History of union busting in the United States

The history of union busting in the United States dates back to the Industrial Revolution in the 19th century. The Industrial Revolution produced a rapid expansion in factories and manufacturing capabilities. As workers moved from farms to factories, mines and other hard labor, they faced harsh working conditions such as long hours, low pay and health risks. Children and women worked in factories and generally received lower pay than men. The government did little to limit these conditions. Labor movements in the industrialized world developed and lobbied for better rights and safer conditions. Shaped by wars, depressions, government policies, judicial rulings, and global competition, the early years of the battleground between unions and management were adversarial and often identified with aggressive hostility. Contemporary opposition to trade unions known as union busting started in the 1940s, and continues to present challenges to the labor movement. Union busting is a term used by labor organizations and trade unions to describe the activities that may be undertaken by employers, their proxies, workers and in certain instances states and governments usually triggered by events such as picketing, card check, worker organizing, and strike actions.[1] Labor legislation has changed the nature of union busting, as well as the organizing tactics that labor organizations commonly use.

Strikebreaking and union busting, 1870s–1935

[edit]

Hiring agencies specialising in anti-union practices have been an option available to employers from the bloody strikes of the last quarter of the nineteenth century, until today.[2]

Working with owner John D. Rockefeller, Charles Pratt's Astral Oil Works in 1874 began to buy refineries in Brooklyn to decrease competition. Around this time, the coopers' union opposed Pratt's efforts to cut back on certain manual operations, as they were the craftsmen who made the barrels that held the oil. Pratt busted the union, and his strategies for breaking up the organization were adopted by other refineries.[3]

Creative methods of union busting have been around for a long time. In 1907, Morris Friedman reported that a Pinkerton agent who had infiltrated the Western Federation of Miners managed to gain control of a strike relief fund, and attempted to exhaust that union's treasury by awarding lavish benefits to strikers.[4] However, many attacks against unions have used force of one sort or another, including police action, military force, or recruiting goon squads.

Physical attacks against unions

[edit]Unions such as the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) were devastated by the Palmer Raids, carried out as part of the First Red Scare. The Everett Massacre (also known as Bloody Sunday) was an armed confrontation between local authorities and IWW members which took place in Everett, Washington on Sunday, November 5, 1916. Later, communist-led unions were isolated or destroyed and their activists purged with the assistance of other union organizations during the Second Red Scare.

In May 1886 the Knights of Labor were demonstrating in the Haymarket Square in Chicago, demanding an eight-hour day in all trades. When police arrived, an unknown person threw a bomb into the crowd, killing one person and injuring several others. "In a trial marked by prejudice and hysteria" a court sentenced seven anarchists, six of them German-speaking, to death - with no evidence linking them to the bomb.[5]

Strikes also took place that same month (May 1886) in other cities, including in Milwaukee, where seven people died when Wisconsin Governor Jeremiah M. Rusk ordered state-militia troops to fire upon thousands of striking workers who had marched to the Milwaukee Iron Works Rolling Mill in Bay View, on Milwaukee's south side.

In 1914 one of the most bitter labor conflicts in American history took place at a mining colony in Colorado called Ludlow. After workers went on strike in September 1913 with grievances ranging from requests for an eight-hour day to allegations of subjugation, Colorado governor Elias Ammons called in the National Guard in October 1913. That winter, Guardsmen made 172 arrests.[a][6]

The strikers began to fight back, killing four mine guards and firing into a separate camp where strikebreakers lived. When the body of a strikebreaker was found nearby, the National Guard's General Chase ordered the tent colony destroyed in retaliation.[6]

"On Monday morning, April 20, two dynamite bombs were exploded, in the hills above Ludlow ... a signal for operations to begin. At 9 am a machine gun began firing into the tents [where strikers were living], and then others joined."[6] One eyewitness reported: "The soldiers and mine guards tried to kill everybody; anything they saw move".[6] That night the National Guard rode down from the hills surrounding Ludlow and set fire to the tents. Twenty-six people, including two women and eleven children, were killed.[7]

Union busting with police and military force

[edit]For approximately 150 years, union organizing efforts and strikes have been periodically opposed by police, security forces, National Guard units, special police forces such as the Coal and Iron Police, and/or use of the United States Army. Significant incidents have included the Haymarket Riot and the Ludlow massacre. The Homestead struggle of 1892, the Pullman walkout of 1894, and the Colorado Labor Wars of 1903 are examples of unions destroyed or significantly damaged by the deployment of military force. In all three examples, a strike became the triggering event.

- Pinkertons and militia at Homestead, 1892 – One of the first union busting agencies was the Pinkerton National Detective Agency, which came to public attention as the result of a shooting war that broke out between strikers and three hundred Pinkerton agents during the Homestead Strike of 1892. When the Pinkerton agents were withdrawn, state militia forces were deployed. The militia repulsed attacks on the Carnegie Steel plant, and prevented violence against strikebreakers crossing picket lines, causing a decisive defeat of the strike, and ended the power of the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers at the Homestead plant.

- Federal troops end the railroad blockades by the American Railway Union, 1894 – During the Pullman Strike, the American Railway Union (ARU), out of union solidarity, called out its members according to the principle of industrial unionism. Their actions in blocking the movement of railroad trains were illegal but successful, until twenty thousand federal troops were called out to ensure that trains carrying US mail could travel freely. Once the trains ran, the strike ended.

- National Guard in the Colorado Labor Wars, 1903 – The Colorado National Guard, an employers' organization called the Citizens' Alliance, and the Mine Owners' Association teamed together to eject the Western Federation of Miners from mining camps throughout Colorado during the Colorado Labor Wars.

Strikebreaking by governmental injunction

[edit]In May 1895, in the case of In re Debs, the Supreme Court unanimously upheld the right of the federal government to use injunctions to end labor strikes.

The case stemmed from an injunction against Eugene Debs, president of the American Railway Union, and other strike leaders during the Pullman Strike of 1894. President Grover Cleveland sided with the Pullman Company during the strike, and Cleveland's attorney general Richard Olney sought a court order to end the strike from federal judge Peter S. Grosscup, whom he knew to hold anti-union sentiments. In July 1894, Grosscup issued an injunction, described as an "omnibus injunction" due to its wide scope, that forbade Debs and other union officials "from in any way or manner interfering with, hindering, obstructing or stopping" the railroads entering Chicago, as well as from communicating with their subordinates in the union. In July 1894, Debs and four other union leaders were arrested and charged with violating the injunction. In December 1894, US circuit court judge William A. Woods found Debs and the other union leaders to be in contempt of court for violating the injunction and sentenced them to prison terms ranging from three to six months.[8][9]

The practice of strikebreaking by governmental injunction continued until the passage of the Norris-La Guardia Act in 1932, which prohibited federal courts from issuing injunctions against nonviolent labor disputes, including strikes, picketing, and boycotts by labor unions.[10]

Anatomy of a corporate union buster

[edit]Corporations Auxiliary Company, a union buster during the first half of the 20th century, would tell employers,

Our man will come to your factory and get acquainted... If he finds little disposition to organize, he will not encourage organization, but will engineer things so as to keep organization out. If, however, there seems a disposition to organize he will become the leading spirit and pick out just the right men to join. Once the union is in the field its members can keep it from growing if they know how, and our man knows how. Meetings can be set far apart. A contract can at once be entered into with the employer, covering a long period, and made very easy in its terms. However, these tactics may not be good, and the union spirit may be so strong that a big organization cannot be prevented. In this case our man turns extremely radical. He asks for unreasonable things and keeps the union embroiled in trouble. If a strike comes, he will be the loudest man in the bunch, and will counsel violence and get somebody in trouble. The result will be that the union will be broken up.[11]

In the period 1933 to 1936, Corporations Auxiliary Company had 499 corporate clients.[12]

College students as strikebreakers in the Interborough Rapid Transit strike of 1905

[edit]Following a walk out of subway workers, management of the trains Interborough Rapid Transit in New York City appealed to university students to volunteer as motormen, conductors, ticket sellers and ticket choppers. Stephen Norword discusses the phenomenon of students as strikebreakers in early 20th Century North America: "Throughout the period between 1901 and 1923, college students represented a major, and often critically important source of strikebreakers in a wide range of industries and services. ... Collegians deliberately volunteered their services as strikebreakers and were the group least likely to be swayed by the pleas of strikers and their sympathizers that they were doing something wrong."[13]

Jack Whitehead, the first "King of Strike Breakers"

[edit]There were a significant number of strikes during the 1890s and very early 1900s. Strikebreaking by recruiting massive numbers of replacement workers became a significant activity.

Jack Whitehead saw opportunity in labor struggles; while other workers were attempting to organize unions, he walked away from his union to organize an army of strikebreakers. Whitehead was the first to be called "King of the Strike Breakers"; by deploying his private workforce during strikes of steelworkers in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and Birmingham, Alabama, he became wealthy. By demonstrating how lucrative strikebreaking could be, Whitehead inspired a host of imitators.[14]

James Farley inherits the strikebreaker title

[edit]After Whitehead, men like James A. Farley and Pearl Bergoff turned union busting into a substantial industry. Farley began his strikebreaking career in 1895, and opened a detective agency in New York City in 1902. In addition to detective work, Farley accepted industrial assignments, specializing in breaking strikes of streetcar drivers.[15] Farley hired his men based in part upon courage and toughness, and in some strikes they openly carried firearms. They were paid more than the strikers had been. Farley was credited with a string of successful strikebreaking actions, employing hundreds, and sometimes thousands of strikebreakers. Farley was sometimes paid as much as three hundred thousand dollars for breaking a strike, and by 1914 he had taken in more than ten million dollars. Farley claimed that he had defeated thirty-five strikes in a row. But he suffered from tuberculosis, and as he faced death, he declared that he turned down the job of breaking a streetcar strike in Philadelphia because this time, "the strikers were in the right."[16]

Bergoff Brothers Strike Service and Labor Adjusters

[edit]Pearl Bergoff also began his strikebreaking career in New York City, working as a spotter on the Metropolitan Street Railway in Manhattan. His job was to watch conductors, making certain that they recorded all of the fares that they accepted. In 1905 Bergoff started the Vigilant Detective Agency of New York City. Within two years his brothers joined the lucrative business, and the name was changed to the Bergoff Brothers Strike Service and Labor Adjusters. Bergoff's early strikebreaking actions were characterized by extreme violence. A 1907 strike of garbage cart drivers resulted in numerous confrontations between strikers and the strikebreakers, even when protected by police escorts. Strikers sometimes pelted the strikebreakers with rocks, bottles, and bricks launched from tenement rooftops.[17]

In 1909, the Pressed Steel Car Company at McKees Rocks, Pennsylvania fired forty men, and eight thousand employees walked out under the banner of the Industrial Workers of the World. Bergoff's agency hired strikebreaking toughs from the Bowery, and shipped vessels filled with unsuspecting immigrant workers directly into the strike zone. Other immigrant strikebreakers were delivered in boxcars, and were not fed during a two-day period. Later they worked, ate, and slept in a barn with two thousand other men. Their meals consisted of cabbage and bread.[18]

There were violent confrontations between strikers and strikebreakers, but also between strikebreakers and guards when the terrified workers demanded the right to leave. An Austro-Hungarian immigrant who managed to escape told his government that workers were being held against their will, resulting in an international incident. In addition to kidnapping, strikebreakers complained of deception, broken promises about wages, and tainted food.[19]

During federal hearings, Bergoff explained that "musclemen" under his employ would "get... any graft that goes on", suggesting that was to be expected "on every big job".[19] Other testimony indicated that Bergoff's "right-hand man", described as "huge in stature, weighing perhaps 240 pounds", surrounded himself with thirty-five guards who intimidated and fleeced the strikebreakers, locking them into a boxcar prison with no sanitation facilities when they defied orders.[20]

At the end of August a gun battle erupted, leaving six dead, six dying, and fifty wounded. Public sympathy began to swing away from the company, and toward the strikers. Early in September the company acknowledged defeat and negotiated with the strikers. Twenty-two had died in the strike. But Bergoff's business was not hurt by the defeat; he boasted of having as many as ten thousand strikebreakers on his payroll.[20] He was getting paid as much as two million dollars per strikebreaking job.[21]

Anti-union vigilantes during the First Red Scare

[edit]Unlike the American Federation of Labor, the Industrial Workers of the World opposed the First World War. The American Protective League (APL) was a pro-war organization formed by wealthy Chicago businessmen. At the height of its power the APL had 250,000 members in 600 cities. In 1918, documents from the APL showed that ten percent of its efforts (the largest of any category) were focused on disrupting the activities of the IWW. The APL burgled and vandalized IWW offices, and harassed IWW members. Such actions were illegal, yet were supported by the Wilson administration.[22]

Spies, "missionaries", and saboteurs

[edit]

Strikebreaking by hiring massive numbers of tough opportunists began to lose favor in the 1920s; there were fewer strikes, resulting in fewer opportunities.[20][23] By the 1930s, agencies began to rely more upon the use of informants and labor spies.

Spy agencies hired to bust unions developed a level of sophistication that could devastate targets. "Missionaries" were undercover operatives trained to use whispering campaigns or unfounded rumors to create dissension on the picket lines and in union halls. The strikers themselves were not the only targets. For example, female missionaries might systematically visit the strikers' wives in the home, relating a sob story of how a strike had destroyed their own families. Missionary campaigns have been known to destroy not only strikes, but unions themselves.[24]

In the 1930s, the Pinkerton Agency employed twelve hundred labor spies, and nearly one-third of them held high level positions in the targeted unions. The International Association of Machinists was damaged when Sam Brady, a veteran Pinkerton operative, held a high enough position in that union that he was able to precipitate a premature strike. All but five officers in a United Auto Workers local in Lansing, Michigan were driven out by Pinkerton agents. The five who remained were Pinkertons. At the Underwood Elliott-Fisher Company plant, the union local was so badly injured by undercover operatives that membership dropped from more than twenty five hundred to fewer than seventy-five.[25]

General strikebreaking methods

[edit]During the period from roughly 1910 to 1914, Robert Hoxie compiled a list of methods used by employers' associations to attack unions. The list was published in 1921, as part of the book Trade Unionism in the United States. These methods include counter organization, inducing union leaders to support management, supporting other pro-business enterprises, refusing to work with pro-union enterprises, obtaining information on unions among others.[26]

Hoxie summarized the underlying theories, assumptions, and attitudes of employers' associations of the period. According to Hoxie, these included the supposition that employers' interests are always identical to society's interests, such that unions should be condemned when they interfere; that the employers' interests are always harmonious with the workers' interests, and unions therefore try to mislead workers; that workers should be grateful to employers, and are therefore ungrateful and immoral when they join unions; that the business is solely the employer's to manage; that unions are operated by non-employees, and they are therefore necessarily outsiders; that unions restrict the right of employees to work when, where, and how they wish; and that the law, the courts, and the police represent absolute and impartial rights and justice, and therefore unions are to be condemned when they violate the law or oppose the police.[27]

Given the proliferation of employers' associations created primarily for the purpose of opposing unions, Hoxie poses counter-questions. For example, if every employer has a right to manage his own business without interference from outside workers, then why hasn't a group of workers at a particular company the right to manage their own affairs without interference from outside employers?[28]

Strikebreaking and union busting, 1936–1947

[edit]Shortly after the landslide victory of Franklin D. Roosevelt in the presidential election of 1936, the Supreme Court in April 1937 handed down a decision in which it concurred with the findings of the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) that the Jones and Laughlin Steel Company had engaged in unfair labor practices, including firing workers "because of their union activity and for the purpose of discouraging membership in the union," and upheld the NLRB's order that the company offer reinstatement with backpay to ten of the fired union workers at the company's steelworks in Aliquippa, Pennsylvania, and post notices that the company would not fire or discriminate against union members or those seeking to join the union.[29]

Later in 1937, during the Little Steel strike, approximately 8,000 striking steel workers were illegally fired from their jobs, more than 1,000 striking workers were arrested, and between 16 and 18 strikers were killed over the course of the strike, including 10 workers who were killed in an incident on Memorial Day that came to be known as the Memorial Day massacre of 1937.[30]

Employers in the United States have had the legal right to permanently replace economic strikers since the Supreme Court's 1937 decision in NLRB v. Mackay Radio & Telegraph Co.[31]

Meanwhile, employers began to demand more subtle and sophisticated union busting tactics, and so the field called "preventive labor relations" was born.[32] The new practitioners were armed with degrees in industrial psychology, management, and labor law. They would use these skills not only to manipulate the provisions of national labor law, but also the emotions of workers seeking to unionize.[33]

Nathan Shefferman (Labor Relations Associates), 1940s–1950s

[edit]After passage of the Wagner Act in 1935, the first nationally known union busting agency was Labor Relations Associates of Chicago, Inc. (LRA) founded in 1939 by Nathan Shefferman, who later in 1961 wrote The Man in the Middle, a guide to union busting, and has been considered the 'founding father' of the modern union avoidance industry.[31] Shefferman had been a member of the original NLRB, and became director of employee relations at Chicago-based Sears, Roebuck and Company. Sears had been engaged in blocking unions from the AFL Retail Clerks union throughout the 1930s. Sears provided $10,000 seed money to launch LRA.[34] In 1957 during hearings conducted by the United States, Congress, and Select Committees on Improper Activities in the Labor and Management Field.[35] Nate Shefferman was questioned by Robert Kennedy and testimony revealed that Teamsters union "top brass" were regularly sent to meet with him. An article written by Victor Riesel for Inside Labor on May 28, 1957[36] reveals that Dave Beck, President of the Teamster's Union in that era, worked closely with Nate Shefferman on many deals not the least of which may have been his influence at Sears to discourage employees from joining the AFL Retail Clerks union which was trying to raid the Teamsters membership to join them instead. An indicator of the close relationship between the Teamster's President David Beck and Shefferman (excerpted from the article): "Beck dispatched Shefferman to Jim Hoffa last year (1956) to offer Hoffa the union's presidency if Hoffa would first help re-elect Beck and then wait 6 months for Beck to resign on grounds of ill health". The article asks "Why did Beck and the multi-million dollar Shefferman work so closely—and on what?"[36]

By the late 1940s, LRA had nearly 400 clients. Shefferman's operatives set up anti-union employee groups called "Vote No" committees, developed ruses to identify pro-union workers, and helped arrange sweetheart contracts with unions that would not challenge management.[37] Consultants from LRA "committed numerous illegal actions, including bribery, coercion of employees and racketeering."[31]

Shefferman built "a daunting business on a foundation of false premises", of which "perhaps the most incredible—and most widely believed—is the myth that companies are at a disadvantage to unions organizationally, legally, and financially during a union-organizing drive." What businesses sought to accomplish through such propaganda was for Congress to amend the Wagner Act.[38]

One of Shefferman's associates defined his technique simply by saying: "We operate the exact way a union does," he said. "But on management's side. We give out leaflets, talk to employees, and organize a propaganda campaign."[39]

Strikebreaking and union busting, 1948–1959

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (September 2020) |

In 1956, Nathan Shefferman defeated a unionizing effort of the Retail Clerks Union at seven Boston-area stores by employing tactics that Walter Tudor, the Sears vice-president for personnel, described as "inexcusable, unnecessary and disgraceful". At a Marion, Ohio, Whirlpool plant, an LRA operative created a card file system which tracked employees' feelings about unions. Many of those he regarded as pro-union were fired. A similar practice took place at the Morton Frozen Foods plant in Webster City, Iowa. An employee recruited by LRA operatives wrote down a list of employees thought to favor a union. Management fired those workers. The list-making employee received a substantial pay increase. When the United Packinghouse Workers of America union was defeated, Shefferman arranged a sweetheart contract with a union that Morton Frozen Foods controlled, with no participation from the workers. From 1949 through 1956, LRA earned nearly $2.5 million providing such anti-union services.[40]

In 1957, the United States Senate Select Committee on Improper Activities in Labor and Management (also known as the McClellan Committee) investigated unions for corruption, and employers and agencies for union busting activities. Labor Relations Associates was found to have committed violations of the National Labor Relations Act of 1935, including manipulating union elections through bribery and coercion, threatening to revoke workers' benefits if they organized, installing union officers who were sympathetic to management, rewarding employees who worked against the union, and spying on and harassing workers.[41] The McClellan Committee believed that "the National Labor Relations Board [was] impotent to deal with Shefferman's type of activity."[42]

Strikebreaking and union busting, 1960–2000

[edit]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (November 2011) |

There is little evidence that employers availed themselves of anti-union services during the 1960s or the early 1970s.[44] However, under a new reading of the Landrum-Griffin Act, the U.S. Department of Labor took action against consulting agencies related to filing of required reports in only three cases after 1966, and between 1968 and 1974 it filed no actions at all. By the late 1970s, consulting agencies had stopped filing reports.

The 1970s and 1980s were an altogether more hostile political and economic climate for organized labor.[31] Meanwhile, a new multi-billion dollar union buster industry, using industrial psychologists, lawyers, and strike management experts, proved skilled at sidestepping requirements of both the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) and Landrum-Griffin in the war against labor unions.[45] In the 1970s the number of consultants, and the scope and sophistication of their activities, increased substantially. As the numbers of consultants increased, the numbers of unions suffering National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) setbacks also increased. Labor's percentage of election wins slipped from 57 percent to 46 percent. The number of union decertification elections tripled, with a 73 percent loss rate for unions.[42]

Labor relations consulting firms began providing seminars on union avoidance strategies in the 1970s.[46] Agencies moved from subverting unions to screening out union sympathizers during hiring, indoctrinating workforces, and propagandizing against unions.[47]

In August 1981, the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization (PATCO) went on strike seeking better pay and working conditions, among other issues. When the striking workers refused to obey a court order to return to work, President Ronald Reagan ordered the Federal Aviation Administration to fire all 11,345 strikers and hire strikebreakers to replace them. While approximately 500 PATCO members were rehired, the vast majority of striking workers were permanently banned from federal employment.[48] In October 1981, PATCO was decertified as a union by the Federal Labor Relations Authority.[49] According to Steve Early of The Boston Globe, "PATCO's destruction ushered in a decade of lost strikes and lockouts, triggered by management demands for pay and benefit givebacks that continue to this day in a wide range of industries."[50]

By the mid-1980s, Congress had investigated, but failed to regulate, abuses by labor relations consulting firms. Meanwhile, while some anti-union employers continued to rely upon the tactics of persuasion and manipulation, other besieged firms launched blatantly aggressive anti-union campaigns. At the dawn of the 21st Century, methods of union busting have recalled similar tactics from the dawn of the 20th Century.[51] The political environment has included the NLRB and the Department of Labor failing to enforce the labor law against companies that repeatedly violate it.[52][53]

Case Farms built its business by recruiting immigrant workers from Guatemala, who endure conditions few Americans would put up with. From 1960 to 2000 the percentage of workers in the United States belonging to a labor union fell from 30% to 13%, almost all of that decline being in the private sector.[54] This is despite an increase in workers expressing an interest in belonging to unions since the early 1980s. (In 2005, more than half of unionized private-sector workers said they wanted a union in their workplace, up from around 30% in 1984.[55]) According to one source—Winner-Take-All Politics: How Washington Made the Rich Richer—and Turned Its Back on the Middle Class, Jacob S. Hacker and Paul Pierson—a change in the political climate in Washington DC starting in the late 1970s "sidelined" the NLRA. Much more aggressive and effective business lobbying meant "few real limits on ... vigorous antiunion activities. ... Reported violations of the NLRA skyrocketed in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Meanwhile, strike rates plummeted, and many of the strikes that did occur were acts of desperation rather than indicators of union muscle."[56]

In neighboring Canada, where the structure of the economy and pro or anti-union sentiment among workers is very similar, unionization was steadier. From 1970 to 2003, union density in the US declined from 23.5 percent to 12.4 percent, while in Canada the loss was much smaller, going from 31.6 percent in 1970 to 28.4 percent in 2003.[57] One difference is that Canadian law allows for card certification and first-contract arbitrations (both features of the proposed Employee Free Choice Act promoted by labor unions in the United States). Canadian law also bans permanent striker replacements, and imposes strong limits on employer propaganda."[58]

According to David Bacon, "Modern unionbusting" employs company-dominated organizations in the workplace to forestall organizing drives.[59]

Strikebreaking and union busting, post-2000

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (March 2024) |

Captive audience techniques

[edit]Common legal tactics used by employers to prevent unionization include forcing employees to attend anti-union meetings, known as captive audience meetings, where pro-union workers are unable to present alternative views; covering the workplace with anti-union posters, banners, or videos; instructing managers to tell workers that they may lose their jobs if they vote to unionize; and having managers hold one-on-one meetings with workers to argue it would be bad for them to vote for a union.[60] Employers' messages frequently focus on themes such as the idea that unions will drive employers out of business, that unions only care about extracting dues payments from workers, and that unionization is unnecessary or futile.[60] Overall, US employers spend more than $400 million per year on union-avoidance consultants to help them prevent employees from forming unions.[61]

As of July 2024, by state law, workers are allowed to voluntarily leave anti-union meetings without employer retaliation in Illinois, Washington State, Oregon, Minnesota, Maine, Connecticut, and New York.[62][63] "Captive audience bans" can be broad - applying in some states to any political or religious topic - and have been challenged in court on the grounds they violate the Free Speech Clause of the federal constitution or that they are pre-empted by federal law.[63]

On November 13, 2024, the National Labor Relations Board ruled that captive audience meeting are illegal throughout the United States.[64][65]

Anti-union corporate training materials

[edit]A number of US corporations have also produced anti-union training materials that have been disseminated to managers or other employees.

In 2018, Amazon distributed a 45-minute union-busting training video to managers at Whole Foods, which it had acquired in 2017, instructing managers to look for warning signs that might indicate "vulnerability to organizing," including use of the term "living wage" and workers showing an “unusual interest in policies, benefits, employee lists, or other company information,” and to immediately escalate potential signs of organizing to general managers.[66]

In January 2022, Target emailed store managers at the company new training documents, instructing managers to look for warning signs of union organizing within their stores, including conversations among workers regarding pay, benefits, job security, or other grievances, and to coordinate with human resources to prevent unionization.[67]

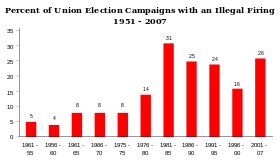

Accusations and complaints by workers of unfair labor practices

[edit]In the early 21st century, employees at a number of prominent US corporations have accused their employers of engaging in illegal union-busting activities.[68] A 2019 report from the Economic Policy Institute found that employers were charged with illegally firing workers in 19.9% of union elections, and with illegally coercing, threatening, or retaliating against workers for supporting a union in 29.6% of union elections.[69] Overall, unfair labor practice charges were filed against employers in 41.5% of NLRB-supervised union elections that took place in 2016 and 2017, and in elections involving more than 60 voters 54.4% of employers were charged with at least one illegal act.[69]

In July 2015, the International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers union filed a complaint with the NLRB against Amazon, alleging that the company engaged in unfair labor practices by surveilling, threatening, and “informing employees that it would be futile to vote for union representation” during a during a union drive in 2014 and 2015 at an Amazon warehouse in Chester, Virginia.[70] In 2016, Amazon settled the complaint with the NLRB, denying any wrongdoing but agreeing to post a list at the warehouse of 22 forms of union-busting behavior that the company promised not to engage in, including threatening workers with the loss of a job or other reprisals if they were union supporters, interrogating workers about the union, or engaging in surveillance of workers while they participated in union activities.[70] In May 2024, workers at an Amazon warehouse in St. Peters, Missouri filed an unfair labor practice charge against the company with the NLRB, accusing the company of using "intrusive algorithms" as part of a surveillance program to deter union organizing at the warehouse.[71] In June 2024, a group of 104 delivery drivers at Amazon's DIL7 facility in Skokie, Illinois, employed by contractor Four Star Express Delivery as part of Amazon's Delivery Service Partner subcontractor program, and organized with the Teamsters Local 704 union, filed unfair labor practice charges with the NLRB against both Amazon and Four Star Express as a single or joint employer, alleging that their employer terminated employees for organizing a union, surveilled workers attempting to organize, implemented a hiring freeze in response to unionization efforts, suppressed pro-union speech on employee message boards, altered terms of employment in response to union activity, and sought to permanently close the DIL7 facility in response to union organizing.[72]

In 2019, the IWW Freelance Journalists Union filed a complaint with the NLRB against Barstool Sports, alleging that Barstool owner David Portnoy had violated federal labor law by threatening retaliation against Barstool employees if they attempted to unionize.[73][74] In January 2020, Barstool reached an informal settlement with the NLRB in which Portnoy agreed to delete a series of tweets he had posted in August 2019 in which he threatened to fire "on the spot" any Barstool employee who contacted a reporter to talk about unionization as well as reposting a 2015 blog article in which he threatened to "smash their little union to smithereens" if Barstool employees attempted to unionize.[75] The settlement also required Barstool to notify employees of their right to unionize and to delete a Twitter account the company had created called "Barstool Sports Union" which had solicited DMs from employees in an apparent attempt to identify union supporters within the company.[74]

In September 2021, workers at Activision-Blizzard with the ABK Workers Alliance filed unfair labor practice charges with the NLRB, alleging that the company threatened workers, told workers they could not discuss wages, hours, or working conditions, and "maintained an overly broad social media policy" and enforced the policy against employees who "engaged in protected concerted activity."[76]

In December 2021, an employee at a Target store in Indianapolis, Indiana named Andrew Stacy filed an unfair labor practice charge with the NLRB, alleging that a manager at the store confiscated union flyers that Stacy was distributing with a co-worker and then interrogated the co-worker about the flyers.[67]

In January 2022, the NewsGuild filed a complaint with the NLRB accusing The New York Times Company of violating federal labor law by adding new paid days off to the company's holiday calendar exclusively for non-union workers,[77] and the New York Times Guild accused the company of making similar changes to the company's bereavement policy, making it applicable only to non-union workers, later the same month.[78][79] In July 2023, the NewsGuild filed a grievance against The New York Times, accusing it of engaging in union-busting by announcing its intention to eliminate its sports section and to instead use non-union workers at The Athletic, which The New York Times acquired in 2022, to cover sports.[80][81]

In August 2022, Trader Joe's announced that it was closing a wine shop it operated in Union Square in New York City.[82] The United Food and Commercial Workers Union (UFCW) alleged that Trader Joe’s closed the wine shop because workers at that location were planning to file for a union election, though the company denies that the store was closed due to unionization activity.[83]

In December 2022, two Tesla workers filed complaints with the NLRB accusing the company of illegally firing them in retaliation for criticizing the company's CEO, Elon Musk, in violation of federal laws protecting speech about working conditions.[84] In February 2023, a group of workers at a Tesla factory in Buffalo, New York, dubbed Gigafactory 2, filed an injunction with the NLRB, accusing the automaker of firing more than 30 workers from the company's Autopilot unit "in retaliation for union activity and to discourage union activity."[85][86] The company, however, denied the allegations, and the complaint was dismissed by the NLRB in November 2023.[87]

In June 2023, a worker at a Lowe's store in New Orleans, Louisiana named Felix Allen was fired after leading a union drive at the store, leading to unfair labor practice charges being filed with the NLRB, accusing the company of multiple violations of labor law in response to a union drive at the store, including surveillance, interrogation of employees, and retaliating against union organizers.[88]

In October 2023, the Association of Flight Attendants-CWA sued SkyWest Airlines, alleging that the company illegally fired two flight attendants as retaliation for engaging in protected union organizing activities and that the company illegally stood up a company union in violation of the Railway Labor Act.[89][90]

In November 2023, workers at eight REI retail stores accused the company of dozens of violations of labor law, including retaliating against pro-union workers, altering working conditions without union consultation, and refusing to bargain in good faith with unions at stores that voted in favor of unionization.[91]

In March 2024, workers at a Mercedes-Benz plant in Vance, Alabama filed charges against the company with the NLRB, accusing the company of illegally disciplining workers at the plant in retaliation for organizing with the United Auto Workers (UAW) labor union.[92] In May 2024, following the loss of a unionization vote at the plant, the UAW filed a formal complaint with the NLRB seeking a new election due to what it called "wanton lawlessness" on the part of Mercedes-Benz in the run up to the election, with the UAW accusing the company of holding anti-union captive audience meetings, targeting pro-union workers for drug tests, and illegally terminating UAW supporters.[93][94]

In May 2024, the Progressive Workers Union (PWU) filed unfair labor practice charges with the NLRB against the Sierra Club, accusing the organization of planning retaliatory firings after a list of 30 workers that the organization planned to fire was circulated that included three members of the union's national unit bargaining team and two members of the union's executive committee.[95][96]

In June 2024, the Communications Workers of America filed an unfair labor practice charge with the NLRB against Lionbridge Technologies, which is contracted to perform QA testing for Activision, alleging that the company fired "substantially all of the approximately 160 employees working at its Boise, ID, worksite" in retaliation for union-related activities, including "protected organizing activities and protected speech when raising issues regarding their working conditions," and accusing the company of having a "documented union-busting track record."[97][98]

In June 2024, workers at Compass Coffee, a Washington, DC–based coffee roaster, filed an unfair labor practice charge against the company with the NLRB, accusing Compass Coffee of hiring 124 additional people, including Liz Brown, a lobbyist for Uber, and Cullen Gilchrist, the CEO and co-founder of Union Kitchen, and of manipulating schedules retroactively to make it appear as though the newly hired employees were eligible to vote in an upcoming union election.[99]

In August 2024, the American Guild of Musical Artists (AGMA) filed unfair labor practice charges against Dallas Black Dance Theatre (DBDT) in Dallas, Texas, alleging practices including unilateral changes to employee benefits and a retaliatory firing on the part of the company, following a unanimous vote by the company's dancers to unionize in May 2024.[100] Shortly thereafter, DBDT fired all of its dancers, which the company claimed was in response to an unspecified video surfacing, but which AGMA President Ned Hanlon characterized as "clearly retaliation for unionizing," leading AGMA to issue a "do not work" order against DBDT in response, which prohibits members of AGMA, Actors' Equity Association, and SAG-AFTRA, among others, from working for DBDT until the order is lifted.[101]

In August 2024, the UAW filed unfair labor practice charges against Donald Trump and Elon Musk, accusing them of illegally threatening to fire striking workers during a livestream on X (formerly Twitter).[102]

Formal charges and rulings by the NLRB

[edit]Multiple accusations have led to formal charges and rulings by the NLRB against US corporations for engaging in illegal anti-union practices.

In May 2012, an NLRB judge overturned the results of a unionization election at a Target store in Valley Stream, New York, and ordered a new vote, finding that Target managers had illegally barred employees from wearing union buttons and distributing fliers, threatened to discipline employees who discussed unionization, and threatened to close the store if the workers voted to unionize.[103]

In April 2019, an NLRB judge found that Lowe’s Home Centers violated the National Labor Relations Act by forbidding workers from discussing their pay.[104]

In May 2019, following a complaint filed by the United Steelworkers in November 2017, an NLRB judge found Kumho Tire had engaged in "pervasive" illegal conduct during a unionization campaign at the company's tire manufacturing plant in Macon, Georgia, with at least 12 managers including the company’s CEO issuing illegal threats to lay off employees or to close the plant if it unionized.[105][106]

In December 2019, the office of NLRB general counsel Peter Robb filed a complaint against Chipotle, accusing the company of firing a worker in New York City in retaliation for trying to organize a union, as well as alleging that a manager threatened to fire workers if they engaged in protected union activities, implying they could face physical violence as a result.[107] In November 2022, the NLRB accused Chipotle of illegally closing a store in Augusta, Maine where workers were in the process of forming a union.[108]

In March 2021, the NLRB ruled that Tesla violated labor law when it fired a union organizer, Richard Ortiz, and when the company's CEO, Elon Musk, posted a tweet that was viewed as threatening to labor organizers within the company, and it ordered Tesla to have Musk delete the anti-union tweet and to reinstate Ortiz and to compensate him for the loss of earnings.[109] In April 2022, the NLRB ruled that Tesla's dress code, which prohibited workers from wearing union logos or insignia, was unlawful,[110] although in November 2023 the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit overturned the NLRB's ruling.[111] In April 2023, the NLRB ruled that Tesla violated labor law by prohibiting workers at an Orlando, Florida service center from discussing pay or raising grievances about working conditions with upper management.[112] In May 2024, an official with the NLRB filed a complaint claiming that Tesla's workplace rule barring workers from using workplace technology for the purposes of "unauthorized solicitating [sic] or promoting" or "creating channels and distribution lists" violated US labor law by illegally discouraging workers at an assembly plant in Buffalo, New York from union organizing.[113][114]

In November 2021, a regional director for the NLRB found that Amazon had violated labor laws at a warehouse in Bessemer, Alabama, including by interrogating, surveilling, and threatening pro-union workers, as well as by setting "overly broad" restrictions on workers' access to the warehouse, during a union drive at the warehouse by the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union.[115] In May 2022 the NLRB accused Amazon CEO Andy Jassy of violating federal labor law during media interviews in 2022 where he said workers are better off without a union,[116] and in May 2024 an NLRB judge ruled that Jassy's comments had indeed violated the law.[117] In December 2023, the NLRB found that Amazon had illegally interrogated warehouse workers in Staten Island, New York, as well prohibiting workers from handing out union literature and confiscating union literature from workers.[118] Overall, as of September 2023, 222 open or settled unfair labor practice charges had been filed against Amazon in 25 states.[119]

In December 2021, an administrative judge with the NLRB found that Cemex Construction Materials had committed more than two dozen unfair labor practices, including threatening, surveilling, and interrogating workers, as well as hiring security guards to intimidate workers in the lead up to a 2019 Teamsters union election.[120] In August 2023, the NLRB affirmed the judge's findings, and used the Cemex case to set a new policy requiring an employer that is found to have interfered with a union election to immediately recognize and bargain with the union, whereas previously a new election would be ordered, thereby partially reviving the Joy Silk doctrine.[120][121]

In January 2022, the NLRB filed a complaint against The New York Times, alleging that the company illegally prevented workers designated as "intern managers" from showing support for a recently formed union of tech workers at the company.[122]

As of February 2023, the NLRB had brought 75 complaints against Starbucks accusing it of more than 1,000 illegal actions.[68] In August 2022, the NRLB ordered Starbucks to reinstate seven employees who were allegedly fired for supporting a Starbucks union campaign at a store in Memphis, Tennessee.[123] The NLRB was granted an injunction to this effect by US District Judge Sheryl Lipman, which was upheld by the Sixth Circuit Court in 2023, though the injunction was later overturned by the Supreme Court in June 2024, in a decision that requires federal courts to apply a stricter standard to similar cases going forward.[124]

In December 2022, the NLRB ruled that Apple illegally interrogated and made coercive statements to retail store workers in Atlanta, Georgia during a union drive.[125] In November 2023, the NLRB filed a complaint against Apple over its practices at a retail store in Towson, Maryland, accusing the company of offering new benefits to non-unionized workers while denying the same benefits to unionized workers at the Towson store with the aim of "discouraging" other employees from unionizing.[126] In May 2024, the NLRB ruled that Apple illegally questioned workers about union matters and confiscated union flyers at its World Trade Center store in New York City in 2022, affirming the findings of an administrative judge in 2023.[127]

In December 2023, the NLRB accused Trader Joe's of illegally firing a worker for supporting a union at a store in Hadley, Massachusetts.[128]

In January 2024, the NLRB accused SpaceX of illegally firing a group of employees who wrote an open letter in June 2022 that was critical of the company's CEO Elon Musk.[129] The following day, SpaceX filed a lawsuit arguing that the structure of the NLRB is unconstitutional.[130] Notably, a number of other companies that have been accused of illegal anti-union activity by the NLRB, including Amazon, Starbucks, and Trader Joe's, have also brought lawsuits arguing that the NLRB is unconstitutional.[131] In response, NLRB general counsel Jennifer Abruzzo accused these companies of bringing their respective lawsuits against the NLRB in retaliation for the agency "trying to hold them accountable for repeatedly violating workers’ rights to organize and collectively bargain through representatives of their free choosing.”[132]

In April 2024, a judge with the NLRB found that U.S. bourbon maker Woodford Reserve, owned by Brown-Forman, undermined unionization efforts at its distillery in Versailles, Kentucky by timing changes in merit pay and vacation policies, as well as handing out bottles of whiskey to workers, in order to influence the outcome of a unionization vote.[133]

In June 2024, the NLRB found that Station Casinos had committed "extensive coercive and unlawful misconduct," including discriminatory work assignments and threatening workers with being fired for supporting unionization, and that these actions "stemmed from a carefully crafted corporate strategy intentionally designed at every step to interfere with employees’ free choice" to unionize with the Culinary Workers Union or not.[134][135] As part of its ruling, the NLRB also issued a remedial bargaining order, requiring Station Casinos to immediately recognize and bargain with the union rather than hold a new election, marking the first time the NLRB had issued such an order following its decision in the Cemex case in August 2023.[134][135][136]

Anti-union legislation

[edit]In May 2023, Florida Governor Ron DeSantis signed into a law a bill that imposed new requirements on public sector unions in Florida, including making it more difficult for unions to collect dues, which was labeled as a "paycheck protection" measure, as well as making it more difficult for unions to remain certified, with unions that cannot demonstrate a 60% membership rate at their workplaces being automatically decertified by the state under the new law.[137]

In May 2024, Alabama Governor Kay Ivey signed into law a bill, known as Senate Bill 231, that bars companies in the state from receiving state-level economic incentives, including grants, loans, and tax credits, if companies voluntarily recognize a workers' union, rather than requiring workers to vote on whether to unionize.[138]

History of labor legislation

[edit]Railway Labor Act, 1926

[edit]The Railway Labor Act[139][140] (RLA) of 1926 was the first major piece of labor legislation passed by Congress. The RLA was amended in 1936 to expand from railroads and cover the emerging airline industry. At UPS, the mechanics, dispatchers, and pilots are the labor groups that are covered by the RLA. It was enacted because Railroad management wanted to keep the trains moving by putting an end to "wildcat" strikes. Railroad workers wanted to make sure they had an opportunity to organize, be recognized as the exclusive bargaining agent in dealing with a company, negotiate new agreements and enforce existing ones. Under the RLA, agreements do not have expiration dates; instead they have amendable dates which are indicated within the agreement.

Wagner Act, 1935

[edit]The National Labor Relations Act (NLRA),[141] often referred to as the Wagner Act, was passed by Congress July 5, 1935. It established the right to organize unions. The Wagner Act was the most important labor law in American history and earned the nickname "labor's bill of rights". It forbade employers from engaging in five types of labor practices: interfering with or restraining employees exercising their right to organize and bargain collectively; attempting to dominate or influence a labor union; refusing to bargain collectively and in "good faith" with unions representing their employees; and, finally, encouraging or discouraging union membership through any special conditions of employment or through discrimination against union or non-union members in hiring. Before the law, employers had liberty to spy upon, question, punish, blacklist, and fire union members. In the 1930s workers began to organize in large numbers. A great wave of work stoppages in 1933 and 1934 included citywide general strikes and factory occupations by workers. Hostile skirmishes erupted between workers bent on organizing unions, and the police and hired security squads backing the interests of factory owners who opposed unions. Some historians maintain that Congress enacted the NLRA primarily to help stave off even more serious—potentially revolutionary—labor unrest. Arriving at a time when organized labor had nearly lost faith in Roosevelt, the Wagner Act required employers to acknowledge labor unions that were favored by a majority of their work forces. The Act established the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), with oversight over union elections and unfair labor practices by employers.[142]

Taft–Hartley Act, 1947

[edit]The Taft–Hartley Act[143] was a major revision of the National Labor Relations Act of 1935 (the Wagner Act) and represented the first major revision of a New Deal act passed by a post-war Congress. In the mid-term elections of 1946, the Republican Party gained majorities in both houses for the first time since 1931. With the Truman administration initially taking no stand on the bill, it passed both houses with strong bipartisan support. In addition to overwhelming Republican support, a clear majority of House Democrats voted for the bill, while Democrats in the Senate split evenly, 21–21.[144]

The Taft–Hartley Act was vehemently denounced by union officials, who dubbed it a "slave labor" bill. Truman vetoed the bill with a strong message to Congress, but despite Truman's all-out effort to stop the veto override, On June 23, 1947, Congress overrode his veto with considerable Democratic support, including 106 out of 177 Democrats in the House, and 20 out of 42 Democrats in the Senate.[145] However, twenty-eight Democratic members of Congress declared it a "new guarantee of industrial slavery".

Management always had the upper hand, of course; they had never lost it. But thanks to Taft–Hartley, the bosses could once again wage their war with near impunity.

Taft–Hartley gave the National Labor Relations Board the power to act against unions engaged in unfair labor practices; previously, the board could only consider unfair practices by employers. It defined specific employer rights which broadened an employer's options during union organizing drives. It banned the closed shop, in which union membership is a precondition of employment at an organized workplace. It allowed state "right to work" laws which prohibit mandatory union dues.

The act required union officials to swear that they were not communists. This provision was overturned by the Supreme Court in 1965.[146]

The act gave the president the power to petition the courts to end a strike if it constitutes a national emergency. Presidents have invoked the Taft–Hartley Act thirty-five times to halt work stoppages in labor disputes; almost all of the instances took place in the late 1940s, 1950s and 1960s, under presidents Truman, Eisenhower, Kennedy, and Johnson, after which the provision fell into disuse. The last two times the emergency provision was invoked were in 1978 by Jimmy Carter and 2002 by George W. Bush.

Landrum–Griffin Act, 1959

[edit]The Landrum–Griffin Act of 1959 is also known as the Labor Management Reporting and Disclosure Act (LMRDA)[147] defined financial reporting requirements for both unions and management organizations. Pursuant to LMRDA Section 203(b) employers are required to disclose the costs of any persuader activity as it regards consultants and potential bargaining unit employees.[148]

Martin J. Levitt's interpretation is as follows:

The law regulates labor unions' internal affairs and union officials' relationships with employers. But the law also required companies to report certain expenditures related to their anti-union activities. Fortunately for union busters, loopholes in the requirements allow management and their agents to ignore the provisions aimed at reforming their behavior.[149] The loopholes require consultants to file if they communicate with employees either for the purpose of persuading them not to join a union, or to gain knowledge about the employees or the union that may be passed on to the employer. However, most consultants accomplish these goals by indirect means, using supervisors and management as their first line of contact with employees. Even before the Act was passed, labor consultants had identified front-line supervisors as the most effective lobbyists for management.[150]

Landrum–Griffin also seeks to prevent consultants from spying on employees or the union. Information is not to be compiled unless it is for the purpose of a specific legal proceeding. According to Martin Levitt, "It is easy for consultants to use this provision as a cover for "all kinds of information gathering".[150]

According to Levitt, "because of Landrum–Griffin's vague language, attorneys are able to directly interfere in the union-organizing process without any reporting requirements. Therefore, "young lawyers run bold anti-union wars and dance all over Landrum–Griffin." The provisions of Landrum–Griffin allowing special rights for lawyers resulted in labor consultants working under the shield of labor attorneys, allowing them to easily evade the intent of the law."[151]

Levitt stated:

With the help of our trusted attorneys, our anti-union activities were carried out [under Landrum-Griffin] in backstage secrecy; meanwhile we gleefully showcased every detail of union finances that could be twisted into implications of impropriety or incompetence.

— Martin Jay Levitt, 1993, Confessions of a Union Buster[150]

See also

[edit]- Anti-union violence in the United States

- Grabow Riot

- Labor spies

- Mohawk Valley formula

- Strike breaking

- Union threat model

- Union wage premium

- Salt (union organizing)

- Martin J. Levitt

Notes

[edit]- ^ As the conflict dragged on, the state of Colorado was unable to pay the salaries of many National Guardsmen. As enlisted men dropped out, mine guards took their places, their uniforms, and their weapons.

References

[edit]- ^ "1981 Strike Leaves Legacy for American Workers". NPR.org.

- ^ From Blackjacks To Briefcases — A History of Commercialized Strikebreaking and Unionbusting in the United States, Robert Michael Smith, 2003, page xiv.

- ^ M. Snyder-Grenier, Ellen (2004). Brooklyn!: An Illustrated History. Temple University Press. p. 154. ISBN 9781592130825.

- ^ The Autobiography of Big Bill Haywood, William D. Haywood, 1929, pages 157-58.

- ^ Tindall and Shi, 1984, p. 829.

- ^ a b c d Kick et al., 2002, p. 263.

- ^ Kick et al., 2002, p. 264.

- ^ Urofsky, Melvin I. (May 19, 2024). "In re Debs". Britannica. Archived from the original on May 31, 2024. Retrieved May 31, 2024.

- ^ Christianson, Stephen G. "In Re Debs: 1895". Encyclopedia.com. Archived from the original on May 29, 2023. Retrieved May 31, 2024.

- ^ "Norris–La Guardia Act | Labor Relations, Unionization & Collective Bargaining". Britannica. Archived from the original on January 19, 2024. Retrieved May 31, 2024.

- ^ Harry Wellington Laidler, Boycotts and the labor struggle economic and legal aspects, John Lane company, 1913, pages 291-292

- ^ John J. Abt, Michael Myerson, Advocate and activist: memoirs of an American communist lawyer, University of Illinois Press, 1993, page 63

- ^ Norwood, Stephen H. (2002). Strikebreaking and Intimidation: Mercenaries and Masculinity in Twentieth-Century America. Chapel Hill, NC, USA: University of North Carolina Press. pp. 15–17. ISBN 978-0-8078-2705-5. OCLC 59489222.

- ^ From Blackjacks To Briefcases — A History of Commercialized Strikebreaking and Unionbusting in the United States, Robert Michael Smith, 2003, page 40.

- ^ From Blackjacks To Briefcases — A History of Commercialized Strikebreaking and Unionbusting in the United States, Robert Michael Smith, 2003, page 41.

- ^ From Blackjacks To Briefcases — A History of Commercialized Strikebreaking and Unionbusting in the United States, Robert Michael Smith, 2003, pages 41-42, 45, 47-48, and 53-54.

- ^ From Blackjacks To Briefcases — A History of Commercialized Strikebreaking and Unionbusting in the United States, Robert Michael Smith, 2003, pages 55-56.

- ^ From Blackjacks To Briefcases — A History of Commercialized Strikebreaking and Unionbusting in the United States, Robert Michael Smith, 2003, pages 58-59.

- ^ a b From Blackjacks To Briefcases — A History of Commercialized Strikebreaking and Unionbusting in the United States, Robert Michael Smith, 2003, pages 59-60.

- ^ a b c From Blackjacks To Briefcases — A History of Commercialized Strikebreaking and Unionbusting in the United States, Robert Michael Smith, 2003, page 61.

- ^ From Blackjacks To Briefcases — A History of Commercialized Strikebreaking and Unionbusting in the United States, Robert Michael Smith, 2003, page 67.

- ^ Information from American Protective League Retrieved March 28, 2007.

- ^ From Blackjacks To Briefcases — A History of Commercialized Strikebreaking and Unionbusting in the United States, Robert Michael Smith, 2003, page 68.

- ^ From Blackjacks To Briefcases — A History of Commercialized Strikebreaking and Unionbusting in the United States, Robert Michael Smith, 2003, pages 88-89.

- ^ From Blackjacks To Briefcases — A History of Commercialized Strikebreaking and Unionbusting in the United States, Robert Michael Smith, 2003, page 88.

- ^ Robert Franklin Hoxie, Lucy Bennett Hoxie, Nathan Fine, Trade Unionism in the United States, D. Appleton and Co., 1921, pages 195-200.

- ^ Robert Franklin Hoxie, Lucy Bennett Hoxie, Nathan Fine, Trade Unionism in the United States, D. Appleton and Co., 1921, pages 195-96.

- ^ Robert Franklin Hoxie, Lucy Bennett Hoxie, Nathan Fine, Trade Unionism in the United States, D. Appleton and Co., 1921, page 198.

- ^ "Cases Adjudged in the Supreme Court of the United States at October Term, 1936 | National Labor Relations Board v. Jones & Laughlin Steel Corp" (PDF). Library of Congress. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 2, 2021. Retrieved July 3, 2024.

- ^ Fong, Benjamin; White, Ahmed (April 14, 2024). "America's Last Violent Strike Has Been Wrongly Forgotten". Jacobin. Archived from the original on April 15, 2024. Retrieved April 25, 2024.

- ^ a b c d "The Union Avoidance Industry in the United States", British Journal of Industrial Relations, John Logan, Blackwell Publishing Ltd, December 2006, pages 651–675.

- ^ Confessions of a Union Buster, Martin Jay Levitt, 1993, page 33.

- ^ From Blackjacks To Briefcases — A History of Commercialized Strikebreaking and Unionbusting in the United States, Robert Michael Smith, 2003, page 97.

- ^ Confessions of a Union Buster, Martin Jay Levitt, 1993, page 33-34.

- ^ "Investigation of improper activities in the labor or management field. Hearings before the Select Committee on Improper Activities in the Labor or Management Field". 1957.

- ^ a b Victor Riesel (May 28, 1957). "Nate Shefferman To Face Senate Probers' Questions". Inside Labor. Beaver Valley Times.

- ^ From Blackjacks To Briefcases — A History of Commercialized Strikebreaking and Unionbusting in the United States, Robert Michael Smith, 2003, pages 98-99.

- ^ Confessions of a Union Buster, Martin Jay Levitt, 1993, page 35.

- ^ Center for Labor Education & Research, University of Hawaii - West Oahu: Honolulu Record Digitization Project Honolulu Record, Volume 10 No. 35, Thursday, March 27, 1958 p. 2,

- ^ From Blackjacks To Briefcases — A History of Commercialized Strikebreaking and Unionbusting in the United States, Robert Michael Smith, 2003, pages 98–100.

- ^ Confessions of a Union Buster, Martin Jay Levitt, 1993, pages 37–38.

- ^ a b From Blackjacks To Briefcases: A History of Commercialized Strikebreaking and Unionbusting in the United States, Robert Michael Smith, 2003, page 102.

- ^ Why America Needs Unions, BusinessWeek

- ^ From Blackjacks To Briefcases — A History of Commercialized Strikebreaking and Unionbusting in the United States, Robert Michael Smith, 2003, page xvii.

- ^ CNN, 2 Sept. 2017, "The Corporate War against Unions" citing Logan, John, "The Union Avoidance Industry in the United States", British Journal of Industrial Relations, Vol. 44, No. 4, pp. 651-675, December 2006

- ^ From Blackjacks To Briefcases — A History of Commercialized Strikebreaking and Unionbusting in the United States, Robert Michael Smith, 2003, page 105.

- ^ From Blackjacks To Briefcases — A History of Commercialized Strikebreaking and Unionbusting in the United States, Robert Michael Smith, 2003, page 108-114.

- ^ "Unhappy Again". Time. October 6, 1986. Archived from the original on September 3, 2007. Retrieved August 15, 2007.

- ^ "Patco Decertification Vote Is Switched From 2–1 to 3–0". The New York Times. November 5, 1981. p. 21. Archived from the original on April 11, 2010. Retrieved April 22, 2024.

- ^ Early, Steve (July 31, 2006). "An old lesson still holds for unions". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on May 12, 2008. Retrieved August 15, 2007.

- ^ From Blackjacks To Briefcases — A History of Commercialized Strikebreaking and Unionbusting in the United States, Robert Michael Smith, 2003, page 119.

- ^ Tasini, Jonathan (September 2, 2017). "The corporate war against unions". CNN. Archived from the original on September 2, 2017. Retrieved March 16, 2024.

- ^ Grabell, Michael (May 1, 2017). "Exploitation and Abuse at the Chicken Plant". The New Yorker. ISSN 0028-792X. Archived from the original on May 1, 2017. Retrieved March 16, 2024.

- ^ Winner-Take-All Politics: How Washington Made the Rich Richer--and Turned Its Back on the Middle Class, Jacob S. Hacker and Paul Pierson, Figure 5, p.61. Sources: David Card, Thomas Lemieux, and W. Craig Riddell, `Unions and Wage Inequality`, Journal of Labor Research 25. n.4 (2004): 519-59; Sylvia Allegreto, Lawrence Mishel, and Jard Bernstein, The State of Working America Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2008

- ^ RICHARD B. FREEMAN, America Works: Critical Thoughts on the Exceptional U.S. Labor Market, p.82-84

- ^ Winner-Take-All Politics, Hacker and Pierson, p.58-60

- ^ Jelle Visser, Union membership statistics in 24 countries, Monthly Labor Review, Jan. 2006, p.38-49.

- ^ (Winner-Take-All Politics, Hacker and Pierson, p.60)

- ^ Bacon, David. "The New Face of Unionbusting". dbacon.igc.org. Archived from the original on May 17, 2003. Retrieved March 16, 2024.

- ^ a b Lafer, Gordon; Loustaunau, Lola (July 23, 2020). "Fear at work: An inside account of how employers threaten, intimidate, and harass workers to stop them from exercising their right to collective bargaining". Economic Policy Institute. Archived from the original on May 14, 2024. Retrieved June 2, 2024.

- ^ McNicholas, Celine; Poydock, Margaret; Sanders, Samantha; Zipperer, Ben (March 29, 2023). "Employers spend more than $400 million per year on 'union-avoidance' consultants to bolster their union-busting efforts". Economic Policy Institute. Archived from the original on November 14, 2024. Retrieved November 23, 2024.

- ^ Hsu, Andrea (July 31, 2024). "Illinois bans companies from forcing workers to listen to their anti-union talk". NPR. Archived from the original on July 31, 2024. Retrieved November 23, 2024.

- ^ a b Marr, Chris (March 1, 2024). "States Advance New 'Captive Audience' Bans Amid Court Challenges". Bloomberg Law. Archived from the original on September 27, 2024. Retrieved November 23, 2024.

- ^ Office of Public Affairs (November 13, 2024). "Board Rules Captive-Audience Meetings Unlawful". National Labor Relations Board. Retrieved November 21, 2024.

- ^ McNees Blog (November 20, 2024). "NLRB Prohibits Captive Audience Meetings". JDSupra. Retrieved November 21, 2024.

- ^ Ellis, Avery (September 26, 2018). "Amazon's Aggressive Anti-Union Tactics Revealed in Leaked 45-Minute Video". Gizmodo. Archived from the original on April 27, 2024. Retrieved May 8, 2024.

- ^ a b Sainato, Michael (February 10, 2022). "Target directing store managers to prevent workers from unionizing". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on April 14, 2024. Retrieved May 8, 2024.

- ^ a b Greenhouse, Steven (February 26, 2023). "'Old-school union busting': how US corporations are quashing the new wave of organizing". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on February 26, 2023. Retrieved March 16, 2024.

- ^ a b McNicholas, Celine; Poydock, Margaret; Wolfe, Julia; Zipperer, Ben; Lafer, Gordon; Loustaunau, Lola (December 11, 2019). "Unlawful: U.S. employers are charged with violating federal law in 41.5% of all union election campaigns". Economic Policy Institute. Archived from the original on May 27, 2024. Retrieved June 2, 2024.

- ^ a b Streitfeld, David (March 16, 2021). "How Amazon Crushes Unions". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 17, 2024. Retrieved May 21, 2024.

- ^ Sainato, Michael (May 21, 2024). "'You feel like you're in prison': workers claim Amazon's surveillance violates labor law". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on May 21, 2024. Retrieved May 21, 2024.

- ^ Meadows, Jonah (July 3, 2024). "Amazon Drivers Strike Over Labor Violations At Skokie Station". Skokie, IL Patch. Patch Media. Archived from the original on July 3, 2024. Retrieved July 10, 2024.

- ^ Chan, J. Clara (August 13, 2019). "Barstool Sports Founder Dave Portnoy Threatens to Fire Employees Who Try to Unionize". TheWrap. Archived from the original on March 2, 2024. Retrieved August 14, 2024.

- ^ a b Porter, Jon (January 22, 2020). "Barstool Sports founder forced to delete tweet threatening to fire union supporters 'on the spot'". The Verge. Archived from the original on April 17, 2023. Retrieved August 14, 2024.

- ^ McNamara, Audrey (January 22, 2020). "Barstool Sports co-founder David Portnoy settles over anti-union tweets". CBS News. Archived from the original on April 11, 2024. Retrieved August 14, 2024.

- ^ Valentine, Rebekah (September 14, 2021). "Activision Blizzard Employees File NLRB Suit Accusing Company of Union Busting, Intimidation". IGN. Archived from the original on January 18, 2024. Retrieved June 14, 2024.

- ^ Klein, Charlotte (January 26, 2022). ""Juneteenth Is a Pretty Aggressive Holiday to Take Hostages With": 'NYT' Union Views New Holiday Schedule as Latest Union-Busting Bid". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on May 31, 2023. Retrieved June 1, 2024.

- ^ Sainato, Michael (February 1, 2022). "Leaked messages reveal New York Times' aggressive anti-union strategy". The Guardian. Archived from the original on May 8, 2024. Retrieved June 1, 2024.

- ^ NYTimesGuild [@NYTimesGuild] (January 26, 2022). "Yesterday we filed an Unfair Labor Practice charge over the Times' use of holiday pay as a union-busting tactic. Today @nytimes ramped up these tactics by announcing a better bereavement leave policy for NON-UNION employees only, the week @nytguildtech ballots have gone out" (Tweet). Retrieved June 1, 2024 – via Twitter.

- ^ Clinkscales, Jason (July 22, 2023). "Union filing grievance over New York Times shuttering of sports desk". Yardbarker. Archived from the original on June 1, 2024. Retrieved June 1, 2024.

- ^ Jones, Tom; Fu, Angela (July 21, 2023). "New York Times hit with grievance, grim layoff news at Hearst magazines, and other media links for your weekend". Poynter. Archived from the original on January 27, 2024. Retrieved June 1, 2024.

- ^ Delkic, Melina (August 15, 2022). "Trader Joe's Abruptly Closes Its Only New York Wine Store". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 15, 2022. Retrieved March 16, 2024.

- ^ Sainato, Michael (September 4, 2022). "Trader Joe's broke labor laws in effort to stop stores unionizing, workers say". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on September 4, 2022. Retrieved March 16, 2024.

- ^ Hawkins, Andrew J. (December 19, 2022). "Tesla accused of illegally firing two employees after they criticized Elon Musk". The Verge. Archived from the original on April 13, 2024. Retrieved June 1, 2024.

- ^ Ewing, Jack; Scheiber, Noam (February 16, 2023). "Tesla Fired Buffalo Workers Seeking to Organize, Union Says". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 16, 2023. Retrieved March 16, 2024.

- ^ Palmer, Annie; Kolodny, Lora (February 16, 2023). "Tesla denies Autopilot workers' allegations of union-busting, retaliatory firings". CNBC. Archived from the original on April 10, 2024. Retrieved June 1, 2024.

- ^ Wiessner, Daniel (November 27, 2023). "Tesla beats US claim that it fired factory workers amid union campaign". Reuters. Archived from the original on November 30, 2023. Retrieved June 1, 2024.

- ^ Stein, Michael Isaac (August 22, 2023). "How Lowe's fought back unionization in New Orleans". WWNO. Archived from the original on February 14, 2024. Retrieved May 9, 2024.

- ^ Sainato, Michael (August 14, 2024). "SkyWest Airlines facing federal lawsuit over alleged 'fake company union'". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on August 22, 2024. Retrieved September 5, 2024.

- ^ "Flight Attendant Union Sues SkyWest for Illegal Termination and Fake Company Union". Association of Flight Attendants-CWA. October 11, 2023. Archived from the original on August 14, 2024. Retrieved September 5, 2024.

- ^ Wiessner, Daniel (November 15, 2023). "REI accused of widespread labor law violations at unionized US stores". Reuters. Archived from the original on November 15, 2023. Retrieved April 23, 2024.

- ^ Thornton, William (March 26, 2024). "Mercedes-Benz retaliated against Alabama workers organizing for UAW, union says". AL.com. Advance Local. Archived from the original on March 26, 2024. Retrieved April 11, 2024.

- ^ Stephenson, Jemma (May 24, 2024). "UAW files objections to Mercedes-Benz union vote". Alabama Reflector. Archived from the original on May 24, 2024. Retrieved May 25, 2024.

- ^ Chandler, Kim (May 24, 2024). "UAW files objection to Mercedes vote, accuses company of intimidating workers". AP News. Archived from the original on May 24, 2024. Retrieved May 25, 2024.

- ^ Ekere, Janie (July 1, 2024). "Sierra Club Turmoil Triggers Strike". The American Prospect. Archived from the original on July 1, 2024. Retrieved July 2, 2024.

- ^ Plummer, Dylan (May 7, 2024). "BREAKING: Sierra Club Staff Union Files New Charges Against Proposed Layoffs Targeting Half of Union's Bargaining Team". Progressive Workers Union. Archived from the original on May 7, 2024. Retrieved July 2, 2024.

- ^ Levine, Gloria (June 12, 2024). "Microsoft QA Contractors Say They Were Fired for Trying to Unionize". 80.lv. Archived from the original on June 13, 2024. Retrieved June 14, 2024.

- ^ Reuben, Nic (June 12, 2024). "Activision QA supplier Lionbridge accused of retaliatory layoffs in "union busting" move". Rock Paper Shotgun. Archived from the original on June 12, 2024. Retrieved June 14, 2024.

- ^ Sainato, Michael (June 24, 2024). "DC coffee chain lists CEOs and Uber lobbyist as baristas to halt union drive". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on June 24, 2024. Retrieved June 25, 2024.

- ^ Myong, Elizabeth (August 10, 2024). "Dallas Black Dance Theatre has fired its entire company of dancers, according to union". KERA News. Archived from the original on August 13, 2024. Retrieved August 14, 2024.

- ^ Myong, Elizabeth (August 12, 2024). "Dallas Black Dance Theatre says dancers were fired over video not union efforts". Dallas Morning News. MSN. Archived from the original on August 14, 2024. Retrieved August 14, 2024.

- ^ Sainato, Michael (August 13, 2024). "UAW files charge against Donald Trump and Elon Musk over strike threat". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on August 13, 2024. Retrieved August 13, 2024.