Interprovincial migration in Canada

Interprovincial migration in Canada is the movement by people from one Canadian province or territory to another with the intention of settling, permanently or temporarily, in the new province or territory; it is more-or-less stable over time.[1] In fiscal year 2019–20, 278,316 Canadians migrated province, representing 0.729% of the population.[2]

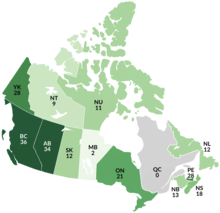

The Interprovincial migration levels of each province can be construed as a way to measure the success of these jurisdiction. The main measurement used is net interprovincial migration, which is simply the difference between residents moving out of a province (out-migration) and the number of residents from other provinces moving into that province (in-migration). Since 1971, the provinces which received the most net cumulative interprovincial migrants (adjusted for population) were Alberta and British Columbia, while the provinces which had the largest net loss of interprovincial migrants (adjusted for population) were Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Quebec, and the Atlantic provinces.[3]

History

[edit]

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, Canadians who left their home province to settle elsewhere usually went to the United States rather than to other Canadian provinces. In fact, from the early years of confederation to the 1930s, Quebec and the Maritimes experienced a period of mass emigration to the United States. From 1860 to 1920, half a million people left the Maritimes,[4] while about 900,000 French Canadians left Quebec between 1840 and 1930 to immigrate to the United States, mainly New England.[5][6]

However, some French Canadians and Maritimers were also drawn to Ontario in the 19th and early 20th centuries, when the development of mining and forestry resources in the northeastern and eastern regions of the province attracted a large workforce. This migration significantly increased the proportion of Francophones in Ontario.[7] The Francophone population of Ontario continues to be concentrated mainly in the northeastern and eastern parts, close to the border with Quebec, although smaller pockets of Francophone settlement exist throughout the province.

After Manitoba joined Confederation in 1870, the new provincial government was controlled by Anglo Canadians. The agreement for the establishment of the province had included guarantees that the Métis would receive grants of land and that their existing unofficial landholdings would be recognized. These guarantees were largely ignored. New anglophone migrants coming from Ontario were instead given most of the land. Facing this discrimination, the Métis moved in large numbers to what would become Saskatchewan and Alberta.[8]

Starting in 1871, the Canadian government entered multiple treaties with indigenous nations to gain their consent to take their lands "for immigration and settlement" in the area of the former Rupert's Land (although many of the treaty terms made to get this consent were subsequently violated by Canada).[9] The Dominion government then passed the Dominion Lands Act in 1872 to encourage the settlement of the Canadian Prairies, and to help prevent the area from being claimed by the United States.[10] The act gave a claimant 160 acres (or 65 hectares) for free, the only cost to the farmer being a $10 administration fee. Any male farmer who was at least 21 years of age and agreed to cultivate at least 40 acres (16 ha) of the land and build a permanent dwelling on it (within three years) qualified.[11] The population of the Canadian prairies grew rapidly in the last decade of the 19th century, and the population of Saskatchewan quintupled from 91,000 in 1901 to 492,000 to 1911.[12] However, the vast majority of these people were immigrants from Europe.[11] Interprovincial migration in Canada was at its highest in the first 20 years of the 20th century, and started to decrease in the 1920s.[13]

Out-emigration from Quebec dramatically spiked in 1977, one year after the Parti Québécois won the 1976 Quebec general elections. It spiked again in 1996, one year after the 1995 Quebec referendum. This second spike was, however, 37.5% the size of the 1977 spike.[3]

Migration from Atlantic Canada to Ontario and the West in search of economic opportunity is longstanding phenomenon. It is depicted in works including Goin' Down the Road (1970), a key piece in Canadian film history. The cod collapse in the early 1990s and the 1992 moratorium on cod fishing led to the migration of workers from Atlantic Canada (particularly Newfoundland and Labrador) to Alberta. Fishing had previously been a major driver of the economies of the Atlantic provinces, and this loss of work proved catastrophic for many families. As a result, beginning in the early 1990s and into the late 2000s, thousands of people from the Atlantic provinces were driven out-of-province to find work elsewhere in the country, especially in the Alberta oil sands during the oil boom of the mid-2000s.[14] This systemic export of labour[15] is explored by author Kate Beaton in her 2022 graphic memoir Ducks, which details her experience working in the Athabasca oil sands.[16][17]

Influences

[edit]A number of factors have been identified by academic research in influencing interprovincial migration.

Demographic factors

[edit]The odds of a Canadian moving from one province to another is inversely related to the home province's population size: the larger the province, the less likely a resident is to move away. Interprovincial migration is negatively related to marriage, and the presence of children for both men and women. Younger people also tend to be more mobile than their older counterparts. Men are more likely to move than women, although men's rates of interprovincial migration are declining slightly while women's are holding steadier or rising slightly.[1]

Interprovincial migration is also more common among residents of smaller cities, towns, and especially rural areas than for residents of larger cities. The largest Canadian population centres (Toronto, Vancouver, Montréal, Calgary and Edmonton) also tend to attract the largest amount of interprovincial migrants, and there is a lot of flow between these cities.[18]

Economic factors

[edit]The economic situation of each province is an important indicator of internal migration within Canada. It is more likely for people to move out of a province with higher unemployment rate. Interprovincial migration is also positively related to the individuals' receipt of unemployment insurance, having no market income, and the receipt of social assistance (especially for men).[1] Canadian provinces also tend to lose more people than they gain when their province is in recession. Alberta, for example, experienced a net loss of people to interprovincial migration from September 2015 to December 2017.[19]

Language

[edit]Language spoken is a strong predictor of interprovincial migration. Francophone Quebeckers are among the groups of people who are the least likely to move across provinces.[20] Francophones in New Brunswick are much less likely to move out of province than their Anglophone counterparts.[13]

The only group less likely to migrate across provinces than Francophone Quebeckers is Francophone immigrants living in Quebec. Inversely, Francophone immigrants living outside Quebec is the group most prone to interprovincial migration, as 9.2% of them move to another province. Over half of Francophones outside Quebec (immigrant and Canada-born) who migrate across provinces choose Quebec as their destination.[20]

Literacy

[edit]Literacy used to be a significant indicator of interprovincial migration in Canada in the late 19th and early 20th century. Anglophone Canadians who could read were more likely to move than their illiterate counterparts. For Francophone Quebeckers, however, this was the opposite, as literate unilingual Francophones were more likely to stay in Quebec than illiterate unilingual Francophones. Literacy had, however, no effect on the likelihood of migration of bilingual Quebeckers.[13]

Provincial level

[edit]

Alberta

[edit]Over the past five decades, Alberta has had the highest net increase from interprovincial migration of any province. However, it typically experiences population decline during economic downturns, as it did during the 1980s.[3] Oil is the main industry driving interprovincial migration to Alberta, as many Canadians move to Alberta to work in the oil fields or spin-off sectors. Interprovincial migration to Alberta rises and drops dependent of the price of oil. There was a dramatic reduction after the 2014 drop in oil prices, however, it dramatically recovered starting in 2021-22 and reached historic highs thereafter.[21][19]

| In-migrants | Out-migrants | Net migration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2011–12 | |||

| 2012–13 | |||

| 2013–14 | |||

| 2014–15 | |||

| 2015–16 | |||

| 2016–17 | |||

| 2017–18 | |||

| 2018–19 | |||

| 2019–20 | |||

| 2020–21 | |||

| 2021–22 | |||

| 2022–23 |

Source: Statistics Canada[2]

British Columbia

[edit]British Columbia has also traditionally been gaining from interprovincial migration. Over the last 50 years, British Columbia had 13 years of negative interprovincial immigration: the lowest in the country. The only time the province significantly lost population to this phenomenon was during the 1990s, when it had a negative interprovincial migration for 5 consecutive years.[3]

| In-migrants | Out-migrants | Net migration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2011–12 | |||

| 2012–13 | |||

| 2013–14 | |||

| 2014–15 | |||

| 2015–16 | |||

| 2016–17 | |||

| 2017–18 | |||

| 2018–19 | |||

| 2019–20 | |||

| 2020–21 | |||

| 2021–22 | |||

| 2022–23 |

Source: Statistics Canada[2]

Manitoba

[edit]Manitoba is one of the provinces most affected by interprovincial migration, having had a negative mobility ratio for 42 out of 46 years from 1971 to 2017. This is the second-worst record for years of negative interprovincial migration, followed only by Quebec.[3]

| In-migrants | Out-migrants | Net migration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2011–12 | |||

| 2012–13 | |||

| 2013–14 | |||

| 2014–15 | |||

| 2015–16 | |||

| 2016–17 | |||

| 2017–18 | |||

| 2018–19 | |||

| 2019–20 | |||

| 2020–21 | |||

| 2021–22 | |||

| 2022–23 |

Source: Statistics Canada[2]

New Brunswick

[edit]New Brunswick has typically experienced less emigration than its size and economic situation would suggest, probably because of the low rate of emigration of its Francophone population.[1] New Brunswick was predicted to continue low or negative population growth in the long term due to interprovincial migration and a low birth rate. However, the rate turned positive starting in 2017, and accelerated upwards afterward.[22]

| In-migrants | Out-migrants | Net migration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2011–12 | |||

| 2012–13 | |||

| 2013–14 | |||

| 2014–15 | |||

| 2015–16 | |||

| 2016–17 | |||

| 2017–18 | |||

| 2018–19 | |||

| 2019–20 | |||

| 2020–21 | |||

| 2021–22 | |||

| 2022–23 |

Source: Statistics Canada[2]

Newfoundland and Labrador

[edit]Since it started being recorded in 1971, Newfoundland and Labrador is the province that has lost the biggest share of its population to interprovincial migration, which was especially high in the 1990s. Out-migration from the province was curtailed in 2008 and net migration stayed positive through 2014, when it again dropped due to bleak finances and rising unemployment (caused by falling oil prices).[3] With the announcement of the 2016 provincial budget, St. John's Telegram columnist Russell Wangersky published the column "Get out if you can", which urged young Newfoundlanders to leave the province to avoid future hardships.[23] In the 2021 Canadian census, Newfoundland and Labrador was the only province which recorded a population decline in the previous five years.

| In-migrants | Out-migrants | Net migration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2011–12 | |||

| 2012–13 | |||

| 2013–14 | |||

| 2014–15 | |||

| 2015–16 | |||

| 2016–17 | |||

| 2017–18 | |||

| 2018–19 | |||

| 2019–20 | |||

| 2020–21 | |||

| 2021–22 | |||

| 2022–23 |

Source: Statistics Canada[2]

Nova Scotia

[edit]From 1971 to 2012, Nova Scotia had a persistent negative trend in net interprovincial migration. Combined with a declining birth rate, this poses a significant demographic challenge for the province, as its population is projected to decline from 948,000 people in 2011 to 926,000 people in 2038. The destination for Nova Scotia migrants was most often Ontario, until the turn of the 21st century when Alberta became a more popular destination; New Brunswick ranks as a distant third. In a dramatic shift, by the late 2010s and especially afterward, Nova Scotia became one of the preferred destinations in Canada with significant in-migration, mainly from Ontario.[24]

| In-migrants | Out-migrants | Net migration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2011–12 | |||

| 2012–13 | |||

| 2013–14 | |||

| 2014–15 | |||

| 2015–16 | |||

| 2016–17 | |||

| 2017–18 | |||

| 2018–19 | |||

| 2019–20 | |||

| 2020–21 | |||

| 2021–22 | |||

| 2022–23 |

Source: Statistics Canada[2]

Ontario

[edit]Ontario's interprovincial migrations have shifted over the years. It was negative in the 1970s, positive in the 1980s, but then negative again in the 1990s. It returned to positive figures around the time of the turn of the millennium, was consistently in the negatives from 2003 to 2015, then returned to the positives through 2018 before returning to negative - a trend that accelerated in the 2020s largely due to high housing prices. Over the period from 1971 to 2015, Ontario was the province that experienced the second-lowest levels of interprovincial in-migration and out-migration, second only to Quebec.[3] Out-migration from Northern Ontario especially of young and working-age adults, either intraprovincially to Southern Ontario or to other provinces especially in the West, has been a public issue since the 1990s.[25]

| In-migrants | Out-migrants | Net migration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2011–12 | |||

| 2012–13 | |||

| 2013–14 | |||

| 2014–15 | |||

| 2015–16 | |||

| 2016–17 | |||

| 2017–18 | |||

| 2018–19 | |||

| 2019–20 | |||

| 2020–21 | |||

| 2021–22 | |||

| 2022–23 |

Source: Statistics Canada[2]

Prince Edward Island

[edit]Since 1971, Prince Edward Island mostly had years of positive interprovincial migration. However, in the 2010s, it turned to the negative for a few years before returning to positive again. This interprovincial migration exceeded all immigration to the province in 2015.[26]

| In-migrants | Out-migrants | Net migration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2011–12 | |||

| 2012–13 | |||

| 2013–14 | |||

| 2014–15 | |||

| 2015–16 | |||

| 2016–17 | |||

| 2017–18 | |||

| 2018–19 | |||

| 2019–20 | |||

| 2020–21 | |||

| 2021–22 | |||

| 2022–23 |

Source: Statistics Canada[2]

Quebec

[edit]Since it began being recorded in 1971 until 2018, each year Quebec has had negative interprovincial migration, and among the provinces it has experienced the largest net loss of people due to the effect.[3] Between 1981 and 2017, Quebec lost about 229,700 people below the age of 45 to interprovincial migration.[27] Per capita, Quebec has lost significantly fewer people than other provinces. This is due to the large population of the province and the very low migration rate of Francophone Quebeckers.[1] However, Quebec receives much fewer than average in-migrants from other provinces.[3]

In Quebec, Allophones are more likely to migrate out of the province than average: between 1996 and 2001, over 19,170 migrated to other provinces; 18,810 of whom migrated to Ontario.[28]

| Mother Tongue / Year | 1971–1976 | 1976–1981 | 1981–1986 | 1986–1991 | 1991–1996 | 1996–2001 | 2001–2006 | 2006–2011 | 2011-2016 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| French | −4,100 | −18,000 | −12,900 | 5,200 | 1,200 | −8,900 | 5,000 | −2,610 | −9,940 | −45,050 |

| English | −52,200 | −106,300 | −41,600 | −22,200 | −24,500 | −29,200 | −8,000 | −5,930 | −11,005 | −300,635 |

| Other | −5,700 | −17,400 | −8,700 | −8,600 | −14,100 | −19,100 | −8,700 | −12,710 | −16,015 | −111,025 |

| In-migrants | Out-migrants | Net migration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2011–12 | |||

| 2012–13 | |||

| 2013–14 | |||

| 2014–15 | |||

| 2015–16 | |||

| 2016–17 | |||

| 2017–18 | |||

| 2018–19 | |||

| 2019–20 | |||

| 2020–21 | |||

| 2021–22 | |||

| 2022–23 |

Source: Statistics Canada[2]

Saskatchewan

[edit]Inter-provincial migration has long been a demographic challenge for Saskatchewan, and it was often said that "Saskatchewan's most valuable export [was] its young people".[30] The trend reversed in 2006 as the nascent oil fracking industry started growing in the province, but returned to negative net migration starting in 2013. Most people migrating from Saskatchewan move west to Alberta or British Columbia.[31]

| In-migrants | Out-migrants | Net migration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2011–12 | |||

| 2012–13 | |||

| 2013–14 | |||

| 2014–15 | |||

| 2015–16 | |||

| 2016–17 | |||

| 2017–18 | |||

| 2018–19 | |||

| 2019–20 | |||

| 2020–21 | |||

| 2021–22 | |||

| 2022–23 |

Source: Statistics Canada[2]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Finnie, Ross (2004). "Who moves? A logit model analysis of inter-provincial migration in Canada". Applied Economics. 36 (16). School of Policy Studies at Queen’s University and Business and Labour Market Analysis Division, Statistics Canada: 1759–1779. doi:10.1080/0003684042000191147. S2CID 153591155.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Statistics Canada, table 051-0012: Interprovincial migrants, by age group and sex, Canada, provinces and territories, annual.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Interprovincial Migration in Canada: Quebeckers Vote with Their Feet" (PDF). www.fraserinstitute.org. Retrieved 2018-12-26.

- ^ Thornton, Patricia A. (Autumn 1985). "The Problem of Out-Migration from Atlantic Canada, 1871-1921: A New Look". Acadiensis. XV (1): 3–34. ISSN 0044-5851. JSTOR 30302704.

- ^ Bélanger, Damien-Claude (23 August 2000). "French Canadian Emigration to the United States, 1840–1930". Québec History, Claude Bélanger, Marianopolis College. Archived from the original on 25 January 2007. Retrieved 2007-01-31.

- ^ Bélanger, Claude. "Emigration to the United States from Canada and Quebec, 1840–1940". Quebec History. Marianopolis College. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- ^ Robert Craig Brown, and Ramsay Cook, Canada, 1896-1921: A nation transformed (1974) pp 253-62

- ^ Sprague, DN (1988). Canada and the Métis, 1869–1885. Waterloo, ON: Wilfrid Laurier University Press. pp. 33–67, 89–129. ISBN 0-88920-964-2.

- ^ Carr-Steward, Sheila (2001). "A Treaty Right to Education" (PDF). Canadian Journal of Education. 26 (2): 125–143. doi:10.2307/1602197. JSTOR 1602197. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04.

- ^ Lambrecht, Kirk N (1991). The Administration of Dominion Lands, 1870-1930.

- ^ a b "Dominion Lands Act | The Canadian Encyclopedia". www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca. Retrieved 2018-12-27.

- ^ The history of Saskatchewan's population Archived 2006-05-19 at the Wayback Machine from Statistics Canada

- ^ a b c Lew, Byron; Cater, Bruce (May 2011). "Interprovincial Migration in Canada, 1911–1951 and Beyond" (PDF). people.trentu.ca. Retrieved 2018-12-27.

- ^ Lionais, Doug; Murray, Christinas; Donatelli, Chloe (January 19, 2020). "Dependence on Interprovincial Migrant Labour in Atlantic Canadian Communities: The Role of the Alberta Economy". Societies. 10 (1): 11. doi:10.3390/soc10010011.

- ^ Ferguson, Nelson (January 1, 2011). "From Coal Pits to Tar Sands: Labour Migration Between an Atlantic Canadian Region and the Athabasca Oil Sands". Just Labour. 17 & 18 (Special Section). doi:10.25071/1705-1436.35. Retrieved 4 December 2022.

- ^ Smart, James (October 6, 2022). "Ducks by Kate Beaton review – powerful big oil memoir". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 December 2022.

- ^ Rogers, Shelagh (December 2, 2022). "Kate Beaton's affecting Ducks dives into the lonely life of labour in Alberta's oil sands". CBC. Retrieved 4 December 2022.

- ^ Amirault, David; de Munnik, Daniel; Miller, Sarah (Spring 2013). "Explaining Canada's regional Migration Patterns" (PDF). www.bankofcanada.ca. Bank of Canada Review. Retrieved 2018-12-28.

- ^ a b Wakefield, Jonny (2017-12-21). "Alberta no longer a loser on interprovincial migration". Edmonton Journal. Retrieved 2018-12-26.

- ^ a b "Interprovincial migration of French-speaking immigrants outside Quebec". aem. 2017-02-06. Retrieved 2018-12-27.

- ^ "The death of the Alberta dream - Macleans.ca". www.macleans.ca. Retrieved 2018-12-28.

- ^ "The Implications of New Brunswick's Population Forecasts" (PDF). www.nbjobs.ca. Retrieved 2018-12-27.

- ^ Bailey, Sue (19 April 2016). "Exodus? Newfoundland and Labrador's bleak finances fuel angst for the future". CBC News. The Canadian Press. Retrieved 2018-12-28.

- ^ Rashti, Amir Ahmadi; Koops, Adrian; Covey, Spencer (Spring 2015). "The Effects of Capital on Interprovincial Migration: A Nova Scotia Focused Assessment". Dalhousie Journal of Interdisciplinary Management. 11: 28.

- ^ White, Erik (4 May 2017). "Youth out migration a problem in northern Ontario towns, cities and First Nations". CBC News. Retrieved 18 December 2022.

- ^ Yarr, Kevin (August 16, 2016). "Immigration not keeping pace with people leaving P.E.I." CBC. Retrieved 2018-12-28.

- ^ Serebrin, Jacob (2018-07-26). "Quebec losing young people to interprovincial migration, report shows". Montreal Gazette Updated. Retrieved 2018-12-28.

- ^ "Net population gains or losses from interprovincial migration by language group, provinces and territories, 1991-1996 and 1996-2001". Archived from the original on 2008-06-17. Retrieved 2018-12-29.

- ^ "Interprovincial Migration by Mother Tongue for Interprovincial Migrants Aged 5 Years and Over, Provinces and Territories, 1971 to 2016". Statistics Canada. Retrieved 2010-03-11.

- ^ Elliot, Doug (2005). Interprovincial Migration - in the Encyclopedia of Saskatchewan. Regina: Canadian Plains Research Center, University of Regina. pp. 483–484.

- ^ "Exodus of Saskatchewan residents to Alberta, British Columbia, continues to plague province | Globalnews.ca". globalnews.ca. 2018-06-06. Archived from the original on 2018-12-29. Retrieved 2018-12-28.