History of psychiatry

History of Psychiatry

[edit]

History of psychiatry is the study of the history of and changes in psychiatry, a medical specialty which diagnoses, prevents and treats mental disorders

Ancient

[edit]Specialty in psychiatry can be traced in Ancient India.[1] The oldest texts on psychiatry include the ayurvedic text, Charaka Samhita.[2][3] Some of the first hospitals for curing mental illness were established during the 3rd century BCE.[4]

During the 5th century BCE, mental disorders, especially those with psychotic traits, were considered supernatural in origin,[5] a view which existed throughout ancient Greece and Rome.[5] The beginning of psychiatry as a medical specialty is dated to the middle of the nineteenth century,[6] although one may trace its germination to the late eighteenth century.

Some of the early manuals about mental disorders were created by the Greeks.[6] In the 4th century BCE, Hippocrates theorized that physiological abnormalities may be the root of mental disorders.[5] In 4th- to 5th-century BCE Greece, Hippocrates wrote that he visited Democritus and found him in his garden cutting open animals. Democritus explained that he was attempting to discover the cause of madness and melancholy. Hippocrates praised his work. Democritus had with him a book on madness and melancholy.[7]

Religious leaders often turned to versions of exorcism to treat mental disorders, often utilizing methods that many consider to be cruel and/or barbaric.[5]

Middle Ages

[edit]A number of hospitals known as bimaristans were built throughout Arab countries beginning around the early 9th century, with the first in Baghdad.[8] They sometimes contained wards for mentally ill patients, typically those who exhibited violence or had debilitating chronic illness.[9]

Physicians who wrote on mental disorders and their treatment in the Medieval Islamic period included Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi (Rhazes), the Arab physician Najab ud-din Muhammad[citation needed], and Abu Ali al-Hussain ibn Abdallah ibn Sina, known in the West as Avicenna.[10][11][12]

Specialist hospitals were built in medieval Europe from the 13th century to treat mental disorders but were utilized only as custodial institutions and did not provide any type of treatment.[13]

Early modern period

[edit]

During the early modern period, mentally ill people were often held captive in cages or kept up within the city walls, or they were compelled to amuse members of courtly society.[14]

From the 13th century onwards, sick and poor people were kept in newly founded ecclesiastical hospitals, such as the "Spittal sente Jorgen" erected in 1212 in Leipzig, in Saxony, Germany. Here, those with serious mental problems were isolated from the rest of the community in accordance with contemporary European practice.[14] Also founded in the 13th century, Bethlem Royal Hospital in London was one of the oldest lunatic asylums.[13]

In the late 17th century, privately run asylums for the insane began to proliferate and expand in size. Already in 1632 it was recorded that Bethlem Royal Hospital, London had "below stairs a parlor, a kitchen, two larders, a long entry throughout the house, and 21 rooms wherein the poor distracted people lie, and above the stairs eight rooms more for servants and the poor to lie in".[15] Inmates who were deemed dangerous or disturbing were chained, but Bethlem was an otherwise open building for its inhabitants to roam around its confines and possibly throughout the general neighborhood in which the hospital was situated.[16] In 1676, Bethlem expanded into newly built premises at Moorfields with a capacity for 100 inmates.[17]: 155 [18]: 27

In 1621, Oxford University mathematician, astrologer, and scholar Robert Burton published one of the earliest treatises on mental illness, The Anatomy of Melancholy, What it is: With all the Kinds, Causes, Symptomes, Prognostickes, and Several Cures of it. In Three Maine Partitions with their several Sections, Members, and Subsections. Philosophically, Medicinally, Historically, Opened and Cut Up. Burton thought that there was "no greater cause of melancholy than idleness, no better cure than business." Unlike English philosopher of science Francis Bacon, Burton argued that knowledge of the mind, not natural science, is humankind's greatest need.[19]

In 1656, Louis XIV of France created a public system of hospitals for those with mental disorders, but as in England, no real treatment was applied.[20]

In 1713, the Bethel Hospital Norwich was opened, the first purpose-built asylum in England, founded by Mary Chapman.[21]

Humanitarian reform

[edit]In Saxony, a new social policy was implemented at the beginning of the 18th century in which criminals, prostitutes, vagrants, orphans, and the mentally ill were incarcerated and re-educated in the concepts of the Enlightenment. As a result, a variety of jails, approved schools, and insane asylums were constructed, including the hospital "Chur-Sachisches Zucht-Waysen und Armen-Haus" in Waldheim in 1716, which was the first governmental institution dedicated to the care of the mentally ill on the German territory.[14]

Attitudes towards the mentally ill began to change. It came to be viewed as a disorder that required compassionate treatment that would aid in the rehabilitation of the victim. In 1758, English physician William Battie wrote his Treatise on Madness on the management of mental disorder. It was a critique aimed particularly at the Bethlem Hospital, where a conservative regime continued to use barbaric custodial treatment. Battie argued for a tailored management of patients entailing cleanliness, good food, fresh air, and distraction from friends and family. He argued that mental disorder originated from dysfunction of the material brain and body rather than the internal workings of the mind.[22][23]

Thirty years later, then ruling monarch in England George III was known to have a mental disorder.[5] Following the King's remission in 1789, mental illness came to be seen as something which could be treated and cured.[5] The introduction of moral treatment was initiated independently by the French doctor Philippe Pinel and the English Quaker William Tuke.[5]

In 1792, Pinel became the chief physician at the Bicêtre Hospital. In 1797, Jean-Baptiste Pussin first freed patients of their chains and banned physical punishment, although straitjackets could be used instead.[24][25]

Patients were allowed to move freely about the hospital grounds, and eventually dark dungeons were replaced with sunny, well-ventilated rooms. Pussin and Pinel's approach was seen as remarkably successful and they later brought similar reforms to a mental hospital in Paris for female patients, La Salpetrière. Pinel's student and successor, Jean Esquirol (1772–1840), went on to help establish 10 new mental hospitals that operated on the same principles. There was an emphasis on the selection and supervision of attendants in order to establish a suitable setting to facilitate psychological work, and particularly on the employment of ex-patients as they were thought most likely to refrain from inhumane treatment while being able to stand up to pleading, menaces, or complaining.[26]

William Tuke led the development of a radical new type of institution in northern England, following the death of a fellow Quaker in a local asylum in 1790.[27]: 84–85 [28]: 30 [29] In 1796, with the help of fellow Quakers and others, he founded the York Retreat, where eventually about 30 patients lived as part of a small community in a quiet country house and engaged in a combination of rest, talk, and manual work. Rejecting medical theories and techniques, the efforts of the York Retreat centered around minimizing restraints and cultivating rationality and moral strength. The entire Tuke family became known as founders of moral treatment.[30]

William Tuke's grandson, Samuel Tuke, published an influential work in the early 19th century on the methods of the retreat; Pinel's Treatise On Insanity had by then been published, and Samuel Tuke translated his term as "moral treatment". Tuke's Retreat became a model throughout the world for humane and moral treatment of patients with mental disorders.[30] The York Retreat inspired similar institutions in the United States, most notably the Brattleboro Retreat and the Hartford Retreat (now The Institute of Living).

Although Tuke, Pinel and others had tried to do away with physical restraint, it remained widespread into the 19th century. At the Lincoln Asylum in England, Robert Gardiner Hill, with the support of Edward Parker Charlesworth, pioneered a mode of treatment that suited "all types" of patients, so that mechanical restraints and coercion could be dispensed with — a situation he finally achieved in 1838. In 1839, Sergeant John Adams and Dr. John Conolly were impressed by the work of Hill, and introduced the method into their Hanwell Asylum, by then the largest in the country. Hill's system was adapted, since Conolly was unable to supervise each attendant as closely as Hill had done. By September 1839, mechanical restraint was no longer required for any patient.[31][32]

Phrenology

[edit]

Scotland's Edinburgh medical school of the eighteenth century developed an interest in mental illness, with influential teachers including William Cullen (1710–1790) and Robert Whytt (1714–1766) emphasising the clinical importance of psychiatric disorders. In 1816, the phrenologist Johann Spurzheim (1776–1832) visited Edinburgh and lectured on his craniological and phrenological concepts; the central concepts of the system were that the brain is the organ of the mind and that human behaviour can be usefully understood in neurological rather than philosophical or religious terms. Phrenologists also laid stress on the modularity of mind.

Some of the medical students, including William A. F. Browne (1805–1885), responded very positively to this materialist conception of the nervous system and, by implication, of mental disorder. George Combe (1788–1858), an Edinburgh solicitor, became an unrivaled exponent of phrenological thinking, and his brother, Andrew Combe (1797–1847), who was later appointed a physician to Queen Victoria, wrote a phrenological treatise entitled Observations on Mental Derangement (1831). They also founded the Edinburgh Phrenological Society in 1820.

Institutionalization

[edit]The modern era of providing care for the mentally ill began in the early 19th century with a large state-led effort. Public mental asylums were established in Britain after the passing of the 1808 County Asylums Act. This empowered magistrates to build rate-supported asylums in every county to house the many 'pauper lunatics'. Nine counties first applied, and the first public asylum opened in 1812 in Nottinghamshire. Parliamentary Committees were established to investigate abuses at private madhouses like Bethlem Hospital - its officers were eventually dismissed and national attention was focused on the routine use of bars, chains and handcuffs and the filthy conditions the inmates lived in. However, it was not until 1828 that the newly appointed Commissioners in Lunacy were empowered to license and supervise private asylums.

The Lunacy Act 1845 was an important landmark in the treatment of the mentally ill, as it explicitly changed the status of mentally ill people to patients who required treatment. The Act created the Lunacy Commission, headed by Lord Shaftesbury, to focus on lunacy legislation reform.[33] The commission was made up of eleven Metropolitan Commissioners who were required to carry out the provisions of the Act;[34] the compulsory construction of asylums in every county, with regular inspections on behalf of the Home Secretary. All asylums were required to have written regulations and to have a resident qualified physician.[35] A national body for asylum superintendents - the Medico-Psychological Association - was established in 1866 under the Presidency of William A. F. Browne, although the body appeared in an earlier form in 1841.[36]

In 1838, France enacted a law to regulate both the admissions into asylums and asylum services across the country. Édouard Séguin developed a systematic approach for training individuals with mental deficiencies,[37] and, in 1839, he opened the first school for the severely "retarded". His method of treatment was based on the assumption that the mentally deficient did not experience disease.[38]

In the United States, the erection of state asylums began with the first law for the creation of one in New York, passed in 1842. The Utica State Hospital was opened approximately in 1850. The creation of this hospital, as of many others, was largely the work of Dorothea Lynde Dix, whose philanthropic efforts extended over many states, and in Europe as far as Constantinople. Many state hospitals in the United States were built in the 1850s and 1860s on the Kirkbride Plan, an architectural style meant to have curative effect.[39]

At the turn of the century, England and France combined had only a few hundred individuals in asylums.[40] By the late 1890s and early 1900s, this number had risen to the hundreds of thousands. However, the idea that mental illness could be ameliorated through institutionalization was soon disappointed.[41] Psychiatrists were pressured by an ever-increasing patient population.[41] The average number of patients in asylums kept on growing.[41] Asylums were quickly becoming almost indistinguishable from custodial institutions,[42] and the reputation of psychiatry in the medical world had hit an extreme low.[43]

Scientific advances

[edit]

In the early 1800s, psychiatry made advances in the diagnosis of mental illness by broadening the category of mental disease to include mood disorders, in addition to disease level delusion or irrationality.[44] The term psychiatry (Greek "ψυχιατρική", psychiatrikē) which comes from the Greek "ψυχή" (psychē: "soul or mind") and "ιατρός" (iatros: "healer") was coined by Johann Christian Reil in 1808.[45][unreliable source?][46] Jean-Étienne Dominique Esquirol, a student of Pinel, defined lypemania as an 'affective monomania' (excessive attention to a single thing). This was an early diagnosis of depression.[44][47]

In 1870, Louis Mayer, a gynecologist in Germany, cured a woman's "melancholia" using a pessary: "It relieved her physical problems and many severe disorders of mood ... application of a Mayer Ring improved her quite considerably."[48] According to The American Journal of Obstetrics and Diseases of Women and Children Mayer reportedly decried the "neglect of the investigation of the relations between mental and sexual diseases of women in German insane hospitals".[49]

The 20th century introduced a new psychiatry into the world. Different perspectives of looking at mental disorders began to be introduced. The career of Emil Kraepelin reflects the convergence of different disciplines in psychiatry.[50] Kraepelin initially was very attracted to psychology and ignored the ideas of anatomical psychiatry.[50] Following his appointment to a professorship of psychiatry and his work in a university psychiatric clinic, Kraepelin's interest in pure psychology began to fade and he introduced a plan for a more comprehensive psychiatry.[51] Kraepelin began to study and promote the ideas of disease classification for mental disorders, an idea introduced by Karl Ludwig Kahlbaum.[52] The initial ideas behind biological psychiatry, stating that the different mental disorders were all biological in nature, evolved into a new concept of "nerves" and psychiatry became a rough approximation of neurology and neuropsychiatry.[53] However, Kraepelin was criticized for considering schizophrenia as a biological illness in the absence of any detectable histologic or anatomic abnormalities.[54]: 221 While Kraepelin tried to find organic causes of mental illness, he adopted many theses of positivist medicine, but he favoured the precision of nosological classification over the indefiniteness of etiological causation as his basic mode of psychiatric explanation.[55]

Following Sigmund Freud's pioneering work, ideas stemming from psychoanalytic theory also began to take root in psychiatry.[56] The psychoanalytic theory became popular among psychiatrists because it allowed the patients to be treated in private practices instead of warehoused in asylums.[56] Freud resisted subjecting his theories to scientific testing and verification, as did his followers.[57] As evidence-based investigations in cognitive psychology led to treatments like cognitive behavioral therapy, many of Freud's ideas appeared to be unsupported or contradicted by evidence.[57] By the 1970s, the psychoanalytic school of thought had become marginalized within the field.[56]

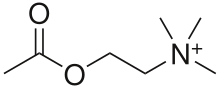

Biological psychiatry reemerged during this time. Psychopharmacology became an integral part of psychiatry starting with Otto Loewi's discovery of the neuromodulatory properties of acetylcholine; thus identifying it as the first-known neurotransmitter.[58] Neuroimaging was first utilized as a tool for psychiatry in the 1980s.[59] The discovery of chlorpromazine's effectiveness in treating schizophrenia in 1952 revolutionized treatment of the disorder,[60] as did lithium carbonate's ability to stabilize mood highs and lows in bipolar disorder in 1948.[61] Psychotherapy was still utilized, but as a treatment for psychosocial issues.[62] In the 1920s and 1930s, most asylum and academic psychiatrists in Europe believed that manic depressive disorder and schizophrenia were inherited, but in the decades after World War II, the conflation of genetics with Nazi racist ideology thoroughly discredited genetics.[63]

Now, genetics are once again thought by some prominent researchers to play a large role in mental illness.[58][64] The genetic and heritable proportion of the cause of five major psychiatric disorders found in family and twin studies is 81% for schizophrenia, 80% for autism spectrum disorder, 75% for bipolar disorder, 75% for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and 37% for major depressive disorder.[65] Geneticist Müller-Hill is quoted as saying "Genes are not destiny, they may give an individual a pre-disposition toward a disorder, for example, but that only means they are more likely than others to have it. It (mental illness) is not a certainty.”[66][unreliable medical source?] Molecular biology opened the door for specific genes contributing to mental disorders to be identified.[58]

Deinstitutionalization

[edit]Asylums: Essays on the Social Situation of Mental Patients and Other Inmates (1961), written by sociologist Erving Goffman,[67][68][better source needed] examined the social situation of mental patients in the hospital.[69] Based on his participant observation field work, the book developed the theory of the "total institution" and the process by which it takes efforts to maintain predictable and regular behavior on the part of both "guard" and "captor". The book suggested that many of the features of such institutions serve the ritual function of ensuring that both classes of people know their function and social role, in other words of "institutionalizing" them. Asylums was a key text in the development of deinstitutionalisation.[70] At the same time, academic psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Thomas Szasz began publishing articles and books that were highly critical of psychiatry and involuntary treatment, including his best-known work The Myth of Mental Illness in 1961.

In 1963, US president John F. Kennedy introduced legislation delegating the National Institute of Mental Health to administer Community Mental Health Centers for those being discharged from state psychiatric hospitals.[71] Later, though, the Community Mental Health Centers focus shifted to providing psychotherapy for those with acute but less serious mental disorders.[71] Ultimately there were no arrangements made for actively following and treating severely mentally ill patients who were being discharged from hospitals.[71] Some of those with mental disorders drifted into homelessness or ended up in prisons and jails.[71][72] Studies found that 33% of the homeless population and 14% of inmates in prisons and jails were already diagnosed with a mental illness.[71][73]

In 1973, psychologist David Rosenhan published the Rosenhan experiment, a study with results that led to questions about the validity of psychiatric diagnoses.[74] Critics such as Robert Spitzer placed doubt on the validity and credibility of the study, but did concede that the consistency of psychiatric diagnoses needed improvement.[75] Spitzer went on to chair the writing of the third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, which aimed to improve reliability by emphasizing measurable symptoms.

Psychiatry, like most medical specialties, has a continuing, significant need for research into its diseases, classifications and treatments.[76] Psychiatry adopts biology's fundamental belief that disease and health are different elements of an individual's adaptation to an environment.[77] But psychiatry also recognizes that the environment of the human species is complex and includes physical, cultural, and interpersonal elements.[77] In addition to external factors, the human brain must contain and organize an individual's hopes, fears, desires, fantasies and feelings.[77] Psychiatry's difficult task is to bridge the understanding of these factors so that they can be studied both clinically and physiologically.[77]

See also

[edit]- History of child and adolescent psychiatry

- History of psychiatric institutions

- History of neurology

- History of psychology

- History of neuropsychology

- History of neurophysiology

References

[edit]- ^ Vipassana and Psychiatry (English) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mn41tTuym0M

- ^ Andrew Scull. Cultural Sociology of Mental Illness: An A-to-Z Guide, Volume 1. SAGE Publications. p. 386.

- ^ David Levinson; Laura Gaccione (1997). Health and Illness: A Cross-cultural Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 42.

- ^ Koenig, Harold G. (2009). Faith and Mental Health: Religious Resources for Healing. Templeton Foundation Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-1-59947-078-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g Elkes, A. & Thorpe, J.G. (1967). A Summary of Psychiatry. London: Faber & Faber, p. 13.

- ^ a b Shorter 1997, p. 1.

- ^ Burton, Robert (1881). The Anatomy of Melancholy: What it is with All the Kinds, Causes, Symptoms, Prognostics, and Several Cures of it: in Three Partitions, with Their Several Sections, Members and Subsections Philosophically, Medicinally, Historically Opened and Cut Up. London: Chatto & Windus. pp. 22, 24. OL 3149647W.

- ^ Miller, Andrew C (December 2006). "Jundi-Shapur, bimaristans, and the rise of academic medical centres". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 99 (12): 615–617. doi:10.1177/014107680609901208. PMC 1676324. PMID 17139063. Archived from the original on 1 February 2013. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ^ Youssef, H. A., Youssef, F. A., & Dening, T. R. (1996). Evidence for the existence of schizophrenia in medieval Islamic society. History of Psychiatry, 7(25), 055–62. doi:10.1177/0957154x9600702503

- ^ Namazi, Mohamed Reza (November 2001). "Avicenna, 980-1037". American Journal of Psychiatry. 158 (11): 1796. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.158.11.1796. PMID 11691684.

- ^ Shoja, Mohammadali M.; Tubbs, R. Shane (February 2007). "The disorder of love in the Canon of Avicenna (A.D. 980-1037)". American Journal of Psychiatry. 164 (2): 228–229. doi:10.1176/ajp.2007.164.2.228. PMID 17267784.

- ^ Safavi-Abbasi, S; Brasiliense, LB; Workman, RK; Talley, MC; Feiz-Erfan, I; Theodore, N; Spetzler, RF; Preul, MC (July 2007). "The fate of medical knowledge and the neurosciences during the time of Genghis Khan and the Mongolian Empire". Neurosurgical Focus. 23 (1): E13. doi:10.3171/FOC-07/07/E13. PMID 17961058. S2CID 8405572.

- ^ a b Shorter 1997, p. 4.

- ^ a b c Tillack-Graf, Anne-Kathleen (2015). "Thomas R. Müller: Wahn und Sinn. Patienten, Ärzte, Personal und Institutionen der Psychiatrie in Sachsen vom Mittelalter bis zum Ende des 20. Jahrhunderts". History of Psychiatry (book review). 26 (4): 498–499. doi:10.1177/0957154X15605782d. ISSN 0957-154X. S2CID 20151680.

- ^ Allderidge, Patricia (1979). "Management and Mismanagement at Bedlam, 1547–1633". In Webster, Charles (ed.). Health, Medicine and Mortality in the Sixteenth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 145. ISBN 9780521226431.

- ^ Stevenson, Christine (1997). "The Architecture of Bethlem at Moorfields". In Jonathan Andrews; Asa Briggs; Roy Porter; Penny Tucker; Keir Waddington (eds.). History of Bethlem. London & New York: Routledge. p. 51. ISBN 978-0415017732.

- ^ Porter, Roy (2006) [1987]. Madmen: A Social History of Madhouses, Mad-Doctors & Lunatics (Ill. ed.). Stroud: Tempus. ISBN 9780752437309.

- ^ Winston, Mark (1994). "The Bethel at Norwich: An Eighteenth-Century Hospital for Lunatics". Medical History. 38 (1): 27–51. doi:10.1017/s0025727300056039. PMC 1036809. PMID 8145607.

- ^ Abrams, Howard Meyers, ed. (1999) The Norton Anthology of English Literature; Vol. 1; 7th ed. New York: W. W. Norton & Co Inc. ISBN 978-0-393-97487-4

- ^ Shorter 1997, p. 5.

- ^ "The Bethel Hospital". Norwich HEART. Archived from the original on 13 November 2011. Retrieved 3 June 2015.

- ^ Laffey P (2003). "Psychiatric therapy in Georgian Britain". Psychological Medicine. 33 (7): 1285–1297. doi:10.1017/S0033291703008109. PMID 14580082. S2CID 13162025.

- ^ Shorter 1997, p. 9.

- ^ Weiner DB (September 1979). "The apprenticeship of Philippe Pinel: a new document, "observations of Citizen Pussin on the insane"". Am J Psychiatry. 136 (9): 1128–34. doi:10.1176/ajp.136.9.1128. PMID 382874.

- ^ Bukelic, Jovan (1995). "2". In Mirjana Jovanovic (ed.). Neuropsihijatrija za III razred medicinske skole (in Serbian) (7th ed.). Belgrade: Zavod za udzbenike i nastavna sredstva. p. 7. ISBN 978-86-17-03418-2.

- ^ Gerard DL (1998). "Chiarugi and Pinel considered: Soul's brain/person's mind". J Hist Behav Sci. 33 (4): 381–403. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1520-6696(199723)33:4<381::AID-JHBS3>3.0.CO;2-S.[dead link]

- ^ Cherry, Charles L. (1989), A Quiet Haven: Quakers, Moral Treatment, and Asylum Reform, London & Toronto: Associated University Presses

- ^ Digby, Anne (1983), Madness, Morality and Medicine: A Study of the York Retreat, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- ^ Glover, Mary R. (1984), The Retreat, York: An Early Experiment in the Treatment of Mental Illness, York: Ebor Press

- ^ a b Borthwick, Annie; Holman, Chris; Kennard, David; McFetridge, Mark; Messruther, Karen; Wilkes, Jenny (2001). "The relevance of moral treatment to contemporary mental health care". Journal of Mental Health. 10 (4): 427–439. doi:10.1080/09638230124277. S2CID 218906106.

- ^ Suzuki A (January 1995). "The politics and ideology of non-restraint: the case of the Hanwell Asylum". Medical History. 39 (1): 1–17. doi:10.1017/s0025727300059457. PMC 1036935. PMID 7877402.

- ^ Edited by: Bynum, W.F.;Porter, Roy;Shepherd, Michael (1988) The Anatomy of Madness: Essays in the history of psychiatry. Vol.3. The Asylum and its psychiatry. Routledge. London EC4

- ^ Unsworth, Clive. "Law and Lunacy in Psychiatry's 'Golden Age'", Oxford Journal of Legal Studies. Vol. 13, No. 4. (Winter, 1993), pp. 482.

- ^ Roberts, Andrew. "The Lunacy Commission; 5.1.1 1845 LUNACY AND ASSOCIATED ACTS". studymore.org.uk.

- ^ Wright, David: "Mental Health Timeline", 1999

- ^ Shorter 1997, pp. 34, 41.

- ^ King, D. Brett; Viney, Wayne; Woody, William Douglas (2007). A History of Psychology: Ideas and Context (4 ed.). Allyn & Bacon. p. 214. ISBN 9780205512133.

- ^ "Edouard Seguin (American psychiatrist)". Encyclopædia Britannica. 12 June 2013.

- ^ Yanni, Carla (2007). The Architecture of Madness: Insane Asylums in the United States. Minneapolis: Minnesota University Press. ISBN 978-0-8166-4939-6.

- ^ Shorter 1997, p. 34.

- ^ a b c Shorter 1997, p. 46.

- ^ Rothman, D.J. (1990). The Discovery of the Asylum: Social Order and Disorder in the New Republic. Boston: Little Brown, p. 239. ISBN 978-0-316-75745-4

- ^ Shorter 1997, p. 65.

- ^ a b Borch-Jacobsen, Mikkel (7 October 2010). "Which came first, the condition or the drug?". London Review of Books. 32 (19): 31–33.

Bipolarity in the modern sense could not have emerged until it became possible to identify mood disorders without delirium or intellectual disorders; in other words, it required a profound redefinition of what had until then been understood as madness or insanity. This development started at the beginning of the 19th century with Esquirol's 'affective monomanias' (notably 'lypemania', the first elaboration of what was to become our modern depression)

- ^ Naragon, Steve (11 July 2010). "Johann Christian Reil (1759-1813)". Archived from the original on 28 May 2010. Retrieved 3 June 2015.

- ^ Marneros A (July 2008). "Psychiatry's 200th birthday". British Journal of Psychiatry. 193 (1): 1–3. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.108.051367. PMID 18700209.

- ^ Mania: A Short History of Bipolar Disorder, David Healy, Johns Hopkins Biographies of Disease series

- ^ Shorter, Edward (2008). Before Prozac: The Troubled History of Mood Disorders in Psychiatry. Oxford University Press.

- ^ "Psychical Disturbances in Women". The American Journal of Obstetrics and Diseases of Women and Children. 26: 697. 1892.

- ^ a b Shorter 1997, p. 101.

- ^ Shorter 1997, pp. 102–103.

- ^ Shorter 1997, p. 103.

- ^ Shorter 1997, p. 114.

- ^ Cohen, Bruce (2003). Theory and practice of psychiatry. Oxford University Press. p. 221. ISBN 978-0-19-514937-1.

- ^ Thiher, Allen (2000). Revels in Madness: Insanity in Medicine and Literature. University of Michigan Press. p. 228. ISBN 978-0-472-11035-3.

- ^ a b c Shorter 1997, p. 145.

- ^ a b The History of Psychiatry (interview with Dr. Jeffrey Lieberman)

- ^ a b c Shorter 1997, p. 246.

- ^ Shorter 1997, p. 270.

- ^ Turner T (2007). "Unlocking psychosis". BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 334 (suppl): s7. doi:10.1136/bmj.39034.609074.94. PMID 17204765. S2CID 33739419.

- ^ Cade JFJ. "Lithium salts in the treatment of psychotic excitement". Med J Aust. 1949 (36): 349–352.

- ^ Shorter 1997, p. 239.

- ^ Eisenberg L, Guttmacher LB (August 2010). "Were we all asleep at the switch? A personal reminiscence of psychiatry from 1940 to 2010". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 122 (2): 89–102. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2010.01544.x. PMID 20618173. S2CID 40941250.

- ^ Arnedo J, Svrakic DM, Del Val C, Romero-Zaliz R, Hernández-Cuervo H, Fanous AH, Pato MT, Pato CN, de Erausquin GA, Cloninger CR, Zwir I (February 2015). "Uncovering the hidden risk architecture of the schizophrenias: confirmation in three independent genome-wide association studies". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 172 (2): 139–53. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.14040435. PMID 25219520.

- ^ Cross-Disorder Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium (September 2013). "Genetic relationship between five psychiatric disorders estimated from genome-wide SNPs". Nature Genetics. 45 (9): 984–995. doi:10.1038/ng.2711. PMC 3800159. PMID 23933821.

- ^ Comeau, Sylvain (6 May 2004). "Geneticist Müller-Hill raises spectre of Nazi experiments". Concordia's Thursday Report. Concordia University.

- ^ Goffman, Erving (1961). Asylums: essays on the social situation of mental patients and other inmates. Anchor Books. ISBN 9780385000161.

- ^ Roberts, Andrew. "Extracts from Erving Goffman: A Middlesex University resource". Retrieved 8 November 2010.

- ^ Weinstein, Raymond M. (1982). "Goffman's Asylums and the Social Situation of Mental Patients" (PDF). Orthomolecular Psychiatry. 11 (4): 267–274.

- ^ Mac Suibhne, Séamus (7 October 2009). "Asylums: Essays on the Social Situation of Mental Patients and other Inmates". BMJ. 339: b4109. doi:10.1136/bmj.b4109. S2CID 220087437.

- ^ a b c d e Shorter 1997, p. 280.

- ^ Slovenko R (2003). "The transinstitutionalization of the mentally ill". Ohio University Law Review. 29 (3): 641–60. PMID 15868685.

- ^ Torrey, E.F. (1988). Nowhere to Go: The Tragic Odyssey of the Homeless Mentally Ill. New York: Harper and Row, pp.25-29, 126-128. ISBN 978-0-06-015993-1

- ^ Rosenhan DL (1973). "On being sane in insane places". Science. 179 (4070): 250–258. Bibcode:1973Sci...179..250R. doi:10.1126/science.179.4070.250. PMID 4683124. S2CID 146772269.

- ^ Spitzer RL, Lilienfeld SO, Miller MB (2005). "Rosenhan revisited: The scientific credibility of Lauren Slater's pseudopatient diagnosis study". Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 193 (11): 734–739. doi:10.1097/01.nmd.0000185992.16053.5c. PMID 16260927. S2CID 3152822.

- ^ Lyness 1997, p. 16.

- ^ a b c d Guze 1992, p. 130.

Cited texts

[edit]- Guze SB (1992). Why Psychiatry Is a Branch of Medicine. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-507420-8. OCLC 25315637.

- Lyness JM (1997). Psychiatric Pearls. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis Company. ISBN 978-0-8036-0280-9. OCLC 807453406.

- Shorter, E (1997), A History of Psychiatry: From the Era of the Asylum to the Age of Prozac, New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., ISBN 978-0-471-24531-5

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

Further reading

[edit]- Jeffrey A. Lieberman; Ogi Ogas (2016). Shrinks: The Untold Story of Psychiatry. Little, Brown. ISBN 978-0316278980.