I Have a Dream

| External audio | |

|---|---|

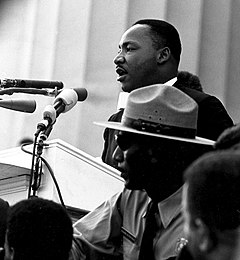

"I Have a Dream" is a public speech that was delivered by American civil rights activist and Baptist minister[2] Martin Luther King Jr. during the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom on August 28, 1963. In the speech, King called for civil and economic rights and an end to racism in the United States. Delivered to over 250,000 civil rights supporters from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., the speech was one of the most famous moments of the civil rights movement and among the most iconic speeches in American history.[3][4]

Beginning with a reference to the Emancipation Proclamation, which declared millions of slaves free in 1863,[5] King said: "one hundred years later, the Negro still is not free".[6] Toward the end of the speech, King departed from his prepared text for an improvised peroration on the theme "I have a dream". In the church spirit, Mahalia Jackson lent her support from her seat behind him, shouting, "Tell 'em about the dream, Martin!" just before he began his most famous segment of the speech. Taylor Branch writes that King later said he grasped at the "first run of oratory" that came to him, not knowing if Jackson's words ever reached him.[7] Jon Meacham writes that, "With a single phrase, King joined Jefferson and Lincoln in the ranks of men who've shaped modern America".[8] The speech was ranked the top American speech of the 20th century in a 1999 poll of scholars of public address.[9] The speech has also been described as having "a strong claim to be the greatest in the English language of all time".[10]

Background

The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom was partly intended to demonstrate mass support for the civil rights legislation proposed by President John F. Kennedy in June. Martin Luther King and other leaders, therefore, agreed to keep their speeches calm, also, to avoid provoking the civil disobedience which had become the hallmark of the Civil Rights Movement. King originally designed his speech as a homage to Abraham Lincoln's Gettysburg Address, timed to correspond with the centennial of the Emancipation Proclamation.[11]

Speech title and the writing process

King had been preaching about dreams since 1960, when he gave a speech to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) called "The Negro and the American Dream". This speech discusses the gap between the American dream and reality, saying that overt white supremacists have violated the dream, and that "our federal government has also scarred the dream through its apathy and hypocrisy, its betrayal of the cause of justice". King suggests that "It may well be that the Negro is God's instrument to save the soul of America."[12][13] In 1961, he spoke of the Civil Rights Movement and student activists' "dream" of equality—"the American Dream ... a dream as yet unfulfilled"—in several national speeches and statements and took "the dream" as the centerpiece for these speeches.[14]

On November 27, 1962, King gave a speech at Booker T. Washington High School in Rocky Mount, North Carolina. That speech was longer than the version which he would eventually deliver from the Lincoln Memorial. And while parts of the text had been moved around, large portions were identical, including the "I have a dream" refrain.[15][16] After being rediscovered in 2015,[17] the restored and digitized recording of the 1962 speech was presented to the public by the English department of North Carolina State University.[15]

King had also delivered a speech with the "I have a dream" refrain in Detroit, in June 1963, before 25,000 people in Detroit's Cobo Hall immediately after the 125,000-strong Great Walk to Freedom on June 23, 1963.[18][19][20] Reuther had given King an office at Solidarity House, the United Auto Workers headquarters in Detroit, where King worked on his "I Have a Dream" speech in anticipation of the March on Washington.[21] Mahalia Jackson, who sang "How I Got Over",[22] just before the speech in Washington, knew about King's Detroit speech.[23] After the Washington, D.C. March, a recording of King's Cobo Hall speech was released by Detroit's Gordy Records as an LP entitled The Great March To Freedom.[24]

The March on Washington Speech, known as "I Have a Dream Speech", has been shown to have had several versions, written at several different times.[25] It has no single version draft, but is an amalgamation of several drafts, and was originally called "Normalcy, Never Again". Little of this, and another "Normalcy Speech", ended up in the final draft. A draft of "Normalcy, Never Again" is housed in the Morehouse College Martin Luther King Jr. Collection of the Robert W. Woodruff Library, Atlanta University Center and Morehouse College.[26] The focus on "I have a dream" comes through the speech's delivery. Toward the end of its delivery, King departed from his prepared remarks and started "preaching" improvisationally, punctuating his points with "I have a dream." In the church spirit, Mahalia Jackson lent her support from her seat behind him, shouting, "Tell 'em about the dream, Martin!" just before he began his most famous segment of the speech. Taylor Branch writes that King later said he grasped at the "first run of oratory" that came to him, not knowing if Jackson's words ever reached him.[7]

The speech was drafted with the assistance of Stanley Levison and Clarence Benjamin Jones[27] in Riverdale, New York City. Jones has said that "the logistical preparations for the march were so burdensome that the speech was not a priority for us" and that, "on the evening of Tuesday, Aug. 27, (12 hours before the march) Martin still didn't know what he was going to say".[28]

Speech

I still have a dream, a dream deeply rooted in the American dream – one day this nation will rise up and live up to its creed, "We hold these truths to be self evident: that all men are created equal." I have a dream ...

—Martin Luther King Jr. (1963)[29]

Widely hailed as a masterpiece of rhetoric, King's speech invokes pivotal documents in American history, including the Declaration of Independence, the Emancipation Proclamation, and the United States Constitution. Early in his speech, King alludes to Abraham Lincoln's Gettysburg Address by saying: "Five score years ago ...". In reference to the abolition of slavery articulated in the Emancipation Proclamation, King says: "It came as a joyous daybreak to end the long night of their captivity." Anaphora (i.e., the repetition of a phrase at the beginning of sentences) is employed throughout the speech. Early in his speech, King urges his audience to seize the moment; "Now is the time" is repeated three times in the sixth paragraph. The most widely cited example of anaphora is found in the often quoted phrase "I have a dream", which is repeated eight times as King paints a picture of an integrated and unified America for his audience. Other occasions include "One hundred years later", "We can never be satisfied", "With this faith", "Let freedom ring", and "free at last". King was the sixteenth out of eighteen people to speak that day, according to the official program.[30]

Among the most quoted lines of the speech are "I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character. I have a dream today!"[31]

According to US representative John Lewis, who also spoke that day as the president of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, "Dr. King had the power, the ability, and the capacity to transform those steps on the Lincoln Memorial into a monumental area that will forever be recognized. By speaking the way he did, he educated, he inspired, he informed not just the people there, but people throughout America and unborn generations."[32]

The ideas in the speech reflect King's social experiences of ethnocentric abuse, mistreatment, and exploitation of black people.[33] The speech draws upon appeals to America's myths as a nation founded to provide freedom and justice to all people, and then reinforces and transcends those secular mythologies by placing them within a spiritual context by arguing that racial justice is also in accord with God's will. Thus, the rhetoric of the speech provides redemption to America for its racial sins.[34] King describes the promises made by America as a "promissory note" on which America has defaulted. He says that "America has given the Negro people a bad check", but that "we've come to cash this check" by marching in Washington, D.C.

Similarities and allusions

King's speech used words and ideas from his own speeches and other texts. For years, he had spoken about dreams, quoted from Samuel Francis Smith's popular patriotic hymn "America (My Country, 'Tis of Thee)", and referred extensively to the Bible. The idea of constitutional rights as an "unfulfilled promise" was suggested by Clarence Jones.[12]

The final passage from King's speech closely resembles Archibald Carey Jr.'s address to the 1952 Republican National Convention: both speeches end with a recitation of the first verse of "America", and the speeches share the name of one of several mountains from which both exhort "let freedom ring".[12][35]

King is said to have used portions of SNCC activist Prathia Hall's speech at the site of Mount Olive Baptist, a burned-down African-American church in Terrell County, Georgia, in September 1962, in which she used the repeated phrase "I have a dream".[36] The church burned down after it was used for voter registration meetings.[37]

The speech in the cadences of a sermon is infused with allusions to biblical verses, including Isaiah 40:4–5 ("I have a dream that every valley shall be exalted ..."[38]) and Amos 5:24 ("But let justice roll down like water ..."[39]).[2] The end of the speech alludes to Galatians 3:28: "There is no longer Jew or Greek, there is no longer slave or free, there is no longer male and female; for all of you are one in Christ Jesus".[40] He also alludes to the opening lines of Shakespeare's Richard III ("Now is the winter of our discontent / Made glorious summer ...") when he remarks that "this sweltering summer of the Negro's legitimate discontent will not pass until there is an invigorating autumn ..."[41]

Rhetoric

The "I Have a Dream" speech can be dissected by using three rhetorical lenses: voice merging, prophetic voice, and dynamic spectacle.[42] Voice merging is the combining of one's own voice with religious predecessors. Prophetic voice is using rhetoric to speak for a population. A dynamic spectacle has origins from the Aristotelian definition as "a weak hybrid form of drama, a theatrical concoction that relied upon external factors (shock, sensation, and passionate release) such as televised rituals of conflict and social control."[43]

The rhetoric of King's speech can be compared to the rhetoric of Old Testament prophets. During his speech, King speaks with urgency and crisis, giving him a prophetic voice. The prophetic voice must "restore a sense of duty and virtue amidst the decay of venality."[44] An evident example is when King declares that "now is the time to make justice a reality for all of God's children."

Voice merging is a technique often used by African-American preachers. It combines the voices of previous preachers, excerpts from scriptures, and the speaker's own thoughts to create a unique voice. King uses voice merging in his peroration when he references the secular hymn "America".[citation needed]

A dynamic spectacle is dependent on the situation in which it is used. King's speech can be classified as a dynamic spectacle, given "the context of drama and tension in which it was situated" (during the Civil Rights Movement and the March on Washington).[45]

Why King's speech was powerful is debated. Executive speechwriter Anthony Trendl writes, "The right man delivered the right words to the right people in the right place at the right time."[46]

Responses

You could feel "the passion of the people flowing up to him," James Baldwin, a skeptic of that day’s March on Washington, later wrote, and in that moment, "it almost seemed that we stood on a height, and could see our inheritance; perhaps we could make the kingdom real."

M. Kakutani, The New York Times[2]

The speech was lauded in the days after the event and was widely considered the high point of the March by contemporary observers.[47] James Reston, writing for The New York Times, said that "Dr. King touched all the themes of the day, only better than anybody else. He was full of the symbolism of Lincoln and Gandhi, and the cadences of the Bible. He was both militant and sad, and he sent the crowd away feeling that the long journey had been worthwhile."[12] Reston also noted that the event "was better covered by television and the press than any event here since President Kennedy's inauguration", and opined that "it will be a long time before [Washington] forgets the melodious and melancholy voice of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. crying out his dreams to the multitude."[48]

An article in The Boston Globe by Mary McGrory reported that King's speech "caught the mood" and "moved the crowd" of the day "as no other" speaker in the event.[49] Marquis Childs of The Washington Post wrote that King's speech "rose above mere oratory".[50] An article in the Los Angeles Times commented that the "matchless eloquence" displayed by King—"a supreme orator" of "a type so rare as almost to be forgotten in our age"—put to shame the advocates of segregation by inspiring the "conscience of America" with the justice of the civil-rights cause.[51]

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), which viewed King and his allies for racial justice as subversive, also noticed the speech. This provoked the organization to expand their COINTELPRO operation against the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), and to target King specifically as a major enemy of the United States.[52] Two days after King delivered "I Have a Dream", Agent William C. Sullivan, the head of COINTELPRO, wrote a memo about King's growing influence:

Personally, I believe in the light of King's powerful demagogic speech yesterday he stands head and shoulders above all other Negro leaders put together when it comes to influencing great masses of Negroes. We must mark him now, if we have not done so before, as the most dangerous Negro of the future in this Nation from the standpoint of communism, the Negro and national security.[53]

The speech was a success for the Kennedy administration and for the liberal civil rights coalition that had planned it. It was considered a "triumph of managed protest", and not one arrest relating to the demonstration occurred. Kennedy had watched King's speech on television and been very impressed. Afterward, March leaders accepted an invitation to the White House to meet with President Kennedy. Kennedy felt the March bolstered the chances for his civil rights bill.[54]

Some Black leaders later criticized the speech (along with the rest of the march) as too compromising. Malcolm X later wrote in his autobiography: "Who ever heard of angry revolutionaries swinging their bare feet together with their oppressor in lily pad pools, with gospels and guitars and 'I have a dream' speeches?"[11]

Legacy

The March on Washington put pressure on the Kennedy administration to advance its civil rights legislation in Congress.[55] The diaries of Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr., published posthumously in 2007, suggest that President Kennedy was concerned that if the march failed to attract large numbers of demonstrators, it might undermine his civil rights efforts.[citation needed]

In the wake of the speech and march, King was named Man of the Year by TIME magazine for 1963, and in 1964 he was the youngest man ever awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.[56] The full speech did not appear in writing until August 1983, some 15 years after King's death, when a transcript was published in The Washington Post.[6]

In 1990, the Australian alternative comedy rock band Doug Anthony All Stars released an album called Icon. One song from Icon, "Shang-a-lang", sampled the end of the speech.[citation needed]

In 1992, the band Moodswings, incorporated excerpts from Martin Luther King Jr.'s "I Have a Dream" speech in their song "Spiritual High, Part III" on the album Moodfood.[57][58]

Also in 1992, rock band Extreme incorporated parts of the Detroit speech into their song "Peacemaker Die" on the album III Sides to Every Story.[59]

In 2002, the Library of Congress honored the speech by adding it to the United States National Recording Registry.[60] In 2003, the National Park Service dedicated an inscribed marble pedestal to commemorate the location of King's speech at the Lincoln Memorial.[61]

Near the Potomac Basin in Washington, D.C., the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial was dedicated in 2011. The centerpiece for the memorial is based on a line from King's "I Have A Dream" speech: "Out of a mountain of despair, a stone of hope."[62] A 30-foot (9.1 m)-high relief sculpture of King named the Stone of Hope stands past two other large pieces of granite that symbolize the "mountain of despair" split in half.[62]

On August 26, 2013, UK's BBC Radio 4 broadcast "God's Trombone", in which Gary Younge looked behind the scenes of the speech and explored "what made it both timely and timeless".[63]

On August 28, 2013, thousands gathered on the mall in Washington, D.C. where King made his historic speech to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the occasion. In attendance were former US Presidents Bill Clinton and Jimmy Carter, and incumbent President Barack Obama, who addressed the crowd and spoke on the significance of the event. Many of King's family were in attendance.[64]

On October 11, 2015, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution published an exclusive report about Stone Mountain officials considering the installation of a new "Freedom Bell" honoring King and citing the speech's reference to the mountain "Let freedom ring from Stone Mountain of Georgia."[65] Design details and a timeline for its installation remain to be determined. The article mentioned the inspiration for the proposed monument came from a bell-ringing ceremony held in 2013 in celebration of the 50th anniversary of King's speech.[citation needed]

On April 20, 2016, Treasury Secretary Jacob Lew announced that the US $5 bill, which has featured the Lincoln Memorial on its back, would undergo a redesign prior to 2020. Lew said that a portrait of Lincoln would remain on the front of the bill, but the back would be redesigned to depict various historical events that have occurred at the memorial, including an image from King's speech.[66]

Ava DuVernay was commissioned by the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture to create a film that debuted at the museum's opening on September 24, 2016. This film, August 28: A Day in the Life of a People (2016), tells of six significant events in African-American history that happened on the same date, August 28. Events depicted include (among others) the speech.[67]

In October 2016, Science Friday in a segment on its crowd sourced update to the Voyager Golden Record included the speech.[68]

In 2017, the statue of Martin Luther King Jr. on the grounds of the Georgia State Capitol was unveiled on the 54th anniversary of the speech.[69]

Time partnered with Epic Games to create an interactive exhibit dedicated to the speech within Epic's game Fortnite Creative on the 58th anniversary of the speech.[70]

Copyright dispute

Because King's speech was broadcast to a large radio and television audience, there was controversy about its copyright status. If the performance of the speech constituted "general publication", it would have entered the public domain due to King's failure to register the speech with the Register of Copyrights. But if the performance constituted only "limited publication", King retained common law copyright. This led to a lawsuit, Estate of Martin Luther King, Jr., Inc. v. CBS, Inc., which established that the King estate did hold copyright over the speech and had standing to sue; the parties then settled. Unlicensed use of the speech or a part of it can still be lawful in some circumstances, especially in jurisdictions under doctrines such as fair use or fair dealing. Under the applicable copyright laws, the speech will remain under copyright in the United States until 70 years after King's death, through 2038.[71][72][73][74]

Original copy of the speech

As King waved goodbye to the audience, George Raveling, volunteering as a security guard at the event, asked King if he could have the original typewritten manuscript of the speech.[75] Raveling, a star college basketball player for the Villanova Wildcats, was on the podium with King at that moment.[76] King gave it to him. Raveling kept custody of the original copy, for which he has been offered $3 million, but he has said he does not intend to sell it.[77][78] In 2021, he gave it to Villanova University. It is intended to be used in a "long-term 'on loan' arrangement."[79]

Chart performance

In the wake of King's death, the speech was issued as a single under Gordy Records and managed to crack onto the Billboard Hot 100, peaking at number 88.[80]

References

- ^ "Special Collections, March on Washington, Part 17". Open Vault. at WGBH. August 28, 1963. Archived from the original on December 26, 2018. Retrieved September 15, 2016.

- ^ a b c Kakutani, Michiko (August 28, 2013). "The Lasting Power of Dr. King's Dream Speech". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 8, 2021. Retrieved August 28, 2021.

- ^ Hansen, D. D. (2003). The Dream: Martin Luther King Jr. and the Speech that Inspired a Nation. New York: Harper Collins. p. 177. OCLC 473993560.

- ^ Tikkanen, Amy (August 29, 2017). "I Have a Dream". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on October 20, 2018. Retrieved May 7, 2019.

- ^ Echols, James (2004), I Have a Dream: Martin Luther King Jr. and the Future of Multicultural America.

- ^ a b Alexandra Alvarez, "Martin Luther King's 'I Have a Dream': The Speech Event as Metaphor", Journal of Black Studies 18(3); doi:10.1177/002193478801800306.

- ^ a b Branch, Taylor, Parting the Waters: America in the King Years 1954–63, pgs. 2761–2763, Simon & Schuster (1998). ISBN 978-1-4165-5868-2

- ^ Meacham, Jon (August 26, 2013). "One Man". Time. p. 26.

- ^ Lucas, Stephen; Medhurst, Martin (December 15, 1999). "I Have a Dream Speech Leads Top 100 Speeches of the Century". University of Wisconsin–Madison. Archived from the original on February 10, 2016. Retrieved July 18, 2006.

- ^ O'Grady, Sean (April 3, 2018). "Martin Luther King's 'I Have a Dream' speech is the greatest oration of all time". The Independent. Archived from the original on January 28, 2021. Retrieved December 19, 2020.

- ^ a b X, Malcolm; Haley, Alex (1973). Autobiography of Malcolm X. New York: Ballantine Books. p. 281.

- ^ a b c d "I Have a Dream". The Martin Luther King Jr. Research and Education Institute. May 8, 2017. Archived from the original on December 4, 2019. Retrieved December 4, 2019.

- ^ Martin Luther King Jr., "The Negro and the American Dream Archived December 18, 2014, at the Stanford Web Archive", speech delivered to the NAACP in Charlotte, NC, September 25, 1960.

- ^ Cullen, Jim (2003). The American Dream: A Short History of an Idea that Shaped a Nation. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 126. ISBN 0195158210.

- ^ a b Stringer, Sam; Brumfield, Ben (August 12, 2015). "New recording: King's first 'I have a dream' speech found at high school". CNN. Archived from the original on August 13, 2015. Retrieved August 13, 2015.

- ^ Crook, Samantha; Bryant, Christian. "How Langston Hughes Led to a 'Dream' MLK Discovery". WKBW-TV. Archived from the original on July 23, 2017. Retrieved August 13, 2015.

- ^ Waggoner, Martha (August 11, 2015). "Recording of MLK's 1st 'I Have a Dream' speech found". DetroitNews.com. Associated Press. Archived from the original on September 12, 2015. Retrieved August 13, 2015.

- ^ Boyle, Kevin (May 1, 2007), "Detroit's Walk To Freedom", Michigan History Magazine, archived from the original on May 18, 2012, retrieved February 15, 2012

- ^ Garrett, Bob, Martin Luther King Jr. and the Detroit Freedom Walk, Michigan Department of Natural Resources – Michigan Library and Historical – Center Michigan Historical Center, archived from the original on March 1, 2014, retrieved February 15, 2012

- ^ O'Brien, Soledad (August 22, 2003). "Interview With Martin Luther King III". CNN. Archived from the original on June 3, 2018. Retrieved January 15, 2007.

- ^ Kaufman, Dan (September 26, 2019). "On the Picket Lines of the General Motors Strike". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on June 3, 2020. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- ^ Kot, Greg (October 21, 2014). "How Mahalia Jackson defined the 'I Have a Dream' speech". BBC. Archived from the original on August 30, 2018. Retrieved August 28, 2018.

- ^ Norris, Michele (August 28, 2013). "For King's Adviser, Fulfilling The Dream 'Cannot Wait'". NPR. Archived from the original on August 30, 2018. Retrieved August 29, 2018.

- ^ Ward, Brian (1998), Recording the Dream, vol. 48, History Today, archived from the original on February 15, 2012, retrieved February 15, 2012

- ^ Hansen 2003, p. 70. The original name of the speech was "Cashing a Cancelled Check", but the aspired ad lib of the dream from preacher's anointing brought forth a new entitlement, "I Have A Dream".

- ^ Morehouse College Martin Luther King Jr. Collection, 2009 "Notable Items Archived December 15, 2013, at the Wayback Machine" Retrieved December 4, 2013

- ^ "Jones, Clarence Benjamin (1931– )". Martin Luther King Jr. and the Global Freedom Struggle (Stanford University). Archived from the original on June 6, 2008. Retrieved February 28, 2011.

- ^ Jones, Clarence B. (January 16, 2011). "On Martin Luther King Day, remembering the first draft of 'I Have a Dream'". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved February 28, 2011.

- ^ Edwards, Willard. (August 29, 1963). 200,000 Roar Plea for Negro Opportunity in Rights March on Washington. Chicago Tribune, p. 5.

- ^ "Document for August 28th: Official Program for the March on Washington". Archives.gov. August 15, 2016. Archived from the original on July 21, 2017. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- ^ Excel HSC Standard English, p. 108, Lloyd Cameron, Barry Spurr – 2009

- ^ "A "Dream" Remembered". NewsHour. August 28, 2003. Archived from the original on May 4, 2006. Retrieved July 19, 2006.

- ^ Exploring Religion and Ethics: Religion and Ethics for Senior Secondary Students, p. 192, Trevor Jordan – 2012.

- ^ See David A. Bobbitt, The Rhetoric of Redemption: Kenneth Burke's Redemption Drama and Martin Luther King Jr.'s "I Have a Dream" Speech, Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2004.

- ^ John, Derek (August 28, 2013). "Long lost civil rights speech helped inspire King's dream". WBEZ. Archived from the original on January 1, 2014. Retrieved August 28, 2017.

- ^ Holsaert, Faith et al. Hands on the Freedom Plow: Personal Accounts by Women in SNCC. University of Illinois Press, 2010, p. 180.

- ^ Civil Rights Digital Library Archived February 26, 2014, at the Wayback Machine: Film (2:30).

- ^ "Isaiah 40:4–5". King James Version of the Bible. Archived from the original on November 21, 2011. Retrieved January 13, 2010.

- ^ "Amos 5:24". King James Version of the Bible. Archived from the original on September 27, 2013. Retrieved August 29, 2013.

- ^ Neutel, Karin (May 19, 2020). "Galatians 3:28—Neither Jew nor Greek, Slave nor Free, Male and Female". Biblical Archaeology Society. Archived from the original on August 5, 2020. Retrieved August 22, 2020.

- ^ Alvarez, Alexandra (March 1988), "Martin Luther King's 'I Have a Dream': The Speech Event as Metaphor", Journal of Black Studies, Vol. 18, No. 3 (pp. 337–357), p. 242.

- ^ Vail, Mark (2006). "The 'Integrative' Rhetoric of Martin Luther King Jr.'S 'I Have a Dream' Speech". Rhetoric and Public Affairs. 9 (1): 52. doi:10.1353/rap.2006.0032. JSTOR 41940035. S2CID 143912415.

- ^ Farrell, Thomas B. (1989). "Media Rhetoric as Social Drama: The Winter Olympics of 1984". Critical Studies in Mass Communication. 6 (2): 159–160. doi:10.1080/15295038909366742.

- ^ Darsey, James (1997). The Prophetic Tradition and Radical Rhetoric in America. New York: New York University Press. pp. 10, 19, 47. ISBN 9780814718766.

- ^ Vail 2006, p. 55.

- ^ Trendl, Anthony. "I Have a Dream Analysis". Archived from the original on April 5, 2018. Retrieved April 4, 2018.

- ^ "The News of the Week in Review: March on Washington—Symbol of intensified drive for Negro rights," The New York Times (September 1, 1963). "The high point and climax of the day, it was generally agreed, was the eloquent and moving speech late in the afternoon by the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. ..."

- ^ James Reston, "'I Have a Dream ... ': Peroration by Dr. King sums up a day the capital will remember", The New York Times (August 29, 1963).

- ^ Mary McGrory, "Polite, Happy, Helpful: The Real Hero Was the Crowd", The Boston Globe (August 29, 1963).

- ^ Marquis Childs, "Triumphal March Silences Scoffers", The Washington Post (August 30, 1963).

- ^ Max Freedman, "The Big March in Washington Described as 'Epic of Democracy'", Los Angeles Times (September 9, 1963).

- ^ Tim Weiner, Enemies: A history of the FBI, New York: Random House, 2012, p. 235

- ^ Memo hosted by American Radio Works (American Public Media), "The FBI's War on King Archived August 25, 2012, at the Wayback Machine".

- ^ Reeves, Richard, President Kennedy: Profile of Power,1993, pp. 580–584

- ^ Clayborne Carson Archived January 2, 2010, at the Wayback Machine "King, Obama, and the Great American Dialogue", American Heritage, Spring 2009.

- ^ "Martin Luther King". The Nobel Foundation. 1964. Archived from the original on February 22, 2011. Retrieved April 20, 2007.

- ^ "Moodswings's 'Spiritual High (Part III)' – Discover the Sample Source". WhoSampled. Archived from the original on August 14, 2021. Retrieved January 29, 2021.

- ^ Keller, Douglas D. (January 20, 1993). "Varied Moodswings album provides musing to fuel any emotion". The Tech. 112 (66): 6. Archived from the original on February 3, 2021. Retrieved January 29, 2021.

- ^ "Extreme's 'Peacemaker Die' sample of Martin Luther King, Jr.'s 'I Have a Dream (Detroit)'". WhoSampled. Retrieved July 13, 2024.

- ^ "The National Recording Registry 2002". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on March 15, 2015. Retrieved December 29, 2017.

- ^ "We Shall Overcome, Historic Places of the Civil Rights Movement: Lincoln Memorial". US National Park Service. Archived from the original on January 5, 2007. Retrieved January 15, 2007.

- ^ a b "Tears Fall at the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial". WUSA. June 30, 2011. Archived from the original on September 4, 2011. Retrieved September 10, 2011.

- ^ "God's Trombone: Remembering King's Dream". BBC. August 26, 2013. Archived from the original on August 26, 2013. Retrieved August 26, 2013.

- ^ Miller, Zeke J (August 28, 2013). "In Commemorative MLK Speech, President Obama Recalls His Own 2008 Dream". Time. Archived from the original on September 1, 2013. Retrieved September 1, 2013.

- ^ Galloway, Jim (October 12, 2015). "A monument to MLK will crown Stone Mountain". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Archived from the original on September 28, 2017. Retrieved April 23, 2016.

- ^ Korte, Gregory (April 21, 2016). "Anti-slavery activist Harriet Tubman to replace Jackson on $20 bill". USA Today. Archived from the original on April 23, 2016. Retrieved April 23, 2016.

- ^ Davis, Rachaell (September 22, 2016). "Why Is August 28 So Special To Black People? Ava DuVernay Reveals All in New NMAAHC Film". Essence. Archived from the original on July 16, 2018. Retrieved August 29, 2018.

- ^ "Your Record". Science Friday. October 7, 2016. Archived from the original on October 10, 2016. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ^ Wells, Myrydd (August 28, 2017). "Georgia Capitol's Martin Luther King Jr. statue unveiled on 54th anniversary of "I Have a Dream"". Atlanta. Archived from the original on July 9, 2020. Retrieved July 8, 2020.

- ^ Francis, Bryant (August 26, 2021). "Epic and Time Magazine debut interactive MLK Jr. exhibit in Fortnite". Game Developer. Archived from the original on August 27, 2021. Retrieved August 26, 2021.

- ^ Strauss, Valerie. "'I Have a Dream' speech still private property". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 28, 2013. Retrieved August 28, 2013.

- ^ Williams, Lauren (August 23, 2013). "I Have a Copyright: The Problem With MLK's Speech". Mother Jones. Archived from the original on December 11, 2019. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- ^ Volz, Dustin (August 20, 2013). "The Copyright Battle Behind 'I Have a Dream'". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on August 1, 2020. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- ^ Strauss, Valerie (January 15, 2017). "'I Have a Dream' speech owned by Martin Luther King's family". Toronto Star. Archived from the original on August 28, 2021. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- ^ Suarez, Xavier L. (October 27, 2011). Democracy in America: 2010. AuthorHouse. pp. 10–. ISBN 978-1-4567-6056-4. Archived from the original on July 7, 2014. Retrieved April 28, 2013.

- ^ Karen Price Hossell (December 5, 2005). I Have a Dream. Heinemann-Raintree Library. pp. 34–. ISBN 978-1-4034-6811-6. Archived from the original on July 7, 2014. Retrieved April 28, 2013.

- ^ Weir, Tom (February 27, 2009). "George Raveling owns MLK's 'I have a dream' speech". USA Today. Archived from the original on July 2, 2013. Retrieved April 29, 2013.

- ^ Brinkley, Douglas (August 28, 2003). "Guardian of The Dream". Time. Archived from the original on August 29, 2003. Retrieved August 28, 2013.

- ^ Donohue, Peter M. (August 27, 2021). "A Message from the President | Villanova University". Villanova University. Archived from the original on January 17, 2022. Retrieved January 17, 2022.

- ^ "Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr". Billboard. Retrieved March 24, 2022.

External links

- Full text at the BBC

- Video of "I Have a Dream" speech, from LearnOutLoud.com

- "I Have a Dream" Text and Audio from AmericanRhetoric.com

- "I Have A Dream" speech – Dr. Martin Luther King with music by Doug Katsaros on YouTube

- Deposition concerning recording of the "I Have a Dream" speech

- Lyrics of the traditional spiritual "Free at Last"

- MLK: Before He Won the Nobel; Archived January 18, 2010, at the Wayback Machine – slideshow by Life magazine

- Chiastic outline of Martin Luther King Jr.'s "I Have a Dream" speech

- I Have a Dream Summary (Class 12)

- I Have A Dream Archived February 1, 2021, at the Wayback Machine