapel Experiment in 1962 they decided the area would make a good location for a training center.[25] The idea for the community was influenced by Aldous Huxley's fictional novel, Island (1962).[26][27]

Thousands of people applied to the IFIF in the hopes of joining the project in Zihuatanejo.[28] Out of this pool of applicants, a small, select group of people were chosen. Amenities cost $200 a month per person, including food and lodging in bungalows near a secluded beach. Fishermen supplied a bounty of fresh fish from the bay. During the first training session in 1962, Leary and 35 guests rented the Catalina Hotel for a month using their own version of the Tibetan Book of the Dead as a guide book for LSD sessions; Ralph Metzner and Richard Alpert helped manage the group.[29] Group LSD sessions began in the morning with the consumption of liquid LSD, with a dosage of 100 to 500 micrograms ingested by participating individuals; the experience would usually last until late afternoon.

Concord Prison Experiment

[edit]The Concord Prison Experiment was designed to evaluate whether the experiences produced by the psychoactive drug psilocybin, derived from psilocybin mushrooms, combined with psychotherapy, could inspire prisoners to leave their antisocial lifestyles behind once they were released. How well it worked was to be judged by comparing the recidivism rate of subjects who received psilocybin with the average for other Concord inmates.

The experiment was conducted between February 1961 and January 1963 in Concord State Prison, a maximum-security prison for young offenders, in Concord, Massachusetts by a team of Harvard University researchers.[30] The team were under the direction of Timothy Leary and included Michael Hollingshead, Allan Cohen, Alfred Alschuder, George Litwin, Ralph Metzner, Gunther Weil, and Ralph Schwitzgebel, with Madison Presnell as the medical and psychiatric adviser. The original study involved the administration of psilocybin manufactured by Sandoz Pharmaceuticals to assist group psychotherapy for 32 prisoners in an effort to reduce recidivism rates. The researchers would administer psilocybin to themselves along with the prisoners, on the grounds of "[creating] a sense of equality and shared experience, and to dispel the fear that often accompanies relationships between [experimenters] and [subjects]".[31]

Alexander Shulgin

[edit]Alexander Shulgin obtained a DEA Schedule I license for an analytical laboratory, which allowed him to synthesize and possess any otherwise ilcit drug, in order to work with scheduled psychoactive chemicals and set up a chemical synthesis laboratory in a small building behind his house, which gave him a great deal of career autonomy. Shulgin used this freedom to synthesize and test the effects of potentially psychoactive drugs such as 2C-B. In 1970s developed new methods of synthesis of MDMA, a drug commonly associated with dance parties, raves, and electronic dance music.[32] It may be mixed with other substances such as ephedrine, amphetamine, and methamphetamine. In 2016, about 21 million people between the ages of 15 and 64 used ecstasy (0.3% of the world population).[33] This was broadly similar to the percentage of people who use cocaine or amphetamines, but lower than for cannabis or opioids.[33] In the United States, as of 2017, about 7% of people have used MDMA at some point in their lives and 0.9% have used it in the last year.[34]

Terence McKenna

[edit]Terence McKenna, along with his brother Dennis, developed a technique for cultivating psilocybin mushrooms using spores they brought to America from the Amazon.[35][36][37][38] In 1976, the brothers published what they had learned in the book Psilocybin: Magic Mushroom Grower's Guide, under the pseudonyms "O.T. Oss" and "O.N. Oeric".[39][40] McKenna and his brother were the first to come up with a reliable method for cultivating psilocybin mushrooms at home.[36][37][39][41] As ethnobiologist Jonathan Ott explains, "[the] authors adapted San Antonio's technique (for producing edible mushrooms by casing mycelial cultures on a rye grain substrate; San Antonio 1971) to the production of Psilocybe [Stropharia] cubensis. The new technique involved the use of ordinary kitchen implements, and for the first time the layperson was able to produce a potent entheogen in his [or her] own home, without access to sophisticated technology, equipment, or chemical supplies."[42] When the 1986 revised edition was published, the Magic Mushroom Grower's Guide had sold over 100,000 copies.[39][40][43]

Heffter Research Institute

[edit]In 1993 by David E. Nichols, Mark Geyer, George Greer, Charles Grob, and Dennis McKenna founded the Heffter Research Institute, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization that promotes research with classic hallucinogens and psychedelics, predominantly psilocybin, to contribute to a greater understanding of the mind and to alleviate suffering. Founded in 1993 as a virtual institute, Heffter primarily funds academic and clinical scientists and made more than $3.1 million in grants between 2011 and 2014.[44][45][46][47] Heffter's recent clinical studies have focused on psilocybin-assisted treatment for end-of-life anxiety and depression in cancer patients, as well as alcohol and nicotine addiction. Several Heffter-supported studies on Spiritual experiences and practices involving ayahuasca and psilocybin have been published.[citation needed]

Influence on artistic movements

[edit]

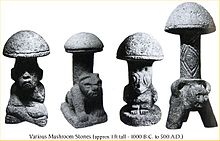

Some of the figures are were-eagle, bat-like features, and were-jaguars, most common, however, is the jaguar transformation figurine which show a wide variety of styles, ranging from human-like figurines to those that are almost completely jaguar, and several where the subject appears to be in a stage of transformation.[48]

Influence on religion

[edit]The Maya displayed characteristic Mesoamerican mythology, with a strong emphasis on an individual being a communicator between the physical world and the spiritual world. Mushroom stone effigies, dated to 1000 BCE, give evidence that mushrooms were at least revered in a religious way.[49]

See also

[edit]- Psilocybin therapy

- List of substances used in rituals

- Ancient use of cannabis

- Psychopharmacology

- List of psychoactive plants, fungi, and animals

- Psilocybin mushrooms

- Psychoactive cacti

- History of LSD

- Entheogenic drugs and the archaeological record

References

[edit]- ^ Souza, Rafael Sampaio Octaviano de; Albuquerque, Ulysses Paulino de; Monteiro, Júlio Marcelino; Amorim, Elba Lúcia Cavalcanti de (October 2008). "Jurema-Preta (Mimosa tenuiflora [Willd.] Poir.): a review of its traditional use, phytochemistry and pharmacology". Brazilian Archives of Biology and Technology. 51 (5): 937–947. doi:10.1590/S1516-89132008000500010.

- ^ Samorini, Giorgio (2019-06-01). "The oldest archeological data evidencing the relationship of Homo sapiens with psychoactive plants: A worldwide overview". Journal of Psychedelic Studies. 3 (2): 63–80. doi:10.1556/2054.2019.008.

- ^ El-Seedi HR, De Smet PA, Beck O, Possnert G, Bruhn JG (October 2005). "Prehistoric peyote use: alkaloid analysis and radiocarbon dating of archaeological specimens of Lophophora from Texas". J Ethnopharmacol. 101 (1–3): 238–42. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2005.04.022. PMID 15990261.

- ^ Freudenmann RW, Öxler F, Bernschneider-Reif S (August 2006). "The origin of MDMA (ecstasy) revisited: the true story reconstructed from the original documents" (PDF). Addiction. 101 (9): 1241–1245. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01511.x. PMID 16911722.

Although MDMA was, in fact, first synthesized at Merck in 1912, it was not tested pharmacologically because it was only an unimportant precursor in a new synthesis for haemostatic substances.

- ^ Anderson L, ed. (18 May 2014). "MDMA". Drugs.com. Drugsite Trust. Archived from the original on 23 March 2016. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- ^ "DrugFacts: MDMA (Ecstasy/Molly)". National Institute on Drug Abuse. February 2016. Archived from the original on 23 March 2016. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- ^ A Dictionary of Hallucations. Oradell, NJ.: Springer. 2010. p. 102.

- ^ Huxley, Aldous (1954) The Doors of Perception, Chatto and Windus, p. 15

- ^ Irvin, Jan (2013). "R. Gordon Wasson: The Man, the Legend, the Myth". In Rush, John (ed.). Entheogens and the Development of Culture. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books. location 10098-10170. ISBN 978-1-58394-624-4.

- ^ a b CIA. "MKUltra Subproject 58 doc 17457 -- JP Morgan & Co. (see Wasson file)" (PDF). National Security Archive, George Washington University. Retrieved 6 May 2016.

- ^ Marks, John (1979). The Search for the Manchurian Candidate. Times Books. p. 114. ISBN 978-0-8129-0773-5.

- ^ Bartlett, Amy (2020-11-11). "The Cost of Omission: Dr. Valentina Wasson and Getting Our Stories Right". Chacruna. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ^ "Medicine: Mushroom Madness". Time. 1958-06-16. Archived from the original on July 15, 2009. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- ^ Tarinas, Joaquim. "ROBERT GORDON WASSON Seeking the Magic Mushroom". Imaginaria.org. Archived from the original on 14 January 2012. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- ^ "R. Gordon Wasson: Archives". Harvard University Herbaria. Archived from the original on 24 August 2009. Retrieved 7 July 2009.

- ^ Jacobs, Travis Beal (2001). Eisenhower at Columbia. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-7658-0036-7.

- ^ Verroust, Vincent (June 2019). "De la découverte des champignons à psilocybine à la renaissance psychédélique". Ethnopharmacologia (61): 12.

- ^ "Ethnopharmacognosy and Human Pharmacology of Salvia divinorum and Salvinorin A". sagewisdom.org. Retrieved 4 July 2021.

- ^ Psychedelics Encyclopedia, pp. 237–238

- ^ "LIFE on LSD". Life. Archived from the original on 26 October 2010.

- ^ "Leary Lectures at Harvard for First Time in 20 Years". The New York Times. 25 April 1983. Retrieved 16 February 2018.

- ^ Stafford, Peter; Jeremy Bigwood (1993). Psychedelics Encyclopedia. Ronin Publishing. ISBN 0-914171-51-8.

- ^ Andrew T. Weil, The Strange Case of the Harvard Drug Scandal, Psychedelic-library.org, 5 November 1963

- ^ Leary, Timothy; Richard Alpert; Ralph Metzner. 1964. "Rationale of the Mexican Psychedelic Training Center". In Richard Blum: Utopiates: The Use and Users of LSD-25, 178-186. New York: Atherton Press. ISBN 0202363244

- ^ Conners, Peter. 2010. White Hand Society: The Psychedelic Partnership of Timothy Leary & Allen Ginsberg. City Lights Books. ISBN 0872865754

- ^ Greenfield, Robert. 2006. Timothy Leary: A Biography. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 0-15603-206-6. 186.

- ^ Lattin, Don. 2011. The Harvard Psychedelic Club: How Timothy Leary, Ram Dass, Huston Smith, and Andrew Weil Killed the Fifties and Ushered in a New Age for America. HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06165-594-5. 2011, 99, 112.

- ^ Lee, Martin A. & Shlain, Bruce. 1992. "Preaching LSD". Acid Dreams: The Complete Social History of LSD: The CIA, the Sixties, and Beyond, Grove Press, ISBN 0-8021-3062-3. 96-98.

- ^ Dass, Ram; Metzner, Ralph; Bravo, Gary. 2010. Birth of a Psychedelic Culture: Conversations about Leary, the Harvard Experiments, Millbrook and the Sixties. Synergetic Press. ISBN 9780907791386

- ^ Leary, Timothy; Metzner, Ralph; Presnell, Madison; Weil, Gunther; Schwitzgebel, Ralph; Kinne, Sarah (July 1965). "A New Behavior Change Program Using Psilocybin". Psychotherapy: Theory, Research & Practice. 2 (2): 61–72. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.1022.1124. doi:10.1037/h0088612.

- ^ Leary, Timothy; Litwin, George; Metzner, Ralph (December 1963). "Reactions to psilocybin administered in a supportive environment". The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 137 (6): 561–573. doi:10.1097/00005053-196312000-00007. PMID 14087676. S2CID 39777572.

- ^ World Health Organization (2004). Neuroscience of Psychoactive Substance Use and Dependence. World Health Organization. pp. 97–. ISBN 978-92-4-156235-5. Archived from the original on 28 April 2016.

- ^ a b World Drug Report 2018 (PDF). United Nations. June 2018. p. 7. ISBN 978-92-1-148304-8. Retrieved 14 July 2018.

- ^ "MDMA (Ecstasy/Molly)". National Institute on Drug Abuse. Retrieved 14 July 2018.

- ^ Lin, Tao (13 August 2014). "Psilocybin, the Mushroom, and Terence McKenna". Vice. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- ^ a b Letcher 2007, pp. 253–274.

- ^ a b Davis, Erik (May 2000). "Terence McKenna's last trip". Wired. Vol. 8, no. 5. Retrieved 2013-09-10.

- ^ McKenna 1993, pp. 205–07.

- ^ a b c Pinchbeck 2003, pp. 232–235.

- ^ a b Letcher 2007, p. 278.

- ^ Martin, Douglas (September 10, 2013). "Terence McKenna, 53, dies; Patron of psychedelic drugs". The New York Times. Retrieved 2012-09-12.

- ^ Ott J. (1993). Pharmacotheon: Entheogenic Drugs, their Plant Sources and History. Kennewick, Washington: Natural Products Company. p. 290. ISBN 978-0-9614234-3-8.; see San Antonio JP. (1971). "A laboratory method to obtain fruit from cased grain spawn of the cultivated mushroom, Agaricus bisporus". Mycologia. 63 (1): 16–21. doi:10.2307/3757680. JSTOR 3757680. PMID 5102274.

- ^ McKenna & McKenna 1976, Preface (revised ed.).

- ^ "Guidestar". Guidestar USA. 1 May 2016.

- ^ "Guidestar" (PDF). Guidestar. January 2015. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- ^ "Guidestar" (PDF). January 2013. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- ^ "Guidestar" (PDF). January 2012. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- ^ Diehl 2004, p. 106.

- ^ Tedlock 1992, pp. 46–53.

Works cited

[edit]- Diehl, Richard (2004). The Olmecs: America's First Civilization. Ancient peoples and places series. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-02119-8. OCLC 56746987.

- Letcher, Andy (2007). "14.The Elf-Clowns of Hyperspace". Shroom: A Cultural History of the Magic Mushroom. Harper Perennial. ISBN 978-0060828295.

- McKenna, Terence; McKenna, Dennis (1976). Psilocybin: Magic Mushroom Grower's Guide. Under the pseudonyms OT Oss and ON Oeric. Berkeley, CA: And/Or Press. ISBN 978-0-915904-13-6.

- McKenna, Terence (1993). True Hallucinations: Being an Account of the Author's Extraordinary Adventures in the Devil's Paradise. San Francisco: Harper San Francisco. ISBN 978-0-06-250545-3.

- Pinchbeck, Daniel (2003). Breaking Open the Head: A Psychedelic Journey into the Heart of Contemporary Shamanism. Broadway Books. ISBN 978-0-7679-0743-9.

- Tedlock, Barbara (1992). Time and the Highland Maya. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 9780826313423.

External links

[edit]- Psychedelic Timeline by Tom Frame. Psychedelic Times.